David Barton's Blog

August 25, 2010

The pledge of Allegiance by David Barton

As previously noted, the Court's standard for what

constitutes an unconstitutional religious activity had grown increasingly more

narrow and restrictive from case to case; the Weisman case proved no exception.

In it, the Court introduced a new test for constitutionality: the

"psychological coercion test." Under this test, if a single individual finds

him uncomfortable in the presence of a religious practice in public, then that

activity is unconstitutional. The Court alleged that the unconstitutional

"psychological coercion" had occurred when the crowd stood for Rabbi

Gutterman's prayer:

What to most believers may seem nothing more than a

reasonable request that the nonbeliever respect their religious practices, in a

school context may appear to the nonbeliever or dissenter to be an attempt to

employ the machinery of the State to enforce a religious orthodoxy? The

undeniable fact is that the school district's supervision and control of a high

school graduation ceremony place public pressure, as well as peer pressure, on

attending students to stand as a group or, at least, maintain respectful

silence during the Invocation and Benediction. The dissent vehemently objected

to this new test:

As its instrument of destruction, the bulldozer of its

social engineering, the Court invents a boundless, and boundlessly manipulable,

test of psychological coercion. The opinion manifests that the Court itself has

not given careful consideration to its test of psychological coercion. For if

it had, how could it observe, with no hint of concern of disapproval, that

students stood for the pledge of Allegiance, which immediately preceded Rabbi

Gutterman's invocation? .

Since the Pledge of Allegiance included the phrase "under

God," recital of the Pledge would appear to raise the same Establishment Clause

issue as the invocation and benediction. If students were psychologically

coerced to remain standing during the invocation, they must also have been

psychologically coerced, moments before, to stand for and thereby, in the Court's

view, take part in or appear to take part in the Pledge.

August 18, 2010

The Kentucky Statute by David Barton

A carving of Moses holding the Ten Commandments, if that is

the only adornment on a courtroom wall, conveys an equivocal unclear and

uncertain message, perhaps a respect for Judaism, for religion in general, or

for law. It was striking that in Stone the Supreme Court completely ignored the

facts which led both the Kentucky legislature and the federal district court to

acknowledge the secular importance of the Ten Commandments. This unprecedented

rejection of fact by the Court drew sharp criticism from Justice Rehnquist in

his dissent:

The Court concludes that the Kentucky statute involved in

this case "has no secular legislative purpose," and that "the preeminent purpose

for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in

nature." This even though, as the trial court found, "the General Assembly

thought the statute had a secular legislative purpose and specifically said

so." The Court's summary rejection of a secular purpose articulated by the

legislature and confirmed by the State court is without precedent in

Establishment Clause jurisprudence. This Court regularly looks to legislative

articulations of a statute's purpose in Establishment Clause cases. The Court

rejects the secular purpose articulated by the State because the Decalogue is

"undeniably a sacred text." It is equally undeniable, however, as the elected

representatives of Kentucky determined, that the Ten Commandments have had a

significant impact on the development of secular legal codes of the Western

World. The trial court also concluded that evidence submitted substantiated

this determination.

Certainly the State was permitted to conclude that a

document with such secular significance should be placed before its students,

with an appropriate statement of the document's secular import. Almost as

amazing as the Court's claim that the Ten Commandments lacked secular purpose

was the Court's complaint of what would occur if students were to view the

Commandments:

If the posted copies of the Ten Commandments are to have

any effect at all, it will be to induce the schoolchildren to read, meditate upon,

perhaps to venerate and obey, the Commandments. The Court therefore concluded:

This is not a permissible state objective under the

Establishment Clause. The mere posting of the copies the Establishment Clause

prohibits. The Founding Fathers would have disagreed vehemently.

