Rob Ryser's Blog: excerpts from The Wall at newquoin.com

March 3, 2014

The First Book of Meaning for the Non-Reading

Announcing

Marble Arch: Reading for Revival, Revolution and Renaissance

The only book that feeds what non-readers need.

You can help reach non-readers on their own terms for the first time

and make meaning appealing to those who no longer read.

This is renewal that can only be fueled by heroes like you.

Be a Champion of Meaning

June 19, 2013

Verses of Change

We’ve lost our art.

Oh, we may argue about it.

But we look at the world around us. We look at the world inside us.

We know art’s gone.

And we’re not sad.

Part of what it means to be American is to devalue what’s lost.

Because what’s art anyway if it’s not with us?

Maybe it would matter more to us if we weren’t so well entertained. Maybe if we didn’t have such seriously good entertainment, we might miss art more.

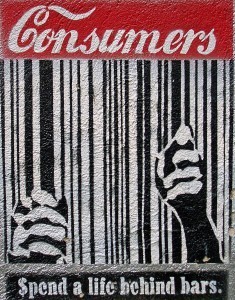

But the truth is we have all the entertainment we want. American entertainment pursues us. American entertainment puts us at ease. American entertainment provides everything we need.

And so we’re content.

We’re more than content to live without art.

And why should we change, now that we’re mature enough to accept things the way they are?

The answer is that none of us can accept things the way they are.

We look at the world around us. We look at the world inside us. And there’s too much pain.

We’re slaves to what we can’t overcome. We’re estranged from our own heart. We want another chance but it won’t seem to start.

To change the pain we need to look beyond what entertains for the art we lost.

II. Keeping Change Out of Range

We could challenge the argument that we’ve lost our art.

But we know ourselves better now than at any other age.

And we know that the classical music stations on the radio and the quarterly poetry readings at the library and the new art galleries uptown are no more evidence that we’re art lovers than the existence of peace groups is evidence that we’re pacifists or the existence of human rights groups is evidence that we’re just, or the existence of churches is evidence that we love our neighbors as ourselves.

We know that we’re no more a well-educated nation because of the existence of schools than we’re a well-read nation because of the existence of books.

The facts back us up: when we look at our population as one body, we Americans do not read literature anymore.

The last time the National Endowment for the Arts counted, 38 percent of men read literature. The figure for women was 55 percent. Taken together, that means less than half of Americans now read literature.

It’s a dramatic and depressing decline of our print culture that means we’re less and less informed about civics, less and less engaged in service and less and less alive as a society. Former NEA Chairman Dana Gioia calls it an “imminent cultural crisis.”

But what do we care about culture? What we care about is ourselves.

And we don’t care to change.

We don’t care to change because we believe we don’t need to change. We don’t care to change because we’re afraid we can’t change. We don’t care to change because we think it will make us worse off.

So speaking change to us who don’t want to know only hardens our soul.

Fine.

But we can’t complain about pain anymore, because change transforms pain, and we don’t want change.

And we can’t hurt others because we hurt anymore, because we could change if we choose, but we don’t choose to.

And we can’t bring down life around us anymore, because change could save us, but we don’t want to be saved.

We can only remain the same in an artless age.

We continue to starve for beauty. We continue to be beaten by lies. We continue this way thinking art can’t open our eyes.

III. The Cost of What’s Lost

We’re not stupid. We know what we’ve lost. We remember how it felt in our youth to get high on discovery. But now we have too much to lose, and change is for fools.

So let’s not fool ourselves: we no longer explore the core where learning and meaning are inspired by art. We’ve drifted to the rim where we displace our restlessness with entertainment. By settling for the superficial and staying away from substance we are as far removed from art as change is from our heart.

That goes for those of us who’ve used the phrase ‘embrace the chaos’ to suggest that we’re moving towards the center instead of perishing on the perimeter. ‘Embrace the chaos’ is one of those pop proverbs that tricks the ear where the truth is supposed to ring. It sounds like counter-intuitive wisdom while it actually reinforces error.

‘Embrace the chaos’ suggests that change is more about quick reaction than it is about lasting reform. It burdens our concept of change with anxiousness about the outcome and fear about our fate.

Chaos is what change looks like when we don’t know who we are or where we are going.

When we’re not grounded with a sense of origin and a sense of destiny, the world seems to run on dumb luck. Purpose seems like an elitist conceit. Utilitarianism rules.

It shouldn’t surprise us that the change we need to recover from self-destructiveness and to reconcile estrangements and to regenerate love is not encouraged by our culture, because our culture doesn’t want us to think for ourselves any more than we want to think for ourselves.

Our culture works overtime to learn each of our archetypes. Our culture doesn’t like unpredictable patterns of non-commercial activity.

Nowhere is this truer than in entertainment, which is at its best when it’s spoon-feeding us.

Many of us have developed a high tolerance for being spoon-fed, because we associate it with maternal pampering that caters to our primal desires. Rarely do we bristle at the manipulation behind entertainment that exploits our need to escape our burdens.

Entertainment only gets away with doing for us what we can do for ourselves with our consent.

So it startles us that there is no spoon-feeding in art. It unsettles us that we don’t know what to think about art, because art doesn’t follow the entertainment formula. Many of us have developed a low tolerance for art that forces us to think, because we associate it with paternal abandonment. We find it cold to be told to work out what we see and to figure out what we believe.

This widens the divide between art and entertainment.

Unlike entertainment that tracks our movements and pops up on us everywhere we check in, art is something we must pursue. Unlike entertainment that pacifies us, we wrestle with art. Unlike entertainment that does everything for us, art will never do for us what we can do for ourselves.

And so we let art go.

We let art go even though it leaves a hole that nothing else can close. We let art go even though we know it carries our hope.

IV. The Art of Inner Life

Our hope is that we can fully believe in who we are. Our hope is that we can fully buy into our purpose. Our hope is that life will reveal its full meaning in order that we might withstand what we have to suffer and we might accept what we have to sacrifice in order to live happily ever after.

This is the source and the summit of our interior life. This is our inmost reality that has no exterior expression in secular life except in art.

And if art is lost to us, it’s because we’re lost to ourselves.

Art can’t change that.

Art gives us a stage to play out our interior life. Art allows us to identify our deepest experience in others. Art allows us to transform our suffering into solidarity and to convert our solitude into communion. But if we don’t bring knowledge of ourselves to art, all we have a dark stage with no actors. Important ideas about our existence must be in orbit for us to explore our core through art.

Art awakens mission by stimulating in us a sense of who we really are outside of profession and education and romantic love. It stirs in us a conviction about our claim on the world and the world’s claim on us. But if we don’t bring an inner awareness of ourselves to art we won’t recognize the call to mission.

Art will meet us in our efforts at recovery. Art will confirm us in our efforts to reconcile. Art will feed us in our efforts to start anew. But we must first do for ourselves what only we can do.

If we have stopped learning because we are through with education, if we have stopped serving because we are through with giving, then we have lost faith, because we are through with living.

And art won’t come to our rescue.

We’re past the age where youth can save us.

We change or we die being the same.

V. The Treasure of Slow Art

Everyone has a relationship to art because everyone has an interior life that needs to be engaged.

It’s up to us to overcome ourselves. It’s up to us to acquiesce to others. It’s up to us to begin a new.

But if we are to spark revival and start a revolution and reach our renaissance, we must have art, too.

