Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

September 5, 2025

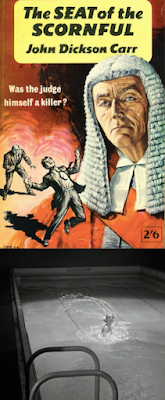

An unexpected book-movie connection: Cat People and John Dickson Carr

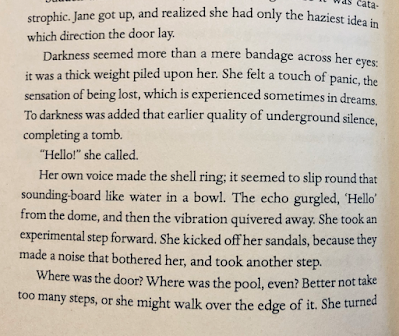

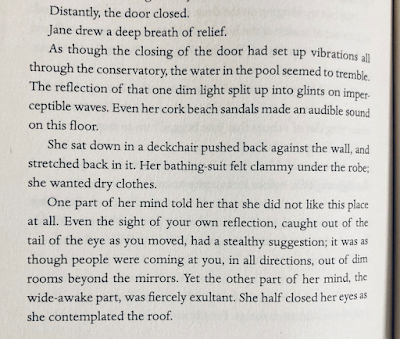

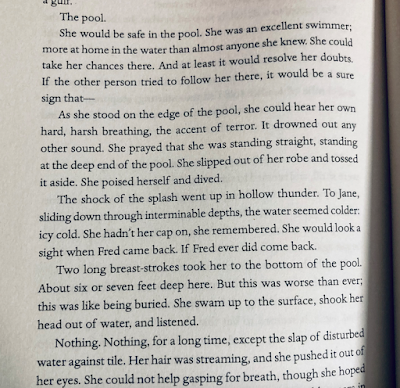

Most serious horror-film buffs will be familiar with the swimming-pool scene from the 1942 film Cat People – famous for its use of the power of suggestion, and a classic example of producer Val Lewton’s moody, abstract approach to horror (the scene has a woman being menaced by an unseen presence during a late-night swim, while we think we see something leopard-like amidst the dark shadows on the wall around the pool area). During my recent immersion in the work of John Dickson Carr, I realised that the Cat People scene may have been partly inspired by a creepy passage in Carr’s 1941 novel The Seat of the Scornful (also known as Death Turns the Tables).  The passage has a young woman named Jane who finds herself locked in the indoor-swimming-pool section of a hotel basement late at night… then the lights go out, and she thinks she is being stalked by someone or something in the darkness. The writing isn’t too elaborate, but there is something very vivid about the setting (a twilight zone located within an otherwise plush non-threatening space) and the imagery, with the water casting shadows on the wall and the unsettling acoustics.

The passage has a young woman named Jane who finds herself locked in the indoor-swimming-pool section of a hotel basement late at night… then the lights go out, and she thinks she is being stalked by someone or something in the darkness. The writing isn’t too elaborate, but there is something very vivid about the setting (a twilight zone located within an otherwise plush non-threatening space) and the imagery, with the water casting shadows on the wall and the unsettling acoustics.

As discussed here before, Carr was one of the giants of Golden Age crime fiction – nearly as popular as Agatha Christie at the time – and this book came out just a few months before Cat People went into production in early 1942. So it’s very plausible that Cat People screenwriter DeWitt Bodeen had read it. A couple of short excerpts are below.

(The book itself? Highly recommended as an example of one of Carr’s non-impossible-crime mysteries; in fact, it seems obvious almost from the start that only one person could have committed the murder in question – but of course things don’t turn out to be that straightforward. The swimming-pool scene isn't central to the narrative, by the way - it's a bit of a red herring, if you can expect a red herring in a hotel pool.)

(A post about Curse of the Cat People - a sequel that is very different from Lewton's other horror films - is here)

September 1, 2025

Murder and romance in a military hospital: on Green for Danger

Continuing with capsule reviews of Golden Age crime fiction. Yesterday I finished Christianna Brand’s 1944 military-hospital mystery Green for Danger (it was made into a popular film too, starring Trevor Howard and Alastair Sim among others). This is a solid, well-crafted whodunit – which is impressive when you consider that there are only six serious suspects, all doctors and nurses involved in a pre-surgery procedure that goes very wrong. (And that’s followed by a second death, which is much more clearly a murder.) So here is a small pool of characters, and some of the book’s humour comes from the way in which they sit around chatting with each other (often in the stiff-upper-lip British way) about which of them might be guilty. I can see Green for Danger not working for some readers, especially crime-writing fans who want regular, fast-paced thrills. Much of this narrative, and especially the first 40-50 pages where the characters are being established, has a romantic-soap-opera-ish quality to it: being about the sometimes-complicated interrelationships between these men and women (two of whom are officially engaged to each other, but there’s much other flirtation going on) – and while some of this is important to the mystery, it can make the book meander in places.

