Alex Bledsoe's Blog

June 18, 2025

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

September 6, 2022

A Curated List of Exorcism Movies

There are more movies about exorcisms that any one person could ever possibly see; I know, because I’ve watched a lot of them during the years I worked on my upcoming novel Dandelion (pre-order here). This is a modern genre, too; it started in 1973, with the release of the grandaddy of them all, The Exorcist, so there are no vintage black-and-white true exorcism films from Universal or Hammer. In fact, most exorcism films are trashy low-budget affairs. Everything that makes The Exorcist a classic—great performances, realistic special effects, a pace that gives time for subtlety and meaning, unforgettable music—is ignored in favor of blood, guts, cliches and paper-thin characters.

But in that wilderness of manure, I did stumble across some daisies. Keep in mind, these are all my opinions; your mileage may vary. But if you’re intrigued by exorcisms, I think you’ll find these five films pretty interesting.

The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005)

This is basically a courtroom drama dressed up as a horror film. It’s inspired by the case of Anneliese Michel, who died as a result of her exorcism in 1976. In this film, Emily Rose dies at the beginning, and through the trial of the priest accused in her death, we learn that every supposed sign of “possession” can be explained by some non-supernatural clause. My favorite exchange comes when the prosecutor, played by Campbell Scott, objects to the testimony of Dr. Adani, a defense expert in primitive religions who claims possession is real:

Prosecutor: Objection.

Judge: On what grounds?

Prosecutor: How about silliness, Your Honor?

This might be the most balanced horror film you’ll ever see, and at the end you’re left to make up your own mind if Emily Rose was really possessed.

Exorcismus (2010)

Good British horror films are known for their subtlety. Watch the classics like Night (aka Curse) of the Demon, Burn, Witch, Burn! (aka Night of the Eagle), or The Wicker Man and you’ll see what I mean. Exorcismus applies that restraint to the possession genre. All of the tropes are here, but they’re restrained and understated: for example, the possessed girl does levitate, but only about a foot off the floor. The emotional toll of possession on the bystanders is given room here as well, something that’s often overlooked.

Requiem (2006)

This isn’t really an exorcism film, because the girl’s not really possessed. But it’s included here because it’s a dramatization of the death of Anneliese Michel, the same case that inspired The Exorcism of Emily Rose, only Requiem attempts to depict what might have actually happened. It’s a sad film because the protagonist is a victim of religion and ignorance, not the devil, and since it’s based on a famous case, the ending isn’t a surprise. But it’s very well made, and makes a nice contrast to the more garish films on this list.

Ava’s Possessions (2015)

There are about three too many ideas in this low-budget gem, but it’s rare to see a movie with too much on its mind. It comes at the traditional possession narrative from a singular perspective: what happens after the exorcism? In this case, support groups, awkward family dinners, and people whose motives can’t be trusted. Played mostly for laughs, its reach exceeds its grasp, but there’s still a lot of great stuff.

Abby (1974)

The inevitable “Black Exorcist” film, made at the height of Blaxploitation, stars Blacula himself, William Marshall, as the exorcist. But this is no mere Jess Franco-style ripoff. Because she’s the demure wife of a minister, Abby’s possession takes an unabashedly sexual turn, and the change from supportive spouse to taunting emasculator is fascinating. As an added bonus, it takes place during the super-funky Seventies, with all the accompanying fashion, decor, and music. This one is super-hard to find, since Warner Brothers successfully had it pulled for alleged copyright infringement of The Exorcist. Hopefully someone will wrangle the rights and give us a decent restoration. (You might find it on Youtube, but I’m only linking to the trailer.)

And if you have any favorites, please tell me about them in the comments!

August 29, 2022

Religion and racism: two things that help create evil in my novel Dandelion.

Of my thirteen prior novels, eight of them were set in the American South. It’s where I grew up and lived for the first forty years of my life, from Tennessee down to the Gulf Coast. It’s a place I know better than any other. And because of that, I believe that it’s impossible to write about the south in any genre, including horror like my upcoming novel DANDELION, without dealing with two things: race, and religion.

Religion? That’s easy. The region has always been known as the Bible Belt, not so much for its devoutness, but for its insistence on appearing devout. The largest denomination, Southern Baptist, is rife with hypocrisy and sex-related misdeeds, as highlighted in recent news stories. The smaller ones are often fiefdoms run by iron-fisted despots. And most of them have no trouble endorsing (failed) Georgia gubernatorial candidate Kandiss Taylor’s campaign slogan of “Jesus, Guns, Babies.”

