Anthony Metivier's Blog

September 2, 2025

Memory Training Techniques: 7 Useful Daily Drills and Exercises

If you’re seeking memory training because of forgetfulness, mental fog, or information overload, you’re not alone.

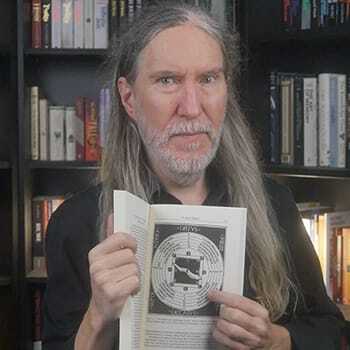

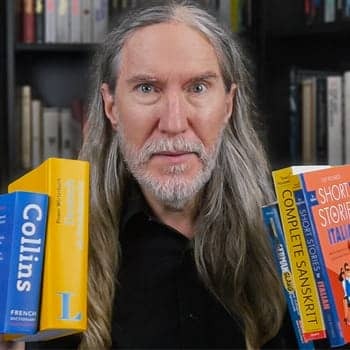

In fact, I’ve been on both sides.

I’ve been so frustrated with my memory that I nearly dropped out of grad school.

And so successful I came in second in a memory competition against one of the best mental athletes in the world.

My range of experiences means good news for you.

With the right daily drills and proven exercises, you can dramatically improve your recall, focus, and clarity.

In this guide, you’ll discover 7 memory training techniques I’ve personally used to:

Complete a PhD using mnemonic strategiesDeliver a TEDx Talk seen by millionsLearn multiple languages with confidenceEach routine is practical, research-backed and useable starting today.

Whether you want to remember names, prepare for exams, or simply keep your mind sharp as you age, these drills work.

Let’s dive in.

Proof that Memory Training WorksAs we go through the list of memory techniques you can start practicing with today, keep in mind that there’s no particular order of importance.

They all matter and each one is well-worth spending time learning.

But you might like to have some assurance that scientists have actually studied these memory tools.

In addition to reading my full profile of the state of memory science, you’ll be delighted to know that many of my memory champion friends have participated in memory studies.

For example, Katie Kermode recently posted on LinkedIn about her participation in this University of Cambridge Study.

This study follows many others, including a major analysis of how proper memory training leads to superior memory skills.

I’ll share a few more scientific references as we go, but for now, keep in mind that we are talking about training.

This means that your time does need to be spent on learning and applying the various memory techniques we’re about to explore together.

But every moment will be worth it once you see the results of better memory flowing into your life.

The Core Memory Training Techniques & Drills I RecommendOne: Mnemonic LinkingMnemonic linking is where most people start training their memory.

What is linking?

It’s a simple technique where you assign vivid, strange or emotional associations between information you already know and new data you want to retain.

To keep things simple, let’s say you need to remember a list of words like “apple,” “book” and “dog.”

To use the linking technique, you simply mentally link the apple with something related to apples that is specifically familiar to you. I would personally forge a link with an Apple computer.

For the next word in the list, I would imagine the Apple computer interacting with a specific book. Since the final word is “dog,” that book could be the Bible in the jaws of a specific dog.

The key is to make every association specific. So in this case, the list will be easiest to remember if there’s a kind of mnemonic story playing out:

“An Apple computer flies down from the sky to try and wrestle the family Bible from the jaw of Superman’s dog.”

Silly, right?

Yes, and that’s what makes it so memorable.

In case you’re interested, one of the reasons why so many people start with linking isn’t because it’s the best place to start.

It’s largely because that’s where the dominant memory improvement authors like Harry Lorayne and Tony Buzan talked about starting. They were largely repeating the instructions given by Bruno Furst in his correspondence memory courses.

Linking is definitely worth learning. I use it frequently and found it especially helpful for learning the articles and other aspects of learning German.

Two: Peg SystemsPeg systems are the foundation of how I learned to memorize playing cards.

Please be aware that memory teachers use the general term “peg” in quite a variety of ways.

I generally call it the pegword method and separate pegs into at least four different kinds of mnemonic images:

Number RhymesNumber objects (or number shapes)Major SystemPAO SystemTo give you an example of the simplest peg system, here’s how the number rhyme technique works through the association of rhymed images:

1 = sun2 = shoe3 = bee4 = door5 = hive6 = sticks7 = heaven8 = gate9 = wine10 = henAs a fun exercise that will itself give your brain a workout, I suggest you draw your first number-rhyme list.

Here’s my own hand drawn list:

Once you’re set up with these rhymes (or variations of your own choosing), associating information using this technique will be a breeze.

To give you an example, let’s refer back to our previous list.

Using number rhyme pegs, you could imagine the apple growing as large and as bright as the sun. The book could be shaped like a shoe, and smell just as bad. And the dog could be chasing bees.

The advantage to number rhymes is that you not only remember the items. You also remember the numbered order of each item in the list.

Another advantage when you develop your skills will all four peg systems is that you have pre-learned mental associations.

You don’t have to invent new links on the fly. You have mental “pegs” to hang new information on.

Please train with all of these peg systems in the bulleted list above because having multiple tactics offers tremendous flexibility when you want to remember things quickly.

Three: Keyword MnemonicsWhen preparing for my TEDx Talk, I didn’t memorize every word.

Instead, I pulled out only the most important words. This is generally the best approach to memorizing a speech.

By compressing the speech into a smaller set of memory triggers laid out along a Memory Palace journey, I was able to convey the main points without having to memorize the entire speech verbatim.

As a result, you can memorize two or three words and still recall entire sentences.

For example, my TEDx begins with the line, “How would you like to completely silence your mind?”

The images are simple Howie Mandel with a stick of wood hitting a like button on a YouTube video. Since I know the topic of my talk, I didn’t need to encode the rest of the phrase.

Verbatim Memorization By Making Every Word a KeywordNow, if you’ve seen my TEDx Talk, you might have noticed that I recite a few quotes and Sanskrit phrases.

This is verbatim memorization, but it’s essentially the same process.

Instead of extracting keywords, every word is memorized as if it were a keyword. To practice this, I suggest you complete my tutorial on how to commit poetry to memory.

As an additional resource, please consult my detailed tutorial on how to memorize a paragraph.

Four: Alphanumeric MnemonicsI mentioned the Major System above.

Let’s dig deeper into how this technique works so you can easily remember important phone numbers, credit cards, historical dates and even matters related to programming on demand.

What is it?

The Major System is called an “alphanumeric” technique because it helps you transform numbers into consonant sounds.

You then turn these into memorable words by inserting vowels between the consonants.

The Major System is a foundational technique and merely learning to use it will provide you with outstanding memory training.

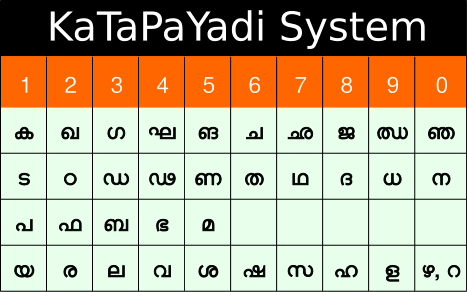

Here’s the exact alphanumeric pattern I’ve used for decades:

The Major System

The Major SystemOnce you’ve committed this set of associations to memory, here’s how it works:

If you have to memorize the number 34, you note that 3 = M and 4 = R.

You then insert a vowel and come up with a word like “mare” or a person like “Mary.”

Personally, I use “mare” as my word for 34, but make it more specific by thinking of a specific horse: the one pictured on the cover of Piers Anthony’s Xanth novel, Nightmare.

Although this technique is primarily used for remembering numbers, you can actually use it to remember many other things.

For example, often when I learn new words in different languages, I observe the consonants and work out what numbers they would be in the Major System.

This makes it fast and easy to come up with associations.