August 17, 2010

The Alabama State legislature by David Barton

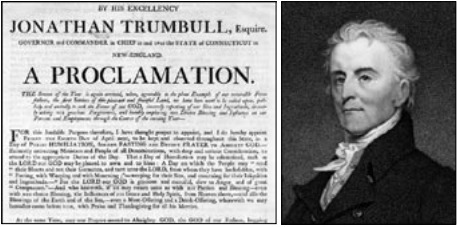

The Alabama State legislature had simply permitted a

voluntary, silent activity; the Court concluded that this was the equivalent of

encouraging a religious activity and was thus an impermissible establishment of

religion. Ironically, Alabama came under the provisions of the U. S.

territorial ordinance which had declared that:

Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to

good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education

shall forever be encouraged. The Founders thought it proper for the government

to promote religious activities. In fact, they frequently encouraged such activities.

For example emphasis added in each quote:

Sensible of the importance of Christian piety and virtue

to the order and happiness of a state, I cannot but earnestly commend to you

every measure for their support and encouragement. The very existence of the

republics depends much upon the public institutions of religion. John Hancock

A free government can only be happy when the public

principle and opinions are properly directed by religion and education. It

should therefore be among the first objects of those who wish well to the

national prosperity to encourage and support the principles of religion and

morality. Abraham Baldwin, Signer of the Constitution

The promulgation of the great doctrines of religion, the

being, and attributes, and providence of one Almighty God; the responsibility to

Him for all our actions, founded upon moral accountability; a future state of

rewards and punishments; the cultivation of all the personal, social, and

benevolent virtues; these never can be a matter of indifference in any

well-ordered community. It is indeed difficult to conceive how any civilized

society can well exist without them. Joseph Story, U.S. Supreme Court Justice;

Father of American Jurisprudence

To promote true religion is the best and most effectual

way of making a virtuous and regular people. Love to God and love to man is the

substance of religion; when these prevail, civil laws will have little to do.

The magistrate or ruling part of any society ought to encourage piety and make

it an object of public esteem.

August 9, 2010

The constitutional wall of separation by David Barton

One further note from this decision: a concurring Justice

observed that, through this ruling, the Court was now assuming "the role of a

super board of education for every school district in the nation" an ominous

prediction of what has now become the norm. Engel v. Vitale, 1962

For fourteen years following the McCollum case, the Court

not only ceased to strike down voluntary religious activities for students, it

actually upheld them, retreating significantly from its inflexible concept of

"separation" introduced in 1947 in Everson see Zorach v. Clauson, 1952 21.

However, in the Engel case, the Court reverted to its Everson position; it

attacked the long-standing tradition of school prayer and struck down this

simple 22-word prayer from New York schools:

Almighty God, we acknowledge our dependence upon Thee, and

we beg Thy blessings upon us, our parents, our teachers and our Country.

Contemporary reviewers often claim that the "real" issue in this prayer case

was coercion since it involved a state approved prayer. Yet this is a misportrayal;

there was no coercion; even the Court conceded that the schools did not compel

any pupil to join in the prayer over his or her parents' objection.

New York had taken great pains to provide that

participation in these prayers be completely voluntary. Furthermore, in an

attempt to be as inoffensive as possible, the prayer's wording was simply a

nonsectarian acknowledgment of God. In fact, that acknowledgment was so bland

that a later court described it "as a 'to-whom-it-may-concern' prayer." Since

the prayer was both voluntary and nondenominational, it should have been

upheld; yet the Court explained why it must be struck down: Neither the fact

that the prayer may be denominationally neutral nor the fact that its

observance on the part of the students is voluntary can serve to free it from

the limitations of the Establishment Clause, as it might from the Free Exercise

Clause, of the First Amendment. It ignores the essential nature of the

program's constitutional defects. Prayer in its public school system breaches

the constitutional wall of separation between Church and State.

