Joyce Elson Moore's Blog

February 27, 2015

Always the Music

Always the Music is the story of Cosima, born in 1837 to the Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt and his mistress, Marie d’Agoult. Set against the backdrop of late 1800’s Paris, Cosima’s story tells of a tumultuous childhood and adolescence, followed by a notorious affair with one of Germany’s most famous composers. Her life is a tale of courage and determination in the face of obstacles.

Always the Music is the story of Cosima, born in 1837 to the Hungarian pianist and composer Franz Liszt and his mistress, Marie d’Agoult. Set against the backdrop of late 1800’s Paris, Cosima’s story tells of a tumultuous childhood and adolescence, followed by a notorious affair with one of Germany’s most famous composers. Her life is a tale of courage and determination in the face of obstacles.The Paris in which Cosima spent her formative years was not what visitors see today when they visit the famous City of Lights. From fashion and shopping, to dining and entertaining, nineteenth century Paris was a different world.

During the 1800’s, Parisian fashion went through many changes. In mid-century, the crinoline defined a lady’s figure. It spread the skirt of a dress equally around the body in a rounded shape. The crinoline, originally made of horsehair and cotton or linen thread, played an important role in women's fashion for decades. Later the word crinoline referred to any stiff petticoat or rigid skirt that supported women’s dresses and formed them into the rounded shape fashionable at the time.

After 1860, skirts in Parisian fashion began to narrow and flatten in front, with much of the bulk of fabric moved to the back. By the mid 1870’s a new undergarment, the tournure, had replaced the crinoline. The tournure supported the large backside of dresses, a style known as Cul de Paris, or ‘the Paris bottom'.

Shoppers in nineteenth century Paris enjoyed browsing perfume shops. In the latter years of the century, perfume production underwent a change. Perfume was no longer a luxury afforded only by the elite. Thanks to new innovations and techniques in production, it became widely available. Perfume emerged as a popular luxury, thanks to its new affordability and what some referred to as a ‘hygiene revolution'.

Those dining in Paris in the late 1800’s enjoyed fine culinary experiences. The terms gourmet and gastronome emerged at this time. It is widely believed that the birth of fine restaurants was caused by the French revolution. Seeking safety, aristocrats fled Paris, leaving behind their fine chefs and the contents of their wine cellars. These abandoned workers and fine bottles came together and over fifty new restaurants popped up around Paris.

Strolling the streets of late 1800's Paris was a treat to the senses as art, culture, fashion, and fine dining became commonplace. No wonder Cosima, forced to leave Paris during her adolescence, schemed to return to The City of Light.

Always the Music brings to readers the story of Cosima, a woman who rose above the shadow of three musical geniuses. This is another book in a series on Women in History. It is written under the penname, Elizabeth Elson.

Look for a giveaway next week where 15 readers will win a free copy of this exciting novel.

Published on February 27, 2015 15:52

April 8, 2012

Julia Augustii

Julia Augustii, daughter of the man who inherited his power from Julius Caesar, was born in 39 BC. As an infant, she was betrothed to Marc Anthony's eldest son, who was killed shortly after his father committed suicide. Her tumultuous life fascinated me enough to research her life and times more thoroughly, especially her relationship with Marc Anthony's son, Iullus. Julia's stepmother, Livia, is a fascinating woman, too, as are Julia's successive husbands, especially Agrippa, about whom books and movies have been written. Julia, Daughter of Rome, is my first ebook, and will be followed by other novels about women who lived their lives in the shadow of famous men.

Julia Augustii, daughter of the man who inherited his power from Julius Caesar, was born in 39 BC. As an infant, she was betrothed to Marc Anthony's eldest son, who was killed shortly after his father committed suicide. Her tumultuous life fascinated me enough to research her life and times more thoroughly, especially her relationship with Marc Anthony's son, Iullus. Julia's stepmother, Livia, is a fascinating woman, too, as are Julia's successive husbands, especially Agrippa, about whom books and movies have been written. Julia, Daughter of Rome, is my first ebook, and will be followed by other novels about women who lived their lives in the shadow of famous men.Because this was set in a much earlier period than my previous historical novels, I wrote it under the name Elizabeth Elson. I'd love to hear from my readers as to what they think of the book. For me, it was an exciting foray into a fascinating period in history.

