Jacqueline Winspear's Blog

August 4, 2014

How Life Would Change

For those of you who are new to this blog - I started it almost three years ago, to honor the generation of women who came of age in the Great War, and whose lives were changed by that war. I always felt there was much to learn from them. I stopped writing the blog when my father fell ill in early 2012, and although I have promised to pick it up again along the way, it never seemed to be the right time. Now it is. Today marks the anniversary of Britain's declaration of war in 1914, so it seemed a good moment to come back to the blog, and to write about an extraordinary generation of women.

August 4th, 2014

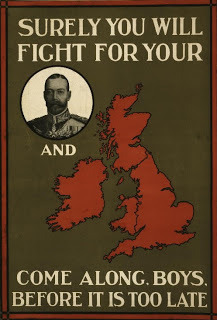

Today is the 100th anniversary of the day Britain declared war on German in 1914. For several days people had been out on the streets, waiting for an announcement, as speculation increased. Already soldiers from the regular army were being deployed to the Channel ports, and trains were delayed and canceled to facilitate their travel as the plan for general war in Europe awaited action. There were growing crowds waiting outside Buckingham Palace for news, or who made their way to St. Paul's Cathedral, and more than a few at Downing Street. Britain was in the midst of a long, hot summer when the most pressing issues facing Parliament had hitherto been the economy, "the Irish question" and the fight for suffrage being waged by Britain's women.

How could anyone have imagined the extent to which life would change over the coming years of war? How could they know that so many young men would die on a foreign field, and that what became known as The Great War would, in fact, lead to another war - it seems there was only a ceasefire between 1918 and 1938/39. Would they have believed that the Great War would herald changes in every sphere - in society, in international law, medicine, geopolitics, technology, telecommunications, global power, travel, and so on? I am reprinting here, below, an essay I wrote that was published recently in The Daily Beast - it's a personal recollection of a few of those women who came of age in that terrible war. They were elderly when I was a child, and I often wonder, now, how they felt on August 4th, 1914, when their country went to war.

I was wearing my best dress, best shoes, and my hair was braided with ribbon. At four years old, I was only going to have tea with a neighbor, so I might have seemed a little overdressed – but my mother was well aware that the neighbor’s last intimate experience of childhood was her own in Edwardian England. In 1959, I was the only child in our hamlet, so I was in some demand among the ladies of a certain age who lived alone, having never married. I would sit at table with my boiled egg and toast, or a small cheese and cucumber sandwich and a scone with butter and jam, and I would answer their questions. And because I was a curious child, I had questions of my own. Each of those women had a sepia photograph on the mantelpiece, of a young man in uniform. And I remember the answer, when I asked about the man. “Oh, that was my sweetheart. He died in the Great War.” I already knew about this “great war” because I’d been told that my grandfather’s ailments were all due to the same event. Granddad had been wounded, shell-shocked and gassed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and it was my questions about him that ignited a lifelong interest in the effects of war and its aftermath – and in particular, the changes wrought by that conflict on the lives of women. A young woman in pre-WW1 Britain would likely expect her life to follow that of her mother and grandmother. Dependent her “station” in life, she might work in a factory, in domestic service, a shop, or in an office. If she were from the middle or upper classes, she would remain at home until marriage, hopefully before the age of twenty-one. Women’s lives were as restricted as their clothing, though Britain’s suffragettes were considered the most vociferous. Then war was declared in 1914. By the time the Armistice was signed in 1918, a young British woman aged 16-32 stood only a one-in-ten chance of marriage. The 1921 census revealed that there were two million “surplus” women of marriageable age, a statistic that led to publication of a pamphlet, “The Problem of the Surplus Women.” That might appear amusing, but a generation had endured a devastating human tragedy. It must have seemed liberating to my 18-year-old grandmother, Clara - she was living away from home in quarters close to the Woolwich Arsenal, working with volatile explosives. She was earning “good money” for a woman, though it was half that paid to a man doing the same job. The wage gave Clara and her women-friends a measure of independence – on a day off they could pretty much do as they liked. In the years 1914-18, women flooded into the workplace to take on the toil of men conscripted to fight. No field of endeavor was left untouched by a woman’s hand – they built ships, aircraft, tanks. They made munitions. They drove trains and buses and became mechanics. They worked overseas as nurses, ambulance drivers, and in military support roles. They buried the dead, delivered the coal and the milk, and women police auxiliaries pounded the streets. Some fifty thousand worked in the Secret Service. Women were now in very visible roles, not hidden in factories, or offices, or working at home. After the euphoria of the Armistice gave way to a deep collective depression, it was clear that life would not return to “normal” – especially for a woman. Certainly there were those who were married, but many floundered, living solitary lives. But others blazed a trail, realizing they alone had to bear responsibility for their financial security, that they must build community or become invisible, and that they had to nurture relationships to sustain them in old age. Women became teachers and scientists, they worked in business, became justices of the peace and entered politics, and if they couldn’t find work, they made it. The time between the wars became the golden era of the British woman novelist – there’s a job you can do at home with no training! I believe an archetype was born in those years, that of the doughty British woman – proud, opinionated, but with a heart of gold. I knew her – she was one of the ladies who invited me to tea because she ached to have children in her life. The chance of becoming a mother had died when she lost her sweetheart in the Great War.

August 4th, 2014

Today is the 100th anniversary of the day Britain declared war on German in 1914. For several days people had been out on the streets, waiting for an announcement, as speculation increased. Already soldiers from the regular army were being deployed to the Channel ports, and trains were delayed and canceled to facilitate their travel as the plan for general war in Europe awaited action. There were growing crowds waiting outside Buckingham Palace for news, or who made their way to St. Paul's Cathedral, and more than a few at Downing Street. Britain was in the midst of a long, hot summer when the most pressing issues facing Parliament had hitherto been the economy, "the Irish question" and the fight for suffrage being waged by Britain's women.

How could anyone have imagined the extent to which life would change over the coming years of war? How could they know that so many young men would die on a foreign field, and that what became known as The Great War would, in fact, lead to another war - it seems there was only a ceasefire between 1918 and 1938/39. Would they have believed that the Great War would herald changes in every sphere - in society, in international law, medicine, geopolitics, technology, telecommunications, global power, travel, and so on? I am reprinting here, below, an essay I wrote that was published recently in The Daily Beast - it's a personal recollection of a few of those women who came of age in that terrible war. They were elderly when I was a child, and I often wonder, now, how they felt on August 4th, 1914, when their country went to war.

