Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland

September 5, 2025

Elegy Written in a Westwood Burial Ground

Recently I attended an event both sad and uplifting: a memorial service for Frances Doel, who wasRoger Corman’s right-hand woman for decades. The high esteem in which she washeld by everyone who knew her was indicated by the who’s-who list of attendees,including producer Gale Anne Hurd, who credits Frances with being the veryfirst to read and support her and James Cameron’s landmark script for Terminator.

Frances’ celebration of life, wonderfully stage-managed byher sister Rosemary, was held at what is now called Pierce Brothers WestwoodVillage Memorial Park. As cemeteries go, it’s tiny, and tucked away behindoffice towers that make it hard to find. But it dates back to 1905, and hasbeen an interment site of choice for many well-known members of the Hollywoodcommunity. That’s why it’s a popular draw for tourists. L.A. has severalcelebrated burial sites that attract looky-loos. Hollywood Forever cemeterynear Paramount Studios boasts the celebrated wall crypt that holds the remainsof Rudolf Valentino and for years was ritually visited by the mysterious Ladyin Black. (Hollywood Forever also hosts an annual summer film series on itssprawling lawn.)

Westwood Village Memorial Park is known, first and foremost,as the final resting place of Marilyn Monroe. I couldn’t resist seeking out hersite, and admiring the fresh flowers in a vase next to her wall plaque.Famously, right next door to Marilyn is Playboy honcho Hugh Hefner,although his flowers are fake (which seems rather apt). On my leisurelystroll through the premises on a very hot day, I missed many other famousnames: among them Burt Lancaster, Natalie Wood, Dean Martin, Ray Bradbury, andBilly Wilder. Still, I saw some historicresting places, like that of early director Josef von Sternberg, celebrated today fordirecting Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. Kirk and Anne Douglas share asimple space that also bears a poignant reference to their troubled son Eric,who died young. Screenwriter Ernest Lehman’s gravestone sums up a busy,fulfilling life; composer Ray Coniff’s boasts a snatch of one of his mostpopular musical themes. Carl Wilson of The Beachboys is memorialized as “theheart and voice of an angel.” Soul singer Minnie Riperton (mother of MayaRudolph), is honored by the presence of some actual CD’s of her work. Anynative Angeleno will be especially moved, I think, by the joint resting placeof Harry and Marilyn Lewis, whose Hamburger Hamlet restaurant chain was thebackdrop for our growing-up years.

Most eccentric gravesites? Comic actor Don Knotts has aplaque etched with images of him in highly familiar roles, like Mayberry DeputyBarney Fife. The splashiest site I saw belonged to German-born filmmakerWolfgang Petersen, whose most celebrated work was 1981’s World War II submarinedrama, Das Boot. (His ample section boasts candles, a world globe, landscaping,and a lot of fabric roses.) I also appreciated the sites of more modestHollywood figures, like one Jeff Morris, whose plaque describes him as fineactor, and records what must have been a favorite phrase: “weather permitting.”

But of course not everyone interred here has a Hollywoodconnection. I don’t know who Rita Kaslov was, but her stone contains her photo,as well as the information that she was a psychic. At bottom, passers-by canread an advertisement for her services: there’s the image of a hand,fingers outstretched, and theannouncement that she offers $5 palm readings. It’s impossible to say where thelate Rita is now, but I’m sure she has gained a lot of insights since sheshuffled off this mortal coil.

September 2, 2025

Beating a Tin Drum

Decades ago, on assignmentfrom the Hollywood Reporter, I wrote an article on child actors who wererequired to perform in very adult situations. I came away disturbed butfascinated by parents who allowed—or even encouraged—their kids to play rolesthat involved heavy doses of sex or violence. The parents, and the kids themselves, all insisted that there had beenno harm done, but a child psychologist I interviewed wasn’t so sure that theyoungsters ultimately came away unscathed.

So you can imagine howcurious I am about Daniel Bennent. The Swiss-born actor is 58 now, andapparently doing fine. But he was a mere 11 when he starred in VolkerSchlöndorff’s bold 1979 adaptation of a tragicomic German anti-warnovel, Günter Grass's The Tin Drum. The film(distributed in the U.S. by Roger Corman) shared the Palme d’Or at Cannes with ApocalypseNow, and went on to win the 1980 Academy Award for best foreign language feature.

