M.R. Dowsing's Blog

September 7, 2025

Jakoman and Tetsu / ジャコ万と鉄 (1949)

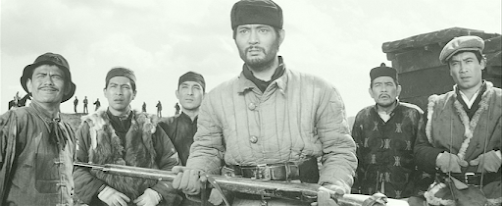

Toshiro Mifune and Kamatari Fujiwara

Toshiro Mifune and Kamatari Fujiwara

Kyubei (Eitaro Shindo, better known as Sansho the Bailiff) has a herring-fishing business in Hokkaido andis anticipating the annual arrival of the fish when his son, Tetsu (ToshiroMifune) – presumed missing in the war – unexpectedly turns up. Tetsu issurprised to find that one of the fishermen employed by his father just liesaround all day drinking saké and refusing to work. The man in question is Jakoman(Ryunosuke Tsukigata), an aggressive individual with an eye-patch whom everyoneis afraid of and who has a beef with Kyubei because Kyubei stole his boat toescape from Sakhalin island when the Japanese were chased out by the Russiansat the end of the war.

Meanwhile, a woman named Yuki (Yuriko Hamada) turns up in searchof Jakoman, and it emerges that she’s in love with him despite the fact that hewants nothing to do with her and treats her roughly. In the midst of all thispersonal drama, the herring finally appear just as the men call a strike due tolow pay…

This Toho production* was based on a 1947 novel entitled Nishin ryoba (‘Herring Fishing Grounds’)by Tokuzo Kajino (1901-84, sometimes incorrectly listed as ‘Keizo Kajino’ or‘Shinzo Kajino’). The screenplay was co-written by the director, SenkichiTaniguchi, and Akira Kurosawa, with whom Taniguchi frequently collaborated duringthis stage in their careers, and its full of characteristic Kurosawa touches. Onesuch is when Kyubei’s son-in-law (Kurosawa favourite Kamatari Fujiwara), anapparently slow-witted clerk given to hiccups and sneezing, plays the shakuhachi (bamboo flute) and moveseveryone to tears, instantly clearing up the mystery of what his wife (NijikoKiyokawa) sees in him. Indeed, the script seems to have been largely the workof Kurosawa, with Taniguchi making some changes when he came aboard asdirector, and Kurosawa apparently brought the characters of Jakoman and Tetsuto the fore for the film, whereas the source novel had Kyubei as its mainprotagonist. Concerning Taniguchi, it’shard to take him very seriously as a director given the hokum that he made inthe final years of his career, while the fact that so many of his other films are basicallyinaccessible means that he’s likely to be forever regarded as a footnote toKurosawa (who was said to have done much of the editing on Taniguchi’s earlyfilms).

Mifune – who has to perform a spectacularly weird song and dancewhich I bet embarrassed him – looks great and is effortlessly likeable asTetsu, while Ryunosuke Tsukigata is almost too convincing as the villainousJakoman, his one eye glinting with concentrated malevolence. Tsukigata hadpreviously played two of the opponents in Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata films and has a staggering 499 credits on theJapanese Movie Database. The female lead, Yuriko Hamada, also makes a strongimpression even if her feisty character is tamed at the end. (Hamada’s fateremains a mystery – she made her final film in 1957 and nobody seems to knowwhat happened to her after that.) Excellent use of locations and a fine scoreby Godzilla composer Akira Ifukubealso help to make this an enjoyable watch. The main flaw of the film is that itlacks subtlety in the way it puts across its rather obvious moral message.

In regard to Kinji Fukasaku’s 1964 remake, while it was a goodidea to replace the original film’s subplot of Tetsu falling in love with agirl he sees playing the organ in a Christian church** (played by an almostunrecognisably young Yoshiko Kuga) with one in which he falls in love with thesister of a deceased comrade whose family he visits, in my opinion that was theonly thing that the remake did right. Aside from that, everything that was goodabout the first film has evaporated in Fukasaku’s tedious version, which seemsto have been a vanity project initiated by its star, Ken Takakura. Unfortunately,that’s the one which is available in a very nice limited Blu-Ray from 88 Films.

The original film was abox office success and spawned a sequel entitles Jiruba Tetsu (1950) again starring Mifune, Yuriko Hamada and EitaroShindo and co-written by Kurosawa but directed by Isamu Kosugi and produced byTokyo Eiga.

*Actually, although itwas distributed by Toho and bears the Toho logo at the beginning, the followingtitle card announces the film as a ’49 Years production’. It seems to be theonly film credited thus, something which appears to be a result of the labourdispute that was going on at Toho at the time. Perhaps the strike called by themen in the film was partly a comment on the situation, but though the fishermen settletheir differences with Kyubei, that was sadly not to be the case at the studio.

**According to ‘I LoveJakoman’ on Amazon Japan,

…it was Taniguchi's idea for Tetsu to fall in love with the church girl, andupon hearing it, Akira Kurosawa reportedly remarked, "That stinks."(Taniguchi himself said this at a Taniguchi Film Screening).