Are there sincere Christians? Yes, of course. I’ve been fortunate enough to know a few who truly tried to walk with Christ. But they’re rare as the proverbial hen’s teeth or frog’s hair. Most see their Christianity as a shield to hide their racism, misogyny and homophobia, and if that sounds harsh, well, ask other people who’ve grown up with it.

In my novel Dandelion, religion is real. There is a God. Demons exist. And there are religious people both sincere and phony. I’ve tried to recreate the feeling of various manifestations of religion, so that the reader gets a sense of what it’s like in those small churches and revival tents.

And as for racism…

[image error]That the south is racist is not new, or news. When I was growing up, it was just as racist as it is today, but there was at least a sense of shame about it. One woman I worked with swore that Black people met in their churches to discuss ways to make work more difficult for white people, but she only spoke about it in low, secretive tones. I had an aunt who unrepentantly named her black dog the “n” word, but they lived in the country and would never bring the dog into town. And my family’s church was outraged when our new pastor invited a black family to attend services, but they insisted it wasn’t racism, just the lack of consideration for the congregation’s “old-timers.” Nowadays, when racism and racists are right out there on the lawns, pickup trucks, and social media, none of these things are hidden.

So in Dandelion, racism, like religion, is real, and some characters are blatant racists. And their racism is not defended or glorified but rather depicted, in all its horror and vileness, as realistically as possible. Some readers may assume that if a white author depicts racism, it means the author condones it, but that’s not the case. I lived in these places, with these people, and if you’ll notice, the characters espousing these views are the bad guys.

So even though Dandelion is a horror novel, with all the violence, sex, and spooky shit that the genre demands (and that, quite frankly, is part of the fun of writing it), it’s set against a social background that’s as real as I can make it. And that’s where the true evil grows.

Preorder Dandelion before its release here. It hits stores and devices October 1. Perfect for those Halloween stockings! (Not a thing? Should be a thing.)

August 22, 2022

The origins of Dandelion, part 2

Read part 1 here, and a sidebar post on the music of Exorcist II: The Heretic here.

In a Washington Post story about J.D. Vance’s run for office, I first encountered the term ruin porn. lf you’ve read his memoir Hillbilly Elegy, you’ll know what the term means: a tour through ruined rural America, where everything that once thrived is gone, and the people left are mired in unemployment, addiction, and crime. It’s both insulting and accurate, and it makes Vance both the herald of this new rural America, and another of the vampires feeding off it.

I like to say I grew up in a small Tennessee town of 350 people, 250 of whom were related to me. If nothing else, that limits your dating options…or should. But the speed trap/wide spot in the road I called home, Gibson, was equidistant between two other towns, Humboldt and Milan, and I grew familiar with both since Gibson lacked essentials like a grocery store, school, or doctors. Or much of anything else.

I left Gibson when I went to college, and over the decades my visits became fewer and fewer, until my mother’s growing infirmities meant I had to return to take over certain things she could no longer manage. I found myself, as you do, rerunning the old back roads and finding that most of the landmarks I recalled were long gone.

But not all of them.

[image error]Both Humboldt and Milan had Walmarts as far back as I can remember as well. This was the original Walmart, a small but useful store that blended into the retail landscape and allowed other businesses to breathe. We shopped there, but we also shopped at grocery stores, drug stores, hardware stores, auto parts stores, a whole thriving small-town economy.

After I left, though—and to hear my late stepfather tell it, after the death of founder Sam Walton—Walmart changed into the all-consuming monster we know today. With the advent of the 24-hour “super-store,” where shoppers could buy everything at cheaper prices any time of day or night, all those other businesses died. Along with them went the jobs they created, and the pride of those owners and workers. Many no doubt ended up working for Walmart, “feeding the beast that killed them,” as a character put it on King of the Hill.

As a result, these towns became zombies of their former selves. Abandoned and empty houses filled up once-vibrant neighborhoods, pawn shops and antique (i.e., junk) stores sprang up in what were once downtown businesses, and check-cashing operations made their fortunes off the community’s desperation. There were attempts at rejuvenation, but they were spotty and ultimately helped only a small part of the community.

[image error]This isn’t just hearsay. I saw it. And it stuck with me for years.