Bennent, the child of actors,apparently got the plum leading role because of a medical condition that stuntedhis growth at an early ago. Oskar, the boy he plays, has made the eccentricchoice not to grow any taller once he’s reached the age of three. So at 11 andat 16 and at 19, he’s still got the look of a very young boy. It’s not just his height that’s distinctive: he has asolemn face marked by an intense blue-eyed stare that keeps the audienceriveted. And then there’s the toy drum (a gift from his sensual and eccentricmother) that’s his constant companion, something he turns to at moments of highemotion, rapping out his feelings with two wooden sticks. (He also depends on ashriek that can literally shatter glass.) In the course of the film, though his body stays the same, his spiritdefinitely evolves, leading him to discover lust and ultimately sorrow.

Oskar and his family live inDanzig, an independent coastal city that’s a blend of German and Polishinfluences. It’s the 1930s, and Nazi ideology is definitely on the rise. Insome ways it divides his household, which is an unusual one. Mother Agnes seemsto split her attentions (sexual and otherwise) between her shopkeeper-husbandand the male cousin who shares Oskar’s bright blue eyes and is quite probablyhis biological parent. The two dad-figures are on opposite sides of the town’spolitical and ethnic divide, and ultimately both face tragic fates, with Oskaralways sensing that he’s a slight bit responsible.

Following the loss of hismother and both father-figures, Oskar is drawn less to political ideology thanto the simple need to survive. Which is how he ends up in a circus actfeaturing a cynical band of what we might call munchkins, all of them far olderthan he but not much taller. They perform for Nazi troopers who greet themgleefully, but they find their happiness (not to mention sexual gratification)within their own ranks. This is not to be the end, though, of Oskar’s odysseythrough wartime Europe. He winds up back where he started, finally making thecurious decision to start growing once again.

The cinematography of TheTin Drum is often distinctive, and the European cast is strong. I want tosingle out Charles Aznavour, knownworldwide as a French singer/songwriter of Armenian descent. He was also alifelong supporter of human rights. In The Tin Drum he has the small butvital role of a kindly Jewish toy-shop owner who (of course) meets a sad fate,and he’s not easily forgotten.

August 29, 2025

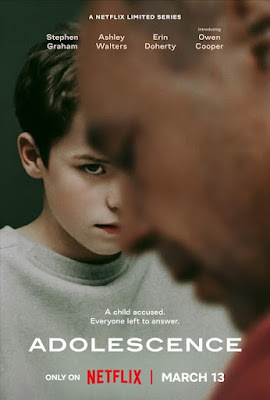

Growing Pains: Exploring “Adolescence”

Adolescence is a bland-sounding title for a limited TV series outof Britain that has accumulated eleven Emmy awardnominations. Winners in this prestigious category have included, over the decades, some of TV’sbest dramas, including Angels in America, The Queen’s Gambit, andseveral of Tom Hanks’ historical re-creations, including Band of Brothers andThe Pacific.

Adolescence is a bland-sounding title for a limited TV series outof Britain that has accumulated eleven Emmy awardnominations. Winners in this prestigious category have included, over the decades, some of TV’sbest dramas, including Angels in America, The Queen’s Gambit, andseveral of Tom Hanks’ historical re-creations, including Band of Brothers andThe Pacific. I have no crystal balltelling me who will take home the Emmy on September 14. I’m sure there are goodthings to be said about the other nominees: Black Mirror, Dying for Sex, Monsters: The Lyle and Erik Menendez Story, and The Penguin. But I’ll be rooting for Adolescenceto nab the top prizes in this category, both because of the importance ofits ideas and the excellence of its craft.

Adolescence has been widely described as a psychological crimedrama, and this is accurate, as far as it goes. At its center is a murder, andthe killer’s motives are certainly open to question. But there’s no emphasishere on tracking down the bad guy; this is not a case of rising suspense as thenoose tightens. First of all, we know almost from the very beginning that thekiller is an innocent-looking 13-year-old boy, who has dispatched a femaleclassmate with multiple stabs of a knife. The real question is: why did thishappen? Over the course of four one-hour episodes, the impact of the killing isapproached from four very different angles. What makes for exciting televisionis the fact that each of the four has a different focus, requiring us to see abloody but straightforward deed from very different perspectives.

