Aurora Levins Morales's Blog

September 12, 2017

Mudslides

I’ve been thinking about mudslides. All along the roads of hurricane-swept Puerto Rico there must be hundreds of places where the orange clay of our mountains has lost its grip on rocks and roots and cascaded across the narrow roadways, taking uprooted trees with it and blocking traffic. In spite of power outages and flood damaged homes, Puerto Rico got off easy compared to our neighbors. Except that the physical derrumbes have come on top of a landslide of massive Wall Street orchestrated robberies that have gutted our infrastructure, our public health system, our entire economy, so we were already up to our necks in mud. And if it were only chance that sent Irma careening through the Caribbean, tearing off roofs and coffee blossoms, and ripping the social fabric to shreds, that would be one thing. But it wasn’t. Last month, three days after terrorist attacks in Barcelona left 16 dead, an entire mountainside came down on the people of Regent, on the outskirts of Freetown in Sierra Leone and killed at least 500 people. As is painfully usual, world governments and the corporate media exclaimed over the first event and pretty much ignored the second.

I’ve been thinking about mudslides. All along the roads of hurricane-swept Puerto Rico there must be hundreds of places where the orange clay of our mountains has lost its grip on rocks and roots and cascaded across the narrow roadways, taking uprooted trees with it and blocking traffic. In spite of power outages and flood damaged homes, Puerto Rico got off easy compared to our neighbors. Except that the physical derrumbes have come on top of a landslide of massive Wall Street orchestrated robberies that have gutted our infrastructure, our public health system, our entire economy, so we were already up to our necks in mud. And if it were only chance that sent Irma careening through the Caribbean, tearing off roofs and coffee blossoms, and ripping the social fabric to shreds, that would be one thing. But it wasn’t. Last month, three days after terrorist attacks in Barcelona left 16 dead, an entire mountainside came down on the people of Regent, on the outskirts of Freetown in Sierra Leone and killed at least 500 people. As is painfully usual, world governments and the corporate media exclaimed over the first event and pretty much ignored the second.

Sierra Leone mudslide, August, 2017

Sierra Leone mudslide, August, 2017

This isn’t new. When bombs injured and killed civilians in Paris and Beirut in the same week, when two communities of people going about their own business were ripped apart by the same hands, we were told all kinds of details about those who died in Paris, the neighborhoods where they lived, what everyone was doing when it happened--but there were no interviews with vendors in the open-air market that was bombed in Beirut, and the news stories kept describing their neighborhood as a “stronghold,” constantly underlining the message that the Beiruti people who died while shopping for their dinners were not as innocent as the Parisians who died in concert halls, stadiums, or bakeries.

This isn’t new. When bombs injured and killed civilians in Paris and Beirut in the same week, when two communities of people going about their own business were ripped apart by the same hands, we were told all kinds of details about those who died in Paris, the neighborhoods where they lived, what everyone was doing when it happened--but there were no interviews with vendors in the open-air market that was bombed in Beirut, and the news stories kept describing their neighborhood as a “stronghold,” constantly underlining the message that the Beiruti people who died while shopping for their dinners were not as innocent as the Parisians who died in concert halls, stadiums, or bakeries.So, the fact that US and European heads of state didn’t rush to make statements about the Sierra Leone mudslide, that offers of aid were late, reluctant and insultingly small, that no buildings were lit up in the colors of the Sierra Leone flag, that there were no moments of silence, no Facebook filters or safety check-ins for friends and relatives in Freetown, no “we are all Sierra Leone” t-shirts, is just one more expression of why it’s necessary to keep saying that Black Lives Matter. Every single day the governments and media outlets of the global north tell us through word and deed that they don’t.

But there’s also another kind of lie at play here. That Barcelona was human violence and Freetown was nature.

Surface flooding in Freetown, Sierra Leone. But there’s also another kind of lie at play here. That Barcelona was human violence and Freetown was nature.

Surface flooding in Freetown, Sierra Leone. But there’s also another kind of lie at play here. That Barcelona was human violence and Freetown was nature.This year Sierra Leone had three times the expected amount of rain. That rain fell on deforested slopes covered with the insecure housing of the very poor, who were squatting there because they had nowhere else to go, and the government did not warn or evacuate them. So yes, the prolonged looting of West African societies, the slave trade, colonialism, neoliberal economics, governments indifferent to their own people and/or ineffective at meeting their needs, the desperation of poverty, landlessness, homelessness—all of these factors placed those people in the path of that mud, and those are human crimes.

What keeps being hidden in plain view is that the rain itself is a crime, or at least the result of one.

Heavier than normal rainfall is one of the documented effects of global climate disruption, which overwhelming scientific evidence shows is being caused by human greed, mostly on the part of the rich countries of the global north. The rain itself is a crime.

Heavier than normal rainfall is one of the documented effects of global climate disruption, which overwhelming scientific evidence shows is being caused by human greed, mostly on the part of the rich countries of the global north. The rain itself is a crime. As temperatures rise, wet places get wetter, dry places get drier, and ordinary rainfall becomes torrential, leading to massive floods and mudslides, many of them in the tropics. And as the oceans warm, hurricanes grow stronger, bigger, more frequent and extreme.

These derrumbes, these unfastenings of the earth from its moorings, these winds that uproot us, these floods that drown our cities and fields, have authors, people with names and addresses who sit in board rooms and government offices and decide to keep plundering the earth for riches and burning fossils to fuel their plundering. This week Donald Trump appointed a climate denier with no scientific background at all to head NASA, which plays a leading role in worldwide climate science, monitoring solar activity, sea level rise, the temperature of the atmosphere and the oceans, the state of the ozone layer, air pollution, and changes in sea ice and land ice. This is a man who demanded that President Obama apologize for funding climate research. They want to hide the evidence of their ecocide.

So, stop calling the events of this summer natural disasters. Stop pretending it’s just hurricane season, just rain, just wind. Stop saying “accident” about the toxic chemicals saturating the water and soil of Houston and the Texas Gulf Coast. Stop thinking it’s luck that Cubans survive the hurricanes that kill their neighbors. It isn’t luck. It’s choice. It’s socialism.

When my Taino ancestors decided to cut down trees to make canoas or houses, they did ceremonies honoring each tree for its gift. They didn’t clear cut mountainsides, leaving the soil unrooted so that it buried whole cities of sleeping people. They told stories about the powerful spirit called Guabancex, who sent hurricanes upon the people when she was angry, whose helper Guataubá brought the winds, while Coatriskiye made the floods. They believed in human reciprocity with the rest of nature, a code of conduct that when broken, had consequences. They were right.

When my Taino ancestors decided to cut down trees to make canoas or houses, they did ceremonies honoring each tree for its gift. They didn’t clear cut mountainsides, leaving the soil unrooted so that it buried whole cities of sleeping people. They told stories about the powerful spirit called Guabancex, who sent hurricanes upon the people when she was angry, whose helper Guataubá brought the winds, while Coatriskiye made the floods. They believed in human reciprocity with the rest of nature, a code of conduct that when broken, had consequences. They were right. Mudslides, floods, droughts, and hurricanes aren’t bad luck.

They’re consequences.

Please visit my Patreon page and join my online community of supporters.

Please visit my Patreon page and join my online community of supporters.

Published on September 12, 2017 12:31

August 16, 2017

Fog

Every day, as the sun reaches the last segment of western sky, the Pacific Ocean sends its moist breath in an airborne tide across the dry hills. All night, the fog pools, a milky aerial sea that settles over pastures, marshes, roadside eucalyptus, and the lines of willows along the estero, so that the first light on this land is always pearl. The presence of so much water in the air brings sounds closer. On the mountain where I was born, Caribbean clouds sank down to nest on the green summits, and you could hear the clank of a bucket on the next mountain as if it were a few feet away. Here, the landscape is a pale gold, and the fog is full of mourning doves and the distant lowing of cattle.