For example, in German, “blacksmith” is der Schmeid.

In the major, the “sch” sound can be represented by 6, which also covers J sounds. D is linked with 1.

61 makes words like “Jedi” and Judd. So I can imagine the actor Judd Nelson “smushing” his Jedi uniform into a suitcase shaped like an E.

Although that’s not 100% direct, it doesn’t have to be. With a small amount of spaced repetition, the target information will enter long-term memory.

A Brief History of Alphanumeric MnemonicsAlthough it can be a bit tough to learn in the beginning, rest assured that people have been using mnemonic tools like the Major System for thousands of years.

For more background, check out Lynne Kelly’s The Memory Code.

In my own research, I’ve found the katapayadi system, which goes back to at least 869 CE.

I find the length of time this particular type of tool for establishing memories has been around inspiring. Hopefully it will continue to survive for both practical uses and fun projects like memorizing pi.

Five: The First Letter Mnemonic TechniqueThis next technique is great for training with poetry, song lyrics and quotes.

To use it, all you do is take the first letter of each word and write it on a piece of paper.

Here’s what I mean using the opening of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 59:

“If there be nothing new, but that which is hath been before…”

Once you’ve written out the letters, you look at the list and practice recalling all the words in full.

It is literally an exercise in mentally filling in the blanks.

As a learning technique, this approach is related to the Cloze test.

In this laboratory study of using what the scientists called the “first Initial mnemonic,” students who used it as part of their studies showed significantly better recall.

Although I would never use this approach to memorize something mission critical like a speech, it is a good training exercise. I use it a couple of times a year just for practice.

Six: Story-Telling For Better MemoryI mentioned the power of crafting mnemonic stories above. Let’s go deeper.

As we know from the story of Simonides of Ceos, the brain loves stories because it finds them instantly memorable.

That’s one reason why the Renaissance memory master Robert Fludd talked about using theatre plays in your associations.

I personally use this approach often, and have a full Story Method tutorial that will help you use it in a highly targeted way for both training your memory and as a learning tool.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YhN0r...

Seven: The Memory Palace Technique (The Gold Standard)The Memory Palace technique changed my life.

Also known as the method of loci, it’s powerful because it lets you use one of our most powerful types of memory and mental faculties:

Spatial memory.

In other words, you place associations paired with your target information along a familiar route or location in your imagination.

Then, using spaced repetition and one of the association techniques discussed above, you revisit the images you placed along the journey. Soon, you’ll have the information you want to remember in long-term memory.

That’s exactly what I did to memorize my TEDx Talk using keywords after making a quick sketch of a familiar location:

And like all memory techniques, the Memory Palace has been thoroughly vetted by researchers.

According to a Nature article prepared by Eleanor Maguire and her team, anyone can reshape their brain’s networks by using this technique.

As the scientist’s revealed when sharing the brain scans of memory champions who use the technique, their success in remembering vast amounts of information quickly came from using this spatial memory technique.

The researchers then put non-memory athletes through a memory training program and observed how their brains changed with exercise.

The more the newcomers practiced the memory training techniques, the more their brain activity started to resemble the brains of memory athletes.

That means you can expect similar memory boosts, even if you’re a beginner with this particular mnemonic device.

Beyond Training with Techniques: Daily Memory ExercisesDeveloping stronger memory skills is generally best approached using the techniques I just shared with you.

However, there are other smaller actions you can take to create remarkable results over time.

Here are some recommended daily memory-boosting exercises I personally use and recommend:

One: Brain Games and PuzzlesYou can stimulate multiple aspects of your cognition by playing a variety of brain games.

In addition to the classics like Sudoko and matching games, you can get involved with my Memory Detective game. We usually play a round every Halloween in the Magnetic Memory Method community.

Two: Regular Mindfulness and MeditationEven just ten minutes a day of sitting meditation can improve your focus and working memory.

As this study shows, less is definitely more.

Not only did they find that brand-new meditators enjoyed better memory. They also experience mood boosts and greater levels of emotional regulation.

Three: Physical Exercise for Brain HealthAlthough I don’t always feel like it, I work hard to get myself to the gym three times a week. Or I will do a calisthenic routine at home.

I also take walks almost every day, including walking backwards. As this study showed, even just imagining that you’re walking backwards produced a memory boosting effect.

Personally, I prefer the real thing, even though it gets strange glances when I do it at the local outdoor gym.

Four: Learn Something New Every DayWhether it’s studying a new language, a musical instrument or practicing a hobby like writing, continually learning new topics and skills keeps your brain engaged.

It also helps with neuroplastic change, literally rewiring your brain for better processing speed and memory.

You might also consider exploring a variety of ways to learn. If you typically take notes in a top-down fashion, for example, you can spend a few months on Tony-Buzan style mind mapping for a change.

Frequently Asked QuestionsOver the years, I’ve received dozens of questions about various memory activities.

Here are answers to some of the most useful.

Does memory training really work?The nuanced answers is that any memory exercise you engage in will work relative to the effort you put into it and the level of challenge.

Often people complain that a mental training routine isn’t producing results, but they are not actually challenging themselves in any meaningful way.

For example, in my critical analysis of crossword puzzles as a memory activity, you’ll find research showing that many people weaken themselves by looking at the answers.

So if you’re following a routine that lets you cheat in any shape or form, then no, it’s not likely to work.

The flip side of the coin is that you don’t want to engage in activities that are so challenging you simply feel frustrated.

So I encourage you to find activities that are challenging, but not to the point of constant failure.

How long does it take to see results?If you choose a memory training exercise like the first letter mnemonic we discussed above, you could feel the results instantly.

But generally, there’s no magic number.

The point of memory training is similar to physical training. You want an ongoing balance of new exploration and maintenance of existing skills.

Are brain training apps the same as using memory techniques?Not at all.

This is because the point of memory training is ultimately to have sharper recall in situations where you can’t reach for a device and use a search engine.

As I discussed in my post on cognitive training myths, you want some alignment between your specific memory improvement goal and the improvement activities you choose.

So if you truly want to improve your memory, think about exactly what that means. As I discuss in my tutorial on how to increase memory power, you need to start by defining your memory improvement goal.

Then select the activities most likely to get you there. Chances are, it won’t involve an app.

Can memory training help me pass exams?Absolutely. People who regularly train their memory skills will gain an advantage.

But let’s be clear:

There’s a difference between daily training trills and sitting down to commit testable information to memory.

Just because you’ve sharpened your memory doesn’t mean you’ll memorize test answers.

For that, make sure you consider the techniques for studying I used when completing my PhD more comprehensively.

Memorization was a substantial part of my process, but not the only activity I engaged in by far.

Will memory training help reduce the impact of aging?Almost certainly.

But you definitely want to discuss any issues you’re experiencing with a doctor.

As you do, please take inspiration from some of the greatest memory instructors who ever lived.

Harry Lorayne wrote many fantastic books on his way to the ripe age of 96 years.

He provided complete proof of concept and shared his best memory training processes in a book called Ageless Memory.

Likewise, Tony Buzan remained sharp during his twilight years. I re-read The Memory Book frequently to continually take inspiration from how he combined memory training with physical activity and diet.

What is the best memory training technique for beginners?I suggest starting with number rhymes and applying them to simple lists.

It’s quick to setup and wonderfully effective.

Once you have the system setup, the only remaining task is to select various words with which to practice on a daily basis.

Fortunately, that’s as simple as picking up a dictionary or visiting a website that will suggest words for you.

Final Thoughts: You Don’t Need a “Photographic Memory”Many people ask me to teach them to have a photographic memory.

I always turn them down because most of what we need to memorize is in language, not pictures.

Plus, photographic memory is widely considered to be pseudoscience.

Ultimately, if you want a trained memory, or even just to learn faster, every technique you’ve discovered on this page is very learnable.

