Penny Colman's Blog

January 31, 2020

Book Talk

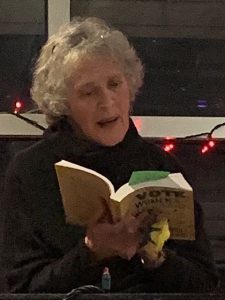

Last night, it was a bit of a drive, but well worth it to speak about The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight at Crosswicks Public Library, established in 1817, Crosswicks, NJ. Debbie Drachman, the library director, was wonderfully

welcoming. The audience was great. We arrived home late & I was hungry. Happily Linda remembered the big oatmeal golden raisin scone that we bought at a bakery in Harlem on Wednesday when we attended an Airbnb event by son Stephen, award-winning poet, playwright, producer, and director. Yum!

welcoming. The audience was great. We arrived home late & I was hungry. Happily Linda remembered the big oatmeal golden raisin scone that we bought at a bakery in Harlem on Wednesday when we attended an Airbnb event by son Stephen, award-winning poet, playwright, producer, and director. Yum!

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook. Click on images to enlarge.

January 24, 2020

Fun Event

Last night, 1/23/2020, I was a “very special guest” along with Judaline Cassidy, Feminist  Plumber, Activist, Trailblazer, and Founder of Nonprofit Tools & Tiaras, Inc.; Karrin Allyson, Jazz Vocalist & Pianist, 5x Grammy Nominee, Women’s Rights Activist; and Coline Jenkins, great, great granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton at a fundraising event— “The Women’s Rights Pioneers Statue & Suffrage Centennial Kickoff.” The statue, by sculptor Meredith Bergmann, representing Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony will be unveiled on August 26, 2020 in New York City’s Central Park.

Plumber, Activist, Trailblazer, and Founder of Nonprofit Tools & Tiaras, Inc.; Karrin Allyson, Jazz Vocalist & Pianist, 5x Grammy Nominee, Women’s Rights Activist; and Coline Jenkins, great, great granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton at a fundraising event— “The Women’s Rights Pioneers Statue & Suffrage Centennial Kickoff.” The statue, by sculptor Meredith Bergmann, representing Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony will be unveiled on August 26, 2020 in New York City’s Central Park.

Sandra Pimentel, the organizer & host extraordinaire, exuded contagious enthusiasm and passion. She was a marvel to watch as she gave introductory remarks and then introduced each of us.

After a Q & A session, Sandra asked me to read a selection from my book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. I chose an excerpt from the epilogue that ends with: “It is our obligation to permanently weave the names and deeds and lessons of suffragists into the national narrative of America so that this transformative fight remains a lodestar for present and future activists.”

After a Q & A session, Sandra asked me to read a selection from my book, The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight. I chose an excerpt from the epilogue that ends with: “It is our obligation to permanently weave the names and deeds and lessons of suffragists into the national narrative of America so that this transformative fight remains a lodestar for present and future activists.”

Top photograph L-R: Sandra Pimentel, Coline Jenkins, Judaline Cassidy, Penny Colman, Karrin Allyson. In the left side photo, I am answering a question. In the bottom right photo, I am reading from the epilogue. Photo credits: Linda Hickson (top); Charlotte Bennett Schoen (middle, bottom). Click on images to enlarge.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

January 13, 2020

Letter to Editor

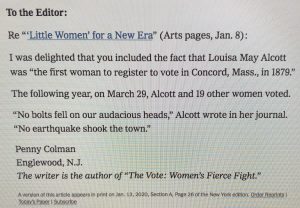

It was fun to wake up this morning and find that my letter to the editor re Louisa May Alcott and voting appeared in today’s The New York Times (Jan. 13, 2020, p. A26). It is also online at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/12/opinion/letters/antibiotics.html

Here’s an image that I photographed from my computer screen:

January 10, 2020

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Epilogue

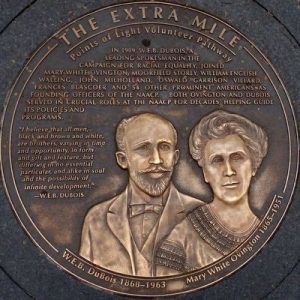

We must not rest. This statement by Mary White Ovington is the epigraph for the Epilogue in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight

About ten million women voted in the November 1920 presidential election. They came on foot, carriage, wagon, horseback, and in cars, including the popular Ford Model T. Pioneer suffragist Olympia Brown voted at the age of ninety-one. Sarah Penrose, who was “strongly opposed to suffrage,” felt it was her “duty nevertheless to vote.”

