Andrew Chatora's Blog

December 11, 2024

Charles Mungoshi – Eulogy to Greatness

You brought pure joy to the lecture rooms and classrooms. Always.

Big up Musimuvi, Shava.

When the history of Zimbabwean literature and arts is written, it would be a travesty and undoubtedly leave an indelible lacuna were Charles Mungoshi’s name to be omitted. Even so, I doubt much justice can be done in eulogising a literary giant whose influence transcend the literary scene in Zimbabwe, both in the pre and post-independence era. Sadly, today (17th of February 2019), I join my fellow citizens in mourning and celebrating the doyen that Mungoshi was to Zimbabwean literature, who sadly passed on in the early hours of Saturday morning, 16 February after bravely squaring up to a neurological illness for over a decade. My sincere condolences to his family, particularly his children and dearest wife, the iconic, affable, accomplished actress Jesesi Mungoshi.

This piece is about acknowledging and celebrating Mungoshi’s life, but in equal measure, – Jesesi’s role in standing by and supporting her husband also deserve plaudits. There is little doubt, the last few years were dark for our hero and scroll maestro, yet Jesesi kept the proverbial flame alive, – ensuring fellow Zimbabweans were kept abreast of Mungoshi’s fluctuating progress and in the end his fledgling literary career which still managed to leave us with another gem; Branching Streams Flow in the Dark (2013). Ironically, the night before his demise, the 15th of February, I had retweeted Jesesi’s promotional message in which she sought to raise finances for Mungoshi’s aforementioned latest offering.

But who was this man, Mungoshi, who educated Zimbabweans from diverse quarters of life, black or white through his books? I cannot even begin to quantify the immeasurable role he played to Zimbabwe’s high literacy rate and the literary field within and beyond ours borders. Born in December 1947 in the then Manyene Tribal Trust Lands in Chivhu, Charles, Lovemore, Muzuva, Mungoshi was a prolific, multi-award-winning novelist, poet, short-story writer, play wright, film scriptor, editor, translator and actor who was globally recognised and celebrated. Being contemporaries with other icons, i.e. Stanley Nyamufukudza, the late Chenjerai Hove and Dambudzo Marechera among others only testifies to how lofty the bar was for these luminaries as amply reflected within the depth and wide repertoire of their output. A grand storyteller, Mungoshi was a master of languages who wrote proficiently in both English and Shona, quite a feat yet to be replicated by contemporary Zimbabwean writers.

I first encountered Charles Mungoshi’s works in my formative years at primary school when I took part in a whole school drama production based on one of his earliest plays; Inongova Njake-Njake, loosely translated, Each Person Does His Own Thing (1980), itself an apt microcosmic wider metaphor on present day Zimbabwe’s woes. Inongova Njake-Njake was profound, poignant and a melancholic gritty drama, which in a dejavu way reverberated in some intimate personal experiences of my later life. Such was Mungoshi’s depth and genius, akin to yet another maestro, the late Samanyanga, Oliver Tuku Mtukudzi, – the sheer brilliance of the duo’s work was such that one always ended up locating their personal story within these sublime heroes’ cultural productions.

Jesesi Mungoshi (middle), a popular Zimbabwean actress who starred as Neria in the 1993 hit film Neria, at Oliver Mtukudzi’s funeral in Madziwa. Neria was written by award winning Zimbabwean writer Tsitsi Dangarembga. Photo: This is Africa/ A Chatora

Many a-times Mungoshi’s timeless classics would live to save the day for me as a befitting parting present for my English colleagues in many of the schools I taught in England, particularly Walking Still (1997), the collection of short stories. For me giving this Mungoshi text to colleagues was something special in a way, I always felt it was the chance to showcase and eulogise the rich Zimbabwean Literary talent and also an opportune moment to constantly remind colleagues of my Zimbabwean identity, jingoism and national pride especially for one working far away from home.

Growing up in the dusty streets of Dangamvura township, in Mutare, Mungoshi’s books were a recurrent hallmark on Zimbabwe’s school curriculum. Among other greats from the scroll maestro, I studied, Ndiko Kupindana Kwamazuwa (That’s How Time Passes) (1975) and Waiting for the Rain (1975) in my undergraduate degree at the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). I owe my English degree and vocation to this literary giant I seek to memorialize today. In subsequent years, in my life teaching A Level English to my prodigies’ in Mutasa district and Mutare in Manicaland province, the generality of my students could attest to my unbridled zeal for Mungoshi’s literature. Such were the depths of my admiration and adulation for the grandmaster of story, that the very first people to inform me of the legend’s passing on were among some of my erstwhile students, “sir, is it true, have you heard the news about Mungoshi.” Some emailed, some DMd via Twitter. Amidst our tears and emotional outpour of grief, one former student reminded me of a recurrent exam question, I used to assign them in relation to Mungoshi: ‘Nihilistic and pessimistic in outlook,’ How apt is this a description of Mungoshi’s works? Thus today, as I mourn the passing on of this herculean icon, I can’t help but chuckle at such reminisces I share with my erstwhile students.

I first met Mungoshi in 1993 my freshman year at UZ, it was a chance street encounter at Inez Terrace in Harare. As an old time, admirer reading English, the meeting couldn’t have been more opportune, a fact I made a point of bragging about to my fellow BA English classmates particularly Girly Masuku, who also happened to be Mungoshi’s neighbour in Chitungwiza and can attest to my endemic Mungoshi euphoria. I was pleasantly taken aback by your warmth in generating an off the cuff tittle-tattle with an absolute stranger as I. My only regret then is, there were no selfies at the time, as now I could be relishing my fifteen minutes of fame with Zimbabwe’s very own Charles Dickens or Wilkie Collins as posterity will live to remember you. We were later to meet at Harare International Book Fair in Harare Gardens, which was always a pivotal moment in celebrating literary talent similar to the way HIFA celebrates music talent.

Thank you, Mungoshi, for a life well lived in endowing and nurturing Zimbabwe’s creative world and for flying our flag high on the global stage. You were certainly one of the greats for publishing a whopping 18 books and bagging an array of the following accolades inter-alia; twice winning the Commonwealth Writers’ prize of Best book in Africa, having one of your poems curated by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as a permanent display of public art at their new headquarters in Seattle, Washington, US, IN 2011. Other awards include: The International PEN Award for publishing in 1981, NOMA Honourable Award for publishing in Africa, in the years, 1984, 1990 and 1992. The Setting Sun and The Rolling World was a New York Times notable book of the year in 1981. The University of Zimbabwe acknowledged Mungoshi’s immense input with an honorary doctorate degree in 2003, following his success in winning multiple awards which include Zimbabwe’s 75 best books where he appeared in the top five lists in both Shona and English categories. Apart from the University of Zimbabwe where he contributed immensely as Writer in Residence in the Department of English in 1985, Iowa University also awarded him a Fellowship in Writing for their International writing programme.

For a country with one of the highest literacy rates in Africa, Mungoshi deserve special recognition. To Mungoshi, famba zvakanaka mwana wevhu – go well son of the soil as we say in our tongue. We owe you a large debt of gratitude. Zimbabwe is poorer today, without you. Nonetheless we celebrate and take solace in your enduring voice. Your legacy will live on in our class rooms, lecture rooms, academic fora and beyond, inspiring posterity. As one user summed it in a tweet;

A reading nation would make Mungoshi a national hero…

But tiri vemagitare

RIP Great author.