I was wearing my best dress, best shoes, and my hair was braided with ribbon. At four years old, I was only going to have tea with a neighbor, so I might have seemed a little overdressed – but my mother was well aware that the neighbor’s last intimate experience of childhood was her own in Edwardian England. In 1959, I was the only child in our hamlet, so I was in some demand among the ladies of a certain age who lived alone, having never married. I would sit at table with my boiled egg and toast, or a small cheese and cucumber sandwich and a scone with butter and jam, and I would answer their questions. And because I was a curious child, I had questions of my own. Each of those women had a sepia photograph on the mantelpiece, of a young man in uniform. And I remember the answer, when I asked about the man. “Oh, that was my sweetheart. He died in the Great War.” I already knew about this “great war” because I’d been told that my grandfather’s ailments were all due to the same event. Granddad had been wounded, shell-shocked and gassed at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and it was my questions about him that ignited a lifelong interest in the effects of war and its aftermath – and in particular, the changes wrought by that conflict on the lives of women. A young woman in pre-WW1 Britain would likely expect her life to follow that of her mother and grandmother. Dependent her “station” in life, she might work in a factory, in domestic service, a shop, or in an office. If she were from the middle or upper classes, she would remain at home until marriage, hopefully before the age of twenty-one. Women’s lives were as restricted as their clothing, though Britain’s suffragettes were considered the most vociferous. Then war was declared in 1914. By the time the Armistice was signed in 1918, a young British woman aged 16-32 stood only a one-in-ten chance of marriage. The 1921 census revealed that there were two million “surplus” women of marriageable age, a statistic that led to publication of a pamphlet, “The Problem of the Surplus Women.” That might appear amusing, but a generation had endured a devastating human tragedy. It must have seemed liberating to my 18-year-old grandmother, Clara - she was living away from home in quarters close to the Woolwich Arsenal, working with volatile explosives. She was earning “good money” for a woman, though it was half that paid to a man doing the same job. The wage gave Clara and her women-friends a measure of independence – on a day off they could pretty much do as they liked. In the years 1914-18, women flooded into the workplace to take on the toil of men conscripted to fight. No field of endeavor was left untouched by a woman’s hand – they built ships, aircraft, tanks. They made munitions. They drove trains and buses and became mechanics. They worked overseas as nurses, ambulance drivers, and in military support roles. They buried the dead, delivered the coal and the milk, and women police auxiliaries pounded the streets. Some fifty thousand worked in the Secret Service. Women were now in very visible roles, not hidden in factories, or offices, or working at home. After the euphoria of the Armistice gave way to a deep collective depression, it was clear that life would not return to “normal” – especially for a woman. Certainly there were those who were married, but many floundered, living solitary lives. But others blazed a trail, realizing they alone had to bear responsibility for their financial security, that they must build community or become invisible, and that they had to nurture relationships to sustain them in old age. Women became teachers and scientists, they worked in business, became justices of the peace and entered politics, and if they couldn’t find work, they made it. The time between the wars became the golden era of the British woman novelist – there’s a job you can do at home with no training! I believe an archetype was born in those years, that of the doughty British woman – proud, opinionated, but with a heart of gold. I knew her – she was one of the ladies who invited me to tea because she ached to have children in her life. The chance of becoming a mother had died when she lost her sweetheart in the Great War.

Published on August 04, 2014 01:30

February 10, 2012

The Singleton Strikes Back!

An op-ed piece in the New York Times a couple of weeks ago was centered on the fact that more people are living alone than ever before, with the USA actually lagging behind Europe in the number of singletons making their way in the world without a partner at their side. In fact, the author, Erik Klinenberg, says "singleton" is his word, but I could have sworn Helen Fielding arrived there first with the inimitable Bridget Jones. About ten years ago, Meghan Daum wrote a similar article for the Los Angeles Times, when the 2000 census report was published, showing a rise in the number of people living alone. "And you can bet most of those people are women," she said.

This sort of observation is far from new, as readers of this blog know. A generation of British women lived alone following the end of the Great War, and were even the subject of a 1921 pamphlet entitled, "The Problem of the Surplus Women." As I said in my introduction to the blog, when I launched it last year (click on the Introduction to the Blog link on the right if you haven't read it), I've been collecting books for and by this generation for a long time now, so it's time to break out one of my favorites – interestingly enough, written by an American author, and published in 1935. Live Alone and Like It by Marjorie Hillis is a fun read – I have an original copy, but it was republished in 2008. I'll be looking at similar books in future posts, but let's consider some sage words from Live Alone and Like It, which the author described as being "A Guide for the Extra Woman."

Solitary Refinement is the title of the first chapter – and it sets the tone for the rest of the book, though the author is a bit dismissive of the "lonely hearts" types and says that, "There is a technique about living alone successfully … whether you view your one-woman ménage as Doom or Adventure (and whether you are twenty-six or sixty-six), you need a plan, if you are going to make the best of it." Ah yes, a plan for singlehood. If you read Singled Out, recommended in an earlier post, you'll know that many women in post-WW1 Britain definitely made the best of it, if not the most of it, with some choosing singlehood even when the opportunity for marriage presented itself. Hillis, though, suggests, " … the basis of successful living alone is determination to make it successful.." With that in mind, here are a few of the chapter headings:

Who do you think you are?When A Lady Needs A FriendYour Leisure, If AnyThe Great Uniter

That sentiment behind first chapter title has inspired a whole raft of self-help books in recent years. You can almost feel Marjorie Hillis wagging her finger and warning you to "act as if …" in a very take-no-prisoners fashion. Indeed, she says it behooves the single woman to acts as if she were a duchess, or deserved nothing less than orchids. "It's a good idea," she says, "to get over the notion (if you have it) that your particular situation is a little bit worse than anyone else's." I could almost hear my grandmother saying that, starting her tirade with something along the lines of, "If you think you've got it bad, think of (add deprived person, whether the starving, the poor, the sick.)" It worked, that "just get on with it" attitude. Here's some more advice from Hillis: "Never, never, never let yourself feel that anybody ought to do anything for you. Once you become a duty you also become a nuisance." Ouch, I bet that hurt a few of her original readers, and maybe a few of her more recent followers.

Listening well, attention to matters of one's personal grooming, care with alcohol consumption, and friendship are all discussed, along with advice on the spending and saving of money. Though Live Alone & Like It was one of many such books written during the between-the-wars period, it is certainly one of the most entertaining. I've often imagined the kind of women, in that era, who might have bought this book. I think it would have made them feel not quite so alone, knowing that they were, in fact, part of a trend. Now, according to those recent articles, though there's an assumption that most single people living alone are women, increasingly men are choosing the solitary life. The interesting thing is that the dynamics are different now, when compared to those faced by Britain's "surplus women" of the 1920's – we have enhanced travel, social media, all sorts of ways to feel connected. Yet so many are choosing to live alone and please themselves.

The final page of Live Alone And Like It has a Q & A, and includes the question, "May a woman traveling alone talk to men who are fellow travelers without being introduced – especially on shipboard?Answer: If you are old enough to travel on shipboard alone, you are old enough to talk to anyone who interests you.

I like Marjorie's no-nonsense approach, though she sounds a little like the headmistress of a girls' school who has transitioned into being a life coach. Klinenberg closes his New York Times op-ed piece with the words, "All signs suggest that living alone will become even more common in the future, at every stage of adulthood and in every place where people can afford a place of their own."

Taking into account the advice of women like Marjorie Hillis, it seems that if you want to like how you live, whoever you are, whether you are alone – or, indeed, with a partner or family – an element of being able to do what you want to do, when you want to do it is an absolute necessity.

Next time: The Women Who Spied in WW1

Published on February 10, 2012 09:13

February 2, 2012

On Beauty ...

My paternal Grandmother died when I was eighteen. Her passing was particularly sad for me because, having been raised many miles from London, where she lived, I had just started college a few miles from her home, and was enjoying popping in to see her on a Saturday afternoon, or dropping by on a weeknight. She always sent me back to my digs with a packet of chocolate digestive biscuits (you Anglophiles know what those are), or she'd put a few coins in my hand, reminding me to call my parents – this from a woman who didn't have a telephone.

Nan had suffered a dreadful fall down a steep flight of stairs. Her neck was broken, so we all knew she had very little time. I remember my mother coming back from the hospital, where Nan had asked her to wash her face. My mother told me, "It was like touching a baby's skin, so soft and smooth." Her skin was something people talked about, it was so unblemished – and she had never worn make-up in her life. That life had been a hard one. She had left school – and home – at twelve to go into domestic service. Her father brought her back at thirteen when her mother died – she was needed to care for the house and three younger brothers. She married my grandfather in 1917 – a soldier who was still recovering from physical and psychological wounds sustained at the Battle of the Somme in 1916, and who was about ten years her senior. She must have been all of 18. To the day she died, she never had a washing machine, but instead completed all her household tasks with little in the way of labor saving devices (I think she had a wringer, because I remember her telling me to keep my fingers out of the way when I was a little girl and had been sent to stay for a week in the summer), yet her face remained barely lined even to her death in her late seventies.