If you’d like more help, especially with turning these exercises into long term results, sign up for my free course now:

It gives you the ultimate memory improvement exercise by focusing on spatial memory through four free videos and three powerful worksheets.

You’ll learn how to:

Lock information into long-term memoryRecall faster with less effortTransform more of your studies and work life into effective brain workoutsAnd if you’d like more information on additional mnemonic tools, this list of memory techniques goes deeper still into the many mnemonic activities you can explore.

The important point is to get started and keep going.

The absolute best years of your learning and remembering life await!

August 8, 2025

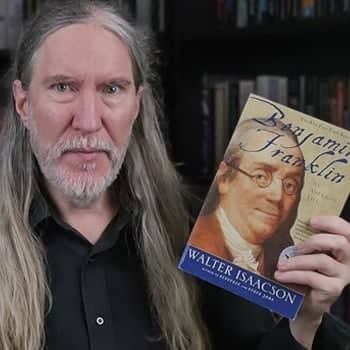

The Learning Habits That Made Benjamin Franklin a Polymath

How did the runaway fugitive Benjamin Franklin become a writer, printer, inventor, philosopher and diplomat and still find time to help found the United States?

How did the runaway fugitive Benjamin Franklin become a writer, printer, inventor, philosopher and diplomat and still find time to help found the United States?

Part of the answer is easy: he was a self-made polymath.

That means he trained himself to study and succeed in multiple skills and disciplines with surgical focus.

The key to learning across so many fields?

Habits.

Routine processes and procedures that still work to this day.

In fact, they’re more valuable than ever.

On this page, you’ll learn how Franklin built one of the sharpest minds in all of human history.

Even better:

You’ll learn how you can use the same habits and techniques to learn faster, think deeply, and integrate knowledge across multiple fields.

Let’s dive in.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2tQm-...

What Makes Benjamin Franklin a Polymath?The term “polymath” has been used for hundreds of years to describe a person of various learning.

But we’re not talking about productivity nerds, which is sometimes how the term is now used in our time.

Franklin, like Thomas Jefferson and other polymaths I’ve covered on this website, built expertise in multiple areas through the power of habit.

It’s important to understand this fact because Franklin was not born into privilege. He wasn’t a savant.

But the specific activities he engaged in make him one of the most influential minds of his time. He influences us to this day.

And his learning habits are proof that polymathy isn’t about talent. It’s about practicing the right habits.

Benjamin Franklin’s Most Important Learning HabitsAs we get into my discussion of how Franklin learned, you might think that some of the habits I’m describing belong more to the realm of productivity.

Although that might be true, to succeed in everything from science and innovation to politics and diplomacy, Franklin’s biggest habit is the most important of all.

That’s because it creates reflective thinking. And when you have that, you learn from your own habits, enabling personal growth over time as you learn from your own journey.

With that point in mind, here are what I believe are the most important lessons about learning, overcoming obstacles and long-term focus.

One: The Focusing Power of Franklin’s Reading DeadlinesFranklin worked for a time in his brother’s printing shop.

To educate himself, he would quietly borrow books from apprentice booksellers and read them overnight. Then, before anyone noticed, he would return them.

As he wrote about this habit:

“Often I sat up in my room reading the greatest part of the night, when the book was borrowed in the evening and to be returned early in the morning, lest it should be missed or wanted.”

This early habit of reading against the clock focused his mind and deepened his memory.

He also chose books written in modern styles, which would influence his communication skills.

But the point is that Benjamin chose to become one of the most well-read minds of his era.

And when he read, he wasn’t just reading. He was training.

I’ve also read against the clock for years and deadlines are indeed powerful. Check out my guide to reading faster for more information.

Two: The Expansive Power of ConversationFranklin didn’t just read books. He also read people.

That’s because he understood something that many people who want to become polymathic miss:

The right conversation with the right person can teach you more than a hundred books. Faster.

In order to make sure he was having plenty of the right conversations, Benjamin created the Junto in Philadelphia.

This was a weekly discussion group where a variety of tradesmen, writers and thinkers shared ideas.

It was not just a social circle.

Rather, the Junto was a living, breathing social system that allowed its members to learn from one another.

As Jessica Borger recently wrote in a scholarly paper titled The Power of Networking in Science and Academia, networking remains just as important in our time. If not more so.

As Franklin wrote with reference to the importance of relationships:

Three: Accumulating Knowledge Through Questioning“A man wrapped up in himself makes a very small bundle.”

Franklin wrote a lot and was clearly highly opinionated.

But Walter Isaacson highlights in his excellent biography, Franklin wrote that knowledge “was obtained by the use of the ear rather than of the tongue.”

To make sure he had plenty to listen to, Franklin stimulated conversation through questions.

If you’d like to emulate the process, check out my full guide on how and why you should question everything.

The key is to understand that Franklin didn’t ask questions to impress others.

He used dialogue to help refine his thinking, uncover new perspectives and help himself and others understand more.

All the reading to deadlines he did surely helped stimulate his curiosity and stockpile a number of questions.

But the deliberate practice of questioning helped make the process automatic, literally forging it into a habit thanks to what scientists call procedural memory.

Make questioning while you meet with people and as you study a habit of mind. It will help you think differently, learn more and experience tremendous growth.

And the best part is that the more you practice asking questions, the better your questioning will become.

Four: Setting Rules and Keeping ThemJust as reading to deadlines focuses the mind and memory, developing codes of conduct frees the mind to pay much more open attention to what you want to learn.

That’s why Benjamin was a fanatic for creating rules.

But he didn’t just create them.

He wrote them out, tested them, enforced them and evolved them over time.

For example, he crafted thirteen rules around a list of virtues. You can find them in his autobiography, specifically the section where he talks about his goal of achieving moral perfection.

But he didn’t stop at self-discipline for himself.

When he formed the Union Fire Company from a group of volunteers, he wrote bylaws. If members broke the rules around attending meetings or taking care of equipment, they paid fines.

Likewise with the Junto. Members followed written rules to help ensure an environment where their mutual focus on learning from one another thrived.

You might think Franklin’s approach is a bit old-fashioned. But in our time, internet companies like stickK enable people to set up commitment contracts. If they don’t achieve goals they’ve set for themselves, the company will send a certain amount of the users money to a charity or other designated party.

Although your mileage may vary from setting rules for yourself, habitually setting up codes of conduct and sticking to them can create a framework for learning.

Personally, I use rules as accelerators for my learning goals often, such as rewarding myself for getting through difficult books I don’t want to read. For example, I won’t let myself get a book for pleasure until I’ve finished one that I’ve committed to completing for my research.

I find that accountability works best when it’s unavoidable, visible and public. That’s one reason I made a video about my in-progress bookshop Memory Palace project.

Although many challenges have made me want to give up along the way, my rule that I finish the projects I start helps me push through. As does making the projects I start public.

Five: Masterful Note-TakingAs a student of multiple topics, Franklin developed his own shorthand.

These days, you can learn Gregg shorthand relatively quickly, sparing yourself the hassle of creating a system from scratch.

But the larger point is to learn how to take notes effectively.

For picking up this powerful study skill, you can consult my guide to note-taking.

You can also explore one of the core techniques Thomas Jefferson used, an approach now called the Zettelkasten method.

Whichever method you choose, it’s helpful to understand that many of Franklin’s notes were not main points copied out verbatim.

He formulated the ideas in his own words, often reconstructing the ideas in the form of Socratic dialogues.

Franklin even invented names for different personas and had these characters help him explore and refine a variety of ideas.

You can think of this approach as an advanced form of active, transformational note-taking. If you want to be as polymathic as Franklin, avoid passive reading and seek the active synthesis of ideas by engaging them deeply in your own words.

Six: Writing to LearnFranklin didn’t stop at reformulating his notes. He treated long-form writing as a laboratory for learning.

