Andrew Beahrs's Blog

June 7, 2015

Bobotie!

After I shared this recipe with my sister in North Carolina, she wrote back that “The bobotie was so damn good. And like nothing I have ever cooked before! Thank you. If you ever think ‘hey this recipe is unusual and a novice could do it without getting stressed out and people should know about it’ please send it along.” Here’s the recipe that got her so excited.

Bobotie (a lightly curried lamb or beef casserole) is South Africa’s national dish, and it’s absolutely fabulous. This version was passed on by my old Archaeology professor Jim Deetz, who used to packrat all the best recipes he found in newspapers and on labels, and eventually compiled his favorites into a cookbook that family (and some students) were lucky enough to get copies of. As you can see mine is dog-eared, stained, and much-loved, and this is one of my favorites from it…we made it for New Years Eve about five years running. Enjoy!

Bobotie

1 Tbs oil

1 medium onion, chopped

2 lbs lean ground lamb or beef

2 garlic cloves, crushed

1 1/2 Tbs curry powder

1 cup beef stock

2 Tbs soy sauce

2 Tbs mango chutney

3/4 cups slivered almonds

3/4 cups raisins

1/2 tsp thyme

salt & pepper to taste

5 eggs

1 cup milk

nutmeg

Toppings: chopped tomatoes, bananas, coconut, chutney

steamed rice

Heat the oil and cook onions until softened.

Add beef and brown over moderate heat.

Add garlic and curry powder and cook for one minute.

Add beef stock, soy sauce, chutney, almonds, raisins, thyme, bay leaf, salt and pepper.

Simmer for 45 minutes. The consistency should be moist and holding together.

Remove the bay leaf, spoon into casserole and smooth over the top.

In a small bowl, beat eggs and milk together; add a pinch of nutmeg, salt and pepper.

Pour custard over the meat mixture.

Bake at 350 degrees for about 30 minutes, or until custard is set.

Serve with chopped tomatoes, bananas, coconut, chutney, and rice.

May 13, 2015

Viking Syndrome is a Major Disappointment

You’d think that something called Viking Syndrome would at least have the grace to be badass–that it would be a shoulder condition first identified among those accustomed to swinging broadswords, or an effect of sleep deprivation described in sagas of crossing the frozen North. Instead it turns out to be a few hard nodules in the palm of your hand, that just happen to be more common among males of Northern European descent–especially so among those just over 40. That places me right in Viking Syndrome’s wheelhouse, so I guess it’s no surprise that I’m developing a textbook case on the palm of my right hand.

This is not, as yet, a problem at all. It’s easily detectable–even visible, now, as the skin about the nodules tightens and wrinkles–but not painful in the least. It may become one down the line, though; sometimes the nodules draw the tendons of the fingers so tight they curl over and become useless (it’s also called Dupuytren’s Contracture) If it ever gets to that point, there are some treatments available, and until it does I can take solace in that fact that my chosen banjo style is called clawhammer because the right-hand playing position is curled up like much like the middle stages of Viking Syndrome

What it brings home to me is that I’m perhaps overly attached to the idea of improvement. When I’m playing an instrument, taking up a new sport–anything–I lose interest pretty quickly if it doesn’t seem like practice or repetition will show some perceptible results. That’s OK as far as it goes–life is short, we have to choose where to put our time, and on and on.

But it can also verge on being self destructive. If the Viking’s progresses, and proves resistant to treatment…well, that’s a huge check on my ability to get better at any number of activities. But so what? Eventually all skills plateau and finally decline; eventually, for whatever reason, we all play the last chord we’ll ever play. There’s no reason to end sooner than necessary because of some false, unattainable ideal of continual and ongoing improvement.

I’ve already caught myself thinking that there’s no point in learning a bit of piano when I don’t know what my hand’s going to be like in five years. I think for that very reason I should probably start making some time to practice some…the habit of talking myself out of things is one that I definitely don’t want to cultivate.

April 27, 2015

Pruning

I spent part of the weekend pruning our fruit trees. Northern California weather makes it easy to grow fruit in abundance (except, of course, for the rain situation, and greywater takes care of most of that as well) and we’ve taken advantage of that by putting in a pair of figs, a couple of apricots, four apples, and two soon-to be removed pears (can’t win ’em all). Ten trees in a single modest front yard isn’t as space-consuming as it sounds–we chose trees with similar root systems then planted them in pairs within 18″ of each other, so the roots natural competition helps to stunt their growth. Still, there’s no way around thrice-annual pruning sessions, which have gradually become one of my favorite ways to spend an afternoon.