I knew I wanted to write about this, but I’m no Upton Sinclair; social treatises disguised as novels don’t interest me. I mean, honestly, who would want to read that? So it sat in my head until it finally connected with another subject I’d always wanted to write about, demonic possession. Because one day, it hit me: what if, instead of being just an economic hell mouth, a big box store was a literal one, a place where demons congregated to await the chance to possess their victims?

It’s a silly idea on the surface, I suppose. After all, no business is inherently evil, and many people would not be able to afford essentials if it wasn’t for Walmart, Target, et. al. But when you see the destruction wrought by big boxes’ appeal to cheapness at all costs (and the simultaneous appeal to people’s basest instincts), it’s hard not to feel that it’s somehow responsible.

And in my novel Dandelion, it most definitely is.

August 17, 2022

Sidebar: Ennio Morricone, Magic, and Ecstasy

This is an addendum to my earlier blog about Exorcist II: The Heretic.

One of the best things about that unholy mess of a movie is the score by Italian maestro Ennio Morricone. And one of the best things about his score is the track “Magic and Ecstasy,” used mainly in the trailer I posted in my last blog. But here it is in its full glory:

What surprised me more than anything, when I did a little digging, was how many times this tune has been covered. The best known one is by the late Philip Charles Lithman, who performed as Snakefinger (sorry, YouTube won’t let you watch it here):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZFuKZIBjyHA

And here’s a version by the Italian death-metal band Omicidio, another one that YouTube won’t let me embed:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KQj80_cHZ14

Not sick of it yet? Here’s a cover by New Jersey guitarist Leon Muhudinov that (you guessed it) YouTube won’t let me share:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZUKzueAL0p8

But finally, here are some that are freed from YouTube’s deathly grasp! Wondering if it can be performed live? Here’s Nilbog, a horror film score tribute band, to prove it:

Here’s an atonal, cacophonous version by Edible Woman:

And here’s an almost punk cover by The Zag Men (now the Pine Box Boys):

And finally, what would a list like this be if it didn’t include one with a dog doing the vocals? Here’s David Furtado featuring Sasha:

There might be more out there that I just haven’t run across. And I find it astounding that something from what is generally regarded as the worst sequel of all time could inspire such a rich, almost underground life. It illustrates something that I’ve come to believe more and more: every work of art, however objectively “good” or “bad,” can inspire someone somewhere.

Stay tuned for more on the origin of my horror novel Dandelion, out October 1 from Falstaff Books. Pre-order from Amazon here, or support your local independent bookstore by pre-ordering from them!

August 15, 2022

The origins of Dandelion, part 1

In the summer of 1977, I saw a movie that would change my life.

No, not that one. I mean, yes, I saw Star Wars multiple times, and my first published byline was a review of it that I wrote for a small-town paper. But I’m referring instead to Exorcist II: The Heretic.

[image error]I was 14 that year, spending the summer with my sister’s family in Missouri. My sister was 16 years older than me, so I was left to my own devices most of the time. And once I discovered the two teenage girls who lived right across the street, you can imagine where those devices led me.

But i had already developed a love of film, even though my critical faculties were still a work in progress. I knew that The Exorcist had been a huge deal, one that I hadn’t seen (I was only ten the year it came out, and this was long before any sort of home video). But the commercials made the sequel look amazing (the trailer, on YouTube, is genuinely cool). I begged my brother-in-law to take me, since I’d never been to an R-rated movie before (and did not realize that, as Alan Spencer says, the R rating is designed to “keep out those under 18 without money”). And I worked up the nerve to invite one of those teenage girls, Gina, to go with us. She had no interest in the movie, or me; I think she went just to get out of the house.

The movie was, shall I say…unexpected.

Since I’d never seen The Exorcist, I had nothing to compare this to, but the gore was minimal, the scares were nonexistent, and the overall effect was . . . odd. Several scenes prominently featured teenage Linda Blair’s jiggling breasts, which didn’t seem as creepy to me then as it does now. I genuinely didn’t know what to make of it. Access to reviews wasn’t as easy then (you had to get the magazines or newspapers day and date, or you were out of luck) so I had nothing to guide me. Yet there was something about it that stuck with me.

I read the making-of paperback, and wish I’d held onto it since it’s out of print now and sells for a small fortune. I bought the soundtrack, which became my introduction to Ennio Morricone. I wanted to read the novelization, but there wasn’t one. No one else I knew saw it, save for my brother-in-law, who gave it this backhanded review: “It was a very well-made movie.”