As a self-taught teenager marked by the most common traits of an autodidact, Franklin copied essays he admired.

Then, he would attempt to rewrite them from memory a few days later.

Even more importantly, he studied grammar and rhetoric to help him craft better persuasion skills. As he wrote:

This habit, I believe, has been of great advantage to me when I have had occasion to inculcate my opinions, and persuade men into measures that I have been from time to time engaged in promoting.

Franklin also wrote correspondences with people around the world. When he could not learn from available journals or his social circle, he wrote to thinkers across Europe.

They helped him design his own experiments, and his habit of regularly communicating in writing through the mail was tremendously fruitful.

Writing also helped provide Franklin with a fantastic memory for quotes and short sayings packed with wisdom.

And of course, writing made him incredibly wealthy. This habit literally bought him more books and more time to read them. He retired from his business at just 42 years of age.

Seven: The Synergy of Synced HabitsAlthough we often think of polymaths as people who have established mastery in multiple domains, Franklin unified his skills wherever possible.

His strategies for competing with a fellow newspaper printer named Andrew Bradford reveal synergistic thinking.

To do this, Franklin built a multimedia empire over time. He combined the ownership of multiple printing presses in various regions with also creating and owning products.

On top of owning the presses that printed his own catalogs, magazines, almanacs and newspapers, Franklin also wrote content for them.

From there he conquered distribution, meaning that he could profit by taking care of mailing his own products.

These strategies compounded the value of the habits he used to accomplish and maintain all of these processes.

As you work on your own development as a polymath consider the many areas where you can build new skills on top of the foundational abilities you’ve already developed.

In the terms Peter Burke offers in his book, The Polymath, Franklin was a centripetal polymath. This means that he built his many skills to support a singular vision.

Other polymaths might stack on skills more randomly. There’s nothing wrong with doing this, but you’ll wind up missing the benefits of syncing your habits synergistically the way Franklin did.

What We Can Learn From Franklin’s Daily ScheduleThere’s no mystery to how Franklin fit all of his skills development and maintenance activities into his day. He lays out the process in his autobiography.

If you look at his illustration above, you’ll see an early version of what we now call “time boxing.”

But more important than giving his time organization habits a name, not that he did not cram. He crafted space for asking questions, removing clutter and thinking reflectively.

When you design your day around thinking, you’ll live more deliberately.

Your mind will have more space for focusing on what you want to learn. And your mind will be freer to integrate what you’re learning.

To emulate Franklin’s process:

Begin and end each day with one reflective thoughtProtect and assign your thinking timePlan and track your exact behaviors, not just what you accomplishIn other words, manage the meaning of your time. This will help align your activities into habits worth having.

Franklin’s Greatest Achievements as a PolymathEveryone will have their own favorite accomplishment from Franklin’s incredible life.

Here are the ones that stand out most to me.

Science and InnovationFranklin’s most famous experiment proved that lightning was electricity.

But he didn’t rely on intuition. He studied the topic deeply, including different ways to test his hypothesis safely.

He used some of the habits we’ve discussed above to contact other inventors and scientific-minded people.

As a result, he:

Invented the lightning rod, preventing destructive fires.Created bifocal lenses, solving a personal problem that still helps people around the world.Charted the Gulf Stream, helping massively improve Atlantic navigation.Franklin went beyond curiosity and the relentless consumption of information we see today.

He tested what he learned, applied it and shared his results, inspiring many other “citizen scientists” to do the same.

Politics and DiplomacyAs a student of classical philosophy, Franklin understood the political theories of his time incredibly well.

His self-directed reading habits included international law so that he could practice the highest level of public service.

As a result, he helped:

Draft the Declaration of Independence.Negotiate the Treaty of Paris.Serve as a cultural and political ambassador between America and Europe.Although some people attribute Franklin’s success to charisma, that’s not the full story.

He studied people carefully in addition to being a practitioner of rhetorical tools of persuasion. He turned everything he learned into skills that he leveraged.

Philanthropy and Civic InitiativesFranklin used his knowledge and business acumen to serve others.

The list of examples is long, but includes:

Founding lending libraries.Establishing volunteer fire departments.Organizing street cleaning and mutual aid groups.All of these came from Franklin’s passion for people.

But their success was aided by the habits that structured his interdisciplinary study efforts.

Writing and PublishingAs a writer and publisher myself, Franklin has inspired me for years.

Everything from his habit of reconstructing what he’d read from memory to building a multimedia conglomerate has given me insight into how to enjoy success of my own.

Franklin’s lifelong writing habits led him to:

Create Poor Richard’s Almanack, where he shared his practical wisdom and philosophy.Establish a lucrative career in printing, publishing and distribution.Tackle politics through satire by writing dozens of pseudonymous essaysStacked, Not ScatteredIf there’s one major lesson to take from Benjamin Franklin’s learning life, it’s that he leveraged the power of structure and balance.

His achievements were the product of interleaving:

CuriosityStudySystems developmentExperimentationAnalysisSharingIt was like a perfect circle.

And one that anyone can emulate.

But if you find that your mind is scattered, I suggest getting some memory training.

That might sound like a leap in logic, but if you’ve enjoyed the insights about Franklin you’ve read today, I have good reason to believe that Franklin’s memory was sharp.

It’s part of the explanation for why he could pay attention to what mattered and prioritize the right habit stacks at the right times.

To help you get your memory sharper so you have more focus and clarity, consider signing up for my free course.

Its exercises will help you improve your working memory so you can process more ideas faster.

And prioritize them like Franklin.

So what do you say?

As far as I can tell, Franklin wasn’t born a polymath.

Nor did he wait to be taught.

He used daily discipline, deadlines, intentional habits and a relentless drive to help others enjoy an incredible life of learning.

His polymathy was forged.

And that means you can forge your own polymathy too.

Start with one habit, one question and one page in a journal.

And keep going. Before you know it, learning multiple skills and fields of knowledge will fill your entire being with accomplishment and joy.

July 29, 2025

How to Memorize a List Quickly (And Maintain It Forever)

To make learning how to memorize a list quickly a fast and seamless process, I suggest you learn to use the Memory Palace technique.

To make learning how to memorize a list quickly a fast and seamless process, I suggest you learn to use the Memory Palace technique.

That’s because I believe memorizing a list should not be hard.

And people who struggle with with them?

It’s not because their memory is bad.

They’re often just using the wrong method.

I’ve been thinking about lists a lot lately as I reach the final stages of establishing a real-world Memory Palace with a bookshop in it.

To pull it off, I’m studying real estate in a course.

It involves all kinds of acronyms, form numbers and logistics.

And thanks to the technique you’re about to discover, I’m retaining the lists of information with easy.

The Memory Palace technique is not a trick.

It’s a system.

And once you learn it, you can memorize any list. Quickly and for life.

Let’s begin.

How to Memorize a List FastThere’s a fair amount of confusion about list memorization because there are different ways of doing it.

So many ways that people wind up confused and wondering which approach to use.

For example, you might have heard of Harry Lorayne.

He was a magician who popularized using mnemonics for remembering lists using the pegword method.

But what if you want to memorize a list of numbers, like Akira Haraguchi who was able to commit 100,000 digits of pi to memory?

What if you’re a medical professional who needs to memorize lists of symptoms, pharmaceutical information and all the carpal bones?

Or perhaps you want to memorize vocabulary as part of learning a language.

Perhaps your goal is even more modest. You just want to remember a to-do list or the groceries you need to pick up from the store later.

For each of these goals, I suggest you sidestep most memory techniques and get started immediately with the Memory Palace technique.

I teach all of the other techniques in the video above, including number rhymes.

But since I don’t recommend those techniques as the fastest and most practical means of memorizing a list, let’s get into the technique I favor the most.

In detail.

Step One: Create Your First Memory PalaceA Memory Palace is a form of mental association where you place a list of information along a journey you assign within a familiar location.