I remember visiting Nan when I was about sixteen. I was sitting at the kitchen table when she stopped whatever she was doing – you hardly ever saw her sitting down – and took my chin in her hand and moved my face from side to side, scrutinizing me through her thick spectacles. "Time to get you some rosewater and glycerine, my girl," she said. So that afternoon we walked down to the shops, stopping in at the pharmacy. She asked for, "My usual rosewater." I watched as the pharmacist brought out two large demijohns, each marked in gold lettering. He blended equal measures of rosewater and glycerine in a plain bottle, marked the label and handed it to her. It was cheap. Much cheaper than anything else I'd been using on my skin. Nan instructed me that upon waking and before bed I was to soak a small ball of cotton wool with the solution, and to cleanse my face completely. She also told me that the sun was not my friend. Why I didn't stick with her advice, I don't know.

I thought of Nan this week, while reading an article written in 1926 for a woman's magazine, and I wondered how far we women had come, really, where care of the skin is concerned. Tackling the question of what makes a fine complexion, here's what the writer said: "To do her best for her appearance is every woman's duty towards herself and her surroundings." Her surroundings? Might my living room be doomed if I forget to moisturize? Mind you, maybe our foremothers knew there was a link between personal care and a respect for one's environment, and thus, one another. Or perhaps an untidy house leads to – heaven forbid – wrinkles!

Here's something I think I always knew, but of course in a more modern article wouldn't get a mention: the relationship between discomfort and poor skin. Those women who came of age in the early part of the last century knew this. Nan always said, "If you're bad on your feet, you're bad all the way through." I never saw her in more than one inch heels. And here's what the author of the 1926 article said: "Take for granted that your health is in trim, that you have no corns or sore feet that tend to giving your features a pained expression (the beginning of wrinkles!), and that you take a sufficient amount of daily exercise and fresh air." A suggested beauty regime followed, which I would basically describe as "soap and water" cleansing (and remember, soap was often pure of chemicals in those days), but then our writer asks the question, "Does the so-called beauty culture result in anything worth having?"

Can you imagine that question in today's magazines, when any regime seems to be worth having – and at great cost? Here's the 1926 answer: "While some of it may be useful, a great deal of it is positively harmful. The powders clog the pores, which are the 'breathers' of the skin. The paints and lipsticks encase the face so that the captivating muscular twinkling movements stop; the dimples lose the art of 'dimpling' and every kind of animation of the face disappears."

What would they say about Botox?

My grandmother's face was beautifully animated. Her smile was broad and her gray-blue eyes twinkled as a grandmother's eyes should. My father has her skin, and so does my cousin Celia, who took that sage advice and kept out of the sun. Unlike me.

Unfortunately, I never kept up with the glycerine and rosewater, though I have always tried to keep things fairly simple regarding my skin. However, after sustaining a hamstring injury some months ago, I decided to take one of those joint and ligament supplements that are supposed to help with movement. I did my research and picked a good one, but missed the observation of many reviewers that, while their joints felt better, their skin was adversely affected by the supplement. Uh-oh, if you could have seen my skin. My grandmother would have brought out the carbolic soap and a scrubbing brush! I was so miserable, and couldn't bear to be near a mirror. But Nan must have spoken to me from the beyond, because in my despair, I went online and found a bottle of Glycerine & Rosewater. Within hours of applying the water, in the way my grandmother instructed, my skin had calmed, and a few days later, there was even a bit of a glow. Now, many years after she took my adolescent chin in her hand and inspected my complexion, I know without a doubt that my grandmother knew best.

So, what tips about skincare did you learn from your mothers and grandmothers? And did you stick with them?

Published on February 02, 2012 17:59

January 19, 2012

Those Magnificent Women In Their Flying Machines

It was in 2008 that the last female veteran of WW1, passed away. Though her passing was covered by the press in both her native Britain, and in Canada, her adopted home, her death didn't seem to garner the attention that the old soldiers – men such as Harry Patch – attracted in their final years. To be sure, her experience was different – Harry Patch had marched into battle, and saw action again in the second world war. He was a remarkable man who had no truck with limelight-seeking politicians who sidled along to pay their respects at a timely moment for a photo-opportunity – good old Harry made Tony Blair wish he had kept well away.

But let's get back to Gladys Stokes.

She transferred from the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps to the newly formed Women's Royal Air Force in April 1918, where she became a Leading Aircraftswoman. Her story is a remarkable one, with early adventures that are the stuff from which books are written, however, the fact that she was an aircraftswoman – who was responsible for certain aspects of aircraft production in the Great War – fascinated me, and led me to look a little further into the lives of women who took to the air during the 1914-18 war, and in the years that followed. We've all heard of Amelia Earhart and Amy Johnson, but they were simply following in the steps of some truly intrepid flyers – and if you think that women flying combat missions is something new, then think again!

Female pilots volunteering for military service in WW1 included the following brave women: Helene Dutrieu, who made flights from Paris to check on German troop movements. Marie Marvingt flew bombing missions over Germany. A cadre of Russian aviatrix included Princess Eugenie Shakovskaya, an artillery and reconnaissance pilot, and Princess Sophie Dolgorukaya who was a pilot and an observer. Courageous women, all. Is it any surprise, then, that so many women took to the air in the post-WW1 years?

A cadre of Russian aviatrix included Princess Eugenie Shakovskaya, an artillery and reconnaissance pilot, and Princess Sophie Dolgorukaya who was a pilot and an observer. Courageous women, all. Is it any surprise, then, that so many women took to the air in the post-WW1 years?

I remember listening to recordings of women who had lived through the Great War, and whose lives were changed not only by their experiences, but by the huge shifts in society following the conflict. One woman was asked about being a "flapper" in the 1920's and in reply commented, "They called us flappers because we were like butterflies breaking out of the cocoon and flapping our wings so we could fly." And fly they did, socially, educationally – and quite literally.

While I was in England in October last year, I came across a series of articles in an annual written in the 1930's, and one just fascinated me: Flying As A Career For Girls. Here's how it begins:"For some years now flying has been a delightful hobby for wealthy girls, but at last it is beginning to take its place as providing a career for the not-so-well-off." The article points out that some fledgling female pilots prefer to be taught by their own sex, and commented on the number of flying clubs with "girl instructresses." I think I would have stuck at my flying lessons if I hadn't been instructed aloft by a half-bored pilot with a smoldering cigar that never left his mouth, even as he was shouting commands at me (and that was only my first lesson!).

The records established by women are inspiring even today. The author describes New Zealander Jean Batten as being, "The gamest little airwoman in the world." Batten was often in the news given her flying exploits, especially when she established the record of flying solo from Port Darwin, Australia to Kent, England (8,615 miles in 5 days, 18 hours, 15 minutes). Other intrepid airwomen include Harriet Quimby, the first women to fly at night, and to pilot her own 'plane across the English Channel (1912).

Other intrepid airwomen include Harriet Quimby, the first women to fly at night, and to pilot her own 'plane across the English Channel (1912).

Alys McKey Bryant, the first woman pilot in Canada (1913)

Alys McKey Bryant, the first woman pilot in Canada (1913)

And one I really love – Bessie Coleman, the first African American, man or woman, to earn a pilot's license.

And one I really love – Bessie Coleman, the first African American, man or woman, to earn a pilot's license.

There's a list that goes on and on of women's accomplishments in the field of aviation in the first 40 years of the last century. Author Dorothy Carter, herself a pilot, wrote many stories for girls and young women, generally featuring an intrepid aviatrix who could not only teach others to fly, but who could teach the men a thing or two about aircraft. I love glancing through these old stories, and reading the biographies of women who took to the skies, especially that extraordinary generation of women between the wars who seemed to be game for almost anything. And I wonder how girls and young women today could be inspired by their stories – they may not want to take to the air, but every woman, in her own way, wants to fly.

There's a list that goes on and on of women's accomplishments in the field of aviation in the first 40 years of the last century. Author Dorothy Carter, herself a pilot, wrote many stories for girls and young women, generally featuring an intrepid aviatrix who could not only teach others to fly, but who could teach the men a thing or two about aircraft. I love glancing through these old stories, and reading the biographies of women who took to the skies, especially that extraordinary generation of women between the wars who seemed to be game for almost anything. And I wonder how girls and young women today could be inspired by their stories – they may not want to take to the air, but every woman, in her own way, wants to fly.