Every day, as the sun reaches the last segment of western sky, the Pacific Ocean sends its moist breath in an airborne tide across the dry hills. All night, the fog pools, a milky aerial sea that settles over pastures, marshes, roadside eucalyptus, and the lines of willows along the estero, so that the first light on this land is always pearl. The presence of so much water in the air brings sounds closer. On the mountain where I was born, Caribbean clouds sank down to nest on the green summits, and you could hear the clank of a bucket on the next mountain as if it were a few feet away. Here, the landscape is a pale gold, and the fog is full of mourning doves and the distant lowing of cattle.

My brother wrote that he came from the biggest body of water on earth, the sky. I came from the rain. I am a child of torrential downpours and I grew like the little ferns, unfurling in the presence of water, or the purple day lilies that spring open to meet each rainfall, revealing cups full of golden pollen. The high place where we slept and woke held seven rain fed springs, manantiales, whose water ran downhill, along the folds of the land, creeks that became streams and then rivers, and finally found their way to the sea. Like the water of those springs, I’ve traveled far from my source. Only rarely am I able to return, to stand on a high ridge with clouds blowing around me, to smell fern and yagrumo, and listen to coquís, the tiny, uniquely Puerto Rican tree frogs whom the Taino believed were lost children, calling for their mothers and summoning rain. But the taste of that water, the taste of wild guavas, the taste of that air, full of lichen stained pomarrosa trunks and the earthy scent of banana leaves, lives under my tongue.

My brother wrote that he came from the biggest body of water on earth, the sky. I came from the rain. I am a child of torrential downpours and I grew like the little ferns, unfurling in the presence of water, or the purple day lilies that spring open to meet each rainfall, revealing cups full of golden pollen. The high place where we slept and woke held seven rain fed springs, manantiales, whose water ran downhill, along the folds of the land, creeks that became streams and then rivers, and finally found their way to the sea. Like the water of those springs, I’ve traveled far from my source. Only rarely am I able to return, to stand on a high ridge with clouds blowing around me, to smell fern and yagrumo, and listen to coquís, the tiny, uniquely Puerto Rican tree frogs whom the Taino believed were lost children, calling for their mothers and summoning rain. But the taste of that water, the taste of wild guavas, the taste of that air, full of lichen stained pomarrosa trunks and the earthy scent of banana leaves, lives under my tongue.  The mornings here smell entirely different, of ripe grass and fruit laden blackberry vines, the mousy dankness of hemlock pollen, and slow estuary water. But just as every molecule of oxygen we breathe has traveled in and out of billions of lungs, linking everything that inhales, the droplets of water suspended over the rich coastal homeland of the Miwok have been around the world, and at least some of them have gathered in the innermost cups of bromeliads, high in the branches of Indiera trees, dripped from wild ginger buds into the red clay of my home, made their way around glistening green serpentine, and filtered down into those springs, only to bubble up and flow away into the one great sea that girdles the earth, and they are hovering here, all around me, brushing my face, and the dry, yellow slopes where black cattle graze. By ten o’ clock the fog will thin and tear into rags of cloud, revealing a sky made blue by reflected ocean. The suspended water will turn to transparent vapor, and turkey vultures will once more trace their slow circles in the sunny air overhead. And I will go on into my day, shaded by the great trees of the cordillera, the taste of those mountain springs trickling through me, staining my words with rainwater in this rainless land.

The mornings here smell entirely different, of ripe grass and fruit laden blackberry vines, the mousy dankness of hemlock pollen, and slow estuary water. But just as every molecule of oxygen we breathe has traveled in and out of billions of lungs, linking everything that inhales, the droplets of water suspended over the rich coastal homeland of the Miwok have been around the world, and at least some of them have gathered in the innermost cups of bromeliads, high in the branches of Indiera trees, dripped from wild ginger buds into the red clay of my home, made their way around glistening green serpentine, and filtered down into those springs, only to bubble up and flow away into the one great sea that girdles the earth, and they are hovering here, all around me, brushing my face, and the dry, yellow slopes where black cattle graze. By ten o’ clock the fog will thin and tear into rags of cloud, revealing a sky made blue by reflected ocean. The suspended water will turn to transparent vapor, and turkey vultures will once more trace their slow circles in the sunny air overhead. And I will go on into my day, shaded by the great trees of the cordillera, the taste of those mountain springs trickling through me, staining my words with rainwater in this rainless land.

Published on August 16, 2017 18:24

July 9, 2017

Guanakán

This piece was written in 2013, was given as a talk at UC Berkeley, and was published in nineteen sixty-eight, the Ethnic Studies journal at UCB. This is an excerpt.

The body is a storyteller. Each act of illness is an epic tale about interactions of flesh, spirit, and environment, for which we have no language, since we have split existence into these three domains. Language, naming, is a way to make the overwhelming sensory flood of experience manageable, and for the sake of defining this against that, we distinguish things, separate them, hold them against each other, make culture and are made by it, and still the truth of our bodies lies in a realm language can’t fully grasp, because to speak truly means surrendering the categories on which we have built our sense of reason and control, categories that are the tools of our daily work, as practical in their uses as scissors and hoe.

The body is a storyteller. Each act of illness is an epic tale about interactions of flesh, spirit, and environment, for which we have no language, since we have split existence into these three domains. Language, naming, is a way to make the overwhelming sensory flood of experience manageable, and for the sake of defining this against that, we distinguish things, separate them, hold them against each other, make culture and are made by it, and still the truth of our bodies lies in a realm language can’t fully grasp, because to speak truly means surrendering the categories on which we have built our sense of reason and control, categories that are the tools of our daily work, as practical in their uses as scissors and hoe.

Consider skin: living in my skin, we say, jumping out of my skin, skin the boundary between us and not us, skin the receptacle of selfhood, skin, the percentages and shades of melanin, used to further shuffle and deal out the human deck, arrange us on a spectrum, dole out more and less of everything based on these degrees of difference in how we reflect light into each other’s eyes. We think skin is like the walls of our houses, that only sharp objects, or very hot ones, can open it, but skin is permeable. It isn’t the barrier between us and the world, it’s a conversation, cells lined up in a smooth collaboration, a layered surface that is constantly exchanging molecules with everything else. What’s more, a surface full of doors and windows, through which all kinds of wildlife passes. If skin is the wall of a house, that house is made of dried grass, is full of insects and small mammals and nesting birds, is its own habitat, constantly shedding stalks, or, to change the metaphor, is made of soft wood, growing mosses and mushrooms on its surface even as the shredded bark and wood fall away into the rich surrounding soil. Like anyone whose life depends on being heard, our bodies tell their stories over and over and louder and louder until they are shouting, spewing symptoms. But wait. There’s that word body again, with its lie of separation. And yet it’s far too bulky to keep saying body-mind-nature-thing. So, I am renaming it here and now. I will call it guanakán which is constructed from Taíno language parts to mean “our center,” that cloudy gathering of denser particles and pulses in which our awareness exists. Our location. From now on, when I say guanakan speaks, when I hand it to you, take it to be a basket in which everything we think of as body and mind and spirit and ecosystem coexist, and often, but not always, are each other. Well, then guanakan must tell its story. It does so without conscious decision. Storytelling is its being. When a hard object, denser than flesh, strikes flesh—a billy club, say—the strands of light and protein we call nerves begin winking and flashing their signal, telling receptors everywhere “something is harming us” which we call pain, and clusters of molecules rush out into the bloodstream, shouting at the legs to run, pulling blood away from its other work, away from gut and face and the many places of daily chores, into the trembling muscles of the thighs, and we call this fear. Coagulants crowd around the broken tissues, making bruises but preventing hemorrhage.

