Chris Sims's Blog

September 15, 2011

The Geek Way

In most dictionaries, the definition of "geek" is way behind the times. It's still classified a pejorative term that implies negative qualities or insular, intellectual behavior. Synonyms include dork, freak, nerd, and weirdo—basically a social misfit.

In most dictionaries, the definition of "geek" is way behind the times. It's still classified a pejorative term that implies negative qualities or insular, intellectual behavior. Synonyms include dork, freak, nerd, and weirdo—basically a social misfit.

The reason I say this sort of definition, and the people who still use it, are behind the times is because geek has been moving toward chic since Revenge of the Nerds (1984) was in theaters. As the dorks of the 80s grew up and became business leaders, computer specialists, game designers, scientists, writers, and other sorts of accomplished professionals, "geek" has become synonymous with success and disposable income.

The word is also used in common parlance to denote someone who is passionately enthusiastic, in a positive way, about a subject, job, or hobby. You can be a kayaking geek, a computer geek, a yoga geek, confectioner geek, and so on. In fact, most mature geeks I know fit into a range of geek types rather than single-minded enthusiasts. Plenty of "cool people" self identify as some sort of geek.

I'm a gaming geek. Chances are, since you're reading this, so are you.

Other than being passionate about games, gaming geeks are often considered to be extremely cerebral and introverted. We can be pedantic, judgmental, and cliquish. All these traits can lend to the social-misfit stereotype, especially in a culture where "intellectual" is sometimes touted as an unfavorable trait. The basement-dwelling troglodyte cliché persists despite the fact that geekdom has crossed innumerable boundaries.

The worst boundaries I see in my gaming life, however, are those limits we gaming geeks impose on ourselves. Again, we can be pedantic, judgmental, and cliquish, as well as hyperintellectual and plain snobby. Rather than retain a sense of wonder and experiment, we can adhere to onerightwayisms and badwrongfunisms. We define ourselves as simulationists or gamists, roleplayer or tactical, video gamer or tabletop gamer, as if those terms have any extant value beyond the realm of personal preference. Forgetting that our games and their settings are imaginary, we look for truths in them and about them. Such "truths" are no more existent than the made-up milieus to which we apply them. (Stephen Radney-MacFarland of NeoGrognard is a great one to discuss this subject with.)

Don't feel persecuted if you believe you're in such a category. I've been there, too. But I've been blessed with diversity of exposure and experience that has made me see the error of my ways. In the domain of personal fantasy and fun, the only right way is the one on which the participants agree. "Official" stances, canon, metaplots, and rules be damned.

All games I've played had their value and an influence on my beliefs and design methods. In Wizards R&D, I've gotten strange looks because I said I like GURPS. Sure, GURPS isn't any form of D&D, but it has its virtues and flaws, just like D&D does. Playing GURPS, even as dungeon-crawling fantasy, is less abstract than playing D&D in a similar mode. But GURPS, and its first cousin Savage Worlds, suffers from static disadvantages that characters can have, the roleplaying of which is governed only by the vigilance of the GM and player.

All games I've played had their value and an influence on my beliefs and design methods. In Wizards R&D, I've gotten strange looks because I said I like GURPS. Sure, GURPS isn't any form of D&D, but it has its virtues and flaws, just like D&D does. Playing GURPS, even as dungeon-crawling fantasy, is less abstract than playing D&D in a similar mode. But GURPS, and its first cousin Savage Worlds, suffers from static disadvantages that characters can have, the roleplaying of which is governed only by the vigilance of the GM and player.

FATE (Dresden Files RPG) and Cortex+ (Leverage RPG and Smallville RPG) handle the flawed character better through use of dynamic currencies that encourage implementation of the flaws in the game. Each of these games has something D&D could learn from, and has or will in my home games. (These games can also learn from other games, as I hear Margaret Weis Productions might soon show us.) Similarly, if I were ever to run a Pathfinder or 3e D&D campaign, I would derive some of that campaign's GMing tools, such as monster and NPC design, from 4e D&D.

The point is: As my repertoire of played games expands, including videogames, so does my viewpoint on how games might be designed and played. I've learned you have to play a game to have the most qualified opinion on it. Reading it or looking on from the outside is not enough. Claiming to like or dislike a game, implying your opinion is somehow educated, without experiencing that game is disingenuous. (I did this in a review of Mutants & Masterminds, the flaws of which show up pretty quickly in play—for example how Toughness works.) Saying your way of playing is somehow the one true way is snobbery.

When it comes to D&D, or any RPG really, I have yet to see a wrong way to play.

My friends and I, as kids, flipped through the 1e D&D monster books, which for us included Deities & Demigods, with our 10th-level characters to find a creature we couldn't beat. Of course, we had unbalanced characters. I'd like to have met a 10-year-old D&D player in the 80s who didn't. We added all sorts of stuff to our game from everything we read, saw, and listened to. Yes, some of our characters had lightsabers, and others had boots like Gene Simmons of (makeup-wearing) KISS. To more than a few of us, that stuff is still cool.

My friends and I, as kids, flipped through the 1e D&D monster books, which for us included Deities & Demigods, with our 10th-level characters to find a creature we couldn't beat. Of course, we had unbalanced characters. I'd like to have met a 10-year-old D&D player in the 80s who didn't. We added all sorts of stuff to our game from everything we read, saw, and listened to. Yes, some of our characters had lightsabers, and others had boots like Gene Simmons of (makeup-wearing) KISS. To more than a few of us, that stuff is still cool.

As countless other grognards and game designers have admitted and opined on, we ignored parts of older D&D that were too arcane for us. Weaned on basic D&D, and without the cash flow to assemble armies of lead figurines, we took to Advanced D&D with that simpler sensibility. We rarely used the battle grid, although the game and its statistics called for it even then. Therefore, we ignored weapon and spell ranges, and we fudged whether monsters ended up in blast radiuses. Now that I think about it, even with our lightsaber-wielding uber-characters, we emphasized what was fun for us.

That's the key, I guess. And lots of styles can be fun.

My teenage simulationist streak is what got me into games such as Rolemaster and GURPS. Back then, I might not have tried James Wyatt's Random Dungeon(TM), which has about as much story as Hack or Rogue. (Both of which are fun, as is JW's Random Dungeon.) I would have appreciated Mike Mearls's love of dungeon crawling a lot less and been unwilling to participate in a 3e reboot game he ran. In fact, I might have disdained the typical limitations of convention play. It would have been snobbery and my loss in every case.

Play style is just that. If you aren't participating in a given game, it's not within your purview to judge that game negatively unless you intend to be unkind. (You can judge, in a general sense, any game you've played, especially with reference to your preferences.) In my mind, this point of view applies to published products that don't seem to be your style.

Fourthcore, for example, is hardcore, meat-grinder dungeon crawling in the vein of Tomb of Horrors. To some, it's an experiment with the boundaries of 4e D&D. For a few, it goes too far afield. To me, 4e always contained the possibility of Fourthcore or something like it. My current DMing style is more along the lines of an action/adventure novel or TV series, but I appreciate the fact that D&D, among countless other RPGS, is pliable enough to accommodate so many ways of having fun. Furthermore, I can participate in alternative styles as the opportunity arises.

Just like any of us can be more than one type of geek, and most forms of geekery have positive traits, every game has a range of possibilities. What you prefer might be different, but we geeks can learn from one another, and we gamers and game designers can learn from all sorts of games. Experimentation and exploration expand horizons. Nothing is sacred; everything is permitted. Of course, none of us has the time to try everything, but all of us can avoid negative prejudgment, whether of other people or games. Instead, we can emphasize the positive aspects of our differences, gaining some wisdom in the process.

Just like any of us can be more than one type of geek, and most forms of geekery have positive traits, every game has a range of possibilities. What you prefer might be different, but we geeks can learn from one another, and we gamers and game designers can learn from all sorts of games. Experimentation and exploration expand horizons. Nothing is sacred; everything is permitted. Of course, none of us has the time to try everything, but all of us can avoid negative prejudgment, whether of other people or games. Instead, we can emphasize the positive aspects of our differences, gaining some wisdom in the process.