"We swung over the hills and over the town and back again, and I saw how a man can be master of a craft, and how a craft can be master of an element. I saw the alchemy of perspective reduce my world, and all my other life, to grains in a cup. I learned to watch, to put my trust in other hands than mine. And I learned to wander. I learned what every dreaming child needs to know -- that no horizon is so far that you cannot get above it or beyond it." Beryl Markham, West With the Night

But let's get back to Gladys Stokes.

She transferred from the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps to the newly formed Women's Royal Air Force in April 1918, where she became a Leading Aircraftswoman. Her story is a remarkable one, with early adventures that are the stuff from which books are written, however, the fact that she was an aircraftswoman – who was responsible for certain aspects of aircraft production in the Great War – fascinated me, and led me to look a little further into the lives of women who took to the air during the 1914-18 war, and in the years that followed. We've all heard of Amelia Earhart and Amy Johnson, but they were simply following in the steps of some truly intrepid flyers – and if you think that women flying combat missions is something new, then think again!

Female pilots volunteering for military service in WW1 included the following brave women: Helene Dutrieu, who made flights from Paris to check on German troop movements. Marie Marvingt flew bombing missions over Germany.

A cadre of Russian aviatrix included Princess Eugenie Shakovskaya, an artillery and reconnaissance pilot, and Princess Sophie Dolgorukaya who was a pilot and an observer. Courageous women, all. Is it any surprise, then, that so many women took to the air in the post-WW1 years?

A cadre of Russian aviatrix included Princess Eugenie Shakovskaya, an artillery and reconnaissance pilot, and Princess Sophie Dolgorukaya who was a pilot and an observer. Courageous women, all. Is it any surprise, then, that so many women took to the air in the post-WW1 years?

I remember listening to recordings of women who had lived through the Great War, and whose lives were changed not only by their experiences, but by the huge shifts in society following the conflict. One woman was asked about being a "flapper" in the 1920's and in reply commented, "They called us flappers because we were like butterflies breaking out of the cocoon and flapping our wings so we could fly." And fly they did, socially, educationally – and quite literally.

While I was in England in October last year, I came across a series of articles in an annual written in the 1930's, and one just fascinated me: Flying As A Career For Girls. Here's how it begins:"For some years now flying has been a delightful hobby for wealthy girls, but at last it is beginning to take its place as providing a career for the not-so-well-off." The article points out that some fledgling female pilots prefer to be taught by their own sex, and commented on the number of flying clubs with "girl instructresses." I think I would have stuck at my flying lessons if I hadn't been instructed aloft by a half-bored pilot with a smoldering cigar that never left his mouth, even as he was shouting commands at me (and that was only my first lesson!).

The records established by women are inspiring even today. The author describes New Zealander Jean Batten as being, "The gamest little airwoman in the world." Batten was often in the news given her flying exploits, especially when she established the record of flying solo from Port Darwin, Australia to Kent, England (8,615 miles in 5 days, 18 hours, 15 minutes).

Other intrepid airwomen include Harriet Quimby, the first women to fly at night, and to pilot her own 'plane across the English Channel (1912).

Other intrepid airwomen include Harriet Quimby, the first women to fly at night, and to pilot her own 'plane across the English Channel (1912).

Alys McKey Bryant, the first woman pilot in Canada (1913)

Alys McKey Bryant, the first woman pilot in Canada (1913)

And one I really love – Bessie Coleman, the first African American, man or woman, to earn a pilot's license.

And one I really love – Bessie Coleman, the first African American, man or woman, to earn a pilot's license.

There's a list that goes on and on of women's accomplishments in the field of aviation in the first 40 years of the last century. Author Dorothy Carter, herself a pilot, wrote many stories for girls and young women, generally featuring an intrepid aviatrix who could not only teach others to fly, but who could teach the men a thing or two about aircraft. I love glancing through these old stories, and reading the biographies of women who took to the skies, especially that extraordinary generation of women between the wars who seemed to be game for almost anything. And I wonder how girls and young women today could be inspired by their stories – they may not want to take to the air, but every woman, in her own way, wants to fly.

There's a list that goes on and on of women's accomplishments in the field of aviation in the first 40 years of the last century. Author Dorothy Carter, herself a pilot, wrote many stories for girls and young women, generally featuring an intrepid aviatrix who could not only teach others to fly, but who could teach the men a thing or two about aircraft. I love glancing through these old stories, and reading the biographies of women who took to the skies, especially that extraordinary generation of women between the wars who seemed to be game for almost anything. And I wonder how girls and young women today could be inspired by their stories – they may not want to take to the air, but every woman, in her own way, wants to fly.

"We swung over the hills and over the town and back again, and I saw how a man can be master of a craft, and how a craft can be master of an element. I saw the alchemy of perspective reduce my world, and all my other life, to grains in a cup. I learned to watch, to put my trust in other hands than mine. And I learned to wander. I learned what every dreaming child needs to know -- that no horizon is so far that you cannot get above it or beyond it." Beryl Markham, West With the Night

Published on January 19, 2012 17:35

January 6, 2012

Downton Abbey - It's Baaaack!

I know so many of you can't wait for the arrival of Downton Abbey's second series to hit the screens in the USA this weekend. I'm afraid I couldn't wait, so I ordered the UK DVD set and was able to watch the whole series over a three-day period some weeks ago (one of my best investments – a code-free DVD player!). Not only am I rather hooked on the series, but this time – as you know – I was particularly interested in how the Great War would be depicted on the home front, especially given the wires that seem to ensnare this particular cast of characters, whether upstairs or below stairs.

I'm not going to give any spoilers here, that would be so unfair, however, I'll just say I was interested to see how the women were portrayed in this series, especially given my interest in women's lives during the 1914-18 war, and how those changes impacted their futures in the following decades. It seemed that each of the Crawley sisters represented the different ways in which women became more independent, how they experienced having a voice and a choice, and then exercised that new freedom. In them we see both the joys of discovery and the disappointments that can accompany taking a road never before traveled. See what you think when the series airs, and in the meantime, I'll be coming back, posting on this blog about the lives of women during that era.

The naysayers were out in force when the second series of Downton Abbey aired in the UK. There were criticisms regarding language (for example, the fact that someone's young man was referred to as her "boyfriend" – which was not used in those days), and comments about costumes and whether so-and-so really would have worn tweeds, or whatever. While I like to see authenticity, we have to remember that this is a story, and in a story sometimes to keep the viewer engaged, one has to sacrifice fact to get to the truth. And I don't think the overall truth of the time period was compromised – the series focuses on a family in the upper echelons of society, with only brief glimpses of those on the ladder's lower rungs. The impact of war is a bit rosier than it might have been, but you get a sense of how some aspects of life will never go back to the way it was before, no matter how much the Dowager might want the pre-war status quo established again.

I still think, though, one of the most poignant moments is when the young Lady Sybil says, "Sometimes it feels as if all the men I ever danced with are dead." And that's what interests me and brings me back to this period in history time and again: 750,000 young men killed in Britain alone, 1,350,000 severely wounded, and – according to the latest estimates – over 200,000 profoundly shell-shocked. And after the war, two million women of marriageable age for whom there was little chance of finding a partner to share life and have a family, were considered "surplus." Now I'm looking forward to Series 3 – I want to know what happens to those Crawley girls. And of course there's – uh-oh, better not say any more ...

Enjoy your visit to Downton Abbey this weekend. I'm expecting the DVD of the "Christmas Special" which aired on December 25th in Britain to arrive any day now. Waiting was never my strong suit!

Next week: Those Magnificent Women & Their Flying Machines.