It’s art’s job to reveal to us who we really are.

It does not matter for now that we Americans are not producing enduring art. There is enough fat in the masterpieces and the classics of the past to last our lifetime.

But it does matter how we come to art once we have made our new start.

We must remember to weigh art slowly. And we must remember to weigh art for treasure, not for pleasure.

When it comes to literature we need to teach ourselves how to read.

First, we need to teach ourselves to read slowly.

When we read slowly we inevitably will pick up lines that we would have no time to consider while reading at a speeding pace. Slow reading encourages lingering and the search for meaning. Speed-reading encourages line skipping in search of entertainment.

When we read fast for plot we pass over sentences that don’t contain action key words because we suspect those sentences have nothing to do with the advancement of the entertainment.

But the true movement of art is on the inside.

For example, in the middle of a complicated love square in the Cervantes novel “Don Quixote,” two beautiful women and two handsome men are confronting each other in a climactic scene. One of the women lays out all the ways she has been wronged by the circumstances of being forced to love the wrong man. And the man makes the following statement:

“You have conquered, for it is impossible for the heart to deny the united force of so many truths.”

The reader must stop and consider this for a moment. It is true that it is impossible for the human heart to deny the united force of many truths?

If it is, observe how applicable such insight is in our relationships, and in the management of our pride.

Consider all the times in life we are working against ourselves. Consider all the moments we are working against others. Would not this knowledge of our own heart help us concede battles and surpass obstacles by giving us a superior understanding of our own workings?

This is what art does for us when we come to it slowly. Art exploits the hidden life.

This is just one example from Cervantes’ masterpiece that some consider the greatest novel ever written. And while “Don Quixote” is certainly entertaining, Cervantes did not create the scene between four lovers to gratify our lustful leaning, but to enlighten our life of meaning.

This leads to the second point: We need to teach ourselves to read for treasure, not for pleasure.

Pleasure is perishable. Treasure endures. Treasure is what we want more than anything else. Even if we say what we want more than anything else is pleasure, we don’t mean it, because once we have pleasure we are not satisfied until we can have more.

We even become bored with pleasure.

But we are never bored with our hearts. And where our treasure is, so our hearts are.

If we read for treasure we will have art in our heart and we can find the happiness that eludes our pursuit.

May 13, 2013

The Dust of Justice

If we could wish for just one thing that would fix our world, and if we could make that wish with the full confidence that the wish would be granted, we would all wish for justice.

Yes, we might first think to wish for peace, but we would stop ourselves right away, because we know better.

We know that there can be no heaven on earth in a free will world, so we don’t waste our faith wishing on utopian things like peace.

Justice on the other hand seems achievable to us, even if the idea of universal justice is just as utopian as world peace.

Justice is the one burning ideal we have as a civilization. We know what justice looks like. It never seems to be widespread or lasting, but we have seen justice accomplished on small scales.

We know there is a greater justice in us.

It is important to get that clear.

We are not talking about the small scales of justice here.

We are not talking about the need for law and order. We are not talking about the history of crime and punishment. We are not talking about suffrage or freedom marches or the righteous fight for equal rights.

We are talking about justice that is deeper than civics.

We are talking about the moral core of justice that resides in the dark of every human heart.

We are talking about the justice of perfect judgment that rights all wrong.

And by us wishing for that kind of perfect justice above all else, we say more about what is wrong with us as Americans than by anything else.

By wishing for perfect justice we mistake what we really need as people and we mistake what we really need as a world.

Worse, we are mistaken in the most ironic way. Not only we are oblivious to the error of our own desire, but the justice that we request for our repair actually adds to our despair.

The truth is we don’t really want perfect justice.

What we want is mercy.

But we don’t wish for world mercy, because we don’t want mercy for the world.

We only want mercy for ourselves; for everyone else we want justice.

And so our wish for perfect justice is unjust.

II. The Chill of Free Will

It is good to wish for a just world. But it is better to wish for a just soul.

The first wish is not attainable because the second wish is not desirable, so we take refuge in fantasy.

But we are quickly brought back to earth by our own brokenness.

No wish can be granted where free will reigns.

Take for example our wish to live happily ever after: we know that this wish is a fantasy that could only come true on earth if our free will breaks.

The testimony of our life is proof that when we exercise our free will, we do not make choices that lead to happiness ever after.

We make choices based on greed and desperation and insecurity. We make choices to deliver gratification instantly. We make choices for ourselves instead of for the common good.

We do this over and over and over, and we say we are only human. But our conscience doesn’t accept our own excuse, because our conscience knows that we are capable of overcoming our nature.

And every time we don’t overcome our nature, we understand the consequence.

The consequence is we will never have our wish to live happily ever after.

In the same way, as long as we have our free will, we will never have our wish for world peace.

Deep down we do not wish for peace. The testimony of our interior life is proof of this.

We want death for our enemies. We want defeat for our adversaries. We want less than the best for those we detest.

We want abundance for ourselves. Everyone else can suffer want.

What good is it to enjoy the good life if everyone else is enjoying the good life too?

We don’t like this part of ourselves. We repress it to our subconscious. And we try to will ourselves away from it.

But there it is all the same.

The problem with injustice in the world is not that the world is unjust. The problem with injustice in the world is that we are not just.

This is something we can change.

III. The Justice of Suffering

The main thing we Americans must change if we are to have a just soul is our hardness to suffering.

We must overcome the idea that suffering is a disgrace that cannot be embraced.

Intellectually, we know that resistance to suffering causes more torment for us than the actual onset of affliction. And yet we resist suffering anyway because suffering is so offensive.

The offense of suffering is not so much the pain of it but the injustice of it.

Whether it is sudden loss or sudden crisis or sudden affliction, suffering seems invariably aggressive, invariably intrusive, and invariably punitive.

We think that only suckers suffer.

But of course our greatest heroes have all suffered. In fact, what makes them greater than us is that they suffered better than us.

We can’t think of a great person who didn’t suffer seriously and who didn’t suffer admirably.

Great people overcome the objection to suffering that they don’t deserve it.

But we think we don’t deserve to suffer even when we have done wrong.

And we can’t get over the fact that the innocent suffer – especially children who are abused or abandoned.

And we shout, “Where is the justice in that!”

But the burden of suffering is not eradicating the injustice of it.

The burden of suffering is identifying the humanity in it.

The message to the soul struggling with suffering is not that life is worth living, but that suffering is worth enduring.

The meaning of suffering is mercy.

Instead of seeing suffering as a sign of division and a call to war, for which we go on to justify all sorts of brutality, we must see suffering as a sign of humanity and a call to solidarity, for which we go on to justify all sorts of sacrifice.

This is not to glorify suffering.

This is to reveal suffering.

To endure suffering with acceptance shows two things: it shows that we have faith, and it shows that we have grace.

Faith is the way we love God. Grace is the way God loves us.

And we already know that love conquers all things, because loves endures all things, even injustice.

April 6, 2013

The Danger in Nature

CROSS RIVER – It’s difficult to think of something that is more in harmony with American values than nature.

It’s difficult to think of an idea that is more rooted in our sense of individualism and more suited to our need for community than being natural.

When people are grounded and virtuous we say they have good nature. When something is balanced and self-sustaining, we call it a natural process. When something is beautiful beyond imagination we call it a natural wonder.