[image error]And that was it for the next few years. I didn’t see it again until the home video boom of the 80s, when I watched it on VHS and discovered that my initial WTF was, in fact, the right response. Because by any conventional standards, Exorcist II: The Heretic is a hot mess.

And yet . . .

I can’t claim it’s an undiscovered gem, because it’s been watched and written about pretty much since it opened, and the critical consensus has barely wavered. Yes, visually it’s excellent, the music is great, and the ideas are truly ahead of their time. But against that, you have some of the most wooden acting you’ll ever see; imagine if Keanu Reeves played every role, even the sixteen-year-old Regan, and you’ll get some idea. And the cast were not B-string slackers: Richard Burton, Louise Fletcher, cameos by James Earl Jones and Ned Beatty. If you can’t pull performances out of them, the problem isn’t with the cast, it’s with the director, in this case John Boorman.

Which is not to say Boorman is a hack. He’s made at least two acknowledged classics, Deliverance and Excalibur, along with Point Blank, Hope and Glory, and The Emerald Forest. But he also made Zardoz, a quintessential WTF movie, and that seems to be the Boorman who showed up for Exorcist II. As a result, it has gone down in history as possibly the worst sequel ever.

Still, over the years I kept returning to it. Part of it was nostalgia, but part of it was an aspect of the story that somehow got missed among all the production design. The story of a teenage girl who’d once been possessed having to go through it again was, in fact, a great idea. The idea of a cleric who wanted to help and had to parse out the truth was a tremendous character concept. They were, in fact, wasted in Exorcist II: The Heretic.

So I decided that maybe I should pick them up, shake them off, dip them in batter and deep fry them.

And that is first part of the origin of my new horror novel, Dandelion. Stay tuned for the part that involves big-box stores.

August 7, 2022

So, like…where have I been?

So some of you might wonder why it’s been four years, since 2018’s The Fairies of Sadieville, since I’ve had a new novel out. What could I have been doing?

There’s a few answers to that. In the summer of 2018, I lost both my mother and my ten-year-old son. The double-whammy of losing both my past and future within three months was a blow that knocked me sideways in more ways than one, and as you can imagine, it took a while for me to get back on course. I’m not ashamed to say I saw a therapist, as did we all, and eventually got myself pointed back in the right direction.

Career-wise, when I finished the Tufa series, I was as a crossroads. As I’ve learned the hard way, my best work comes from writing the whole novel, not three chapters and a synopsis, or three chapters and a pitch, or a pitch based on an outline. But I tried all these, and they were all rejected because whatever talent I have doesn’t come out in those forms. It comes out in the final manuscripts.

I also know that to make something my best, I need to finish it and put it away for awhile so I can come back to it fresh for revisions. When I try to work straight through, I lose the perspective that’s so necessary to my polishing process. I worked for months on a horror novel (not Dandelion) that kept going off the rails, only I was so close to it (and so desperate to see something else in print) that I couldn’t grasp how wrong it had gone. That manuscript is currently in the “burn after death” pile, because it really is that bad, although the setting may resurface in another project one day.

Through all this, the publishing industry changed as well, and that forced a reset of my expectations for my career. Put bluntly, to the Powers That Be I’d had my shot at becoming a bestseller and hadn’t done so. As they say, writing is an art but publishing is a business, and that’s never been more true than right now, as reading plummets and publishers merge. So I had to address my career in new ways.

One of these new ways to return to horror, something I hadn’t written since my vampire novels Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood. I landed on an idea I’d nursed for a long time, and which I’ll describe in more detail in coming posts. My other approach was to put stories in themed anthologies (and many thanks to the good folks at Zombies Needs Brains and West Street Publishing), as well as do some non-fiction writing about science fiction and horror films (thanks to Prof. Christopher McGlothlin at Ghost Show Press). These let me keep my hand in as I readied my next novel.

So I owe my new agent Paul Stevens, and my new publisher John Hartness at Falstaff Books, for having faith in what I still had to offer. And because of them, you’ll be reading about how my novel Dandelion, out October 1, 2022, came about.

July 20, 2021

Raney and the road not taken

****Trigger warning for racism.****

I’ve had one legitimately wealthy relative: for the sake of this, we’ll call her Aunt A. She was my godmother, and since she never had any children of her own, she a) saw me as a substitute, and b) had no idea how to relate to a child. She’s the reason I hate squash to this day, after she made me sit at the table for three hours until I ate it. Believe me, room-temperature cooked squash will convert no one.