Across the country, however, there were women who were not able to vote. Women (and men) who were denied citizenship, such as Native Americas and immigrants of Asian descent, were prohibited from voting. A Richmond, Kentucky, newspaper reported that in Savannah, Georgia: “Negro women were refused ballots at voting places.” Efforts to curtail many citizens’ right to vote in America continue to this day, including impeding  registration, passing stringent voter ID laws, purging voters from the rolls, and limiting voting house. In words that resonate today, Mary White Ovington, a stalwart suffragist, journalist, and a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote that in the fight to protect the right to vote— We must not rest.

registration, passing stringent voter ID laws, purging voters from the rolls, and limiting voting house. In words that resonate today, Mary White Ovington, a stalwart suffragist, journalist, and a co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote that in the fight to protect the right to vote— We must not rest.

In the epilogue I dealt with two enduring questions: Why did it take so long? and How was the fierce fight of the vote won? I also write about the post-fight lives of a variety of suffragists, some sad.

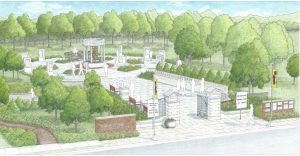

The centennial celebration in 2020 of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment has spurred efforts to  honor suffragists with a record number of landmarks, including the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial located near the site of the Occoquan Workhouse, and a statue in New York City’s Central Park representing Sojourner Truth,

honor suffragists with a record number of landmarks, including the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial located near the site of the Occoquan Workhouse, and a statue in New York City’s Central Park representing Sojourner Truth,  Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. A guide to landmarks aligned with the chapters in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight will soon available.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony. A guide to landmarks aligned with the chapters in The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight will soon available.

Image, top left: Bronze marker for Mary White Ovington and W.E.B. Dubois, another founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Points of Light Volunteer Pathway, Washington, D.C. Image, bottom right: Sketch of the Turning Point Suffragist Memorial, Occoquan Workhouse, southern Fairfax County, Virginia, architect Robert E. Beach, dedication in 2020. Image, bottom left, a rendering of the monument with representations of Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony (Click on image to enlarge.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 23

The vote is the emblem of your equality. This sentence by Carrie Chapman Catt is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 23, Justice Bell: August-September 1920

By August it was clear—the fight for the thirty-sixth state was down to North Carolina and Tennessee. On August 17 ratification by North Carolina legislators seemed possible, until the floor leader of the opposition made a deft move and got a resolution passed that deferred action until a regular meeting of the legislature in 1921. TENNESSEE SLENDER THREAD UPON WHICH SUFFRAGE HOPES HANG, warned a Chattanooga newspaper.  In Tennessee the Senate had already ratified the amendment. The House was scheduled to vote on Aug. 18. Abby Crawford Milton remembered that day, as “the most exciting and dramatic session ever held in the House.”

In Tennessee the Senate had already ratified the amendment. The House was scheduled to vote on Aug. 18. Abby Crawford Milton remembered that day, as “the most exciting and dramatic session ever held in the House.”

At 10:30 a.m., Speaker Seth Walker, an anti-ratificationist, banged his gavel to open the session, and soon moved to table the ratification resolution, a tactic to indefinitely suspend consideration. Harry Burn, who wore an anti-ratification red rose, vote “yea.” Banks Turner’s vote got lost in the din, although it appeared to some that he voted “nay.” The clerk began the second roll call. Again Burn voted “yea.” As the clerk continued through the alphabet, Seth Walker sat down beside Banks Turner, forcefully draped his arm over his shoulder, and urgently whispered in his ear. Suddenly, Turner shook off Walker’s arm, jumped to his feet, and shouted out his vote—”nay,” making the final tally a tie—48 to 48. The motion was defeated. The ratification resolution was still alive. Cheers and shouts resounded again and again from the pro-suffrage yellow rose side of the gallery.

