Amy Licence's Blog

April 17, 2019

Jeanne d'Albret: Heather Darsie's Anna of Cleves blog tour.

Today, I'm delighted to welcome Heather Darsie to my blog, the author of a new biography of Annea of Cleves, recently published by Amberley. Heather has written a piece on Jeanne d'Albret, a woman close to my own heart, which I know you'll enjoy reading.

Anna of Cleves’ Navarrese Sister-in-Law

By Heather R. Darsie

Jeanne d’Albret was born on 16 November 1528 to Marguerite d’Angoulême and Henri II of Navarre at the Parisian Saint Germain-en-Laye palace. Henri was Marguerite’s second husband. Marguerite had two children with Henri, but only Jeanne survived. Jeanne was the niece of the French king, Francois I, who dearly loved his elder sister Marguerite. Early on in her life, Jeanne became a pawn in the marriage market.

Jeanne was first betrothed to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s son, the future Philip II of Spain. Navarre was on the Spanish border, and wedding Jeanne to Philip would guarantee the consolidation of Navarre into Spain. Despite negotiations and bruits of a match between Jeanne and Philip during the earliest years of her life, this idea came to naught. Marguerite was vehemently against wedding Jeanne to Philip and must have felt some relief when the idea became moot.

By the late 1530s, Anna of Cleves’ younger brother Wilhelm became the Duke of Guelders and the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. He desperately wished to extend his power and so looked for a French or an Imperial bride. His attentions were on Christina of Denmark throughout 1538 to around 1540 before turning to a bride aligned with the French royal family. After striking up a friendly diplomatic relationship with Francis I, marriage negotiations began. After Francis determined against wedding any of his daughters to Wilhelm, his niece Jeanne d’Albret was settled upon.

Wilhelm was eleven years older than Jeanne. Their wedding took place in June 1541, when Wilhelm was twenty-four and Jeanne just shy of thirteen. The wedding itself was a gorgeous affair. After symbolically consummating the marriage with the very young Jeanne, Wilhelm left for his home in Jülich-Cleves-Berg. Jeanne remained in the care of her mother Marguerite. Jeanne was very much against her marriage to Wilhelm, to the point where she created two documents protesting the match which she had witnessed and notarized before the wedding. This, from a girl of twelve. Her willfulness and boldness would become her greatest assets later on in life.

Jeanne would never live in Jülich-Cleves-Berg, much to her relief. Jeanne loathed the idea of being reduced to a petty German princess. Jeanne’s marriage to Wilhelm was annulled in 1545 on the grounds of non-consummation and because of the official protests she crafted just before the wedding. Jeanne did not marry again until after the death of her uncle Francis I in March 1547. Henri II became King of France and married off his cousin Jeanne fairly quickly. On 20 October 1548, Jeanne married Antoine de Bourbon. The couple had five children, with only two surviving to adulthood.

By marrying Antoine de Bourbon, Henri had stronger control over the southern regions of France and the Kingdom of Navarre. Jeanne and Antoine’s marriage started off as a love match, but cooled within a few years due to Antoine’s philandering. On top of that, Jeanne and Antoine were growing to have very different opinions when it came to religion. Although Jeanne was raised from the age of two years at her uncle Francois I’s Roman-Catholic court, she was still the daughter of Marguerite d’Angoulême.

Marguerite’s interest in the Reformation increased over her lifetime. Marguerite was well-educated and she made a habit of attracting great minds to her court. Marguerite herself was a poetess and author. She was known to exchange correspondence with Calvinists and Reformists, and did her best to protect them. Marguerite died in 1549.

Jeanne and her husband Antoine ruled the Kingdom of Navarre after the death of Jeanne’s father on 25 May 1555. She was crowned in Pau on 18 August 1555 in a Roman Catholic ceremony, along with her husband. Jeanne declared herself a Calvinist on Christmas Day 1560, to the dismay of her husband.

As co-monarch then monarch of Navarre, Jeanne was able to declare Calvinism as the recognized religion of Navarre. After instituting Calvinism, monks and nuns were banned, and Catholic churches shut down. Jeanne was a very powerful Protestant monarch and a threat to her cousins, the kings of France.

The French Wars of Religion broke out in 1562. Antoine chose to support the Catholic faction. Jeanne remained a Calvinist and Antoine threatened to disavow their marriage. The dispute between husband and wife was resolved when Antoine died in November 1562 at the Siege of Rouen. Jeanne tried to be at her husband’s bedside while he was dying, but could not receive the proper safe conduct in time.

Jeanne remained mostly neutral during the first two wars because she had to protect her country from both Spain and France. By the time the Third War of French Religion started in 1568, Jeanne decided to support the Huguenots. Jeanne fled to La Rochelle with her son Henri and daughter Catherine. Jeanne made ample use of her knack for military strategy by guiding the Protestant forces from La Rochelle. In 1569, she wrote her memoir, Ample Declaration. Jeanne was instrumental in negotiating the Peace of Saint Germain-en-Laye in 1570, which ended the Third War of Religion.

The Peace of Saint Germain-en-Laye included the provision that Jeanne’s son marry Catherine de’ Medici’s daughter, a Roman Catholic French princess. The marriage negotiations were finalized in Spring 1571, and Henri of Navarre signed a marriage contract with Marguerite de Valois. Jeanne stayed in Paris over the rest of the spring and into early summer, indulging in shopping and preparing for her son’s wedding.

Jeanne died on 9 June 1572, after taking to her bed five days earlier. Her cause of death is unknown, though there is speculation that she succumbed to tuberculosis. She was buried beside her second husband, Antoine de Bourbon. He son Henri became the first Bourbon king when he ascended the Throne of France in 1589.

Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’ by Heather R. Darsie is released 15 April in the UK and 1 July in the US. If you live in the US and cannot wait until July, you can order a hardcover from the UK Amazon. The book can be purchased here:

UK Hardcover: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister/dp/1445677105/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=darsie&qid=1553980680&s=gateway&sr=8-1

UK Kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister-ebook/dp/B07PNQKR77/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1553980680&sr=8-1

US Hardcover: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1445677105?pf_rd_p=1cac67ce-697a-47be-b2f5-9ae91aab54f2&pf_rd_r=3N5CGT7W6TPG1X0AF7PZ

US Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister-ebook/dp/B07PNQKR77/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Sources & Suggested Reading

1. Darsie, Heather R. Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’. Stroud: Amberley Publishing (2019).

2. Roelker, Nancy Lyman. Queen of Navarre, Jeanne DAlbret: 1528–1572. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (1968).

3. Holt, Mack, ed. Renaissance and Reformation France 1500–1648. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

4. Mentzer, Raymond A., and Bertrand van Ruymbeke. A Companion to the Huguenots. Boston and Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2016.

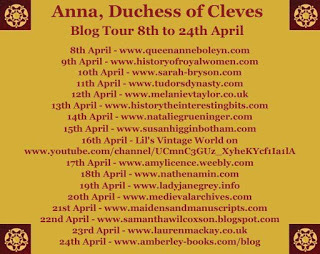

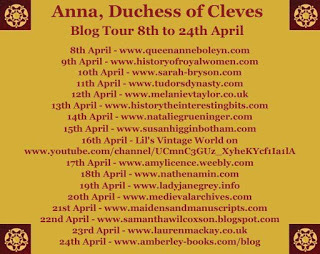

Look out for the rest of Heather's blog tour, which runs until 24 April:

Anna of Cleves’ Navarrese Sister-in-Law

By Heather R. Darsie

Jeanne d’Albret was born on 16 November 1528 to Marguerite d’Angoulême and Henri II of Navarre at the Parisian Saint Germain-en-Laye palace. Henri was Marguerite’s second husband. Marguerite had two children with Henri, but only Jeanne survived. Jeanne was the niece of the French king, Francois I, who dearly loved his elder sister Marguerite. Early on in her life, Jeanne became a pawn in the marriage market.

Jeanne was first betrothed to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s son, the future Philip II of Spain. Navarre was on the Spanish border, and wedding Jeanne to Philip would guarantee the consolidation of Navarre into Spain. Despite negotiations and bruits of a match between Jeanne and Philip during the earliest years of her life, this idea came to naught. Marguerite was vehemently against wedding Jeanne to Philip and must have felt some relief when the idea became moot.