August 2, 2010

The Divine Spirit by David Barton

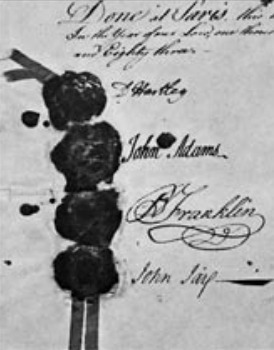

And as my children will have frequent occasion of

perusing this instrument and may probably be particularly impressed with the

last words of their father, I think it proper here not only to subscribe to the

entire belief of the great and leading doctrines of the Christian religion,

such as the being of God, the universal defection and depravity of human nature,

the divinity of the person and the completeness of the redemption purchased by

the blessed Savior, the necessity of the operations of the Divine Spirit; of

Divine faith accompanied with an habitual virtuous life, and the universality

of the Divine Providence: but also, in the bowels of a father's affection, to

exhort and charge them that the fear of God is the beginning of wisdom, that

the way of life held up in the Christian system is calculated for the most

complete happiness that can be enjoyed in this mortal state. Richard Stockton,

Signer of the Declaration

These wills, and others like them, represent the tone of

what was common among the Founders. Additionally, the personal writings of many

other Founders reflect equally succinct declarations about their faith in

Christ. Consider a few examples:

My hopes of a future life are all founded upon the Gospel

of Christ and I cannot cavil or quibble away evade or object to the whole tenor

of His conduct by which He sometimes positively asserted and at others

countenances permits His disciples in asserting that He was God. John Quincy

Adams

Now to the triune God, The Father, the Son, and the Holy

Ghost, be ascribed all honor and dominion, forevermore Amen. Gunning Bedford,

Signer of the Constitution

The religion I have is to love and fear God, believe in

Jesus Christ, do all the good to my neighbor, and myself that I can, do as

little harm as I can help, and trust on God's mercy for the rest. Daniel Boone,

Revolutionary Officer; Legislator

July 29, 2010

The Religious Nature of the Founding Fathers by David Barton

If the Founders were generally men of faith, then it is

illogical to believe that they would establish public policies either to

prohibit or to inhibit expressions of the faith they cherished. On the other

hand, if the contemporary portrayal is correct, and if as many now claims the

Founders were by and large a collective group of atheists, agnostics, and

deists, then it is logical that they would not want religious activities as a

part of official public life. Therefore, a vital question to be answered in the

current debate over the historical and constitutional role of public religious

expressions is, "What was the overall religious disposition of the Founding

Fathers?"

Before delving into an investigation of their religious

nature, it is important first to establish what constitutes a "Founding

Father." As previously noted in the preface, for the purpose of this work, a

"Founding Father" is one who exerted significant influence in, provided

prominent leadership for, or had a substantial impact upon the birth,

development, and establishment of America as an independent, self-governing

nation. This obviously includes the fifty-six signers of the Declaration of

Independence, as well as the fourteen different Presidents who governed America

from 1774 to 1789. Under America's unicameral system prior to the Constitution,

the President of the Continental Congress essentially served as the President

of America.

Additionally, the handful of significant military leaders

who provided leadership for, fought for, and secured our independence must be

included. In other words, without the work of the fifty-six men who signed the

Declaration, the fourteen Presidents of America who led the Continental

Congress, or the three-dozen or so prominent military leaders, America as we

know it undoubtedly would not exist today.

Included next are the fifty-five men at the

Constitutional Convention as well as the major leaders responsible for the

ratification of the Constitution on many occasions, these were the State

Governors without whose efforts there would have been no United States of

America. Therefore, without the work of the delegates at the Constitutional

Convention and the leaders of the ratification movement, America would not have

the form of government it has now enjoyed for over two centuries.

July 22, 2010

Courage and Patriotism by David Barton

Historian Daniel Dorchester reported numerous other

similar incidents: Of Rev. John Craighead it is said that "he fought and

preached alternately." Rev. Dr. Cooper was captain of a military company. Rev.

John Blair Smith, president of Hampden-Sidney College, was captain of a company

that rallied to support the retreating Americans after the battle of Cowpens.