Consider skin: living in my skin, we say, jumping out of my skin, skin the boundary between us and not us, skin the receptacle of selfhood, skin, the percentages and shades of melanin, used to further shuffle and deal out the human deck, arrange us on a spectrum, dole out more and less of everything based on these degrees of difference in how we reflect light into each other’s eyes. We think skin is like the walls of our houses, that only sharp objects, or very hot ones, can open it, but skin is permeable. It isn’t the barrier between us and the world, it’s a conversation, cells lined up in a smooth collaboration, a layered surface that is constantly exchanging molecules with everything else. What’s more, a surface full of doors and windows, through which all kinds of wildlife passes. If skin is the wall of a house, that house is made of dried grass, is full of insects and small mammals and nesting birds, is its own habitat, constantly shedding stalks, or, to change the metaphor, is made of soft wood, growing mosses and mushrooms on its surface even as the shredded bark and wood fall away into the rich surrounding soil. Like anyone whose life depends on being heard, our bodies tell their stories over and over and louder and louder until they are shouting, spewing symptoms. But wait. There’s that word body again, with its lie of separation. And yet it’s far too bulky to keep saying body-mind-nature-thing. So, I am renaming it here and now. I will call it guanakán which is constructed from Taíno language parts to mean “our center,” that cloudy gathering of denser particles and pulses in which our awareness exists. Our location. From now on, when I say guanakan speaks, when I hand it to you, take it to be a basket in which everything we think of as body and mind and spirit and ecosystem coexist, and often, but not always, are each other. Well, then guanakan must tell its story. It does so without conscious decision. Storytelling is its being. When a hard object, denser than flesh, strikes flesh—a billy club, say—the strands of light and protein we call nerves begin winking and flashing their signal, telling receptors everywhere “something is harming us” which we call pain, and clusters of molecules rush out into the bloodstream, shouting at the legs to run, pulling blood away from its other work, away from gut and face and the many places of daily chores, into the trembling muscles of the thighs, and we call this fear. Coagulants crowd around the broken tissues, making bruises but preventing hemorrhage.  At the same time the synapses of memory summon up images of other beatings, layers of them: clubs that struck the same body, that struck the body before this one, since all cells except the brain shed over the course of seven years, like a slow forest where it is always autumn and spring together Clubs that struck others in our sight, clubs we heard about, historical clubs, the memories of which coat the surfaces of strands of DNA like slick oil, epigenetically instructing the body that the club is always falling, because in some generation before us, neither fight nor flight was possible or complete, and an ancestral body remained flooded with cortisol, shuddering with it, subtly altering the methyl layers of its genes. So, whether or not the club is still falling, parts of the guanakan still tremble with norepinephrine, images of past dangers still crowd what we call the inner eye, imagination and flesh collaborate to tell a story in which past and present are woven together into a composite, layered diagram of what is happening in the eternal now, and worst of all, what can be expected. My guanakán suffered a series of invasions, which set up a repeating story of danger, which in turn shaped the behavior of the guanakán. My guanakán also inherited a huge stack of orders from the past, many of them meant to help with survival, the way sickle cells are meant to help with malaria but create so many other problems. Some of the orders are inexplicable. Random scramblings of genetic code. It’s hard to tell, because they have been translated from the original, passed through many hands, become smudged. They are incomplete fragments of an indecipherable past, coded inheritances, made up of traumas and unpredictable changes and cross pollinations.

At the same time the synapses of memory summon up images of other beatings, layers of them: clubs that struck the same body, that struck the body before this one, since all cells except the brain shed over the course of seven years, like a slow forest where it is always autumn and spring together Clubs that struck others in our sight, clubs we heard about, historical clubs, the memories of which coat the surfaces of strands of DNA like slick oil, epigenetically instructing the body that the club is always falling, because in some generation before us, neither fight nor flight was possible or complete, and an ancestral body remained flooded with cortisol, shuddering with it, subtly altering the methyl layers of its genes. So, whether or not the club is still falling, parts of the guanakan still tremble with norepinephrine, images of past dangers still crowd what we call the inner eye, imagination and flesh collaborate to tell a story in which past and present are woven together into a composite, layered diagram of what is happening in the eternal now, and worst of all, what can be expected. My guanakán suffered a series of invasions, which set up a repeating story of danger, which in turn shaped the behavior of the guanakán. My guanakán also inherited a huge stack of orders from the past, many of them meant to help with survival, the way sickle cells are meant to help with malaria but create so many other problems. Some of the orders are inexplicable. Random scramblings of genetic code. It’s hard to tell, because they have been translated from the original, passed through many hands, become smudged. They are incomplete fragments of an indecipherable past, coded inheritances, made up of traumas and unpredictable changes and cross pollinations.

My guanakán, already attuned to danger by invasion, has been gifted with nine CYP 450 polymorphisms, nine disturbances in the field of protection. Diesel fumes and tobacco, charred protein and estrogen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and blood thinners, phenobarbitol and bacon, all move differently through the guanakan, more slowly, leaving more damage in their wake. This is what I have inherited. Tiny broken places, gateways to change. We are all of us full of unfinished stories, fragmented instructions, maps to places that may or may not exist any longer, new and ingenious responses to a changing environment, some of them life-saving, some of them sickening, some of them fatal, life continually exploring new pathways in the guanakán. We have lost a great deal of early knowledge about how to guide those explorations and other knowledge we are only now seeing sprout above the soil line of our collective questions.

We are all of us full of unfinished stories, fragmented instructions, maps to places that may or may not exist any longer, new and ingenious responses to a changing environment, some of them life-saving, some of them sickening, some of them fatal, life continually exploring new pathways in the guanakán. We have lost a great deal of early knowledge about how to guide those explorations and other knowledge we are only now seeing sprout above the soil line of our collective questions.

This I know: the arc of a story must be completed or it stays in the guanakán and becomes a disturbance. It grows hard and dense and begins to have more mass, or becomes louder, alters the chemistry of emotion, the bones of belief on which we hang our perceptions, starts sparking, fluctuating, crackling, depending on where it expresses itself between matter and energy, particle and wave. A story whose arc is interrupted causes detours, must be stepped around, begins changing everything near it, has its own gravitational pull. Some of the unfinished stories we carry were forced on us: you are a person to whom it is right that these things be done. You a person to be raped, to be paid less, to be made to live downwind from terrible smokestacks that corrode your lungs. You are a person who cannot think very well, who burdens the rest of us by existing. Broken stories like these make blood run the wrong way, make breath shallow, fill the arteries with plaque, distract the antibodies from devouring cancer cells before they can form tumors and take over, cause the voice to shrivel, make the imagination flinch, generate heavy clouds of despair that reorganize our neurotransmitters. But the story of what is broken is itself something whole. These broken stories must be completed through our telling, our owning; like the roots of poisonous plants, they must be pulled up and laid in the sun to dry, so that by steeping, boiling, grinding, they can be made into medicine.

The body is a storyteller. Each act of illness is an epic tale about interactions of flesh, spirit, and environment, for which we have no language, since we have split existence into these three domains. Language, naming, is a way to make the overwhelming sensory flood of experience manageable, and for the sake of defining this against that, we distinguish things, separate them, hold them against each other, make culture and are made by it, and still the truth of our bodies lies in a realm language can’t fully grasp, because to speak truly means surrendering the categories on which we have built our sense of reason and control, categories that are the tools of our daily work, as practical in their uses as scissors and hoe.

The body is a storyteller. Each act of illness is an epic tale about interactions of flesh, spirit, and environment, for which we have no language, since we have split existence into these three domains. Language, naming, is a way to make the overwhelming sensory flood of experience manageable, and for the sake of defining this against that, we distinguish things, separate them, hold them against each other, make culture and are made by it, and still the truth of our bodies lies in a realm language can’t fully grasp, because to speak truly means surrendering the categories on which we have built our sense of reason and control, categories that are the tools of our daily work, as practical in their uses as scissors and hoe.