A bit of context is essential here to enable a fuller deconstruction of the tweet above, the tweet is exposing the Tweep’s frustration with the State’s failure to accord national hero status to such a sublime luminary as Mungoshi, a similar accolade recently bestowed on the late Oliver Mtukudzi, another great as highlighted earlier.

As a befitting valediction, I have decided to laud Mungoshi’s indissoluble legacy by revisiting some of his larger than life characters, interacting and conversing with them in my inward psyche trajectory. Allusion has earlier been made to the vivacious Rindai. Mungoshi is a grand master at his unique insight into human nature and this skill is perfected with great finesse and astuteness throughout most of his works. Perhaps, none is this so evident as from an array of myriad conspicuously memorable characters from both Waiting for the Rain (1975) and Some Kinds of Wounds and Other Short Stories (1980). In Waiting for the Rain, there was a nomadic character, the enigmatic Garabha, who could come and go like the wind. He was exceptionally gifted when it came to playing the drum, thus he moved from village to village, plying his trade playing the drum, in exchange for alcohol. Garabha’s bohemianism meant he would never settle down. Alienated from his father Tongoona, Garabha was The Old Man’s favourite. Years later, teaching in English schools I immensely enjoyed bandying around the, play your own drum-not other people’s drum metaphor to my bemused students, to which if the metaphor was lost on them, I would hastily add with a chuckle, ‘don’t get involved, mind your own business.’ And who could ever forget, Waiting for the Rain’s protagonist, Lucifer of the infamous quote, ‘being born here was a biological and geographical error, I wish I was born elsewhere of other parents.’ Such was Mungoshi’s sublime craft, the alienation and identity crisis suffered by the then Africans in pre-independence Zimbabwe. Mungoshi’s nomenclature was also equally top notch as amply reflected in Uncle Kuruku, the ‘dodgy’ uncle in Waiting for the Rain. Interestingly, the name Kuruku, rhymes and is derived from the English word, ‘crook’, a liar and manipulator of note, which is very much in keeping with Uncle Kuruku’s traits in the text.

And then there was Betty, who was Garabha’s sister and could never seem to get married even though Matandangoma the medicine man or diviner was at hand to administer his potions. The beauty of Mungoshi’s craft is we all can identify with the wide repertoire of these infectious characters. One such character Big Blaz Sando from Some Kinds of Wounds and other Short Stories became a ubiquitous source of inside jokes between myself and my younger sibling, Arthur who over the years has consistently and valiantly reminded me, that my own personal foibles and eccentricities bore an uncanny resemblance to Mungoshi’s very own creation, Big Blaz Sando. In a nutshell, we have all seen, witnessed and interacted with, Garabha, Betty, Uncle Kuruku and Matandagoma the seer or medicine man in our mundane lives. These are not mere characters within books, but they are beings who have always been right there amongst us. This was the talent of Charles Mungoshi, – to produce, living breathing characters.

What better way to end than to quote the erudite Rino Zhuwarara my former UZ English don who characterises Mungoshi’s contribution well:

Mungoshi is a versatile and prolific Zimbabwean writer who has not only pioneered in the writing techniques of the Shona novel but has also made a lasting impact on the writing of short stories and novels in English. His overall contribution is bound to influence generations to come and as such his works deserve to be examined in detail.

The post Charles Mungoshi – Eulogy to Greatness appeared first on Andrew Chatora.

December 9, 2024

Andrew Chatora Awarded for Land-Themed Novel in New York

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora was silver recipient at the Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion held in New York on January 30. A noted crusader of African immigrant literature based in the UK, Chatora was recognized for his 2023 novel, “Harare Voices and Beyond”.

Chatora’s novel interrogates land reform discourse and race relations in Zimbabwe. Hollywood notables such as actors Matt Damon and Kevin Bacon were among this year’s Anthem recipients. Anthem laureates are recognized for their contribution in the arts, popular culture and community work. Now in their third edition, the awards honour “purpose and mission-driven work.”

In his acceptance speech, Chatora called on artists to keep on the prophetic watchpost: ‘‘Fellow creatives, together we can keep the momentum, relentlessly reflect the iniquities of our societies! Yes we can!’’

“In a year where so much is at stake, it is incredibly important to recognise impactful work and celebrate the progress happening globally,” Patricia McLoughlin, Anthem Awards General Manager remarked.

Chatora is the second Zimbabwean writer to receive the prize following US-based novelist and Mukana Press head honcho Munashe Kaseke’s 2023 award for her debut short story collection, Send Her Back and Other Short Stories.

“Zimbabwe’s history, long-run and more recent, has left behind a brutal legacy of racism, inequality and corruption. In Harare Voices and Beyond, I took on the ambitious challenge of telling a complex story about a complicated city, a devastated country and the multiple cultures that co-exist within,” Chatora said.

Steeped in Harare’s underbelly, Harare Voices and Beyond is not a narrative for the fainthearted. “Equally, the book also offers a minutiae examination on the place and scope of citizenship and nationhood in post-colonial Africa,” he added.

The novel deconstructs the simplistic dichotomy with which official discourse has sought to answer the question, “Who is a ‘real’ Zimbabwean?” “Do white people count? What about immigrants from other African countries?”

Segregated strands of Zimbabwean history meet where angels seldom tread, a quality associated with Chatora since his first novel, “Diaspora Dreams” took up the counterintuitive case of an African man teaching English in England.

Described by literary critic Tariro Ndoro as a “why-dunnit,” being a detective story that offers up a confession before it unravels, “Harare Voices and Beyond” also walks the reader through the contemporaneous problems of crime, corruption, drug abuse and mental health

“Many Zimbabwean writers before me have looked at the land question in their literary works. Harare Voices and Beyond afforded me the chance to contribute to a longstanding ongoing discourse,” Chatora reflected in the aftermath of his win.

“With my novel, Harare Voices and Beyond, I was attempting to fill in the missing link, the constant question on how it could have felt on the other side, the landed white community during the land reform.

The Where the Heart Is novelist takes exception to criticism from some decolonial aficionados who conclude that he has taken the side of the whites. “Nothing could be further from the truth. For me, it’s not so much about taking sides bringing nuance and unexpected twists to a polarized conversation,” explained Chatora.

It is a curious case of turning the tables on oneself for a novelist equally targeted for his pro-black crusades on the diaspora turf. Or, perhaps, a simple taste for complexity?

“So much had happened to white people during the land reform. Now, this should not be conflated with ‘I am anti-land reform’ as charged by some of my detractors.

“But, to reiterate, that is the essence of the writer. I will always defend my right to write without fear or favour on any contentious issues affecting our society,’’ he said.

Appropriately enough, Harare Voices and Beyond earned its first gong from a prize that recognizes artworks championing diversity and inclusion.

Author Biography

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. Chatora’s forthcoming novel, Born Here But Not in My Name , is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, Where the Heart Is , Harare Voices and Beyond and Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories, has cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded. Harare Voices and Beyond was awarded the 2024 Anthem Silver Award.

The post Andrew Chatora Awarded for Land-Themed Novel in New York appeared first on Andrew Chatora.

November 14, 2024

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora was silver recipient at the Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion held in New York on January 30. A noted crusader of African immigrant literature based in the UK, Chatora was recognized for his 2023 novel, “Harare Voices and Beyond”.

Chatora’s novel interrogates land reform discourse and race relations in Zimbabwe. Hollywood notables such as actors Matt Damon and Kevin Bacon were among this year’s Anthem recipients. Anthem laureates are recognized for their contribution in the arts, popular culture and community work. Now in their third edition, the awards honour “purpose and mission-driven work.”