She also ruined my enjoyment of art by insisting I draw things I didn’t want to draw, in order to learn to draw correctly. I didn’t care if my Flintstones or Batman drawings were “correct,” I cared if they were cool. But “cool” was not a valid standard. So when I started writing, I kept it hidden for as long as I could, well into adulthood.

When Aunt A found out I was a writer, she insisted I let her read something. At the time, I was deep into my Firefly Witch series of stories, which were definitely not her cup of sweet tea. She was appalled by the violence and occasional sex, but what really offended her was female characters cursing. In her genteel world, women just didn’t talk like that.

As an example of the kind of writing a proper young man should attempt, in 1995 or so she gave me a novel by North Carolina’s Clyde Edgerton called Raney. I hadn’t thought about this book in years, but on a recent trip to North Carolina, I spotted a worn paperback at a thrift store and showed it to my wife.

“This is how my Aunt A thought I should write.”

She looked it over and said, “I want to read it.” Which she did, very quickly, because it’s a short book.

“What did you think?” I asked when she was done.

“It’s…pretty racist.”

My own memory of reading it had long since faded. “Really?”

“Oh, yeah.”

So I reread it myself. And boy, she wasn’t kidding.

The front cover tells us:

[image error]As the back text says:

[image error]And by “everyone,” they must mean racists. Because that’s who the book’s about, and I’m pretty sure who it’s for.

Let me back up a little. I truly believe that if you write about the south and don’t acknowledge racism, you’re being dishonest. I’ve written eight novels set in the south, and racism is one of the threads that runs through them, because it runs through the real place. But I never condone it, or treat it as less than awful.

For reasons that will become clear, I’ve never read another book by Mr. Edgerton, so I can’t speak to them. But it’s clear that in Raney, he sees racism as just another harmless quirk that readers should look on with amusement. It’s the same racism I grew up with in my family, which I used to excuse as “benign” because it wished no active harm on anyone, it just felt liked they’d be happier with their own kind. Thankfully I outgrew that (education will do that to you), but it’s definitely how my family still feels, and most definitely how Aunt V (who worked many years as a fundraiser for various Confederate memorial causes) viewed the world.

Lest you think I exaggerate about Raney, here are some examples.

Raney and her family, good Baptists who go to church every Sunday, use the “n” word with abandon in casual conversation. The book, written in Raney’s voice, makes Charles the foolish one for objecting to it. She even says,

Charles has this thing about n******. For some reason he don’t understand how they are.

(And in case you wondered, there are no asterisks in the actual text.)

Raney’s family firmly believes in segregation, and Raney even confuses the words “integration” and “segregation” in conversation (in the context of the book, this is considered “humor”). Raney’s Aunt Naomi, complaining about blacks using the traditionally “white” part of the beach, says:

“It’s just that they need to stay in their own place at their own beach just like the white people stay at their own place at their own beach.”

Nobody said anything…but you could tell we all agreed except Charles. He walks through the screen door on outside.

“I don’t understand where he gets some of his attitudes,” says Aunt Naomi.

And at the end of chapter three, regarding Johnny Dobbs, a black Army buddy of her husband, Raney says:

…but if he is a n*****, he can’t stay here. It won’t work. The Ramada, maybe. But not here.

This is actually the set up for a joke, and the punchline comes at the very end of the book in the birth announcement of Raney and Charles’s first child:

Mr. Johnny Dobbs, from New Orleans, was named godfather and is visiting for a few days. He is staying at the Ramada Inn.

Sure, this was in the Nineties. And the book was published ten years earlier, in 1985. It was, as they say, a different time. But I definitely knew this was icky when I read it, and I’m betting plenty of other people did when it first came out. Much like Steel Magnolias, this is an all-white version of the south where black characters (such as the above-mentioned Johnny Dobbs) are either totally absent, or mentioned but never allowed to speak for themselves.

So this is what my Aunt A thought was the acceptable southern literature she wanted me to emulate instead of stories of supernatural adventures where women curse and prejudice is evil. I don’t know if she ever read any of my Tufa novels before she died; if she did, she never said anything good or bad about them to me, and once I moved out of the South, we lost touch. But I can’t imagine she approved of them.

And running across this dog-eared copy of Raney brought it all back. Since shame is the great Southern motivator, I’m certain this was her—genteel, of course, and with only my own best interests at heart—attempt to shame me into writing something that didn’t embarrass her and the family. Luckily, by that point I was secure enough in my own authorial voice that there was no way I’d ever try to write like this. Raney is a racist apologia disguised as harmless gentle humor, and whatever else you can say about my novels, they don’t apologize for racism.