By the late 1530s, Anna of Cleves’ younger brother Wilhelm became the Duke of Guelders and the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg. He desperately wished to extend his power and so looked for a French or an Imperial bride. His attentions were on Christina of Denmark throughout 1538 to around 1540 before turning to a bride aligned with the French royal family. After striking up a friendly diplomatic relationship with Francis I, marriage negotiations began. After Francis determined against wedding any of his daughters to Wilhelm, his niece Jeanne d’Albret was settled upon.

Wilhelm was eleven years older than Jeanne. Their wedding took place in June 1541, when Wilhelm was twenty-four and Jeanne just shy of thirteen. The wedding itself was a gorgeous affair. After symbolically consummating the marriage with the very young Jeanne, Wilhelm left for his home in Jülich-Cleves-Berg. Jeanne remained in the care of her mother Marguerite. Jeanne was very much against her marriage to Wilhelm, to the point where she created two documents protesting the match which she had witnessed and notarized before the wedding. This, from a girl of twelve. Her willfulness and boldness would become her greatest assets later on in life.

Jeanne would never live in Jülich-Cleves-Berg, much to her relief. Jeanne loathed the idea of being reduced to a petty German princess. Jeanne’s marriage to Wilhelm was annulled in 1545 on the grounds of non-consummation and because of the official protests she crafted just before the wedding. Jeanne did not marry again until after the death of her uncle Francis I in March 1547. Henri II became King of France and married off his cousin Jeanne fairly quickly. On 20 October 1548, Jeanne married Antoine de Bourbon. The couple had five children, with only two surviving to adulthood.

By marrying Antoine de Bourbon, Henri had stronger control over the southern regions of France and the Kingdom of Navarre. Jeanne and Antoine’s marriage started off as a love match, but cooled within a few years due to Antoine’s philandering. On top of that, Jeanne and Antoine were growing to have very different opinions when it came to religion. Although Jeanne was raised from the age of two years at her uncle Francois I’s Roman-Catholic court, she was still the daughter of Marguerite d’Angoulême.

Marguerite’s interest in the Reformation increased over her lifetime. Marguerite was well-educated and she made a habit of attracting great minds to her court. Marguerite herself was a poetess and author. She was known to exchange correspondence with Calvinists and Reformists, and did her best to protect them. Marguerite died in 1549.

Jeanne and her husband Antoine ruled the Kingdom of Navarre after the death of Jeanne’s father on 25 May 1555. She was crowned in Pau on 18 August 1555 in a Roman Catholic ceremony, along with her husband. Jeanne declared herself a Calvinist on Christmas Day 1560, to the dismay of her husband.

As co-monarch then monarch of Navarre, Jeanne was able to declare Calvinism as the recognized religion of Navarre. After instituting Calvinism, monks and nuns were banned, and Catholic churches shut down. Jeanne was a very powerful Protestant monarch and a threat to her cousins, the kings of France.

The French Wars of Religion broke out in 1562. Antoine chose to support the Catholic faction. Jeanne remained a Calvinist and Antoine threatened to disavow their marriage. The dispute between husband and wife was resolved when Antoine died in November 1562 at the Siege of Rouen. Jeanne tried to be at her husband’s bedside while he was dying, but could not receive the proper safe conduct in time.

Jeanne remained mostly neutral during the first two wars because she had to protect her country from both Spain and France. By the time the Third War of French Religion started in 1568, Jeanne decided to support the Huguenots. Jeanne fled to La Rochelle with her son Henri and daughter Catherine. Jeanne made ample use of her knack for military strategy by guiding the Protestant forces from La Rochelle. In 1569, she wrote her memoir, Ample Declaration. Jeanne was instrumental in negotiating the Peace of Saint Germain-en-Laye in 1570, which ended the Third War of Religion.

The Peace of Saint Germain-en-Laye included the provision that Jeanne’s son marry Catherine de’ Medici’s daughter, a Roman Catholic French princess. The marriage negotiations were finalized in Spring 1571, and Henri of Navarre signed a marriage contract with Marguerite de Valois. Jeanne stayed in Paris over the rest of the spring and into early summer, indulging in shopping and preparing for her son’s wedding.

Jeanne died on 9 June 1572, after taking to her bed five days earlier. Her cause of death is unknown, though there is speculation that she succumbed to tuberculosis. She was buried beside her second husband, Antoine de Bourbon. He son Henri became the first Bourbon king when he ascended the Throne of France in 1589.

Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’ by Heather R. Darsie is released 15 April in the UK and 1 July in the US. If you live in the US and cannot wait until July, you can order a hardcover from the UK Amazon. The book can be purchased here:

UK Hardcover: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister/dp/1445677105/ref=sr_1_1?keywords=darsie&qid=1553980680&s=gateway&sr=8-1

UK Kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister-ebook/dp/B07PNQKR77/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1553980680&sr=8-1

US Hardcover: https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1445677105?pf_rd_p=1cac67ce-697a-47be-b2f5-9ae91aab54f2&pf_rd_r=3N5CGT7W6TPG1X0AF7PZ

US Kindle: https://www.amazon.com/Anna-Duchess-Cleves-Beloved-Sister-ebook/dp/B07PNQKR77/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Sources & Suggested Reading

1. Darsie, Heather R. Anna, Duchess of Cleves: The King’s ‘Beloved Sister’. Stroud: Amberley Publishing (2019).

2. Roelker, Nancy Lyman. Queen of Navarre, Jeanne DAlbret: 1528–1572. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press (1968).

3. Holt, Mack, ed. Renaissance and Reformation France 1500–1648. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

4. Mentzer, Raymond A., and Bertrand van Ruymbeke. A Companion to the Huguenots. Boston and Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2016.

Look out for the rest of Heather's blog tour, which runs until 24 April:

Published on April 17, 2019 07:29

November 10, 2017

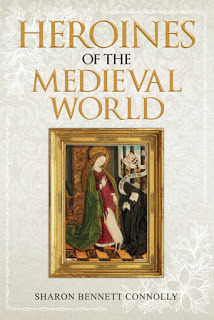

"Heroines of the Medieval World" Book Extract: Joan of Kent.

Today, I'm delighted to be part of a blog tour for an exciting new book, Heroines of the Medieval World, by Sharon Bennett Connolly. After making her blog, "History, The Interesting Bits", a resounding success, Sharon has used her first book to explore the lives of many long-overlooked women who lived remarkable lives. Today's extract is about Joan of Kent, wife of Edward, the Black Prince:

The leading beauty of her day, Joan had little to offer a potential suitor beyond her looks and keen intelligence; Froissart called her ‘the most beautiful woman in all the realm of England and the most loving’. She had grown up in the same household as Edward III’s eldest children – his son and heir Edward and his daughters Isabella and Joan. Around the age of eleven or twelve, it seems Joan of Kent secretly married, or promised to marry, Thomas Holland. Holland was a knight of the royal household, a soldier of some renown and, at twenty-four, twice Joan’s age. Modern sensibilities make us cringe at Joan’s tender age but, although it was young even for the period, an eleven-year-old bride was not unheard of. Their relationship remained a secret, however, and the couple had never obtained the king’s consent.

Just a few short months later, Holland left to go on Crusade. In 1341, while Holland was away crusading in Prussia, Joan’s mother, Margaret Wake, arranged an advantageous marriage for her daughter to William Montagu, 2nd Earl of Salisbury. Whether Margaret knew about the extent of Joan’s relationship with Holland is uncertain – it may be that she believed Joan was infatuated with the landless knight and hoped that marrying her to Montagu would cure the pre-teen of puppy love.

By 1341 Joan and Montagu were married. Thomas Holland, however, didn’t appear to be in a rush to return to claim his wife; once his crusading duties were done, he spent the next few years campaigning in Europe. In 1342–3 he fought in Brittany with the king, and was probably in Granada with the Earl of Derby by 1343. In 1345 he was back in Brittany, and was at the Siege of Caen in 1346; a battle in which Joan’s other ‘husband’, Montagu, may also have taken part. Holland not only gained a reputation as a soldier but also made his fortune when he sold his prisoner, the Count of Eu, Constable of France, to Edward III for 80,000 florins.

When he returned to England, Thomas Holland joined the Earl of Salisbury’s household as his steward, and found himself in the strange position of working for the man who was married to his wife. In May 1348, Holland petitioned the pope, stating that Joan had been forced into her marriage with Salisbury. He went on to say that Joan had previously agreed to marry him and their relationship had been consummated. William contested the annulment; however, when it came time for Joan to testify, she supported Holland’s claims.