In his acceptance speech, Chatora called on artists to keep on the prophetic watchpost: ‘‘Fellow creatives, together we can keep the momentum, relentlessly reflect the iniquities of our societies! Yes we can!’’

“In a year where so much is at stake, it is incredibly important to recognise impactful work and celebrate the progress happening globally,” Patricia McLoughlin, Anthem Awards General Manager remarked.

Chatora is the second Zimbabwean writer to receive the prize following US-based novelist and Mukana Press head honcho Munashe Kaseke’s 2023 award for her debut short story collection, Send Her Back and Other Short Stories.

“Zimbabwe’s history, long-run and more recent, has left behind a brutal legacy of racism, inequality and corruption. In Harare Voices and Beyond, I took on the ambitious challenge of telling a complex story about a complicated city, a devastated country and the multiple cultures that co-exist within,” Chatora said.

Steeped in Harare’s underbelly, Harare Voices and Beyond is not a narrative for the fainthearted. “Equally, the book also offers a minutiae examination on the place and scope of citizenship and nationhood in post-colonial Africa,” he added.

The novel deconstructs the simplistic dichotomy with which official discourse has sought to answer the question, “Who is a ‘real’ Zimbabwean?” “Do white people count? What about immigrants from other African countries?”

Segregated strands of Zimbabwean history meet where angels seldom tread, a quality associated with Chatora since his first novel, “Diaspora Dreams” took up the counterintuitive case of an African man teaching English in England.

Described by literary critic Tariro Ndoro as a “why-dunnit,” being a detective story that offers up a confession before it unravels, “Harare Voices and Beyond” also walks the reader through the contemporaneous problems of crime, corruption, drug abuse and mental health

“Many Zimbabwean writers before me have looked at the land question in their literary works. Harare Voices and Beyond afforded me the chance to contribute to a longstanding ongoing discourse,” Chatora reflected in the aftermath of his win.

“With my novel, Harare Voices and Beyond, I was attempting to fill in the missing link, the constant question on how it could have felt on the other side, the landed white community during the land reform.

The Where the Heart Is novelist takes exception to criticism from some decolonial aficionados who conclude that he has taken the side of the whites. “Nothing could be further from the truth. For me, it’s not so much about taking sides bringing nuance and unexpected twists to a polarized conversation,” explained Chatora.

It is a curious case of turning the tables on oneself for a novelist equally targeted for his pro-black crusades on the diaspora turf. Or, perhaps, a simple taste for complexity?

“So much had happened to white people during the land reform. Now, this should not be conflated with ‘I am anti-land reform’ as charged by some of my detractors.

“But, to reiterate, that is the essence of the writer. I will always defend my right to write without fear or favour on any contentious issues affecting our society,’’ he said.

Appropriately enough, Harare Voices and Beyond earned its first gong from a prize that recognizes artworks championing diversity and inclusion.

Author Biography

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. Chatora’s forthcoming novel, Born Here But Not in My Name , is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, Where the Heart Is , Harare Voices and Beyond and Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories, has cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded. Harare Voices and Beyond was awarded the 2024 Anthem Silver Award.

The post Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York appeared first on Andrew Chatora.

October 31, 2024

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora was silver recipient at the Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion held in New York on January 30. A noted crusader of African immigrant literature based in the UK, Chatora was recognized for his 2023 novel, “Harare Voices and Beyond”.

Chatora’s novel interrogates land reform discourse and race relations in Zimbabwe. Hollywood notables such as actors Matt Damon and Kevin Bacon were among this year’s Anthem recipients. Anthem laureates are recognized for their contribution in the arts, popular culture and community work. Now in their third edition, the awards honour “purpose and mission-driven work.”

In his acceptance speech, Chatora called on artists to keep on the prophetic watchpost: ‘‘Fellow creatives, together we can keep the momentum, relentlessly reflect the iniquities of our societies! Yes we can!’’

“In a year where so much is at stake, it is incredibly important to recognise impactful work and celebrate the progress happening globally,” Patricia McLoughlin, Anthem Awards General Manager remarked.

Chatora is the second Zimbabwean writer to receive the prize following US-based novelist and Mukana Press head honcho Munashe Kaseke’s 2023 award for her debut short story collection, Send Her Back and Other Short Stories.

“Zimbabwe’s history, long-run and more recent, has left behind a brutal legacy of racism, inequality and corruption. In Harare Voices and Beyond, I took on the ambitious challenge of telling a complex story about a complicated city, a devastated country and the multiple cultures that co-exist within,” Chatora said.

Steeped in Harare’s underbelly, Harare Voices and Beyond is not a narrative for the fainthearted. “Equally, the book also offers a minutiae examination on the place and scope of citizenship and nationhood in post-colonial Africa,” he added.

The novel deconstructs the simplistic dichotomy with which official discourse has sought to answer the question, “Who is a ‘real’ Zimbabwean?” “Do white people count? What about immigrants from other African countries?”

Segregated strands of Zimbabwean history meet where angels seldom tread, a quality associated with Chatora since his first novel, “Diaspora Dreams” took up the counterintuitive case of an African man teaching English in England.

Described by literary critic Tariro Ndoro as a “why-dunnit,” being a detective story that offers up a confession before it unravels, “Harare Voices and Beyond” also walks the reader through the contemporaneous problems of crime, corruption, drug abuse and mental health

“Many Zimbabwean writers before me have looked at the land question in their literary works. Harare Voices and Beyond afforded me the chance to contribute to a longstanding ongoing discourse,” Chatora reflected in the aftermath of his win.

“With my novel, Harare Voices and Beyond, I was attempting to fill in the missing link, the constant question on how it could have felt on the other side, the landed white community during the land reform.

The Where the Heart Is novelist takes exception to criticism from some decolonial aficionados who conclude that he has taken the side of the whites. “Nothing could be further from the truth. For me, it’s not so much about taking sides bringing nuance and unexpected twists to a polarized conversation,” explained Chatora.

It is a curious case of turning the tables on oneself for a novelist equally targeted for his pro-black crusades on the diaspora turf. Or, perhaps, a simple taste for complexity?

“So much had happened to white people during the land reform. Now, this should not be conflated with ‘I am anti-land reform’ as charged by some of my detractors.

“But, to reiterate, that is the essence of the writer. I will always defend my right to write without fear or favour on any contentious issues affecting our society,’’ he said.

Appropriately enough, Harare Voices and Beyond earned its first gong from a prize that recognizes artworks championing diversity and inclusion.

Author Biography

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. Chatora’s forthcoming novel, Born Here But Not in My Name , is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, Where the Heart Is , Harare Voices and Beyond and Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories, has cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded. Harare Voices and Beyond was awarded the 2024 Anthem Silver Award.

The post Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York first appeared on Andrew Chatora.

The post Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York appeared first on Andrew Chatora.

August 23, 2024

ZTN Morning Rush Reviews Andrew Chatora’s Latest Book

The post ZTN Morning Rush Reviews Andrew Chatora’s Latest Book appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

February 19, 2024

Charles Lovemore Mungoshi – Eulogy to Greatness

You brought pure joy to the lecture rooms and classrooms. Always.

Big up Musimuvi, Shava.