Consider skin: living in my skin, we say, jumping out of my skin, skin the boundary between us and not us, skin the receptacle of selfhood, skin, the percentages and shades of melanin, used to further shuffle and deal out the human deck, arrange us on a spectrum, dole out more and less of everything based on these degrees of difference in how we reflect light into each other’s eyes. We think skin is like the walls of our houses, that only sharp objects, or very hot ones, can open it, but skin is permeable. It isn’t the barrier between us and the world, it’s a conversation, cells lined up in a smooth collaboration, a layered surface that is constantly exchanging molecules with everything else. What’s more, a surface full of doors and windows, through which all kinds of wildlife passes. If skin is the wall of a house, that house is made of dried grass, is full of insects and small mammals and nesting birds, is its own habitat, constantly shedding stalks, or, to change the metaphor, is made of soft wood, growing mosses and mushrooms on its surface even as the shredded bark and wood fall away into the rich surrounding soil. Like anyone whose life depends on being heard, our bodies tell their stories over and over and louder and louder until they are shouting, spewing symptoms. But wait. There’s that word body again, with its lie of separation. And yet it’s far too bulky to keep saying body-mind-nature-thing. So, I am renaming it here and now. I will call it guanakán which is constructed from Taíno language parts to mean “our center,” that cloudy gathering of denser particles and pulses in which our awareness exists. Our location. From now on, when I say guanakan speaks, when I hand it to you, take it to be a basket in which everything we think of as body and mind and spirit and ecosystem coexist, and often, but not always, are each other. Well, then guanakan must tell its story. It does so without conscious decision. Storytelling is its being. When a hard object, denser than flesh, strikes flesh—a billy club, say—the strands of light and protein we call nerves begin winking and flashing their signal, telling receptors everywhere “something is harming us” which we call pain, and clusters of molecules rush out into the bloodstream, shouting at the legs to run, pulling blood away from its other work, away from gut and face and the many places of daily chores, into the trembling muscles of the thighs, and we call this fear. Coagulants crowd around the broken tissues, making bruises but preventing hemorrhage.

Consider skin: living in my skin, we say, jumping out of my skin, skin the boundary between us and not us, skin the receptacle of selfhood, skin, the percentages and shades of melanin, used to further shuffle and deal out the human deck, arrange us on a spectrum, dole out more and less of everything based on these degrees of difference in how we reflect light into each other’s eyes. We think skin is like the walls of our houses, that only sharp objects, or very hot ones, can open it, but skin is permeable. It isn’t the barrier between us and the world, it’s a conversation, cells lined up in a smooth collaboration, a layered surface that is constantly exchanging molecules with everything else. What’s more, a surface full of doors and windows, through which all kinds of wildlife passes. If skin is the wall of a house, that house is made of dried grass, is full of insects and small mammals and nesting birds, is its own habitat, constantly shedding stalks, or, to change the metaphor, is made of soft wood, growing mosses and mushrooms on its surface even as the shredded bark and wood fall away into the rich surrounding soil. Like anyone whose life depends on being heard, our bodies tell their stories over and over and louder and louder until they are shouting, spewing symptoms. But wait. There’s that word body again, with its lie of separation. And yet it’s far too bulky to keep saying body-mind-nature-thing. So, I am renaming it here and now. I will call it guanakán which is constructed from Taíno language parts to mean “our center,” that cloudy gathering of denser particles and pulses in which our awareness exists. Our location. From now on, when I say guanakan speaks, when I hand it to you, take it to be a basket in which everything we think of as body and mind and spirit and ecosystem coexist, and often, but not always, are each other. Well, then guanakan must tell its story. It does so without conscious decision. Storytelling is its being. When a hard object, denser than flesh, strikes flesh—a billy club, say—the strands of light and protein we call nerves begin winking and flashing their signal, telling receptors everywhere “something is harming us” which we call pain, and clusters of molecules rush out into the bloodstream, shouting at the legs to run, pulling blood away from its other work, away from gut and face and the many places of daily chores, into the trembling muscles of the thighs, and we call this fear. Coagulants crowd around the broken tissues, making bruises but preventing hemorrhage.  At the same time the synapses of memory summon up images of other beatings, layers of them: clubs that struck the same body, that struck the body before this one, since all cells except the brain shed over the course of seven years, like a slow forest where it is always autumn and spring together Clubs that struck others in our sight, clubs we heard about, historical clubs, the memories of which coat the surfaces of strands of DNA like slick oil, epigenetically instructing the body that the club is always falling, because in some generation before us, neither fight nor flight was possible or complete, and an ancestral body remained flooded with cortisol, shuddering with it, subtly altering the methyl layers of its genes. So, whether or not the club is still falling, parts of the guanakan still tremble with norepinephrine, images of past dangers still crowd what we call the inner eye, imagination and flesh collaborate to tell a story in which past and present are woven together into a composite, layered diagram of what is happening in the eternal now, and worst of all, what can be expected. My guanakán suffered a series of invasions, which set up a repeating story of danger, which in turn shaped the behavior of the guanakán. My guanakán also inherited a huge stack of orders from the past, many of them meant to help with survival, the way sickle cells are meant to help with malaria but create so many other problems. Some of the orders are inexplicable. Random scramblings of genetic code. It’s hard to tell, because they have been translated from the original, passed through many hands, become smudged. They are incomplete fragments of an indecipherable past, coded inheritances, made up of traumas and unpredictable changes and cross pollinations.

At the same time the synapses of memory summon up images of other beatings, layers of them: clubs that struck the same body, that struck the body before this one, since all cells except the brain shed over the course of seven years, like a slow forest where it is always autumn and spring together Clubs that struck others in our sight, clubs we heard about, historical clubs, the memories of which coat the surfaces of strands of DNA like slick oil, epigenetically instructing the body that the club is always falling, because in some generation before us, neither fight nor flight was possible or complete, and an ancestral body remained flooded with cortisol, shuddering with it, subtly altering the methyl layers of its genes. So, whether or not the club is still falling, parts of the guanakan still tremble with norepinephrine, images of past dangers still crowd what we call the inner eye, imagination and flesh collaborate to tell a story in which past and present are woven together into a composite, layered diagram of what is happening in the eternal now, and worst of all, what can be expected. My guanakán suffered a series of invasions, which set up a repeating story of danger, which in turn shaped the behavior of the guanakán. My guanakán also inherited a huge stack of orders from the past, many of them meant to help with survival, the way sickle cells are meant to help with malaria but create so many other problems. Some of the orders are inexplicable. Random scramblings of genetic code. It’s hard to tell, because they have been translated from the original, passed through many hands, become smudged. They are incomplete fragments of an indecipherable past, coded inheritances, made up of traumas and unpredictable changes and cross pollinations. My guanakán, already attuned to danger by invasion, has been gifted with nine CYP 450 polymorphisms, nine disturbances in the field of protection. Diesel fumes and tobacco, charred protein and estrogen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories and blood thinners, phenobarbitol and bacon, all move differently through the guanakan, more slowly, leaving more damage in their wake. This is what I have inherited. Tiny broken places, gateways to change.

We are all of us full of unfinished stories, fragmented instructions, maps to places that may or may not exist any longer, new and ingenious responses to a changing environment, some of them life-saving, some of them sickening, some of them fatal, life continually exploring new pathways in the guanakán. We have lost a great deal of early knowledge about how to guide those explorations and other knowledge we are only now seeing sprout above the soil line of our collective questions.

We are all of us full of unfinished stories, fragmented instructions, maps to places that may or may not exist any longer, new and ingenious responses to a changing environment, some of them life-saving, some of them sickening, some of them fatal, life continually exploring new pathways in the guanakán. We have lost a great deal of early knowledge about how to guide those explorations and other knowledge we are only now seeing sprout above the soil line of our collective questions.