Published on January 06, 2012 12:12

December 20, 2011

A Very Special Brave Lady

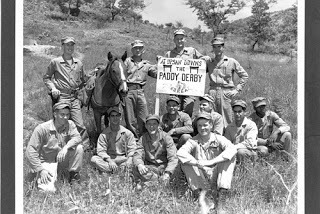

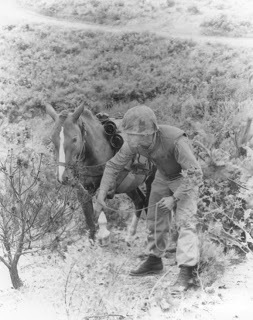

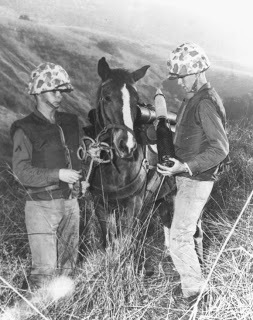

When I sent an email to my friends about my new blog, one of the women I ride with replied with this message: "If you're writing about women who've been to war, you'd better include this brave lady." So I clicked on the link she'd added, and was soon engrossed in the life of a gal I knew nothing about, a Marine Staff Sergeant whose courage in battle has slipped from the story of America in the 20th century, even though the lady in question was featured in Life magazine's, "Celebrating Our Heroes," edition. Listed alongside Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, & Martin Luther King is a small Mongolian mare named Reckless, who became the greatest war heroine horse in American history. She was a lovely lady who won the hearts of her fellow marines with her courage and quirky ways. Here's her story ….

Reckless was recruited into the Marine Corps in October of 1952 by Lieutenant Eric Pedersen. Pedersen was the commanding officer of the Recoilless Rifle Platoon, Antitank Company, Fifth Marine Regiment. Given the long distance endured by ammunition carriers as they took their precious cargo to the front lines, and the threat of enemy engagement along the way, Lt. Pedersen recognized the value of having a horse to help transport ammunition for his platoon's recoilless rifles. After receiving permission from regimental commander, Colonel Eustace P. Smoak, Pedersen and two other Marines set off for the Seoul racetrack. It was there that Pedersen first laid his eyes on the little red racehorse who would later distinguish herself in battle and become a decorated combat veteran. The Marine lieutenant bought her for $250 - and it was his own money.

During the first few nights with the Marines, Reckless, as they named her, was tied in her bunker. This didn't last long because she was soon given free rein to roam around. She visited the Marines in their tents and even spent some restless nights with them. They would just move their sleeping bags to one side and make room for their new recruit. On very cold nights, Sgt Latham, her designated carer/trainer would invite her into his tent to sleep standing up next to the stove. Sometimes she'd even lie down and stretch out. Her early days with the Marine Corps were filled with Sgt Latham putting his new recruit through training. He taught her how to get in and out of a jeep trailer - Reckless had to be quite nimble since the trailer was only 36in by 72in. "She'd jump in the trailer and go in catty-cornered, and I'd tie her down," recalled the Marine.

Latham taught Reckless how to take cover while on the front lines. When tapped on the front leg, she would lay down. The training proved invaluable on many occasions when Reckless was making journey after journey on her own. Latham trained the mare to go straight to a bunker when incoming rounds hit behind the lines. "We'd get incoming there too, and they'd [the enemy] lay it on you. If Reckless was in the back, she'd go to a bunker. All I had to do was yell, "Incoming, incoming!' and she'd go." During training, Latham offered Reckless her first Coke. She liked the fizzy drink so much, she nudged Latham and asked for more. He consulted naval hospital corpsman George Mitchell, who advised she not be given more than a couple of bottles a day – though he wasn't a veterinarian, "Doc" Mitchell became the go-to guy when issues of Reckless' health came up.

There's are a few YouTube clips that tell the tale of Reckless. I was amazed at the pluck and intelligence of this little lady, who would be sent on her way to the front line, often alone with her load of ammunition. She never failed to find her guys, and always came home to her base. Here's what Life magazine had to say about Reckless:During the Battle for Outpost Vegas in March 1953, on one day alone, Reckless made 51 trips from the Ammunition Supply Point to the firing sites, most of the time on her own. She carried 386 rounds of ammo on her back (over 9,000 lbs) and walked over 35 miles through open rice paddies and up steep mountains with enemy fire coming in at the rate of 500 rounds per minute. Wounded twice, she never stopped. She shielded Marines going up to the line, and helped carry the wounded to safety. They'd take the wounded off her back, load her up with ammunition, and send her on her way up to the guns. There's no telling how many lives she helped save.

Reckless was brought home to the United States after the Korean War, and first stepped onto American soil on November 10th 1954. There are wonderful stories of her homecoming, including her presence as an honored guest at parties and receptions (one on the 10th floor of the Marines Memorial Club in San Francisco). It was at Camp Pendleton, where she spent the rest of her days, that she was promoted to Staff Sergeant, with a march-past of 1700 marines – and her sons, Fearless and Dauntless in attendance.

The sorrel mare was retired on Nov. 10, 1960, with full military honors. An article in the San Diego Union stated that General David M. Shoup, then-Commandant of the Marine Corps, had issued this order: "SSgt Reckless will be provided quarters and messing at the Camp Pendleton Stables in lieu of retired pay." Reckless' decorations included two Purple Hearts, Good Conduct Medal, Presidential Unit Citation with star, National Defense Service Medal, Korean Service Medal, United Nations Service Medal, and Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, all of which she wore on her scarlet and gold blanket – and if I know horses, she would have understood exactly how impressive she looked in that blanket.On May 13, 1968, the Marine Corps lost a dear friend when Reckless was injured and had to be put to sleep. Reports put her age at 19 or 20 when she was laid to rest.Surprisingly, there is no official memorial in Washington DC to SSgt Reckless, who could teach some of us a lesson or two about bravery. I say "surprisingly" because I had assumed that the Life magazine citation would have brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars – but that didn't happen. I know there's the argument that money would be better spent on our returning heroes, and that's fair comment – but there's something about the selfless contribution of animals in a time of war that touches hearts and brings attention to the fact that the suffering caused by conflict is as deep as it is broad. On Christmas Day, Steven Spielberg's epic movie, The War Horse opens. I will be one of the first in line to watch the movie as soon as the theater doors are drawn back. As a horse lover I have always been moved by the role played by horses in a time of war – I've read Michael Morpugo's book that inspired both the stage play and Spielberg's movie – and I know I will be in tears before the opening credits are up (I cried buckets when I saw the stage play in London). In the Great War, Britain lost hundreds of thousands of horses; one report suggests some 500,000 went into battle and to their deaths. The War Horse will draw attention – I hope – to the role of animals in wartime. And I hope very much that someone, somewhere – perhaps a TV celebrity known for an affinity with horses, or a movie star, or a much-read journalist – will give a mention to Reckless. It's about time the long hoped-for memorial to Reckless was built in Washington DC. America's true war horse deserves nothing less.For more information on SSgt. Reckless, go to: http://www.sgtreckless.com/Reckless/Welcome.htmlTo see her on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIo3Zf... this post I have sourced information from various places, and in particular an article about Reckless written by Nancy Lee White Hoffman in 1992: http://www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck/sgt-reckless-combat-veteranAnd if I knew how to embed those links, life would be made easier for you – apologies for my non-technical approach to imparting online information links.Finally, here's wishing you Happy Holidays, and many blessings in the year to come.

Next post: Can't resist it – more on Downton Abbey, and those women of the Great War.