Continuing with capsule reviews of Golden Age crime fiction. Yesterday I finished Christianna Brand’s 1944 military-hospital mystery Green for Danger (it was made into a popular film too, starring Trevor Howard and Alastair Sim among others). This is a solid, well-crafted whodunit – which is impressive when you consider that there are only six serious suspects, all doctors and nurses involved in a pre-surgery procedure that goes very wrong. (And that’s followed by a second death, which is much more clearly a murder.) So here is a small pool of characters, and some of the book’s humour comes from the way in which they sit around chatting with each other (often in the stiff-upper-lip British way) about which of them might be guilty. I can see Green for Danger not working for some readers, especially crime-writing fans who want regular, fast-paced thrills. Much of this narrative, and especially the first 40-50 pages where the characters are being established, has a romantic-soap-opera-ish quality to it: being about the sometimes-complicated interrelationships between these men and women (two of whom are officially engaged to each other, but there’s much other flirtation going on) – and while some of this is important to the mystery, it can make the book meander in places. But on the whole, I liked it very much. There are a couple of good, well-placed red herrings, and some fine sociological detailing of wartime England - about life in a time and place where flippant or hedonistic behaviour can become a way of dealing with unpredictable horrors. This isn’t quite a M*A*S*H* or Catch-22 as army-hospital dark comedies go, but it is irreverent in its way. And strangely moving at times. (Also you learn a decent amount about operating-theatre procedures of the era.)

August 29, 2025

Carr, Christie and others: about a few more Golden Age crime novels

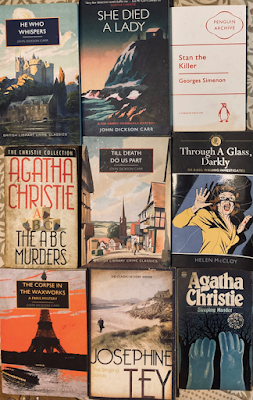

“Reader’s block” is something that has afflicted me a lot in recent years – some of it having to do with guilt about reading other things when I’m supposed to be concentrating on my own book (and also, an increasing fatigue about doing the sorts of long book reviews that I once enjoyed writing). But one almost fool-proof way of emerging from this is to bury myself in Golden Age crime fiction. I have written a few posts already about my encounters with John Dickson Carr, Ellery Queen, Helen McCloy, Stanley Ellin, Edward Hoch, Josephine Tey and others, in addition to the novellas and short stories in enormous crime anthologies edited by Otto Penzler – but here is a brief update post. A few mystery novels from that era that I have recently read (or reread):  First-time read: He Who Whispers (by John Dickson Carr)

First-time read: He Who Whispers (by John Dickson Carr)

I have been reading a lot of JDC, partly because the British Library Crime Classics editions have made his work a little more easily available than it used to be. He Who Whispers has quickly become one of my favourite Carr novels, despite my having come to it with very high expectations (because of its reputation among crime-writing experts).

The murder here – the stabbing of a man who was alone at the top of an inaccessible tower that was being watched from all sides – is one of Carr’s most intriguing “locked-room” or “impossible-crime” scenarios; but there is a lot else going on. There is the central character Fay Seton, one of the most mysterious of Carr’s doomed women (or femme fatales who may not be femme fatales); there is the hint of something supernatural afoot, which Carr was always so good at suggesting (before giving us the purely rational explanation); there is a second attempted murder which is almost as puzzling; and there are some fine passages such as one in a London subway train where two characters get together and exchange vital information (giving us, the readers, a firmer grasp on what is going on) while in the background the conductor at regular intervals calls out the name of each train station, and we just *know* that they are going to end up missing the vital stop that they must get off at.

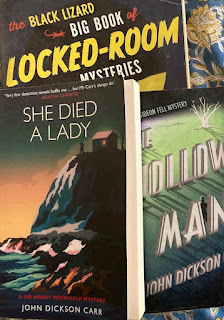

Re-read: She Died a Lady (by Carr)

I have alluded to this one before, but it’s difficult to properly discuss it without giving away something essential. So for now I’ll just say that 1) it is probably my favourite Carr novel, 2) that it held up equally well on a second read, and 3) it includes another “impossible crime” (involving inexplicable footprints) that is hard to work out.

Also that (no spoiler) I absolutely love the little trick he plays at the end of the book, a trick that is comparable in some ways to what Agatha Christie did in arguably her most famous mystery – but this one is subtler; it isn’t as dramatic or as gasp-inducing as Christie’s denouement, but it lingers in the mind long after one has finished the book, and I think it would work very well for a creative-writing class that is examining the nuts and bolts of structure.

Re-read: Till Death Do Us Part (by Carr)

A nice cosy well-plotted village mystery that should appeal to Christie fans who like the Miss Marple books. While I would recommend this one enthusiastically to anyone, I have a slight reservation: a piece of information that we are given early in the book – involving a fascinating, seemingly impossible series of crimes – turns out to be misleading, and this can make a reader feel let down or even a little cheated (that is, if you have set a very high bar for these things when reading Carr: of course the *actual* mystery that he manufactures here is hard to solve too).

Re-read: The ABC Murders (by Agatha Christie)

Most Christie aficionados rate this as one of the very best of the Hercule Poirot novels: though it has never had the larger-than-life reputation of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Murder on the Orient Express, or Death on the Nile, for many of us it is up there with those works. (I would include at least two other Poirot books – Hercule Poirot’s Christmas and Five Little Pigs a.k.a. Murder in Retrospect – in my personal list.)

The ABC Murders is also perhaps the only Christie novel that deals with an apparent serial killer (the term isn’t used in the book, but there are allusions to Jack the Ripper). I first read this one at the age of 12, and I may not have been equipped to fully appreciate it then – in the sense that there is something disorienting about the narrative shifts between Hastings’s regular first-person voice (where he chronicles Poirot’s investigation) and the chapters where he reconstructs things that he didn’t experience firsthand, involving another important character. Glad I reread it after all these decades.