It took eighteen months for Joan’s marital status to be resolved. In the meantime, England was in the grip of the Black Death, the bubonic plague. To lift the country’s spirits, Edward III arranged a grand tournament to be held at Windsor, on St George’s Day, 23 April 1349. The knights in contention were the founder members of the Order of the Garter; England’s greatest chivalric order, consisting of the king and twenty-five founder knights. The order was probably founded in 1348, though the date is uncertain. This tournament included William Montagu and Thomas Holland, both Joan’s husbands. Joan herself is a part of the legend of the foundation of the Order of the Garter. She is said to be the lady who lost her garter during a ball celebrating the fall of Calais. Edward III is said to have returned the item to the twenty-year-old damsel with the words ‘honi soit qui mal y pense’ (‘evil to him who evil thinks’). Although the story is probably apocryphal, Joan’s connection with the inaugural tournament is all too true; she brought an added spice to the St George’s Day tournament of 1349. Her current husband, the Earl of Salisbury, fought on the king’s team, while Sir Thomas Holland was on the side of Prince Edward. Joan’s two husbands faced each other across the tournament field, with the object of their affection watching from the stands. Although the results of the tournament are obscure, Joan’s marital status was decided by Papal Bull, on 13 November 1349, when the pope ordered her to divorce Salisbury and return to Holland, a ruling she seems to have been happy to comply with.

Montagu wasted little time in finding himself another wife and married Elizabeth de Mohun shortly after the annulment had been granted. Elizabeth was the daughter of John, Lord Mohun of Dunster, and, given that she was born around 1343, was only six or seven at the time of the marriage. Several years later, they would have one child, a son, William, born in 1361. William was married in 1378, to Elizabeth FitzAlan, daughter of his father’s companionin-arms Richard, Earl of Arundel. Their happiness was short-lived, however, when William died after only four years of marriage, in a tragedy that must have rocked Montagu to the core – on 6 August 1382, young William was killed by his own father, the earl, in a tilting match at Windsor.

Sharon Bennett Connolly, has been fascinated by history for over 30 years now and even worked as a tour guide at historical sites, including Conisbrough Castle. Born in Yorkshire, she studied at University in Northampton before working in Customer Service roles at Disneyland in Paris and Eurostar in London.

She is now having great fun, passing on her love of the past to her son, hunting dragons through Medieval castles or exploring the hidden alcoves of Tudor Manor Houses.

Having received a blog as a gift, History…the Interesting Bits, Sharon started researching and writing about the lesser-known stories and people from European history, the stories that have always fascinated. Quite by accident, she started focusing on medieval women. And in 2016 she was given the opportunity to write her first non-fiction book, Heroines of the Medieval World, which was published by Amberley in September 2017. She is currently working on her second non-fiction book, Silk and the Sword: The Women of the Norman Conquest, which will be published by Amberley in late 2018.

Links: Blog; https://historytheinterestingbits.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Thehistorybits/

Twitter: @Thehistorybits

Book: Amazon UK https://www.amazon.co.uk/Heroines-Medieval-Sharon-Bennett-Connolly/dp/1445662647/

Amberley https://www.amberley-books.com/heroin...

Amazon US https://www.amazon.com/dp/1445662647/

You can find the other blogs that have taken part in the tour so far, with their extracts, here:

· Day 1: http://anniewhitehead2.blogspot.co.uk/2017/10/heroines-of-medieval-age-review.html/ · Day 2: https://sarah-bryson.com/2017/10/31/sharon-bennett-connolly-book-tour-day-2/ · Day 3: http://www.susanhigginbotham.com/blog/posts/guest-post-by-sharon-bennett-connolly-joan-lady-of-wales/ · Day 4: https://henrytudorsociety.com/2017/11/02/all-for-love-katherine-swnyford-and-joan-beaufort/· Day 5: https://tonyriches.blogspot.co.uk/2017/11/book-launch-blog-tour-heroines-of.html · Day 6: http://www.medievalarchives.com/MedievalHeroines · Day 7: http://kristiedean.com/book-review-heroines-of-the-medieval-world/ · Day 8: http://wp.me/p7hrUg-b6 (Stephanie Churchill)· Day 9: http://bit.ly/2mqBQC7 (Lil’s Vintage World)· Day 10: http://thereview2014.blogspot.co.uk/2017/11/heroines-of-medieval-world-blog-tour.html· Day 1: https://www.facebook.com/TheGorgeousHistoryGeeks/ · Extra link a book review posted before the blog tour by Tonyhttp://tonyriches.blogspot.co.uk/2017/10/book-review-heroines-of-medieval-world.html

Published on November 10, 2017 01:34

October 13, 2017

Book Tour, "The King's Pearl: Henry VIII and his Daughter Mary" by Melita Thomas.

Today, I'm delighted to be hosting Melita Thomas, director of Tudor Times Ltd, to promote the publication of her book "The King's Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary." (Amberley, Sept 2017)

Melita has kindly shared with us an interesting extract about Mary's relationship with her uncle, Emperor Charles V:

‘My well-beloved future Empress: Mary and the Emperor Charles V

One of the most important influences in Mary’s life was her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, a man who ruled over more territory in Europe than any man since Charlemagne. Born in 1500, to Mary’s aunt Juana and Duke Philip of Burgundy, Charles became Duke of Burgundy in 1506, and King of Spain a month before Mary’s birth. Before Mary was four, he was also Emperor.

England and Burgundy had been allies for many years, and Spain and England since the treaty of Medina del Campo of 1489, which had agreed the marriage of Mary’s mother, Katharine of Aragon, to Arthur, Prince of Wales. When Henry VIII came to the throne and married his late brother’s widow, the alliance with Charles was renewed.

Henry’s life-long ambition was to reconquer France, and similarly, Charles, although he had no designs on French territory, was eager to defeat François of France in the disputed Italian peninsula, and prevent French expansion. Much of the diplomacy of Henry and Charles throughout Henry’s reign, was thus dedicated to their combined assaults on François I, although both, at times, were also allied to France.

In 1521, the Treaty of London, which Henry and François had signed in 1518, and which was to be cemented by the marriage of Mary and François’ young son, was under strain, at the same time as Charles and François were at daggers drawn. Using the cover story of attempting mediation between the warring parties, Cardinal Wolsey, Henry’s chief minister, travelled to Charles in his Burgundian capital of Bruges and negotiated a secret agreement, under which Mary would marry the Emperor. At that time, she was five, and Charles was twenty-one. It was agreed that the following year, he would visit England and sign the treaty in person.

Accordingly, in June 1522, Charles arrived in England, where he was wined, dined and entertained for a month. He met the six-year-old Mary, who seems to have formed as much attachment to him as a little girl can to a kind, older male relative. The court was first at Greenwich, and later, Mary joined them at Windsor Castle, where a treaty was formally agreed, according to which Charles, would marry Mary, when she reached the minimum marriageable age of twelve. There was a caveat, that the Pope had to grant a dispensation for the match, because of the close blood relationship of the two. He could not be asked immediately, because neither party wished the French to be alerted to the treaty – Charles was already bound to marry one of François’ daughters and Mary was still betrothed to the French Dauphin.

All seemed set fair for Mary to have a glorious future as Holy Roman Empress. Mary wore a brooch with the words ‘the Emperor’ enamelled on it, and Charles would ask after his ‘beloved future Empress’. The only fly in the ointment, so far as Henry was concerned, was that he had been obliged to agree that, if Mary had no brothers, she would inherit the throne of England. But Henry continued to hope that Katharine would bear a son, and it was not until 1524, that he seems to have accepted that that had become impossible.

In 1525, Charles won a stunning victory over the French at the battle of Pavia. King François was captured, and it seemed to Henry that, with his ally’s support, he could now sweep into France, to be crowned king, just as Henry VI of England had been, a hundred years before. But Charles hesitated. He had run out of money, and now that he had secured Italy, he was disinclined to interfere in France. He refused to give Henry more than moral support, and permission to raise troops in Charles’ territories, at Henry’s own expense. In the meantime, he was so short of cash himself that he needed Mary to be sent to him immediately, along with her dowry.