Published on April 08, 2012 18:30

November 13, 2011

History of Coffee

Viennese coffee, made with hot foamed milk and sugarThe history of coffee can be traced back to at least the 13th century, but if may have been used for years before that. After the 16th century, Dutch traders brought coffee plants to Italy, and from there coffee's popularity spread through Europe and to the New World, aided by frequent trade between Venice and Muslim countries.

Viennese coffee, made with hot foamed milk and sugarThe history of coffee can be traced back to at least the 13th century, but if may have been used for years before that. After the 16th century, Dutch traders brought coffee plants to Italy, and from there coffee's popularity spread through Europe and to the New World, aided by frequent trade between Venice and Muslim countries.The English word coffee may have come, in various forms, from Kaffa in Ethiopia, where the plant originated.

Legend has it that a mystic saw some birds acting particularly lively, and experimented with the berries himself, but the first credible evidence of the coffee bean's use was in monasteries in Yemen, where the monks used it to keep them awake during evening devotions.

In 1720 traders brought coffee plants to islands in the Caribbean, where plantation owners quickly realized the plant's value, setting in motion the massive transport of slaves from Africa to Cuba to work the fields.

At various times, coffee has been forbidden, in Turkey and other places, but because of its popularity, the bans were always quickly overturned.

For myself, I'm just grateful to whomever the first man was who got past the bitter taste of the raw bean and experimented with making a tasty brew.

Published on November 13, 2011 08:42

October 2, 2011

Coffin Portraits

The protagonist in my current work-in-progress is from Warsaw, and in doing research about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, I ran across an article of interest. Coffin portraits, seldom used outside the Commonwealth, were an important part of Polish funerals, usually lavish and ceremonial, even for the common people. However, a farmer's portrait may have been drawn by a family member, whereas a nobleman's image was done by a professional artist. Portraits of the deceased were attached to the coffins, then removed before burial and hung on the walls of the church.

The protagonist in my current work-in-progress is from Warsaw, and in doing research about the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, I ran across an article of interest. Coffin portraits, seldom used outside the Commonwealth, were an important part of Polish funerals, usually lavish and ceremonial, even for the common people. However, a farmer's portrait may have been drawn by a family member, whereas a nobleman's image was done by a professional artist. Portraits of the deceased were attached to the coffins, then removed before burial and hung on the walls of the church.The metal on which the portrait was painted was shaped to fit the end of the coffin where the head of the deceased would be. The opposite end of the coffin generally held the epitaph, and on the side of the coffin mourners would see the coat-of-arms of the deceased. Because most were painted in oils, on either tin or silver, the images have disappeared from churches as years passed, either taken as booty during one of several wars, or stolen by vandals.

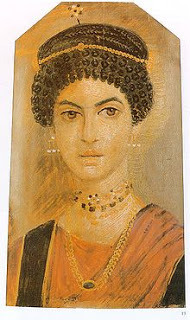

Aside from this period in the Polish Commonwealth, the term coffin portrait was also used to describe the funerary art from Ancient Egypt, portraits common during 1 BC and until 3 AD, a relatively narrow expanse of time. The Egyptian portraits were painted on wood. The portrait covered the face of the mummy, and was attached to the cloths used to wrap the mummy. Some nine hundred of these Egyptian portraits are in the hands of collectors and museums, but because of the warm climate in Egypt, which helps to preserve the wood, the portraits are useful in determining hairstyles and clothing of the period.

Aside from this period in the Polish Commonwealth, the term coffin portrait was also used to describe the funerary art from Ancient Egypt, portraits common during 1 BC and until 3 AD, a relatively narrow expanse of time. The Egyptian portraits were painted on wood. The portrait covered the face of the mummy, and was attached to the cloths used to wrap the mummy. Some nine hundred of these Egyptian portraits are in the hands of collectors and museums, but because of the warm climate in Egypt, which helps to preserve the wood, the portraits are useful in determining hairstyles and clothing of the period.