And, thrillingly, each ofthese four episodes is shot in a single (though very complex) take, which hasthe effect of drawing us into what seems like a televised reality program. Thisis especially true of Episode 1, in which—without preliminaries—a heavily armedpolice squad bursts into a working-class English home, terrifying itsoccupants. They head directly for an upstairs bedroom where a boy cowers inbed, in a room brightly decorated with outer space images. Jamie is told to getdressed, then is hustled out of the room, leaving his well-worn teddy bearbehind. The murder charge seems as impossible to us as it does to his parentsand sister, and Jamie denies everything. Throughout we can’t help admiring theprofessional way the British cops make sure his rights are protected.

Episode 2 is led by a policedetective who visits the school attended by both killer and victim. Again theemotions are raw, as students mourn their dead classmate and try to avoid beingin any way implicated in the tragedy. But Detective Bascombe’s own son, anolder student at the school, clues his father in to Instagram practices thatmay hold a clue to what’s going on.

The heart of the drama isEpisode 3, entirely devoted to a session between Jamie and a forensicpsychologist. Here for the first time we grasp the complexity of the youngman’s emotions (Owen Cooper became theall-time youngest Emmy nominee in this category for this episode), and also thetoll they take on his professional but kindly questioner.

Perhaps the biggest surpriseis Episode 4, in which Jamie (facing trial) is only a voice on the telephone.That’s because we’re focused entirely on his well-meaning parents, who feeltremendous guilt for their son’s actions. The father, movingly played byStephen Graham (also the co-author of the series) is a kind, serious mandevoted to family life. Could he have stopped this tragedy? Could anyone?

August 26, 2025

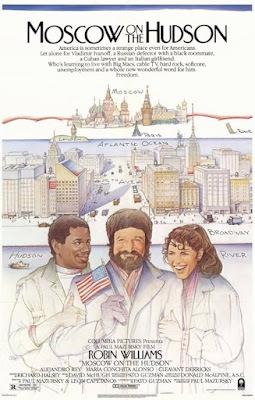

Leaving Home to Find a Home: “Moscow on the Hudson”

There are émigrés from Soviet Russia in my extended familycircle, so I’ve heard plenty of stories about the bad old days in the USSR. Andthis year’s Oscar-winning Anora gave me an indelible glimpse of today’sglobe-trotting Russian oligarchs, as well as the pockets of old-school Russianculture in New York’s Brighton Beach. All of which made me eager to enjoy RobinWilliams in Paul Mazursky’s gentle 1984 comedy about a defector from Moscow inthe era of Ronald Reagan.

The film is an extended flashback, following a glimpse ofWiliams’ Vladimir Ivanov showing a newer arrival to NYC the ropes. So we knowfrom the start that nothing very terrible is going to happen to Vladimir afterhe impulsively decides to make New York City his new home. Vladimir, asaxophone player with a great love of American jazz, has traveled to the BigApple as part of a Russian circus troupe. On the group’s last day, during aquickie group shopping spree at Bloomingdale’s, he suddenly eludes the grim-facedSoviet minders and declares his intention of staying on in this “decadent” newland. His impulsive decision of course has major consequences: the Americanpublic and America media briefly rally on his behalf, but he’s cut off foreverfrom the close-knit Russian family he loves.

Mazursky, always good with social details, researched lifein 1980s Moscow and blended this with his own grandfather’s memories of emigratingfrom Ukraine to the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century. For me (and formany critics) the film’s richest moments come in its first third, when we areintroduced to Vladimir in the context of his Old World relatives. We spend timein their cramped apartment, and see their heartfelt joy when Vladimir comeshome with gifts: he’s braved a very long line in order to successfully purchasearmloads of toilet paper rolls. He’s saved one roll as a romantic offering tothe curvaceous young woman he habitually beds in the flat borrowed from afriend, Anatoly, for this purpose. Anatoly, one of the clowns in Vladimir’scircus, brashly declares himself desperate to leave the Soviet Union in searchof the freedoms promised by the U.S.A. But though Anatoly speaks often about defecting, he ultimately can’tbring himself to take the risk. (He’s played by the Latvian-born Elya Baskin,whose tragicomic face I’ll long remember.) Anatoly’s ultimate fear of making achange is why Vladimir’s impulsive action is such a surprise to those aroundhim. And the moment of hisdefection—complete with security guards, the press, the FBI, a very gay Bloomie’ssalesclerk, and a lot of others—is hilarious.