Henry was appalled – Charles’ demands were contrary to the treaty, and he could not let Mary, his only legitimate child, leave the country so young. She could not be married for another three years – and even that would be too soon, in Henry’s reckoning. Aware of the dangers of early childbirth, as suffered by his grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry was adamant that Mary could not consummate any marriage until she was sufficiently physically mature. But he could not let Mary go to Spain without an immediate wedding, lest Charles hold her hostage.

But Charles would not wait – desperate for cash, he married Isabella of Portugal, whose brother was offering a dowry of 1m ducats, more than twice what Henry was offering with Mary, although, as the English pointed out, she had the chance of bringing the crown of England with her.

Henry was mortified, and his anger against Charles was another nail in the coffin of his relationship with his wife. Katharine could bear no more children, and, whilst in earlier years, Henry had been deeply attached to his wife, they had grown apart, and he was enamoured of a young woman of the court, Anne Boleyn.

There is no record of Mary’s reaction to being jilted by Charles – it does not seem to have affected her view of him, and Katharine, although it made her life more difficult, perhaps accepted it as a mere matter of policy.

It was certainly to Charles that Katharine turned in 1527 when she heard rumours that Henry intended to request the Pope for an annulment of their marriage. She sent a secret messenger to her nephew, and he reacted as she hoped. He wrote to Henry, begging him to desist from taking such a scandalous step, and put pressure on the pope to reject Henry’s request. Not long after, Charles dominated the situation, when his troops sacked Rome, and effectively delivered the pope, Clement VII, into Imperial control.

But, although for the next nine years, until Katharine’s death in 1536, Charles exhorted Henry, nagged the pope, and send endless messages of support to his aunt and cousin, at no time did he think of involving himself more directly. He was attached to both Katharine and Mary, but not to the extent of doing more than writing letters, and offering consolation. He had neither the inclination nor the resources to take any military action, nor would he damage his own native Burgundy’s economy by banning trade with England.

Far more enthusiastically engaged with Mary and Katharine was Charles’ ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. Chapuys constantly urged Charles to do more, and gave Mary as much moral support as he could – he also gave her the impression that Charles was more emotionally invested in her situation than was probably the case.

It crossed Charles’ mind that it would be useful to have Mary in his own hands, and he gave some encouragement to the idea that she should try to escape – at one time, there was even a ship in the Thames that had orders to take her to safety in The Netherlands, but he was never strongly in favour of an escape – to give succour to the King of England’s daughter would be an open act of aggression, that would be of no benefit of Charles - nothing would be more likely than that it would drive Henry would form an alliance with France to Charles’ detriment in Italy.

As time passed, and it became apparent that Henry was not going to take Katharine back, Charles began to put his own needs for warmer relations between the countries above the welfare of his aunt and Mary. He made it clear via conversations between Chapuys and Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, towards the end of 1535, that he sought a rapprochement. When Katharine died in January 1536, Charles was even willing to go so far as to offer to mediate with the Pope to have Anne Boleyn recognised as Henry’s wife. As for Mary, although he did not want her to sign the oaths of Succession and Supremacy, which proclaimed Katharine’s marriage invalid, and Henry as Supreme Head of the Church in England, he advised her to sign, if her life were in danger.

Mary did sign, although not until after the execution of Anne Boleyn, and was restored to paternal favour. But she did not forget the support that Charles had given her – and perhaps valued it more than it was worth. Charles saw the opportunity to improve relations with England, and suggested a marriage between Mary and their mutual cousin, Dom Luis of Portugal. He promoted this idea for some years, but nothing came of it.

Later, after Charles was widowed, there was even talk of reviving the match between him and Mary, but although, according to Chapuys, the emperor’s ‘mouth was made to water’ at the thought of the now-mature Mary, there could be no possibility of the emperor marrying a woman considered illegitimate in her own country, and Henry could not be persuaded to change her status, especially as he now had a son, Edward, and did not want to risk Mary, with all of the resources that would be available to her as empress, trying to oust Edward from the succession.

Throughout Henry’s reign, Charles was rewarded for his support for Mary by her confidence, and her willingness to share information with his envoys about events in England. It is difficult to ascertain whether she was passing on more details of what was going on in England than Henry realised, or whether he was deliberately feeding her information he wanted Charles to hear, and Mary, either wittingly or not, was being used as a diplomatic pawn.

Charles’ concern for Mary became one of her psychological mainstays – and he was to reap the rewards of his efforts, however limited, during her own reign.

"The King's Pearl" is available now from Amberley Publishing.

Melita Thomas is the co-founder and editor of Tudor Times, a repository of information about Tudors and Stewarts in the period 1485-1625 www.tudortimes.co.uk

Melita has loved history since being mesmerised by the BBC productions of ‘The Six Wives of Henry VIII’ and ‘Elizabeth R’, when she was a little girl. After that, she read everything she could get her hands on about this most fascinating of dynasties. Captivated by the story of the Lady Mary galloping to Framingham to set up her standard and fight for her rights, Melita began her first book about the queen when she was 9. The manuscript is probably still in the attic.

Whilst still pursuing a career in business, Melita took a course on writing biography, which led her and her business partner to the idea for Tudor Times, and gave her the inspiration to begin writing about Mary again.

‘The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary’ is her first book. She has several ideas for a second project, and hopes to settle on one and begin writing by the end of the year.

In her spare time, Melita enjoys long distance walking. She is attempting to walk around the whole coast of Britain, and you can follow her progress here. https://mgctblog.com/

Melita has kindly shared with us an interesting extract about Mary's relationship with her uncle, Emperor Charles V:

‘My well-beloved future Empress: Mary and the Emperor Charles V

One of the most important influences in Mary’s life was her cousin, the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, a man who ruled over more territory in Europe than any man since Charlemagne. Born in 1500, to Mary’s aunt Juana and Duke Philip of Burgundy, Charles became Duke of Burgundy in 1506, and King of Spain a month before Mary’s birth. Before Mary was four, he was also Emperor.

England and Burgundy had been allies for many years, and Spain and England since the treaty of Medina del Campo of 1489, which had agreed the marriage of Mary’s mother, Katharine of Aragon, to Arthur, Prince of Wales. When Henry VIII came to the throne and married his late brother’s widow, the alliance with Charles was renewed.

Henry’s life-long ambition was to reconquer France, and similarly, Charles, although he had no designs on French territory, was eager to defeat François of France in the disputed Italian peninsula, and prevent French expansion. Much of the diplomacy of Henry and Charles throughout Henry’s reign, was thus dedicated to their combined assaults on François I, although both, at times, were also allied to France.

In 1521, the Treaty of London, which Henry and François had signed in 1518, and which was to be cemented by the marriage of Mary and François’ young son, was under strain, at the same time as Charles and François were at daggers drawn. Using the cover story of attempting mediation between the warring parties, Cardinal Wolsey, Henry’s chief minister, travelled to Charles in his Burgundian capital of Bruges and negotiated a secret agreement, under which Mary would marry the Emperor. At that time, she was five, and Charles was twenty-one. It was agreed that the following year, he would visit England and sign the treaty in person.

Accordingly, in June 1522, Charles arrived in England, where he was wined, dined and entertained for a month. He met the six-year-old Mary, who seems to have formed as much attachment to him as a little girl can to a kind, older male relative. The court was first at Greenwich, and later, Mary joined them at Windsor Castle, where a treaty was formally agreed, according to which Charles, would marry Mary, when she reached the minimum marriageable age of twelve. There was a caveat, that the Pope had to grant a dispensation for the match, because of the close blood relationship of the two. He could not be asked immediately, because neither party wished the French to be alerted to the treaty – Charles was already bound to marry one of François’ daughters and Mary was still betrothed to the French Dauphin.

All seemed set fair for Mary to have a glorious future as Holy Roman Empress. Mary wore a brooch with the words ‘the Emperor’ enamelled on it, and Charles would ask after his ‘beloved future Empress’. The only fly in the ointment, so far as Henry was concerned, was that he had been obliged to agree that, if Mary had no brothers, she would inherit the throne of England. But Henry continued to hope that Katharine would bear a son, and it was not until 1524, that he seems to have accepted that that had become impossible.