When the history of Zimbabwean literature and arts is written, it would be a travesty and undoubtedly leave an indelible lacuna were Charles Mungoshi’s name to be omitted. Even so, I doubt much justice can be done in eulogising a literary giant whose influence transcend the literary scene in Zimbabwe, both in the pre and post-independence era. Sadly, today (17th of February 2019), I join my fellow citizens in mourning and celebrating the doyen that Mungoshi was to Zimbabwean literature, who sadly passed on in the early hours of Saturday morning, 16 February after bravely squaring up to a neurological illness for over a decade. My sincere condolences to his family, particularly his children and dearest wife, the iconic, affable, accomplished actress Jesesi Mungoshi.

This piece is about acknowledging and celebrating Mungoshi’s life, but in equal measure, – Jesesi’s role in standing by and supporting her husband also deserve plaudits. There is little doubt, the last few years were dark for our hero and scroll maestro, yet Jesesi kept the proverbial flame alive, – ensuring fellow Zimbabweans were kept abreast of Mungoshi’s fluctuating progress and in the end his fledgling literary career which still managed to leave us with another gem; Branching Streams Flow in the Dark (2013). Ironically, the night before his demise, the 15th of February, I had retweeted Jesesi’s promotional message in which she sought to raise finances for Mungoshi’s aforementioned latest offering.

But who was this man, Mungoshi, who educated Zimbabweans from diverse quarters of life, black or white through his books? I cannot even begin to quantify the immeasurable role he played to Zimbabwe’s high literacy rate and the literary field within and beyond ours borders. Born in December 1947 in the then Manyene Tribal Trust Lands in Chivhu, Charles, Lovemore, Muzuva, Mungoshi was a prolific, multi-award-winning novelist, poet, short-story writer, play wright, film scriptor, editor, translator and actor who was globally recognised and celebrated. Being contemporaries with other icons, i.e. Stanley Nyamufukudza, the late Chenjerai Hove and Dambudzo Marechera among others only testifies to how lofty the bar was for these luminaries as amply reflected within the depth and wide repertoire of their output. A grand storyteller, Mungoshi was a master of languages who wrote proficiently in both English and Shona, quite a feat yet to be replicated by contemporary Zimbabwean writers.

I first encountered Charles Mungoshi’s works in my formative years at primary school when I took part in a whole school drama production based on one of his earliest plays; Inongova Njake-Njake, loosely translated, Each Person Does His Own Thing (1980), itself an apt microcosmic wider metaphor on present day Zimbabwe’s woes. Inongova Njake-Njake was profound, poignant and a melancholic gritty drama, which in a dejavu way reverberated in some intimate personal experiences of my later life. Such was Mungoshi’s depth and genius, akin to yet another maestro, the late Samanyanga, Oliver Tuku Mtukudzi, – the sheer brilliance of the duo’s work was such that one always ended up locating their personal story within these sublime heroes’ cultural productions.

Jesesi Mungoshi (middle), a popular Zimbabwean actress who starred as Neria in the 1993 hit film Neria, at Oliver Mtukudzi’s funeral in Madziwa. Neria was written by award winning Zimbabwean writer Tsitsi Dangarembga. Photo: This is Africa/ A Chatora

Many a-times Mungoshi’s timeless classics would live to save the day for me as a befitting parting present for my English colleagues in many of the schools I taught in England, particularly Walking Still (1997), the collection of short stories. For me giving this Mungoshi text to colleagues was something special in a way, I always felt it was the chance to showcase and eulogise the rich Zimbabwean Literary talent and also an opportune moment to constantly remind colleagues of my Zimbabwean identity, jingoism and national pride especially for one working far away from home.

Growing up in the dusty streets of Dangamvura township, in Mutare, Mungoshi’s books were a recurrent hallmark on Zimbabwe’s school curriculum. Among other greats from the scroll maestro, I studied, Ndiko Kupindana Kwamazuwa (That’s How Time Passes) (1975) and Waiting for the Rain (1975) in my undergraduate degree at the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). I owe my English degree and vocation to this literary giant I seek to memorialize today. In subsequent years, in my life teaching A Level English to my prodigies’ in Mutasa district and Mutare in Manicaland province, the generality of my students could attest to my unbridled zeal for Mungoshi’s literature. Such were the depths of my admiration and adulation for the grandmaster of story, that the very first people to inform me of the legend’s passing on were among some of my erstwhile students, “sir, is it true, have you heard the news about Mungoshi.” Some emailed, some DMd via Twitter. Amidst our tears and emotional outpour of grief, one former student reminded me of a recurrent exam question, I used to assign them in relation to Mungoshi: ‘Nihilistic and pessimistic in outlook,’ How apt is this a description of Mungoshi’s works? Thus today, as I mourn the passing on of this herculean icon, I can’t help but chuckle at such reminisces I share with my erstwhile students.

I first met Mungoshi in 1993 my freshman year at UZ, it was a chance street encounter at Inez Terrace in Harare. As an old time, admirer reading English, the meeting couldn’t have been more opportune, a fact I made a point of bragging about to my fellow BA English classmates particularly Girly Masuku, who also happened to be Mungoshi’s neighbour in Chitungwiza and can attest to my endemic Mungoshi euphoria. I was pleasantly taken aback by your warmth in generating an off the cuff tittle-tattle with an absolute stranger as I. My only regret then is, there were no selfies at the time, as now I could be relishing my fifteen minutes of fame with Zimbabwe’s very own Charles Dickens or Wilkie Collins as posterity will live to remember you. We were later to meet at Harare International Book Fair in Harare Gardens, which was always a pivotal moment in celebrating literary talent similar to the way HIFA celebrates music talent.

Thank you, Mungoshi, for a life well lived in endowing and nurturing Zimbabwe’s creative world and for flying our flag high on the global stage. You were certainly one of the greats for publishing a whopping 18 books and bagging an array of the following accolades inter-alia; twice winning the Commonwealth Writers’ prize of Best book in Africa, having one of your poems curated by The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as a permanent display of public art at their new headquarters in Seattle, Washington, US, IN 2011. Other awards include: The International PEN Award for publishing in 1981, NOMA Honourable Award for publishing in Africa, in the years, 1984, 1990 and 1992. The Setting Sun and The Rolling World was a New York Times notable book of the year in 1981. The University of Zimbabwe acknowledged Mungoshi’s immense input with an honorary doctorate degree in 2003, following his success in winning multiple awards which include Zimbabwe’s 75 best books where he appeared in the top five lists in both Shona and English categories. Apart from the University of Zimbabwe where he contributed immensely as Writer in Residence in the Department of English in 1985, Iowa University also awarded him a Fellowship in Writing for their International writing programme.

For a country with one of the highest literacy rates in Africa, Mungoshi deserve special recognition. To Mungoshi, famba zvakanaka mwana wevhu – go well son of the soil as we say in our tongue. We owe you a large debt of gratitude. Zimbabwe is poorer today, without you. Nonetheless we celebrate and take solace in your enduring voice. Your legacy will live on in our class rooms, lecture rooms, academic fora and beyond, inspiring posterity. As one user summed it in a tweet;

A reading nation would make Mungoshi a national hero…

But tiri vemagitare

RIP Great author.

A bit of context is essential here to enable a fuller deconstruction of the tweet above, the tweet is exposing the Tweep’s frustration with the State’s failure to accord national hero status to such a sublime luminary as Mungoshi, a similar accolade recently bestowed on the late Oliver Mtukudzi, another great as highlighted earlier.