From this point forward, the film loses some steam, spendingmuch of its time on Vladimir’s on-again-off-again romantic relationship with apretty Italian-born salesclerk played by Maria Conchita Alonso (who’s notexactly Italian, but you get the idea). Part of Mazursky’s point is that inAmerica almost everyone (aside from some key African American characters) is arecent arrival from somewhere else. And immigration is portrayed in such aglowing light that I could only shake my head at how times have changed.There’s a touching little scene in which Alonso’s character and a host ofothers ceremonially take the oath to become U.S. citizens. And in a diner,after a worn-down Vladimir dares to briefly criticize his new country, theother patrons—from a host of cultures—take him to task, even movingly recitingfrom the Declaration of Independence about how all men are created equal. Wecertainly need some of that idealism today.

August 22, 2025

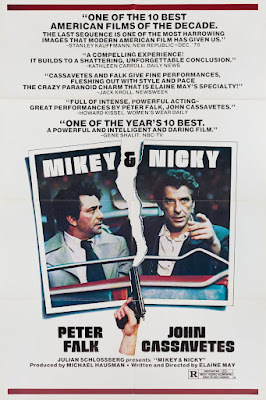

Boys Will Be Boys: “Mikey and Nicky”

Elaine May has always had afraught relationship with Hollywood. After her early glory years as one-half ofthe Nichols and May comedy duo, she wrote and directed her first feature film,a pitch-black comedy called A New Leaf, in 1971. It fared poorly at thebox office, but is now considered a cult classic, inducted in 2019 into theNational Film Registry of the Library ofCongress. The following year, May directed a Neil Simon script that became amajor hit: The Heartbreak Kid, starring Charles Grodin as a jerk who dumpshis annoying bride (May’s daughter Jeannie Berlin) during their honeymoon andjumps into bed with a beautiful blonde (Cybill Shepherd). Frankly I’ve oftenfound this film disturbing in its reliance on ethnic stereotypes, but audiencesresponded with glee, and Berlin won several major awards for her outrageouslyunattractive portrayal.

So May was riding high thefollowing year when she wrote and shot Mikey and Nicky (1976), aso-called “neo-noir” starring good friends Peter Falk and John Cassavetes. WhenI watched this film, I knew nothing about where it was going. Frankly, Ithought it would play up the comic aspects of a longtime relationship. And soit did, if you like your humor very dark indeed. The film, set amid the squalorof an east-coast city, starts with Cassavetes’ Nicky holed up in a seedy hotelroom, frantically summoning his lifelong pal Mikey to save him from the wrathof a boss who’s clearly a dangerous thug. (He’s played by the legendary actingcoach Sanford Meisner.) There are some laughs to be had in Mikey (Falk) showingup with a cache of Gelusil for his buddy’s ulcer and then trying to hustle himout of town.

Thus begins an odyssey inwhich the half-crazed Nicky keeps getting distracted from his own escape plans,with Mikey keeping him company every step of the way. The full story of theirrelationship unfolds particularly in a midnight over-the-wall jaunt into alocal cemetery. There we come to fully understand how long these two have beena part of one another’s lives, sharing tender memories of family members nowlong gone. They also almost share the favors of a (sort of) prostitute: it’sher angry rejection of Mikey that becomes one of the film’s key turning points.

h both men are husbandsand fathers of young children, they are not what I’d call mature adults. Intheir slightly different ways they treat women badly: Nicky has destroyed hismarriage (to one of my longtime favorites, Joyce Van Patten) with his overtphilandering; Mikey treats his wife better but clearly doesn’t regard her as anequal. Certainly he doesn’t share with her his many secrets, including the factthat his younger brother died in childhood The film suggests that the centralrelationship in Mikey and Nicky’s lives is with one another, with all thatimplies about nostalgia, affection, and jealousy. Which makes the film’s ending truly poignant.

From what I’ve read, ElaineMay did herself no favors on the set of Mikey and Nicky. Determined tocapture the improvisational style of her two leads, she spent far more time andmoney on the film than her studio had allotted. (I’ve learned she shot almostthree times as much footage as was required for Gone With the Wind.) That’s why the final cut was taken away fromher, and the version rushed into theatres by Paramount was haphazard at best.It was 1986 before a May-approved version finally emerged. And she didn’tdirect again for eleven years. Yes, it was the notorious Ishtar.