Nature is both the default we try to revert to and the upgrade we try to convert to.

In fact, our popular conscience in America is so informed by the high ideals of nature that we rarely think of the crude and cruel qualities of the wild world around us.

If we speak ill of nature at all it is to blame our failings on inherent weakness, which we call human nature, even if we do it more to exonerate our nature than to fault it.

After all, we’re only human.

But it’s dangerous to put too much stock in the nature within us, and not put enough faith in the higher state that awaits us.

The danger is that we are not nature.

Nature needs no revival. Nature needs no revolution. Nature needs no renaissance.

We do.

Unlike the beauty and the order of the natural world that needs no reform to thrive, if we fail to transcend our human nature we don’t survive.

II. Beyond Instinct

It’s not just our time that is obsessed with the idea of nature, of course.

In every generation, nature has been the inspiration of exploration, the muse of art, and the manifestation of divinity.

In one of the great spiritual classics of all time, St. Francis de Sales in his “Introduction to the Devout Life,” makes frequent use of the natural world to open new views into virtue.

“Taken alone, hemlock is not a quick but rather a slow poison and can easily be cured, but when taken with wine there is no antidote for it. So also slander that might by itself pass lightly in one ear and out the other, as we say, sticks in the hearers’ mind when expressed in some subtle, funny story.”

And in one of the great American literary classics, Thoreau retreats to the woods to live for two years near Walden Pond outside Concord, Mass., creating a masterwork of ecology, philosophy and theology.

“I was suddenly sensible of such sweet and beneficent society in nature…an infinite and unaccountable friendliness all at once like an atmosphere sustaining me.” Thoreau goes on to call nature “too pure to have market value, more beautiful than our lives, more transparent than our characters.” Thoreau sees in the morning of a spring day “no stronger proof of immortality.”

Just as it was generations before us, nature is our medicine cabinet. Nature is our grocery store. Nature is our playground. Nature is our laboratory. Nature is our art gallery. Nature is our church.

Nature is our life.

And yet we are greater than our nature.

St. Francis knew that. Thoreau knew that.

We need to remember that too.

The trees and the sea and the stones and the bees are fixed agents, because nothing in nature has free will.

Therefore, the lilies need no clothes, the sparrows need no wages, and the seasons need no treaties.

Nor does nature need solidarity. Or virtue. Or forgiveness.

But we do.

Nature may be ours by default, but character is only ours by choice.

And if we do not use our free will to overcome our nature, we succumb to it.

III. The Fall of Us All

The happy platitude that we get a little better each day is a wonderful encouragement in a world of uphill struggle that we probably draw from a faulty reading of nature that life in the wild is always evolving to a better state.

It isn’t true.

Charles Darwin, the author of “The Origin of the Species” and the architect of the theory that variation is preserved through natural selection, wrote to a colleague in 1856 “What a book a devil’s chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering, low and horribly cruel works of nature!”

But even if we accept the popular picture of the ever-improving process in nature, and even if we acknowledge the truth in adages such as ‘what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,’ we all know that it is impossible to maintain anything like an ever-advancing record of perpetual forward progress.

In fact, there is evidence in each of our lives to make the case that we get a little shittier each day, and that the only thing keeping us from a more rapid pace of devolution is our virtuous efforts to resist it.

This reverse inertia is obvious in our physical lives once our grown bodies start to age. We can also observe this difficulty making progress in our mental health, even with the benefit of experience. Even with the aid of treatment.

But nowhere do we see this entropy clearer than when it comes to our moral lives. The way we treat other people simply does not get a little better day by day. We may make wonderful gains only to be set back by anger, pride and envy.

We may succeed in treating others the way we want to be treated until we are hurt or until we are abused or until we are betrayed, so that we can’t help but withdraw or lash out.

Or we may decide to avoid future conflict by protecting our exposure and by setting ourselves on a determined path to do no harm, only to find ourselves doing no good either.

Then there are all those times that we get in our own way, either because of character defects or because of character defenses.

It all comes to this: the moral life that we expect of ourselves may be possible to live today, but it is impossible to live every day.

And yet we must try to do it anyway if we are going to be happy.

So we look to nature’s blind and primal ways for inspiration and imitation.

But we see no morality in nature.

There is no right or wrong in rain.

There is nothing to show us the way to overcome ourselves in the wild.

So we must take un-natural chances and make artificial advances.

IV. Evolution, Devolution, Revolution

It’s all the rage to say “that’s just not natural.”

If something scandalizes us Americans, we call it unnatural. Never mind that this ‘unnatural’ act could be offending us because it challenges our own values, or it could be offending us because it upstages our own virtue.

What we are really doing is building up our nature by tearing down our spirit.

To us, being natural means having common sense. To us, common sense is the most genuine kind of sense and the most authentic kind of sense and the most organic kind of sense.

We Americans praise common sense so highly because we are so used to celebrating the wonderful things of life that come to us through sight and touch and taste and sound.

But the truth is that common sense is common. Common sense is what comes to us through the senses. Common sense excludes everything beyond the limits of sensory perception.

Common sense is as low as nature can go.

So when we condemn something that confounds by calling it unnatural, we are saying that it cannot be reconciled with the crude and primal instruments of understanding.

Calling something unnatural is the most ironic kind of condemnation, because with the same tongue that we are protesting error, we are confessing truth we don’t perceive.

Man is not evolution. A man who trusts in evolution devolves. Man is revolution. Man is constantly in need of reform because man is constantly exercising his free will imperfectly.

The mistake is not seeing ourselves in nature. The mistake is believing ourselves to be nature.

We can get to the higher state of the spirit where our souls know we must go if we are willing to let go of our nature.

February 28, 2013

The Revelation of Education

NEW YORK – Growing up in Chicago, nobody taught me to be an education hater.

Yes, my teachers presumed that grammar and math and history were my good fortune to learn. And I hated all that instruction about nothing.

But it wasn’t my teachers who taught me to loathe learning, because I despised extra-curricular education more.

Yes, my father presumed that baseball was my destiny and he coached into me hitting philosophies and fielding fundamentals and training disciplines. And I hated all that exercise about nothing.

But it wasn’t my dad the coach who fueled my reproach for learning, because I despised social education still more.

Yes, my peers presumed that my idea of success was acceptance, and that my idea of happiness was popularity. And I hated all that posturing about nothing.

But it wasn’t my friends who chilled my yearning for learning, because what I despised most of all was self-education.

I despised self-education for the same reason that I despised all education: I was always offended by people telling me what to do.

It all started from my earliest acquaintance with my conscience; I never wanted to listen to my own voice.

As a result, I grew up learning nothing and believing nothing and seeing nothing wrong with knowing nothing.

No doubt my experience is difficult to relate to for many people. But I’ve found that the place I wound up as a consequence is not so different from the place other baby busters wound up, with their midlife ahead of them and their education behind them.

There I was, a man near 30. I was a husband and a father, a nine-to-fiver and an every-night partier. I had no knowledge about life-changing thought. I had every intention to lead the unexamined life by living through the body.

When the anxiety hit, I swiped back with gin. When love wouldn’t trade, I let it fade. When I became incoherent to myself I pursued oblivion. But I could only go on so long being my own unhappiness.

What came next should never have happened to a man like me. But it did. And it was all for the purpose of my education.