Re-read: Through a Glass Darkly (by Helen McCloy)

I love this poignant, haunting and gently philosophical 1949 thriller, though I wish I had a more elegant-looking edition – this one makes its tragic heroine look like a scream-queen from a B-movie. (Incidentally I have the opposite problem with the John Dickson Carr editions I have bought online – the British Library covers are much too prim and antiseptic, not even hinting at the more pulpy aspects of those mysteries.)

To my mind, this book falls in a special sub-category of the thriller and horror genres – a narrative that centres around an imperilled woman, not so much a helpless “ablaa naari” as someone who is dealing, as best as she can, with a cruel, all-consuming and perhaps inescapable destiny. (When I picture the protagonist Faustina, I always see her as resembling the melancholy Christiane in the brilliant film Eyes Without a Face, trapped in her father’s mansion as he seeks a cure for her disfigured face.)

A no-spoilers plot outline of Through a Glass Darkly: Faustina, a young teacher at a girls’ school, is abruptly dismissed from her position because many terrified people believe that she has a silent, ghostly double – a doppelganger or a Fetch – that can materialise in one place while Faustina herself is in another. As the psychiatrist Dr Basil Willing investigates, he must pit his own rationality against the knowledge that there are things about our own minds which we don’t know; that science has so many secrets to reveal yet. Meanwhile Faustina grows more melancholy as she grapples with the possibility of something un-human within herself.

Wonderfully written book, with a beautiful, ambiguous ending. I wrote a review for Scroll many years ago – here is the link. (Avoid reading the comments section there, since there is a spoiler.)

(More to come, since I have just ordered a few more crime novels of this vintage, including by a couple of authors whom I haven't read before. Meanwhile here are a couple of my earlier crime-fiction pieces for Scroll: impossible crime, rational explanation; and how to make things disappear)

August 14, 2025

In praise of the Father Brown mysteries

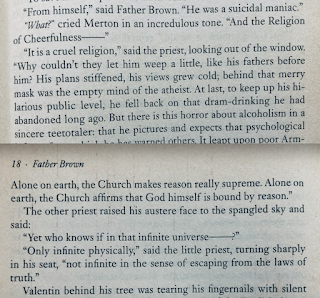

You might think that as a non-believer I’d be somewhat irritated by GK Chesterton’s Father Brown stories – or put off by the little priest-detective’s many snide remarks about atheists. Small and round, droning and monotonous, Father Brown is the most harmless-looking of sleuths: blinking distractedly as he solves a case or makes a big revelation, a gentle soul who believes that the biggest criminals can be redeemed and brought back into the light. But on the subject of non-belief, this sweet man can be mercilessly cutting in his observations – you almost feel he would be glad to see an atheist in hellfire (even if he hadn’t done anything to deserve such a fate).

So there’s a conflict here. And yet, I love the Father Brown short stories – at least the 12 or 13 of them that I have read so far (most of which are from this collection, Father Brown: The Essential Tales, which I borrowed from my friend Samyukta long ago). There is something so rich and evocative about Chesterton’s writing, including the descriptive passages, and there is also something mysterious about the arc of the stories – a narrative often begins on an offbeat, quirky note and it takes a while before you can tell which direction it is going in, and what the nature of the problem (much less the solution) will be. (For a good example, see the first two pages of “The Head of Caesar”, with its description of a particular avenue in Kensington, and a conversation in a little eating-house tucked between tall houses.)

So there’s a conflict here. And yet, I love the Father Brown short stories – at least the 12 or 13 of them that I have read so far (most of which are from this collection, Father Brown: The Essential Tales, which I borrowed from my friend Samyukta long ago). There is something so rich and evocative about Chesterton’s writing, including the descriptive passages, and there is also something mysterious about the arc of the stories – a narrative often begins on an offbeat, quirky note and it takes a while before you can tell which direction it is going in, and what the nature of the problem (much less the solution) will be. (For a good example, see the first two pages of “The Head of Caesar”, with its description of a particular avenue in Kensington, and a conversation in a little eating-house tucked between tall houses.)

The first Father Brown story I read, years ago, was “The Invisible Man”, which was in a big fat anthology of locked-room (or impossible-crime) mysteries – and I was drawn into it by the opening passage, a description of a bright, inviting confectioner’s shop at twilight. But for anyone who is starting on these stories, I recommend that you begin with “The Blue Cross”, which is where we meet the little priest for the first time – through the eyes of the celebrated Parisian investigator Valentin, who, while on the track of a criminal, encounters Father Brown’s remarkable deductive qualities. (The reader’s experience here exactly mirrors Valentin’s: we have his vantage point throughout the story, and Father Brown – initially dismissed as a delicate little naïf – comes into clear relief only in the final few pages; by the end of the story, all our pre-conceptions about what a Great Detective must look and behave like have been swept away.)

“The Blue Cross” also introduces another major character, the criminal mastermind Flambeau who is eventually “saved” by Father Brown and ends up on the right side of the law, assisting the priest in some cases. One of my favourites in that lot is “The Honour of Israel Gow”, an unusual tale about the recent death of an Earl who was living alone in a castle with a half-witted servant named Israel Gow. As Father Brown, Flambeau and others enter this space, they are confronted with several inexplicable objects including piles of snuff, loose diamonds, candles without candlesticks, and lead pencils without cases. Of course, Father Brown does find the connection between these objects in the end – and it’s a marvellous, whimsical solution – but what’s more amusing is that early in the story, he casually comes up with a few other explanations of what the link between these items might be. Before telling his fellow investigators that no, none of these is the right answer. (The effect is a little similar to that of the famous “Locked-Room Lecture” in John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man.)