As a befitting valediction, I have decided to laud Mungoshi’s indissoluble legacy by revisiting some of his larger than life characters, interacting and conversing with them in my inward psyche trajectory. Allusion has earlier been made to the vivacious Rindai. Mungoshi is a grand master at his unique insight into human nature and this skill is perfected with great finesse and astuteness throughout most of his works. Perhaps, none is this so evident as from an array of myriad conspicuously memorable characters from both Waiting for the Rain (1975) and Some Kinds of Wounds and Other Short Stories (1980). In Waiting for the Rain, there was a nomadic character, the enigmatic Garabha, who could come and go like the wind. He was exceptionally gifted when it came to playing the drum, thus he moved from village to village, plying his trade playing the drum, in exchange for alcohol. Garabha’s bohemianism meant he would never settle down. Alienated from his father Tongoona, Garabha was The Old Man’s favourite. Years later, teaching in English schools I immensely enjoyed bandying around the, play your own drum-not other people’s drum metaphor to my bemused students, to which if the metaphor was lost on them, I would hastily add with a chuckle, ‘don’t get involved, mind your own business.’ And who could ever forget, Waiting for the Rain’s protagonist, Lucifer of the infamous quote, ‘being born here was a biological and geographical error, I wish I was born elsewhere of other parents.’ Such was Mungoshi’s sublime craft, the alienation and identity crisis suffered by the then Africans in pre-independence Zimbabwe. Mungoshi’s nomenclature was also equally top notch as amply reflected in Uncle Kuruku, the ‘dodgy’ uncle in Waiting for the Rain. Interestingly, the name Kuruku, rhymes and is derived from the English word, ‘crook’, a liar and manipulator of note, which is very much in keeping with Uncle Kuruku’s traits in the text.

And then there was Betty, who was Garabha’s sister and could never seem to get married even though Matandangoma the medicine man or diviner was at hand to administer his potions. The beauty of Mungoshi’s craft is we all can identify with the wide repertoire of these infectious characters. One such character Big Blaz Sando from Some Kinds of Wounds and other Short Stories became a ubiquitous source of inside jokes between myself and my younger sibling, Arthur who over the years has consistently and valiantly reminded me, that my own personal foibles and eccentricities bore an uncanny resemblance to Mungoshi’s very own creation, Big Blaz Sando. In a nutshell, we have all seen, witnessed and interacted with, Garabha, Betty, Uncle Kuruku and Matandagoma the seer or medicine man in our mundane lives. These are not mere characters within books, but they are beings who have always been right there amongst us. This was the talent of Charles Mungoshi, – to produce, living breathing characters.

What better way to end than to quote the erudite Rino Zhuwarara my former UZ English don who characterises Mungoshi’s contribution well:

Mungoshi is a versatile and prolific Zimbabwean writer who has not only pioneered in the writing techniques of the Shona novel but has also made a lasting impact on the writing of short stories and novels in English. His overall contribution is bound to influence generations to come and as such his works deserve to be examined in detail.

The post Charles Lovemore Mungoshi – Eulogy to Greatness appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

February 5, 2024

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York

Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora was silver recipient at the Anthem Award for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion held in New York on January 30. A noted crusader of African immigrant literature based in the UK, Chatora was recognized for his 2023 novel, “Harare Voices and Beyond”.

Chatora’s novel interrogates land reform discourse and race relations in Zimbabwe. Hollywood notables such as actors Matt Damon and Kevin Bacon were among this year’s Anthem recipients. Anthem laureates are recognized for their contribution in the arts, popular culture and community work. Now in their third edition, the awards honour “purpose and mission-driven work.”

In his acceptance speech, Chatora called on artists to keep on the prophetic watchpost: ‘‘Fellow creatives, together we can keep the momentum, relentlessly reflect the iniquities of our societies! Yes we can!’’

“In a year where so much is at stake, it is incredibly important to recognise impactful work and celebrate the progress happening globally,” Patricia McLoughlin, Anthem Awards General Manager remarked.

Chatora is the second Zimbabwean writer to receive the prize following US-based novelist and Mukana Press head honcho Munashe Kaseke’s 2023 award for her debut short story collection, Send Her Back and Other Short Stories.

“Zimbabwe’s history, long-run and more recent, has left behind a brutal legacy of racism, inequality and corruption. In Harare Voices and Beyond, I took on the ambitious challenge of telling a complex story about a complicated city, a devastated country and the multiple cultures that co-exist within,” Chatora said.

Steeped in Harare’s underbelly, Harare Voices and Beyond is not a narrative for the fainthearted. “Equally, the book also offers a minutiae examination on the place and scope of citizenship and nationhood in post-colonial Africa,” he added.

The novel deconstructs the simplistic dichotomy with which official discourse has sought to answer the question, “Who is a ‘real’ Zimbabwean?” “Do white people count? What about immigrants from other African countries?”

Segregated strands of Zimbabwean history meet where angels seldom tread, a quality associated with Chatora since his first novel, “Diaspora Dreams” took up the counterintuitive case of an African man teaching English in England.

Described by literary critic Tariro Ndoro as a “why-dunnit,” being a detective story that offers up a confession before it unravels, “Harare Voices and Beyond” also walks the reader through the contemporaneous problems of crime, corruption, drug abuse and mental health

“Many Zimbabwean writers before me have looked at the land question in their literary works. Harare Voices and Beyond afforded me the chance to contribute to a longstanding ongoing discourse,” Chatora reflected in the aftermath of his win.

“With my novel, Harare Voices and Beyond, I was attempting to fill in the missing link, the constant question on how it could have felt on the other side, the landed white community during the land reform.

The Where the Heart Is novelist takes exception to criticism from some decolonial aficionados who conclude that he has taken the side of the whites. “Nothing could be further from the truth. For me, it’s not so much about taking sides bringing nuance and unexpected twists to a polarized conversation,” explained Chatora.

It is a curious case of turning the tables on oneself for a novelist equally targeted for his pro-black crusades on the diaspora turf. Or, perhaps, a simple taste for complexity?

“So much had happened to white people during the land reform. Now, this should not be conflated with ‘I am anti-land reform’ as charged by some of my detractors.

“But, to reiterate, that is the essence of the writer. I will always defend my right to write without fear or favour on any contentious issues affecting our society,’’ he said.

Appropriately enough, Harare Voices and Beyond earned its first gong from a prize that recognizes artworks championing diversity and inclusion.

Author Biography

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. Chatora’s forthcoming novel, Born Here But Not in My Name , is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit. His debut novella, Diaspora Dreams (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, Where the Heart Is , Harare Voices and Beyond and Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories, has cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded. Harare Voices and Beyond was awarded the 2024 Anthem Silver Award.

The post Zimbabwean writer Andrew Chatora awarded for land-themed novel in New York appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

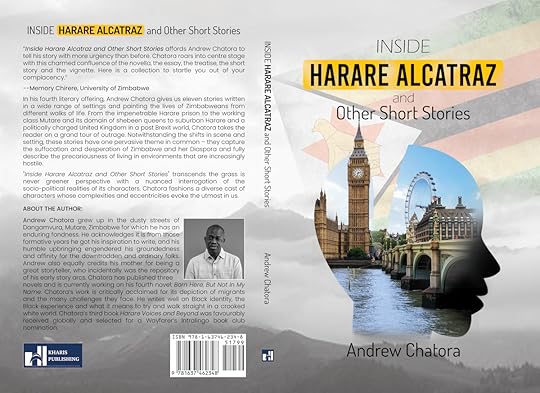

Navigating Zimbabwe and her Diaspora: Through the Years Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories

Zimbabwe’s socio-political landscape and the acutely complex circumstances of the Zimbabwe diaspora informs the eleven stories that form Andrew Chatora’s fourth book and debut short story collection, Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories. Told from the viewpoints of several narrators living in diverse locales, Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories touches on the themes of turmoil, tenacity, broken society and sometimes sheer desperation.