II. When Free Will Seizes

It doesn’t matter that my issue with education in Chicago was one of my will and not one of my ability, because I wouldn’t have been able to distinguish the difference back then anyway.

Had someone told me back then, as I tell students now, that the primary goal of education is to learn how you learn, it wouldn’t have mattered to me, although I probably would have paid a bit more attention, being a narcissist, had someone pointed out that I was the real subject of the lesson and not the grammar or the math or the history.

The goal of education is to give us skills to cure injustice, to appease conflict and to endure suffering so that we can sustain life-long bonds and protect people entrusted to us and serve people in need. To develop these skills we must learn how to be critical thinkers and careful observers and radical humanitarians.

Try teaching that to me back then.

My problem in school and my problem on the ball field and my problem at the park after dark with my binge friends had a single source: I didn’t know myself.

As a result, I had the wrong idea about what learning was, and I had the wrong idea about what learning does.

My first mistake was thinking that education was something external that I had to reach for and secure with great labor, instead of thinking of education as something internal that I merely had to switch on to activate.

I compounded that mistake by thinking that there was only one way to learn – the way the particular teacher taught, or the way particular classmates thought.

For example, I had the wrong idea that reading was something that was supposed to come easily and quickly to everyone, and that if I did not absorb a story fully on the first take, it was because I was not smart enough to understand it.

I didn’t know that the goal of reading is making interior connections that can be applied in exterior directions. I didn’t know I could take as much time as I needed in order to get the most out of what I was reading.

So I stopped reading.

My second mistake was thinking that education would degrade my creativity and demoralize my spirit by making me swallow alien propaganda.

So rather than feeling impoverished by my illiteracy or feeling ashamed enough by it to change, I was actually proud to be non-educated.

Ironically, this attitude locked out my best chance to figure out who I was on my own, which was the only way I was comfortable doing things.

What I was left with was worse than nothing.

By rejecting the lessons in great literature, I deprived myself encouragement that comes with identifying one’s own problems in others, and I denied myself balance against my own error, so that I actually became more resentful, more isolated and more self-destructive.

Then it happened: my free will seized.

I became a fixed man in a moving world.

But at the point where I should have died I got swept into something I still don’t understand 20 years later in which I emerged still doubting and still troubled and still bereft, but no longer resisting my own conscience.

III. The Importance of Original Offense

It was during my recovery that I learned about the original offense.

The original offense is the knowledge that our conscience is already programmed when we first meet it. The original offense is the expectation upon us when we first know our conscience to accept the fact that we are not our own authors.

From the beginning, I knew there was someone else’s handwriting on my deepest inside guide. I knew the handwriting belonged to the author of right and wrong. And I resented it.

What I didn’t know was that it was okay to feel offended.

It’s true of course that we ought to be perfectly confident that the author who has informed our conscience so impeccably with the laws of life must be supremely good and supremely just.

Still, I couldn’t help feeling indignant that the writing is there at all.

After all, it was my own conscience.

It was this indignity that prevented me from listening to my own inner voice. It was this indignity that made my interior reason sound to me like treason.

So during my recovery from alcoholism and during my discovery of faith in unseen things I came to a point of no return concerning my conscience, in which I had to admit that I had no choice.

I could either listen to my conscience and suffer a life of meaning, or I could ignore my conscience and suffer a living death.

While I had survived leading a dead life during my first chance when I was intoxicated by the illusion that I was making free choices, it was no longer possible for me to survive that way once I tasted the real freedom of belief.

And once I surrendered to the occupying author of my conscience, all of the other barriers to my education disappeared.

I admitted for the first time that my best thinking had brought me to ruin. I put my pride aside about what I thought I knew, and I tried to learn.

I began to read. I began to study. I began to listen. I wrote things down I wanted to remember. I discovered an appetite for learning that I had never known before, and it made me feel as young and tough as a teenager.

I was a new man, full of the old man, but with a whole life’s worth of room to grow.

And still there are many things about my own story that I don’t know.

IV. Hard Knocks Are Overrated

Every semester I tell my students that the older they get, the more responsible they are for their own education.

They want to tell me about some bad teacher who’s crossed them or some busy circumstance that’s interfered with study or some bad DNA that’s prevented them from being smart students.

I tell them that regardless of what insecurities haunt them and regardless of what unfairness happens to them they are still responsible for knowing everything essential about themselves and everything essential about their world.

It is an offense to some of them for sure, just as it was an offense to me.

But the ideas that I have now about who I am and where I came from and where I am going and why I am here are precisely because I endured what offended me and accepted the fact that there was no way to win by fighting it.

These ideas I have now about my origin and my identity and my destiny and my purpose took a long time to come to me.

I think of the people I wounded in the name of nihilism and the people I abandoned in the name of narcissism and the people I betrayed in the name of free will. Some of them I have been unable to make amends to because they’re out of range.

But it is not necessary to endure the bruises of experience and suffer the violence of self-destructiveness to find authentic ideas to live by. There are bloodless short cuts. Faith is one. Service is another. Education is the mother of both.

Education makes the heart conscious of the suffering of others. Education fills the heart’s holes with soul. Education makes the spirit receptive to grace.

But these are just words on a page.

V. The School of Self Education

If you were to ask me exactly what turned me around 20 years ago I might tell you that I went through a conversion. But that would just be a term. I might tell you that I was given a second chance. But that would be a cliché.

The remarkable thing about what happened to me is education knew what I needed to know even though I was convinced that I needed to know nothing from education.

I hope it goes without saying that I am not talking anymore about grammar or math or history.

Education exists for a purpose. There is only so much energy that we have. There is only so much vision that we have. And there are only so many chances that we have.

There is simply not enough of life or sight in any of us to get to the Promised Land without a guide.

So what I had to do as an adult with my education behind me is what many people must do as adults with their education behind them.

I had to go to school all over again.

Just as the body can be taught to do something highly specialized and completely unnecessary to survival such as hitting a round ball with a round bat squarely merely through instruction and repetition, so too the mind be taught to hit deep thought through education.

Just as the heart can be taught unnatural actions such as generosity or patience through the pursuit of friendship, so too the mind can learn complicated truths through the cultivation of education.

This is not to be confused with the continuing education one gets at work, although professional courses that tune up practitioners to the changes in thinking and approach in their fields certainly can achieve some of the same goals as self-education.

Nor is self-education to be confused with everyday observations of experience or everyday adjustments of interactions that are more reaction to outside events than an internal strategy to learn about meaning, even if observation and adjustment are important factors in self-education.

Instead this is about faith that your soul knows where to go.

Follow it.

You do that by letting go of what you don’t know so that education can show you where to grow.

February 24, 2013

The Revelation of Education

NEW YORK – Growing up in Chicago, nobody taught me to be an education hater.

Yes, my teachers presumed that grammar and math and history were my good fortune to learn. And I hated all that instruction about nothing.

But it wasn’t my teachers who taught me to loathe learning, because I despised extra-curricular education more.

Yes, my father presumed that baseball was my destiny and he coached into me hitting philosophies and fielding fundamentals and training disciplines. And I hated all that exercise about nothing.

But it wasn’t my dad the coach who fueled my reproach for learning, because I despised social education still more.

Yes, my peers presumed that my idea of success was acceptance, and that my idea of happiness was popularity. And I hated all that posturing about nothing.

But it wasn’t my friends who chilled my yearning for learning, because what I despised most of all was self-education.