“The Blue Cross” also introduces another major character, the criminal mastermind Flambeau who is eventually “saved” by Father Brown and ends up on the right side of the law, assisting the priest in some cases. One of my favourites in that lot is “The Honour of Israel Gow”, an unusual tale about the recent death of an Earl who was living alone in a castle with a half-witted servant named Israel Gow. As Father Brown, Flambeau and others enter this space, they are confronted with several inexplicable objects including piles of snuff, loose diamonds, candles without candlesticks, and lead pencils without cases. Of course, Father Brown does find the connection between these objects in the end – and it’s a marvellous, whimsical solution – but what’s more amusing is that early in the story, he casually comes up with a few other explanations of what the link between these items might be. Before telling his fellow investigators that no, none of these is the right answer. (The effect is a little similar to that of the famous “Locked-Room Lecture” in John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man.)

Other stories I have especially enjoyed: “The Hammer of God”, “The Secret Garden”, “The Three Tools of Death”, “The Man in the Passage”, and “The Absence of Mr Glass” (which turns out to be slight, even silly, as a mystery, but is very enjoyable for all that). Looking forward to reading more, though availability is an issue.

August 9, 2025

Some gushing about John Dickson Carr (The Black Spectacles, She Died a Lady, etc)

I have got back to reading John Dickson Carr mysteries from what is generally regarded his peak phase (mid-1930s to mid-40s) – a few of these can now be bought online at not horrendous prices, and delivered within a week or two. (Reading e-books is still not my thing, at least not for cosy Golden Age crime fiction.) Finished and greatly enjoyed his 1939 novel The Black Spectacles over the course of a day. Premise: a nasty episode of poisoning in an English village results in suspicion and hostility directed at a young woman – and is followed a few months later by a strange experiment conducted by this woman’s uncle at his country house, apparently to prove to a small audience that they can’t always trust the evidence of their eyes. (A Hindi translation of this book could be titled Ankhon Dekhi.) Of course, a second murder takes place at this demonstration – practically in front of everyone’s eyes, but with no clarity about exactly what transpired – and soon the formidable, harrumphing Dr Gideon Fell is called in to investigate.

I have got back to reading John Dickson Carr mysteries from what is generally regarded his peak phase (mid-1930s to mid-40s) – a few of these can now be bought online at not horrendous prices, and delivered within a week or two. (Reading e-books is still not my thing, at least not for cosy Golden Age crime fiction.) Finished and greatly enjoyed his 1939 novel The Black Spectacles over the course of a day. Premise: a nasty episode of poisoning in an English village results in suspicion and hostility directed at a young woman – and is followed a few months later by a strange experiment conducted by this woman’s uncle at his country house, apparently to prove to a small audience that they can’t always trust the evidence of their eyes. (A Hindi translation of this book could be titled Ankhon Dekhi.) Of course, a second murder takes place at this demonstration – practically in front of everyone’s eyes, but with no clarity about exactly what transpired – and soon the formidable, harrumphing Dr Gideon Fell is called in to investigate.As most serious crime buffs know, Carr’s reputation and popularity were once almost at Agatha Christie’s level – but he never became a bestselling author worldwide on anything like the scale she did, and many of his books are very hard to obtain today. (One reason may be that some things about Christie’s work – the simplicity of her prose, the tidiness of her plotting – travelled and endured better; so that she was more accessible to readers outside the Anglophone world, including those for whom English wasn’t a first language.)

Something I struggle to articulate about the effect of my favourite Carr novels: I am not usually blown away by the denouement – I mean, I do appreciate the skill and craft, and how carefully plotted the thing was, but it doesn’t necessarily build up to a specific “oh wow!” moment that you sometimes want from a whodunit. At the same time, I can see that this could be because Carr has so much going on simultaneously that his solutions tend to be long and winding, covering much terrain, and you can’t distill the finale to a single gasp-inducing revelation (“They *all* did it!” or “The detective is the murderer!”) More importantly: the fact that the reveal isn’t the most thrilling part of the book – the build-up and the anticipation are more exciting – doesn’t take away from my enjoyment of the whole. Carr is great at creating some genuinely unsettling, creepy moments early on, which work entirely on their own terms as atmosphere-generators for the mystery. (Take the beginning of The Hollow Man, with a masked man gaining entry to a private club and having an enigmatic interaction with one of the patrons.)

Something I struggle to articulate about the effect of my favourite Carr novels: I am not usually blown away by the denouement – I mean, I do appreciate the skill and craft, and how carefully plotted the thing was, but it doesn’t necessarily build up to a specific “oh wow!” moment that you sometimes want from a whodunit. At the same time, I can see that this could be because Carr has so much going on simultaneously that his solutions tend to be long and winding, covering much terrain, and you can’t distill the finale to a single gasp-inducing revelation (“They *all* did it!” or “The detective is the murderer!”) More importantly: the fact that the reveal isn’t the most thrilling part of the book – the build-up and the anticipation are more exciting – doesn’t take away from my enjoyment of the whole. Carr is great at creating some genuinely unsettling, creepy moments early on, which work entirely on their own terms as atmosphere-generators for the mystery. (Take the beginning of The Hollow Man, with a masked man gaining entry to a private club and having an enigmatic interaction with one of the patrons.)That said, The Black Spectacles does have a satisfying and well-worked-out solution; nothing to quibble with on that front. It’s just that I find other parts of the book equally or more compelling – such as the speculation around the possible ways that regular chocolates at a sweet-shop could have been replaced with poisoned ones, or the opening chapter which presents a view of some of the central characters during a trip to Pompeii (as seen through the eyes of a young detective who will later get involved in the case).