You’ve probably seen the technique used in Sherlock Holmes when the iconic character says, “I must go to my Mind Palace.”

In case you’re not familiar with this mnemonic device, this ancient memory technique has been used for centuries.

Essentially, you just mentally order locations in the manner you see in this image:

And if you were Sherlock and had to commit a list of facts about a case to memory, you would use a location like the study pictured above.

To avoid laying out associations chaotically, you would identify a few places (called loci) where you can “store” each part of your list.

For example, if you needed to of a suspect, you would place a mnemonic image on the chair labeled “1” in the illustration above. You do that by using a very special form of association, which we’ll discuss next.

Step Two: Pair Each Item on the List with an Association & the Memory PalaceLet’s use the example of memorizing a grocery list.

To do this, mnemonists (people who use memory techniques) use what are called mnemonic images.

If carrot is the first item on your list, you just imagine a giant carrot on the chair in your office.

That’s weird and strange enough to stick in your memory.

But what if you have a list of facts or the names of the presidents? This kind of information needs to be transformed mentally into an association that’s a bit more elaborate.

For example, if the first name is Washington, you can imagine a washing machine on your bed. Imagine yourself commenting that it weighs a ton. Washing machine + ton = Washington.

How to Practice Placing a List Item in a Memory PalaceFor practice, write out your to-do list on a piece of paper.

Let’s say you have to attend a meeting about a technology at 2 a.m. The topic is Microsoft’s Zune.

To add an association and place the word in your Memory Palace, you will need to split the word using the principle of word division I teach in my bestselling course, How to Learn and Memorize the Vocabulary of Any Language.

For this word, I would personally imagine my favorite zoo in Berlin and have the movie Dune playing while zebras watch.

Zoo + Dune = Zune.

What about the time of this meeting, 2 p.m.?

To add this kind of information to your to-list, you’ll want to use either the Major System or a PAO System.

Although these memory techniques are somewhat advanced, anyone can learn them.

Step Three: Gather the Information Into the Best Possible OrderSometimes the order of items is clear.

However, when studying for an exam, you might need to rearrange the main points in different orders of importance.

For this reason, I like to extract information from textbooks onto flashcards. That way I can easily move the facts around and place them in the most logical order before creating associations and placing them in one of my Memory Palaces.

As a pro tip, here’s something you can try:

I normally draw my Memory Palaces out on a piece of paper (these drawings serve as essentially a list of already-remembered stations within a location).

Then I fold the paper around the flashcards. The example you see above is one of the Memory Palaces I used when I learned Mandarin and passed Level III. Here’s what some of my cards looked like:

If you like the idea of being able to keep the lists of information you need to remember flexible, I also use special flashcard methods known as Zettelkasten and the Leitner System.

Step Four: Use Optimized Spaced Repetition For Reviewing Your ListHere’s where the Memory Palace technique for memorizing lists really shines.

Not only does the technique let you include as many items as you like.

It also makes it easy to use what scientists call spaced repetition. If you’re using flashcards as I discussed above, this kind of rehearsal technique looks like this:

The Leitner spaced repetition system helps you manage your exposure by placing accurate and inaccurate flashcards in boxes.

The Leitner spaced repetition system helps you manage your exposure by placing accurate and inaccurate flashcards in boxes.If you’re using the Memory Palace approach (which is kind of like using chairs and other furniture as index cards you draw on), here’s the process:

You simply mentally revisit the journey in your Memory Palace.

Then, on each station, you recall what funny image or direct association you put down.

Try it now:

If I ask you to think about the list item we discussed on the chair in the Sherlock Mind Palace example above, you will probably remember that we talked about a giant carrot.

That one came easily.

But what about the item you needed to discuss at a technology meeting?

Although it may take a second, provided that you personalized your own mnemonic associations, you should be able to get back the word “Zune.”

And that’s another key:

As the Renaissance memory master Robert Fludd used to stress about using these memory techniques, you need to personalize them so that when you are reviewing the images associated with the list items, they pop much better. He was completely right and contemporary science has shown this to be true.

The principle of personalizing your images belongs to what scientists call active recall. By adding personal elements to the information on your lists while you link them with associations, you increase your chance of remembering them.

Many people learn this technique within minutes and immediately get it working.

Memorizing Lists FAQOver my years of teaching the Magnetic Memory Method, people have sent me many questions about dealing with lists.

For example, one of my students in the Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass emailed today about memorizing the Buddhist eightfold path.

He expressed some concerns that naturally come up when dealing with lists where each item involves multiple words.

We’ll get into these issues and more in the following list of questions and answers.

What’s the fastest way to memorize a list of words?The brief answer is to become a mnemonist who uses Memory Palaces and related tools.

That way, you’ll have all five of the main mnemonic systems needed for rapidly recalling information in list format.

The longer answer is that you need to start where you’re at.

Learn the memory skills I teach, and then set benchmarks.

If you start by memorizing just 2-3 items and practice recalling them reliably, move on to 4-5 items.

Progressively build the amounts from there by setting time challenges for yourself. If you can memorize 10 items in one minute, challenge yourself to build up to 15, then 20.

If you really want to push your skills, you can explore making your Memory Palaces “stickier” by pre-loading them with associations from your PAO System.

This is how some memory athletes have improved their speed with the kinds of lists that come up in memory competitions.

How can I memorize a long list without fogetting an item in the middle?To establish long-term retention and recall of each item, you need to use spaced repetition.

You can use Memory Palaces, flashcards, Leitner boxes or software to help.

But giving equal doses of primacy effect and recency effect to each item in the list is key.

How do I memorize a list in order vs. out of order?Although this is an interesting question, I’m not sure what it means.

Everything we do occurs in time. So if you’re memorizing a list, time always sets some kind of order, i.e. the first thing you memorize is followed by the second.

It’s possible that when people ask this question, they are trying to work out how they can add something to a list they’ve memorized after the fact.

There are two ways:

Use the principle of compounding as taught in the Magnetic Memory Method MasterclassAdd new details to a completely new Memory PalaceI do both, and it depends on the context.

In the case of the student who asked me today about memorizing the items on the Buddhist eight fold path, it actually makes sense to memorize it in two passes within a single Memory Palace.

First, you set the keywords up and use spaced repetition to establish long-term recall. Then you add the description of each step on the path.

How do actors memorize lists of lines or cues?It’s important to realize that different actors approach learning their lines in different ways.

For those using memory techniques to memorize lines, I suggest this full tutorial. It describes the approach I use for memorizing Shakespeare and recommends a book you might like to read.

You might also have the option of not memorizing your lines at all.

In Dustin Hoffman Teaches Acting, Hoffman relates a story where he saw Robert De Niro reading lines from index cards he kept in his pockets shortly before the director would call action.

According to Hoffman, De Niro said that he didn’t memorize his lines because he didn’t want to look like he was carrying around his responses for two weeks. By not memorizing his lines, he made his performances more authentic.

Of course, the ultimate answer is to ask what your director wants and be prepared to collaborate with them. That way, you’re much more likely to produce an incredible stage play, series or film.

For more on the relationship between memory and acting, please see 8 Unusual Memory Tips from Actors Who Don’t Clown Around.

How do students memorize lists for exams (like biology terms of historical details)?Unfortunately, many students cram.

But the best students do what we discussed today. Or they might pursue a study strategy that involves linking without using a Memory Palace.

The important thing to understand is that the exact nature of the information is not that important when it comes to using memory techniques.

So long as you’re prepared with the techniques, you can learn anything that involves numbers, words, concepts or symbols.

For examples, you can see my tutorial on memorizing historical dates and medical terminology training post.

What’s the best way to memorize vocabulary lists in a foreign language?Technically, the best way to study vocabulary lists is to find a method that you’ll actually use.