I despised self-education for the same reason that I despised all education: I was always offended by people telling me what to do.

It all started from my earliest acquaintance with my conscience; I never wanted to listen to my own voice.

As a result, I grew up learning nothing and believing nothing and seeing nothing wrong with knowing nothing.

No doubt my experience is difficult to relate to for many people. But I’ve found that the place I wound up as a consequence is not so different from the place other baby busters wound up, with their midlife ahead of them and their education behind them.

There I was, a man near 30. I was a husband and a father, a nine-to-fiver and an every-night partier. I had no knowledge about life-changing thought. I had every intention to lead the unexamined life by living through the body.

When the anxiety hit, I swiped back with gin. When love wouldn’t trade, I let it fade. When I became incoherent to myself I pursued oblivion. But I could only go on so long being my own unhappiness.

What came next should never have happened to a man like me. But it did. And it was all for the purpose of my education.

II. When Free Will Seizes

It doesn’t matter that my issue with education in Chicago was one of my will and not one of my ability, because I wouldn’t have been able to distinguish the difference back then anyway.

Had someone told me back then, as I tell students now, that the primary goal of education is to learn how you learn, it wouldn’t have mattered to me, although I probably would have paid a bit more attention, being a narcissist, had someone pointed out that I was the real subject of the lesson and not the grammar or the math or the history.

The goal of education is to give us skills to cure injustice, to appease conflict and to endure suffering so that we can sustain life-long bonds and protect people entrusted to us and serve people in need. To develop these skills we must learn how to be critical thinkers and careful observers and radical humanitarians.

Try teaching that to me back then.

My problem in school and my problem on the ball field and my problem at the park after dark with my binge friends had a single source: I didn’t know myself.

As a result, I had the wrong idea about what learning was, and I had the wrong idea about what learning does.

My first mistake was thinking that education was something external that I had to reach for and secure with great labor, instead of thinking of education as something internal that I merely had to switch on to activate.

I compounded that mistake by thinking that there was only one way to learn – the way the particular teacher taught, or the way particular classmates thought.

For example, I had the wrong idea that reading was something that was supposed to come easily and quickly to everyone, and that if I did not absorb a story fully on the first take, it was because I was not smart enough to understand it.

I didn’t know that the goal of reading is making interior connections that can be applied in exterior directions. I didn’t know I could take as much time as I needed in order to get the most out of what I was reading.

So I stopped reading.

My second mistake was thinking that education would degrade my creativity and demoralize my spirit by making me swallow alien propaganda.

So rather than feeling impoverished by my illiteracy or feeling ashamed enough by it to change, I was actually proud to be non-educated.

Ironically, this attitude locked out my best chance to figure out who I was on my own, which was the only way I was comfortable doing things.

What I was left with was worse than nothing.

By rejecting the lessons in great literature, I deprived myself encouragement that comes with identifying one’s own problems in others, and I denied myself balance against my own error, so that I actually became more resentful, more isolated and more self-destructive.

Then it happened: my free will seized.

I became a fixed man in a moving world.

But at the point where I should have died I got swept into something I still don’t understand 20 years later in which I emerged still doubting and still troubled and still bereft, but no longer resisting my own conscience.

III. The Importance of Original Offense

It was during my recovery that I learned about the original offense.

The original offense is the knowledge that our conscience is already programmed when we first meet it. The original offense is the expectation upon us when we first know our conscience to accept the fact that we are not our own authors.

From the beginning, I knew there was someone else’s handwriting on my deepest inside guide. I knew the handwriting belonged to the author of right and wrong. And I resented it.

What I didn’t know was that it was okay to feel offended.

It’s true of course that we ought to be perfectly confident that the author who has informed our conscience so impeccably with the laws of life must be supremely good and supremely just.

Still, I couldn’t help feeling indignant that the writing is there at all.

After all, it was my own conscience.

It was this indignity that prevented me from listening to my own inner voice. It was this indignity that made my interior reason sound to me like treason.

So during my recovery from alcoholism and during my discovery of faith in unseen things I came to a point of no return concerning my conscience, in which I had to admit that I had no choice.

I could either listen to my conscience and suffer a life of meaning, or I could ignore my conscience and suffer a living death.

While I had survived leading a dead life during my first chance when I was intoxicated by the illusion that I was making free choices, it was no longer possible for me to survive that way once I tasted the real freedom of belief.

And once I surrendered to the occupying author of my conscience, all of the other barriers to my education disappeared.

I admitted for the first time that my best thinking had brought me to ruin. I put my pride aside about what I thought I knew, and I tried to learn.

I began to read. I began to study. I began to listen. I wrote things down I wanted to remember. I discovered an appetite for learning that I had never known before, and it made me feel as young and tough as a teenager.

I was a new man, full of the old man, but with a whole life’s worth of room to grow.

And still there are many things about my own story that I don’t know.

IV. Hard Knocks Are Overrated

Every semester I tell my students that the older they get, the more responsible they are for their own education.

They want to tell me about some bad teacher who’s crossed them or some busy circumstance that’s interfered with study or some bad DNA that’s prevented them from being smart students.

I tell them that regardless of what insecurities haunt them and regardless of what unfairness happens to them they are still responsible for knowing everything essential about themselves and everything essential about their world.

It is an offense to some of them for sure, just as it was an offense to me.

But the ideas that I have now about who I am and where I came from and where I am going and why I am here are precisely because I endured what offended me and accepted the fact that there was no way to win by fighting it.

These ideas I have now about my origin and my identity and my destiny and my purpose took a long time to come to me.

I think of the people I wounded in the name of nihilism and the people I abandoned in the name of narcissism and the people I betrayed in the name of free will. Some of them I have been unable to make amends to because they’re out of range.

But it is not necessary to endure the bruises of experience and suffer the violence of self-destructiveness to find authentic ideas to live by. There are bloodless short cuts. Faith is one. Service is another. Education is the mother of both.

Education makes the heart conscious of the suffering of others. Education fills the heart’s holes with soul. Education makes the spirit receptive to grace.

But these are just words on a page.

V. The School of Self Education

If you were to ask me exactly what turned me around 20 years ago I might tell you that I went through a conversion. But that would just be a term. I might tell you that I was given a second chance. But that would be a cliché.

The remarkable thing about what happened to me is education knew what I needed to know even though I was convinced that I needed to know nothing from education.

I hope it goes without saying that I am not talking anymore about grammar or math or history.

Education exists for a purpose. There is only so much energy that we have. There is only so much vision that we have. And there are only so many chances that we have.

There is simply not enough of life or sight in any of us to get to the Promised Land without a guide.

So what I had to do as an adult with my education behind me is what many people must do as adults with their education behind them.

I had to go to school all over again.

Just as the body can be taught to do something highly specialized and completely unnecessary to survival such as hitting a round ball with a round bat squarely merely through instruction and repetition, so too the mind be taught to hit deep thought through education.

Just as the heart can be taught unnatural actions such as generosity or patience through the pursuit of friendship, so too the mind can learn complicated truths through the cultivation of education.

This is not to be confused with the continuing education one gets at work, although professional courses that tune up practitioners to the changes in thinking and approach in their fields certainly can achieve some of the same goals as self-education.

Nor is self-education to be confused with everyday observations of experience or everyday adjustments of interactions that are more reaction to outside events than an internal strategy to learn about meaning, even if observation and adjustment are important factors in self-education.