August 19, 2025

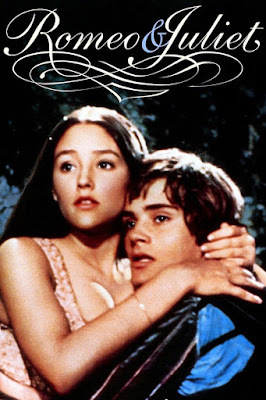

Juliet . . . & (eventually) Romeo

Methinks that every generation has its own Romeo andJuliet, in which the tragic lovers reflect the concerns of the day. The1936 film directed by George Cukor came out in the midst of the GreatDepression. This was a time when young people going the movies craved glamourand sumptuous production values, things they couldn’t find in their own dailylives. Cukor’s MGM-based production featured major (though overaged) stars.Leslie Howard, as Romeo, was in his forties, and Norma Shearer, who playedJuliet (and was married to studio honcho Irving Thalberg), was about 34, morethan double the age of Shakespeare’s teenage heroine. The film was shotdecorously, on elaborate sets, and given the full prestige treatment, completewith splashy roadshow engagements where illustrated programs were sold. (Yes,my mother bought one, and saved it for many decades)

More than 20 years later, in 1957, a much-updated version ofRomeo and Juliet became the toast of Broadway. This of course was WestSide Story. The Leonard Bernstein-Stephen Sondheim musical reimagined thestar-crossed lovers as recent New Yorkers from rival cultural backgrounds, withTony as a Polish-American founder of a street gang called the Jets, and Maria,newly arrived from Puerto Rico, as naturally affiliated with the Sharks. Thehit play became in 1964 a mega-hit film that gobsmacked everyone at my highschool. We were much taken, in that era, with the promise of social justice forall, and the tragic story of lovers unable to transcend the enmity all aroundthem hit us hard. (Steven Spielberg’s 2021 rethinking of the same musical hasits merits, but its box-office reception was far less overwhelming, probablybecause the concerns of moviegoers had much changed in the interveningfifty-plus years.)

What I consider MY Romeo and Juliet was the FrancoZeffirelli version that came out in the fraught year 1968. It was filmed onlocation in medieval Italian towns, and was the first cinematic version tofeature actors close in age to Shakespeare’s actual characters. Zeffirelliapparently considered casting Paul McCartney and other rock gods of the era,but ended up with two unknowns, Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey, who werecast when they were 16 and 15, respectively, but aged a year in the course offilming. We college students of the era, many caught up with our own first bigromances, watched this movie in a sort of swoony daze, fully understanding theerotic passions of the two young lovers.

Leave it to Baz Luhrmann to jazz up the Shakespearean story,giving it a kind of hipster sensibility. The year was 1996, and the stars wereLeonardo DiCaprio (then 21) and Claire Danes (about 17). The feuding familieswere played as 20th century Miami mobster types, with the Capuletsnow having some Latin roots. The setting was Verona Beach, and one key scenewas played in a swimming pool. There’s still some well-spoken Shakespearean poetry,but also guns and party drugs.

I’m reminiscing about all this because I’ve just seen theL.A. stage production of & Juliet, a London and Broadway hit musicalthat posits Juliet (waking in the tomb beside the dead Romeo) deciding notto kill herself for love. What follows is a riotous comedy in which pop songs fromMax Martin are incorporated into Juliet’s romantic adventures in Paris.(Brittany Spears’ “Oops!... I Did It Again” becomes an acknowledgement thatJuliet falls for cute guys a tad too quickly.) The many teens in the house cheeredfor Juliet’s developing feminist consciousness and for the “woke” gayempowerment motif that predominates. Me? I just felt rather old.

August 15, 2025

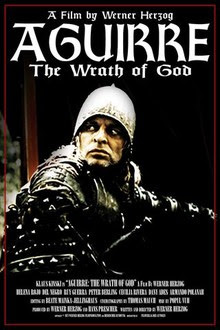

God and Gold: “Aguirre, The Wrath of God”

Circa 1982, my once andfuture boss Roger Corman signed on to help distribute Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo,a bizarre adventure set in the jungles of the Amazon. This was during aten-year period, starting with Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, when Roger went all in on the Americandistribution of outstanding European art films.