P.S. Carr’s most celebrated work is probably The Hollow Man (also published as The Three Coffins), but I tend to agree with Carr aficionados who consider this novel overhyped. (My reasons: engrossing and atmospheric though the book as a whole is – certainly worth a second read – the final explanation is too long and complicated, and I think it can be argued that Carr “cheats” a bit when it comes to the chronology of events in the story; or at least holds back a piece of information that makes it almost impossible for a reader to work things out.)

What The Hollow Man does have going for it – and this is a big reason for its reputation – is an almost standalone chapter titled “The Locked-Room Lecture”, in which the voluble Dr Gideon Fell holds forth on “the general mechanics and development of the situation which is known in detective fiction as the hermetically sealed chamber”. It’s a beautifully audacious ploy to include something like this in a mystery novel (complete with references to famous earlier books such as Gaston Leroux’s The Mystery of the Yellow Room), and it’s done with wit too. (“All those opposing can skip this chapter,” Dr Fell says – and also “We’re in a detective story, and we don’t fool the reader by pretending we’re not. Let’s not invent elaborate excuses to drag in a discussion of detective stories.”)

Incidentally, The Black Spectacles has a fun segment about the mental makeup and methods of the “male poisoner” – drawing on famous real-life cases such as those of EW Pritchard, TG Wainewright and Thomas Neill Cream – that reminded me of the Locked Room Lecture. Not as elaborate, but wry and informative, even as Gideon Fell is being his exasperating self.

Incidentally, The Black Spectacles has a fun segment about the mental makeup and methods of the “male poisoner” – drawing on famous real-life cases such as those of EW Pritchard, TG Wainewright and Thomas Neill Cream – that reminded me of the Locked Room Lecture. Not as elaborate, but wry and informative, even as Gideon Fell is being his exasperating self.P.P.S. perhaps my favourite Carr novel so far is She Died a Lady, a very good mystery on its own terms, with a typically confounding premise (two adulterous lovers appear to have walked to the edge of a cliff and thrown themselves off it – the footprints confirm this beyond a doubt – but when the bodies are recovered, it turns out they were *first* shot and killed at close range!) – but equally fascinating is a narrative ploy that makes the book a very interesting companion piece to one of Agatha Christie’s most famous works. Not saying more.

August 8, 2025

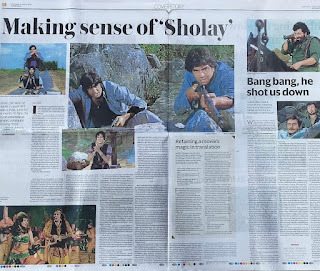

Sholay, in fragments: a 50th anniversary tribute

[Wrote a version of this piece for Mint Lounge, as part of a tribute to Sholay on its 50th anniversary. Have written about the film before, of course – including a 40th anniversary piece which you can read here – and it doesn’t feel like much new can be said. But I took a personal slant here, likening the film to a famous oral epic, imagined and experienced in bits and pieces, never quite “finished”]

---------------------------- Is it possible for the most iconic and mythologised film in your life – the one that is most thoroughly familiar – to also feel like a jigsaw puzzle that took a long time to put together?

Is it possible for the most iconic and mythologised film in your life – the one that is most thoroughly familiar – to also feel like a jigsaw puzzle that took a long time to put together?

Like any other super-fan, I have my personal Sholay history, and it includes this confession: even though the film is central to my pop-cultural journey, looming forever on the horizon like those boulders against the sun in Gabbar’s domain, there have been many gaps in my viewing. Of course I have watched it in the conventional way from beginning to end, at least five or six times (as opposed to the dozens or hundreds claimed by other devotees) – and yet it always feels like I came to it piecemeal through a melange of things heard and read, narratives constructed, back-stories related in magazines and books… and finally, prints with scenes missing in them.

Here’s how this can happen.

****

You’re six or seven, and going for a rare family outing to a hall, to see a film that’s less than a decade old but already fixed in legend. Someone dawdles, you reach 10 minutes after the show has begun, walking into a noisy action sequence involving a train, bad guys on horses, and three leading men whom you recognise. It’s exciting but you’re overwhelmed, and lost about who is doing what: why is one of the “heroes” in police uniform while the other two look roguish, though they all appear to be fighting on the same side?

Then, in the very next scene, Sanjeev Kumar – the cop on the train, energetic and youthful – is older, tired, speaking slowly. You’re not sure what’s going on: the concept of the flashback and flashforward, the idea that these images can jump rudely from one period to another, is not something you have fully assimilated. Anyway, a few moments later the other heroes, Dharmendra and Amitabh (your childhood crushes), looking the same as before, are goofing around on a bike, singing, clowning about in jail.

It’s a night show, you may be drifting off now and again. The spectre of Gabbar Singh arrives: first his name, spoken fearfully many times, and later the man himself. But even amidst the terror of his first appearance, with the minatory music and the belt being dragged along the rocks, you feel confusion: you think he resembles one of the dacoits on horseback – curly-haired, green shirt – from that train scene, and wonder if there’s a link you missed.

A mid-film flashback where Sanjeev Kumar is young again. Through blurry eyes you register the shifts: black moustache to grey moustache, hands to no hands, police uniform to sombre shawl. Later, a fragmented viewing at someone’s house will leave you with more confusion about the two major flashbacks, and more questions about the sequence of events.  Which is to say that there was a time in my childhood when the plot of Sholay was as much of a maze as a convoluted David Lynch or Christopher Nolan film might be.