Published on October 02, 2011 13:04

September 25, 2011

Review of an Historical Mystery

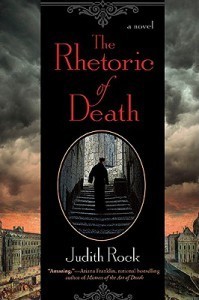

I loved mysteries as a teenager, but somewhere along the way, I turned to historical novels, my first love. However, not long ago I took the time to read a debut mystery written by another member of Historical Novel Society. I love books set in France (as is evident by my writing), and so I settled down to read Judith Rock's Rhetoric of Death, an historical mystery set in 17th century Paris. To my delight, the novel has all the appeal of good historical fiction—the ability to transport me to the past, to the streets of Paris, where a Jesuit monk follows leads down dusty back alleys to solve the mystery of a murdered student and the attempt on the life of another.

I loved mysteries as a teenager, but somewhere along the way, I turned to historical novels, my first love. However, not long ago I took the time to read a debut mystery written by another member of Historical Novel Society. I love books set in France (as is evident by my writing), and so I settled down to read Judith Rock's Rhetoric of Death, an historical mystery set in 17th century Paris. To my delight, the novel has all the appeal of good historical fiction—the ability to transport me to the past, to the streets of Paris, where a Jesuit monk follows leads down dusty back alleys to solve the mystery of a murdered student and the attempt on the life of another.If you love historical novels, you will love Rhetoric of Death . Judith has another mystery just out, The Eloquence of Death. The book titles would be off-putting were the author not so talented, the plots interesting, and the characters so real. I'm recommending it to both my book groups, and highly recommend Judith's books to anyone who wants a book they can't put down until the final page, wishing then the read was not yet finished.

Published on September 25, 2011 14:12

August 20, 2011

History of Keyboards

Clavichord 1659

As early as the 8th century, musical instruments have had keys, though the keyed instrument Emperor Constantine sent to King Pepin of France was probably nothing like the keyboard instruments of today.

In the early part of the 11th century, Guido of Arezzo, a Benedictine monk who is regarded to be the inventor of modern musical notation (the staff) and the ut-re-mi (do, re, mi name for tones) devised a way to attach a keyboard to a stringed instrument.

One of the earlier keyboard instruments was the clavichord, which at first had only twenty keys.

After the 15th century almost all the key-stringed instruments used the chromatic scale, as we find it in modern pianos. Keyboard size varied from instrument to instrument.

In the 18th century, a piano maker in Vienna built a concave-formed keyboard, convinced it would better serve the tendency of the human arm to move in a semicircle.

A piano maker in the 19th century designed a keyboard on which the semitones (our black keys) were the same color as the full tones, and were not raised. Thus, the keyboard we know today is the result of experimentation through the ages. As a pianist, I am grateful to have raised black keys and the full 88-key keyboard of today.For further reading go to www.pianoworld.com

Published on August 20, 2011 18:33

July 15, 2011

Are Conferences Worth the Price?

[image error]

HNS Reception - photo by Adelaida Lucena-Lower Recently I attended the Historical Novel Society's conference in San Diego, where I was a panelist with three other authors, all of whom have a stack of best-sellers to their credit. Flights cross-country, hotel room prices, and conference fees can add up pretty quickly, and people have asked me, are conferences really worth the price? My answer is an unequivocal yes. First, you know that anyone there has an interest in your genre, or at least, in books and what makes them great. Secondly, no matter where you are in your writing career, you can always find workshops that will give you fresh knowledge, and improve your writing. I attended a workshop on Writing Gay Characters, and took notes like crazy--even spoke with one of the panelists who said he would gladly look over some scenes I was not sure were right. Thirdly, of course, are the pitch sessions, where you can meet that editor or agent you've been wanting to talk to, face to face. Add to all these benefits the networking, one of the most enjoyable parts of the conference. At one meal, I sat next to an author who I later learned sang in a group that does medieval music. What a coincidence! She and I started talking, and she knew I had written The Tapestry Shop, my 2010 release about a trouvere, one of the wandering poet/musicians in northern France during the thirteenth century. After I returned home, she wrote me that she read my book on her return flight, plus she send me a nice review. At a reception one evening, I met the author Karleen Koen, whose recent release, Beyond Versailles, intrigued me with its title. I am about halfway through the novel and loving it, and I loved meeting Karleen, a talented and intriguing personality.Are conferences worth it? Of course, and in this changing industry, I believe writers' conferences are more important than ever, not only for the reasons I mentioned, but to keep track of what lies ahead on the horizon--for authors and publishers and agents. Right now I'm looking forward to the Colorado Gold conference in September, sponsored by Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers. Maybe I'll see some of you there.