When it reaches the bookshops in your neighbourhood this February 2024 you may see that Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories offers a fine assembly of different tones, voices, and settings, giving a view of a Zimbabwe and her Diaspora that is multifaceted writes Tariro Ndoro.

The collection opens with the scene of a man being thrown “kicking and screaming” into a Harare jail cell in the title story, “Inside Harare Alcatraz” which takes place in Harare’s maximum-security prison. The prison is nicknamed ‘Alcatraz’ after the now defunct impenetrable and infamous Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary Prison off the coast of San Francisco. In this story, Chatora weaves the tale of an unnamed man who is assigned to go to this prison and pretend to be a prisoner in the same cell as two “infamous” political prisoners, highlighting the harsh and politically abused environs of Zimbabwe’s correctional services. In this story, Chipendani the protagonist must make difficult and surprising choices that will change the shape of his life forever.

However, the bulk of the book is set in Dangamvura, a township in Mutare, Zimbabwe’s third largest city. Although Chatora has affectionately mentioned both Dangamvura and the greater Mutare in his first two books, it is in Inside Harare Alcatraz that he fully pays homage to his hometown.

“Estelle the Shebeen Queen and Other Dangamvura Vignettes,” for instance, is the story of a Dangamvura shebeen queen who runs a not so covert brothel in which she employs her own daughters:

I was privileged enough to be neighbours with Estelle and only lived two doors away from her. Estelle was an unmarried woman in her late fifties with a brood of daughters, who mostly were single mothers crowding at her famed 4 roomed house; kwaMagumete as it was called; though it beats me how they were able to live comfortably under such squalid conditions of overcrowding, constantly stepping on each other’s toes. The irony growing up in my hood, Estelle’s house was termed four roomed house but in reality, they were two bedroomed houses itself an indictment of the colonial regime which never seem to take into account the big number of African families and how they could benefit from corresponding adequate housing.

Chatora fully describes the underbelly of township life as he details Estelle’s and her daughters’ methods of ensnaring hapless patrons and then mortgaging their debts to the hilt. These women are villains but, like in Yasher Kemal’s Memed My Hawk, the villain can as well be a plausible hero. Estelle and her daughters must be hitting back at society that has always disposed women.

In one other story in this book, one family, the Chatikobos, barely survives. Later on, Chatora delineates the foibles of the newly rich black middle class in “Of Sekuru Kongiri and Us” as one man sacrifices his cultural upbringing at the altar of upward mobility. His wife is a louder expression of what Kongiri is able to hide about himself. After the sinister matter-of fact tone displayed in “Estelle the Shebeen Queen,” “ Of Sekuru Kongiri and Us,” one has already experienced a more playful side of both Dangamvura and the author.

Chatora then uses the template of court hearings and legal procedure to illustrate gender politics and the violence that often surrounds sex. Two such stories are “A Snap Decision” and “Tales of Survival: Avenues and Epworth.” The former takes place in the United Kingdom, in which a woman; Pamhidzai has been accused of killing her mother’s lover. The story is, in many ways, reminiscent of Jag Mundhra’s 2006 film, Provoked, which tells the story of a young Indian woman who migrates to the United Kingdom for an arranged marriage and yet she only face years of abuse at the hands of her husband. Seeing no other way out for herself, she snaps and burns him alive. Chatora has a knack for steeping his stories in legal complications. You may want to coin a term legal-literature around Chatora’s works.

In “A Snap Decision,” the protagonist, Pamhidzai, endures abuse at the hands of a revolving door of men who date her mother. In the end, she stabs the last one to death. Pamhidzai’s story also highlights the effect of emigration on African families, a theme Chatora often visits in his other books:

It was moments like these when I felt myself spiralling into a dark pit of despair, I was unable to extricate myself from or to claw myself out of. Why did I have to belong to such a dysfunctional family as ours? I hated mummy more and blamed her for driving dad away in the first place.

“Tales of Survival: Avenues and Epworth,” on the other hand, describes the life stories of several sex workers living in one of Harare’s diciest ghettoes – Epworth. Herein Chatora highlights the social and economic ills that force young women to take to sex work when they are robbed of other choices. But the most important thing is that several key people try to put a stop to all this. Whether this is achieved or not, is for the reader to decide.

Andrew Chatora’s Short stories remind me of what Elizabeth Bowen’s words that the short story, more than the novel, is able to place man alone on that “stage which, inwardly, every man is conscious of occupying alone.”

Chatora’s other books, Diaspora Dreams, Where the Heart Is, and Harare Voices and Beyond are set in Thames Valley, England with several scenes set in Zimbabwe. The three books have the story of one family told in long form fiction over a long period of time. Not so with Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories. In this instalment, Chatora uses more characters to inhabit more locales and the greater part of the book is set in his native Zimbabwe. From the jail cells of Chikurubi to the leafy suburbs of Harare, Chatora methodically reveals the desperate lives of the base.

Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories is available through https://kharispublishing.com and major online retail sites such as Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Christianbooks.com, Walmart, etc., or by contacting the author at: ajchatora@gmail.com Order your copy today!

Reviewer Biography

Tariro Ndoro is a Zimbabwean poet and storyteller. Born in Harare but raised in a smattering of small towns, Tariro holds a BSc in Microbiology and an MA in Creative Writing.

Her work has been published in numerous international journals and anthologies including 20.35 Africa: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry (Brittle Paper, 2018), Kotaz, New Contrast, Oxford Poetry, and Puerto del Sol. Her poetry has been shortlisted for the 2018 Babishai Niwe Poetry Prize and awarded second place for the 2017 DALRO Prize. Agringada is her debut collection

The post Navigating Zimbabwe and her Diaspora: Through the Years Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

Chatora Opens Window to Colony, Empire Experiences in New Book

I am privileged to reveal that this February, 2024, Andrew Chatora, the United Kingdom-based Zimbabwean novelist, is set to release his debut short story collection called “Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Short Stories”.

The author of “Diaspora Dreams” has temporarily quit the novel to give us this charmed confluence of the novella, the short story, the vignette, and the poetic essay.

A collection of shorter forms usually allows the artist to tell his story in titbits, and with more varied urgency than what a novel allows.

This book of eleven pieces, is made up of briefly fleeting and powerful scenes. In his best moments, Chatora shows us the kaleidoscopic experiences of what it means growing up in Zimbabwe’s Dangamvura, Mutare, which breathes like Leopold Senghor’s Harlem.

One should not miss the exciting series of short pieces under the title “Estelle, the Shebeen Queen and other Dangamvura vignettes”, because Estelle rules here. She arranges and re-arranges everyone in Dangamvura, without having to leave her seat! She can toss over the so-called man’s world the way a gambler tosses a coin.

Upside down. Inside out.

Much early in the story, we are told that; “Estelle was a woman in her late fifties with a brood of daughters, mostly single mothers, who crowded her infamous four-roomed house — kwaMagumete as it was affectionately called.”

It is early days into Zimbabwe’s Independence, and most mavericks necessarily have to belong to the ended war, the party, the suburb, the market, the shebeen, and to Estelle!

Dangamvura Township is a catalogue of characters. There is, for example, the police officer, Wabenzi, who deliberately encourages gruesome tales about himself to float around, trying to cultivate a legendary folklore status in order to cow the community into submission. He is a cult hero in a city in a nation that is emerging from a gruesome war of liberation.