It was daunting at first. It’s hard to get past the notion that dramatic cuts would not only hurt the tree, but eliminate a huge amount of the longed-for fruit. Once I understood the logic of pruning cuts and something about the growth process of trees, though, it got fun–even therapeutic–right away. Cuts aren’t really cuts, after all; cuts are growth. Take a limb, and watch how the tree sends all its force to the nearest remaining bud, sprouting and re-filling the space left behind. Open the center, and see how everything around it goes flush from air and light. After a while you realize that there’s as much tree underground as above it, and the tree wants those two parts to balance, so after a good prune it comes back strong with healthy new growth, hopefully right where you wanted it. Pruning is a conversation with the tree, a kind of call-and-response that plays out over years, and it’s enormously relaxing.

Writing is like that too, I think. At first it’s hard, almost impossible, to cut a line you like, let alone a character or a scene or a chapter or what have you. Is this is the good stuff? Have I just gutted the piece? Those questions are completely natural, and can be paralyzing.

But you know how often the answer to either one is actually Yes? Never. I like working off hard copies, switching back and forth between a word processor and editing and printout and writing it all out in longhand and finally typing it all back up. That process uses up a lot of paper, and I rarely if ever recycle until I actually ship a piece. After finishing a book I might have 6 drafts sitting by my computer, stacked almost as high as my seat.

And how often do those early drafts offer up material I dearly wish I’d kept? How often to I reintegrate a line, a character, a scene? I say again: NEVER. It just doesn’t happen. A tree will grow until it’s equal to the roots hidden underground; a piece of writing has a right size, and will grow to fill the spaces left behind by edits. The stuff you cut may have been important at the time, it may have taken you in a crucial direction. But when it’s time to cut it, it’s time to cut it.

You just have to trust that growth will follow. It will.

April 9, 2015

The War of Art

Just finished reading Steven Pressfield’s “The War of Art,” a short, engaging exploration of (and call to arms against) what Pressfield calls “Resistance.” For Pressfield, Resistance is an actively malevolent force that interferes with any creative work. It’s what you feel when you’re surfing the web, doing the dishes, chatting on the phone–whatever you’re doing except sitting down to create. It’s the “enemy within,” and it will “perjure, fabricate, falsify, seduce, bully, and cajole” to stop you; it is “always lying and always full of shit.” Its weapons range from procrastination to sex to the desire for emotional healing–not all bad things, of course, but insidious when they become excuses and rationalizations for not doing the work you dream of doing.

It’s not a perfect book. Pressfield (as you can probably gather) can be grandiose, and this sometimes gets him into trouble; an early line about Hitler finding it easier to start WWII than to face a blank canvas threatened to derail the entire thing.

But that same grandiosity is the book’s greatest strength. Because Pressfield is right: when we write (or paint, or sculpt, or build, or play), we do all face an internal enemy. That enemy does play for keeps, it does mean to kill by stealing life away one moment at a time. And to fight that enemy–that constant voice saying can’t, won’t, not now, not good enough–you have to start by admitting to yourself that the stakes really are that high. Pressfield gets that, and I’m grateful to him for laying it out in such plain and convincing language.

So: he got me. I took a lot away from this book, and I think other writers and artists (and really, anyone who wants to create) will too. You might roll your eyes at some of the language, but at the same time you’ll recognize a whole hell of a lot of what he’s talking about. And if you’re like me, the next morning it’ll be that much easier to sit down and get to work.

April 1, 2015

The Windcatcher is out!

Fifteen years ago I sat down in the house I shared with my soon-to-be wife in Charlottesville, Virginia, and read a story in Farley Mowat’s Sea of Slaughter that changed my life. In the early days of colonial America, Mowat wrote, a crew of eggers searching for Northern Atlantic nesting grounds had found a young woman living alone among birds and “white” bears on a small, rocky island. Mowat’s book was about rapacious hunting and fishing, so he was mostly interested in the auks and in fact that polar bears lived almost as far south as Newfoundland.

Fifteen years ago I sat down in the house I shared with my soon-to-be wife in Charlottesville, Virginia, and read a story in Farley Mowat’s Sea of Slaughter that changed my life. In the early days of colonial America, Mowat wrote, a crew of eggers searching for Northern Atlantic nesting grounds had found a young woman living alone among birds and “white” bears on a small, rocky island. Mowat’s book was about rapacious hunting and fishing, so he was mostly interested in the auks and in fact that polar bears lived almost as far south as Newfoundland.