In 1525, Charles won a stunning victory over the French at the battle of Pavia. King François was captured, and it seemed to Henry that, with his ally’s support, he could now sweep into France, to be crowned king, just as Henry VI of England had been, a hundred years before. But Charles hesitated. He had run out of money, and now that he had secured Italy, he was disinclined to interfere in France. He refused to give Henry more than moral support, and permission to raise troops in Charles’ territories, at Henry’s own expense. In the meantime, he was so short of cash himself that he needed Mary to be sent to him immediately, along with her dowry.

Henry was appalled – Charles’ demands were contrary to the treaty, and he could not let Mary, his only legitimate child, leave the country so young. She could not be married for another three years – and even that would be too soon, in Henry’s reckoning. Aware of the dangers of early childbirth, as suffered by his grandmother, Lady Margaret Beaufort, Henry was adamant that Mary could not consummate any marriage until she was sufficiently physically mature. But he could not let Mary go to Spain without an immediate wedding, lest Charles hold her hostage.

But Charles would not wait – desperate for cash, he married Isabella of Portugal, whose brother was offering a dowry of 1m ducats, more than twice what Henry was offering with Mary, although, as the English pointed out, she had the chance of bringing the crown of England with her.

Henry was mortified, and his anger against Charles was another nail in the coffin of his relationship with his wife. Katharine could bear no more children, and, whilst in earlier years, Henry had been deeply attached to his wife, they had grown apart, and he was enamoured of a young woman of the court, Anne Boleyn.

There is no record of Mary’s reaction to being jilted by Charles – it does not seem to have affected her view of him, and Katharine, although it made her life more difficult, perhaps accepted it as a mere matter of policy.

It was certainly to Charles that Katharine turned in 1527 when she heard rumours that Henry intended to request the Pope for an annulment of their marriage. She sent a secret messenger to her nephew, and he reacted as she hoped. He wrote to Henry, begging him to desist from taking such a scandalous step, and put pressure on the pope to reject Henry’s request. Not long after, Charles dominated the situation, when his troops sacked Rome, and effectively delivered the pope, Clement VII, into Imperial control.

But, although for the next nine years, until Katharine’s death in 1536, Charles exhorted Henry, nagged the pope, and send endless messages of support to his aunt and cousin, at no time did he think of involving himself more directly. He was attached to both Katharine and Mary, but not to the extent of doing more than writing letters, and offering consolation. He had neither the inclination nor the resources to take any military action, nor would he damage his own native Burgundy’s economy by banning trade with England.

Far more enthusiastically engaged with Mary and Katharine was Charles’ ambassador, Eustace Chapuys. Chapuys constantly urged Charles to do more, and gave Mary as much moral support as he could – he also gave her the impression that Charles was more emotionally invested in her situation than was probably the case.

It crossed Charles’ mind that it would be useful to have Mary in his own hands, and he gave some encouragement to the idea that she should try to escape – at one time, there was even a ship in the Thames that had orders to take her to safety in The Netherlands, but he was never strongly in favour of an escape – to give succour to the King of England’s daughter would be an open act of aggression, that would be of no benefit of Charles - nothing would be more likely than that it would drive Henry would form an alliance with France to Charles’ detriment in Italy.

As time passed, and it became apparent that Henry was not going to take Katharine back, Charles began to put his own needs for warmer relations between the countries above the welfare of his aunt and Mary. He made it clear via conversations between Chapuys and Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, towards the end of 1535, that he sought a rapprochement. When Katharine died in January 1536, Charles was even willing to go so far as to offer to mediate with the Pope to have Anne Boleyn recognised as Henry’s wife. As for Mary, although he did not want her to sign the oaths of Succession and Supremacy, which proclaimed Katharine’s marriage invalid, and Henry as Supreme Head of the Church in England, he advised her to sign, if her life were in danger.

Mary did sign, although not until after the execution of Anne Boleyn, and was restored to paternal favour. But she did not forget the support that Charles had given her – and perhaps valued it more than it was worth. Charles saw the opportunity to improve relations with England, and suggested a marriage between Mary and their mutual cousin, Dom Luis of Portugal. He promoted this idea for some years, but nothing came of it.

Later, after Charles was widowed, there was even talk of reviving the match between him and Mary, but although, according to Chapuys, the emperor’s ‘mouth was made to water’ at the thought of the now-mature Mary, there could be no possibility of the emperor marrying a woman considered illegitimate in her own country, and Henry could not be persuaded to change her status, especially as he now had a son, Edward, and did not want to risk Mary, with all of the resources that would be available to her as empress, trying to oust Edward from the succession.

Throughout Henry’s reign, Charles was rewarded for his support for Mary by her confidence, and her willingness to share information with his envoys about events in England. It is difficult to ascertain whether she was passing on more details of what was going on in England than Henry realised, or whether he was deliberately feeding her information he wanted Charles to hear, and Mary, either wittingly or not, was being used as a diplomatic pawn.

Charles’ concern for Mary became one of her psychological mainstays – and he was to reap the rewards of his efforts, however limited, during her own reign.

"The King's Pearl" is available now from Amberley Publishing.

Melita Thomas is the co-founder and editor of Tudor Times, a repository of information about Tudors and Stewarts in the period 1485-1625 www.tudortimes.co.uk

Melita has loved history since being mesmerised by the BBC productions of ‘The Six Wives of Henry VIII’ and ‘Elizabeth R’, when she was a little girl. After that, she read everything she could get her hands on about this most fascinating of dynasties. Captivated by the story of the Lady Mary galloping to Framingham to set up her standard and fight for her rights, Melita began her first book about the queen when she was 9. The manuscript is probably still in the attic.

Whilst still pursuing a career in business, Melita took a course on writing biography, which led her and her business partner to the idea for Tudor Times, and gave her the inspiration to begin writing about Mary again.

‘The King’s Pearl: Henry VIII and his daughter Mary’ is her first book. She has several ideas for a second project, and hopes to settle on one and begin writing by the end of the year.

In her spare time, Melita enjoys long distance walking. She is attempting to walk around the whole coast of Britain, and you can follow her progress here. https://mgctblog.com/

Published on October 13, 2017 01:39

March 14, 2016

On the Trail of the Yorks: Kristie Dean's exciting new book.

I'm delighted to welcome the fabulous Kristie Dean, author of "The World of Richard III," whose new book "On the Trail of the Yorks" has just been released by Amberley Publishing. Kristie joins us to share an extract of her new work, focussing on the buildings which the York family owned and inhabited, with details gathered on her own extensive travels:

From "On the Trail of the Yorks:"

The gatehouse, Wigmore Castle.

Wigmore Castle came to Richard, Duke of York, as part of his Mortimer inheritance. The original castle is said to have been built by William Fitz Osbern. After his death, his son Roger de Breteuil inherited his lands in England. The lands were forfeited to the crown when Roger entered into rebellion against the king and was imprisoned.

The king granted Wigmore, along with other lands, to Ralph de Mortimer. Most of the construction of the castle was completed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Roger Mortimer renovated and rebuilt large sections of Wigmore. Since the family was powerful and wealthy, the castle probably reflected their status. In the early fourteenth century, Mortimer hosted a large tournament here, inviting the young King Edward III and his mother, Isabella. Certainly, the castle contained lavish accommodations in which to house the royal party.

Wigmore Castle was originally of motte-and-bailey construction. The later sandstone keep was built atop the motte, and a strong curtain wall with at least four sturdy towers surrounded the entire fortress. The fortification was necessary since the castle was besieged at least once in its early history.

According to The History of the King’s Works, there are no records of the architectural history of the castle between 1461 and 1485. The castle was in ruins by the sixteenth century, and was further dismantled during the Civil War.

Richard, Duke of York, and Wigmore

Soon after his loss of the Protectorate, York realised that he needed to leave court for a time. He first retreated to Sandal Castle, but soon decided he needed to move closer to Wales. H. T. Evans in his book Wales and the Wars of the Roses says Margaret of Anjou and Jasper Tudor had been busy consolidating a power base in Wales. Realising he needed to go where his support was greatest, York chose to remove himself to Wigmore sometime in October. Cecily had been at Caister Castle in Norfolk, so it is doubtful she joined him here.

Edward and Wigmore

As Wigmore was one of his father’s holdings, Edward would have spent time here while a child. Perched on a ridge west of Wigmore village, the castle had three baileys. Edward and his family would have entered the castle by crossing the drawbridge to the first gatehouse, and then over another drawbridge to the inner gatehouse where the portcullis would have been raised. The keep was high on the motte, allowing for a spectacular view. While here, Edward and Edmund would have hunted in the park near the castle.