I want to thank those among you who have taught me new possibilities. I also want to thank those of you who have graced my game table or network connection with your presence. I've stolen good ideas from all of you, or recalibrated my thinking to accommodate a new idea of yours, just so you know. So, I owe you one.

This is my Speak Out with Your Geek Out participation. Why don't you speak out, too?

March 31, 2011

Junk Punch

You have been sucker punched. As a gamer, you've been categorized and used as a negative stereotype to illustrate points about terrible movies. Video games and gamers get a bum rap in film criticism. Film critics seem to like to use video games and the people who play them as a culturally understood idiom. This practice makes the critics look as bad as what they might be criticizing.

You have been sucker punched. As a gamer, you've been categorized and used as a negative stereotype to illustrate points about terrible movies. Video games and gamers get a bum rap in film criticism. Film critics seem to like to use video games and the people who play them as a culturally understood idiom. This practice makes the critics look as bad as what they might be criticizing.

Roger Ebert, with his starkly ignorant opinion of video games as art, might have brought this mistreatment to a head in popular media. This lack of actual cultural awareness has been around for a long time, however, with film critics decrying just about anything that's based on a video game or seems gamish. The trend degenerates from there, with critics using the term "video game" to condemn crappy adventure movies, as well as the term "gamer" to refer to insipid consumers of such dreck. This sort of condescension is a refuge only of someone who can't come up with a meaningful metaphor and, therefore, takes the lazy route of uninformed comparison.

Each supercilious game-movie association, like those that appear most recently in criticism on Sucker Punch, builds on social assumptions that go beyond cliché into plain falsehood. (Full disclosure: I have not seen Sucker Punch, and that fact is irrelevant to this essay.) Some game comparisons are bound to be apt, given the nature of Sucker Punch, its creator (Zack Snyder), and his history. James Berardinelli (Reelviews) says, "As each of these tasks is performed, we are catapulted into bizarre video game-inspired scenarios in which a goal must be achieved." Other critics, such as Lisa Schwarzbaum (Entertainment Weekly), make similar proper comparisons. But the untrue notions of other critics include poor conjecture about what video games are like and what people who play them are like. Such critics lump every game and gamer into a category that likely disappeared, if it ever truly existed, when these critics were "pimply" and "adolescent"—as the Chicago Tribune mentions about some gamers. The marginalized geek exists much more commonly today as a straw man than a real person. Gamers of today are, instead, a diverse folk.

The lumping in doesn't stop with gamers, though. A.O. Scott (New York Times) lumps "video game platforms" among the materials, including drugs, you might need to construct Sucker Punch yourself. He also describes Babydoll and her cohorts, the central figures of Sucker Punch, as video game "avatars" and suggests that Scott Pilgrim vs. the World used "game logic" better as part of its narrative. Unfortunately for his mental construct, video games, their platforms, and their avatars are not all alike. Neither is game logic something that has a consistent definition. (Scott Pilgrim uses comic book methods more than video game ones, but the streams cross enough in modern expression that the point might be moot.) Further, good video games, especially good narrative games, are not cultural equivalents to poorly written or pandering action, fantasy, or sci-fi movies. The tendency for Hollywood to make bad movies based on toy and game intellectual property doesn't allow for a critical license to reverse the relationship. Bad movies have been made from good games. Bad games have been made from good movies. The gamut extends in both directions, with an awful lot of just plain mediocre filling its creamy center.

In a similar center, gamers are not all alike. John Anderson (Wall Street Journal) wrote, "The action sequences are interminable, the acting is a joke, but Sucker Punch is a movie for people who prefer video games and who may be playing them during the movie." Tom Charity (CNN) starts his negative piece with, "Zack Snyder evidently had an awesome idea for a video game." He sums up by saying the movie is "Schlock treatment for comatose gamers . . ." The implicit assumption, the condescension, here is that gamers not only have no taste, perhaps not even the capability of conscious discrimination that could lead to taste, but they also have no attention span. Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune) says, "Each time the female protagonist goes into her bump-and-grind, the routine is depicted as a video gamer's fantasy of violent combat against zombie Germans in World War I, or cyborgs, or dragons." Which video gamer? Who is he talking about? He's talking about his own stereotype, or what he imagines to be the archetypal gamer.

In a similar center, gamers are not all alike. John Anderson (Wall Street Journal) wrote, "The action sequences are interminable, the acting is a joke, but Sucker Punch is a movie for people who prefer video games and who may be playing them during the movie." Tom Charity (CNN) starts his negative piece with, "Zack Snyder evidently had an awesome idea for a video game." He sums up by saying the movie is "Schlock treatment for comatose gamers . . ." The implicit assumption, the condescension, here is that gamers not only have no taste, perhaps not even the capability of conscious discrimination that could lead to taste, but they also have no attention span. Michael Phillips (Chicago Tribune) says, "Each time the female protagonist goes into her bump-and-grind, the routine is depicted as a video gamer's fantasy of violent combat against zombie Germans in World War I, or cyborgs, or dragons." Which video gamer? Who is he talking about? He's talking about his own stereotype, or what he imagines to be the archetypal gamer.

This is akin to claiming poorly done romantic dramas are exactly like all romance genre fiction—a wide field with varying degrees of writing, some very good—implying that all such fiction is ill conceived and poorly executed from a storytelling standpoint. It goes further, like suggesting such "schlock" is only for 50-something spinsters who live romance vicariously through books. (My wife reads a little romance fiction.) It's similar to marginalizing fantasy genre fiction, relegating all such writing to the realm of B-movie fantasy "schlock" and the fodder to the "Dungeons & Dragons crowd" (1), meaning, really, dateless, basement-dwelling troglodytes who are best at intellectual masturbation. It's basing opinion on popular myth.

A. O. Scott has an impressive background in literature and criticism of storytelling. John Anderson is a respected critic of film who has a long list of impressive publications and associations. Michael Phillips is similar in reputation, and is even a host of the show At the Movies. (Once Siskel and Ebert and The Movies. Phillips filled in for Ebert for a long time, too.) A number of critics have similar backgrounds in literature or film, or both, and they're respected in their field. I'm forced, however, to wonder why they don't stick to their areas of expertise and, instead, resort to drawing tired analogies about something they, by the tone of their statements, obviously don't know enough but assume a lot about. Their remarks are as inappropriate and ill informed as I would be if I insinuated their mythmaking stems from most of them being born in the 60s or earlier. It doesn't.

This diatribe might seem to be rooted in my taking personal offense at the hollow categorization of games and gamers. But this isn't about being affronted. I'm not insulted. These writers have it wrong about games and gamers, and to be truly offended, a little part of you has to believe the offender is right. I don't believe the critics are correct. I believe they've let us down by making false comparisons and weak arguments based on stereotype and conjecture, revealing more about their own disdain for certain cultural elements, or willingness to appear disdainful, than their knowledge about games and movies, and game movies. That is, they failed to do their jobs.

(1) Michael Goldfarb (John McCain 2008 campaign) shows similar myth buy-in, saying back then, "It may be typical of the pro-Obama Dungeons & Dragons crowd to disparage a fellow countryman's memory of war from the comfort of mom's basement, but most Americans have the humility and gratitude to respect and learn from the memories of men who suffered on behalf of others." He later apologized, "If my comments caused any harm or hurt to the hard working Americans who play Dungeons & Dragons, I apologize. This campaign is committed to increasing the strength, constitution, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma scores of every American." Wired referred to the gaff as a "resort to '80s-era cultural stereotypes . . ." going on to say, " . . . once McCain masters the internet, we're confident he'll contemporize and start bashing video gamers instead." I'd have stuck with the first statement.

(1) Michael Goldfarb (John McCain 2008 campaign) shows similar myth buy-in, saying back then, "It may be typical of the pro-Obama Dungeons & Dragons crowd to disparage a fellow countryman's memory of war from the comfort of mom's basement, but most Americans have the humility and gratitude to respect and learn from the memories of men who suffered on behalf of others." He later apologized, "If my comments caused any harm or hurt to the hard working Americans who play Dungeons & Dragons, I apologize. This campaign is committed to increasing the strength, constitution, dexterity, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma scores of every American." Wired referred to the gaff as a "resort to '80s-era cultural stereotypes . . ." going on to say, " . . . once McCain masters the internet, we're confident he'll contemporize and start bashing video gamers instead." I'd have stuck with the first statement.