This I know: the arc of a story must be completed or it stays in the guanakán and becomes a disturbance. It grows hard and dense and begins to have more mass, or becomes louder, alters the chemistry of emotion, the bones of belief on which we hang our perceptions, starts sparking, fluctuating, crackling, depending on where it expresses itself between matter and energy, particle and wave. A story whose arc is interrupted causes detours, must be stepped around, begins changing everything near it, has its own gravitational pull. Some of the unfinished stories we carry were forced on us: you are a person to whom it is right that these things be done. You a person to be raped, to be paid less, to be made to live downwind from terrible smokestacks that corrode your lungs. You are a person who cannot think very well, who burdens the rest of us by existing. Broken stories like these make blood run the wrong way, make breath shallow, fill the arteries with plaque, distract the antibodies from devouring cancer cells before they can form tumors and take over, cause the voice to shrivel, make the imagination flinch, generate heavy clouds of despair that reorganize our neurotransmitters. But the story of what is broken is itself something whole. These broken stories must be completed through our telling, our owning; like the roots of poisonous plants, they must be pulled up and laid in the sun to dry, so that by steeping, boiling, grinding, they can be made into medicine.

Published on July 09, 2017 11:18

June 13, 2017

May 9, 2017

Mothers

I am of the generation of red diaper children that was raised on the songs of the Spanish Civil War, that brave international effort to stop the spread of fascism in Europe. As a six year old, my father had gone door to door collecting coins to support the International Brigades, units of mostly communist volunteers from Europe and North America, many of them Jews. It was one of the heroic stories of my childhood.

So, when, at the age of twelve, I began translating poetry from Spanish, I started with Pablo Neruda’s Spanish Civil War poems, España en el Corazon, and the first poem I chose was “Explico Algunas Cosas.”

You will ask, says Neruda, where are the lilacs, and the metaphysical blanket of poppies and the rain that often struck your words, filling them with pinholes and birds. I will tell you everything that has happened to me. Then he describes the neighborhood of Madrid where he lived, his house, brimming with geraniums, the marketplace with its heaps of bread, rows of fishes and ladles of olive oil, a city alive with the drumming of hands and feet, and beyond it, the dry, leathery face of Castille.

And one morning, everything was burning, and one morning, the bonfires leapt from the earth devouring beings, and since then fire, gunpowder since then, since then blood.

Eighty years ago this month, German planes also bombed the Basque town of Guernica, the northernmost stronghold of the Iberian anti-fascist resistance, and an important cultural center for the indigenous Basque people. It was early evening, on a market day. Most of the men were away fighting, so the crowd gathered in the town square was made up of women and children, trapped there because the roads and bridges out of the town had been hit first and turned into barriers of rubble.

I thought of them today, the people whose deaths Pablo Picasso brought to world attention with his most famous painting, and of Neruda’s poem about the bombing of Madrid. Traitor generals, he cried, look at my dead house, look at broken Spain.

I had been reading about towering flames rising over Nangarhar, about the ground shaking as if in an earthquake, of people at a distance knocked unconscious by the force of the blast. I was reading about impoverish hed tribal people whose fields were just destroyed, about high maternal and infant death rates and no medical care, about a border slashed through the land by British invaders, and a government that provides nothing but decade after decade of war.

The US military men who dropped this gigantic weapon onto the homeland of Pashtun farmers, in a show of strength to intimidate the world, called it the mother of all bombs. Bombs are not mothers.

The actual mothers of this beautiful, wounded world are taking one step at a time, trying to protect our children from an all-out war on life, and all too often are forced to grieve them. I think of the mothers of Guernica, the mothers of Viet Nam and Palestine and Syria and the Congo, the mothers of Buenos Aires and Detroit, Chicago and Ayotzinapa, indigenous mothers like Berta Caceres, mothers protecting rivers from Amazonas to Standing Rock, real mothers.

I have no punchline or moral to end this with. Neruda’s poem was a defense of political art, a declaration of conscience. He writes, You will ask why my poetry doesn’t speak of sleep, of leaves, of the great volcanos of my native land. And he answers, come and see the blood in the streets. Like Bertolt Brecht who wrote, “What a time it is when to speak of trees almost a crime, for it is a kind of silence about injustice,” Neruda seems to be saying that blood makes leaves and land irrelevant. But today we know that trees and rivers, land and sky are all swept up into the same struggle, between the cultivation of life and its destruction, between the practice of mothering this living planet and all its beings, a practice rooted in the heart, with or without a womb, and the so-called mother of all bombs.

And then words of a song begin to run like a thread of water through all this trouble, and I find an ending after all. I remember Linda Tillery singing an Eric Bibb song a couple of months ago at my synagogue: Time has come, enough is enough, got to move aside, let the mothers step up.

So, when, at the age of twelve, I began translating poetry from Spanish, I started with Pablo Neruda’s Spanish Civil War poems, España en el Corazon, and the first poem I chose was “Explico Algunas Cosas.”

You will ask, says Neruda, where are the lilacs, and the metaphysical blanket of poppies and the rain that often struck your words, filling them with pinholes and birds. I will tell you everything that has happened to me. Then he describes the neighborhood of Madrid where he lived, his house, brimming with geraniums, the marketplace with its heaps of bread, rows of fishes and ladles of olive oil, a city alive with the drumming of hands and feet, and beyond it, the dry, leathery face of Castille.

And one morning, everything was burning, and one morning, the bonfires leapt from the earth devouring beings, and since then fire, gunpowder since then, since then blood.

Eighty years ago this month, German planes also bombed the Basque town of Guernica, the northernmost stronghold of the Iberian anti-fascist resistance, and an important cultural center for the indigenous Basque people. It was early evening, on a market day. Most of the men were away fighting, so the crowd gathered in the town square was made up of women and children, trapped there because the roads and bridges out of the town had been hit first and turned into barriers of rubble.

I thought of them today, the people whose deaths Pablo Picasso brought to world attention with his most famous painting, and of Neruda’s poem about the bombing of Madrid. Traitor generals, he cried, look at my dead house, look at broken Spain.

I had been reading about towering flames rising over Nangarhar, about the ground shaking as if in an earthquake, of people at a distance knocked unconscious by the force of the blast. I was reading about impoverish hed tribal people whose fields were just destroyed, about high maternal and infant death rates and no medical care, about a border slashed through the land by British invaders, and a government that provides nothing but decade after decade of war.

The US military men who dropped this gigantic weapon onto the homeland of Pashtun farmers, in a show of strength to intimidate the world, called it the mother of all bombs. Bombs are not mothers.

The actual mothers of this beautiful, wounded world are taking one step at a time, trying to protect our children from an all-out war on life, and all too often are forced to grieve them. I think of the mothers of Guernica, the mothers of Viet Nam and Palestine and Syria and the Congo, the mothers of Buenos Aires and Detroit, Chicago and Ayotzinapa, indigenous mothers like Berta Caceres, mothers protecting rivers from Amazonas to Standing Rock, real mothers.

I have no punchline or moral to end this with. Neruda’s poem was a defense of political art, a declaration of conscience. He writes, You will ask why my poetry doesn’t speak of sleep, of leaves, of the great volcanos of my native land. And he answers, come and see the blood in the streets. Like Bertolt Brecht who wrote, “What a time it is when to speak of trees almost a crime, for it is a kind of silence about injustice,” Neruda seems to be saying that blood makes leaves and land irrelevant. But today we know that trees and rivers, land and sky are all swept up into the same struggle, between the cultivation of life and its destruction, between the practice of mothering this living planet and all its beings, a practice rooted in the heart, with or without a womb, and the so-called mother of all bombs.