moved to table the ratification resolution, a tactic to indefinitely suspend consideration. Harry Burn, who wore an anti-ratification red rose, vote “yea.” Banks Turner’s vote got lost in the din, although it appeared to some that he voted “nay.” The clerk began the second roll call. Again Burn voted “yea.” As the clerk continued through the alphabet, Seth Walker sat down beside Banks Turner, forcefully draped his arm over his shoulder, and urgently whispered in his ear. Suddenly, Turner shook off Walker’s arm, jumped to his feet, and shouted out his vote—”nay,” making the final tally a tie—48 to 48. The motion was defeated. The ratification resolution was still alive. Cheers and shouts resounded again and again from the pro-suffrage yellow rose side of the gallery.

The clerk started the roll call for the vote on ratification. Harry Burn, who had recently received a letter from his mother Febb Ensminger Burn, telling him to “be a good boy” and help Mrs. Catt with her “Rats,” voted “aye.” As did Banks Turner. The federal woman suffrage amendment was approved by a majority of 2: 49 to 47—victory, at last!

The clerk started the roll call for the vote on ratification. Harry Burn, who had recently received a letter from his mother Febb Ensminger Burn, telling him to “be a good boy” and help Mrs. Catt with her “Rats,” voted “aye.” As did Banks Turner. The federal woman suffrage amendment was approved by a majority of 2: 49 to 47—victory, at last!

On August 26, 1920, the U.S. Secretary of State signed the Proclamation of the Nineteenth Amendment. EQUAL SUFFRAGE IS LAW OF THE LAND, proclaimed a front-page headline in a Pensacola, Florida, newspaper. An elaborated ceremony was held in Independence Square in Philadelphia,  on September 25. The one-ton Justice Bell that Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger had commissioned in 1915, was rung by her niece forty-eight times, once for each state. Earlier in September, Carrie Chapman Catt had written in an article addressed to new women voters: “The vote is the emblem of your equality, women of America, the guaranty of your liberty . . . . Prize it!”

on September 25. The one-ton Justice Bell that Katherine Wentworth Ruschenberger had commissioned in 1915, was rung by her niece forty-eight times, once for each state. Earlier in September, Carrie Chapman Catt had written in an article addressed to new women voters: “The vote is the emblem of your equality, women of America, the guaranty of your liberty . . . . Prize it!”

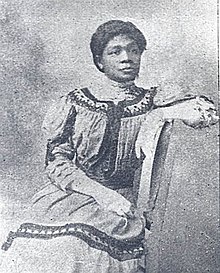

Top images: Frankie J. Pierce, founder of the Nashville Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. In May 1920, at a convention held in the Tennessee Capitol, she addressed an audience of all-white women, telling them “We are interested in the same moral uplift of the community in which we live as you are . . . .We are asking only one thing—a square deal. Middle right image: Tennessee Woman Suffrage Monument, Centennial Park, Nashville, unveiled August 26, 2016. The five women, represented by seven-foot tall bronze statues are: Frankie Pierce back left, Sue Shelton White, back center; Abby Crawford Milton, back right; Carrie Chapman Catt, front left; Anne Dallas Dudley, front right. Middle left image: Burn Memorial by Alan LeQuire representing Febb Burn and her son Harry Burn, Knoxville, unveiled 2018. Bottom image: the original Justice Bell, Washington Memorial Chapel, Valley Forge National Park. (Click on image to enlarge.)

January 9, 2020

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 22

Suffragists of the country, do not lay down your arms! This exhortation by Kenyon Hayden Rector, is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 22, Unite Again: January-July 1920

Thirteen states ratified the federal woman suffrage amendment by the end of March 1920.

In Oregon, where it had taken suffragists six referenda before winning equal suffrage in 1912, the legislature claimed it set a record by unanimously ratifying in thirty minutes. In West Virginia, legislators had waited in Charleston, while vigilant suffragists kept them from leaving town as the tie-breaking, pro-suffrage legislator, Jessie A. Bloch undertook a speedy return from his vacation in California.