February 10, 2011

Visions Verbalized

Awhile back, talking about the littlest con, I said that you, as a game designer, need to be able to tell me who I am in your game, what I'm doing, and why. I said that's your elevator pitch. If you can't produce an elevator pitch, your idea isn't solid enough. This is true in relative ways for expressions in other media—novels, movies, comic books, and so on—but we're talking games here.

Awhile back, talking about the littlest con, I said that you, as a game designer, need to be able to tell me who I am in your game, what I'm doing, and why. I said that's your elevator pitch. If you can't produce an elevator pitch, your idea isn't solid enough. This is true in relative ways for expressions in other media—novels, movies, comic books, and so on—but we're talking games here.

All games rely on this initial expression to become all they can be. A lack of focus at such an early stage leads, at least, to wasted work as designers realize a game's scope needs narrowing. At worst, uncertain direction at the outset is a path of failure. Kitchen-sink design's best results are like World of Synnibarr—wonderfully schizophrenic but ultimately playable only as a novelty experience.

Putting the point succinctly, goal-oriented production can't occur smoothly without clear vision of the end. This little axiom is true no matter how small the design goal is.

Writing for D&D Insider requires that sort of directed attention. First contact for work on Dragon or Dungeon is, literally, the pitch. You have to sum up your idea neatly, showing you know your objective. Realizing that you're pitching to one very busy man (Steve Winter) puts more pressure on you to home in on your design goals. Fortunately for you, you aren't starting with a blank slate. Dungeons & Dragons, as a high-fantasy roleplaying game with a ton of history, provides a lot of context for the pitch. The problem in that framework is tightening your vision.

I actually learned the concept of the pitch long ago from the writer's guidelines for GURPS. Back then, the proposal process required you to write the sell text you thought should appear on the back cover of the book you were proposing. The assumption was, rightly, that the ability to summarize a potential product's contents clearly and succinctly shows you have needed focus. Doing it with attention-grabbing style shows you have skill.

Challenging your chops even further, try summing up your idea in one sentence. I call this the nanopitch. Back before Keith Baker's Eberron existed, the Dungeons & Dragons setting contest, which Keith won, required this. Every entry had to have such a summary statement. Wizards of the Coast called this synopsis "core ethos" in fine Gygaxian style. The whole initial proposal had to fill one page or less.

For those of you who are interested, here is a paraphrasing of what I understand was Keith's core ethos for Eberron.

For those of you who are interested, here is a paraphrasing of what I understand was Keith's core ethos for Eberron.

Raiders of the Lost Ark meets Lord of the Rings meets film noir.

This statement takes understood media icons and genres, and then it turns them into a succinct, clear, and apt description of Eberron. I'm hooked. Tell me more, Mister Baker.

For contrast, here are my core ethos statements from my three proposal submissions, with world names added to differentiate them.

Ancentynsis: A millennium ago, the Tempest of Fallen Stars cast its Curse across the land, but civilization has risen again in a savage time of new legends.

Shining Lands: The Nine Furies covet the world and the Radiant Host has decreed that mortals must overcome this evil alone.

Durbith: Infernal powers secretly rule a dying world, and heroes must struggle against this mysterious doom and the sinister truth behind it.

Parts of these summaries sound like aspects of the 4e cosmology or other settings. That's because these statements are too general, or because I worked and had influence on 4e. Through my current sensibilities, I see lots of other flaws in my proposals, but the weakest link is a core ethos that lacks the precision of Eberron's.

Looking at my setting proposals, my core ethos statements are weaker than Keith's is, for sure. All the core ethos statements I've seen, admitting I haven't seen that many, are. Although the whole initial proposal for a setting in the contest could have been be one full page, and I wasn't at Wizards at the time, I'm willing to bet that thousands of the over ten thousand proposals were eliminated right after the judge read the core ethos. I'd say that was especially true if your core ethos contained a semicolon or an em-dash, or any umlauts. But I digress.

If you're designing a whole game, rather than a supplement for an existing game, writing a nanopitch, elevator pitch, and sell text works as a good trial. But these tests only do their job if readers besides you really understand your idea from what you've written. Submitting to this honest evaluation can tell you if you've centered your attention enough.

Games such as Fiasco don't just appear out of someone's fevered imagination. (Okay, they might, but let's pretend they don't.) Although I don't know, I'm willing to say that Fiasco is likely an outgrowth of its designers knowing its genre and intended play style, at least in theory, from the start. Otherwise, it's impossible to believe the game could represent its apparent intent so well. A finished game of Fiasco really feels like you just watched or help create a Coen Brothers movie. The game I played felt a lot like Burn After Reading, complete with a slough of corpses created in third-act carnage.

The best games, regardless of intent or media, live up to the elevator pitch ideal. Mage the Ascension, as an off-the-cuff example, isn't merely a game about wizards and magic. It's a game about a war for reality wherein consciousness is reality. Mages manipulate the world within the confines of consciousness, personal (enlightened or not) and collective. Left 4 Dead, for another instance, is furious survival horror that needs little other narrative detail. It's intentionally visceral, allowing you to know the story and characters in the narrow context of desperate battle against long undead odds. Knowing details of the zombie infection doesn't deepen the experience. It's not the same as a zombie film or television show (or graphic novel), such as The Walking Dead, in which knowing and caring about the characters is required for a similar effect.

The best games, regardless of intent or media, live up to the elevator pitch ideal. Mage the Ascension, as an off-the-cuff example, isn't merely a game about wizards and magic. It's a game about a war for reality wherein consciousness is reality. Mages manipulate the world within the confines of consciousness, personal (enlightened or not) and collective. Left 4 Dead, for another instance, is furious survival horror that needs little other narrative detail. It's intentionally visceral, allowing you to know the story and characters in the narrow context of desperate battle against long undead odds. Knowing details of the zombie infection doesn't deepen the experience. It's not the same as a zombie film or television show (or graphic novel), such as The Walking Dead, in which knowing and caring about the characters is required for a similar effect.

Some games fail in some way to live up to what seems to be their own core ethos, although this might not affect whether the game is fun. A schism might occur between expectations and options. Fallout: New Vegas is an illustration of the point. Fallout is about post-apocalyptic survival and science-fantasy action, but it has always had a measure of silliness with its 1950s World of the Future taken to the breaking point. To me, that made Fallout 3 more than acceptable in its idiosyncrasies. The hardcore mode on New Vegas is fun for various reasons, but it fails to fit in well with the expectations Fallout's ethos sets forth. Put another way, in hardcore New Vegas I need to drink water or suffer penalties, and ammo has weight, but a human being I shoot in the face with a shotgun lives on to shoot back. It's weird.

This break between ethos and expression can also occur when a game breaks from its normal modes into unexpected, sometimes jarring, territory. Matt Sernett described his experience with the Afro Samurai videogame in such terms, saying the boss fights frequently required play styles the game had yet to require. That makes those fights frustrating, because despite the fact that you're supposed to be at least the second-best warrior in the Afro Samurai world, you have to learn new skills on the fly against the strongest opponent you've faced.

Fable 3's designers made a similar mistake when they changed the emote system. Fable 2's system wasn't the best, but at least it didn't try to force me to dance with shopkeepers to make friends or to burp when I wanted to make a rude gesture. (Fable 3 did better than earlier Fables, however, in how your actions influence those observing you.)

Fable 3's designers made a similar mistake when they changed the emote system. Fable 2's system wasn't the best, but at least it didn't try to force me to dance with shopkeepers to make friends or to burp when I wanted to make a rude gesture. (Fable 3 did better than earlier Fables, however, in how your actions influence those observing you.)

None of this is intended to suggest that a game shouldn't break from its normal modes on occasion. Experimentation with the expectations your game has created or integrated just needs to be done carefully. For instance, Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell Conviction contains a flashback that takes you out of hit-and-run stealth tactics and into a warzone. That said, the skills you learned earlier in the game still serve you well in this high-action scene.