Published on December 20, 2011 21:43

December 14, 2011

Another Heroine

Readers who aren't familiar with the British school system may imagine that it's only at Hogwarts where you are assigned a "house," a team to belong to for the rest of your days at the school. But no, it's a hallmark of one's early education "over there" – or it was when I was at school. If you attend a boarding school, your house might literally be the place where you live when not in classes. For those of us who attended regular non-boarding schools, it's a place of belonging, the team you'll be part of for sports, for administration, indeed, for many events in school life. In primary school I was in the "Blue" team, which was all very nice because I liked blue. When I went on to the local girls secondary school at age eleven, I discovered I would be joining Jane Austen house, which turned out to be quite fitting for a would-be writer – and our house color was blue, which was comforting. Being a girls' school, the four teams bore the names of women who might inspire in us the qualities of confidence, commitment to one's work and to society; of bravery and of accomplishment. The other houses were named after Elizabeth Fry (red), who was a Quaker, philanthropist and above all a social reformer with a particular interest in prisons; Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (yellow), a physician and feminist who was the first woman to gain a medical qualification in England, and Edith Cavell (green), a nurse and – effectively – a spy, who was shot by firing squad in Belgium in 1915.

My interest in the history of women in the Great War and the years that followed has given me a great admiration for Edith Cavell, because I don't think I could ever show half the courage she demonstrated on behalf of the Belgian people, and the soldiers she helped to escape across the border to The Netherlands. If you've never come across Edith Cavell's name before and this has piqued your interest, a new book about her by Diana Souhami is a must-read. It's not a fusty old biography of a long-dead spinster, but instead at times reads like a thriller, with so much detail of Edith Cavell's "undercover" work that you are almost on the edge of your seat, hoping that she won't get caught – but of course, she was caught.Edith Cavell had a normal but austere childhood in Norfolk, England. She was the daughter of a vicar, and because of her family's station – the country vicar has a certain status, but generally no money (Jane Austen would have loved Edith Cavell, I think) – Edith became a governess, spending time overseas as well as in England. After a few years the young woman wanted to do more meaningful, so she applied to The London Hospital in Whitechapel, and was accepted to train as a nurse. Edith wasn't the most successful student nurse, and was often reprimanded for various infractions of behavior. Souhami has looked a little deeper into the genesis of complaints against Nurse Cavell, and draws attention to the fact that often these episodes were due to her commitment to her work – for example, she received punishment for being tardy, however, it transpires that she was often late to the dining hall because she was so busy attending to her patients; she would remain with them rather than run off to eat. Poor Edith was often misunderstood.

My interest in the history of women in the Great War and the years that followed has given me a great admiration for Edith Cavell, because I don't think I could ever show half the courage she demonstrated on behalf of the Belgian people, and the soldiers she helped to escape across the border to The Netherlands. If you've never come across Edith Cavell's name before and this has piqued your interest, a new book about her by Diana Souhami is a must-read. It's not a fusty old biography of a long-dead spinster, but instead at times reads like a thriller, with so much detail of Edith Cavell's "undercover" work that you are almost on the edge of your seat, hoping that she won't get caught – but of course, she was caught.Edith Cavell had a normal but austere childhood in Norfolk, England. She was the daughter of a vicar, and because of her family's station – the country vicar has a certain status, but generally no money (Jane Austen would have loved Edith Cavell, I think) – Edith became a governess, spending time overseas as well as in England. After a few years the young woman wanted to do more meaningful, so she applied to The London Hospital in Whitechapel, and was accepted to train as a nurse. Edith wasn't the most successful student nurse, and was often reprimanded for various infractions of behavior. Souhami has looked a little deeper into the genesis of complaints against Nurse Cavell, and draws attention to the fact that often these episodes were due to her commitment to her work – for example, she received punishment for being tardy, however, it transpires that she was often late to the dining hall because she was so busy attending to her patients; she would remain with them rather than run off to eat. Poor Edith was often misunderstood.

Eventually, after qualifying, and then assuming several nursing positions of increasing responsibility, Edith Cavell was offered a position in Brussels, her remit being to bring greater professionalism to the role in Belgium, and to found a school of nursing. When war broke out in 1914, Edith and her nurses provided food, clothing and medical care for many refugees fleeing the German army. Soon, however, her work became more serious when she became involved in harboring escaping French and British soldiers who had been wounded and separated from their regiments, providing a vital link in resistance to the German occupation. Souhami's book brings the time alive, as she describes the antics of some of the young soldiers. Those who were fit enough had to leave the hospital during the day; they were instructed to lay low and return each night for a bed and a meal until it was their time to be taken by a guide across the border. But many of those young men wanted to party - most were barely out of their teens – and could often be heard making their way back to Cavell's hospital, singing at the tops of their voices – usually a British marching song, such as "Tipperary" – or laughing and joking in their native language.

Nurse Cavell would often lead the young soldiers to meet the resistance guide, walking ahead of a man in the dawn hours, her beloved dog, Jack, at her side. I think I would have been on the first boat home, or at least across that border myself. Perhaps that's why the stories of women and men who have lived secret lives so that they might help others has always fascinated me. Certainly there were those who thrived on the adrenalin rush, but at the end of the day, it was a very real game of roulette and took immense courage. Every time Cavell answered the door and took a young soldier into her care, she was spinning the wheel, taking a gamble with her own life. Finally, one day, the wheel stopped turning.Thirty-three men and women from the resistance network of which Cavell was a crucial part, were rounded up in the sweep that eventually led to her death. Letters were sent from the British Foreign Secretary, asking for Cavell to be released from prison, from the Spanish Ambassador and from the American Ambassador in London. Others petitioned for clemency on Cavell's behalf. Nurse Cavell had spent two months alone in her cell before her trial in October 1915. German prosecutors worked hard to send Cavell to the firing squad, and again there were last-minute attempts to save her life, but she received the most severe sentence. Following news of her death, Britain was gripped by a surge in enlistment. I often wonder what Nurse Cavell would have thought of about that.

Her body, hurriedly buried following her execution, was exhumed and returned to Britain in 1919, and in the way that stories come full circle, so must this story of my admiration for Nurse Cavell.

As some of you may know, I was in England in October, for my Dad's 85th birthday. As a special treat, I took my parents to a special "Sherlock Holmes Mystery Dinner" aboard the steam-hauled Pullman service run by the volunteers of the Kent & East Sussex Railway. With Remembrance Day just over a week away, everyone was wearing a poppy, either in a buttonhole or pinned to a dress – it's very much the "Lest We Forget" tradition in Britain. That sentiment came ever closer when the train stopped at the old station in Newenden, East Sussex, where the "Cavell Van" rests. In Britain, a train's freight cars were traditionally known as "goods vans." This van had not only carried Edith Cavell's casket into London, but also the body of the Unknown Warrior, who was to be buried at Westminster Abbey and would ever more bring to mind those "missing" in the war.

On this cold October evening, an empty casket with a wreath of white chrysanthemums represented the heroine who had risked her life to aid others. It was so still inside the van when I walked in and said a silent prayer for Nurse Cavell. At school I wasn't a member of the house that bore her name, but I kept the story of her life close to heart.

"Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone." Edith Cavell

Published on December 14, 2011 18:05

November 30, 2011

On Kindness ....

An article appeared in the 1915 edition of Woman's Magazine, on the subject of "Making Children Kind." The article drew my attention, not least because I had been discussing the issue of kindness with some friends recently, and I found it interesting that almost 100 years ago the subject of teaching children kindness was of great importance. Mind you, if we put it in context, by the middle of 1915 Britain was already experiencing a dramatic loss of life in the Spring Offensive – an early battle in the 1914-18 war, which was already casting a pall not only across Europe, but the Empire. Perhaps that's why kindness and the issue of how people treated each others became a topic of focus in a range of articles written at the time. It begs a couple of questions: Might the war not have happened if a whole host of individuals had been a bit kinder? Do kind people brandish guns and kill others? But here's how that article opened:

"He who plants a virtue in the mind of a little child makes an investment which may yield a rich interest of material and moral blessings. We can make no graver mistake than to develop the intellect at the expense of the heart."

I've given much thought to that opening, not just with regard to kindness and children, but kindness between adults. Are we all naturally kind? Or is kindness something we should recognize in ourselves when we see it, and then try enhance the trait? Could we ask the question, "What would kindness do?" more often, or even, "How would it be, if I were more kind?" Maybe such self-reflection might lead to a more peaceful life, and certainly research has shown that kindness is good for you.