If using rote repetition helps you achieve your goals, that’s a great way to go about learning a language. In this tutorial about rote learning, I suggest reasons why it’s not the best idea for many people.

But that doesn’t mean it won’t work for you.

Beyond that, I would suggest that memorizing lists is just part of learning a new language.

You also need to add reading, writing, speaking, listening and reading.

Combined with memorization, I call this approach The Big Five, and this illustration shows how these activities work together:

This process is very effective because it gives you natural spaced repetition and lets you experience the words on your vocabulary list in context.

How to memory champions memorize decks of cards or digits of pi? Are lists different?This is a great question because although committing a sequence of digits is a list, it can feel different.

This is because many mnemonists memorize pi from left to right in their Memory Palaces.

Likewise, many memory athletes memorize cards by following horizontal lines along their memory journeys.

When I memorize cards using the strategy I teach in this card memory tutorial, however, I often place cards in vertical rows.

Using a chunking memory strategy, I usually memorize the cards in clusters of two or three at a time. This makes the task much faster.

However, just because the cards are memorized using different spatial configurations, the information is still essentially a list.

How many items can the average adult reliably retain without using memory aids?The answer will differ depending on the state of your working memory.

Most people can memorize 5-8 items if they are simple, like numbers.

But we’ve all had the experience of memorizing words and forget a bunch of them, even though they seemed simple.

This is why I personally commit to applying memory techniques to just about everything.

Today in my real estate class, for example, I quickly attached images to various numbered forms to start the process of committing them to memory.

And with memory techniques, there will be no end to the exact amount that any person can memorize, except lifespan.

People who attend my live workshops are constantly amazed by how much information I recite during my courses.

And the way I do it is simply described. I just memory techniques.

How much time should I budged for spaced repetition reviews?The exact amount depends on:

The volume of informationThe typeYour current level of skill with memory techniquesRather than consider time in the beginning, think about building your skills.

Then, once you’re able to reliably memorize lists, work on shaving off the amount of time you need by practicing so you get better.

Does writing a list by hand improve recall compared with typing it?Yes, and this Scientific American article gets into the scientific reasons why this is the case.

Also, I mentioned active recall above and the importance of personalization.

A second aspect of active recall involves writing.

The specific process is that you:

Bring the information in your list to mind by visiting the location you established in your memory palaceWrite it down on paperCheck your accuracyI’ve been doing a lot of this kind of active recall in my real estate course. The teacher and the program designers are very wise for including a lot of writing exercises.

How do I blend chunking, the method of loci and spaced repetition for maximum retention?One way is to use the Magnetic Memory Method, which I designed precisely to form that blend of rapid learning strategies.

Once you have the techniques in operation, all you have to do is organize your time.

If you’d like to discover more about what this approach is like, please register for my free course now right here:

It will help you create multiple Memory Palaces, discover fun and easy ways to use the method of association and more about how to rapidly apply spaced repetition.

Combined, you’ll soon have all the lists you want stored in long-term memory.

So what do you say?

Are you ready to give this approach to memorizing lists a try?

Make it happen!

July 21, 2025

Master the Major System and Memorize Any Number Fast

The Major System is a centuries-old mnemonic tool that helps you transform numbers into concrete words and striking mental associations to increase their memorability.

The Major System is a centuries-old mnemonic tool that helps you transform numbers into concrete words and striking mental associations to increase their memorability.

You then apply these evocative mnemonic images to help with recalling the important numbers in your life. Such as:

Phone numbersPIN numbersAccount numbersBirthdaysMath formulasHistorical datesThe digits of piPlaying cards during gamesTechnically, the Major System is a phonetic peg system. It works either on its own or in combination with other mnemonic peg systems.

It looks like this, a simple pairing of 0-9 with a specific set of consonants:

The Major System

The Major SystemLike other mnemonic devices, this means that the Major uses consonant sounds to ‘peg’ numbers to words and images, making them easier to store and retrieve from memory.

Although people have been using the Major System (sometimes called the Major Method) to commit numbers to memory for centuries, there’s a rarely taught, but incredibly powerful dimension you’re about to discover.

I call it “bi-directionality.”

It’s the very approach to the Major System that helped me get my PhD in Humanities at York University. I memorized key historical dates, facts related to the history of science, logical formulas and more.

I’ve also applied the bi-directional Major System to learning several languages. I even used it in 2015 to take second place in a memory competition against a two-time Guinness World Record holder for playing cards.

On this page, I’ll share exactly how to use this mnemonic system yourself for memorizing any number. And I’ll share use cases for how you can get started using the Major System to absorb many other types of information.

Ready to get started applying this system to everything from banking numbers to complex academic material?

Let’s dive in!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vonJW...

What Is The Major System?The mnemonic Major System dates back more than 2000 years. The earliest version I’ve found is called the katapayadi. You can also find information about the ancient Hebrew version in Eran Katz’s Where Did Noah Park the Ark?

These versions show that people across many cultures have turned to this kind of mnemonic device throughout time.

In our era, it used for everything from credit card numbers and phone numbers to thousands of digits of pi.

Extraordinary as that sounds, Akira Haraguchi famously used the Japanese version of the Major System to recite over 100,000 digits of pi from memory.

A Brief History of the Major SystemHistorically, we know from Hugh of St. Victor that students of the Bible used a similar system to memorize the dates of Adam and his descendants.

Hugh even linked numbers to people, actions and objects back in the twelfth century in The Three Best Memory Aids for Learning History. You can find an English version of this text in The Medieval Craft of Memory.

Although Hugh was already quite sophisticated, the Major System really start to take shape in the 16th and 17th centuries through people like Giordano Bruno and Robert Fludd.

Both of these Renaissance memory masters used letters and consonants to represent numbers, but their systems were often inconsistent and lacked a standardized approach. Nonetheless, their contributions added new dimensions, such as Bruno’s influence on the development of the Memory Wheel, and Fludd’s evolution of the number-shape system of Jacobus Publicius.

When it comes to developing the standardized system we now use, these are the most important figures.

Johann Justus WinckelmannJohann Justus Winckelmann was a German mathematician and mnemonist. He proposed a method where each digit was always associated with the same specific consonants, laying the groundwork for later developments.

Aimé ParisAs a French mathematician and memory expert, Aimé Paris simplified the associations, making the system more user-friendly. His version is nearly identical to the Major System as we know it today.

Major Beniowski and the Naming of the SystemThe Major System is named after Major Beniowski, the 19th-century linguist, memory expert and author of the strangely titled, The Anti-Absurd or Phrenotypic English Pronouncing and Orthographical Dictionary.

Here’s how he graphically represented the Major System in his book by embedding the consonants into each of the digits, 0-9:

Apart from his book, not much is known about Beniowski. Some people believe that “Major” refers to Beniowski’s military rank.

Although that’s the most likely explanation, the name clearly underscores Beniowski’s “major” role in popularizing and standardizing this mnemonic method. Through his teachings and writings, Beniowski helped spread the use of the system, making it accessible to a wider audience.

The name is also much easier to remember than “alpha-numeric” code.

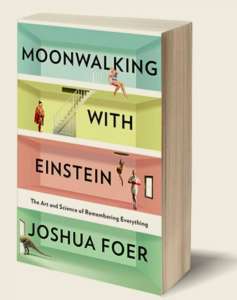

The Major System continues to evolve and gain popularity. Memory experts like Harry Lorayne brought it to the masses. Later books like Moonwalking with Einstein encouraged many people to incorporate the system into their learning lives.

The technique continues to evolve to this day. Many memory competitors now use a variation called the Shadow, which is still based on the same alpha-numeric code you learned earlier in the video above.

If you want to check out some of the most impressive users of the Major, check out my podcast episodes with Katie Kermode and Don Michael Vickers. These memory athletes are seriously impressive.

They’re hardly the first of my memory champion friends to use the method, however.