Instead this is about faith that your soul knows where to go.

Follow it.

You do that by letting go of what you don’t know so that education can show you where to grow.

December 12, 2012

Intimacy and Original Injury

WE learn from an early age that injuries can heal.

But we suffer from our earliest experience about what injuries reveal.

And what injuries reveal is that healing is a matter of the will.

This is true for injuries we sustain ourselves and this is true for injuries caused by others.

It’s true whether we are responsible for our own injuries through neglect or recklessness, or whether others are responsible for our injuries by accident or design.

It’s true for injuries of punishment and crime.

The burden is always ours to heal.

We learn early that what heals we are able to bear.

But wounds that won’t stop hurting we are unable to endure.

So we are driven out of ourselves to find relief.

We go in search of another body to join at the bone to brace our brokenness. We pursue a new soul to fill the hole. We look for a heart that can receive our pain and make it our gain.

This is the whole goal of intimacy.

When we find it we become partners in the creation of a masterpiece that leads to new life and lasts until death.

And as brilliant as this connection is with another person, it is only a shadow of what we need from intimacy.

II. The Nature of Original Injury

The heart of suffering is injury.

And the seat of all injury is the original wound.

The original wound is the knowledge that we harm ourselves and we harm others, in spite of our best intentions, because free will is a beast too wild to tame.

This knowledge about our powerlessness over wounding ourselves and wounding others is worsened by the fact that injury and death are so closely intermingled.

As a result, many of us feel over matched.

If we are victimized we may rely on character defenses that say ‘Never again will we trust so much that we allow someone else to hurt us.’

If we self inflict emotional or psychological injury we may rely on character defects that say ‘Never again will we make someone else’s happiness more important than our own.’

We turn our focus to treating the symptoms rather than the wound.

The process shrinks our hearts.

We should say that physical injuries from disease or accidents are not under our conscious control and many times do not respond to our will to get better. Terminal disease and catastrophic injury rarely reroute their course for us. And while this pain is devastating and deadly, it must be accepted because it is outside our resolve.

But it is not acceptable to allow our spiritual injuries to go untreated. It is fatal. And it spreads death to others.

There may be good reasons why we allow spiritual wounds to go untreated.

Perhaps we don’t follow the pain to the source because we don’t know how to recognize where the pain is coming from. Perhaps we know very well where the pain is coming from and we look away from it to make it go away. Perhaps we feel there is no healing on earth that can fix what hurts us.

But if we don’t do what is necessary through confession and compassion to heal our injuries and make our welfare about the happiness of others, it makes no difference what good excuse we have for letting our heart wounds ooze.

We will be eaten alive by resentment.

If our free will is restrained by pain that prevents the amends we need to feed our growth, we have no hope.

All we have is the conventional wisdom that time heals all wounds.

And even that is hopeless.

If by time conventional wisdom means the passing of minutes with no attention spent on the quality of the elapsing moments, not only won’t time heal but time will harden our edges and chill our center. And the more time we spend diverting ourselves in denial the more we seal our wounds and sear our souls against any remedy.

So time must be converted to Things I Must Earn, such as virtue, to work against human tendencies for greed and self-seeking.

Time must be converted to Things I Must Endure, such as suffering in the service of others, to work against the human tendencies for depression and isolation.

These conversions of time are not possible without intimacy.

III. Intimacy and Injury

We all understand the thrill of going deep. It’s exciting to greet meaning on our own terms.

We all understand the rush of ecstasy. It’s freeing to float above problems with the confidence that we have good grounding.

We all understand the attraction of mutual connection. It’s liberating to express ourselves by touching someone else.

This is the obvious part of what makes intimacy so unique and so universal.

What may not be as evident is that intimacy is singularly suited for healing.

Inasmuch as healing achieves the greatest good for everyone, intimacy gains the most we can get for ourselves by giving the most we can offer to someone else.

What gives intimacy its authenticity is the feeling of individuality that comes through union.

What gives intimacy its security is the feeling of well being that comes through vulnerability.

What gives intimacy its freedom is the expression of abandonment that comes through the act of commitment.

But we have terrible problems with intimacy.

We have problems finding it.

We have problems maintaining it.

We especially have problems because of it. We misuse it. We abuse it.

Most of our problems stem from a misunderstanding about what intimacy is for.

Intimacy is for love and for life. And the driving force behind intimacy is faithfulness and service.

That is not what American culture says. American culture says that intimacy is for pleasure and for profit. American culture says that the driving force behind intimacy is passion and gratification.

What. We don’t know that?

Of course intimacy is intoxicating because it’s urgent and urge-driven.

But the height of intimacy is self-giving.

Moreover, everything that is promised by intimacy is possible in monogamy. When intimacy is exclusive and longsuffering it becomes a masterpiece worthy of imitation.

We know this is true because the extraordinary familiarity we develop in monogamous intimacy continues to deepen and broaden as we persevere.

Needless to say there are no such benefits for intimacy that is reduced to something quick, casual or selfish.

Worse, when intimacy is not protected by monogamy, injury invariably damages the relationship and breaks the bond that intimacy creates. And the split is never clean. The split is excruciatingly uneven. Bone and heart tissue rip away as well.

But we must not lose faith in intimacy.

If we do our wounds win.

IV. The Hierarchy of Intimacy

We are used to thinking of intimacy that satisfies the passion of the body.

We are used to thinking of intimacy that meets the emotional needs of the mind.

We are used to thinking of intimacy that consummates the deep desire of the soul.

But intimacy is more than the three parts of a person coming together as a whole.

Intimacy is the communion of mutual self-giving for life.

And although we may not think of everyday intimacy in such an elevated way, it is only because we are not used to thinking of everyday life in such an elevated way.

We are sense-bound people, after all, and nothing releases the senses like intimacy.

But there is a realm we all experience that becomes eerily real the less we take in with our eyes and ears.

Few of us would describe our interaction with this life outside the senses as intimate unless we are among those few who have experienced its raptures.

More often we describe our interaction with the life of the spirit as ethereal or elusive precisely because the realm outside the body seems so hard to see and taste and smell and hear. We rarely would describe our intercourse with the divine life as a high or a rush or a charge as we would describe intercourse with our soul mate.

But we can have the same benefits of intimacy in our faith life as we do in our married life if we give ourselves to the God of our understanding as intimately as we give ourselves to our spouse.

It’s true that we may not feel the rush of arousal or the swelling of passion or the relief of release in our intimacy with God that we do in our intimacy with our spouse.

But it is also true that intimacy transcends nerve ends.

And it is intimacy at this level where there is not only an unconditional love that death cannot sever but also a true remedy for the original wound.

It is intimacy at this level that not only heals injury we cannot undo but also reveals the healer who makes all things new.

Ultimate Intimacy

WE learn from an early age that injuries can heal.

But we suffer from our earliest experience about what injuries reveal.

And what injuries reveal is that healing is a matter of the will.

This is true for injuries we sustain ourselves and this is true for injuries caused by others.

It’s true whether we are responsible for our own injuries through neglect or recklessness, or whether others are responsible for our injuries by accident or design.

It’s true for injuries of punishment and crime.

The burden is always ours to heal.

We learn early that what heals we are able to bear.

But wounds that won’t stop hurting we are unable to endure.

So we are driven out of ourselves to find relief.