I think we all know unkindness when we're on the receiving end of it, or if we observe it inflicted upon another – but brave is the person who takes a stand. Let me recount a story that comes to mind: A couple of years ago, while shopping at a local grocery store, a friend of mine watched the following scene unfold at the deli counter. Now, this market just happens to be right next to the local college, and is also known for great sandwiches and to-die-for fresh breads – so it's a hit with the students. A middle-aged woman was serving, scurrying from customer to customer with smile on her face as she endeavored to fill orders as quickly as possible during the lunchtime rush. A girl of about 16 was waiting with her mother, and as the parent stood to one side, the girl placed her order, specifying that she wanted a fresh baked roll. The server explained that there would be a wait of just a few minutes as a fresh batch of bread rolls was due out of the oven shortly. Well, this wasn't good enough for Miss Sweet Sixteen, who proceeded to rant at the poor woman, criticizing her inability to serve customers and pointing out other perceived shortcomings. The server's eyes filled with tears, yet the girl went on. My friend turned to the mother and asked if the girl was her daughter, to which the woman replied (smiling), "Yes, she is." My friend looked at the woman, shook her head and said in a manner that could not be construed as complimentary, "You must be so very proud." Then she left the store, disgusted. She said to me later, "Jackie, if I had done that, my mother would have had me by the scruff of my neck, marched me out of the store, and I would have been grounded for the rest of my life!"

The fact is that, yes, the girl who lost her temper was rude and ill-mannered, but she was also unkind, to the point of being cruel – and isn't cruelty another level of unkindness?

The writer of the 1915 article points to the supervised responsibility for animals and inculcating a regard for wildlife as being building blocks in developing the kindness trait in children, and points to the link between a lack of kindness and cruelty. Here's what the writer said – which in more modern language we're reading in so many articles published today: "…. psychologists showed us that there is an intimate relation between cruelty and other evil passions of mankind. Therefore, since cruelty is a most powerful element of evil, the lessening of cruelty will greatly increase the happiness of the human race."

While the article points to teaching children to consider animals as friends, looking upon them with interest and respect, other philosophies have spoken to the interconnectedness of life; that when we injure another, we injure ourselves, and that we are increased by seeing ourselves even in those we might not naturally consider kin.

Since reading that article, I am reminded of how important it is to be kind, and kindness is so allied to respect. Years ago, when the majority of people lived in much closer communities, kindness was a glue that held people together, a trait that was all-important because you saw the same people almost every day – at work, the store, the school. Now we're more scattered, and I sometimes think our connections are scattered too.

The article ends with the writer predicting that in teaching children kindness, "Love and Justice – moral faculties which make (the child) a desirable citizen and friend of the race – are aroused, strengthened and developed by early teachings …." And I would have added, "And by example."

I'll end with that well-known bumper-sticker aphorism:

So, what do you think? How do we teach kindness? How do we lead by example? And if you like, give a shout-out to the kindest person you know, and tell us why – we could all use those stories of kindness. And I'll start the ball rolling here. An act of kindness that touched me deeply was when the children of a neighbor came to my door with an old jam-jar filled with flowers on the day my old dog passed away. The three stood there, blushing with tears as the oldest stepped forward, handed me the flowers and said, "We're really sad about Sally." It was a kindness that was balm for my aching soul.

Next week: An ordinary woman who became extraordinary.

Published on November 30, 2011 17:20

November 15, 2011

What The Dickens?

I know writers are not supposed to admit something like this, but I confess, I have never been a fan of Charles Dickens. Certainly I thought A Christmas Carol was a lot of fun, with ghosts clanking about and showing us what Christmas spirit was all about, and without doubt, he was as much a social commentator as a novelist, but there it ends for me. One of my friends would read a novel by Dickens every summer, which as far as I was concerned, really would have made the best of times become the worst of times (that line courtesy of A Tale of Two Cities?).

Cast adrift from my schooldays, I thought that might be the end of any relationship between myself and Dickens, apart from watching the odd remake of Great Expectations on either the silver or small screen. Then a few years ago, while looking up horse-related quotes, I came across the following, written by Monica Dickens: "Riding is a complicated joy. You learn something each time. It is never quite the same, and you never know it all."

(Any excuse to add a Thelwell cartoon ....)

I loved those words from Monica Dickens immediately, not only because I love horses, and know intimately the experiences that inspire such a sentiment, but I thought it could also be applied to the process of writing, which led me to consider the many ways in which my two passions often run parallel – the writing and the riding. And I became interested in Ms. Dickens, great- grand daughter of Charles Dickens.

As you know – because it's the foundation of this blog – I do a fair amount of background reading and research to give color and depth to my series featuring Maisie Dobbs, and part of that is in reading fiction written in the middle years of the last century, from the 1920's to the 1940's. I do that to increase my awareness of language, of the way people spoke during the era – their vocabulary and rhythm of speech – and also to give some depth to my understanding of the mores of the time. Reading Monica Dickens has not only added to that understanding, but given me a fresh appreciation of a writer I knew just a little about – I had recognized her name because she wrote a column for a magazine my mother read when I was a child.

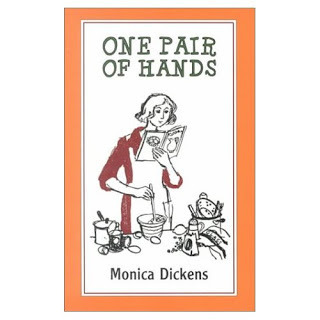

With sharp skills of social observation and a wit as spiky as that of Jane Austen, Monica Dickens' work is now coming to the attention of a new generation of readers. Reprints of her novels and non-fiction are appearing, and I especially love the editions from Persephone Classics. I started delving into M. Dickens work again with her autobiographical One Pair of Hands, which is at once a comedy of errors and an incisive yet humorous insight into the lives of the more privileged between the wars.

With sharp skills of social observation and a wit as spiky as that of Jane Austen, Monica Dickens' work is now coming to the attention of a new generation of readers. Reprints of her novels and non-fiction are appearing, and I especially love the editions from Persephone Classics. I started delving into M. Dickens work again with her autobiographical One Pair of Hands, which is at once a comedy of errors and an incisive yet humorous insight into the lives of the more privileged between the wars.

Monica Dickens was born to an upper class London family in 1915, and known as "Monty" to family and friends. She was expelled from the exclusive St. Paul's Girls' School, then later presented at court as a debutante. However, she threw all caution to the wind when she decided to broaden her worldview by becoming a servant, a "below stairs" employee – much to the mirth of her family, who by all accounts were used to her eccentricities. Those experiences became the foundation for One Pair of Hands. How she got away with it and managed to gain references for job after job is beyond me, with failed suppers, kitchen breakages replaced out of her own pocket, employers that ranged from shifty to accommodating, and the farcical open and closed door shenanigans she had to go though when she realized that the guest list for a country "Friday to Monday" at the house where she was working as a cook, included an old flame. One Pair of Hands is a wonderful, short read, but one that gives you the measure of Miss Dickens. She later became a nurse, and also worked in an aircraft factory – indeed her exploits mark her as something of a second generation Bright Young Thing, someone daring, but in a very down to earth way – and that's certainly expressed in her writing.

Having devoured One Pair of Hands, I wanted to read more of this palatable Dickens, so bought a copy of Mariana, a coming of age story that takes Mary, the heroine of the tale, from childhood to young married life, through the 1930's to second world war, when she awaits news of her naval officer young husband, who she fears might have lost his life when his ship was torpedoed. If you've read I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, this book is of the same ilk – but I enjoyed it much more. Dickens manages to make the often unlikeable Mary a character both strong and sympathetic at the same time – and gives an incredible insight into the lives of her characters at a time known for the changes wrought upon society.