Like Splinter Cell Conviction, countless games originate in existing intellectual property (IP), rather than creating a new one. More care has to be taken with existing IP. People coming to the game have expectations that the game designers can't influence, much less control. Case in point, it was unexpected that the Dresden Files RPG allowed me to be anything other than a mage or human, like Harry. My reaction has little to do with the quality of the game, which is good, and everything to do with my own previous interaction with the Dresden Files IP.

This point brings me back to Matt Weise's IP Verbs exercise, which my friend Wil Upchurch asked me to elaborate on. Matt Weise is a member of the of the Singapore-MIT Gambit Game Lab, and this is his idea, not mine. His IP verb exercise is mostly about living up to an audience's expectations of an IP, since the IP itself already defines numerous aspects of the game. Matt described the premise fittingly when he brought up how many James Bond games are about shooting rather than the subtler aspects of the Bond IP.

With the exercise, you still need to answer the who and why questions of the elevator pitch to round out your game. An IP might define these or allow for some surprising twists, but the meat of the task is coming up with what the player does in the game.

Compelling in an exercise I've seen is a mock design teams use of The Wizard of Oz. That story is about Dorothy, the heroine, traveling the Yellow Brick Road, befriending creatures along the way to gain help and ultimately escape the Wicked Witch of the West and return home to Kansas. She does so without much intentional violence. Considering all this, the team came up with verbs such as befriend, cooperate, escape, explore, fly, help, oppose, seek, talk, travel, trick, and so on. They also paired the verbs with nouns form the IP, and they came up with and game about action subtler than typical video game fighting.

Compelling in an exercise I've seen is a mock design teams use of The Wizard of Oz. That story is about Dorothy, the heroine, traveling the Yellow Brick Road, befriending creatures along the way to gain help and ultimately escape the Wicked Witch of the West and return home to Kansas. She does so without much intentional violence. Considering all this, the team came up with verbs such as befriend, cooperate, escape, explore, fly, help, oppose, seek, talk, travel, trick, and so on. They also paired the verbs with nouns form the IP, and they came up with and game about action subtler than typical video game fighting.

The team, led by Jeff McGann (Irrational Games) and Steve Graham (DSU game design faculty), decided that the player plays the flying monkeys, lackeys of the Wicked Witch of the West. You see, the monkeys are tired of serving the cruel sorceress, so they're engaging in a secret revolt. Their aim is to help Dorothy make it to Oz, foiling their mistress and ultimately leading to her demise. The hitch: They have to do all their helping without anyone growing wise to their trickery, especially the witch. Mollifying the witch, if she grows suspicious, and faking out Dorothy and her friends are part of the plan. Success means, ding-dong, the witch is dead and, whaddya know, the monkeys are free. That's what the team called The Monkey Business of Oz.

I'd play that game. The concept also lends itself to more than one media expression.

And that's the point of sharpening your design skills by honing you ability to crystallize your concepts. Ideas come in droves. The skill and willingness to extract the gold from the raw ore is the real magic. Then comes the ability to communicate your intent with those who can help you produce your idea. If you can make them see the gold by incisively directing their attention with a good pitch, you're well on your way.

February 4, 2011

The D&D Experience

Note: I've included Twitter handles for a lot of people, because I know a lot of you know these folks, just not by actual name.

A few of us from Critical-Hits were at D&D Experience this year. Matt Dukes (Vanir, or @direflail) was there as a civilian and regular ol' gamer representative. Shawn Merwin (@shawnmerwin) attended as a DM and writer. I went as a DM and administrator for the Ashes of Athas campaign. Dave Chalker (@DavetheGame) got trapped in DC on his way to the show, so he didn't make it. We missed him.

Lots of conventions, from PAX to Comicpalooza, have D&D games and organized play. None of them are like D&D Experience. This convention is about hardcore D&D gaming and D&D news. It's all D&D all the time on official channels. Players who come here come to play the game from sunup until the witching hour. When they're not playing, they're learning more about D&D from the experts.

I got in early in the afternoon on Wednesday, and I snagged my "Judges Kit." In it was my schedule, printed versions of the adventures I was running, an RPGA D&D shirt, and coolest of all, the upcoming Deluxe DM Screen. (See a little of it in the picture here; snag yours on or after February 15th.) I supplemented with a roll of Gaming Paper for maps, which I drew at the show.

I got in early in the afternoon on Wednesday, and I snagged my "Judges Kit." In it was my schedule, printed versions of the adventures I was running, an RPGA D&D shirt, and coolest of all, the upcoming Deluxe DM Screen. (See a little of it in the picture here; snag yours on or after February 15th.) I supplemented with a roll of Gaming Paper for maps, which I drew at the show.

Ashes of Athas

Earlier this year the Baldman—Dave Christ, who runs Baldman Games (@baldmangames) and D&D Experience, pants optional—involved me in this Dark Sun convention-only campaign. With the talented and enthusiastic Teos Abadia (@Alphastream) and Chad Brown, both of whom are also organized play vets, and the incorrigible Matt James (@matt_james_rpg), I helped create the opening chapter of a story-oriented campaign set on Athas.

The campaign takes a group of Veiled Alliance members and affiliates, the player characters, from Tyr to Altaruk and beyond. In Tyr, the alliance is in trouble, and rescuing it requires characters to save their last leader in an unusual way. When she's safe and in Altaruk, the trouble is just starting. It seems the alliance's enemies have big plans in the region and ancient magic to help them see that plot to fruition.

D&D Experience saw the first chapter played out, and other chapters should appear at Origins and Gen Con, among other shows. I was slated to run the adventures for this opening chapter most days of the convention—all day in most cases—and, boy, was it a pleasure. I blame that entirely on my players, for whom I feel extremely lucky.

One table had four thri-kreen characters alongside a dwarf. It's a good thing that dwarf had personality, because thri-kreen claws in every opening attack is murder. Another table had four halflings, with Shawn Merwin's knight among them, and one mul. The players in this "most obnoxious D&D party evar," quoting Shawn, took Athasian halfling foodie to another level. They made "drool saves" when they put some enemies down. (That was Shawn's idea. I blame him. Shawn's a great roleplayer—I hope to be a player at his table sometime.) Another group was an organized bounty hunter band known as Rough Trade. I use "band" here in two ways, because these roughnecks had a musical side that benefited them in play. Their leader is a dray bard with the nickname "Darling"—don't ask, because I don't know and don't want to.

It was cool to see the same scenario play out differently based on character choices. In one scene, the characters needed a wooden bowl, and every playgroup solved the problem in a unique way. The choices also earned players and groups differing story awards. One group captured all the crodlus in one encounter, while other parties killed the same crodlus. But, hey, that's what the D&D game is all about. It's also part of why running the same adventure for different groups can be so worthwhile. Try it if you have a chance.

It was cool to see the same scenario play out differently based on character choices. In one scene, the characters needed a wooden bowl, and every playgroup solved the problem in a unique way. The choices also earned players and groups differing story awards. One group captured all the crodlus in one encounter, while other parties killed the same crodlus. But, hey, that's what the D&D game is all about. It's also part of why running the same adventure for different groups can be so worthwhile. Try it if you have a chance.

DMing is rewarding, and it isn't hard. But, between you and me, I'm old. Running a game for nine hours straight each day told on me a little, especially when I didn't plan well for sustenance. Add to this that Matt James ran off with my maps one afternoon. (All was well, though, since I got to run the adventure for which I had maps for Shawn and his cohorts.) That's the extent of my hardship at the convention, meaning I had no real hardship.

I had a lot more fun. Besides, I also got extra loot, some of it prerelease, such as the new D&D Gamma World release Legion of Gold and the latest board game Wrath of Ashardalon. Both look awesome.

Insider Knowledge

Everything about D&D Experience is about rewarding dedicated players willing to come for half a week of D&D immersion. The seminars seem more lightly attended than, say, Gen Con. These smaller audiences are not only due to the concentrated nature of D&D Experience, but also because the gaming slots are back to back, all day, every day. Some people prefer to play and receive their news from the show's after-hours talk. The panels are all about playing the game, asking Wizards and other experts questions, or seeing upcoming products.