And then words of a song begin to run like a thread of water through all this trouble, and I find an ending after all. I remember Linda Tillery singing an Eric Bibb song a couple of months ago at my synagogue: Time has come, enough is enough, got to move aside, let the mothers step up.

Published on May 09, 2017 10:59

March 23, 2017

Brain Journey: Day Four

Imagine you’ve been wearing dirty eyeglasses for years. You’ve adapted to the smudgy view of the world, and now that’s just the world to you. You muddle through and don’t bump into too many things. You just assume a certain amount of what’s out there is illegible. Then someone comes along and cleans the lenses with rubbing alcohol, and puts them back on your face.

How could you have imagined what you weren’t seeing? That leaves have crisp edges. That colors are not overlaid with dust. That almost everything IS legible. This is the metaphor of a highly visual person. There are many other. Imagine a loud vent fan has been running all your life and someone turns it off and you discover birdsong. Imagine you’ve had lead weights strapped to your legs and someone takes them off and you discover running.

The word for today is integration. I can feel left and right hemispheres in communication, feel the central exchanges of the subcortical brain moving traffic through without slowdowns, feel orderly inside my head in a way I can’t really remember feeling, except I keep having this image of a bright eyed six-year-old who didn’t struggle with remembering words. I wish my parents were alive, and here to see this, to greet that child’s return.

These pictures were taken when I was 4-5, before the fall.

These pictures were taken when I was 4-5, before the fall.  This is me at the end of first grade, after the fall. We were living in Rochester, New York the year I was six. I shared a room with my brother Ricardo. I had the top bunk and he had the bottom. One night I rolled right over the retaining safety bar and woke up midair, falling, and then landed, hard, on my back, on a cement floor. It is only in the last few weeks that it’s occurred to me that there is no way to land on one’s back like that and not have a big cracking blow to the back of the head. But in those days, you had to have a skull fracture and blood everywhere to be considered head injured. The occupational therapist has been explaining compensation, and tells me that young brains are even better at this, loop out the injured arts and have the subs step in even more efficiently. So now it seems that my entire writing life has been managed from temporary quarters, by editors drafted from the gardening team of the kitchen crew, all of them running as fast as they can with big bags of stuff slung all over them.

This is me at the end of first grade, after the fall. We were living in Rochester, New York the year I was six. I shared a room with my brother Ricardo. I had the top bunk and he had the bottom. One night I rolled right over the retaining safety bar and woke up midair, falling, and then landed, hard, on my back, on a cement floor. It is only in the last few weeks that it’s occurred to me that there is no way to land on one’s back like that and not have a big cracking blow to the back of the head. But in those days, you had to have a skull fracture and blood everywhere to be considered head injured. The occupational therapist has been explaining compensation, and tells me that young brains are even better at this, loop out the injured arts and have the subs step in even more efficiently. So now it seems that my entire writing life has been managed from temporary quarters, by editors drafted from the gardening team of the kitchen crew, all of them running as fast as they can with big bags of stuff slung all over them.

But not today. Today I am feeling a clarity and focus that seem utterly foreign. I can pay attention to what I choose to, without struggling to shut out everything else. Everything else just isn’t that distracting anymore. Here’s another metaphor. It’s like living with a really messy roommate who just moved out and there are acres of clear, uncluttered floor, so that I have room to dance.

Tonight, I am getting ready for my last day, and the second fMRI that will measure the changes in blood flow in my brain, a concrete marker of improvement. I am also writing to the directors, telling them about their colleagues in Cuba who are eager to communicate, and asking about starting a scholarship fund. Most of the brain injured people I know are too poor to pay for this treatment, at least in part because they are brain injured.

Perhaps only the people with debilitating chronic fatigue will know what I mean when I say this. I am tired, but not exhausted. It’s an ordinary tired that is side by side with being energized. What’s missing is the deep weariness that it seems has at least in part been the result of decades of my injured brain pedaling as fast as it can in the wrong gear, and traveling inches for an effort that would carry another cyclist yards. Whatever is happening inside my head, my body is demanding protein in unprecedented amounts. Yes, it’s time for another meal.

How could you have imagined what you weren’t seeing? That leaves have crisp edges. That colors are not overlaid with dust. That almost everything IS legible. This is the metaphor of a highly visual person. There are many other. Imagine a loud vent fan has been running all your life and someone turns it off and you discover birdsong. Imagine you’ve had lead weights strapped to your legs and someone takes them off and you discover running.

The word for today is integration. I can feel left and right hemispheres in communication, feel the central exchanges of the subcortical brain moving traffic through without slowdowns, feel orderly inside my head in a way I can’t really remember feeling, except I keep having this image of a bright eyed six-year-old who didn’t struggle with remembering words. I wish my parents were alive, and here to see this, to greet that child’s return.

These pictures were taken when I was 4-5, before the fall.

These pictures were taken when I was 4-5, before the fall.  This is me at the end of first grade, after the fall. We were living in Rochester, New York the year I was six. I shared a room with my brother Ricardo. I had the top bunk and he had the bottom. One night I rolled right over the retaining safety bar and woke up midair, falling, and then landed, hard, on my back, on a cement floor. It is only in the last few weeks that it’s occurred to me that there is no way to land on one’s back like that and not have a big cracking blow to the back of the head. But in those days, you had to have a skull fracture and blood everywhere to be considered head injured. The occupational therapist has been explaining compensation, and tells me that young brains are even better at this, loop out the injured arts and have the subs step in even more efficiently. So now it seems that my entire writing life has been managed from temporary quarters, by editors drafted from the gardening team of the kitchen crew, all of them running as fast as they can with big bags of stuff slung all over them.

This is me at the end of first grade, after the fall. We were living in Rochester, New York the year I was six. I shared a room with my brother Ricardo. I had the top bunk and he had the bottom. One night I rolled right over the retaining safety bar and woke up midair, falling, and then landed, hard, on my back, on a cement floor. It is only in the last few weeks that it’s occurred to me that there is no way to land on one’s back like that and not have a big cracking blow to the back of the head. But in those days, you had to have a skull fracture and blood everywhere to be considered head injured. The occupational therapist has been explaining compensation, and tells me that young brains are even better at this, loop out the injured arts and have the subs step in even more efficiently. So now it seems that my entire writing life has been managed from temporary quarters, by editors drafted from the gardening team of the kitchen crew, all of them running as fast as they can with big bags of stuff slung all over them. But not today. Today I am feeling a clarity and focus that seem utterly foreign. I can pay attention to what I choose to, without struggling to shut out everything else. Everything else just isn’t that distracting anymore. Here’s another metaphor. It’s like living with a really messy roommate who just moved out and there are acres of clear, uncluttered floor, so that I have room to dance.

Tonight, I am getting ready for my last day, and the second fMRI that will measure the changes in blood flow in my brain, a concrete marker of improvement. I am also writing to the directors, telling them about their colleagues in Cuba who are eager to communicate, and asking about starting a scholarship fund. Most of the brain injured people I know are too poor to pay for this treatment, at least in part because they are brain injured.

Perhaps only the people with debilitating chronic fatigue will know what I mean when I say this. I am tired, but not exhausted. It’s an ordinary tired that is side by side with being energized. What’s missing is the deep weariness that it seems has at least in part been the result of decades of my injured brain pedaling as fast as it can in the wrong gear, and traveling inches for an effort that would carry another cyclist yards. Whatever is happening inside my head, my body is demanding protein in unprecedented amounts. Yes, it’s time for another meal.

Published on March 23, 2017 18:58

March 22, 2017

Brain Journey: Day Three

Many people are asking for more information, to better understand what I'm doing here, and today I got a much better grasp of it.

Today was piece after piece falling into its right position. Cascades of clarity, of things coming into focus. Memory, attention, vision.