Rev. James Hall commanded a company that armed against Cornwallis. Rev. Wm.

Graham rallied his own neighbors to dispute the passage

of Rockfish Gap with Tarleton and his Britain dragoons. Rev. Dr. Ashbel Green

was an orderly sergeant. Rev. Dr. Moses Hodge served in the army of the

Revolution. In fact, so prominent were the clergy in the struggle that the

British called them the "Black Regiment" 117 due to the black clerical robes

they wore. On May 2, 1778, when the Continental Army was beginning to emerge

from its infamous winter at Valley Forge, Commander-in-Chief George Washington

commended his troops for their courage and patriotism and then reminded them

that: While we are zealously performing the duties of good citizens and

soldiers, we certainly ought not to be inattentive to the higher duties of religion.

To the distinguished character of Patriot, it should be

our highest glory to add the more distinguished character of Christian. Later

that year, still in the midst of the Revolution, the help that America had

already received from their "firm reliance on Divine Providence" was so obvious

that George Washington told General Thomas Nelson: The hand of Providence has

been so conspicuous in all this that he must be worse than an infidel that

lacks faith, and more than wicked, that has not gratitude enough to acknowledge

his obligations. The exploits of many of these clergy-patriots are recorded in

several older historical works, including The Pulpit of the American Revolution

– 1860; Chaplains and Clergy of the Revolution – 1861; and The Patriot Preachers

of the American Revolution – 1860.

On October 12, 1778,

Congress again reaffirmed the importance of religion and made provision for its

widespread encouragement when it issued the following act: Whereas true

religion and good morals are the only solid foundations of public liberty and

happiness: Resolved, That it be, and it is hereby earnestly recommended to the

several States to take the most effectual measures for the encouragement

thereof.

July 15, 2010

The American Founding Fathers by David Barton

By George Washington's own words, what youths learned in

America's schools "above all" was "the religion of Jesus Christ." The American Revolution

and the Acts of the Continental Congress The seeds of separation between

America and Great Britain had been sown as early as 1765 when Great Britain

began to impose on the Colonies a number of tyrannical and, what the Colonists

called, unlawful or "Intolerable Acts." Although the Americans faithfully

sought redress from these arbitrary and often capricious policies, the response

from the Crown was frequently hard fisted. The fact that British troops had

even fired on their own citizen's in the 1770 "Boston Massacre" further

deepened the rift.

As a result, some individuals understandably began to

incite open insurrection; however, America's patriot leaders remained firmly

committed both to lawful procedure and to a peaceful resolution of their differences

with Great Britain. Some today contend that the American Revolution represented

a complete violation of basic Biblical principles. They argue from Romans that

since government is of God, then all government decrees are to be obeyed as

proceeding from God. Interestingly, it was this same theological argument which

had resulted in the "Divine Right of Kings" philosophy which reasoned that

since the King was divinely chosen by God, therefore God expected all citizens

to obey the King in all cases; anything less, they reasoned, was rebellion

against God.

The American Founding Fathers strenuously disagreed with

this theological interpretation. For example, Founding Father James Otis a

leader of the Sons of Liberty and the mentor of Samuel Adams openly struck

against the "Divine Right of Kings" theology. In a 1766 work he argued that the

only king who had any Divine right was God Himself; beyond that, God had

ordained that the power was to rest with the people: Has it government any

solid foundation? Any chief cornerstone? I think it has an everlasting

foundation in the unchangeable will of God, the Author of Nature whose laws

never vary. Government is by no means an arbitrary thing depending merely on

compact or human will for its existence.

The power of God

Almighty is the only power that can properly and strictly be called supreme and

absolute. In the order of nature immediately under Him comes the power of a

simple democracy or the power of the whole over the whole. God is the only

monarch in the universe who has a clear and indisputable right to absolute

power because He is the only one who is omniscient as well as omnipotent. The

sum of my argument is that civil government is of God, that the administrators

of it were originally the whole people.