Then there is a respectable churchman, Baba Makuwaza, who is dragged from Estelle’s shebeen half-naked, with his torn boxers on display, as Estelle hurls invectives at both hapless Makuwaza and his wife.

Do not miss the other story, “Tales of Survival”, which is set in Epworth, on the outskirts of Harare. Each woman’s narrative in that series carries the day with pathos, contradictions and humour. That way, the vignettes bring to life the plight of low-class Harare women, and how they gradually find ways of grabbing at least little victories from their miseries.

They are struggling to struggle! And they struggle on.

“Of Sekuru Kongiri and Us” is a touching story. For me, it could be the best story in this whole collection. It is potentially a prize-winning short story! It takes the reader through various emotions.

The most delicate part of the story goes: “It’s important that I make it clear he was not always Sekuru Kongiri. First, he was Uncle Alfred . . . the once generous man increasingly became so tight-fisted and miserly with money, only to his side of the family of course, that Dr. Watson nicknamed him, ‘as tight fisted as concrete . . .’ and so Sekuru Kongiri became up to this day.”

The story has a unique pace and amazing African cultural depth, too. This tragic-comic story will not fail those interested in the vicissitudes of African culture.

The other story to look out for is “Smoke and Mirrors”. It is set in the UK. At Wendover Heights care home where Zimbabwean man, Onai, works, looking after vulnerable adults, he meets Iffy, a Nigerian woman, and as workmates from Africa, they bond easily.

But, one day, Iffy brings an exciting business plan to Onai: “I know about your wife and family, I’m not an idiot. It’s not a real marriage I’m talking of here, Onai. You have dual Zimbabwean-British citizenship, don’t you? Right.

“So that’s perfect for us; we would pay you whatever amount you want to falsely get married to someone from any of the African countries we deal with. It will be a sham marriage. The idea is to get them into the country, allow them to settle into their own life; they get a job, acclimatize to their mundane lives here, after which you file for divorce.

“Or sometimes, it may be someone already in the country, and they don’t have legal status. Dead easy, Onai; all parties win. She gets her papers; you get your money. It’s a win-win for everyone. Easy peasy.’’

In the end, one of them gets into agony because of all this! This story stinks! You may need a towel as you read it.

“Fari’s Last Smile” is a story that reads like something from the pages of Thomas Hardy’s “The Distracted Preacher and other Tales”. A man keeps on falling, but rising each time that he falls, in order to fall again.

But each time that he falls, he does it in a more novel way than before. He is even conned by people back home in Zimbabwe. They tell him that they are using the money he is sending them to build a house. The story teaches through tears.

In the title story itself, which is an intriguing mixture of fact and fiction, there are the heart-rending experiences of political prisoners, ironically in independent and contemporary Zimbabwe.

You stagger as you watch how those with power in Africa scuttle the chessboard, forcing us to doubt African beauty, African pride and African wisdom. But the so-called terrible man actually confesses in that story. He is the story. He is the only hope we have. You want to kiss that story in the end. A terrible beauty is born.

But Andrew Chatora is relentless. He crosses the English Channel and marches into the African Diaspora community of England, and gives us a snap survey of racism, which sits at the very core of contemporary England’s psyche.

In one of the stories, which is actually an essay short story, the child narrator, Anesu, bemoans the exigency of systemic and institutionalised racism. He is a first-generation Zimbabwean-British immigrant, who confronts a system his parents submissively put up with.

Sometimes you want to puke because the land which purports to be the quintessence of democracy is itself rotten at the very core, and is full of “white savages”!

In the story “A Snap Decision”, a girl, Pamhidzai, has to contend with the question: “Why did you stab your mother’s lover?”

What follows is a mixture of the past and present, and Chatora is back to his quintessential theme of the struggles between men and women in marriage, especially at the instigation of a foreign environment.

Then, there is a story in which you are sitting with your daughter in England and the fool innocently asks you, from nowhere: “Why don’t you use Shona names, since you are from Zimbabwe, and you are always banging on about preserving one’s cultural heritage and identity?”

Then, in explaining to her who you are, you take one winding road that unravels Britain’s long, but pitiful relationship with the migrant. For this story, dear reader, you will have to put on your spectacles!

I say that because here is a subliminal, meandering, but enlightening treatise on race, class, gender and identity politics in the Diaspora. You are caught up in the rough and tumble of Britain’s diverse cityscapes, names, ethnicity and place of abode. One has to deploy them tactfully in the politics of survival.

There is a somewhat sombre tone in “First Wave”, a story where a Zimbabwean nurse, Shumirai, working in the British national health service, takes a poignant tour de force of how she and her fellow colleagues fought and conquered a global pandemic which wreaked havoc on lives in its early days.

In equal measure, in a moving tribute, Shumirai mourns and lauds the passing of her work colleagues, patients and family as she grapples with the government’s mishandling of the crisis. Chatora charts new territory by offering dual perspectives from different black narrators’ lived experiences in both the former colony, Zimbabwe, and its colonial master, Britain, in a new normal shift, that is, post-independence reverse migration cycle of citizens to the former colony.

Originally appeared in The Herald

Andrew Chatora is a noted exponent of the African Diaspora novel. Candid, relentlessly engaging and vulnerable, his novels are a polarising affair among social critics and literary aficionados. His forthcoming novel, “Born Here, But Not in My Name”, is a long-run treatment of race relations in Britain, featuring the English classroom as a microcosm of wider society post-Brexit.

His debut novella, “Diaspora Dreams” (2021), was the well-received nominee of the National Arts Merit Awards in Zimbabwe, while his subsequent works, “Where the Heart Is”, “Harare Voices and Beyond” and “Inside Harare Alcatraz and Other Stories”, have cemented his contribution as a voice of the excluded. “Harare Voices and Beyond” recently won the 2024 silver category of the Anthem Awards in New York.

The post Chatora Opens Window to Colony, Empire Experiences in New Book appeared first on Andrew Chatora .

July 24, 2023

Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror: Fluid identities – life beyond virtual reality

Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror is a work of art worthy of academic study. This multi-layered, Twilight Zone-esque anthology television series taps into our collective unease, technological anxieties and paranoia, presenting the viewer with a variety of potential futures. As episode 1 of Season 5, “Striking Vipers’ is the latest offering – and it does not disappoint. A range of pertinent, intersecting subjects are introduced, including the bonds of friendship, virtual sex, marital commitment, the increasingly febrile identity, ageing, fluid sexuality and the future of gaming and virtual reality technology. As the global community increasingly embraces 5G platforms and our obsession with sleek gadgets reaches fever pitch, now is the time for Black Mirror to be studied and accorded its rightful place in academia.

For those keen to indulge in literary analysis, Black Mirror is the perfect television show to turn to. “Striking Vipers” certainly ranks as one of the top Black Mirror episodes, joining such greats as “San Junipero” and the dating app episode “Hang the DJ”.

The hallmark of Brooker’s dystopian sci-fi tales is the ingenuity with which they tell personal narratives that most of us can engage with and relate to. With trademark Brooker wit and cynicism, the episodes interrogate and engage with our seemingly mundane interactions with technology, teasing out what-if scenarios: What if our obsessions go unchecked? asked the “Arkangel” episode (Season 4, episode 1). Arkangel was the name of a microchip implant that enabled a parent to track and monitor their children. This helicopter parenting had disastrous consequences. It is for raising such pivotal contemporary issues, its on-point commentary on current culture and its exploration of the technology-induced fears that we are projecting onto the future that Brooker’s work deserves recognition in academic circles. After all, how is it different from a work of literature? In my opinion, Brooker’s series has acted as a communal conscience, exploring how our obsession with sleek devices may ultimately be our bane.