After learning of his father’s death, Edward continued to raise troops among the Welsh Marches. Hearing that Jasper Tudor was heading to Hereford, Edward made his way to intercept him. Wigmore is not far from Hereford and was a logical choice to lodge Edward and his troops.

Passing by the parish church of St James, Edward and his men would have made their way up the hill to the castle where Edward lodged in the great chambers in the keep. His men would have stayed in either one of the lodging towers, in the timber-framed buildings along the curtain wall or in the Great Hall.

Knowing that his family’s future rested on his shoulders, Edward possibly passed a sleepless night within the palatial rooms of Wigmore, kept warm by one of the fireplaces within the keep. Before the first rays of light flooded through the intricately cut stonework of the chamber’s windows, he was organising his men to march over the frosted moors towards Tudor’s troops.

Richard III and Wigmore

After Richard became king, he granted the stewardship of Wigmore to William Herbert. Herbert had married Katherine Plantagenet, who was Richard’s illegitimate daughter. Wigmore was only one of the many grants that Richard gave to Herbert and to his daughter.

About the Author:

Kristie Dean is passionate about the medieval era. This passion ignited an interest in history that drove her to gain her master’s degree in history. Today, she enjoys instilling a love of history in her students. Her first book, On the Trail of Richard III (original title: The World of Richard III ), focused on the controversial king.

Many thanks to Kristie for sharing her work with us. Her new book, and her first one, are available from Amazon from tomorrow, 15 March.

Published on March 14, 2016 04:13

May 20, 2015

Call for Submissions: Envisioning the Tudor Woman: Historical and Modern Representations of Women 1485-1600

Submissions for Envisioning the Tudor Woman: Historical and Modern Representations of Women 1485-1600

We invite proposals for papers to be included in a multidisciplinary edited volume entitled Envisioning the Tudor Woman: Historical and Modern Representations of Women from the Tudor Era. Please submitting a proposal before July 1 2015; the final deadline for complete essays will be December 1, 2015. Papers must be between 4000 – 6,000 words in length and focus on the way women from 1485-1603 have been depicted in art and culture.

This edited volume aims to bring together scholars from a variety of fields to provide a variety of different perspectives to the way in which Tudor women – famous, infamous, or typical -- have been represented both in their own era and in other historical periods. Conceptualizations of how Tudor women looked, felt, and behaved have been used lavishly in literature and media, nearly saturating popular culture and historical fiction. What does history have to say about Tudor women and their role in their culture and society? In what ways were Tudor women portrayed by their contemporaries? How do the Tudor women of fiction align or diverge from historical facts? In what ways do constructions of Tudor women reflect the gender and sociocultural ideologies of those imagining them?

Topics might include, but are not limited to:Tudor femininity in literature and narrative fictionArtistic presentations of Tudor women past and presentGender ideologies and the conceptualization of Tudor womenTudor women from a feminist perspective The roles of Tudor women in their own cultureThe contemporary fan culture surrounding famous Tudor womenTudor women as a method to promote British tourismWomen depicted in Tudor poetry and dramaMedical explanations of femininity in Tudor cultureTudor women in twentieth century romance novels

Please contact Amy Licence (amy_licence@yahoo.co.uk) or Kyra Kramer (kyra.cornelius.kramer@gmail.com) or find us on facebook to submit or discuss proposals.

Published on May 20, 2015 02:00

March 16, 2015

Virginia Woolf’s "The Voyage Out" turns 100: The Difficult Birth of a Debut Novel.

The end of March 2015 marked the centenary of Virginia Woolf’s debut as a novelist. Although she had already published a number of reviews and filled notebooks and diaries with her spidery hand, the thirty-three-year-old had been working on her first full-length fiction for around eight years. It had indeed been a difficult birth, an agonising process of editing, criticism and revision which took her through at least five drafts. In fact, the novel had been scheduled for publication by Duckworth and Co. a whole two years earlier, in 1913, then delayed as Virginia’s mental health plunged her into a post-marital, post-completion depression and anxiety. Copies of The Voyage Out finally appeared on March 26, 1915.

As a debut novel, it is a mixed bag, as, to be fair, most debut novels are. Telling the story of the young Rachel Vinrace’s journey of discovery on board ship heading for South America, it combines the lucid and beautiful prose we expect from Woolf, with unevenly drawn characters and the heroine’s frustratingly premature death. While the passages describing Rachel’s final brief awakening are skilfully handled, her demise lacks the poignancy of the eponymous hero of Jacob’s Room or of Percival in The Waves. The loss of Rachel provides narrative closure rather than resolution. And yet, this is a key factor of the novel’s Modernity; its refusal to try and make sense out of the senseless.

Woolf had first-hand experience of personal loss. Her mother died when she was thirteen and her father nine years later, after a lingering and difficult illness. Yet, as Claudius reminds us in Hamlet, the death of parents is a common theme in nature: it was the loss of her brother Thoby at twenty-six that left its mark on Virginia’s first book; her glittering, much-admired Cambridge graduate and future barrister brother, whom his adoring contemporaries likened to Johnson and nicknamed “The Goth” for his monolithic qualities. The siblings had travelled to Greece in 1906, where Thoby contracted typhoid fever and returned home to undergo an unsuccessful operation. The shock among his friends was profound. Writing to inform Thoby’s friends of his death, Lytton Strachey felt that “to break it to you is almost beyond my force. You must prepare for something terrible,” and“the loss is too great, and seems to have taken what is best from life.” Walter Lamb, later an unsuccessful suitor of Virginia’s, returned to Hamlet for comfort, stating that Thoby “was likely, had he been put on, to have proved most royal.”

From this disaster, new lives were forged. Two days later, Virginia’s sister Vanessa agreed to marry Thoby’s Cambridge friend Clive Bell. Shortly after their wedding, Virginia began to confide in her new brother-in-law about her “unfortunate” work in progress, then bearing the unusual working title Melymbrosia, which was apparently an invention of Virginia’s. Hesitantly sharing her ambitions to “re-form the novel and capture multitudes of things at present fugitive, enclose the whole and shape infinite strange shapes,” she took Clive’s advice to rewrite passages that were “immature” and “crude” and “jagged like saws that make (his) sensitive parts feel very much what the Christian martyrs must have felt.” Yet he was full of praise for her writing, which was more “beautiful as anything that has been written these hundred years” and left him “stunned and amazed by (her) insight, though… (he) had always believed in it.” The recent publication by Louise de Salvo of a reconstructed version of Melymbrosia bears out some of these points and shows how significant were the changes that Virginia made: no doubt Clive did The Voyage Out a service, if only in allowing its author to sharpen her literary teeth on his bones. He was a fruitful co-parent, but by the time of its completion in 1913, the thought of The Voyage Out’s birth contributed to Virginia’s increasing state of emotional turmoil.

Virginia had married Leonard Woolf in 1912. Their attempts at intimacy were disastrous and quickly abandoned, probably as a result of trauma Virginia suffered as a result of sexual abuse as a young woman. Through 1913, she experienced headaches, sleeplessness, anxiety and loss of appetite: she turned on Leonard and refused to see him, spending part of 1913 in a nursing home. “It is the novel which has broken her up,” wrote her supervisor Jean Thomas, she “thought everyone would jeer at her. Then they did the wrong thing and teased her about it… the marriage brought more good than anything else till the collapse came from the book… it might have come to such a delicate brilliant brain after such an effort.”

Virginia was allowed home that summer but shortly after her first wedding anniversary, she took a potentially fatal overdose of veronal. Her life was saved by the prompt actions of a doctor friend, Geoffrey Keynes, but the road to recovery was a long one. The standard Edwardian response to a suicide attempt was institutionalisation. With her sister considering that Virginia had “worn her brains out,” Leonard made a promise to undertake the necessary care for his wife to prevent her being incarcerated in a home, potentially for life. Without that promise, The Voyage Out might have been the only work by Woolf to make it into print.