Which is to say that there was a time in my childhood when the plot of Sholay was as much of a maze as a convoluted David Lynch or Christopher Nolan film might be.

Navigating the labyrinth was complicated by the fact that for a while it was done simultaneously along two mediums: listening to the famous double audio-cassette of the film’s dialogue, and watching a videotape that was much cherished but also problematic.

The audio-cassette was unnerving: you had to identify characters by their voices; it didn’t feature entire songs, playing only the first couple of bars of each familiar tune, before returning to the prose scenes. Some excitement lay in the details – I was tickled to bits by the line “Thakur ne hijron ki fauj banayi hai”, not having expected to hear a word like that in a film – but on balance I preferred to watch Sholay, not hear it.

The videotape, one of my favourite childhood possessions, came for some reason from faraway Lagos, brought by a visiting uncle who had been assured that the thing I wanted most in the world was my own Sholay cassette. I was ten now, we had just got a video player at home, and I must have worn it out over days with this tape. The train flashback now made sense to me, as did the overall chronology (though there was still some disorientation in, for instance, seeing Gabbar’s henchman Kaalia alive and gloating in a flashback after he had been bumped off in that sadistic roulette scene).

At last I was getting to watch the complete film, from start to finish. Or so I thought.

There were abrupt cuts here and there, especially in the first hour – it took some time to realise that chunks had been snipped to fit the VHS’s 180 minutes. Which meant that years after my first, mysterious hall viewing as a small child, some things still had to be figured out.

Sleuthing, carefully matching the video footage with the audio on my dialogue-cassette, I realised that the scenes involving Soorma Bhopali (Jagdeep) and the Hitler-like jailer (Asrani) had been excised in the former. That makes some sense if you have to cut 15 minutes: those sequences are fun and show off the skills of two fine character actors, but they are dispensable to the main narrative, and they greatly delay Veeru and Jai’s arrival in Ramgarh.

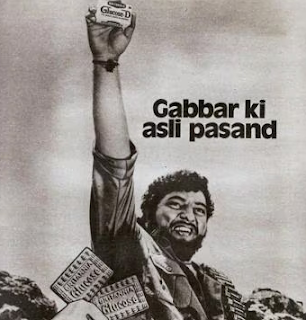

Even so, I feel cheated that it took me years, maybe decades, to realise that the beloved Keshto Mukherjee had a small role in Sholay (in the jailer scene). Things were also complicated by the fact that Sholay’s characters were continuing with their lives in other forms and media. Gabbar Singh was selling glucose biscuits in ads long after he had been vanquished (or killed, in the ending that was shot but not released). In the late 1980s came a film called Soorma Bhopali with Jagdeep, featuring Dharmendra and Bachchan in cameos unrelated to their Sholay roles; after that, Ramgarh ke Sholay, which seemed cheap and B-grade-ish, being filled with star-impersonators, but which still had the real Amjad Khan (looking much paunchier, as if Gabbar had taken his role as biscuit mascot too seriously).

Things were also complicated by the fact that Sholay’s characters were continuing with their lives in other forms and media. Gabbar Singh was selling glucose biscuits in ads long after he had been vanquished (or killed, in the ending that was shot but not released). In the late 1980s came a film called Soorma Bhopali with Jagdeep, featuring Dharmendra and Bachchan in cameos unrelated to their Sholay roles; after that, Ramgarh ke Sholay, which seemed cheap and B-grade-ish, being filled with star-impersonators, but which still had the real Amjad Khan (looking much paunchier, as if Gabbar had taken his role as biscuit mascot too seriously).

*****

Between all this, during my video viewings, Sholay did perform the epiphanic functions that a landmark film is expected to. For instance, I can never forget the tense scene where the villagers turn hostile towards their mercenary protectors, because this was the moment when the idea first entered my nascently movie-obsessed head that a camera movement is a deliberate, engineered thing that builds meaning: when the line “Kab tak jeeyoge tum, aur kab tak jeeyenge hum, agar yeh dono iss gaon mein rahe?” (“How long will we stay alive if these two remain in the village?”) is accompanied by a camera swish that places Veeru and Jai at the centre of the frame, precisely on the words “yeh dono”.

I learnt about the mysteries of personality too, and how a creative work can bring catharsis or draw out aspects of yourself that you hadn’t fully processed yet. As a painfully shy and quiet child with a taste for sardonic humour, there was every reason for me to relate to Bachchan’s Jai; instead I was always more drawn to, and even felt a kinship with, the boisterous Veeru.

But that Nigerian tape was also responsible for the biggest of my Sholay gaps – one I was unaware of until well in my thirties. That’s how old I was when I watched Sholay’s great opening-credits sequence for the very first time. While that might not be a big deal for most Hindi films of the period, in Sholay the craft and attention to detail begins right here – in the scene where the manservant Ramlal leads a policeman on horseback from the railway station to the Thakur’s haveli.

My tape had the credits only until the names of the six principal actors; there was a sudden cut after the title "And Introducing Amjad Khan". This is a major bone I have to pick with the anonymous tape-editor sitting, in my mind’s eye, in some squalid little Lagos bootleggers’ shop. Because, watching the full sequence on DVD decades later, I saw how it sets the stage, giving us a detailed view of Ramgarh and its surroundings, long before the narrative actually takes us there. The superb RD Burman background score changes from a guitar-dominated tune as the riders move through a barren, American Western-like setting to a more Indian sound, with mridangam and taar shehnai, as they pass through the village. The symbolic nature of Sholay’s mise-en-scene is made obvious here too, with the contrast between swathes of rough landscape (where the dacoits, creatures of the wild, perch like vultures) and the village, where people live together in an ordered community – a setting that will soon welcome two rootless men who will learn about taking on responsibility and integrating into a larger world.