Speaking of upcoming products, Matt Dukes provided a blow-by-blow of the new products seminar. I already mentioned I got the newest Deluxe DM's Screen in my DM's kit. I'm particularly excited to see a couple products I helped with still on the schedule, namely Heroes of Shadow and The Shadowfell: Gloomwrought and Beyond. Both are about playing games set in or in touch with the Shadowfell. They also have some unique and exciting mechanics that add shadow power to your D&D game. Shadow power itself worms its way into other scenes, like an infection, tainting the use of other power sources. Few characters are pure shadow power users, like in the D&D editions of the past. I can't wait to see the community reaction to the pure shadow user I helped create.

Speaking of upcoming products, Matt Dukes provided a blow-by-blow of the new products seminar. I already mentioned I got the newest Deluxe DM's Screen in my DM's kit. I'm particularly excited to see a couple products I helped with still on the schedule, namely Heroes of Shadow and The Shadowfell: Gloomwrought and Beyond. Both are about playing games set in or in touch with the Shadowfell. They also have some unique and exciting mechanics that add shadow power to your D&D game. Shadow power itself worms its way into other scenes, like an infection, tainting the use of other power sources. Few characters are pure shadow power users, like in the D&D editions of the past. I can't wait to see the community reaction to the pure shadow user I helped create.

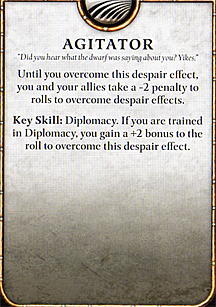

The Gloomwrought product is about the setting of and adventure in the Shadowfell. I had the privilege of developing and editing it, and it's creepy and scary in a number of ways, including mechanically. While the milieu and monsters are cool, one unique mechanical element I'm looking forward to seeing in use is the Despair Deck. It's a stack of cards that represent the negative effects the Shadowfell can have on player characters. A sample we received at the convention serves here as an illustration. (Dread Gazebo has more on the Despair Deck here.)

After Hours

Another great part of D&D Experience, especially since it's more concentrated D&D than Gen Con, is being able to meet and hang out with friends, new and old. (DMing also gains you friends, let me tell you.) For instance, I met the infamous Jerry "Dread Gazebo" LeNeave (@DreadGazebo) and discovered that Erik Nowak and I went to the same art school at the same time. He sold me art supplies, too. Since Fort Wayne is a smallish city, a lot of people stayed at the same hotel and went to the same watering holes. (My favorite is J K O'Donnell's—if you're in Fort Wayne, try it out.) It was easy to meet up and have fun, and I was thankful for that given my wholly unreliable phone.

I played a lot of after-hours games that were new to me, even if they aren't new releases. My first ever game of Dominion—against Liz Smith (@Dammit_Liz of w00tstock and etc.) and Tracy Hurley (@SarahDarkmagic) and another guy whose name I don't remember—saw me three points shy of the lead. (That's right Liz. Be ready next time.) I played Three Dragon Ante: Emperor's Gambit with new friends Jonathan Westmoreland (@EldritchReverie) and Brent DeVos. I don't know who won, I realize, but I think it was Brent. I also played a draft round of Magic with Ice Age cards, thanks to Matt James, with Stephen Radney-MacFarland (@NeoGrognard), Rob Schwalb (@rjschwalb), Erik Nowak (@Erik_Nowak), and James Auwaerter (up and coming D&D designer). Schwalb stomped us with his red burn deck—my black creature-control deck was a little slow.

Among these highlights was also Michael Robles's (@michaelrobles) Christmas at Ground Zero adventure for Gamma World, all rhymes all the time, at J K O'Donnell's. Matt Dukes played a doppelganger plant (?) named Optimus Gemini, Tracy Hurely ran a plastic engineered human named Barbie, and Matt James played an android cockroach whose name just drops the "roach" part of that last word. Greg Bilsland (@gregbilsland) played a cryokenetic radiation sentient cryostorage tank with a Russian accent. I forget its name, but it was looking for love. Dustin Snyder (@WolfStar76) took the part of a gelatinous winged mutant with very effective slimy powers and a warning not to fly over my character, Bam-Bam the Bang Ball, a radioactive exploding orb of fun that also served as Barbie's pet. R-rated gameplay might be a conservative description, and we killed Rudolph and Santa.

Among these highlights was also Michael Robles's (@michaelrobles) Christmas at Ground Zero adventure for Gamma World, all rhymes all the time, at J K O'Donnell's. Matt Dukes played a doppelganger plant (?) named Optimus Gemini, Tracy Hurely ran a plastic engineered human named Barbie, and Matt James played an android cockroach whose name just drops the "roach" part of that last word. Greg Bilsland (@gregbilsland) played a cryokenetic radiation sentient cryostorage tank with a Russian accent. I forget its name, but it was looking for love. Dustin Snyder (@WolfStar76) took the part of a gelatinous winged mutant with very effective slimy powers and a warning not to fly over my character, Bam-Bam the Bang Ball, a radioactive exploding orb of fun that also served as Barbie's pet. R-rated gameplay might be a conservative description, and we killed Rudolph and Santa.

Our hijinks sold Gamma World at least twice (to Jonathan and Brent, no less). Better than that, our hysterics attracted the attention of nongamer patrons at the bar who engaged us to see what we were doing. They thought the concept was neat, especially with reference to the collider and the Big Mistake. It led to a discussion of the possibility we actually exist in an alternate reality. Nongamers are weird!

Rob Bodine (one of synDCon's overlords, @GSLLC) was kind enough to include me in a Wrath of Ashardalon game, its pieces basically fresh out of the shrinkwrap. If you've played Castle Ravenloft, you've basically played Wrath of Ashardalon, and that's a good thing. If you've seen the quality of Castle Ravenloft, you understand the quality of Wrath of Ashardalon. The two games are compatible and mixable, and they're both sturdy and nice looking. Wrath of Ashardalon is also a good game to play with new friends, since you have time to chat and kid around more than a typical D&D game. Just so you know, Erik Nowak plays a mean paladin—you want him in that role. I also got to meet some new people, including Nate (surname unknown; @nullzone42).

Other than that, I had good talks with the likes of Shawn Merwin, Derek Guder (Gen Con general, @frequentbeef), Chris Tulach (@christulach), and others I've already mentioned—especially the Ashes of Athas team. Stephen Radney-MacFarland is definitely worth a second mention, as is Rough Trade (also part of Clan Beerbiter for you LFR peeps). Despite the recovery time, these shows are always worth the time just for the people. Gamers are fine folks, and so are the people who make our favorite games.

Escape From Chicago

I left the convention later than anyone I know. My flight departed from the airport at around 7 PM. Or it was supposed to. Snowpocalypse XLV was descending fast on the Midwest, and Chicago air control had us grounded for a while, clenching our teeth. But the plane took off, and I made my flight from Chicago to Seattle due to a convenient bout of Alpah Flux. I fear if I had missed that plane, I'd still be in the Windy City looking for help from Snake Pliskin. Does he have skis? More important, can he see in a whiteout?

I left the convention later than anyone I know. My flight departed from the airport at around 7 PM. Or it was supposed to. Snowpocalypse XLV was descending fast on the Midwest, and Chicago air control had us grounded for a while, clenching our teeth. But the plane took off, and I made my flight from Chicago to Seattle due to a convenient bout of Alpah Flux. I fear if I had missed that plane, I'd still be in the Windy City looking for help from Snake Pliskin. Does he have skis? More important, can he see in a whiteout?

January 13, 2011

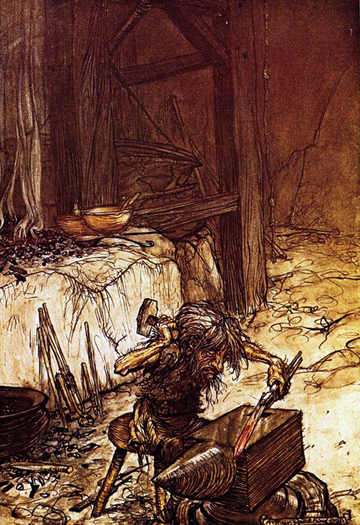

Into the Unknown

In roleplaying games, the D&D game especially, characters delve into mysteries that surround them. They might wish to bring light into the darkness of the world. Curiosity could drive them. A desire for wealth and fame might be enough motivation. Whatever the case, adventurers go in search of the unknown.