We go in search of another body to join at the bone to brace our brokenness. We pursue a new soul to fill the hole. We look for a heart that can receive our pain and make it our gain.

This is the whole goal of intimacy.

When we find it we become partners in the creation of a masterpiece that leads to new life and lasts until death.

And as brilliant as this connection is with another person, it is only a shadow of what we need from intimacy.

II. The Nature of Original Injury

The heart of suffering is injury.

And the seat of all injury is the original wound.

The original wound is the knowledge that we harm ourselves and we harm others, in spite of our best intentions, because free will is a beast too wild to tame.

This knowledge about our powerlessness over wounding ourselves and wounding others is worsened by the fact that injury and death are so closely intermingled.

As a result, many of us feel over matched.

If we are victimized we may rely on character defenses that say ‘Never again will we trust so much that we allow someone else to hurt us.’

If we self inflict emotional or psychological injury we may rely on character defects that say ‘Never again will we make someone else’s happiness more important than our own.’

We turn our focus to treating the symptoms rather than the wound.

The process shrinks our hearts.

We should say that physical injuries from disease or accidents are not under our conscious control and many times do not respond to our will to get better. Terminal disease and catastrophic injury rarely reroute their course for us. And while this pain is devastating and deadly, it must be accepted because it is outside our resolve.

But it is not acceptable to allow our spiritual injuries to go untreated. It is fatal. And it spreads death to others.

There may be good reasons why we allow spiritual wounds to go untreated.

Perhaps we don’t follow the pain to the source because we don’t know how to recognize where the pain is coming from. Perhaps we know very well where the pain is coming from and we look away from it to make it go away. Perhaps we feel there is no healing on earth that can fix what hurts us.

But if we don’t do what is necessary through confession and compassion to heal our injuries and make our welfare about the happiness of others, it makes no difference what good excuse we have for letting our heart wounds ooze.

We will be eaten alive by resentment.

If our free will is restrained by pain that prevents the amends we need to feed our growth, we have no hope.

All we have is the conventional wisdom that time heals all wounds.

And even that is hopeless.

If by time conventional wisdom means the passing of minutes with no attention spent on the quality of the elapsing moments, not only won’t time heal but time will harden our edges and chill our center. And the more time we spend diverting ourselves in denial the more we seal our wounds and sear our souls against any remedy.

So time must be converted to Things I Must Earn, such as virtue, to work against human tendencies for greed and self-seeking.

Time must be converted to Things I Must Endure, such as suffering in the service of others, to work against the human tendencies for depression and isolation.

These conversions of time are not possible without intimacy.

III. Intimacy and Injury

We all understand the thrill of going deep. It’s exciting to greet meaning on our own terms.

We all understand the rush of ecstasy. It’s freeing to float above problems with the confidence that we have good grounding.

We all understand the attraction of mutual connection. It’s liberating to express ourselves by touching someone else.

This is the obvious part of what makes intimacy so unique and so universal.

What may not be as evident is that intimacy is singularly suited for healing.

Inasmuch as healing achieves the greatest good for everyone, intimacy gains the most we can get for ourselves by giving the most we can offer to someone else.

What gives intimacy its authenticity is the feeling of individuality that comes through union.

What gives intimacy its security is the feeling of well being that comes through vulnerability.

What gives intimacy its freedom is the expression of abandonment that comes through the act of commitment.

But we have terrible problems with intimacy.

We have problems finding it.

We have problems maintaining it.

We especially have problems because of it. We misuse it. We abuse it.

Most of our problems stem from a misunderstanding about what intimacy is for.

Intimacy is for love and for life. And the driving force behind intimacy is faithfulness and service.

That is not what American culture says. American culture says that intimacy is for pleasure and for profit. American culture says that the driving force behind intimacy is passion and gratification.

What. We don’t know that?

Of course intimacy is intoxicating because it’s urgent and urge-driven.

But the height of intimacy is self-giving.

Moreover, everything that is promised by intimacy is possible in monogamy. When intimacy is exclusive and longsuffering it becomes a masterpiece worthy of imitation.

We know this is true because the extraordinary familiarity we develop in monogamous intimacy continues to deepen and broaden as we persevere.

Needless to say there are no such benefits for intimacy that is reduced to something quick, casual or selfish.

Worse, when intimacy is not protected by monogamy, injury invariably damages the relationship and breaks the bond that intimacy creates. And the split is never clean. The split is excruciatingly uneven. Bone and heart tissue rip away as well.

But we must not lose faith in intimacy.

If we do our wounds win.

IV. The Hierarchy of Intimacy

We are used to thinking of intimacy that satisfies the passion of the body.

We are used to thinking of intimacy that meets the emotional needs of the mind.

We are used to thinking of intimacy that consummates the deep desire of the soul.

But intimacy is more than the three parts of a person coming together as a whole.

Intimacy is the communion of mutual self-giving for life.

And although we may not think of everyday intimacy in such an elevated way, it is only because we are not used to thinking of everyday life in such an elevated way.

We are sense-bound people, after all, and nothing releases the senses like intimacy.

But there is a realm we all experience that becomes eerily real the less we take in with our eyes and ears.

Few of us would describe our interaction with this life outside the senses as intimate unless we are among those few who have experienced its raptures.

More often we describe our interaction with the life of the spirit as ethereal or elusive precisely because the realm outside the body seems so hard to see and taste and smell and hear. We rarely would describe our intercourse with the divine life as a high or a rush or a charge as we would describe intercourse with our soul mate.

But we can have the same benefits of intimacy in our faith life as we do in our married life if we give ourselves to the God of our understanding as intimately as we give ourselves to our spouse.

It’s true that we may not feel the rush of arousal or the swelling of passion or the relief of release in our intimacy with God that we do in our intimacy with our spouse.

But it is also true that intimacy transcends nerve ends.

And it is intimacy at this level where there is not only an unconditional love that death cannot sever but also a true remedy for the original wound.

It is intimacy at this level that not only heals injury we cannot undo but also reveals the healer who makes all things new.

November 9, 2012

Poverty Values

NEW YORK — It’s a rare American who wakes up praising poverty.

Those of us who are poor fight it. We hide it. We tell poverty to stop following us. We tell poverty that we’re going to leave it as soon as we get more property.

We even sell ourselves out to defeat it.

This makes us Americans poor ambassadors of poverty.

It hardens us against what makes poverty enduring and what makes poverty universal and what makes poverty enriching.

Of course we are not talking about the kind of abject poverty that threatens people’s lives.

We are not talking about our moral duty of preferential treatment for the poor.

Obviously, we commend our great social services and the selfless missions of history and the heroic volunteers with love-of-neighbor in their hearts who minister to the needy.

What we are talking about is demonizing poverty and glorifying property in the name of the American Dream.

By poverty we mean the kind that everyone knows but that no one acknowledges – the bareness we are born with and the nakedness we take to the grave.

It’s upon this poverty that we pile our dissatisfaction with the material life and our disappointment with the reception of others and our restlessness with ourselves.

Conversely, all the hopes we have for material fulfillment and for social acceptance and for personal peace we heap upon the day of riches, which we are certain is coming.

It’s a trap deeper than six feet.

Something inside us senses this.

We just don’t know what to do about it.

II. Free Money

Our problem with poverty is there isn’t enough money in it.

We know that the more money we have, the more life bows to us.