And, lest you wonder, Raney has never gone out of print. Because the white “southern lit” crowd eats this stuff with a spoon.

So, sorry, Aunt A. Oh, and cool women do cuss.

#####

Addendum: There was a movie version of Raney made in 1997, but it’s impossible to find even a review of it, let alone a DVD or streaming copy. Only the IMDB page, and my own dim memory of an article in the Nashville Scene about its production, prove its existence. The lead actress apparently never made another film, and the director vanished as well. But it did have James Best in it.

[image error]June 30, 2021

“A Slight Hint of Lackadaisical Summer Torpor”: John Hartness on Writing and Publishing Southern Horror

Everyone knows the giants of southern literature, because they’re also giants of literature, full stop. William Faulkner, Walker Percy, Harper Lee, Robert Penn Warren, and so forth are perennials in lit courses and high school English classes. When it comes to horror, though, there isn’t the same respect. New England gets Stephen King and H.P. Lovecraft, but names like Manly Wade Wellman and Cherie Priest aren’t nearly as widely known.

North Carolina’s John G. Hartness has set out to change that. An award-winning author himself, he also runs Falstaff Books, an independent publisher tasked with bringing southern fantasy and horror to a wider audience. He was kind enough to answer a few questions about his endeavor and the philosophy behind it.

Alex Bledsoe: Why do you think Southern horror and fantasy isn’t as well known and celebrated as Southern literature in general?

John Hartness: I think horror in particular, and genre fiction as a whole, is kinda locked in a closet and fed through a slot in the door as a general rule, because there’s a segment of the book buying (and selling, and publishing, and writing) community that thinks that it’s “lesser” somehow, because it’s written with commercial intent. It goes to this bizarre concept we have of “doing it for the art,” as though artists don’t also have to pay a mortgage or, you know, buy food. The idea that commercial fiction is of lesser quality than “literary” fiction is abject horseshit. Shakespeare was a hack writing for his patron. Dickens was getting paid by the word to write serialized commercial fiction. The idea that a writer, or a work, cannot be both commercial and good at the same time, is some kind of weird BS that I can’t dive into without getting all historically sociopolitical on you. So basically Southern genre fiction doesn’t have the same high-tone cachet as “literary” fiction because some folx don’t think writers should make a living in their pajamas, just because they have to go into an office to do their job, and I go downstairs.

AB: Other than setting, what do you consider the essentials for weird fiction to call itself “Southern?”

JH: Even in the more pulp-styled Southern stuff that I write, there’s a pacing that is uniquely ours. It boils down to the way we meet and interact with people in the South, which is fifteen minutes of “how’s your mama?” and “now, where are your people from?” before we’ll tell the kid at the grocery store if we want paper or plastic. I exaggerate, but only slightly. I feel like Act 1 in a Southern novel tends to be a little longer, and the plot overall a little more circuitous, than in books set in other places. But where Southern fiction really sings is in the dialogue. There’s a music to the South that comes out when we speak, from the lilting, dancing minuets of South of Broad Charleston dialect, to the twangy, half-tuned banjo picking of West Virginia coal miners. The “Southern” accent is so broad, and so varied, that it’s almost like a New York accent. A person from Astoria sounds about as much like a person from the Upper East Side as someone from Savannah sounds like someone from LA (Lower Alabama ). There are more than half a dozen accents just in the Carolinas (and yes, I can adopt about five of them, depending on where I am and who I’m talking to – a theatre degree has its uses). So there needs to be that slight hint of lackadaisical summer torpor in the plotting, and there has to be music in the speech. It might not be pleasant music, but it’s music nonetheless.

AB: What inspired you to start your own publishing house? Why the name Falstaff?

JH: A couple of friends of mine asked me to beta read a book they were shopping, and give them feedback. I loved the book and told them if they didn’t sell it, I’d publish them. Six months later, I got the “were you serious?” email, and decided that since I was serious, I’d better figure out how to transition from self-publishing to publishing other people’s work. Five years and almost 250 titles later, I’m about to figure it out, I think. Another couple hundred books and I’ll know most of what I’m doing.