Ten years earlier, Herzog hadmade another challenging film set in the rainforests of Peru. It was this earlierfilm that helped give him an international reputation, and it starred the sameactor—the manically intense Klaus Kinski—who was later to be at the center of Fitzcarraldo,the story of a 20th century man obsessed with the bizarre idea ofbuilding an opera house in the jungle. Aguirre, the Wrath of God isa period piece, vaguely linked to historic fact, in which a troop of Spanish conquistadoresand their local minions hack and raft their way through Amazon rain forests ina bid to find the fabled lost city of El Dorado.

Aguirre, a mere 94 minutes long, begins with a slow stretch inwhich a long line of Pizarro’s Spanish soldiers (as well as slaves, indigenousconscripts, Catholic priests, and—to our surprise—a few elegant ladies in sedanchairs) inch their way through a challenging landscape, from lofty mountaintopsdown to the Amazon River. So slow-moving is this opening section that I suspectthe always impatient Roger Corman would have been itching to trim it, if he hadany say in the matter. I got a bit restless too, but my hunch is that Herzogwas here sending us a message—that this film would require us to step outsideof time and give in to the plodding nature of the actual and the symbolicjourney.

And what a journey! Early on,Pizarro recognizes that it might be pure folly to send the entire regiment insearch of an enigmatic city of gold. That’s why he creates a small squadron ofmaybe forty people and sends them off on rafts, giving them two weeks to returnwith some usable intel. Things go badly from the start: there are perilous ripcurrents that trap some of the travelers, as well as concealed but deadlyIndian tribes who oppose incursions into their territory. In the face of thesechallenges, genteel and steady commander Don Pedro de Ursúa is overthrown in amutiny led by the brooding Don Lope de Aguirre.

From the moment we first spothim, it’s clear that Aguirre (played, of course by Klaus Kinski) is dangerous. Youhave only to look into his pale blue eyes to see the madness blazing within. He’sa man caught in the grip of an obsession: to find El Dorado and seize itsgolden treasures, thus ensuring himself fame as well as fortune. Though otherson the trek focus on spreading the glory of God, he himself is fixated on thegold he believes awaits those bold enough to find and claim it.

The last section of the filmconcentrates on the way the trip implodes, with those still alive (thoughstarving and debilitated) seeming to lose all touch with reality. Aguirre, wholikes calling himself “the wrath of God,” is predictably the last man standing.But his vision of the future contains ominous (and sexually perverse) elementsI would rather not discuss. And then there are those visitations from whatseems to be another world, but perhaps is just the natural order striking backat man’s hubris. I know one thing: I don’t want to see Klaus Kinski in mydreams.

August 12, 2025

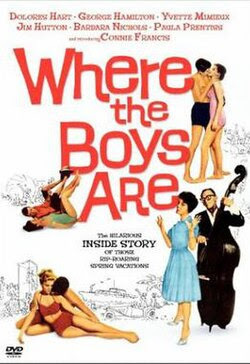

Where the Boys Are: Remembering Connie Francis

`The passing of plaintive songstress Connie Francis broughtme back to my teen years. Francis—whose early pop hits included “Stupid Cupid,”“Lipstick on Your Collar,” and a swoony rendition of the old “Who’s SorryNow?—played featured roles in movies and then segued into belting out standardsfor adult audiences. Hers was an eventful life: her father chased away an earlysuitor, the pre-fame Bobby Darin, and none of her four subsequent marriagesended well. In 1974, while staying post-concert at a Howard Johnson’s motel inupstate New York, she was raped at knifepoint, left naked and tied to a chairby an assailant who was never found. Other family tragedies and healthchallenges followed, but she eventually resumed her singing career, became avictims’ rights advocate, and survived until the ripe old age of 87.

I will always associate Connie Francis with Where theBoys Are, a 1960 film seen (sometimes more than once) by every junior highschool girl I knew. The film was in many ways a template for the beach partymovies that followed (as well as for aspects of Roger Corman’s New WorldPictures nurse flicks). We girls appreciated Where the Boys Are forzeroing in on the hopes and fears with which we regarded our own futures. Ourimpending college years—still far off but looming large in ourimaginations—seemed to promise so much in the way of freedom, self-fulfillment,romantic love. Still, we could sense that there were dangers to be skirted, andthe film makes these quite clear.