Using Tony Buzan‘s SEM3 technique, many early memory competitors also used it to win year after year. The Major is still at the core of newer techniques like the Shadow, which competitors like Alex Mullen and Braden Adams have used to stunning effect.

Competition is not something many of us are interested in, however.

And the fact is that the Major System was never just about numbers. Limiting the Major in that ways is one of the biggest limitations learners impose on themselves.

But before we dive into how to use it bi-directionally—for both numbers and deep conceptual memory, let’s make sure you have the fundamentals locked in.

How the Major System Works in EnglishNow that you know where the Major System comes from, let’s break down exactly how it works. We’ll start by learning the sound-to-number code that makes it so powerful.

You start by converting the digits 0-9 into consonant sounds. This is basically a form of mnemonic chunking, a memory strategy that makes information easier to recall by breaking it down into smaller units.

The smaller these units are, the easier it is to make simple words that can be attached to meaningful associations you won’t forget.

Here’s a table of the core phonetic code used in the English version of the Major System. As you can see, each digit is linked to one or more consonant sounds, which you will eventually use to form words.

As you go through this table, you’ll notice that I’ve added a few suggestions for how to commit these pairings to memory:

0 → S or Z (sounds like the “s” in “zero”)1 → T or D (sounds like the “t” or “d” in “toad”)2 → N (has two downstrokes, resembles the letter “n”)3 → M (has three downstrokes, resembles the letter “m” or a moustache on its side)4 → R (the word “four” has four letters and ends in “r”)5 → L (hold your whole hand with the thumb out and the hand makes the “L” shape)6 → J, Sh, Ch, or Soft G (a cursive “j” has a similar shape to “6”)7 → K, G (hard), C (hard), or Q (a “k” can be seen as two mirrored 7s)8 → F or V (cursive “f” and “8” look similar)9 → P or B (both have a loop resembling “9What About Vowels?Most people leave all vowels out of the system (A, E, I, O, U) .

That’s because vowels are used to form meaningful words or phrases by inserting them between the consonants.

For example, if you need to memorize 84, you can transform F and R into words like fire and fur. I’ll share a few more examples below to help you get the gist of how vowels work in combination with the consonants.

The Major System in Other LanguagesSimon Luisi, a French-Canadian mnemonist and organizer of the Canadian Memory Championship event, uses a variation where 3 is also paired with W and 7 with Y.

To help people expand their Major System, Simon joined me on the Magnetic Memory Method Podcast to discuss his approach in this episode:

In addition to Simon’s variations, you’ll find different versions in many languages.

Languages like Spanish and Russian each adapt the Major System’s consonant assignments to help native speakers of these languages assign the maximum number of words.

Here’s an illustration showing how the Major System looks in Russian. Notice how the logic and its foundations remain, even if the exact consonants change:

In German, the Major System remains identical to English.

However, authors like Ulrich Voigt use the term “Zifferncode.” That’s the term he uses in his excellent book, Esels Welt: Mnemotechnik Zwischen Simonides und Harry Lorayne.

“Ziffern” means digit, and assembling digits into a code of meaning is exactly what you’ll be doing. No matter what language you speak, let’s next explore how to use these digit-sound pairings to make words and expand them into unforgettable mnemonic associations.

How to Turn Numbers Into Vivid Associations with the Major SystemThe next step is to transform sequences of numbers into vivid mental images.

To remember the number 123, you could break it down like this:

1 → T or D2 → N3 → MFrom this arrangement, you might form the word “Denim” (D-N-M). This word is reached by inserting vowels between the consonants linked to the digits.

As you can see, D-N-M isn’t any more meaningful than 123. But once you insert the vowels to make a word, it’s easy to imagine denim. You can add even more meaning by imagining someone famous wearing denim whose name sounds similar, like James Dean.

Let’s take another example:

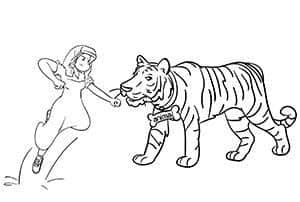

If you had to memorize 22, you could insert the vowel U and imagine a nun. If you had a number like 22235, you could imagine a nun attacking an “animal” like a tiger just by adding more vowels to the sequence to form words.

At this point, you’ve gone beyond mere words. You have the basis for building a narrative, which in the world of mnemonics is called the story method.

Back to the AncientsI mentioned adding James Dean to make “denim” for 123 much more memorable.

This suggestion is based on an idea from Hugh of St. Victor, whom I mentioned above.

Don’t worry if you don’t know many celebrities.

You can also draw upon people from you real life, such as:

FriendsFamilyProfessionals (lawyers, teachers, doctors, dentists)PastorsAuthorsMusiciansHistorical figuresSince Hugh’s time, many people have used this more elaborate approach. It is now called a Person Action Object System or PAO System.

You can read my full PAO System tutorial when you’re done learning the Major.

PAO is the system I wish I had been using when I competed against Dave Farrow, the Guinness World Record holder I told you about in the introduction.

But don’t worry if you’re not ready for it yet. Like I said, I still came in second place with just the Major. You can read the full story of that competition here for more detail.

Now let’s take the vivid associations you’ve learned to form and give them a place to call home.

How to Use the Major System in a Memory PalaceThe Memory Palace technique is one of the most powerful ways to situate the associations you’ve assigned in long-term memory. It involves selecting a familiar location and identifying a simple path for you to place figures like tiger-fighting nuns and James Dean wearing jeans.

I’m talking about locations like you:

HomeSchoolChurchFavorite cafes, restaurants, movie theatresLibrariesBookshopsParksThe key is to develop clear mental journeys through your Memory Palaces.

They should be truly based on what is in your memory and have little or no imaginary elements (at least not in the beginning). That way your focus can fall on encoding the number-consonant associations into these spaces.

Once you’re set up, convert the numbers you need to memorize into consonants. Then form words or phrases by adding vowels or other non-consonant sounds. These words should be vivid and memorable and follow the principles you can learn by using these visualization exercises.

Next, place the words you come up with in a Memory Palace. Basically, you’re associating each word as a mnemonic image with the location.

Make each one as vivid as possible, with lots of detailed and interactivity.

Here are some examples:

Example 1: 3143 → M

1 → T or D

4 → R

Word: “Meter”

Memory Palace Placement: Imagine a large meter on the wall of your bedroom.

Example 2: 727 → K or G

2 → N

Word: “Gun”

Memory Palace Placement: Picture a gunman standing in the kitchen, guarding the fridge.

By placing these images in specific locations within your Memory Palace, you can mentally walk through the space and easily recall the numbers associated with each image.

How to Get Numbers Into Long Term MemoryThis next step is very important.

Although you will increase your ability to memorize this information greatly by not only creating a crazy image and sticking it in a Memory Palace, you can and should lock it down for the long haul.

You do this by revisiting the imagery several times. I suggest you specifically use a process called spaced repetition.

It’s really easy. You’ve created a Memory Palace and you know exactly where to look for that tiger-attacking nun 22235.

And if you’ve got ten pieces of information along that journey, it’s easy to travel it and decode each image. It’s almost like watching a movie.

I recommend that you revisit that journey and watch that movie you’ve created (making sure to decode the imagery and practice retrieving the information) at least 5 times the first day. This suggestion is based on remarks by Dominic O’Brien who created an alternative number mnemonic system called The Dominic System.

What To Do If You Have An Exam Coming UpIf you’re studying for an exam that involves historical dates or formulas, I’d recall the numbers five times a day for a week and then at least 1-2 times a week thereafter. Do this for as long as you want to keep the imagery fresh and available.

It will probably still be there if you don’t perform this Magnetic Memory Method Recall Rehearsal, but you might have to fish around for it.

But if you’re serious about being able to recall the information, you’ll revisit it more than a few times to get it down cold.