Published on July 15, 2011 12:06

June 12, 2011

History of Pockets

Artist: Pickering, 18th c. Because pockets are sometimes hidden from view, it is difficult to know, from images alone, when pockets first became a standard part of an ensemble. I found a fascinating article about pockets on the Victoria and Albert Museum website, a valuable resource for seeing the shape and purpose of ladies' and men's pockets in the 19th century, the setting for my current work-in-progress. In addition, the website has illustrations as far back as the 17th century.

Artist: Pickering, 18th c. Because pockets are sometimes hidden from view, it is difficult to know, from images alone, when pockets first became a standard part of an ensemble. I found a fascinating article about pockets on the Victoria and Albert Museum website, a valuable resource for seeing the shape and purpose of ladies' and men's pockets in the 19th century, the setting for my current work-in-progress. In addition, the website has illustrations as far back as the 17th century.

Pockets tied to doll petticoat In the 18th century, pockets were underneath ladies' petticoats, as seen in photo at the right. Men's pockets were sewn into coat and breeches' linings, much as they are today.

Pockets tied to doll petticoat In the 18th century, pockets were underneath ladies' petticoats, as seen in photo at the right. Men's pockets were sewn into coat and breeches' linings, much as they are today.

Because there was less privacy in previous centuries, when families frequently shared rooms, people sometimes kept their personal possessions in their pockets.

Before handbags came into general use, pockets were used as a carryall, where ladies could carry common articles like thimbles or scissors, as well as money, snuff boxes, smelling salts, or even food and a bottle of gin.

For detailed photos and further information, go to the Victoria and Albert Museum website.

Artist: Pickering, 18th c. Because pockets are sometimes hidden from view, it is difficult to know, from images alone, when pockets first became a standard part of an ensemble. I found a fascinating article about pockets on the Victoria and Albert Museum website, a valuable resource for seeing the shape and purpose of ladies' and men's pockets in the 19th century, the setting for my current work-in-progress. In addition, the website has illustrations as far back as the 17th century.

Artist: Pickering, 18th c. Because pockets are sometimes hidden from view, it is difficult to know, from images alone, when pockets first became a standard part of an ensemble. I found a fascinating article about pockets on the Victoria and Albert Museum website, a valuable resource for seeing the shape and purpose of ladies' and men's pockets in the 19th century, the setting for my current work-in-progress. In addition, the website has illustrations as far back as the 17th century.

Pockets tied to doll petticoat In the 18th century, pockets were underneath ladies' petticoats, as seen in photo at the right. Men's pockets were sewn into coat and breeches' linings, much as they are today.

Pockets tied to doll petticoat In the 18th century, pockets were underneath ladies' petticoats, as seen in photo at the right. Men's pockets were sewn into coat and breeches' linings, much as they are today.Because there was less privacy in previous centuries, when families frequently shared rooms, people sometimes kept their personal possessions in their pockets.

Before handbags came into general use, pockets were used as a carryall, where ladies could carry common articles like thimbles or scissors, as well as money, snuff boxes, smelling salts, or even food and a bottle of gin.

For detailed photos and further information, go to the Victoria and Albert Museum website.

Published on June 12, 2011 13:38

May 31, 2011

History of German Breweries

In researching for my latest novel, I discovered an interesting website which tells the story of German brewing. Surprisingly, I learned that the enterprise of beer making was intertwined with the politics and religion of Germany from as far back as Caesar's time, when his legions were menaced by brewers in the forest clearings.