It was not until the spring of 1915, that Virginia’s health had recovered sufficiently to allow for the exposure of publication. Lytton had already read The Voyage Out and wrote to assure Virginia that Shakespeare would not have been ashamed of her characters, with the handling of detail being quite “divine.” Most of all, as he was writing his iconoclastic Eminent Victorians, he admired Virginia’s rejection of Victorian values: “I love too, the reigning feeling throughout- perhaps the most important part of any book- the secular sense of it all- 18th century in its absence of folly, but with colour and amusement of modern life as well. Oh it’s very very unvictorian.” Virginia was delighted, replying that he almost gave her courage to read it, which she hadn’t since its publication.

Soon the novel appeared in print, the long-anticipated critical responses began to follow. E.M.Forster’s review appeared in the Daily News and Leader, pleasing Virginia greatly with his comment that “here is a book that achieves unity as surely as Wuthering Heights, though by a different path.” Forster continued: “while written by a woman and presumably from a woman’s point of view, soars straight out of local questionings into the intellectual day” but he made the observation, which Virginia would take seriously, that her characters were not vivid enough. Another reviewer in the Nation praised the novel’s insight but felt the author was too “passionately intent upon vivisection,” inviting Virginia to try again with a second novel but wondering whether it would have many readers. This was balanced by the warmth of Allan Monkhouse’s response in the Manchester Guardian, who recognised that “beauty and significance come with Rachel’s illness and death” which was written with “delicacy and imagination.” He believed that “a writer with such perceptions should be capable of great things.” It was a “remarkable” first novel that showed “not merely promise, but accomplishment.”

Virginia would accept the challenge offered by the Nation. Undaunted, although not unaffected, she would go on to write eight more novels, as well as a proliferation of stories, biographies, essays and non-fiction, beside her many volumes of diaries. The Voyage Out was published to critical acclaim in the United States in 1920, and her mature works, particularly Mrs Dalloway (1925), To The Lighthouse(1927) and The Waves (1931) secured Woolf’s place as a shaper of the Modernist aesthetic. Virginia was always sensitive to criticism, but perhaps not as much as has been suggested: it was the opinions of friends rather than strangers that affected her most deeply. It was not until the final years of her life, overshadowed by the Second World War and fears of personal failure, that the spectre of illness clouded her vision in the same way that it had in 1913. Most remarkable of all is that Woolf’s work remains fresh, challenging and innovative a century after the difficult birth of her career as a novelist. A hundred years after its publication The Voyage Out charts the awakening of consciousness and a grappling with the essential questions of life that is still relevant to a post-modern audience.

My book on Woolf and the Bloomsbury group, "Living in Squares, Loving in Triangles: the Lives and Loves of Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group" will be published by Amberley in May 2015: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Living-Square...

Published on March 16, 2015 06:59

February 11, 2015

An extract from Kristie Dean’s new book “The World of Richard III,” published by Amberley.

“My favourite part of researching this section was actually walking the coronation route. Somehow while tracing Richard’s steps, I stopped seeing the modern city and found myself focusing on the history. At times, I almost expected to see the procession pass me by as it winded its way through the streets”Kristie Dean

Once Richard decided to accept the citizens’ petition and take the crown for himself, he set events in motion that ultimately led to the Battle of Bosworth. From his grand coronation to his death at Bosworth, Richard had a short reign, but he is one of England’s best-known kings.

London: The Coronation

A grand and majestic exhibition, a coronation was an elaborate affair and had been for centuries. Richard has been maligned for his extravagance, but it is fair to state that he was only following in his predecessors’ footsteps. The procession was one stage of the coronation. It allowed the citizens of London to see the king leaving from the Tower. At the head of the coronation train were lords and knights, then the alderman of the city, dressed in vivid scarlet. The newly created Knights of the Bath would follow, along with other members of the train. Directly in front of the king would be the ‘king’s sword’, along with the Earl Marshal of England and the Lord Great Chamberlain.

Tower of London, London. The White Tower rises in the distance in this view across the Thames.

According to Anne Sutton and P. W. Hammond in The Coronation of Richard III: The Extant Documents, the king wore blue cloth of gold with nets under his purple velvet gown, furred with ermine. Four knights carried a silk brocade canopy of red and green above his head. Behind the king rode more lords and knights. The queen, her hair streaming down her back, wore a circlet of gold and pearls on her head and rested on cushions of cloth of gold. She was carried on her litter by two palfreys covered in white damask, with saddles also covered in cloth of gold. Anne, her jewels glistening in the sun, was clothed in damask cloth of gold furred with miniver and garnished with annulets of silver and gold, and was carried under a canopy similar to Richard’s. Following behind the queen’s henchmen and horse of estate came the noble ladies. The women were carried in four-wheeled carts, pulled by horses covered in crimson cloth of gold, crimson velvet and crimson damask, fringed with gold.

Houses along the way would have hung rich tapestries outside their windows. The citizens of London would have lined the procession route, standing on streets that had been cleaned and covered with gravel. The procession was slow as it stopped in Cheapside, at the Standard, the Eleanor Cross and the Little Conduit, along with other stops where stations were set up for speeches and performances in honour of the king and queen. The procession route would havefollowed those of previous coronations and would go through Cheapside, St Paul’s, Ludgate Hill, Fleet Street and then the Strand, ending at Westminster Hall. Here, the king and queen would have been served ‘of the voyde’, which meant they partook of wine and spices beneath the cloths of estate in the Great Hall. Afterwards, the monarchs would have retired to chambers to change clothes and then take an evening meal.

Westminster Abbey, Westminster, London. Richard’s coronation was held within the walls of the great abbey.

In preparation for the joint coronation, a stage would have been set up between the choir and altar at Westminster Abbey. Steps would have led up to the stage on both the west and east sides. St Edward’s Chair, with Scotland’s Stone of Scone underneath, would have sat here for the king, and a richly decorated chair would have been set up on a lower part of the stage for the queen. At the presbytery another pair of chairs would have been set up for the royal couple upon their entry into the abbey.

Early on 6 July 1483, Richard would have arisen, bathed, and then been clothed by his Great Chamberlain, the Duke of Buckingham. Dressed in his white silk shirt, a coat of red sarcenetand silk breeches and stockings, covered by a red floor-length robe of silk and ermines, Richard must have appeared regal. He would have gone to the hall to be raised by nobles into the marble chair of the King’s Bench. Anne would have joined him here. She was dressed in a robe of crimson velvet with a train, kept in place with silk and gold mantle laces, covering her crimson kirtle, which was laced down the front with silver and gilt. Together, they must have looked an imposing pair.

READ THE BOOK TO HEAR ABOUT THE CORONATION SERVICE IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY!

… A lavish feast would conclude the coronation ceremonies for the day. The first course was served on dishes of gold and silver. Beef, mutton, roast, capons, custard, peacocks, and roe deer, along with many other dishes, made up the first course. Richard and Anne entered the hall dressed in fresh robes of crimson velvet embroidered with gold and made their way to the dais.

At the beginning of the second course, Robert Dymoke, as the King’s Champion, came into the hall on a horse trapped in white and red silk. He came riding up before the king and made hisobeisance. The herald asked the assembly, ‘If there be any man who will say against King Richard III why he should not pretend and have the crown’. Everyone was silent, and then in one voice cried, ‘King Richard!’ The King’s Champion threw down his gauntlet three times and then again made his obeisance to the king. After being offered wine, he turned the horse and rode out of the hall with the cup in his right hand as payment for his service. Afterwards, theheralds and four kings of arms came from their stage. The senior herald announced Richard as the King of England and France and Lord of Ireland. The ceremony ended so late that the third course could not be served. Hippocras and wafers were served to the king and queen, and they departed from the hall.

The Author, Kristie Dean.

“The World of Richard III” is available to buy now on Amazon: http://www.amazon.co.uk/World-Richard...

Published on February 11, 2015 10:08

October 26, 2014

Six Wives fly on the Wall: Six Key Moments from Tudor History.

To conclude my blog tour for my new book, “The Six Wives and Many Mistresses of Henry VIII,” I have been thinking about the key moments in the life of each of the six wives. If I were somehow able to travel through time and witness just one moment from the lives of each, these are the events I would choose. All you have to do to be in with a final chance to win a copy of the book is tell me which of these six you would like to have seen, as a fly on the wall. Enter your comment at the bottom of the blog and I’ll announce a winner on Monday November 3. Good Luck.