So here was a clear case of me watching a segment of Sholay as an adult with no pre-conceptions, seeing something new and being utterly impressed. When I screened and discussed the sequence in classes, the discussions were perceptive, intense and wide-ranging – even when they involved students who had never actually watched the film. (Yes, there are now many such movie buffs.)

It is widely acknowledged that Sholay was the most polished and fully realised of the Hindi films of its era, the most flawless technically, the one with the best action scenes and sound design, the fewest loose ends or awkward cutting. The sort of mainstream film that even Satyajit Ray could (grudgingly?) admire. But however complete it may be, I think of it as a series of unforgettable moments that are so deeply embedded in one’s consciousness (and so easily accessed from the mind’s old filing cabinet) that it almost doesn’t matter which order those fragments come in – there are any number of entry points. It’s a bit like knowing key sections of a legendary epic – say, the Mahabharata – and still feeling like you know it in its entirety. But the possibility of being surprised by a detail here, or a fresh re-watch, still exists, even for old fans who thought there was nothing more to learn.

July 22, 2025

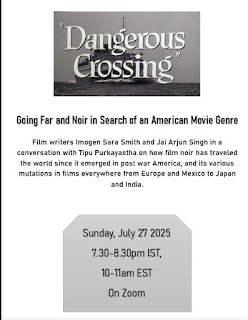

An online chat with Imogen Sara Smith

So noir yet so far: my friend Tipu Purkayastha and I will be in conversation with the writer and film scholar Imogen Sara Smith on July 27 – it’s open to all, so please try to join. Imogen has written on many things (including a book on Buster Keaton and some fine essays on the Criterion Collection website), but the topic for this discussion is film noir as it has travelled outside America – moving from its gritty urban contemporary roots to different locales, languages and sensibilities. Including, of course, the Indian version of noir as manifested in old Hindi cinema (e.g. the Navketan films of the 1950s) as well as the neo-noir of more recent decades.

So noir yet so far: my friend Tipu Purkayastha and I will be in conversation with the writer and film scholar Imogen Sara Smith on July 27 – it’s open to all, so please try to join. Imogen has written on many things (including a book on Buster Keaton and some fine essays on the Criterion Collection website), but the topic for this discussion is film noir as it has travelled outside America – moving from its gritty urban contemporary roots to different locales, languages and sensibilities. Including, of course, the Indian version of noir as manifested in old Hindi cinema (e.g. the Navketan films of the 1950s) as well as the neo-noir of more recent decades. Please DM me (or email at jaiarjun@gmail.com) for the Zoom link.

July 21, 2025

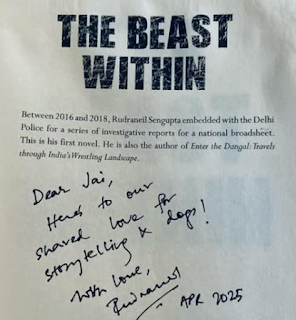

A short recommendation: The Beast Within

Putting up a few short posts about books I haveenjoyed in the past year, which I have mentioned elsewhere but not here.One of them is RudraneilSengupta’s crime novel The Beast Within, about a police investigation centredaround a suspicious death in Delhi’s Panchshila Park. (This, incidentally, hitsa little too close to home, given that I have a new flat in that colony *and*there has been a spate of crime in Panchshila in recent times, including amurder.)

Putting up a few short posts about books I haveenjoyed in the past year, which I have mentioned elsewhere but not here.One of them is RudraneilSengupta’s crime novel The Beast Within, about a police investigation centredaround a suspicious death in Delhi’s Panchshila Park. (This, incidentally, hitsa little too close to home, given that I have a new flat in that colony *and*there has been a spate of crime in Panchshila in recent times, including amurder.) The Beast Within isn’t a mystery so much as aprocedural that goes in many different directions, with a team of cops having todeal with – among other things – pressure and bullying from the well-heeled andthe well-connected. I particularly liked the pacing and the continuous shift ofperspectives between the policemen (and one policewoman, the book’s mostendearing character, a former wrestler named Meera Kumari), with their approachto the investigation being rooted in their backgrounds, biases andpersonalities.

I couldn’t attend all of Rudraneil’s recent bookdiscussion (featuring author Madhulika Liddle and Monika Bhardwaj, the first womanDCP in the Delhi Crime Branch – a pic from that here) but I did get to brieflymeet him there. We had first been in touch during Covid times because of ourshared activities in street-animal care, and the book has a couple of passageswhere Meera – an animal-friend herself – explodes at people who are rantingabout the “stray dog menace”. Very relatable. Lara (seen above), Chameli and others would like this fictional woman cop, I think.

I couldn’t attend all of Rudraneil’s recent bookdiscussion (featuring author Madhulika Liddle and Monika Bhardwaj, the first womanDCP in the Delhi Crime Branch – a pic from that here) but I did get to brieflymeet him there. We had first been in touch during Covid times because of ourshared activities in street-animal care, and the book has a couple of passageswhere Meera – an animal-friend herself – explodes at people who are rantingabout the “stray dog menace”. Very relatable. Lara (seen above), Chameli and others would like this fictional woman cop, I think.