In roleplaying games, the D&D game especially, characters delve into mysteries that surround them. They might wish to bring light into the darkness of the world. Curiosity could drive them. A desire for wealth and fame might be enough motivation. Whatever the case, adventurers go in search of the unknown.

Discovery is a process. It requires motivation, followed by exploration and a willingness to keep going despite setbacks. In games, it also requires that the truth is discoverable. Someone has to know the facts, or something has to exist to help lead seekers to the situation's reality.

Mysteries must have answers in all roleplaying games. At least, the secrets the players wish for their characters to uncover should have some means of being laid bare. That means the DM, at least, has to know, or have an idea, where a path of exploration leads. In the case of published work, the designers should know such answers and, more important, reveal them.

We designers fail to do that sometimes, however. In books, we make statements such as:

Iyraclea is the mistress of the Great Glacier. From her realm beneath the ice she spell-snatches young, vigorous mages for some unknown but doubtless sinister purpose. Iyraclea worships Auril the Frostmaiden and commands magic of awesome power . . . . Few see her castle of sculpted ice and live to tell the tale.

Half a century before the start of the Last War, an unknown evil infected the lycanthropes of the Towering Wood, stirring them to violence and driving them east to wreak chaos in settled lands.

I've been guilty of it:

Known also as the Wood of Dark Trees, this dense jungle is home to all sorts of dangerous creatures. The animate and malevolent trees from which the forest gets its name are numerous, as are venomous flying snakes. A pair of chimeras with black dragon heads lives deep in the forest, lairing not far from the Mound of the Sleepless and attacking any who approach. What the chimeras guard is unknown.

My sensibilities have changed over time. Once, I might have tolerated such vagueness in my own game writing. Now I see this type of ambiguity as a disservice to DMs and players. It's unhelpful at best, and maybe even lazy at worst.

I know the reasons for leaving narrative elements undefined. We primarily tell ourselves that we're leaving space for the DM to create, or we're avoiding imposing our "official" ideas on users. Maybe we're even evading canon bloat. We're protecting DMs, in case the players read "the truth" in the campaign guide. Further, our blank space is a call to design for those who use our products. Occasionally, the "unknown" is the subject of another product such as a novel or adventure. To me, this situation is even weaker than the aforementioned reasons. It also misses a chance a cross promotion, but I digress.

All those rationalizations are malarkey.

This sort of design gap does little to live up to any ideal of leaving imagination space for the consumer. What it really does is force users, whether DMs or players, to work for the answer without any help. Designers fail even to give hooks for ideas. To me, this unknown is unacceptable.

A designer should—no, must——provide inspiration. That means the "unknown" should be filled with clues, hints, and rumors. What do ordinary folks think? If common people know nothing of the mystery, what do those in the know believe or imagine? If no one really knows, what might investigation uncover?

It's okay for a designer to go ahead and reveal the truth, too. Tell it like it is. Even if no one on Faerûn knows the facts of the matter, it's fine if the DM does. In fact, that's essential. It's easier on the DM if he or she has a list of options to start from.

Although I've made some to-do over the power of canon and official material to impose an outside reality on what is really a personal game, I still believe it's a designer's job to give possible parameters rather than wide-open space. Rumors and sagely (or not) opinions give fodder for the imagination. A situation's overarching truth does the same, but gives fewer choices and can make some users feel restricted.

Even then, a user is always free to ignore a designer's clues or story. Such ideas exist only as inspiration. Their absence, however, is the absence of such inspiration, the refusal to offer a helping hand. It's less than a designer can and should do.

Even then, a user is always free to ignore a designer's clues or story. Such ideas exist only as inspiration. Their absence, however, is the absence of such inspiration, the refusal to offer a helping hand. It's less than a designer can and should do.

Besides, rumor and speculation, as well as the counsel of the learned and discoveries of the adventurous, give the world some semblance of life. Normal people always wonder and make wild guesses about the scary and the strange. Sages constantly formulate theories, sometimes based on little more than common conjecture. Explorers go on to uncover evidence, offering further suggestions to the actuality of a given enigma.

For instance, if a dragon lives on a mountain, someone or something knows it's there, knows it's name, and knows what it's doing. It's a failure to give the dragon no name and driving force. Think about what The Hobbit might have been like if old Smaug was just some red dragon with an unknown lair and purpose in the area of the Lonely Mountain. If no one has survived an encounter with our supposedly unknown, mountain-dwelling dragon, the adventuring party who overheard dragonblooded kobolds of the lower slopes referring to the "great gray god Yarzog" is enough to hang an entire adventure on. That reveal also takes a sentence of space.

Although hints or full reveals are possibilities, hints and clues win out over solid facts. Such revelations give the DM something to work with while protecting players from too much truth. If a player reads the possibilities, it's little different than the character hearing rumors. Players can't know what their DM picks from among possibilities until the adventure is on.

This whole essay forms a generality that, of course, has exceptions. Some truths are too big to impose on the whole audience. A few are so massive that rumors are simply prevailing currents of theory in a sea of possibilities.

One such instance is the truth of what happened in the Mournland of Eberron, something James Wyatt rightly vowed never to decide or reveal in any venue. That some cataclysmic magical force laid waste to the fey beauty of Cyre is obvious. Where that force came from, and whether it can happen again, is a matter of wild guesswork in Khorvaire. So chilling is this unknown that it ended a continent-wide war. Still, the Eberron books contain numerous theories to the Mournland's cause. Any or none of these might be true in a given campaign. (I blame House Cannith.)

And that's the point. Designers need to give clear idea hooks when a definitive truth cannot or should not be revealed. In a setting or adventure, the truly unknown is ultimately a place no adventurer goes.

December 9, 2010

On Writing

I stole that title from Stephen King, but that's okay, because I disclosed it and this is not a memoir of the craft. Well, it might be a little memoirish, but that's only to make you believe that I might, perhaps, know something about the subject. Given evidence in the marketplace, I have to believe that the fact I have been published offers little proof.

I stole that title from Stephen King, but that's okay, because I disclosed it and this is not a memoir of the craft. Well, it might be a little memoirish, but that's only to make you believe that I might, perhaps, know something about the subject. Given evidence in the marketplace, I have to believe that the fact I have been published offers little proof.

More than a few folks have asked me for advice on writing. I don't know why. I have edited and written, with mixed success at both, for publication and pleasure. Like I said, that doesn't prove anything. What I can say is that writing isn't easy. It takes courage and skill and patience, and a good editor always helps.

That's why I owe a lot to my time as an editor. While I was one, I learned more about writing than I imagined possible. My writing improved immeasurably from skills and training I gained. I owe a lot to my mentor, the immortal Kim Mohan, and experienced colleagues such as Cal Moore, Jennifer Clarke-Wilkes, and Jeremy Crawford. (All of these folks are better editors than I am.)

If you can't edit the work of others, though, you need to read and write, read and write. And rewrite . . . and rewrite. Give your work an unkind eye. Love nothing you write so much that it must survive. Slice and rearrange to make sure you're saying what you mean and want to say in as clear a manner as possible. (This is all assuming you aren't writing an experimental novella or poetry.) Achieve closure within your deadline because, if you're like numerous authors and artists I know, you might never truly finish tinkering.

Paper Tigers

When you write, or most likely rewrite, keep an eye out for usage issues that might weaken your bold statements and sure sentences. These hobgoblins not only make your prose look flabby, but they also make it seem like you are less than sure of what you're saying. Sometimes they just look like mistakes, which can soften your reception either from your editor or from your audience.

Issues described here are very common in the writing I've seen over the span of my short career. Most of them also appeared in my writing at one time or another. Eliminate them and you're a step ahead of the pack, especially when submitting to Wizards of the Coast. Also, your editors might just learn to like you and say so to the right people. If you don't submit to another party, then it's your readers who might just thank you.