That’s just how the method of loci works best. Every good Memory Palace book stresses the same point.

And the best part is that you’ve done so without having to use index cards or any weird and boring stuff like that.

The only time that it’s good to repeat information over and over again is when you’re using your imagination to do it. That makes both your memory and your imaginative abilities stronger and stronger.

Intermediate & Advanced Major System Techniques For Memorizing NumbersOnce you have the basics of the Major Method down, you might want to learn how to create a Person Action Object (PAO) or 00-99 system. For that, please check out The 3 Most Powerful Techniques For Memorizing Numbers.

These next-level techniques for memorizing numbers will then help you in other areas, such as human anatomy. Learning numbers related to blood flow through the heart, for example, are easier and faster to absorb when using the Major System.

You can also think about using a Major System to help you memorize any book. All you need to do is call upon words or images for each page based on the page number.

For example, if you want to memorize a fact on page 75 of a book, you use an image built from the Major System to remember the location in the book. Then you use the page as the Memory Palace.

I did exactly this when I wanted to recall a point about episodic memory in Maps of Meaning. I turned 75 into John Cale and had him interacting with Freud and Shakespeare, who are related to memory science related to how we remember ancient wisdom.

You can also easily use the Major System in combination with a Memory Palace for language learning. I normally use alphabetical associations, but when I can’t think of images for some words, I just think through the consonants as numbers in the Major System and then start using that image.

Even if it’s not perfect or doesn’t exactly reflect pronunciation, it’s at least a starting point.

As a recent example, I did this with a Sanskrit phrase.

Although I later realized that a celebrity I’m aware of was better than my image for 07 (Oliver Sacks), at least working with Sacks to get started with “suktikarajatam” led me to think about using Sook-Yin Lee.

For more on just how deep into history this numerical bi-directionality goes, see my video tutoris called Aristotle’s Nuclear Alphabet and The Imaginary Memory Palace Method of Hugh of St. Victor.

And just to make sure you fully understand how valuable bi-directionality goes, let’s dig deeper into this powerful dimension of the technique.

Bi-Directionality Case Study:The Hidden Superpower of the Major System

Although it’s perfectly valid to use the Major System only for memorizing numbers like PINs, historical dates and long sequences of digits, you now know there’s more to the technique than that.

As artificial intelligence ramps up, I find myself using it much more often than ever before.

Take Lindy’s Law, for example, a principle which states that the longer something exists, the more likely it will continue to exist.

To lock in that idea using the Major System, I used the number 51 because of the strong L and D in “Lindy.”

Here’s a quick YouTube short to enhance the written explanation that follows:

https://youtube.com/shorts/Tqm2HmzCqr...

As you can see, I turned L and D into a name more familiar to me than Lindy: Alan Ladd. (L = 5 and D = 1).

I then imagined Alan Ladd pouring a “latte” (also 51) over a copy of Shane, his most-known film. Since this movie has endured for generations, it’s very likely it will continue to enjoy fame.

This is the power of using the Major System in a bi-directional way.

Rather than limiting yourself to using the Major System for numbers, you’re using it to encode words and concepts using the same system.

You’ve now doubled its value, if not more as you start using it to mentally catalog entire books, vocabulary lists and more with greater speed and accuracy.

Major System FAQAs you’ve seen, the Major System is a powerful mnemonic technique that converts numbers into consonants.

By inserting vowels, you can create simple words that can be expanded into vibrant images and stories.

Let’s turn now to some of the questions I’ve received about it over the years with some answers that will help expand what you’ve just learned.

Why should I use the Major System?Numbers are abstract and difficult to remember.

But by turning digits into images and stories, your brain remembers them.

As you’ve seen, you can also use the Major System bi-directionally. Whenever you struggle to find an association for a word or concept using the alphabetical pegword method, you can look at the numbers associated with the consonants. Then use those images.

Personally, I wish I would have started using the bi-directional approach much sooner.

Is the Major still worth learning in the age of AI?Absolutely yes.

As you saw in the YouTube short above, I recently used it to memorize an important concept in computer science.

So if anything, it’s even more valuable now than in any other period of history.

Remember, the value of thinking in relationships, associations and patterns is beyond measure. You differentiate yourself by mastering this mnemonic system.

What’s the difference between the Major System and the Dominic System?The Dominic System assigns numbers to people specifically using their initials.

For example, 1 = Andre the Giant, 2 = Bugs Bunny, 3 = Cheshire Cat.

Although the Dominic System is just as structured in its way, there’s a higher level of arbitrariness. You have to work harder to make the link between the associations.

The Major is much more flexible and less arbitrary. There’s a reason why you use the pope for 99 (because 9 is associated with B or P). You’re getting more value because of how easy it is to make words and logically infer why you chose them.

What about the Shadow System?Although based on the Major, I believe the Shadow is specifically for memory competition.

In my understanding, it evolved for card memorization because competitors want to memorize multiple decks at a time. This means you will get two Jack of Hearts in row (if not more).

It’s definitely worth looking into, but I stopped learning it when I realized I would never use it.

What if I forget which vowel I inserted between the consonants?This might happen in the beginning.

But as you establish a standard set of words for all of the 2-digit pairs, you’ll use the same associations repeatedly.

When I drilled mine to memory the first time, I put all the numbers from 00-99 on index cards. I then practiced shuffling them and naming my chosen figures.

Once I could name them all within seconds, I started practicing memorizing strings of digits.

By the time I had realized that the Major could be used bi-directionally, I was able to easily apply the same images to vocabulary and phrases.

How can I practice applying the Major System for real world benefit?There are a number of valuable ways to practice applying the Major System once you’ve learned it. You can:

Take memory number tests frequently.Keep a journal as suggested by accomplished memory athlete Johannes Mallow.Put numbers on flashcards and test yourself manually.Use the International Association of Memory’s free software for generating random numbers.Attach the Major System to a pack of playing cards and memorize their order.Study vocabulary by using the bi-directional method.How often should I practice?It’s really up to you and your needs.

But as I discuss in my book on how to memorize numbers, math and equations, I usually practice 3-4 times a week, typically by using the final method: playing cards.

But all of the above methods are a lot of fun and I use the technique as I read often as a kind of “Magnetic Bookmark.”

Rather than putting a print bookmark into my books, I glance at the page number and have my association interact with the information on the page. That makes it easy to remember where I was in the book.

Can I use the Major System for memorizing formulas?Yes, and the technique applies to formulas in multiple areas, from chemistry to physics, biology to computer science and programming. You can also apply the Major to speed math and becoming a mental calculator.

Here’s a video where I break down how to do exactly that:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uAkiu...

The trick is always to make sure that you are prepared with the additional symbol and alphabet systems I describe in the video above.

To give you a quick example:

When I was learning the formulas used in logic, I imagined a totem pole for totality and an air conditioner blowing cold air on one of the Ninja Turtle’s weapons for condition. These are examples of the pegword method applied to visual symbols.

For even more advanced techniques related to numbers and equations with examples, please go through my detailed tutorial on how to memorize a textbook.

What’s the role of chunking in the Major System?The reason systems like the Major work so well is that they help you break long strings of information down into manageable units.

People who memorize large amounts of pi aren’t really memorizing dozens of digits at a time. They are memorizing how interesting images interact in their Memory Palaces.

By recalling these compelling scenarios, they “translate” them back into the original digits.

Should I apply the Magnetic Memory Method technique of KAVE COGS to the Major System?Yes. Doing so will make your associations even stickier in your Memory Palaces.

In case you’re new to KAVE COGS, it is an acronym to help you remember to add the following multi-sensory associations:

KinestheticAuditoryVisualEmotionalConceptualOlfactoryGustatorySpatialWith “denim” for 123, you might feel what it’s like to be James Dean wearing denim and hear the zipper as you imagine looking at them.