In Oregon, where it had taken suffragists six referenda before winning equal suffrage in 1912, the legislature claimed it set a record by unanimously ratifying in thirty minutes. In West Virginia, legislators had waited in Charleston, while vigilant suffragists kept them from leaving town as the tie-breaking, pro-suffrage legislator, Jessie A. Bloch undertook a speedy return from his vacation in California.

In Oklahoma, a suffragist had sacrificed her life for the cause. Thirty-three-year-old Aloysius Larch-Miller died on February 2 in Shawnee. The day before, although ill with influenza, she had debated Attorney General S. P. Feeling, a skilled orator and fierce opponent of ratification, at a convention of Democrats. They had met to discuss a resolution requesting the obstinate governor to call a special session to vote on ratification. Larch-Miller’s “enthusiasm and eloquence” won the debate and convention delegates overwhelmingly adopted the resolution requesting a special election. The governor ordered the state flag to  be flown at half-mast. Resolutions were passed honoring her as “a martyr to woman suffrage.” Feeling was one of many dignitaries who attended her funeral. Children and local citizens raised money to create the Larch-Miller Park in Shawnee. The legislature ratified the federal woman suffrage amendment on February 28.

be flown at half-mast. Resolutions were passed honoring her as “a martyr to woman suffrage.” Feeling was one of many dignitaries who attended her funeral. Children and local citizens raised money to create the Larch-Miller Park in Shawnee. The legislature ratified the federal woman suffrage amendment on February 28.

The state of Washington, where women won equal suffrage in 1910, was the thirty-fifth state to ratify. One state short of ratification, the fight for final victory continued. The way ahead was fraught with frustration and futility.”Suffragists of the country, do no lay down your arms!” warned Kenyon Hayden Rector in her pamphlet “Women Awake!” The first woman licensed architect in Ohio and a member of the NWP’s Advisory Council, Rector urged, “You soldiers who held the cause dear, unite again for the final struggle.”

Top two images: Harriet “Hattie” Redmond, of Portland, Oregon, was one of many African American women who fought for their right to vote. In 2012, her superb organizing efforts were rediscovered, and this headstone was dedicated in Lone Fir Cemetery, Portland, Oregon. Middle image: the historica marker, a plaque attached to a boulder, reads: IN MEMORY OF ALOYSIUS LARCH-MILLER WHO GAVE HER LIFE FOR THE ENFRANCHISEMENT OF WOMEN.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 21

Telephone and telegraph wires were kept humming. This phrase by Ruth B. Hipple, is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VII, Chapter 21, Up to The States: June-December 1919

Anti-suffragists conceded that Congress had passed the federal woman suffrage amendment, but not that thirty-six states would ratify it. ANTIS LINING UP NEW FIGHT read the headline in a Seattle newspaper. The math favored the anti-suffragists. Ratification required approval by thirty-six of the forty-eight state legislatures, with just thirteen state legislatures needed to block ratification. The arduous and costly fifteen-month nationwide ratification campaign against dug-in, no-holds-barred opponents is  typically left out of the telling of the woman suffrage story, or told only through the final nail-biting campaign in Tennessee. The dramatic story begins in Chapter 21 of The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

typically left out of the telling of the woman suffrage story, or told only through the final nail-biting campaign in Tennessee. The dramatic story begins in Chapter 21 of The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight.

In South Dakota, the fight for ratification played out in the middle of winter and the dark of night. Ruth B. Hipple, the politically well-connected editor of a suffrage newspaper, got a tip that the governor was going to call a special meeting of the legislature to vote on ratification. She, in turn, alerted Mary “Mamie” Shields Pyle, president of the South Dakota Universal Franchise League, who mobilized her troops to hasten legislators to the capitol in Pierre. Ruth Hipple described the excitement: “Telephone and telegraph wires were kept humming for the next thirty-six hours and the men coming from all directions.” A man who lived far from a train station “used up three automobiles getting to the train . . . as the snow made the roads almost impassable.” On December 3, beginning at 7 p.m., the legislative process was quickly accomplished before adjourning, as was required. At one minute after midnight on  December 4, the next legislative day, legislators adjourned and unanimously ratified, in time for them to catch the trains that left in both directions.

December 4, the next legislative day, legislators adjourned and unanimously ratified, in time for them to catch the trains that left in both directions.

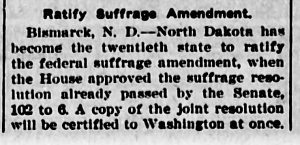

The final 1919 victory was in Colorado on December 15, 1919. Between June and December there were 22 ratification victories and 2 defeats. Images from top to bottom: An article about ratification in North Dakota appeared in The Keota News, Keota, Colorado, December. 5, 1919, p. 5; Alice Paul and the ratification flag appeared in The Sunday Star, Washington, D.C., December 28, 1919, p. 63. The caption reads: “When the Colorado legislature ratified the federal amendment granting suffrage to the women of the United States Miss Alice Paul, chairman of the national woman’s party, sewed the twenty-second star on the ratification flag at the headquarters in Washington.” (Click on image to enlarge.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

January 6, 2020

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VI, Chapter 20

At the dawn of woman’s political power in America. This phrase by Maud Younger, is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 20, On the Brink: March-June 1919

The chapter title, “On the Brink” reflects the fact that 271 years after Mistress Margaret Brent demanded and was denied two votes, it appeared that the Sixty-Sixth Congress would pass a federal woman suffrage amendment. It had to be re-passed by the House of Representatives and passed by the Senate. Representative James Robert Mann from Illinois, the man who had left his sick bed to vote for the amendment on Jan. 10, 1918, was the new chair of the House Woman Suffrage Committee. He assured Maud Wood Park, NAWSA’s chief lobbyist,  that he would get the amendment passed. And he did on May 21, 1919.

that he would get the amendment passed. And he did on May 21, 1919.

Now, the fight moved to the Senate. On June 3, 1919, a hot and humid day in Washington, D. C., the Senate Gallery was filled with suffragists. Confident of victory and eager to vote, only a few pro-suffrage senators spoke. Opponents voiced their anti-suffrage amendment tirades: states’ rights; fear of enfranchising “the dark sisters of the South”; and the “menace to the peace and welfare of the Nation.” Four amendments to the amendment, including one to enfranchise only white women, were voted on and defeated. On June 4,  the final roll-call began on a proposed amendment to the Constitution that read: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

the final roll-call began on a proposed amendment to the Constitution that read: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

The final vote was 56 yeas, 25 nays, just two votes more than required. Maud Wood Park “sat still trying to realize” that—”The end of the fight in Congress had come.” Maud Younger later wrote that she, along with Elizabeth Selden Rogers and other veterans of the fight, “walked slowly homeward, talking a little, silent a great deal. . . .We were at the dawn of woman’s political power in America.”

Images: From top to bottom: Banner headline, Great Falls Daily Tribune, Great Falls, Montana, May 22, 1919, p.1; double photograph, The Washington Times, Washington, D.C., June 5, 1919, p. 2. This is a rare, indeed, perhaps one-of-a-kind photograph pairing the two national woman’s suffrage organizations that had split in 1914 and employed divergent, sometimes contradictory, and often controversial strategies and tactics. Top caption: “Group of lobbyists of the National Woman’s Party and Senator Jones of Washington. These women conducted a six-year fight for the Federal suffrage amendment. From left to right: Mrs. William Kent, Mrs. Richard Wainwright, Senator Jones, Miss Maud Younger, Mrs. Abby Scott Baker.” Bottom caption: “Members of the Congressional Committee of the National America Woman’s Suffrage Association who presented the suffrage bill which was passed by the Senate yesterday. From left to right: Mrs. Mabel Willard, of Massachusetts; Mrs. Edmund Post, of Kentucky; Mrs. Helen Gardiner, of this city; Mrs. Maud Wood Park, of Massachusetts; Mrs. Lewis Walker of New Jersey; Miss Marjorie Shuler, of New York; Mrs. Caroline Reilly, of Illinois. The phrase in the bottom caption—”who presented the suffrage bill”—reflected the rivalry between the two groups as to claiming credit. In fact, both groups conducted strenuous and effective campaigns in Congress. It was Senator James Eli Watson from Indiana, the new chair of the Senate’s Woman Suffrage Committee, who “presented” the woman suffrage amendment for a roll-call vote. In the top image, Senator Jones, i.e., Andrieus Aristieus Jones from New Mexico, was the previous chair of the Woman Suffrage Committee. Note that Mrs. Kent, i.e. Elizabeth Thacher Kent, is holding an open fan. (Click on image to enlarge.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

January 5, 2020

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VI, Chapter 19

Where was my Uncle Sam. This statement by Louisine Havemeyer, is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 19, Escalation: January-March 1919

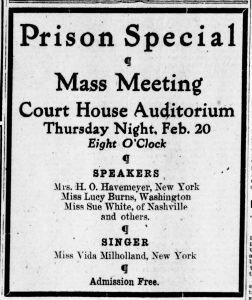

“No picketing and no prison for me, I don’t like the thought of either one,” Louisine  Havemeyer had “always laughingly” told Alice Paul who was thirty years younger than the sixty-four-year old Havemeyer. Nevertheless, when Alice Paul called and asked her to participate in a demonstration and pack a valise “in case we should have to go to prison,” Havemeyer left her three-story mansion that housed a world-famous art collection and a fleet of Rolls-Royce motor cars, and took the train from New York City to Washington, D.C. Paul explained that she planned to send a train, called the “Prison Special,” around

Havemeyer had “always laughingly” told Alice Paul who was thirty years younger than the sixty-four-year old Havemeyer. Nevertheless, when Alice Paul called and asked her to participate in a demonstration and pack a valise “in case we should have to go to prison,” Havemeyer left her three-story mansion that housed a world-famous art collection and a fleet of Rolls-Royce motor cars, and took the train from New York City to Washington, D.C. Paul explained that she planned to send a train, called the “Prison Special,” around  the country with speakers who had been imprisoned to arouse the public in support of a federal woman suffrage amendment. She wanted experienced speakers, and ones who would attract curious crowds and the press. Havemeyer, a prominent art collector, philanthropist, and a witty, down-to-earth, even risque speaker, fit both categories. But, first, she needed to be arrested.

the country with speakers who had been imprisoned to arouse the public in support of a federal woman suffrage amendment. She wanted experienced speakers, and ones who would attract curious crowds and the press. Havemeyer, a prominent art collector, philanthropist, and a witty, down-to-earth, even risque speaker, fit both categories. But, first, she needed to be arrested.

While leading a demonstration on January 9, 1919, Louisine Havemeyer was arrested along with thirty-nine other women. The next day, while the women waited in a jail attached to the courthouse for their trial, the U.S. Senate once again defeated the federal woman suffrage amendment, one vote shy of victory. Soon after the vote, the judge sentenced the women to a five-dollar fine or five days in jail. They chose jail. Much to their disbelief they were taken to the condemned jail where previous suffrage prisoners had suffered from breathing fumes of poisonous gases. Entering the “pestilential jail,” Havemeyer reported: “My very heart stood still for an instant and then bounded beneath my ribs and crackled as the sparks of indignation snapped within. Where was my Uncle Sam? Where was the liberty my fathers fought for? Where was the democracy our boys were fighting for?”

Other key events in Chapter 19 are the beginning of continual “Watchfire of Freedom,” or a fire on the sidewalk in front of the White House; the “Prison Special” tour; a demonstration and imprisonment in Boston; and the violence unleashed on suffragists in New York City at their Metropolitan Opera House demonstration, the last of the NWP’s “dramatic acts of protest.”

Other key events in Chapter 19 are the beginning of continual “Watchfire of Freedom,” or a fire on the sidewalk in front of the White House; the “Prison Special” tour; a demonstration and imprisonment in Boston; and the violence unleashed on suffragists in New York City at their Metropolitan Opera House demonstration, the last of the NWP’s “dramatic acts of protest.”

Image from top to bottom: Louisine Havemeyer with the Suffrage Torch (the chains holding the mobile speaker’s platform on the suffrage van are visible in the picture); an advertisement in a Chattanooga, Tennessee newspaper, The Chattanooga News (1/19/1919, p. 6) for the “Prison Special” that made fourteen stops during a three-week transcontinental train trip; a “Watchfire of Freedom” ablaze in front of the White House. (Click on image to enlarge.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

Epigraphs: The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Part VI, Chapter 18

We burn his words on liberty today. This statement by Elizabeth Selden Rogers is the epigraph for The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight, Chapter 18, Assault on Congress: October-December 1918

With the end of World War I in November 1918, President Wilson was attending the Paris Peace Conference in France. Fed-up with Wilson’s foot-dragging, tepid pro-suffrage- amendment politicking with Congress, the NWP escalated the burning of his words. On  December 16, 1918, four hundred women—”pioneer suffragists, munitions workers, women of the West, toilers, the unenfranchised women of America”—marched to the foot of Lafayette’s statue, across from the White House. A large Grecian urn rested on the base of the statue. Pine logs in the urn were set ablaze as Vida Milholland, the martyr Inez’s sister, sang the “Woman’s Marseillaise.” Elizabeth Selden Rogers, a founder of the NWP and a star speaker, spoke: “Our ceremony today is planned to call attention to the fact that President Wilson has gone abroad to establish democracy in foreign lands when he has failed to establish democracy at home. We burn his words on liberty today, not in malice or anger, but in the spirit of reverence for truth.”

December 16, 1918, four hundred women—”pioneer suffragists, munitions workers, women of the West, toilers, the unenfranchised women of America”—marched to the foot of Lafayette’s statue, across from the White House. A large Grecian urn rested on the base of the statue. Pine logs in the urn were set ablaze as Vida Milholland, the martyr Inez’s sister, sang the “Woman’s Marseillaise.” Elizabeth Selden Rogers, a founder of the NWP and a star speaker, spoke: “Our ceremony today is planned to call attention to the fact that President Wilson has gone abroad to establish democracy in foreign lands when he has failed to establish democracy at home. We burn his words on liberty today, not in malice or anger, but in the spirit of reverence for truth.”

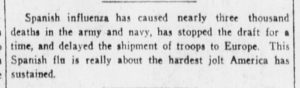

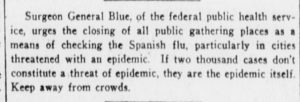

A dire circumstance complicated suffragists’ efforts in 1918—the outbreak of the influenza pandemic, dubbed the Spanish flu. Public officials shut public meeting places. The number of people on streetcars was limited. Some movie theaters sold half the number of tickets to reduce crowding. People wore gauze masks and kept their distances from each other. Bodies piled up in the street. Coffins were in short supply. In the eighteen months the virus ravaged America, an estimated 675,000 people died.

Despite the frightful, crippling conditions, suffragists conducted campaigns for equal suffrage in five states: Louisiana and Texas for the first time, Oklahoma for the second time, Michigan for the fourth time,

Despite the frightful, crippling conditions, suffragists conducted campaigns for equal suffrage in five states: Louisiana and Texas for the first time, Oklahoma for the second time, Michigan for the fourth time,  and South Dakota for the seventh time. At the federal level, Alice Paul orchestrated a picket assault on Congress, targeting anti-suffrage senators. Capitol police retaliated by manhandling the women. Newspapers across America covered suffragists and their fearless and persistent actions.

and South Dakota for the seventh time. At the federal level, Alice Paul orchestrated a picket assault on Congress, targeting anti-suffrage senators. Capitol police retaliated by manhandling the women. Newspapers across America covered suffragists and their fearless and persistent actions.

I write about suffragists’ activities and the opposition from October-December 1918 in Chapter 18. The images from top to bottom: Elizabeth Selden Rogers standing on a mobile speakers’ platform, holding a suffrage map. Behind her is a suffrage van stocked with suffrage literature and ephemera; two notices about the Spanish Flu from the Oklahoma City Times, Oct. 5, 1918, p. 10; South Dakota suffragist Rose Bower, on the cover of my book The Vote, was a suffrage lecturer, columnist, lobbyist, and musician renown for her skills in playing the cornet and whistling! (Click on images to enlarge.)

The Vote: Women’s Fierce Fight is available in paperback and eBook.

Penny Colman's Blog

- Penny Colman's profile

- 10 followers