It starts with a group of diverse (but, of course, allwhite) college co-eds heading down from the snowy Midwest to enjoy spring breakin Fort Lauderdale, where vacationing collegians abound. Boys, of course, arevery much on the minds of the four. The sensible Merritt (Dolores Hart) isquickly attracted to Ivy Leaguer Ryder (George Hamilton). Madcap Tuggle (PaulaPrentiss) is delighted to find that TV Thompson (Jim Hutton) is even tallerthan she is, and shares her wry sense of humor. Pretty blonde Melanie (YvetteMimieux) falls hard for a Yalie named Franklin. Angie (Connie Francis) has a fewlaughs with the goofy Basil (Frank Gorshin), but is mostly alone, wistfullywarbling, “Where the boys are . . . someone waits for me.”

All these plotlines play out in ways we can predict. The funand games that are part of this giant courtship dance give way to a more sombertone when Melanie, who has naively agreed to meet Franklin at a local motel,finds herself a rape victim. Dazed and disheveled, she wanders down the highwayand is sideswiped by a passing car. Her hospitalization quickly leads herfriends to step back from their own romantic adventures. Maturity, theyrealize, is something to be prized. At the film’s end they’re returning tocollege, sadder but wiser.

As they recuperate from their spring fling, lessons havebeen learned. (I’m sure our parents appreciated the film sending a cautionarymessage regarding pre-marital sex.) The light-hearted romance of Tuggle and herguy is quickly over (though Prentiss—making her first film—and Hutton had suchstrong on-screen chemistry that MGM quickly starred them in three romanticcomedies). It’s only Hart and Hamilton’s characters who seem to have a solidconnection that can make for future happiness.

The irony, of course, is that Dolores Hart was not destinedfor marriage. In 1963 she ended her engagement to an L.A. architect to enter aConnecticut convent as a Benedictine nun. Clearly, she was not heading wherethe boys are.

August 7, 2025

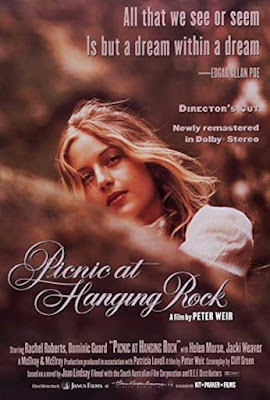

The Serpent in the Garden: “Picnic at Hanging Rock”

Many scholars agree that theAustralian film industry came of age in 1975, when native Aussie Peter Weirdirected Picnic at Hanging Rock. This complex psychologicalthriller—filmed in South Australia with state funds and an Australiancast—became an international success story, though its ambiguity was not toevery taste. On the strength of this film and such other Australian projects asGallipoli (1981), Weir carved out a major career in Hollywood, startingwith Witness and including such distinctive features as Dead PoetsSociety (1989), and The Truman Show (1998)

From the film’s first fewmoments, it’s clear that Weir is brilliant at giving a visual flair to hisstories. This one, based on a popular Australian novel that hints that thestory it tells is true, begins on the morning of Valentine’s Day in the year1900. We’re in the countryside, at a school for well-bred young ladies, most ofwhom are thrilled to be going on a rare outing to a natural landmark a fewhours away. For the occasion, all are decked out in pristine white dresses(it’s summer in Australia) along with black stockings and shoes. They’ve letdown their hair, and for once have been allowed to remove their little whitegloves once they near their destination.

It's a prim group,apparently, though there are hints from the start that some of them are chafinga bit at all the restrictions placed on them by their strict headmistress andher faculty. They may be tightly corseted beneath their summer frocks but theiremotions are running wild and free, as we see when they exchange surprisinglypassionate Valentine messages. Once they arrive at the distinctive volcanicoutcropping known as Hanging Rock, they seem to let down their guard, as dotheir official chaperones. They’ve been warned not to try to climb the jaggedrock formation because of the many dangers it presents, including insects andpoisonous snakes. And yet a few of them do set off to explore theirsurroundings . . . and several are never heard from again. These includeMiranda—blonde and pretty—who has been singled out early on as someone sure ofher powers and perhaps eager to go her own way. (I kept wondering if her namewas chosen in reference to the heroine of Shakespeare’s The Tempest,someone excited to discover for herself a “brave new world.”)