Pronoun Problems

Their, they, and them see an awful lot of use these days, and they appear without warrant. I've had someone tell me, his editor, that the use of a plural pronoun (they) with a singular subject (someone) is correct, because a university professor said it is okay. News flash: If that professor ain't* an English teacher, he or she is not to be trusted. If he or she is an English professor, for shame. In either case, he or she is wrong. Following that advice makes your usage look amateurish, because pronoun misuse is a common mistake among amateurs. (We misuse pronouns all the time when we speak, which is probably the source of confusion.) It's simple, really. If you have a singular subject, use a singular pronoun.

In doing so, you can also avoid confusion that pronouns can cause. Imprecise usage can harm clarity in your work. Take this passage:

Psionic seers in the Gray felt the presence of many minds. They appeared as only shadows, a sort of interference in the psychic ether for as long as most of them could remember. It was not until certain psions realized these were living minds passing through that they tried to bring them out. They set up a teleportation circle in the location that corresponded to where the Gnomes wanted to appear in The Land Within the Wind. Setting a psychic anchor point, they focused on the circle. What began to spill out was shocking, and immediately killed the summoners.

When you read that, are you always sure what or whom each "they" or "them" is referring to? Context helps understanding, sure, but the passage lacks precision. Careful usage can clear that problem right up.

* I recognize that language evolves and is evolving. We aren't, however, at that spot in time when a plural pronoun has become an acceptable replacement for a singular one. But, oh, how I long for the death of whom.

There's No Place

There's No PlaceSpeaking of their, a similar sound starts a bunch of sentences I've seen in my days. There is no way you can start a statement with "there is" without weakening it. See? The quote "There's no place like home." has less punch and more flab than "No place is like home." The latter version pounds the point home better.

My example is less than ideal, however, because it's a piece of dialog. Dialog is different. People have all sorts of quirks in speaking that are acceptable when writing dialog. When your statement is other than dialog, though, it's best to evict "there is" from your prose when you can. Minimizing your usage of "there is" can help you habitually make stronger sentences.

Future Upon Us

Especially in game or scenario writing, so much action hinges on preceding actions. That places scads of action in the future, a state of uncertain possibility. The normal tendency for writing about the future is to say something "will" happen. It's true. Avoid using "will" anyway. It's weak and hedges the excitement.

If the orcs attack when they spot strangers, just say so. The orcs attack when they spot strangers. Easy. Adding "will" before "attack" in that statement is like adding a couple spoonfuls of sugar to your ice cream. It gains you and your consumers, the readers, nothing except empty calories.

Sometimes it's necessary to use the word "will." It's clear when that's the case, because trying to go without it hurts your head. Even then, though, other words can suffice. Skeptical? Look back to where I wrote about your readers thanking you.

Pointless Passivity

I have no idea why, but numerous writers use passive voice. (I see and hear it most commonly in the news, making me wonder if it's some sort of journalistic style.) Do you want to sound passive? No, you don't! You want to sound bold and sure. A giveaway that you might be using passive voice is the word "by" in your sentence.

Say you want to tell me the town was razed by goblins. Well, the important part of that statement sounds like someone on medication said it—the kind of drug that induces drowsiness and the munchies. Goblins razed the town! Now that's a fit and trim statement worthy of an exclamation point. It also sounds like a frantic peasant might have said it, which is the point.

Samurai Way

Samurai WayIt is said that it's better to ask for forgiveness than it is to ask permission. I say it's better, especially in rules prose, to avoid language that implies permission. Find the word "may" in your prose, and kill it dead when "might" or "can" makes a fine replacement. The reasoning here is precision in communication.

You can tell the people it may rain on Saturday, but they might wonder who you are to allow it. Tell them it might rain on Saturday, and they understand immediately that precipitation is a matter of chance. Similarly, a rule that says you may draw a card at the start of your turn implies permission and, perhaps, other factors. If a player can draw a card, just say he or she can (not to be confused with "must").

Weak Links

We, especially when speaking, hedge our language with modifiers. Some modifiers imply exceptions to generalities, while others are editorial. In writing, such modifiers serve poorly. They weaken your prose, making it sound wishy-washy or strange rather than inclusive or insightful.

Weak modifiers include words and phrases such as "usually", "relatively", "often", "tend to", "a bit", and so on. Everyone can spot a generality, so you need not hedge it with weak modifiers. If elves typically dance among the branches at sunset, you can just say they dance among the branches at sunset. No one needs the word typically. (Sorry, typically, but it's true.) Generalities imply exceptions.

Unfortunately, editorial modifiers make a statement sound meaningful in ways that are imprecise or unintended. In that last sentence what was unfortunate and who was it unfortunate for? Unless the modifier has actual meaning for the reader, it's best left out. These words, even "even", can be dropped with no real change in meaning or implication.

In Conclusion

All of what I've written here is just to make you write with a critical eye. Just don't sweat it too much in the first draft. Put your ideas down, and then rework them. Also, ignore the rules when you intentionally want to break them. Just make sure you mean it.

You might make mistakes. So do all other writers, including me. Since I edit this blog myself, with some help, and my self-imposed writing window for it is small, I probably left a few issues in this essay. It's not about perfection so much as saying with clarity and grace what you intend to say. I, for one, wish you great success.

Aside: One of the best books, evar, on the subject of grammar is Woe is I. Check it out or buy one. If you're an aspiring writer, you're unlikely to regret it. You might also be surprised at some of the elements of style that are falsely foisted upon us. You'll be ending your sentences with prepositions guilt-free in no time.

Special Thanks: Gratitude to Seamus Corbett (icu_seamus from Twitter) for allowing me to use a passage from his post (as the Opportunist) "Races of Athas – Gnomes and Shardminds" on RPG Musings. Seamus asked me about writing, and our correspondence inspired this blog post. Plus, Seamus is a cool name.

November 18, 2010

One-Hour Game Design

A year ago, I went to Nanocon and made friends with the illustrious Richard Dansky. On Friday evening, we were a between commitments, and we were amused at the Dakota State University game design program's promotional literature. We also stumbled on some loose dice and game pieces. We decided to make a game in an hour, then playtest it during the rest of the convention. The result is Rush at Zeta Mu Beta. Here are the rules. Enjoy!

Rush At Zeta Mu Beta

A game by Richard Dansky and Chris Sims

It's rush week at DSU, and the frosh zombies are eager to pledge Zeta Mu Beta. To do so, they'll need to bring back the Homecoming Princess to their lair at the Computing Center and turn her into one of the living dead. But the Jocks of I Phelta Thi have no use for zombie nerds! They're dead set on capturing the Zombie Prom Princess, taking her back to the Field House, and giving her a sharp blow to the brainpan. The race is on. May the most ruthless team win!

Players

2 or 4: One zombie and one jock, or a pair of zombies and a pair of jocks. Zombies are on one team. Jocks are on the other.

Supplies

SuppliesYou need a few items to play.

• A board, which is the 16 x 14 map of Dakota State University from the "Super Trojan Master 2" brochure by Kiel "MagicMouse" Mutschelknaus.

• Dice, including one twenty-sided die (d20) and one four-sided die (d4) per player. You also need a pile of six-sided dice (d6) to represent Mysterious Floating Cubes. More on those later.

• Playing pieces, including a chess knight for each player's playing piece—or a chess knight and chess rook, one for each allied player. You also need a chess queen for each team's Princess, and a gaggle of chess pawns for Minions. (More on those later.) Each player or team should use playing pieces of differing colors. You can use something other than chess pieces, as long as it's clear which team and player a given piece belongs to.

Setup

Lay out the board. Players place their playing pieces inside their team's base. The jock base is the field house (#20). Zombies have their base in the computer lab (#5). Each team places its Princess on the Cloud, which is in the upper left corner of the map and has a princess on it.

The Cloud

The Cloud is for Princesses and losers. You can't move onto it unless you fall in combat, Further, you can't grab a Princess to carry her while you and she are on the Cloud.

Playing the Game

Game play is divided into rounds during which each player takes a turn.

• Your goal is to capture the enemy team's Princess and take her back to your base. Succeed, and your team wins the game.

• At the start of each round, each player rolls a d20. (Reroll ties to determine the order of tied players.) The player who rolls the highest result takes his or her turn first. Then other players take turns in descending order, highest d20 result to lowest result. Once everyone has had a turn during a round, a new round begins.

• On your turn, do the following in order.

1) If you're on the Cloud, return to your base. See also Mysterious Floating Cubes.