Our brains have an easiest way to function, a path of least resistance. When there's injury, the hurt parts stop working well, and other parts rush in to pick up the slack. They compensate. They get the job or part of the job done. But it's very awkward and tiring. This is why it's possible for me to have a LOT of language functions that are barely working at all, and still be the writer and speaker I am. Other parts of my brain have been compensating. And this is also one of the main reasons I am so exhausted so much of the time. Compensating takes a lot of effort.

The activities we're doing in my sessions work the injured places so hard that the other parts can't compensate and give up, and the injured parts get reactivated. Once that happens, it doesn't need to be sustained. How these parts work when they're activated is what the brain wants to do, so it flows toward that. The brain scans that change after a week here, stay changed. They've had people come back a year later and the shifts have not reverted. Why would the brain do that, once it's back in sync? It's compensation that strains against the current, trying its best to keep things going because the wounded places can't. Reactivation IS the current.

This morning I had to memorize four numbers and then do a math operation on each one. Add or subtract the same amount to or from each one. I had to repeat the four numbers five or six times before I could remember them all and do the math. This afternoon I was asked to do it again, and I didn't need to repeat the numbers at all. I just did the calculations. The capacity was just there.

My vision is also clearer. It's neurological. When I'm asked to follow a pen side to side, my eyes skip and jump a lot. They have a hard time moving back and forth to different depths of focus.

When I read, I often find myself a few lines down from where I meant to be reading, and notice because it doesn't make any sense. So I spend a lot of time working my focus back and forth along a string, stopping at three different beads, looking at them so that it seems that two strings cross through their centers, then walking that X up and down the string. And something changes inside my head. I feel something shift. My eyes change. The world looks different.

Today's word is accumulation, these shifts adding up, one on top of the other, or cascading from level to level. One of the therapists explained to me that it's the striving that activates. That while I do the best I can and am trying to get it right, that's really not the ultimate point. What matters is working the injured parts to the tipping point of switching back on. The effects seem to ripple out through my head. Seemingly unrelated things that were hard become easy.

Many of the games and exercises out there do improve certain functions, but mostly by increasing compensation, which has a cost in other symptoms. What we're doing isn't training the brain. We're reigniting it.

When I was a child in the mountains of Western Puerto Rico, we celebrated the ancient pagan festival of Imbolc, Christianized as Candlemas, by building huge bonfires. This is what I'm thinking of now. As night deepened across the wild country of the mountainous west, flames would spring up, one after another, great flaring fires around which children danced and shouted CandeLAAAAria! proclaiming our glee that the tinder and matches and dry branches we'd gather with strenuous labor had all come together to catch fire and send leaping sparks up into the starry dark.

This is me on a dark hill, watching the sparks rising, and shouting.

Today was piece after piece falling into its right position. Cascades of clarity, of things coming into focus. Memory, attention, vision.

Our brains have an easiest way to function, a path of least resistance. When there's injury, the hurt parts stop working well, and other parts rush in to pick up the slack. They compensate. They get the job or part of the job done. But it's very awkward and tiring. This is why it's possible for me to have a LOT of language functions that are barely working at all, and still be the writer and speaker I am. Other parts of my brain have been compensating. And this is also one of the main reasons I am so exhausted so much of the time. Compensating takes a lot of effort.

The activities we're doing in my sessions work the injured places so hard that the other parts can't compensate and give up, and the injured parts get reactivated. Once that happens, it doesn't need to be sustained. How these parts work when they're activated is what the brain wants to do, so it flows toward that. The brain scans that change after a week here, stay changed. They've had people come back a year later and the shifts have not reverted. Why would the brain do that, once it's back in sync? It's compensation that strains against the current, trying its best to keep things going because the wounded places can't. Reactivation IS the current.

This morning I had to memorize four numbers and then do a math operation on each one. Add or subtract the same amount to or from each one. I had to repeat the four numbers five or six times before I could remember them all and do the math. This afternoon I was asked to do it again, and I didn't need to repeat the numbers at all. I just did the calculations. The capacity was just there.

My vision is also clearer. It's neurological. When I'm asked to follow a pen side to side, my eyes skip and jump a lot. They have a hard time moving back and forth to different depths of focus.

When I read, I often find myself a few lines down from where I meant to be reading, and notice because it doesn't make any sense. So I spend a lot of time working my focus back and forth along a string, stopping at three different beads, looking at them so that it seems that two strings cross through their centers, then walking that X up and down the string. And something changes inside my head. I feel something shift. My eyes change. The world looks different.

Today's word is accumulation, these shifts adding up, one on top of the other, or cascading from level to level. One of the therapists explained to me that it's the striving that activates. That while I do the best I can and am trying to get it right, that's really not the ultimate point. What matters is working the injured parts to the tipping point of switching back on. The effects seem to ripple out through my head. Seemingly unrelated things that were hard become easy.

Many of the games and exercises out there do improve certain functions, but mostly by increasing compensation, which has a cost in other symptoms. What we're doing isn't training the brain. We're reigniting it.

When I was a child in the mountains of Western Puerto Rico, we celebrated the ancient pagan festival of Imbolc, Christianized as Candlemas, by building huge bonfires. This is what I'm thinking of now. As night deepened across the wild country of the mountainous west, flames would spring up, one after another, great flaring fires around which children danced and shouted CandeLAAAAria! proclaiming our glee that the tinder and matches and dry branches we'd gather with strenuous labor had all come together to catch fire and send leaping sparks up into the starry dark.

This is me on a dark hill, watching the sparks rising, and shouting.

Published on March 22, 2017 18:32

March 21, 2017

Brain Journey: Second Day

Flowers and stems make a 3D shape of an airy brain, with pink and white blossoms against a black background. A long time ago, when I had the stamina to go backpacking, there would be this moment when the pack came off and for a while, I would feel incredibly light, buoyant almost because my body, having grown accustomed to struggling with the extra weight, had been suddenly released. yesterday, I spoke with the occupational therapist about what it's been like to accomplish what I have while living with multiple brain injuries, that it was like climbing a mountain with a hundred pounds of rocks on my back.

Flowers and stems make a 3D shape of an airy brain, with pink and white blossoms against a black background. A long time ago, when I had the stamina to go backpacking, there would be this moment when the pack came off and for a while, I would feel incredibly light, buoyant almost because my body, having grown accustomed to struggling with the extra weight, had been suddenly released. yesterday, I spoke with the occupational therapist about what it's been like to accomplish what I have while living with multiple brain injuries, that it was like climbing a mountain with a hundred pounds of rocks on my back. It's only the end of the first day, but I am buoyant, floating, light on my feet. I had ten different therapy sessions today. One of them is with a device called the Dyna Vision. It's a big black square on the wall, with concentric rings of buttons that light up. I ask the therapist what part of my brain we're working on now and he says it's the subcortical region, the most seriously injured. The Grand Central Station of information routing, where so many pathways pass through, delivering information , sending signal, handling traffic--except that mine doesn't.

At first, my task is just to whack the buttons as they light up. But it gets more and more complicated and challenging. Hit the red lights with my right hand and the green with my left. Now switch. Hit the lights while reading a story out loud. And then, do a side to side dance step while hitting the lights. At first they are lighting up at the same speed as my dance step rhythm, but soon they speed up and I am hopelessly snarled. I lose the dance steps or I lose track of the lights, and eventually I lose both and stand, immobilized by my inability to track the two tasks that feel impossibly contradictory. We stop. Then he says, "Now do it again."

And all of a sudden I can. I can do it. I'm not confused. I can FEEL the lights going on in a darkened section of my brain, long unused. I stand there as my brain changes. Then I am taken to a softly lit room with a big comfy chair where I put on headphones for brainwave entrainment. It takes me into a meditative state and lets everything rest. While I am resting, I see two images. First there is a dimly lit curved corridor, full of grip hazards and obstacles--boxes, toys, piles of stuff. Then suddenly the lights are on, the hallways are completely clear and clean and I am running along the curve.