The mystery of the girls’disappearance is never solved by the filmmakers, leaving some critics andaudiences aghast. Instead the focus is on the reactions of those left behind, survivorswho feel pain for a whole host of reasons. There are the missing girls’classmates, of course, but also the school’s imperious headmistress and herstaff, as well as the local policemen who’ve helped with the search and avisiting English gentleman who’d eyed the pretty young ladies before they wentmissing and becomes almost unhinged after their disappearance. The camera picksup the anguish of all of these folk, but also lingers enticingly on the naturalworld that stands in such marked contrast to the “civilized” strictures of the upper-classAussies of that era. We see those snakes, those insects, those dangerouscritters that the girls had been warned to avoid. But we see beautifulcreatures too, like a majestic swan who glides through the film from time totime, seeming to suggest both purity and proud independence.

Picnic at Hanging Rock is a frustrating film for those who like theirmysteries solved, but it will haunt me for a long time.

August 4, 2025

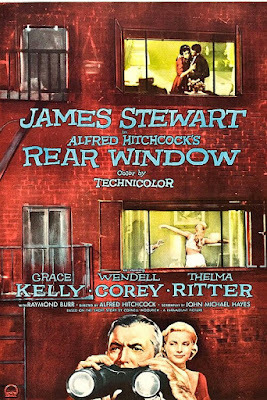

Looking Back at “Rear Window”

When I was much younger, I always had trouble with AlfredHitchcock’s 1955 thriller, Rear Window. Set in New York’s Greenwich Village, it’s the story of Jeff, aglobe-trotting photojournalist (James Stewart), who has broken his leg in theline of duty. Stuck in his tiny upstairs flat, with much too much time on hishands, Jeff has nothing to do but spy on his neighbors, through binoculars, inthe apartment building across the way. Critics discuss this film as anexploration of voyeurism, with audience members essentially joining Stewart asPeeping Toms. Some recent feminist scholars have gone further, seeing RearWindow in terms of the notorious “male gaze,” the way movies are designedto reinforce men’s stereotypes about the women they can’t stop watching.

My problem with the film was this: I too had endured abroken tibia. In fact, I’d endured two, from ski accidents a year and ahalf apart. (Yes, I quit skiing thereafter.) So I was sensitive indeed to anyinaccuracies about life in a plaster cast. I could well understand Jeff’srestlessness, and appreciated the detail of him desperately trying relieve the itchyskin inside the cast by cautiously inserting a long-handled backscratcher. But!Why was he stuck in a wheelchair throughout the film? Why wasn’t there a pairof crutches around? Yes, a few weeks ina thigh-to-toe plaster cast can indeed seem like an eternity, but why was Jeffso helpless, and so miserable, when his cast was apparently due to come off amere seven weeks after the accident, thus implying that the break wasn’t allthat drastic? (Try wearing a cast for six months sometime!)

Fortunately, my legs are both whole these days (knockwood!), which frees me to appreciate Hitchcock’s work on this clever and original film. I was not surprised to learnthat it was made entirely on the Paramount Studios back lot, with Jeff’s fixedpoint of view focused almost entirely ona multi-story apartment building that spreads before him like a stage set. It’sa midsummer heatwave, which means (in anera before the widespread advent of air conditioning) that life plays outthrough wide-open windows and on fire escapes. He’s spent so much timeobserving the building’s inhabitants that he’s given some of them nicknames,like Miss Torso (a curvaceous dancer who seems to have few clothes and a lot ofcompany) and Miss Lonelyhearts (who only pretends to have visitors, and appearson the brink of being suicidal).

One neighbor (played by the hulking Raymond Burr) apparentlylikes growing plants in the building’s small flowerbed, but has no use for hisneighbor’s little dog. He also doesn’t seem, from Jeff’s wheelchair-boundperspective, to have the best relationship with his invalid wife. He’s atraveling salesman, so perhaps it’s not odd that he comes and goes at oddhours, carrying a suitcase. But Jeff is quick to cast him as the bad guy in amurder mystery. Is he?

Jeff’s accomplices in trying to solve this mystery that mayor may not exist include a peppery visiting nurse (the always delightful ThelmaRitter) and a gorgeous socialite (Grace Kelly) who’s deeply in love with him.Kelly’s Lisa Fremont makes old-time viewers like me recall what was so greatabout 1950s fashion. Lisa claims she’sready to give up her lavish lifestyle to join Jeff in holy matrimony; he’sskeptical, and perhaps he has reason to be. In the course of this film sheshows her underlying pluck, but are they ready for happily ever after? That’sone mystery that Rear Window never solves.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers