V.R. Christensen's Blog

July 23, 2024

In the beginning…

No, not that beginning.

The other one. After the great burning. When God’s chosen vessel

came to take his rightful place upon the throne, ruling over all, at

long last, as He had promised.

But God works in mysterious ways, and that Utopia so many

had looked to with hope and anticipation, had yet to materialize. Such was the

fault of man who had not yet learned to trust with complete faith and with an

eye single to God’s glory.

The world was baptized once by water, and then, as foretold,

by fire.

And the phoenix rose with wings of flame and a golden halo.

After the wall was built.

After the refugees were expelled.

After supremacy of a pure race was reestablished.

After the alliance was broken.

After the planet was raped and plundered.

After the axis powers made that final assault.

We were left alone to be ruled by He who had come to save us all. Or so we believed …

Once upon a time.

July 22, 2024

I’m Still Here…

I have been quiet. I have been thinking. I have been grieving. Still. And trying to determine myself to some course of action that will render me once more purposeful and productive. And content.

The tenacity of this grief is an exhausting thing. It is a burden and a blessing. But more than anything, at least of late, it has been a preoccupation. I am treading water. Again. And my life is, month by month, week by week, day by day, passing me by.

I am fifty. Half way (more than half way, if I am honest with myself) between life and death. Do the first twenty years even count? I was a child. I was learning life, not living it. Not really. Not making decisions for my own about how I live and what I do and what my name should and would mean in the mouths of others. I’m fifty, and the losses that have seemingly paralyzed me over the last nine years are not the last I’ll experience. So why does my struggle seem so extraordinary? Is it? Or are we all walking around with these burdens and pretending we are fine? Is being an adult simply the day-to-day play acting as if we are too strong to feel or show or admit that our inner worlds are filled with lonesome suffering?

I recently read Carolyn Elliott’s Existential Kink. It’s premise is that the way to overcome many of our obstacles is not to try to avoid them, but to lean into them. By finding ways to take pleasure in the things we think we hate, we can overcome fears and roadblocks to our own progress. There are things in this life we can’t avoid: rejection, disappointment, fear, and shame. But leaning into those things teaches us precious lessons about ourselves. She spends a long time on shame, how shame warps our sense of self and actually makes the things we feel shameful about all the more tempting and exciting. Shame represses our secret desires and warps them into something that nags and pesters us in the moments we least expect.

There is a shame to grief, I’ve found. Having just passed the four year mark of my sister’s death, I feel an obligation to have “gotten over it” and to have moved on. I think about it less, certainly. But there is a resentment I feel toward that ever increasing distance between myself and her existence. In many ways I don’t want time to pass. In some respects I miss the newness of it, the feeling that she was just right there a minute ago. The acceptance that she is not coming back has well and truly set in. It is my reality now. I have moments when, after a long time of not having thought about it, the horror of it comes back to me. I have to work to put myself back in that place: waking up to missed phone (several of them) from the medical examiner’s office; the photos posted almost immediately by the news; the video posted to YouTube of flashing lights and broken glass, a dead dog, an overturned car … a body under a white sheet. Ambulances, and gurneys used and unused. How the driver, her husband, simply walked away. The witnesses, the lies, the pieces of conflicting information that don’t and never will add up. The answers we’ll never have. These are old news now, the shock of them worn dull and smooth, but heavy nonetheless.

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis talks about the embarrassment his desire to speak of his wife caused in those who also loved her. In the introduction to that book, his stepson, Douglas H. Gresham clarifies that embarrassment as shame inherent in the emotion he would undoubtedly show in the course of such conversations. Boys don’t cry. People of a certain class, of a certain education (and certainly of a certain gender) are meant to keep it together, to maintain composure, to preserve that “stiff upper lip.” But he also speaks of the opportunities missed to speak of his mother, to share that grief, and in grieving, hold her close again, even if only in memory.

Karla McLaren in her book The Language of Emotion refers to grief as “the deep river of the soul” (which I ironically discovered in my sister’s library and which is a beloved and well-worn book in my own library now). In her section on grief she talks about the human tendency to avoid grief, but in that avoidance, “we make the tragic mistake, and each death and each loss, because we don’t feel it honestly, just stacks itself on top of the last death or loss…” She speaks of the importance of leaning into grief, of moving down into it. “The movement required in grief is downward,” she reminds us. “When you move through grief in an intentional and ritual-supported way, you’ll feel pain, but it won’t crush you; your heart will break open, but it won’t break apart. … If you let the river flow through you, your heart will not be emptied; it will be expanded, and you’ll have more capacity to love, and more room to breathe.” She speaks of the importance of rituals that can be relived (think Dia de los Muertos rather than funerals that are done and over and never revisited) because grief doesn’t simply stopped. I sometimes say I luxuriate in emotion when allowed to do so, but Ms. McLaren almost encourages such things when it comes to grief. To move through it, one must feel it. Like an Existential Kink, grief is not something to necessarily be enjoyed, but there is an exquisiteness to it that brings us back into communion, if only for a short time, with those we have lost.

But the desire to avoid this downward dive into the emotional deep is strong. As I have recently been reminded.

In April I lost a friend to suicide. I always thought that those who took their own lives must be insane. What does it take, after all, bypass the innate and primitive need to preserve one’s own life? But I never knew anyone more sane than her. She had planned it for some time. She was deliberate and detailed, even going so far as to plan her own funeral. It has been a devastatingly sad experience, coming at a time when I feel a keen scarcity of close friendships. She was quickly becoming my new best friend. But I arrived too late. She had warned me, in a joking manner (of course) that she was could relate very well to the Barbie who experienced “irrepressible thoughts of death”. Her exit strategy was already on her mind. She prepared her clients, she made sure all was in order at work and at home, and she made her exit, like someone walking into another room and closing the door behind her. Only the door disappeared when she did. Is it that easy just to leave? I have been devastated by the loss of her, and yet there is a sort of strange comfort in the notion that this was what she wanted. I see her, her arms spread out wide in frustration: “Guys! This is what I wanted!”

And what do I want? I want to live. I want to experience life, its ups and its downs, its lows and its highs. But boy am I ready for some highs. I want to fall in love. I want to travel. I want to have a book published traditionally and see it for sale, stacked high on a table at Barnes and Noble. I want to be old and to look back on my life and think, I’m so glad I did not fear living!

But I think … I think my fear of living is, as Carolyn Elliott suggests, nothing more than the heads side of a coin that is my fear of pain and loss on the other. I’m not going to get over my sorrow by avoiding grief, by avoiding all the experiences that might cause me disappointment or heartache. I’m going to have to lean into it. For me that means writing. And I am keenly aware that if I do not make a real effort to save my writing career, I’m going to lose it. So I will be harnessing my grief, harnessing my anger, and finally, at long last, moving ahead with some of my writing goals (more on that soon). Suffice it to say, I have several things I’m working on, and hopefully … hopefully, some publishing news soon.

Until then, thank you for sticking around and following me on this journey, even when (especially when) I need to delve into the deeps and feel a little sad.

Blessings!

(and more soon)

December 5, 2021

Good Grief, it’s Complicated! (On the nature of grief and sorrow.)

“Human experience often brings such a complexity of emotions. Not since I was a small child have I felt anything unalloyed, not joy or anger or sorrow. For as long as I can remember, and more especially of late, I have experienced little else but the overwhelm of emotions that gather in crowds of mixed company.” ~ Fearless

My father was never what I would call healthy. Strong, yes, but not healthy. There was never a time I can remember when he was not in pain of one kind or another.

It was in 2003 when his health took a serious turn for the worst. He was diagnosed with esophageal cancer which bears a survival rate of something like 12-16%. I was asked to come home then. Not by him, of course. He was too independent for that, and my stepmother, at that time, was well enough to care for him. It was my sister who wanted me near. She was an hour from him in good traffic, but she could take some time off of work to help him get to his appointments and to sit nearby on his worst days. And they did get bad. I had just had a baby, and so my ability to travel was somewhat limited. My father pulled through it, though perhaps just barely. The ordeal proved a trial for my sister, and I think she bore a lot of resentment toward me for having to go through it alone.

In 2009, his health suffered another set back when his heart began to fail. He woke up one mourning and just felt he was seriously unwell. He waited for my stepmom to wake, and then he had her take him to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. They put him on diuretics and made plans to have a pacemaker inserted.

And then came the heart attacks. Only that’s not what they were in actuality. His pacemaker was equipped with a defibrillator and for some reason, whether it was because it was set to respond too readily to the slightest irregularity or if there was some other cause (working with his arms raised or around electrical impulses) it went off on him two or three times. Each time he thought it was the end.

And so it was that on Christmas eve of 2009, my sister called me (drunk) to tell me I needed to come home or it would be too late, that my dad was going to die and if I didn’t come home, I would not have the chance to say goodbye.

But I didn’t go home. My husband had just taken a new job in another state and I was alone in South Carolina with three children and a house to prepare to put up for sale. I couldn’t leave. I had to take my chances that the end was not so nigh as she feared it to be.

Just a couple of months later, I got a phone call. “Are you sitting down?”

“Yes.” I had been sitting on the floor, actually, working out how to rewrite the book I was getting ready to publish (my first). There were papers spread all around me, pens and highlighters …

She bore me the grim news. But I was sure I hadn’t heard it right. I stood. “Will you repeat that? I don’t think I heard you.”

“Jeff died.”

It was a blow I was unprepared for. You know from the time you are old enough to conceive of such things, that you will eventually lose your parents. To lose a sibling, though, … That is not supposed to happen. Not so young. He was 46. I was 37.

“How? What happened?”

“He collapsed in his driveway and hit his head. He’d been working on his car, and maybe he stood up to soon. It’s not clear. He went inside and laid down on the sofa. He asked JoAnne to call 911, and by the time they got there, he was gone.”

He had just gotten out of rehab. He had been told, and quite plainly (from what we later read from his journals) that if he drank again, it would kill him. And it did. Yes, he’d been drinking.

For awhile I was angry. I didn’t really process the loss right away. I had to be strong. I had children to care for, and who was there to care for me? No one. Women are caregivers, not carereceivers. There is a red line under the word as I write this. Do you know why? The word doesn’t exist.

Lisa was territorial about her relationships. After Jeff’s death, he became her brother more than mine. I bottled up my emotions and refused to process them. I had a book to rewrite. I had a house to finish and to pack up. I had kids to take care of.

And then one evening, we were watching a movie, and at the very end was a trailer for another movie. The track that scored it was Keane’s Somewhere Only We Know. I don’t know why that song. It was just that it hit me by surprise, and yes, I love Keane, but there was no special meaning to the song that would assign it to my brother’s memory. It just played, and I fell apart. I sobbed loudly, covering my face with my shirt out of shame. My husband was with us that weekend, and, characteristic to him, he quietly left the room, unable to tolerate that kind of emotional display. The boys stared at me in concern and surprise. My eldest came and sat with me and held me close, and let me spend the emotion I’d been holding in.

I later told my sister about this, but she took exception to the idea that I had some “secret place” I shared with my brother. I assured her it wasn’t the lyrics of the song that did it for me. I think it was just the band itself, and the way the song had come on so unexpectedly. My brother and I listened to much of the same music, and it felt like a hello from him. It still does, but I can’t tell you how or why (except that I really do believe in such things, and there doesn’t need to be a reason beyond feeling that it is so). She later criticized the way I had grieved for him, before and after that time. It was none of her business, really. But maybe that was her way of taking out on me the anger she felt at those in our extended family who had told her it wasn’t really so bad … he wasn’t our real brother, after all. But he was. He was my father’s son, and I loved him.

My grief for my brother was relatively simple. For a time I was angry that he chose to drink and therefore to die. I was disappointed in him. He had done such a bad job processing his compound disappointments. In many ways he was like my father, though, an addict, yes, but also a tortured boy growing up into a tortured man. He had something my father didn’t, though: the love of a devoted and adoring mother. I think he would have had that, but he was orphaned at the age of four. His parents, the ones that gave him life, loved him. I know that. The ones who adopted him, well … they tried, I suppose, but it was the 40’s, and a man needed to be toughened up not coddled. And boy did those boys learn to be tough!

Once the anger subsided, there was only love. Jeff was nine years older than me. We had different mothers. He never lived in our house, and I was lucky if I saw him twice a year. But I had no bad memories of him. He was never unkind to me. He never called me names or bullied me. He was always loving, nurturing, and very, very funny. My regrets are these: I didn’t try hard enough to stay close to him as an adult, I didn’t give him the time I should have, and I was never the confidant I might have been to him. Could I have saved his life? Probably not. But I certainly could have done more. But that is the true nature of grief. Grief is the love that remains, when those we have loved have moved on.

In 2015, my father was diagnosed with stomach cancer. I was at last in a position to help out. My marriage was ending, I was in the middle of an infatuation that was moving toward an affair if I didn’t do something drastic, and my father was dying. There was only one thing I could do. I could go to him. My stepmother had been diagnosed with dementia a few years before, and she was in no position to care for him. Not then. I could go. I wanted to go. And my father wanted me there, as well, another indication of how serious the matter was.

I won’t go into detail here about what that was like to be in Washington where I grew up and to care for him and for my stepmother as well, as that story will require several blog posts on its own. I was there for seven months. During that time, I got divorced, I ended and rekindled and ended again my relationship with my long-distance paramour–and learned things in the interim about myself and about him and my relationship habits that I have spent the last nearly seven years trying to resolve and amend. And I watched my father grow very, very ill and then, miraculously, recover. During that time I got to repair years of resentment and misunderstanding between my father and myself, and I got to spend some much needed time with my cousin and with my sister. But again, it was complicated.

Lisa resented my being there. She felt I had encroached on her territory. Everything I did was open to criticism, from what I did in my spare time to how much time I spent on my computer. I was still trying to write. It was and still is my best outlet and the thing that brings me the most peace. But I was also trying to learn about my self at that time. I was doing a lot of what my stepmom called “studying” reading every relationship book I could find, every “fix yourself” program I knew of. I was hurting and I wanted it to stop and, most of all, I never wanted to feel like that again.

In 2017, the cancer came back, and this time it was terminal. My father said goodbye to me over the phone. I remember sitting on the edge of the bathtub, locked in my one and only bathroom, and trying not to cry until I got off the phone. He had days. He was about to be put on palliative care–morphine–and would not be lucid again.

He lingered for almost a week, while my sister and my stepmother sat beside him. But neither of them handles stress or grief well, and they were at each other’s throats. My dad had asked me not to come. He didn’t want the trouble. He didn’t want the hassle. He just wanted to pass in peace and quiet. But after several days of sleepless nights and missed work, my stepmom and my sister said their goodbyes and left him. But neither did they want him to die alone. I got on a plane and arrived at the UW medical center at 10:30 pm. He was wasted and waxen … and old. He was 79, but he looked much older. Or perhaps, for the first time, I finally saw him as the spent man that he was. He had fought so hard, had battled seemingly insurmountable odds so many times. It was hard to accept that this was it.

I took my seat beside him. I said a prayer and sat down to meditate, but I didn’t speak to him. I was a little afraid of his knowing I was there. He had asked me not to come, after all. But when the nurse came in and asked me who I was, I told him that I was the daughter, come from Virginia, to take care of everything.

Four hours later, he slipped away quietly.

For as villainized as I was for making that decision to leave my family in Virginia to go to Washington and take care of my father, I have never once regretted the time I got to spend with him, the opportunity I had to make peace with him. I loved him, but our relationship was complicated. He wasn’t a very good father, and I often wondered if my brother resented us at all for his leaving him to start a new family with us. Jeff had it far worse, I know. If he did resent it, it never showed. My father had good qualities, too. He could be generous. And he was immensely talented. He was a gunsmith, a woodworker, a cook, a writer, and an artist. He could build anything, and he loved to learn new things.

My father’s death had an immense impact on my relationship with my sister. I spent a lot of time after his death not speaking to her. She felt wronged in so many ways. I got too much of his stuff after he died, I was there but not there, somehow. She liked to say “you never lived with him, so you don’t know.” Except I had lived with him, for seven months. She had spent the occasional night there after he married my stepmom, but she had never lived with him, so it made no sense. I feel like maybe it was something she needed to believe. She would also say “we helped him so much” during that time, but she was working. I don’t resent that, it was my turn, but … I was the one who did all the driving, the shopping, the medicating, the cleaning up. It was such a strange narrative she needed to maintain, that she was somehow more important in the scope of his life than even my stepmother was to him. It just wasn’t true, but in her mind it was irrefutable.

In the months just prior to her death, we had not been speaking. I had just had enough of the constant berating, the picking fights, the gaslighting and narcissism. I couldn’t do it anymore. I was learning (and still am) how to establish and maintain healthy boundaries for my own peace of mind, and so I had cut her off. But then, right around her birthday, she had gone in for emergency gallbladder surgery. I called her to see how she was doing. We talked a little, but she made it clear she was not ready to consider us friends again. Just a week before her death, we had begun texting. She was excited to start a new job, a job she would never show up to. It all ended so suddenly, so unexpectedly. We had JUST been talking! She had just been there a moment ago, and then … nothing but silence.

Silence.

And that is exactly what it feels like. She is there, but silent. Gone but not gone.

And it’s complicated. I’m angry. I’m angry she left so soon. I’m angry that we will never have the opportunity to be what we always should have been to each other–best friends. I’m angry that she lived a life of self-harm and blame and not taking the responsibility for her own problems. I’m angry at the constant criticism and judgment. I’m just angry. So angry. I’m angry that her husband has shut us out of his life, though I don’t blame him. I’m angry that it must now go to trial. There can be no closure, but neither do I want retribution. Her husband has suffered enough for the mistake he made that night which led to her death. There was no intention to do harm behind it, simply a lapse in judgment. Most of all, I just miss her. And I feel so, so alone.

I sometimes wonder if life is just an experience of subtraction. That we are meant to live amongst this crowd of loved ones and strangers, until we have said goodbye to every friend who has gone their own way and to every loved one that passes on before us.

Life is so quiet now. There is no one to tell me what a bad person I am, or how I am a bad friend, or a bad sister, or a bad daughter. I suppose that’s something to be grateful for. But mostly, I’m grateful to have loved, even when it was hard, or complicated, or painful. I have loved, and that is a gift.

November 1, 2021

Ellipses…

In my mind, we were in the middle of a conversation. That isn’t exactly how it was. She had told me she had some things she needed to get done. She was starting a new job in the morning, and she was really excited, but it was important she was feeling good and was prepared and well rested for her first day. She would go to bed early. Her regular bedtime was around 8.

So why she was out on the road at 9:30, I cannot figure out. She had wanted to show her husband her new place of work … that was what he told us later. But why then? Why at night when it was growing dark? Had she gone to bed and found she couldn’t sleep and so, maybe, thought an evening drive would help her relax? She sometimes took sleeping pills. They sometimes didn’t kick in right away. He sometimes took pills, too. He sometimes didn’t tell her.

Whatever it was that took them out that night, whether it was a leisurely pleasure drive to see her new place of employment or a quick trip to the store, they would not return for many hours. In fact, she would not return at all.

Where their drive took them, it is impossible to say. Perhaps he was telling the truth and they had gone to see where she would be starting work the next morning, but the medical office where she had been hired as a biller was located twenty miles to the southeast. The car came to rest, on its hood, a mile north of their house on the shoulder of a busy stretch of urban roadway.

There’s so much we don’t know and likely never will. What we do know is that the car was stopped for approximately ten minutes at an intersection just prior to the accident. A witness came upon it their Volkswagon from a different direction at a four-way stop. They waited for the car to turn or to drive on, but it just sat there. The witness went on to the store. Upon returning, the car was there still. Inside was a man—the driver—apparently asleep, a passenger who could not be seen clearly from the way they were slouched in the seat, and a dog. The witness sounded their horn, and the driver woke up and proceeded onward. Perhaps he had meant to turn there. Perhaps he fell asleep and, upon waking, forgot where he was or where he was supposed to be going. There was no mention of a signal. It was clear, however, to those observing the car, that the driver was not in a state to be driving. His speeds varied, sometimes well below the speed limit, sometimes significantly over. He weaved all over the road, occasionally crossing the middle line entirely. At one point he swerved off the road and struck something and then, correcting himself, continued onward, while the dog who rode as passenger—Charlie—ran from side to side and appeared to be trying to get out of one of the windows which was rolled down.

At the only point for miles where the road significantly turns, an oncoming car came into view. The driver swerved back into his own lane and, overcorrecting, drove onto the shoulder.

I can only assume the Passat was not the first car to have struck the mailbox that sat in front of the house situated on that curve of Waller Road. Between the house and the road, placed there, I imagine, to ensure that no car could intentionally or unintentionally knock the mailbox over, a pile of large landscaping rocks (the size you would use for a border, perhaps 12″ in diameter and irregularly shaped) were arranged around it and piled high. On the north side of the mailbox was a tree stump that might have been found as driftwood on a beach. It was not fixed, not part of a tree that had grown there, but found and given the dual purpose of decorating and protecting this artificial island where a mailbox stood.

I will say this, and I will say it again: Phone calls in the middle of the night are never good news.

“There was a car accident, and Lisa didn’t make it.”

Those were the words my mother heard when she answered the phone at 1:30 am. I would wake several hours later to find a multitude of messages, missed phone calls, and voicemails.

What we were told by my brother-in-law was that they were on their way home when he missed a curve and the car rolled over. He had been trying to keep the dog from jumping around, he told us. “Was Lisa awake?” I asked him later. “I think so,” he told me.” But why she was unable to keep the dog, a terrier, contained, I cannot fathom. She was very particular about the driving of others, about the safety of herself and those she travelled with, more particularly if she was not the one driving. She was not a particularly pleasant back-seat driver; she complained about everything from inconsistent speed to not slowing down gradually enough. Which raises the question: If she was awake, why was she so tolerant of his reckless driving? But I didn’t know enough then to ask the question. He made it sound as if the crash was slow and controlled. He made it sound as if the car ran into a ditch and just kind of rolled onto its top. Indeed, I do believe that was his perception. “How was it she didn’t make it?” was my mom’s first question. Mine was a little different, particularly after I watched the video footage of the wreckage and rescue. “How did he survive it?”

I watched that video footage more times than was wise or healthy. I saw things I can’t unsee. I saw her being cut out of her seatbelt and falling to the ground. Not her; her body. I saw them using saws to cut away the driftwood stump that was also flung dozens of feet and which the car partially landed on. I saw them with their jaws of life. And I saw him get out and walk away. I used to be grateful he survived. For a long time I blamed them both. Sleeping pills, Xanax, alcohol. I come from a family of addicts (my mother excluded). This is my normal. Alcohol and the necessity of swallowing down a lifetime’s worth of pain and anger are, I’m sure, contributing factors to the cancer that took my father not three years prior. My brother, too, was a victim of alcoholism. He died at the age of 46 (the age I was when I lost my sister). The story that I pieced together from comments made on the rescue video, from comments made by a friend of my brother who was also one of my sister’s suppliers, by clues I had pieced together: from occasions when she had forestalled one of my own panic attacks by handing me a benzo in the middle of an archeological exhibit, or the time I spent ten days with her and she slept the whole time was that they were both using, and they had gone out to get more—so that she could sleep. But now I’m not so sure.

When his toxicology came back he had significant amounts of fentanyl in his system. Hers was considered clean (though there was enough amphetamine to have allowed for a prescription dosage of Xanax.)

So now I’m not sure who I’m angry with. I would be a lot less angry if he would tell us the truth. I would be a lot less angry if he and his family hadn’t stopped talking to us (something I’m sure his lawyers have advised him to do). I’m trying not to care about her ashes or where they will go when he goes to jail. I’m trying not to care that we haven’t had a service because we have been waiting for those ashes. I’m trying not to be angry that the house is likely to go into foreclosure and I don’t know where all her thing will go or what will be done with them—among them are my brother’s journals, some art items my dad made, and some ceramics made by my grandmother. I don’t care about things, not really. But I do care about closure. It seems I will have to create my own.

This is my closure: I’m going to write, because that is what I do. I’m going to write about these last six years that have been both the most traumatic and the most incredible of my life. I’m going to write about my father’s illness and death, the end of my marriage, the destruction of my faith, my would-be love affair that never happened (though we all pretend it did because it makes it easy to identify someone to pin the blame on), my brother’s death, my sister’s death, and how it all ties together.

There is more I could say here. I could talk about how, three days after my sister’s death, she came to me. She was so angry. She was angry about the way she died, and she was angry about what we thought had happened. I don’t actually take that to mean I was wrong. She was always angry when I saw through her or when I knew she was doing something she shouldn’t. She liked to rewrite history. She liked to recount for me our own conversations and arguments and to cast them in a light that left her looking a lot less difficult and unreasonable than she actually was.

Maybe this isn’t the way we should talk about the dead. Perhaps my anger is as much for the opportunity I was robbed of to develop a relationship with my sister wherein I was not the designated bad guy as much as for the fact that she is gone.

She did come back to me a month or so after the event. She came to apologize. My father was with her. They were sorry for the way they had treated me in this life. It helped a lot … for a time. Forgiveness, after all, is a process and not a linear one, but, truth be told, I wanted those apologies when they were living. I wanted a relationship with her that didn’t involve drugs or alcohol. Maybe I have that now. Maybe I’m still waiting.

In my mind, the conversation was interrupted. In my mind, there are ellipses.

October 19, 2021

Summers’ End: A Tale of Madness (excerpt)

The third-story bedroom window overlooked the ornate gardens, the walk lined with neatly clipped boxwoods, and the tall wrought iron fence that divided Ravenswood from the rest of the world. It also offered a clear view of the doctors’ departure as the two gentlemen left the house by way of the cobbled walkway that led through the gate and to the street beyond, where two carriages waited. The first gentleman, eager to get to his next appointment, was quickly in the cab that waited for him and on his way. The second, stopping a moment at the carriage door, turned back to cast one last, reproachful look at the house before climbing in and giving the driver his directions. A moment later he, too, was gone.

Myra, still peering down from her bedroom window, observed her father as he stepped out onto the walk. He, too, watched as the carriages and their respective passengers departed. He had not been pleased by the results of the examination. The two doctors had failed to come to an agreement. And an agreement was necessary. If only he could find another doctor whom he could persuade to sign the certificate. And he would, Myra knew well. Whatever it cost him.

But Myra was not unwell. Her lowness of spirit, which the first doctor had declared to be a touch of melancholia, was deemed by the second to be nothing more than the strain of recent disappointment. It was true she had the occasional nightmare. It was true she sometimes talked in her sleep. But what the first doctor insisted were signs of mania, the second attributed to the loss of her mother, and then her longtime intended, in such quick succession. On rare occasion she lost her temper. She had once, imprudently, made some wild accusations in regards to her mother’s death, and had raved at her father in consequence of the sudden and unexplained renouncement of her intended’s proposal. Mr. Thorpe, as a result, feared she was suffering from fits of hysteria, and the first doctor had agreed. The second doctor, however, professed his belief that she was merely displaying the natural frustrations of a jilted heart bereft of the means to find consolation from a father who had no patience for female sentimentality.

But Mr. Thorpe insisted his daughter was as mad as was her mother before her. He knew the signs, he said, and he knew them well, for he had lived with them before. But the concurrence of two doctors was required in order to obtain the writ of commitment. Another doctor must be sent for.

And when might that be?

Myra’s father had returned indoors. Perhaps he was writing the letter even now. Perhaps before the day ended she would be on her way to an asylum, far away and off her father’s hands. He would dispose of her as readily and heartlessly as he had disposed of her mother. Where had he sent her? And what, exactly, had become of her? How she wished to have that question answered! And yet she dreaded to know at the same time.

…

The room was shaking. Or perhaps it was she who was being jostled about. Voices spoke in whispers above her head and all around her. She tried to sit up, to raise her head at least, but her body was so heavy she could not move. She was being poked and prodded—experimented upon. She’d had this dream before, but it was no easier to bear for it being familiar.

They were there, surrounding her, discussing her, arguing over the state of her mind and what was the best treatment to be tried. Ought they to attempt blistering? She might be bled, or leeched. She was not lucid enough to be spun or soaked in a tepid bath, but it might be worth a night in the tranquilizer chair if it meant preventing another episode of hysteria.

The voices grew lower, almost too low to hear. A question was asked. “No,” was the answer. “It’s too soon for that. Too risky. And if it should prove unnecessary after all…”

All grew quiet. The doctors had left. A faint pulsing remained in the air, a rhythmic rocking, the sound of a muffled metronome—a sort of clack-clacking—like that of a train’s wheels against the rails. It lulled her for a time, and her dreaming grew more peaceful.

…

The room was so dark she could not see her hand in front of her face. But she found, as she actually tried to do it, that though she could raise her hand before her, she could raise it no further, and to do so produced so loud a commotion of noise that she immediately abandoned the effort. Her heart pounded in her chest as she realized she was bound to her bed. She could move almost freely within it, but was prevented from rising from it. Each hand was shackled to her headboard, each movement sending the chains banging and clanging against the bed’s frame. Had she been moved in the night? And why would she be chained to the bed? Had John Wooding decided she was mad and restrained her for his own safety?

It was desperately cold in the room. A thin blanket covered her, but in her struggling it had shifted and now left her half exposed. She tried to readjust it with her legs, but every noise of her movement echoed in the dark. She was thirsty. Desperately so, and hungry, too. With one hand she felt around her bed, as far as the chains would allow her to reach, looking for the table that had been beside her bed just a few hours ago. Perhaps with her spectacles she might be able to see something, even in the darkness.

Though she could not find her eyeglasses, she did find a cup. She took a sip, and then another, and then threw the cup away from her with the realization it was badly soured milk. She retched over the side of the bed, but her stomach was too empty to comply. She lay for a moment, still and breathing hard, and trying to understand what had happened. She had gone to bed so comfortably, so happy and safe. How had she awakened to this? She tried once more to free her hands from their bonds. The noise shook the air.

“Quiet down in there!” a voice said, and the light of a lantern appeared, shining through a window, wavering in the air and lighting her room just enough to allow her a dim examination of her surroundings. Only it was not so dim; she could see remarkably well. It was a small room, perfectly square, with four gray and unadorned walls, and without a single window but the one situated in the top half of a heavy iron door. The voice was muffled and seemed to be attached to the lamp itself. Then the lamp moved, and the menacing face of a mustachioed stranger peered within.

“This is all a mistake. I should not be here! Let me out!”

He laughed. “To be sure. That’s what they all say! Be quiet, you, or I’ll call the doctor and he’ll give you something that will quiet you for a good long while.”

The light remained for a moment longer, and then retreated from the doorway to move along the corridor beyond.

Where was she? None of this made any sense at all. Dread and panic settled over her with the realization that, by some means she could not recall or imagine, and despite all her efforts to escape, she had been locked up in the asylum.

Wrestling once more against her bonds, she sent the air ringing with the echoing clatter and clang that had previously summoned the guard. She heard his footsteps once more approaching.

The lantern reappeared. The jangling of keys was heard, and the door opened. A bedraggled and impatient doctor entered, his eyes obscured behind the large lenses of his spectacles. An assistant accompanied him.

“Good evening, Miss Thorpe,” the doctor said. “Or is it Mrs. Thorpe? I forget.” He did not wait for her answer. She was not certain she could give it if he had, so confused was she. “It’s of little matter. When we get to know each other better, I will call you by your Christian name, as one would address anyone who behaves as a naughty child. And how are we this evening?”

“Where am I? How did I come to be here? I can’t remember.”

“Ah…” he said, as if that were the answer to his question. “A bit out of sorts, are we?”

“This is not right! There must be some mistake!”

“Yes, yes, of course there is,” the doctor answered sardonically. “Now I’m going to pour you a nice draught, and you’ll soon be off to sleep again.”

He examined the bottle through his thick spectacles, and made a face as he poured the dark liquid into a shot glass. She was determined that she would not drink it, however they tried to make her.

Resistance, however, proved futile. While the assistant held her head steady, the doctor forced her mouth open. The draught was administered. Laudanum. She coughed and sputtered and tried not to swallow, but her mouth was held shut now. There was no other option but to swallow or inhale and drown in it. She swallowed.

…

It was the smell she noticed first. Like human waste and unwashed bodies and vomit and opium. And it crowded in around her, like the noise that filled the air. She could see nothing. It was as if all four walls of the room were little more than an inch from her face. Try as she might, she could not move at all. She was sitting upright, her arms, legs, and torso strapped to a large and very uncomfortable chair. A box had been placed over her head. The closeness of it only magnified the screaming, the incoherent babbling that was all around her. Her chest hurt, her lungs were heavy, desperate for fresh air. And her arms… They ached so badly. Her wrists and ankles burned as she fought to free herself from the leather restraints. Her back, against the hard, oaken seat, felt bruised and raw.

She stopped her struggling to take in a breath, gasping for air, and nearly choked for the staleness and stench of it. It was then, in the silence of her breathing, that she realized it was she who had been screaming. It was her own incoherent ranting, though her voice sounded altered, deeper, raspy from ill use and frustration—older. Her lungs full, she began again. She wanted to stop. She knew what would come if she could not bring herself to be quiet. The leeches, if she were lucky. The bleeder’s knife that left scars on her wrists and arms. There was the chair, suspended from a ceiling, which was spun at maddening speeds until she vomited or lost consciousness. There were the burning cups that drew blisters, and the whip that stung and sliced.

And there was worse. Far, far worse. But these she had not experienced. Yet.

She must quiet herself!

But her body would not obey. Was this what it meant to be mad? Was it to be completely without control over one’s own thoughts and actions? If she were not mad already, such would surely drive her there. She wanted out—away! Was there no escape at all? She strained against her bonds, trying to make her wrists as small as possible. If she folded her thumb inward, even if it meant dislocating it, would that then allow her to pull her hand from the leather cuff? It might if she had the use of her other hand. It seemed quite impossible without it.

At last the door was opened. Of course he would come.

“Dr. Summers, help me,” she cried, and did not know how she knew with such certainty that it was he.

“Trust me, Myra. I am helping you.”

“I need to go home. I have to go home. This is all a mistake! I want to go home…” Her last words dissolved into wracking sobs.

“When you are better, Myra. When you are better, then you may return home. But you are a danger to others in this state. And you are a danger to yourself. Now let’s just give you something to calm you, shall we? And if tomorrow you are not quieter, perhaps we will try something a little more…persuasive.”

The box was removed from her head, and she saw him. His shock of white blond hair protruding out at odd angles. His eyes, huge and insect-like, were magnified grotesquely through the thick lenses of his spectacles.

He approached her, an insipid, simpering smile on his face. He held the shot glass to her lips, tipping it so she could sip the strong elixir. He did not need to force her this time. She drank willingly. It was the means, her only means, of escape. The opiate brought such pleasant dreams, dreams of friends who loved and cared for her, dreams of countryside cottages and places of safety and sanctuary. They were welcome dreams, happy dreams… Dreams she longed for, like the draught that freed her from the burdens of this reality, and swept her into a sanctuary of her mind’s creation. It did not matter that it was not real. It was real enough.

…

The slamming of a metal door awoke her. The rattling of keys followed, and soon one wrist was freed and then the other. She rubbed them in an attempt to get the blood flowing again but found that her skin was raw from the effort of trying to free herself. At least the wounds from her last bleeding had healed. Her legs were released as well, and the box removed from her head. She blinked as her eyes adjusted to the light, but it was impossible to make out anything but the vaguest impression of her surroundings.

“You have a visitor,” said the man who stood before. It was not the doctor but rather the guard.

“A visitor?” she asked, peering through squinting eyes. “Might I have my spectacles?”

“No spectacles allowed. You might hurt yourself.”

“Hurt myself? How?”

“You might cut yourself, try to do yourself in. Don’t tell me you haven’t thought about it.”

“I haven’t!”

She was raised from the tranquilizer chair, which was trundled out of the room, and given a clean gown to change into and a small bowl tepid water—not enough to drown herself in—with which to wash.

The guard returned with a pair of armchairs. Her bed was made up and pushed against the wall. A small table was brought, but no cloth and nothing to put on it. The guard left again, and when he returned, he brought with him her spectacles–and a visitor, Mr. Thorpe.

“Father!” she said, rising to greet him. And then remembering his cruelty: “Why have you done this? Why would you do this to me?”

“I understand you have not been behaving yourself,” he said, ignoring her question. “It does not surprise me, but I am nevertheless disappointed. Why won’t you let them help you, Myra? You know that as soon as you are well I can bring you home. Don’t you want that?”

“Do you really mean to bring me home, Papa?” she asked him, unbelieving. “If I’m good, do you promise I might be released from here?”

“Of course, Myra. If you are very good.”

“Or if I can prove I wasn’t mad?” “Myra,” he said and tsked at her. She wished she could see his face. She might make her way with him better if she could read his expression and what lay beneath it. She felt the helplessness of the situation, sensed that her father’s determination to keep her here was fixed. She slipped from the chair and fell to her knees before him, grasping onto his arm as she plead. “Please, Father,” she said, “… take me home. I’ll be ever so good. I’ll be a help to you. We might be so happy together, you will see!”

…

“My dear,” her father said with an air of concern that was too simpering to be sincere. “I fear your illness is more severe than I realized. Perhaps I should get the doctor. He’ll give you something to calm you, and then we can talk sensibly.” Mr. Thorpe rose, freeing himself from his daughter’s pleading grasp.

“No! Don’t go. Don’t leave me here! They will kill me if I stay!”

“Myra, this is nonsense,” he said, and raised his daughter up and placed her in her chair. “You must calm yourself. This behavior is most unbecoming.”

She was not doing a very good job of convincing him she was well, it seemed. She must calm herself. She must, at least, try harder to appear reasonable and unemotional, even if she did not feel it. “Please, sir,” she said. “I can be good. I was perfectly well behaved with the Woodings. They will tell you so if you ask them.”

Her father released a derisive scoff and rose to leave. “I’ll return, Myra, and you’ll see what a foolish girl you have been and how reasonably I have dealt with you.” He turned and was gone.

Myra sat and waited for the doctor to return, for him to chain her once more to her bed. But when the door opened a quarter of an hour later, it was not laudanum he brought with him this time, but a bottle that contained a thick syrup—an opiate in a more concentrated form. She did not argue this time, did not fight. She had learned by now that there was little point.

The doctor poured the thick syrup onto a large spoon, and the substance was placed into her mouth. She sucked the bitter syrup until the spoon was clean, but it was not enough, not nearly enough to satisfy her. She coughed and sputtered. The doctor, concerned, put his bottle down on the table and patted her back to ease her coughing.

“Forgive me,” she said. “I seem to have swallowed it wrong. Might I have a little water?”

The doctor nodded for the nurse to attend to the errand, and followed her as far as the door to watch for her return. The screaming and ranting of a female patient passing by in the corridor arrested his attention, and he stepped into the hallway to speak with the nurse who attended her. And while he was thus distracted, Myra took the bottle he had set upon the table and raised it to her mouth. Slowly the syrup ran onto her tongue and down her throat, swallow after sappy swallow. It kept coming, kept coming, and she kept swallowing.

A moment later, a gasp was heard. “Doctor! Look! The patient!” the nurse was heard to say. She dropped the cup of water she had brought with her, and it fell clattering to the floor as it spilled its contents.

“What have you done!” the doctor said. But it was too late. The opium was taking effect. The nurse and doctor both tried to raise her, with fingers down her throat they attempted to gag her into vomiting, but she was holding onto every drop. Others came to assist. There were so many, and they were so frantic and insistent that she could not ignore them. They were slapping her cheeks, dousing her with water. She opened her eyes, but the room was nothing more than a blur of hazy images. The doctor and his assistants were heatedly discussing what more they might try in their efforts to save her. Was it too late for syrup of ipecac? Might magnesium or charcoal be administered in time?

One nurse alone watched her. At first Myra observed her only from the corner of her eye as she removed her eyeglasses and held them in one hand. A moment later, the spectacles, one lens missing, dropped to the floor.

Leaving the doctor’s side, the nurse stooped to look more closely at the fallen object—at the bent wire frame, at the single lens that remained. And then something else dropped to the floor. One drop and then another. Little splashes of red.

Drop, drop, drop.

The asylum disappeared, fading away into the abyss of forgotten memory. Myra’s escape was absolute and final. She had returned to her beloved home—not to her father, no, but to that in which her mother resided, happy and safe in eternal peace and comfort, and no one and nothing could ever divide her from it again.

***Art by B. Lloyd. Excerpt from Summers’ End, published in 2013 as a short story in the collection, “16 Seasons”. Presently out of print.

October 1, 2021

A Ghost Story for the Ages

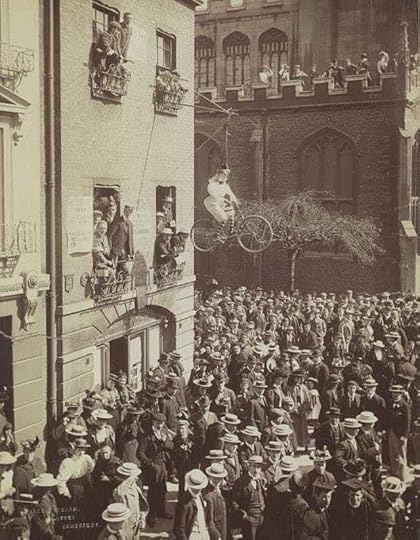

The summer of 1816 was a gloomy one. The devastating eruption of Mt. Tambora the year before had sent thirty-five cubic miles of debris into the air, which, by the following year, had made its way around the globe, casting a pall of darkness over the rest of the world. On the continent of Europe, storms were plentiful, skies were dark, and the rain fell for days on end.

Toward lake Geneva a group of poets and writers and fan-girls travelled, all for different purposes, but eventually converging at a villa rented by Lord Byron on Lake Geneva. Byron, travelling in an enormous Napoleanic carriage pulled by six horses made his way at a snail’s pace, was last to arrive, though he had been the first to leave. Traveling in the carriage with him was his personal physician John Polidori.

It was Claire Clairmont who led her party toward the spot where Byron might be found. Claire and Byron had been lovers for a period of some two months before Byron, bored of her as he inevitably grew of every amorous pursuit, had quit her with the same relish he had quit England and its crowd of debt collectors who had, the moment Byron departed, stripped his apartment bare of anything worth selling. Claire, it may be supposed, felt Byron owed her as he owed his debtors. She was pregnant, after all, and though she knew he would not receive her in Geneva, she knew he would not refuse an introduction to the celebrated poet with whom her Mary Godwin had recently eloped. Percy Bysshe Shelley was a rising star in the literary world, having achieved international acclaim for his poem Queen Mab. Claire managed to corner Byron as he was returning from a boating trip with Polidori and forced the introduction of the two poets. Byron happily received the introduction to Shelley alone and then and there invited him to dine that night, excluding Mary and Claire entirely. A jealous Polidori joined the men, though apparently reluctantly and was left to record the event, describing Shelley as bashful, shy, and consumptive, none of which was actually true, though Shelley was certainly intimidated by Byron’s talent and productivity.

Byron and Shelley immediately became close friends. Visits were paid between them while Percy and Mary stayed at a hotel on the other side of the lake from Byron’s villa. Byron rowed to visit them nearly every evening, despite howling winds and driving storms. After the weather threatened to sink his boat, he decided to take a villa closer–with in a ten minutes’ walk–from Percy and Marry.

As the poor weather persisted, their evenings were spent together reading, until, on one occasion, Byron turned the subject to ghost stories, acting them out as he read them and inflecting them with all the emotion and power inherent in his commanding presence and theatrical delivery, all the while his audience; Percy, Mary, Claire, and Polidori, did their duty by feigning fear and excitement (though one account describes Shelley in a fit after imagining himself to have seen two ghostly breasts appear from the darkness to stare at him condemningly). Byron, so pleased by the response to his reading, set his guests to a challenge: they would each write a ghost story for the delight and fright of each other. It was a sort of contest, to which each of the participants agreed enthusiastically and each immediately set upon the task of thinking up a story.

Byron had no trouble finding a place to start and wrote a full eight pages before growing bored and giving it up. Shelley, too, made an early start and began writing about his early life, but he, too, gave up the effort not long after he had begun it. Polidori, too, had an idea, one that Mary did not think much of, about a skull-headed woman who was cursed for having seen something she oughtn’t have. Finding such little encouragement from his companions, all of whom (save for Claire, of course) had some significant literary background, even if Mary’s own was that of her famous parents and not–not as yet–as a result of her own fame.

Mary, for herself, struggled to come up with an idea. Among the topics discussed between the party on those gloomy summer evenings were vampires, grave-robbing, and reanimation by means of electricity, including the scientific work of Luigi Galvani who had conducted some research on animal corpses in which he had demonstrated how, by applying electricity (via electrical storms), one could produce muscular contractions. The first spark of an idea came to Mary in consequence of a conversation between Shelley and Byron in which they were discussing “the nature and principle of life”, which recalled her once more to those ideas of Galvanism. She next began to wonder if a whole corpse might be re-animated and if, following that, a “a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.” She carried the idea to bed with her and there laid awake, allowing her ideas to form and develop until, at last, they conspired to produce a vision so vivid it was like a waking nightmare that she could not shut out. She saw the figure of a man “kneeling beside the thing he had put together … the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.” The creator of this monster, terrified by what he has done, then flees, hoping that the spark of life will extinguish itself. But doesn’t.

The idea so terrified Mary that she tried to escape it, forcing herself to think of other, more pleasant things. There was no sleeping now, late as it was, and though she was frightened still by the ghastly ideas she herself had invented, she had a sudden realization. She had thought of her idea for the ghost story Byron had challenged her to write.

Perhaps it was to her good fortune that Shelley and Byron went on a boating expedition for the next several days, leaving Mary, then only 18, to write alone and undisturbed, and so it was that she had made a good start before Shelley returned, at which time he read what she had written so far and gave it a favorable review, encouraging her to continue her work on it.

In December of 1817, the book was ready for publication. Its reception was mixed, but when Sir Walter Scott gave it a favorable review, the world began to sit up and take notice. Byron, of whom it has been said thought little of all women and if he loved any at all it was only his sister, Agnes, grew to admire Mary very much, and, long after Shelley died, she and Byron continued to have a friendship of mutual respect.

Polidori, eventually used and abandoned by Byron, would go on to write the Vampyre, one of the very first and seminal fictional accounts of such monsters, inspired by Byron himself.

It’s hard to believe that, after a fraught elopement (Percy was still married when he took Mary away), the death of his wife, their marriage, her husband’s fame, her literary accomplishment, the birth of four children and death of three of them, that the couple were only together a total of eight years (almost exactly) before Percy drowned in a boating accident in 1822.

Percy’s body was burnt on the beach of the Ligurian Sea where his body washed up 10 days after his drowning. It is said his heart did not burn and was carried back to Mary, who kept it in her desk until her death 30 years later.

Percy’s body was burnt on the beach of the Ligurian Sea where his body washed up 10 days after his drowning. It is said his heart did not burn and was carried back to Mary, who kept it in her desk until her death 30 years later.In May of 1824, Mary began a new novel entitled The Last Man. The following day, she learned of the death of Lord Byron. She was alone, save for her only surviving child, and she felt it.

The years that followed ushered in a societal and moral revolution. The death of King George IV and the succession of William IV marked a moment in time where people, feeling themselves exhausted by the debauchery of the long and bloody Regency Era, and in preparation for Victoria’s tight-laced reign (she was only eleven at the time, but those responsible for her training knew precisely what to prepare her to represent), made a conscious decision to turn common mores in the direction of moral retrenchment. Mary, wishing to give her son the security and respectability denied both her and Percy, set out to rewrite Percy’s story. Brought up by sexual revolutionaries and feminists herself, she had, and quite ironically, found herself tossed about on the whims of the stronger personalities around her. Now it was her turn to set the tone, and she could only do that by rewriting the narrative of the past. She did the same for Byron, editing his letters and journals and excising the bits that would not stand up to modern scrutiny. Of course we know today what Byron and Shelley were about. Even in their day they took things to extremes. It’s nevertheless interesting to consider the lessons that might be gleaned from these lives that burned far, far too brightly, and at the expense of the lesser lights–if one could consider Mary as such. The men around her certainly did. At 18, her creation of Frankenstein’s monster ought to have set her up as a genius of her day. But her book was, in many ways, a lamentation, a cry out to the world that the battle her parents had fought for the freedom they supposed was preserved to them only by shunning tradition and societal norms had been fought at the expense of the children they bore together. Mary was not only a casualty of her time, but of the people, men and women alike, who rowed the oars in the boat she had been set in, ultimately to sail in alone.

I’m not sure if her story, after all, is not more haunting than the tales she wrote.

***For further reading on this subject, I highly recommend the book The Monsters: Mary Shelley & the Curse of Frankensten by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler

August 21, 2021

On Manifestation part 1

Last month I talked about how I often take the issues that are troubling me and work them out in a fictional medium, but the reverse is also true. Sometimes I write things, and then those things seem to manifest in the real world. At the time that I began writing Absinthe Moon, there were the hintings and murmurings (at least amongst the Conservative crowd that then surrounded me) of political controversies and conspiracies. When have there not been, right? But I feel like much of what was proposed as possible during the Obama administration actually displayed itself as a real possibility during the administration that followed. Add to that a pandemic and climate change, and the world feels very much like a dystopian end-times novel about now. Except maybe more boring.

Foremost to my mind, and frankly the one that gives me the most internal disquiet, is the theme of vaccinations. Of course the controversies surrounding the issue are not new, but never has it been so forefront in world events. First let me say that I am not a anti-vaxxer. I firmly believe in the benefits of preventing avoidable death and illness from common diseases. What concerns me is the for-profit nature of the medical healthcare industry. But even that is not why I wrote vaccinations into the story. Really it was just a convenient way of saying that this culture of New Londinium and the patriarchal and elitist/ablest way in which it is run and maintained, is impregnated into the psyches of everyone who lives there. Even for those in the know, even for the most self-aware, prejudism, ableism, misogyny, racism are truly engrained into our paradigms. We can we are not any of those things, but until we have stood in the shoes of someone who has been injured by these things, we really can’t understand in what ways our mindsets are unnecessarily or unequally biased towards our own best interests. Simply saying you don’t agree with these things isn’t quite enough. It’s necessary to really examine them and consider in what ways we can do better.

But really the theme of vaccinations is multi-layered. There is also the idea of being forced to inject or ingest or metabolize something we didn’t intend to and would not have chosen to do on our own. I think of the “mickeys” slipped to unsuspecting women in bars, or the “one last drink” method of liberating a woman’s mind, quite against her better judgment and interest, even if it isn’t absolutely against her will, with any mentally lubricating substance so that, if she isn’t more likely to say “yes” at the end of the night, she is at least less likely to say “no”. Only what happens if this is not just the norm within a dating scenario, but the government and society as a whole is implementing such a device on the unsuspecting? I mean, if a power has the opportunity to control everything that is put into you for the sake of their own profit, then why wouldn’t they? Right? And it’s not that I totally believe this is happening, I just think it could. And what if?

Are these inoculations, in the way that they are set up in Absinthe Moon, a metaphor for rape? Possibly. Are they a metaphor for power and domination and control? Definitely.

On a different topic, I had to laugh when I wrote about the Warehouse Conservatory as a means of ensuring that the Resistance has uncontaminated food, and then just weeks later, the city where I live announced the construction of a state-of-the art indoor farming facility. That, to my mind, is really cool. Now when will be see the waste-to fuel plants implemented? Of all the things I invented in this book, the Great Forge and its technology was not one of them.

The discoloration worn by the citizens of New Londinium was intended to be a metaphor, of course, for the issues of prejudice surrounding race, which topic has certainly been thrust into the spotlight in the last year or so. It’s also a statement about cultural attitudes toward beauty and the intersectionality between ableism and elitism. It’s also, in a way, a revisitation of themes Oscar Wilde addressed in the Picture of Dorian Grey (which book I love, by the way.)

There are many other themes that either seem to have risen to the forefront of the cultural stage since I wrote this book, or which, perhaps, I have only become more aware of, and I’ll add to the list as I think of further examples.

In my most recent read-through, during the final proofing process of the paperback for Odessa Moon, it struck me as significant that the topic of “male likeability” is as prominent in the book as it is, when the topic seems recently to have been introduced, at least on social media, into the dialogue of those presently reassessing our cultural paradigms (a really valuable thing, I think). And I’d just like to add here that if you are one who doesn’t like the tone of these self-reflective cultural reassessment that is going on, (though if you do feel that way, I doubt very much you’ve read this far) then let me just say that the reason I think the conversation is important is, in part because it teaches us in real time how to adjust the way we think about our culture and our times and how we communicate about them. Nothing has been decided except to say that we know we can do better. What that better will look like is, as yet, undecided. Hence the need for conversation.

This is a demon.

This is a demon.I had never actually given it a lot of thought before, how history and the advancement of women’s rights has changed the dynamic between men and women so that we no longer marry because we “need” men in the traditional sense. When I was born, women had to have a husband’s permission to own a credit card, to make medical decisions about herself, to engage in a legal transaction, to have enough money to live. So many women married simply to survive and to have their material needs provided for. Now we don’t even need men to legitimize sex and childbirth. That need negated a lot of the character traits that women now required to be tempted into a commitment. If I have to marry to survive, probably I’m dreaming of true love, but, failing that, I’ll accept someone I don’t hate. It also means that the possibility of being alone for the rest of my life is very real because I’m quite happy doing for myself. What I need in a partner is kindness and affection and forthrightness and a good sense of ethics and fairness. Men now have to work to be likeable. And truly, I don’t mean to say that men generally are not, but there is a lot of that mentality out there still that men can do as they like, they can be shitty and and unkind and throw their privilege around, and women just have to take it. I know, I’ve been in the dating world these last six years and I’ve seen what’s out there. There’s a lot not to like. But I’ve also met some really wonderful men who are taking these dialogues seriously, who are examining themselves and their place in the world and adjusting accordingly. And of course there are, and have always been men, who have championed more equity in our societal constructs, in our systems, and even in relationships. Those are the men I write about, after all.

Can I manifest one of those, please?

August 5, 2021

On the Domestication of Humans

As a Sagittarius rising and a Myers-Briggs INFJ, I’m fascinated by the idea of discovering my true self, the person I was before the world changed me. In yoga we talk about this a lot. In fact that’s one of the many functions of yoga, to reunite you with your innermost self, your truest self (that is, in fact, what the word “yoga” means). In consequence, I’ve been giving a lot of thought to what it means when people respond to the parts of you they don’t like. That is, after all, why we fail to be our true selves, because we are ever and always trying to present to the world the parts of us—and only the parts of us—that are most palatable. We shove everything else aside and hide it in locked rooms inside our own psyches. Such is the source, at least according to some psychologists, of neuroses (see Marie-Louise von Franz’s The Problem of the Puer Aeternus).

It is often the case that I take the issues that conflict me the most and pour them into my novels. Doing so offers me the opportunity of placing the issue outside of my own mind where I can look at it and examine it in a little more detail—or at least from another perspective. I seem to be doing that now as I work tandemly on Guileless and Fearless. The first is about a young woman who is intent on challenging the limits of her own understanding. Growing up with four brothers, she is constantly aware of what it is she is missing out on in the way of education. At the same time that her father manages those limits, he also berates her for what she lacks. Her brothers think of her as silly and trivial and without a mind of her own. She has lots of opinions, that’s not the problem. Or maybe it is exactly the problem, for it’s the opinions they object to. Opinions without the facts to back them up, as we know, make up a great deal of the fodder of debates these days. But also, sometimes, it’s not what we do or don’t know that’s objectionable, but simply that we have opinions that challenge others. That there ought to be more than one voice in a marriage, more than one voice in a family or an institution, whether its religious or civic or commercial is something most of us would not debate. And yet … there are lots of people for whom the threat of losing the power of consensus feels extremely threatening.

In Fearless the heroin is not “accomplished” enough to please those who have stewardship over her future (or soon will have, at any rate), and yet she does have talents, we all do, but they are those that aren’t easily shown off in a ballroom or at a dinner party. She can play a little, sing a little, paint a little, sew a little, but she is a remarkable storyteller. Anciently, and even in today’s world, that’s a laudable skill, but at that time, it had no real use. It did not prepare her for marriage, did not prepare her to entertain, and offered nothing to the improvement of her domestic life. If she were a man, it might be a marketable skill, but a marketable quality in a woman was something to despise in the Victorian Era.

And what about now? There’s this huge, erupting conversation about what is acceptable for some people to do and not others. The hypocrisies, for instance, in what men can get away with (“he didn’t know what he was doing; he was drunk”, “boys will be boys”) versus what is acceptable in female behavior (“she had it coming”, “what did she think was going to happen if when she drinks/dresses like that?”) run rampant in our subconscious paradigms. While I find the disparity heartbreaking, I find the conversation (that we are having it) fascinating.

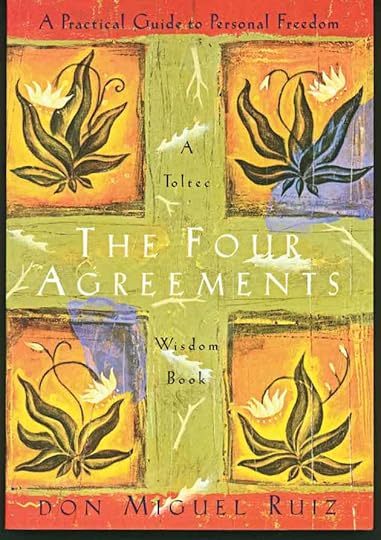

During my yoga teacher training, one of the books that was required reading was Don Miguel Ruiz’s The Four Agreements. Ruiz talks about domestication as the training we receive as children regarding how we are expected to interact with the world. We say “yes, please” and “no, thank you,” we sneeze into our elbows and cover our mouths when we yawn. We drive on the right side of the road, and we don’t take things that don’t belong to us. We use utensils when we eat (mostly) and refrain from kicking and hitting. And while all that is useful and even necessary, there are other things that are not

I’ve spent many years being indoctrinated with the idea that the reward for good behavior is the approval of others. Having been raised by an alcoholic father, I fall very firmly into the co-dependent category of human behavior and existence. I know how to be subtle. I know how to play small (despite the fact that I’m nearly 6′ tall). Religion was my friend because, as someone who is overly concerned with being a good person, I had this convenient checklist, and if I did all the things, that meant I was a-ok.

The problem comes when you finally take the mantel of responsibility upon yourself for trying to sort out who you are. Those who held the ropes and the rule books up to that point will have something to say when you threaten to step out of line. Those shame words and their accompanying narratives are used to put us back in place. Things like, “if you’re angry you’re not happy”, or “you’re being judgmental”, or “she’s gone off the deep end”. Think about it: Why do we have lawns? Why are houses only painted in solid colors and not in stripes or plaid? Why are some colors suitable for automobiles and not others. Why is it not o.k. to sing in public? Or to dance? Why are men supposed to have short hair and women never supposed to have tattoos?

Life is bizarre, and, truly, so many of the rules do not even make sense. But rules keep ups predictable, as do boxes and categories and judgments. We are all living in a state of fear, pretending we have it figured out when we don’t.

None of us has it figured out.

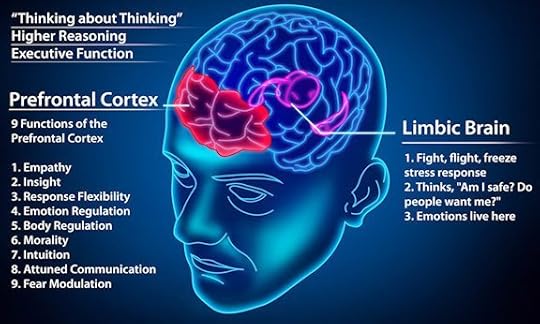

I was also taught that happiness looks a certain way, and if we are not happy, it’s a judgment upon our righteousness, on our worthiness, on the value of our existence. What’s interesting is that I’ve learned of the value of emotions and not just the “nice” ones. The value of anger, for instance, to inform you when a boundary has been crossed; the value of grief to help you get in touch with the well of emotion all around you (and the support and connection that brings); the value of fear to show us how to survive and to teach us how to value what is most precious. All of these emotions can be misused; of course they can, but the healthy expression of them is not something we should shame. But we do. Toxic positivity is real … and it’s unhealthy. Not only is it disrespectful of people who are struggling with depression, or loss, or any of a million other obstacle that may very well be no fault of their own, it invalidates the complexity of the human experience.

THERE ARE NO BAD EMOTIONS. Though there are certainly improper ways to act out on those emotions. Emotional intelligence is to everyone’s benefit. I think what the last few years has taught us is that too may people (particularly in the U.S. where the rate of trauma is so high) lack empathy. Sorrow, grief, and anger, are inconvenient emotions. It’s much easier to shame someone into the appearance of complaisance than to actually sit with them and help them sort out what it is they are feeling. Heck, we can scarcely sit sill with our own emotions! There are real problems in the world that are not going to get better by watching the news. That doesn’t mean we need to be upset by them, but we need to be willing to search inside for or own unique gifts and find the ways in which we can contribute. Neither is it realistic to expect that we are doing anything other than betraying ourselves when we sit by and smile and nod along when someone does something harmful or when our boundaries are betrayed. Such is the exact opposite of self-love.

I’m a passionate person, and while that’s not everyone’s cup of tea, I actually really like that about myself. It gives me the energy and motivation I need to write, to work for a purpose, to try to make the world a better place. It gives me the hope and courage to love, even after I have been disappointed and hurt. It is the joy in my existence, the energy that keeps me moving forward. It’s why, despite the difficulties and hardships of the last year, I have so much to live for and so much work to produce. And I have been.

I’m at a point in my life where I believe that the purpose of life is to heal from our traumas and find our true selves so that we can rise above hardship and offer our unique talents to make the world a better place. The more I’m allowed to express myself, the more I’m able to respect my own boundaries and maintain them, the more I am able to share who I am and who I am becoming with the world, the happier I am. But that journey does and should look different to everyone.

Blessings, and I’ll be back at the end of the month with some more fascinating research.

June 28, 2021

A Suitable Education for Girls

In an age when a woman’s greatest responsibility was to marry and bear children, education largely centered around the preparation for those roles. Working class women learned from their mothers or from other working class women how to ply their trades, with maybe some reading, writing, and maths thrown in, with focus on those skills that would allow them to supply for the necessities of the home.