This is toward the end of a day in which I've done two hour long cognitive therapy sessions, played brain games chosen for my specific profile of difficulties, and neuromuscular work to open us circulation through my neck and into my head. I start to notice other things. Yesterday I couldn't figure out how to upload two images for a t-shirt that needs to be ready in nine days. Today I did it over my lunch break . Things I learned in the morning cognitive session are affecting how I play games in the afternoon. My head feel clear, unfogged. I feel lighter. There's a sense of fizzing, tingling, of vines sending out tendrils, of everything waking up. It's springtime in my brain, and I feel in tune with the flowering fruit trees that line the streets of Provo.

I get home with only a few minutes to spare before the first of two check-in calls. I haven't eaten,I have to pee, I want to change my clothes, and I have to fix food for tomorrow, plus my cell just dinged that I have a text. Yesterday I would have felt overwhelmed, felt that each of these things demanded my attention at the same time. I would have dithered and fretted trying to figure out what to do first. Today I pause, think for a minute and then decide I will pee, put up dinner, then check my messages, then do as much food prep as I can til my call starts and let my friend know I'll need to eat dinner while we talk. I'm unruffled. I have a plan, a sequence. Organizing a clutter of individual tasks, ideas, objects into a structure is one of the hardest things for me to do. Or it was yesterday, when I had a hundred pounds of ricks on my back . But somehow during the day, I loosened the straps, and someone helped me set my backpack down on the ground. Today is only Tuesday. Imagine what Wednesday, Thursday and Friday will be like!

Published on March 21, 2017 18:45

March 20, 2017

Brain Journey: First Day

The word for today is vindication. After decades of being told I just need to be more disciplined, more organized, less flaky, that I just need to get it together, that I'm lazy, that the reason I don't get more done is that I think I'm entitled to a life of ease, which has made me weep from sheer exhausted outrage, today I sat across from a man who showed me exactly how heavy a load of cognitive rocks I've been hauling around for at least 34 years, exactly which circuits of my brain have been gasping for blood supply, and exactly how miraculous it is that I've been able, however haltingly, however stop and go, however exhaustedly, however poorly paid because after writing I have nothing left for marketing, that I've been able to carve out for myself a name and reputation as a public intellectual, a feminist, a writer whose words are taught and reprinted and translated into many languages, and in spite of ceaseless ablism, earned for myself widespread respect.

Each multicolored chart, representing one of the tests I took while lying in an MRI machine, underlines this truth. Again and again he points to the ways in which my brain has "flatlined" its capacity to do any number of things I've been telling the people around me I can't do, and which they keep expecting that I can, because most of the time, the things I struggle with are camouflaged behind my un-garbled speech and my fluency with the written word. He shows me the black lines that represent all those times I can't remember what you just said to me, can't remember if I sent that payment in or not, can't retrieve a word, a name, something I know perfectly well but can't find anywhere, cannot, for the life of me begin to remember where I put the crucial document I just spent months getting a duplicate of, can't, no matter how I try, pull the information I need through the great hub of my subcortical brain, am swamped in the hubbub of a crowded room, my brain on overload from trying to filter out all the background noise with a broken net, and walk smash into a geological scale upthrust of bedrock tiredness so dense that I can't speak at all, must wave my hands in the air and retreat to a closet, elevator, bathroom before my entire brain floods and I can't find my way home.

Tomorrow will be about starting to all those circuits back to life, about reestablishing blood flow to places that, like a limb bent too long, have fallen asleep. Tomorrow will be about sweat and tremble and push, and the painful tingle of reawakening. But tonight is all about me turning to face the two white male neurologists who in 1983 told me that I was not brain injured but instead had conversion hysteria born of the desire to avoid working and be supported by my partner, waving these colored charts in their faces and telling them, "You can kiss my cerebellum."

Each multicolored chart, representing one of the tests I took while lying in an MRI machine, underlines this truth. Again and again he points to the ways in which my brain has "flatlined" its capacity to do any number of things I've been telling the people around me I can't do, and which they keep expecting that I can, because most of the time, the things I struggle with are camouflaged behind my un-garbled speech and my fluency with the written word. He shows me the black lines that represent all those times I can't remember what you just said to me, can't remember if I sent that payment in or not, can't retrieve a word, a name, something I know perfectly well but can't find anywhere, cannot, for the life of me begin to remember where I put the crucial document I just spent months getting a duplicate of, can't, no matter how I try, pull the information I need through the great hub of my subcortical brain, am swamped in the hubbub of a crowded room, my brain on overload from trying to filter out all the background noise with a broken net, and walk smash into a geological scale upthrust of bedrock tiredness so dense that I can't speak at all, must wave my hands in the air and retreat to a closet, elevator, bathroom before my entire brain floods and I can't find my way home.

Tomorrow will be about starting to all those circuits back to life, about reestablishing blood flow to places that, like a limb bent too long, have fallen asleep. Tomorrow will be about sweat and tremble and push, and the painful tingle of reawakening. But tonight is all about me turning to face the two white male neurologists who in 1983 told me that I was not brain injured but instead had conversion hysteria born of the desire to avoid working and be supported by my partner, waving these colored charts in their faces and telling them, "You can kiss my cerebellum."

Published on March 20, 2017 17:08

March 16, 2017

Brain Journey: Part 1

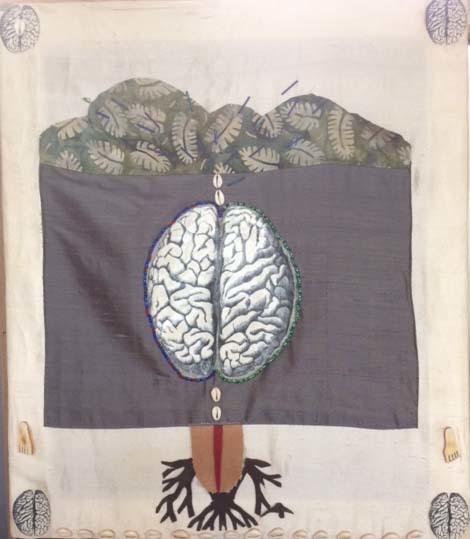

This is an image of my brain that I stitched, glued, and beaded during five days I spent connected to a Video EEG machine at UCSF. Those were only some of the many, many hours I've spent in hospitals from San Francisco to Boston to Havana, with people trying to decipher the injuries and idiosyncrasies of my brain. I have had six head injuries and a stroke as an adult, and I also fell from a top bunk onto a cement floor when I was six. Certainly since my first major adult head injury, when I was 29, I have felt each injury add its layers of difficulty to my daily life. The first one made me unable to do simultaneous interpreting from Spanish, although it was the only language I didn't stammer and halt in. After the third one, my hearing declined suddenly, but regular hearing tests didn't show anything. It wasn't until I was in Havana, years later, getting rehab for my stroke, that I had nerve conduction tests that showed significant damage to pathways from my ear to the part of my brain that processes sound.

This is an image of my brain that I stitched, glued, and beaded during five days I spent connected to a Video EEG machine at UCSF. Those were only some of the many, many hours I've spent in hospitals from San Francisco to Boston to Havana, with people trying to decipher the injuries and idiosyncrasies of my brain. I have had six head injuries and a stroke as an adult, and I also fell from a top bunk onto a cement floor when I was six. Certainly since my first major adult head injury, when I was 29, I have felt each injury add its layers of difficulty to my daily life. The first one made me unable to do simultaneous interpreting from Spanish, although it was the only language I didn't stammer and halt in. After the third one, my hearing declined suddenly, but regular hearing tests didn't show anything. It wasn't until I was in Havana, years later, getting rehab for my stroke, that I had nerve conduction tests that showed significant damage to pathways from my ear to the part of my brain that processes sound.