And to end this week's post, here's just one more Monica Dickens quote:

"Writing is a cop-out. An excuse to live perpetually in fantasy land, where you can create, direct and watch the products of your own head. Very selfish."

Uh-oh ... what do you think about that? I can see her point, but I'm not sure that I agree it's selfish any more than indulging any other passion (tinkering with cars, riding horses, gardening, playing golf). I feel very blessed to be a teller of stories, though sometimes that fantasy land is a very troubling place to be.

Next time: On Kindness ….

Published on November 15, 2011 07:28

October 24, 2011

Adventure & Service

I've always been captivated by acts of derring-do, by the exploits of adventurous men and women. Especially women who blazed a trail (I know, I use that term a lot) in lands that were supposedly inhospitable to the fairer sex. From Isabella Bird, to the likes of Gertrude Bell, Amelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and Beryl Markham (I listened to the audio version of West With The Night and was torn between trying to make the story last and consuming the whole thing without a break). There are adventurers who have caused me to question their sanity. While reading Into Thin Air, the story of disaster on Mt. Everest, I was left wondering if the mountaineers who risked their lives in freezing – really freezing – conditions were not all a bit unhinged or, indeed, stark raving bonkers. However, as the orthopedic surgeon said to me a day before he operated on my crushed shoulder and badly broken arm (which looked like a very long eggplant at the time), after I'd asked him if I would ever ride again, "We all live with our own level of risk, Jackie." He also said that no one in his family was allowed to have anything to do with horses or motorbikes. Let that be a warning to you.

When war broke out in 1914, many of those young men and women who enlisted for service could think no further than the adventure it might offer – the same thing happens even today. They say that wars are fought by the young because they haven't a sense of their own mortality. Enlistment numbers dropped dramatically following the Spring Offensive 1915, when the daily lists of the dead and missing were published, and were growing longer by the day – it had suddenly hit home that going to war could lead you to lose your life.

Many of those who initially rushed to sign up had never been further than the boundary of their village, or town, and had known few people outside their neighbors and, later, those they worked with. Going to war was to be the big adventure. Which brings me to two women who immediately saw the opportunity to blend adventure with service: Elsie Knocker and Maire Chisholm, who, arguably, became the most famous women of the Great War, as news of their courage reached Britain and, indeed, the rest of the world. Here's a potted version of their story:At the outset of war, Elsie, 30, a trained nurse, was divorced and the single mother of a young son, and Maire, 18, hailed from Scotland. It was their love of motorbikes that brought them together, when they met at a motorcycle club in Bournemouth in southern England, where they raced in rallies between 1912 and 1914. Within a month of war breaking out in August 1914, they had roared off to London on their motorbikes to "do their bit." Initially they volunteered for the Women's Emergency Corps, where they became dispatch riders – causing something of a scandal with their masculine breeches, leather jackets and boots. That didn't last long, because just a month later they were in Belgium driving ambulances, taking wounded soldiers from the front lines to the distant military hospitals – while at the same time dodging sniper fire and bombardment while retrieving the grievously wounded from the battlefield. They worked all hours at the hospital treating burns, dysentery, gas-gangrene and shell-shock.

They realized that many of the soldiers were dying of their wounds due to the long journey, so they set up a medical post close more or less on the front line. Aided by Lady Dorothy Fielding, daughter of the Earl of Denbigh, and a young American nurse, Helen Gleason, they fought to save men – and they fought the British Military Establishment, who were determined to "put these women in their place" and shut down the post. Two men helped them stay to do the work they knew was essential to saving lives: Arthur Gleason, Helen's husband, who discovered the shocking extent of the British and French casualties, and Baron Harold de T'Serclaes, who had fallen in love with Elsie.

But just consider their conditions: Their working area was a cellar under a ruined house, with ceilings less than six feet high – this is where they lived, worked, cooked meals and tended to the wounded. They rose at dawn each day and made up hot drinks in buckets, which they took to soldiers on the front line, walking through waist-high mud on the way. They slept on straw, and such was the level of contamination due to the shelling and death, that water had to be shipped from England and then boiled. When the fighting was a at it's most fierce, they slept in their clothes and could not even bathe for weeks. It was reported that at one point Mairi had to be cut from her undergarments after first soaking them, so that her skin would not be removed at the same time. And this was their life, in the town of Pervyse, for three and a half years.

[image error]

Elsie and Mairi became known as the "Angels of Pervyse" as news of their work spread overseas. Apparently, one London newspaper trumpeted their work with the headline, "Sandbags Instead of Handbags!" The King of Belgium awarded them medals that entitled them to be saluted by all soldiers.The two women had to return to the UK when they were almost killed in the shelling, and were poisoned in an arsenic gas attack.You would have thought that there would be a statue somewhere in Britain to honor Elsie Knocker and Mairi Chisholm, wouldn't you? But there isn't, sadly. However, a couple of years ago these daring, brave women received some of the recognition they deserved, albeit long after they died, when Dr. Diane Atkinson published her book, "Elsie and Mairi Go To War: Two Extraordinary Women on the Western Front."

I'm not sure this is the adventure I would have chosen, but it's an inspiring story. Adventure combined with service is a compelling proposition.Who are your favorite adventurers? Who has inspired you with their exploits – and acts of derring-do – far from home? And what would be your dream adventure, if you had the opportunity to make it happen? I have a spare copy of Diane Atkinson's book about Elsie & Mairi to send to the writer of a comment left in response to one or all of those questions (the winner be chosen at random by an independent observer, probably my Mum as I'm flying to the UK this week and she'll have a chance to look at the blog). If you leave a comment, please make sure I have a way of getting in touch with you – you can email me at jacquelinewinspear@gmail.com.There's also a novel that tells of their exploits in a story, however, I have not read that book, but thought you might like to know about it: Angels in Flanders by Jean-Pierre Isbouts.

Next time: Another – and much funnier – Dickens.

When war broke out in 1914, many of those young men and women who enlisted for service could think no further than the adventure it might offer – the same thing happens even today. They say that wars are fought by the young because they haven't a sense of their own mortality. Enlistment numbers dropped dramatically following the Spring Offensive 1915, when the daily lists of the dead and missing were published, and were growing longer by the day – it had suddenly hit home that going to war could lead you to lose your life.

Many of those who initially rushed to sign up had never been further than the boundary of their village, or town, and had known few people outside their neighbors and, later, those they worked with. Going to war was to be the big adventure. Which brings me to two women who immediately saw the opportunity to blend adventure with service: Elsie Knocker and Maire Chisholm, who, arguably, became the most famous women of the Great War, as news of their courage reached Britain and, indeed, the rest of the world. Here's a potted version of their story:At the outset of war, Elsie, 30, a trained nurse, was divorced and the single mother of a young son, and Maire, 18, hailed from Scotland. It was their love of motorbikes that brought them together, when they met at a motorcycle club in Bournemouth in southern England, where they raced in rallies between 1912 and 1914. Within a month of war breaking out in August 1914, they had roared off to London on their motorbikes to "do their bit." Initially they volunteered for the Women's Emergency Corps, where they became dispatch riders – causing something of a scandal with their masculine breeches, leather jackets and boots. That didn't last long, because just a month later they were in Belgium driving ambulances, taking wounded soldiers from the front lines to the distant military hospitals – while at the same time dodging sniper fire and bombardment while retrieving the grievously wounded from the battlefield. They worked all hours at the hospital treating burns, dysentery, gas-gangrene and shell-shock.

They realized that many of the soldiers were dying of their wounds due to the long journey, so they set up a medical post close more or less on the front line. Aided by Lady Dorothy Fielding, daughter of the Earl of Denbigh, and a young American nurse, Helen Gleason, they fought to save men – and they fought the British Military Establishment, who were determined to "put these women in their place" and shut down the post. Two men helped them stay to do the work they knew was essential to saving lives: Arthur Gleason, Helen's husband, who discovered the shocking extent of the British and French casualties, and Baron Harold de T'Serclaes, who had fallen in love with Elsie.