In researching for my latest novel, I discovered an interesting website which tells the story of German brewing. Surprisingly, I learned that the enterprise of beer making was intertwined with the politics and religion of Germany from as far back as Caesar's time, when his legions were menaced by brewers in the forest clearings.Louis Pasteur's interest in fermentation led to a discovery that saved countless lives, and it all began with his experiments with beer and wine. To read further, and trace the development of ale to lager, and learn who controlled the brewing of beer during specific time periods, go to www.germanbeerinstitute.com/history.html

Published on May 31, 2011 08:35

May 6, 2011

Win a Hardcover Mystery from Edgar winner

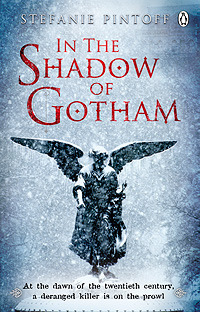

Today I welcome Stefanie Pintoff, author of historical mysteries. Last week I reviewed her debut mystery, which won a coveted Edgar award for Best First Novel. Today, she's giving away signed copies of her latest mystery, Secret of the White Rose, to TWO lucky people who leave a comment.

Today I welcome Stefanie Pintoff, author of historical mysteries. Last week I reviewed her debut mystery, which won a coveted Edgar award for Best First Novel. Today, she's giving away signed copies of her latest mystery, Secret of the White Rose, to TWO lucky people who leave a comment.I've asked her to give a brief summary about the statuary that appears on the cover of one of her books. Even if you live far from New York, as I do, I found the story fascinating. Here it is, in Stefanie's own words.

Throughout my historical mystery series, which began with In the Shadow of Gotham, I regularly include several major New York City landmarks. While my early 1900s setting can sometimes feel far removed from 2011, these places can be strikingly familiar to readers – and help develop a sense of being connected with the past. But it's important to realize that New Yorkers of a hundred years ago sometimes viewed these landmarks very differently than we do today.

Throughout my historical mystery series, which began with In the Shadow of Gotham, I regularly include several major New York City landmarks. While my early 1900s setting can sometimes feel far removed from 2011, these places can be strikingly familiar to readers – and help develop a sense of being connected with the past. But it's important to realize that New Yorkers of a hundred years ago sometimes viewed these landmarks very differently than we do today. One such landmark is the Angel of the Waters, who appears both on the cover of my first book and as well as in its chapters. In cover artist David Rotstein's creation, she is a dark figure bathed in light, yet clothed in ice; reaching out, yet remaining aloof as cold snow swirls around her. The UK edition kept her as their cover figure, but accentuated her darkness as well as the heavy snow surrounding her.

In real life, she was one of the few sculptures commissioned specifically for Central Park. Her creator, the sculptor Emma Stebbins, was the first woman to be charged with creating a major work of art in New York City. Stebbins wanted to celebrate not only Central Park, but also the new Croton Aqueduct that fed the fountain and gave New York City its first dependable source of clean drinking water. So Stebbins's Angel, who presides over Bethesda Terrace, carries a lily (the symbol of purity) in one hand and reaches out with the other to bless the water of the lake (which represents all New York's fresh water supply). Stebbins may have been inspired, too, by a biblical passage about the healing powers of the pool of Bethesda in Jerusalem. As Sara Cedar Miller has suggested in Central Park, An American Masterpiece, this aspect of the Angel perhaps came from the sculptor's personal life. Stebbins' companion, the famous actress Charlotte Cushman, battled breast cancer until her death – and sometimes sought water treatments during her illness.

Yet the Angel of the Waters was reviled when she was first unveiled in Central Park on June 1, 1873. The New York Times stated: "All had expected something great, something of angelic power and beauty." Instead, the crowd's disappointment was palpable. According to the Times, the angel looked like nothing more than a "servant girl" from the rear, and a "girl jumping over stepping stones" from the front. Her head was judged to appear male, but the rest of her body was a mix of male and female parts. And her wings were "unconnected" to her body, put on like a "ballet costume." In short, "the revulsion of feeling was painful."

That's a 19th-century sentiment I don't share. Her area of Central Park is one of my favorite landmarks in all of New York City. It's why I set one of my key chapters in the book around her.

That's a 19th-century sentiment I don't share. Her area of Central Park is one of my favorite landmarks in all of New York City. It's why I set one of my key chapters in the book around her. And I'm not alone. Today, she's one of the most photographed fountains in the world – a celebrity who has appeared in key scenes in Ransom, Bullets over Broadway, Angels in America, Enchanted, and countless others. Each testament to the fact that even landmarks, apparently, can be late-bloomers – especially as generations pass and artistic values change.

For more on Stefanie Pintoff, visit http://www.stefaniepintoff.com/

Published on May 06, 2011 12:16