2) Roll a d20. Place the enemy team's Princess on the board location that has the number corresponding to the roll result.

2) Roll a d20. Place the enemy team's Princess on the board location that has the number corresponding to the roll result.

If this result lands the Princess in a space that an enemy player occupies, then she instead moves to the Cloud for that turn. (Minions aren't players.)

3) Roll a d4. You have that number of movement points for this turn.

4) Spend your movement points.

The board is divided into blocks and buildings. You must spend 1 movement point to move one block— about the distance equal to the size of the residential block just above the buildings 7 and 8 on the map. Moving into or out of a building also costs you 1 point. You need not spend all your movement points.

Alternative Movement

For more exact movement, each movement point can be spent to move one inch. Make this easy by including a small ruler or marked popsicle stick among your supplies.

If you move into a building or space that contains the enemy team's Princess, you can pick her up and begin carrying her. See Carrying an Enemy Princess.

If you elect to pick up a Mysterious Floating Cube, you must end your movement to do so. Picking up the Mysterious Floating Cube also ends your turn. You cannot pick up a Mysterious Floating Cube from the same space on your next turn. See Mysterious Floating Cubes.

If you land on a space that an enemy player or Minion occupies, you must engage in combat. See Combat.

Carrying an Enemy Princess

An enemy Princess isn't too heavy for a jock or zombie, but she struggles and sometimes escapes. Some aspects of the action change while you're carrying an enemy Princess.

• When you begin carrying an enemy Princess, you lose all but 1 movement point you had remaining, if any.

• You gain 1d4 – 2 movement points per turn, instead of 1d4, with a minimum result of 1.

• If a teammate wishes to begin carrying the enemy Princess from a space you're carrying the enemy Princess in, you decide whether to relay the Princess to your teammate.

• You can't pick up Mysterious Floating Cubes.

• At any time, you can choose to release the Princess you're carrying. She then resumes moving according to the normal turn order.

Mysterious Floating Cubes

Whenever you pick up a Mysterious Floating Cube, grab a d6 from the pile. Keep it until you use it. You can use a Mysterious Floating Cube in the following ways.

• Roll the d6, and add the result to any combat roll.

• Roll the d6, and add or subtract the result from any d20 roll the enemy team makes to move a Princess during the normal turn order.

• Allow your team's Princess to flee an opposing player who is carrying her. Roll the d6. The result is the number of movement points you can spend to move the enemy player carrying your team's Princess away from his or her base. At the end of the movement, that player is still carrying your Princess.

• Discard the d6 back to the pile to allow a teammate that starts his or her turn on the Cloud to roll a d20 and reappear on the board location that has the number corresponding to the die roll result rather than in your base.

Combat

CombatWhenever a player moves into a space an enemy player or Minion (see Minions) occupies, they fight. Here's how.

1) The player who moved into the space (the attacker) chooses a single target.

2) Each team's members declare if they're using Mysterious Floating Cubes, and how many. You can't spend a Mysterious Floating Cube to aid a Minion.

3) The attacker rolls a d20 plus any added Mysterious Floating Cubes, and the defender does the same.

4) The highest result wins. The losing player is sent to the Cloud. Minions are instead removed from play.

5) The winner places a pawn of his of his or her team's color on the space to represent a new Minion.

6) If the loser is carrying the Princess, she is freed but remains in that space. She then resumes moving according to the normal turn order.

5) Combat continues until one player remains in the space or Minions from only one team remain in the space.

Minions

Minions are lesser members of your team. They aren't players, but they can be useful. Here's how.

• If an enemy player shares a Minion's space, he or she must engage that Minion in combat.

• If Minions of opposing sides share the same space, they must fight until only one side's Minions remain.

• Whenever you receive a result of 1 for movement points, you also gain 1 extra movement point that you must spend to move a Minion.

• Minions can't pick up or use Mysterious Floating Cubes.

• Minions can't carry a Princess.

Winning

If you deliver the enemy Princess to your base, you win. The game is over.

The Point

I carried on the tradition of quick game concepting, or tried to, by challenging folks to do the same at this past Nanocon. They came up with another game, based on the same board and materials, but about graduating from DSU with the most credits while maintaining a happiness score. Opposing players try to whittle away at your happines.

Like the IP verb challenge I described in my last column, the test of using found materials and a time limit can really focus your creativity. Try it.

While you're at it, take a little challenge I have up this week on Roll, the Critical-Hits Tumblog. You just might win something. Check it out.

November 11, 2010

The Littlest Con

Madison, South Dakota might seem like a typical small Midwestern town. In some ways it is. But it's also the home of a Dakota State University and the school's Computer Game Design program. The DSU Gaming Club puts on a gaming shindig every year, and this legendary event is known as Nanocon.

Madison, South Dakota might seem like a typical small Midwestern town. In some ways it is. But it's also the home of a Dakota State University and the school's Computer Game Design program. The DSU Gaming Club puts on a gaming shindig every year, and this legendary event is known as Nanocon.

Nanocon isn't just a gathering to facilitate gaming of all types, which it does. It's also an educational event for the students at DSU. I was invited last year as a representative for Wizards of the Coast, among such design luminaries as the wise and skilled Jeff Tidball (a freelancer for Fantasy Flight, Atlas Games, and countless others) and the incorrigible cad Richard Dansky (White Wolf, Red Storm Entertainment, and novelist responsible for Firefly Rain). It was a great time, and I must have done something right, because they invited me back.

This year, the roster was filled with a few more experts, such as:

• Jeff Tidball was back, bringing with him a playtest version of a board game based on the well-known RPG [name redacted]. I was lucky enough to play the prototype. To me, Jeff's version captured the essence of the RPG better than the original did at times. Sure, like Jeff himself said, there were no intense roleplaying moments, but it as great themed fun. Perhaps we'll revisit it when the game is released and my NDA no longer applies.

• Jeff McGann, lately of Red Storm but on his way to Irrational Games and work on Bioshock Infinite. Jeff knows a thing or a thousand about the "hellish world" AAA game design. Primary in my mind, as a designer of D&D, is his take on accessibility or lack thereof. Your game has to let people in, and if it doesn't, it won't matter how cool the second act is. Too few people will see that act. D&D has lacked real accessibility for long enough that the problem transcends editions. Maybe the new red box helps, but I don't think Essentials does. My point here is that most D&D players are inducted into the game without having to climb the complexity curve alone. Maybe more on that later.

• Matthew Weise of the Singapore-MIT Gambit Game Lab, researcher on game history with emphasis on Metal Gear Solid, zombies, and first-person RPGs. As a fan of stealth games, I appreciated Matt's analysis of the Metal Gear franchise. See Game Verbiage below for more on Matt.

• Matthew Weise of the Singapore-MIT Gambit Game Lab, researcher on game history with emphasis on Metal Gear Solid, zombies, and first-person RPGs. As a fan of stealth games, I appreciated Matt's analysis of the Metal Gear franchise. See Game Verbiage below for more on Matt.

• Clara Fernandez, also of the Singapore-MIT Gambit Game Lab, is a researcher on adventure games, puzzle design, and dream logic in games, as well as stories in simulated environments. Maybe it's obvious to others how puzzle design for a game is so much like overall adventure design, but I found that focus insightful. Puzzles have to provide enough information and hooks to keep players moving forward and satisfied with that progress, otherwise frustration sets in. Without a social reason to continue investing, most players just quit. Our adventures need to do the same while providing enough "imagination space" to allow DMs and players to personalize the experience. I think this is what modern D&D adventures lack, as Mike Shea has intimated.

• Kevin Rohan, the Content Director for Silver Gryphon Games. He also knows how to mix genres in Savage Worlds. As a player of Grover, mean with a pair of .44 revolvers, in Kevin's "Fist Full of Muppets" scenario, I should know. Kevin and I also gave a presentation about sandbox adventure design, and it was pretty cool. Try to create a scenario with a nonlinear progression for the proactive player characters. Then include villains that plan intelligently and move forward. The characters have to thwart the villain's agenda, or meet their own goals, while the antagonists do the same. It's a lot more interesting than monsters that wait to be killed in a site that changes only when PCs appear, let me tell you.

Back to School