The more life bows to us, the more our purpose seems confirmed and the more our destiny seems like an accomplished fact.

This fits perfectly with our belief that money is our destiny.

And why not? American culture teaches us that money is the common denominator of happiness. Money is the source and the summit of the American dream.

The problem is the American Dream is more delusion than inspiration.

It is often suggested that the American Dream is to make enough money in our lifetime so that our children will enjoy a better life than we did.

But that is not the American Dream. That is the universal burden.

The real American dream is easy wealth. The real American dream is free money. The real American dream is the big lottery jackpot.

We aren’t honest about how seriously we take this dream because we know what a fantasy it represents.

We know that we can’t get something for nothing, even if all we are counting on is pure luck.

We know that in order to get a great reward we have to deserve it somehow, which takes restraint and selflessness and gratitude for the things that we already have.

We know that our real problem is not that we are miserable being poor, but that we are miserable being ourselves.

So we want a new life of power over disappointment, and pleasure over rejection, and possessions over emptiness.

We would never believe that poverty is the answer.

III. Myth and Meaning

We believe in the myth of free money so much that it has become indistinguishable from the fairy tale of Prince Charming.

We believe in the myth even though we know that pots of gold don’t materialize at the end of rainbows any more than love comes without strife and sacrifice.

So we propose a bargain to improve our odds: we promise to do good with our free money.

We promise to give away money, even if we don’t give away our money now.

We promise to be angels to others, even if we have little desire to be angels now.

We promise to be satisfied, even if we are rarely satisfied now.

This is where our deceit tells the truth about us.

By confessing the distance between the people we would be with more money and the people we are now with less money, we are admitting to the world where we draw the line.

We draw the line precisely where we live life today.

If we are capable of being better people with money, then we are capable of being better people without money.

We know this because no one can forbid us from doing good except ourselves. We know this because no one can force us do good except ourselves.

The fact that we choose to stay the way we are testifies that we are free agents. It does not testify that we are restricted by poverty.

It does not suggest that we would be better with money.

Money uses all of its advantages to insulate us from the manual labor of virtue building. Money tells us that hard work is for people who haven’t made it yet.

All we can imagine is how much better we’d be with the money of our dreams.

The truth is with dream money, we would wake up the same people as we are now, except we would be a little shittier.

IV. The Spirit of Poverty

There are enough passages in the Bible about the importance of poverty to write four seasons of sermons.

Even if we just focus on the New Testament, and even if we zero-in only on the hero of that collection books, we still find many more teachings about the value of poverty than we could absorb in a single sitting.

It’s impossible to miss them.

The teachings of Jesus in the New Testament about poverty scandalized the people of his time who considered wealth the leading indicator of character just as much as his teachings scandalize the people of our time.

His point is not that poverty is a virtue in itself, or that poverty is some kind of favored poetic alternative to commercialism, or that poverty is some preferred ascetic power over impulses.

His point is that poverty is a person.

Not only does Jesus embody poverty himself as a man who was born poor and who wanders about in his prime homeless, jobless and possession-less, but he elevates the humanity of each poor person he heals.

He tells a rich man who has led a moral life to sell all he has and give it to the poor if he wants to be perfect.

He tells a poor woman who gives a little bit that her donation is worth more than a rich man who gives a lot.

And in one of Jesus’ most difficult teachings that continues to tongue tie theologians 2000 years later, he sits on a mountain speaking to the dregs of his generation who longed for an end to oppression and a restoration of the glory that Israel had under the reign of Solomon.

Jesus did not tell them to rise up and overthrow the forces of injustice that produce poverty. Jesus did not recommend them to a strong work ethic and encourage them to achieve their destiny of financial independence.

He told them Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom heaven.

It is such a momentous message that generations of religious women and men continue to take vows of poverty as a path to spiritual purity, not because poverty is an end in itself, but because poverty is a sacrifice of love.

The idea became so important in the Renaissance that poverty was given a special place on the Wheel of Fortune between war and humility.

What we take from this is that poverty is not something to escape or something to vanquish. It is something to accept that on its face seems unacceptable, like so much else that is counter intuitive in the life of meaning.

Just as empowerment comes through surrender and just as gain comes through giving, enrichment comes through poverty.

Poverty means acknowledging our limitations and admitting our neediness and confessing our interdependence on others.

Poverty means accepting our pain and brokenness so that we might soften the suffering of others through compassion and service.

Most of all poverty means faith in a fortune that no money can buy.

October 16, 2012

The Fuel of Renewal

Everyone who has ever overused knows that it creates more pain than it takes away.

It’s true with booze.

It’s true with food.

It’s true with meds that soothe our mood.

But that doesn’t matter to us abuse artists.

Our pattern is a perfect circle: the minute we feel the ill effects of overuse, we overuse so that we no longer feel.

Our pattern is a perfect circle: the minute we feel the ill effects of overuse, we overuse so that we no longer feel. And once we no longer feel, we do whatever we want, even though we know it will produce more ill effects.

The problem is that no one can overcome a circle.

The problem is not so much that there is something evil about unchecked alcoholic intoxication or that there is something awful about over-indulging an appetite or that there is something immoral about incessantly knocking back pills to cope with the common day.

The fact is too many people enjoy alcohol with impunity and too many people eat unburdened and too many people have drug stores in their medicine cabinets without becoming junkies for addiction to be merely about the substance itself being abused.

The deeper thing that gives substance abuse its sting is the futility of fueling a sick life that no drug can save.

The hell of addiction is not a heavy hand with the medicine, or an overdoing of the fuel. The hell of addiction is having hope in a life that is already over.

The surest way to know that a life is over is to start a new life and to see in retrospect what was never conceivable while it was happening.

But let’s be clear here that a life which perverts the soul’s need to enjoy nourishment or a life that prevents a mind’s need to renew its beliefs or a life that punishes a heart’s need to love is not a life worth living.

It’s a live worth leaving.

We who overuse are the last ones to see this.

Because we are so addicted to overusing and because we are so limited in our circular thinking and because we are so numb to the impulses of our imminent death, it never occurs to us that our diseased lives need to be buried.

We need not only a second chance at life but also a new energy source that will allow us to thrive in the time we have left.

This does not happen easily.

The recovery from addiction and the necessity to live off an unproven energy source has as much momentum going for it as cutting America’s dependence on foreign oil and switching to sustainable fuel.

The cutting of the dependence seems so defeating, and the prospect of some softer leaner sober power seems so demeaning that it’s easy to diminish the whole proposal as conformist weakness.

But cheer up: the mission couldn’t be more revolutionary.

The mission is change or die.

If we choose life, the good news is that the new energy source for our second chance life is already within us.

II. Signs of a dying life

I tell my undergraduates each semester that we won’t know for sure how great living writers are until they die, and we can determine how they hold up against the rest of history.

I like to watch the students’ reaction.

Death is an unusual prerequisite for establishing greatness in our culture, because we Americans enshrine people in the hall of fame before their reign is finished, and because we Americans are so prejudiced against the heroes of history who make our accomplishments appear pedestrian.

The students invariably laugh or look at each other as though I can’t be serious.

But I am serious.

Death makes clear what life distorts.

We all have a first chance in life. And when our first chance is not lived with love and not lived with service and not lived with purpose, it dies.

It doesn’t matter how much balm we put on a gangrenous foot. It’s not taking us anywhere but the grave.