[image error] [image error]

Charlie Brooker at the RTS awards. Photo: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Sharealike Generic/ Feline_Dacat – https://www.flickr.com/photos/feline_...

The very title is loaded with subliminal meaning. It references the colour of our smart phones, personal computers, laptops and tablets, looking back at us as we confront our dark thoughts. However, the show is much more than just a cynical scapegoating of technology, as romance-themed episodes like “San Junipero” and “Hang the DJ” have shown. “Smithereens”, the episode that follows “Striking Vipers”, does, however, call out the collective recklessness of our social media culture, particularly our mobile phone obsession as we relentlessly stare at the screen when prompted by Twitter or other notifications. In “Smithereens”, this obsession has a disastrous and tragic outcome when Chris (Andrew Scott), the main character, is involved in a car crash that claims the life of his girlfriend. But Brooker also takes a swipe at the operations of the global media conglomerates in this episode, particularly data harvesting and the manipulation of our personal data in collusion with law enforcement agencies.

In “Striking Vipers”, Danny (AnthonyMackie of Avengers fame) shares an apartment with his girlfriend, Theo (Nicole Beharie), and his philandering pal, Karl (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II). The two friends are polar opposites: Danny is broody and somewhat introverted, living in his own world to which he blissfully retreats, whereas Karl is gregarious and bombastic. Their friendship is boosted by their affinity for the video game Striking Vipers, a Street Fighter-like battle game which they play together incessantly. The game becomes the centre piece of the narrative.

ADVERTISEMENT

An 11-year time jump introduces the audience to a 38-year-old Danny on his birthday. Although Danny and Theo have an adorable five-year-old son, they are battling conception problems. A “blast from the past” encounter with Karl re-ignites the two friends’ video game passion in the form of a revitalised, virtual reality Striking Vipers X upgrade game, which Karl gives Danny as a birthday present. This virtual reality game ushers in untold upheaval and disharmony in Danny and Karl’s lives as they engage in an immersive, virtual world of adult sex games through their respective avatars: Karl as the scantily clad Roxette (Pom Klementieff, who played Mantis in the Guardians of the Galaxy films) and Danny as the muscular Lance (Ludi Lin). Brooker’s intelligence goes into overdrive here, as the duo’s addiction to this virtual reality game introduces such contemporary themes as virtual infidelity and repressed (homo)sexuality.[image error]

LGBTQI+ flag Photo: Shutterstock

The virtual world begins to have a detrimental effect on Danny’s marriage, compounded by the fertility issues they are dealing with. Karl’s remark – “So, guess that’s us – gay now”and their continued annual trysts at the end of the show are evidence of the two male protagonists’ struggle to come to terms with their fluid sexuality. Theo and Danny embrace the “open relationship” notion by openly cheating on each other once annually, by mutual agreement. The open relationship phenomenon is another facet of modern-day life that television consumers can relate to.

“Striking Vipers” poses serious questions – the fluidity of sexuality, complex friendships and identities, and the place and scope of marital commitment, among others. Offline, when Karl and Danny try to re-enact their virtual reality romance with a real-life kiss, it ends with both being embroiled in fist fights. Is this a denial of their repressed sexuality? Paradoxically, outside of their online liaisons, the two men continue to have relationships with women, Danny with his wife and Karl with his girlfriend Mariela. But these heterosexual relationships suffer. In a poignant wedding anniversary exchange in a restaurant, Theo tearfully chides Danny for being unloving towards her, saying she feels rejected when “you withdraw into your own world” at will. Karl, on the other hand, fails to sexually fulfil his girlfriend. “Striking Vipers” appears to be interrogating the complexities of new sexual possibilities in an increasingly digitised global landscape. Interestingly, “StrikingVipers” could be read as a metaphor for Danny and Karl’s desires. There is little doubt, though, the show offers a nuanced portrayal of marriage.

Watch the trailer for Black Mirror: Striking Vipers

ADVERTISEMENT

What makes “Striking Vipers” poignant is that it could be happening in our contemporary society. Why a simple virtual reality fight game should double as a sex sim is an important question that the show proffers. Equally, the question of why fantasy underlies so many virtual worlds presents itself. Avid gamers know what it is like to live vicariously through our onscreen avatars, so we can identify and feel for both Danny and Karl as they live out their fantasies in an imaginary world. Of course, there are risks to living in a parallel universe or fantasy world, as the episode ultimately shows.

“Striking Vipers” taps into how many people are living or playing out their lives in the virtual world and how this “other life” may interfere with or impact on their real or offline world. Sociological research by Boellstorf (2008) and Carter’s cyber city notion (2005), for instance, has long shown how people like to hide behind the façade of virtual worlds or in a “second life”, as Boellstorf terms it. This escapism allows them to fulfil their fantasies in a way, but not without consequences – as the end of “Striking Vipers” illustrates. Following his off-screen confession, Danny and Theo’s marriage will never be the same again. As Carter (2005) observed from her research, ‘People are investing more time in online relationships and are likely to continue these relationships in their offline lives and meet in person.’

The American cable and satellite network Showtime’s show Dark Net has dealt with similar issues before. For instance, a Japanese man, the main character, dates and falls in love with an avatar character Rinko and introduces “her” to his mum. He uses LovePlus sim to achieve this. LovePlus isa dating sim originally developed for the Nintendo DS handheld video game console. In recent years, the rise in artificial intelligence has seen the sex industry resorting to robots to aid a burgeoning market. Increasingly, the world abounds with trends such as catfishing and sexting, among other forms of online role playing, in which people seem to enjoy the façade of an assumed online persona.

So, when Brooker highlights these very issues that are present in our contemporary reality, then the world of Black Mirror should not be dismissed as an exercise in hyperbole. If anything, we are living in this world; it is not far-fetched.[image error]

BlackMirror Title Card. Photo: Wiki CC

Take the example of another Black Mirror cracker of an episode, “Nosedive” (Season 3 episode 1). It fully validates our existential reality. “Nosedive” takes pot-shots at our obsession with the online ratings system, amplifying it as an oppressive, society-wide status game. I for one can see my own experience of this on the multitude of online shopping portals, such as Amazon retail, or airline websites, when I studiously check out previous customer reviews as a basis for making an informed purchasing decision. I am not alone in this.

In Black Mirror, Brooker, with his technological determinism thrust, tends to replicate our collective fear of technological difficulties in the future. In essence, Brooker is saying, our sleek technological devices, be they smart phones, TV flat screens, laptops, tablets, or video games, do define and shape our present-day reality. In addition, “Striking Vipers” also deals with vital issues that underpin our humanity, such as sexuality, honesty, trust and communication in relationships. While opinion may be divided, Brooker does manage to make his point well, highlighting techno-paranoia, the technological possibilities of the future and the negative effects these may have on humanity. I, for one, believe that his artistic output will stand up to and is worthy of scholarly scrutiny.

Author’s Bio:

Andrew Chatora teaches English, Media and Sociology at The Bicester School in Oxfordshire, England, where he manages The Media Department. He writes here in his personal capacity.

The post Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror: Fluid identities – life beyond virtual reality appeared first on Andrew Chatora .