The Falstaff name came from my “career” as a poker blogger and journalist. I was playing poker with a friend at his house, and it was part of a gathering of poker bloggers, and we were (are) both named John. It gets confusing having someone always yelling your name and it not being you, especially if you’re a Leo (and therefore a narcissist) like me. So I asked for suggestions for a nickname, because I’ve never really had one that wasn’t egregiously insulting. Since I’m fat, my first name is John, and I have a theatre background, an overeducated friend of mine suggested Falstaff, after the character in Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry 4 & 5. My love for beer and the brewery of the same name didn’t figure into the suggestion at all, I’m sure. So I spent five years writing as Falstaff, and as John “Falstaff” Hartness, so when I transitioned from poker journalism to fiction (aka I got fired), I self-published under “Falstaff Books” to try and tie the branding all together.

AB: As a former winner of the Manly Wade Wellman prize, who else would you recommend to someone looking to see what’s out there in Southern weird fiction?

JH: Southern fiction is such a hugely diverse field that it’s really hard to narrow down. Michael G. Williams’ A Fall in Autumn, another Manly Wade Wellman Award winner, is a beautiful far-future LGBTQ+ noir detective novel. Jeff Strand is one of my favorite horror writers working today, and his stuff ranges from the hilarious to the horrific. We have a Falstaff title coming out late this year called The Devil Makes Three by Lucy Blue that I think is a truly astounding Southern Gothic horror novel dealing with racism and small town secrets that won’t stay buried, no matter how many bodies you pile on top of them. Cherie Priest has some fantastic stuff as well, from her Maplecroft novels (Lizzie Borden v. Cthulu) to Family Plot, where you can almost smell the Spanish moss. Stuart Jaffe’s Max Porter series of ghost detective stories have an awesome Southern setting and a great noir feel to them. And the Touch trilogy of novellas from A.G. Carpenter are spectacularly Southern and creepy.

Big thanks to John Hartness for taking the time to chat. Be sure and check out Falstaff Books for his latest, including this one, because, as the man himself says, “It’s a cat in a spacesuit. Why wouldn’t I promote that?”

[image error]February 20, 2020

Giants of West Tennessee: Jack Boone

NOTE: This is the latest in an occasional series about notable figures from my home region. These are, for the most part, personal reminiscences and opinions; where available, I’ll include links so interested readers can find out more.

While Memphis has its own vibrant literary history, rural west Tennessee suffers from a dearth of serious writers. The swamps, fields and people of Jackson, Bolivar, Adamsville, and so forth are definitely under-represented in literature.

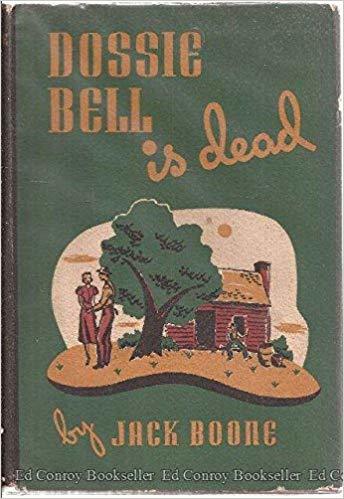

The original cover of Dossie Bell is Dead from 1939.

The original cover of Dossie Bell is Dead from 1939.John Talbott is trying to change that by recovering and re-publishing the work of a forgotten author. Jack Happel Boone (1903-1966) was born, and is buried, in my old stomping grounds of Gibson County, Tennessee. But he spent most of his life, and wrote about, Henderson and Chester County. His lone published novel, Dossie Bell is Dead, came out in 1939. But as his new bio page puts it, “An unruly lifestyle that served as his inspiration hindered what could have been a successful literary and academic career.”

Jack Happel Boone.

Jack Happel Boone.That might’ve been that, had it not been for John Talbott. His press, BrayBree, has reprinted Dossie Bell is Dead in new hardcover and paperback editions. More importantly, though, he’s been curating Boone’s unpublished work (including the sequel, Woods Girls) with plans to publish them as well. His goal: to bring Boone’s work to the audience that missed it the first time around.

Talbott himself gives a lot of the background on his efforts on this podcast, so rather than paraphrase it, I’ll let you listen. He was also kind enough to answer some of my additional questions about Boone’s work and its connection to its locale.

What are Jack Boone’s greatest strengths as a writer?

I think Boone’s greatest strengths as a writer lie in his ability as an observer of life around him at the time he was writing. The period in which he was writing was the late 1920’s through the late 1940’s primarily, and Boone was largely documenting a people in a remote area of West Tennessee known as The Hurst Nation, which he renamed, for literary purposes, The Tolby Nation. These were largely primitive people who were suspicious and retained many old Appalachian ways, old archaic ways, little known today. He was able to document many local and regional customs and habits, no longer seen or known, thus proving himself a historian and folklorist in many ways. To me, his ability to do document these people and to provide such a thorough picture that you can almost hear, see and sense them as you read is a testament to his ability as a writer.