But I couldn’t get my mind off the woman. Who she was, why she’d been abandoned…the questions were impossible to shake. When I sat down to read I’d been a third-year graduate student in archaeology, but when I stood back up I was determined to become a historical novelist; this, I thought, was the story I wanted to tell.

Now, ten years after the novel’s first publication as Strange Saint, the e-book revolution has given authors incredible new tools and control over their work, inspiring me to revise Strange Saint for electronic release. During the process I came to see e-books and paper books as closely related, but nevertheless distinct, formats, and even though my edits were largely cosmetic I decided that the changes warranted a fresh start for the novel. Newly titled The Windcatcher, it’s available for the next two days as a free Kindle e-book.

Edits and formatting aside, the heart of the book remains Melode. She fascinated me before I had any idea who she was; she still does today, and it’s a joy to be able to release her story. I hope you’ll take the chance to download the novel while the promotion is on, and that you enjoy reading it as much as I did writing it.

March 22, 2015

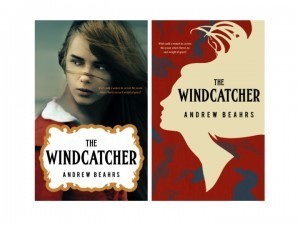

New covers

Working with Kerry Ellis on the new covers for The Windcatcher  has been a total joy. She produced these two fabulous images, which I love in such different ways; the first time I saw the one on the left I did a double take at how perfectly Melode the girl is, but the more abstract art captures much of Melode’s spirit and lets the reader fill in the details of her appearance for themselves. A very tough call ahead, but I’m feeling extremely lucky to be working with a designer who got right to the core of the book and returned with two terrific, but very different, designs.

has been a total joy. She produced these two fabulous images, which I love in such different ways; the first time I saw the one on the left I did a double take at how perfectly Melode the girl is, but the more abstract art captures much of Melode’s spirit and lets the reader fill in the details of her appearance for themselves. A very tough call ahead, but I’m feeling extremely lucky to be working with a designer who got right to the core of the book and returned with two terrific, but very different, designs.

March 11, 2015

Melode Speaks

A month ago, I picked up Strange Saint for the first time in probably seven years. Now, putting a piece of work aside for extended periods has always been part of my writing process; there comes a point when that’s the only way to clear my head so that I can the story as a whole. But this was different; entire passages, or even characters, seemed as new to me as though they’d been written by someone else. It was a new, and exciting, experience to plunge into the world of the book after so long away from it. For the first time I could enjoy it as a reader rather than a writer.

But what I mostly felt was guilt. Not guilt for having been away from the book–life is short, and there are a hell of a lot of books I should be spending my time reading before coming back to my own. I felt guilty for having abandoned Melode.

When I first started writing Strange Saint, I was working with the bones of a true story recounted in Farley Mowat’s Sea of Slaughter: during the early colonial period, a young woman was marooned on a subarctic island, where she survived for more than a year. Mowat found the story interesting because of the polar bears on the island (the island was far to the south of the bears’ current range, which suggested that their designation as “polar” was due to their having been hunted out of warmer climes).

But I was fascinated by the woman: who she was, what she wanted, why her companions left her behind. Months into my writing, Melode started to talk–I can’t think of a better way to say it–and when she did, she had the answers to those questions and more. I spent better than a year with her, until finally sending her out into the world in Strange Saint.

My sense of guilt came from my deep attachment to Melode, and my sense that I’d allowed her to languish. This might seem silly (we’re talking about a fictional character, after all), but the truth is that even typing “fictional character” doesn’t feel true. Sure, Melode exists only in the pages of Strange Saint. But she’s real to me, and I felt an immediate compulsion to let her out once more.

So on March 30th, I’ll be releasing Strange Saint in a revised, ebook edition titled The Windcatcher. Prepping the book has been both challenging and enormously exciting; the indie publishing revolution has given authors a previously-unimaginable–and sometimes daunting–amount of control over their work, and working on this revision has made me even more grateful for everyone who worked so hard on the previous, traditional release. It feels like the first step on a whole new journey, one that I’ll be continuing with a new ebook edition of The Sin Eaters, the all-new historical fantasy novel The Big South Country, an as-yet-untitled novel about the orphan who helped to create the idea of a truly American cuisine, and more.

It’s all because of Melode. As she reminded me when I opened Strange Saint after so long, she’s never been one to stay quiet, or still; now she’s not going to have to.