1. Catherine of Aragon. The Blackfriars Trial, 1529

[image error]

I would have loved to see Catherine’s performance in 1529, when Henry summoned her to defend her marriage. She knelt on the floor before him, argued her case, then swept out of the hall, refusing to return. I think she would have mustered all her strength and experience as a Queen that day and it would have been almost her finest hour, although not her happiest one. It would have been wonderful to have seen the expression on Henry’s face as she spoke.

2. Anne Boleyn. The King’s Hall, Tower of London, 15 May 1536.

[image error]

With all the different moments I could have selected for Anne, again I’ve gone for a sad one, but it is one that would allow me to listen to the evidence that was presented against her and witness her response. I wouldn’t just be watching her though, I’d be looking at all the faces in the room that day, as this process of condemning a Queen was unprecedented and it would be fascinating to see the reactions as her peers and friends lined up against her. We know that her former lover Henry Percy had to leave through “illness”; how many of those men were troubled by their consciences?

3. Jane Seymour. Greenwich, 4 June 1537.

[image error]

Jane made her public debut as Queen less than a week after her marriage, which took place on May 30, 1536. Accompanied by a great train of ladies, she heard mass and dined in public at Greenwich Palace. It was on this occasion that Chapuys reported that she had to be “rescued” by Henry, whilst in discussion with the Ambassador, implying that she was overwhelmed or out of her depth. I would find it interesting to see just how Jane carried herself on this occasion, when she had the standards of Henry’s previous Queens to follow, and what stuff she was really made of.

4. Anne of Cleves. Rochester, 1 January 1540.

[image error]

For Anne of Cleves, it would have to be that fateful moment when she was staying at Rochester overnight on the way to London. Henry arrived in her room unannounced, in disguise, and proceeded to embrace and kiss her. For Anne, it was a breach of dignity, from a large, uncouth man she did not know. Her reaction set Henry against her; it would be amusing to see exactly how she brushed him off, and the resulting embarrassment of the court. This was one dent to Henry’s ego he didn’t recover from.

5. Catherine Howard. Bishop’s Palace, Lincoln, August 1541.

[image error]

At the risk of sounding like a peeping Tom, I would like to have witnessed the illicit meeting between Catherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper that took place on the royal progress of 1541. At the Bishop’s Palace, Lincoln, Lady Rochford helped smuggle Culpeper into Catherine’s chambers late at night via a set of stairs that led to an outside door. They both later claimed that they just talked for hours, and although they desired to consummate their love, had not actually done so. I would really like to know the truth of this secretive relationship.

6. Catherine Parr. The Proposal, 1543.

[image error]

We don’t know exactly where or when Henry proposed to his sixth wife, but it certainly took place in the late spring or early summer of 1543. Catherine, recently widowed, had fallen in love with Thomas Seymour and was hoping to become his wife, when the King intervened, sent Seymour abroad and made his intentions plain. It would have been an incredible moment to witness, as Catherine struggled to reconcile her duty to the loss of her personal happiness. I wonder if she ever really considered the possibility of refusing the King. What exactly did she say to him? I would love to know.

Which of these six moments would you most like to have witnessed? Tell me below.

Published on October 26, 2014 01:01

September 29, 2014

Guest post and Competition: Sara Cockerill's "Eleanor of Castile; The Shadow Queen."

Eleanor and Edward – a summary

extracted from pages 246-247 of “Eleanor of Castile – The Shadow Queen” by Sara Cockerill

[image error] Effigy of Eleanor in Westminster Abbey

The starting point for any consideration of Eleanor’s family must be the most important constituent of it to her – her husband. The more time one spends looking at the life of Eleanor the more apparent it becomes, that she and Edward were genuinely incredibly close, and not really happy out of each other’s company. Marc Morris concludes, and I entirely agree, that their shared tastes for horses, hunting, chivalry, romance and chess had provided a good base for a happy marriage. More than this though, it is fairly clear that they shared a sense of humour – each was plainly ready to laugh and to find fun in amusing pictures and little word plays and both also enjoyed the kind of boisterous fun which marked the coronation. Beyond these shared interests and tendencies, however, one can see in the household records the hallmarks of active respect, consideration and kindness which promote a happy marriage.

[image error] Victorian interpretation of Eleanor

So, repeatedly each can be seen paying attention to the interests of the other, and doing their best to help. Each helped the other financially – Eleanor gifting Edward with 1,000 marks when he and everyone else was out of cash following the Gascon expedition, and Edward helping with purchase monies and funds for improvements for her properties. For Eleanor, Edward was the centre of her world, and she identified herself completely with his interests – as she had been raised to do. Everything gave way to his interests and she would uproot herself from her work for years at a time to be with him in Wales and in Gascony, as well as on crusade. Although Eleanor had her own office and powerbase of very able employees, there was no “Team Queen” operating in opposition to “Team King”; unlike the position under Eleanor of Provence and Henry III. Eleanor and her staff were parts of Edward’s team, and never sought to be perceived otherwise. But it was far from being a one way street. Having charged Eleanor with a role in property management, Edward was supportive of Eleanor’s very active interest in this role; to the extent of inconveniencing himself in repeated dislocations.

[image error] Edward I (not contemporary)

Each can also be spotted in the records planning pleasant surprises for the other, and trying generally to make life more pleasant for their spouse. So in Gascony, Eleanor sent home to get Edward a particularly special hunting bird for his birthday, while on another occasion Edward, mindful of Eleanor’s book obsession and vibrant theological interests, commissioned a psalter and book of hours as a present for her. Facing a social engagement too far, Eleanor agreed to go by herself, and made arrangements for musicians to be hired to amuse Edward, while she was discharging their social obligations. Meanwhile, Edward made sure that everywhere they went, gardeners and decorators went ahead, so that Eleanor need not face the shabby lodgings which were her aversion.

One surprising thing which emerges from the record is that Edward was surprisingly sentimental – rather more so, it would appear, than Eleanor. So the records of his charitable oblations for 1283-4 show him giving extra alms on the occasion of their wedding anniversary and also in those nervous days in the run up to Eleanor giving birth to Edward, as well as the expected celebratory donations on the birth and christening of a prince. When Eleanor was ill and he could not actually be with her, he sent thoughtful gifts of food, with which he hoped to tempt her appetite or recoup her strength. The public face of his mourning is well known, but in addition to the well-known gestures after Eleanor’s death of commissioning spectacular funeral monuments he provided chantries at the place of her death, and at Leeds castle where they had spent happy time together. He also took for himself the chess set with which they had played chess together.

You can win an copy of Sara Cockerill’s new book “Eleanor of Castile: The Shadow Queen,” by leaving a comment at the bottom of this blog post. Good luck.

[image error]

Alternatively, buy a copy from Amazon here: http://www.amazon.co.uk/Sara-Cockerill/e/B00NGG5QRC/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1

Published on September 29, 2014 01:27

September 16, 2014

No place for an Edwardian Lady: New Women and Old Art.

No place for an Edwardian Lady: New Women and Old Art.

[image error]

The Slade "crop-heads:" Dora Carrington, Barbara Baegnal and Dorothy Brett.

In 1910, a young woman nervously carried a portfolio of sketches up to the doors of the Slade School of Art. She was twenty-six, dressed in the heavy long trumpet skirts and billowing blouses of Edwardian fashion, with her long dark hair pinned up and her eyes cast modestly down. The daughter of Viscount Esher had spent a sheltered childhood in Mayfair, sharing dance classes with Queen Victoria’s children. Educated to be launched in polite society, she had loathed the limited education she received at the hands of governesses and, according to her sister, used to throw candlesticks at her unfortunate instructresses.

Her eyes were not unintelligent but her cheeks, full with the flush of youth and her parted lips, along with her slight deafness, gave her a rather startled expression as the omnibuses rushed past her along the Euston Road. Yet behind that surprise was a steely determination. For a decade she had fought against her father’s resistance, pleading and persuading to be allowed to attend art school, long past the age when most of her contemporaries were married with children. Finally, friends had intervened and helped changed the Viscount’s mind. With the paternal obstacle overcome, Dorothy Brett now had to prove her abilities to the world. As she later said, “I’m a woman and therefore I’ve got to force myself on people; a young man is watched by collectors to see if he is a clever student… society women are on the lookout for him and get him in tow if they can and buy a few a few works and keep him alive… None of this happens to a girl.” But this girl was one of a growing breed of Edwardian women who turned their back on contemporary notions of female duty and carved out a more Bohemian path.