July 9, 2010

The Sabbath in the New Testament by David Barton

Even Jefferson and Madison, touted by today's liberal

groups as champions of tolerance, strongly opposed anything except monogamous

heterosexual relationships. This is established by the fact that they enacted

the death penalty for bigamy and polygamy and that Jefferson himself proposed

"castration" as the penalty for sodomy.

Although the argument has been raised for generations

that any moral behavior or belief should be protected by the Constitution an

argument which has always been consistently denied and refuted by responsible

courts the difference is that today's courts seem determined to sustain it.

City Council of Charleston v. S. A. Benjamin, 1846 Supreme Court of South

Carolina At issue in the following cases were violations of what today are

called "Blue Laws," or Sunday closing laws.

The question often surrounding such laws was whether they

were a specific legislation of Christianity to the exclusion of all other

beliefs. Many courts believed that this was not necessarily so; they pointed

out, first, that no particular day had been established by God's decree as the

Sabbath in the New Testament, and second, that the Apostles themselves allowed

great latitude on this issue. Consequently, these courts held that while Blue

Laws were generally associated with religion, they were not necessarily

religious mandates. Further, since days of rest had been proved to have clear

secular benefits on both public health and morale, these courts.

Following the French Revolution 1789, France made a

calendar change so that workers were allowed one day rest in ten rather than

the traditional religiously based one in seven. See, for example, Noah Webster,

The Revolution in France Considered in Respect to Its Progress and Effects New

York: George Bunce, 1794, p. 20. Apparently, the result on the workers' health

and morale was so detrimental that the one day rest in seven was reinstituted.

ruled that such laws fell within the State's legislative prerogative as the U.

S. Constitution had phrased it to "promote the general welfare" of its

citizens.

For example emphasis

added in each example: The legislature of the State has the power, under the

Constitution, to prohibit work on Sunday as a matter pertaining to the civil wellbeing

of the community. Melvin V. Easley It a day of rest enables the industrious

workman to pursue his occupation in the ensuing week with health and

cheerfulness without it; he would be worn out and defaced by an unremitted

continuance of labor. Johnston V. Commonwealth.

July 2, 2010

The Judicial Evidence by David Barton

It seems logical that if this had been the intent of the

Founding Fathers for the First Amendment as is so frequently asserted then at

least one of those ninety would have mentioned that phrase; none did. Since the

"separation" phrase was used so infrequently by the Founders, and since early

courts rarely invoked it, how did those courts rule on the religious issues and

activities which confront today's courts? Were their conclusions different from

those reached now? As demonstrated in the following chapter, the answer is an

emphatic and a resounding, "Yes!"

Excerpts from twentyone early cases will be presented in

this chapter. These cases, representative of many others, will demonstrate that

contrary to the actions of current courts, early courts protected, advanced,

encouraged, and promoted the role and influence of religion throughout society.

Significantly, several Judges who ruled in these early cases had personally participated

in the drafting and ratification of the Constitution and thus were quite sure

about its intent.

Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 1892 United

States Supreme Court This case provides a good starting point since it

incorporates several previous decisions. At issue was an 1885 federal

immigration law which declared: It shall be unlawful for any person, company,

partnership, or corporation, in any manner whatsoever to in any way assist or encourage

the importation of any alien or foreigners into the United States under

contract or agreement to perform labor or service of any kind.

Since this law, on its face, appeared to be a straightforward

ban on hiring foreign labor, when the Church of the Holy Trinity in New York

employed a clergyman from England as its pastor, the U. S. Attorney's office

brought suit against the church. When the case reached the Supreme Court, the Court

began by examining the legislative records surrounding the passage of that law

and discovered that its sole purpose had been to halt the influx of almost

slavelike foreign labor to construct the western railroads. Thus, while the

church's hiring of the minister had violated the wording of the law, it clearly

had fallen far outside the spirit and intent of that law.

David Barton's Blog

- David Barton's profile

- 256 followers