<font size="4"><span style="font-family: trebuchet;">@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073732485 9 0 511 0;}@font-face {font-family:AppleSystemUIFont; panose-1:2 11 6 4 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-alt:Calibri; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:auto; mso-font-signature:3 0 0 0 1 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0cm; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</span></font>

July 20, 2025

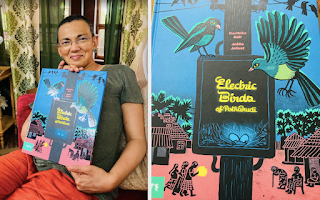

Trivandrum diary: meeting Karthika (and a few dogs)

From earlier this month… my dear friend (and fabulous writer and poet and fellow mythology buff and cinephile and all-round inspiration) Karthika Nair couldn’t make it to Delhi during her recent India trip, so I hopped down to Trivandrum to see her on her home turf - in the quiet and picturesque Vellayani Lake area. It was great to spend an afternoon talking about this and that, and to meet her family. (Including the dogs who, after some initial yelling, recognised me as the alpha dog I am and paid respectful tribute.)

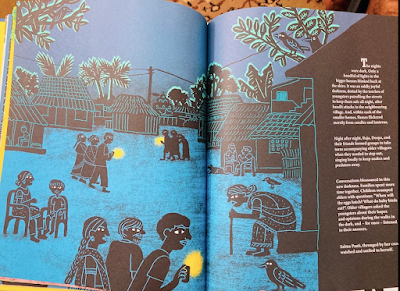

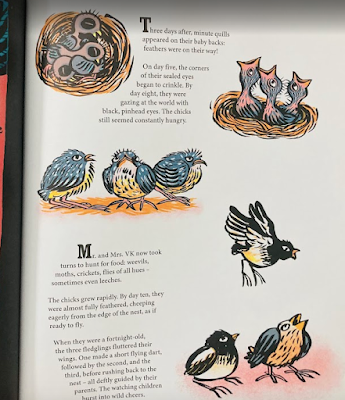

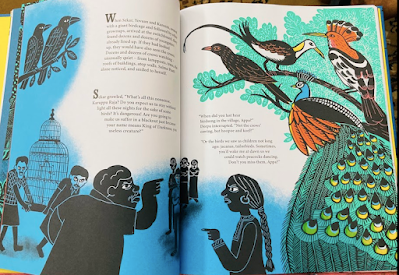

I also looked through the beautiful book Electric Birds of Kothapudi, a modern fable written by Karthika (I had read an early draft of it a couple of years ago) and brilliantly illustrated by Joelle Jolivet. The book isn’t published in India yet, but it really should be - fingers crossed.

I also looked through the beautiful book Electric Birds of Kothapudi, a modern fable written by Karthika (I had read an early draft of it a couple of years ago) and brilliantly illustrated by Joelle Jolivet. The book isn’t published in India yet, but it really should be - fingers crossed.

A couple of pics from the book are below, and here is a post about another superb collaboration between Karthika and Joelle, The Honey Hunter. And a conversation with Karthika and Sampurna Chattarji about their book Over and Under Ground in Paris & Mumbai, which also had drawings by Jolivet and Roshni Vyam.

(Last few photos: at the end of a long, long early-morning walk around Kovalam, I found myself at the lighthouse beach, where this black-and-white fellow contemplated me a little fearfully. Glad to see that "progressive" Kerala hasn’t slaughtered all of its community dogs yet - I also found a few lazing on the beach outside the Uday Samudra resort. Sand, shadow and sleeper in the last pic.)

(A long conversation with Karthika about her superb Mahabharata book Until the Lions is here)

July 18, 2025

Wicked game to play: an unexpected cameo in Silence of the Lambs

I re-watched Silence of the Lambs a few weeks ago and had a few thoughts about it – including a memory-trigger of my strangely bifurcated first viewing of the film in 1991: my mother and I watched a little more than half of it together at night on cassette, and then finished it early the next morning before I left for school! A very strange thing to do with this film. We may have been awkwardly silent during the full-frontal-nudity scene where Buffalo Bill, having tucked his penis behind his legs to make himself look female, sways about in front of the camera.

I find I’m not too impressed any more by Anthony Hopkins’s performance as Hannibal Lecter. (I know it isn’t fair to compare the three on-screen Lecters, given that they serve such different functions in their respective films/shows – but I think Brian Cox in Manhunter has a matter-of-fact menace that Hopkins doesn’t. Mads Mikkelsen in the TV series of course gets to develop many shades of the character over dozens of episodes, so maybe *that* isn’t a meaningful comparison at all.) Jodie Foster is excellent though, and makes it easy to see that Clarice is the clear protagonist of the film (and the book), in much the same way that Will Graham is the protagonist of Red Dragon and its film versions.

Anyway, here’s a more unexpected observation: in the scene where Lecter escapes, there is an actor playing a SWAT team leader who I thought was the spitting image of Chris Isaak. Then I looked it up and discovered that it *was* Chris Isaak. Surprising. It’s a very brief part but he is convincing enough in it.

Anyway, here’s a more unexpected observation: in the scene where Lecter escapes, there is an actor playing a SWAT team leader who I thought was the spitting image of Chris Isaak. Then I looked it up and discovered that it *was* Chris Isaak. Surprising. It’s a very brief part but he is convincing enough in it.

Unfortunately, now whenever I think of Silence of the Lambs, the song “Wicked Game” will play in my head…

Jai Arjun Singh's Blog

- Jai Arjun Singh's profile

- 11 followers