What is it about Boone’s writing that speaks so strongly to you?

I would have to say that his understanding of his subjects is the attribute of his writing that truly reaches me. Boone spent significant time traveling around the Nation and other backwoods regions during the 1920’s and 1930’s and that time was very productive for him. He was able to gain an understanding of these people, their ways, their customs, their virtues, their vices and they limitations. His ability in turn to document all of this in literary form and report it to us in his writings is a feat. And it was almost lost. Yet even when saved, it was buried back and forgotten largely. Boone’s efforts and dedication in the face of contemporary frustration and rejection after the publication of Dossie Bell is Dead speaks to me. He never really gave up.

How does Dossie Bell is Dead compare to the unpublished material you’re working through?

Dossie Bell is Dead is, to me, a really good book. It documents vernacular and customs seldom heard or seen anymore, if at all. But it was just a good first effort and was well received, but he had better work still to come. Unfortunately, the times and circumstances prevented a further glimpse of his works. Now as I plow through thousands of pages of unpublished material including 5 novels and 40 or more short stories, I’m finding material that bests Dossie Bell. His works can be categorized in at least two headings: the serious, and the more sensational to be sold for quick money, i.e. pulp material. His serious works become more refined and better developed. I think the works after Dossie Bell are better works because we see his style developing and growing. His observations are more keen. His characters become more reflective and multi-dimensional as humans really are.

In the later works, mostly written from 1945 to 1954, Boone’s narrators, protagonists and primary characters do attain a depth such characters did not possess earlier in Boone’s career. For example, in Woods Girls, the sequel to Dossie Bell is Dead, Luster Holder is portrayed as a thinking, contemplative and savvy fellow, a far different portrayal than in Dossie Bell.

Inner struggles become more prevalent and more easily identifiable. The characters and the works themselves give us explicit examples of what now seem strange, quirky cultural phenomena and many of the short stories deal with a singular cultural event, as if Boone is reporting to us his findings….which in large measure is exactly what he is doing.

One thing that struck me about Dossie Bell is Dead is the complete absence of any civil authority. No one appeals to, or seems to expect any response from, law enforcement or local government. How accurate do you think that is, or did Boone exaggerate for effect, as Faulkner did with his Mississippian decadence?

During the time that Jack was writing, from the late 1920’s through the early 1950’s, there was even a lack of civil authority and law enforcement in and around Chester County, Tennessee and the Hurst Nation areas about which areas he was writing. What little law enforcement that existed was often absent from view due to corruption and bribery. Henderson, Chester County, the Hurst Nation area and McNairy County were all relatively “wide open.” Payoffs were prevalent and law enforcement had no desire to mix it up with the tougher elements of those who inhabited the backwoods areas of these counties. Therefore, Boone’s lack of depiction of the authorities is not surprising. In fact, in later stories and novels, Boone will actually depict law enforcement as corrupt good old boys components of machine politics, which it often was.

In my own writing, I’ve fully leaned in to the presence of music in the lives of my East Tennessee characters. In Dossie Bell, though, it’s virtually absent: no mention of musicians, or the radio, or church music (except for one description of Birdie looking for boys at a church event). Is that an accurate description of the times, or again, is it something Boone chooses for effect?

Interestingly, Boone seldom, if ever, depicted the musical element of local culture. In all of the thousands of pages of material I’ve sifted through to date, I’ve only encountered one peripheral reference to music in his works. That was in his unpublished novel, The Tumult and the Shouting. In that novel, his main character, David Forrest Brandon, finds himself on the outside fringes of a local Saturday night dance with an orchestra. His works are peculiar in their almost total lack of reference to music and this is peculiar because music in this region was integral to many families. I tend to think his failure to include musical references and situations was intentional.

So when can we expect more Boone releases?

I plan to have Woods Girls available by May or early June. I’m currently working on a collection of Neeley County stories and the publication date for that isn’t set. After that, there’ll still be a collection of pulp style stories and four more novels.

The pulp paperback retitled reprint.

The pulp paperback retitled reprint.Thanks to John Talbott for taking the time to talk to me. You can visit Jack Boone’s Facebook page here, and his BrayBree Press page here.