Only Kurosawa andTaniguchi are credited with the screenplay for the 1964 remake, but it’sunclear whether either had any involvement in the changes made.

Watched without subtitles

September 3, 2025

Rise, Fair Sun / 朝やけの詩 / Asayake no uta (‘Poem of the Morning Glow’, 1973)

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya Nakadai

The Shinano Plateau,Nagano. Left without a position after Japan’s defeat, former naval officer Sakuzo(Tatsuya Nakadai) is now a comparatively poor but hard-working and extremelyproud farmer with a teenage daughter, Haruko (Keiko Takahashi), and two youngerchildren, all of whom he is raising by himself. His wife, Yaeko (KanekoIwasaki), seems to have been unable to bear the drudgery, has developed a drinkingproblem and left him for an easier life, shacking up with Kamiyama (YosukeKondo). He’s the president of Apollo Tourism, who want all the farmers in thearea to clear out so they can use the land to build a holiday resort. As thefarmers are all in debt to local bigwig Inagi (Shin Saburi), Kamiyama conspireswith him to make them an offer they can’t refuse, but some – like Sakuzo –prove inconveniently stubborn. When land surveyors are sent in, violence breaksout…

Kaneko Iwasaki and Keiko Takahashi

Kaneko Iwasaki and Keiko TakahashiRise,Fair Sunwas a co-production between Toho and Haiyuza, the theatre company to whomNakadai and a number of his fellow cast members (including Kaneko Iwasaki andYosuke Kondo) belonged. The film was directed by Kei Kumai and based on hisoriginal screenplay, co-written with the little-known Akiko Katsura and theslightly better-known Hisashi Yamanouchi, who had worked on three of ShoheiImamura’s early pictures. Like many of Kumai’s films, it has an obviousleft-wing, social conscience theme.

Shin Saburi and Nakadai

Shin Saburi and NakadaiIn the early 1970s,many Japanese feature films returned to using the old academy ratio that thestudios had originally abandoned around 1957, and this film is one example of such. As I understand it, this was mainly done because it was cheaper and thestudios’ profits were diminishing, but I also wonder whether it may have beenrelated to the more TV-friendly nature of the academy ratio as the sale offilms to television after their cinema run was more of a concern by this point.In any case, it’s part of the reason why Rise,Fair Sun has something of a TV miniseries feel to it. However, that’s notto say that the film fails to impress visually – mostly shot on location, itfeatures some beautiful scenery and attractive cinematography by Kozo Okazaki (Goyokin, Inn of Evil) which includes a spectacular shot of Haruko and heryoung lover silhouetted against the sun towards the end. Another plus is the scoreby Kumai’s regular composer, Teizo Matsumura, which is refreshingly free fromthe usual clichés.

The film is generallyvery sympathetic to Sakuzo despite the clear suggestion that his wife has beena victim of domestic violence, an implied additional motivation for herabsence. Like Toshiro Mifune in Redbeard,there’s a scene in which Nakadai appears to forget that he’s not in a samuraimovie and launches a one-man attack on multiple opponents – in this casegrabbing a surveying pole and going into full Sword of Doom mode on the unfortunate surveyors. As if tocompensate for this violent side, he tries to save a bloated cow (by stabbingit!) and, while digging on his land, he discovers an ancient pot from the Jomonpeople (who were believed to have lived in harmony with nature to a remarkabledegree). This instantly turns his farm into a major archaeological site, andwhen a Jomon face sculpture is dug up, he declares it better than anything in theLouvre (which he has apparently visited while in the navy). This unexpectedplot thread is quickly dropped, but – with symbolism not too hard to decipher –we will later see a shot of a bulldozer carelessly running over another pieceof Jomon pottery.

The film marked veteranstar Shin Saburi’s return to the big screen after an absence of 12 years,during which time he had been very active as both an actor and director intelevision. It was his first film opposite Nakadai and there’s a memorableconfrontation scene between the two, who were reunited the following year inSatsuo Yamamoto’s The Family. Nakadaihad known his other co-star, Kaneko Iwasaki, since the very beginning of hisacting career and the two had appeared in a number of films together. Thoughshe has seldom had leading roles in feature films, Iwasaki is the officialrepresentative of Haiyuza at the time of writing and remains a highly respectedstage actor who played the King Lear equivalent in Haiyuza’s 2024 production Dokoku no Ria (‘Lear’s Lament’).

The production of thefilm was overshadowed by the publicity around the nude swimming scene featuringan 18-year-old Keiko Takahashi – then known as Keiko Sekine – who had alreadybeen a popular star for a couple of years at this point. Although the inclusionof such a scene may have been a cynical move by the producers, it wastastefully shot by Kumai, but in any case it was not enough to make Rise, Fair Sun a hit either at the box office or with the critics. Though screened in competition at the Berlin Film Festival, it failed to win anyprizes. This is not too surprising as, despite some good work in a number ofdepartments, it’s basically a noble effort which doesn’t quite gel – mainly, Ithink, due to the flawed script and somehow unconvincing characters. In my view,stories of this type often work better with a more Ken Loach-type approach, inwhich the use of improvisation by a cast of mainly non-professionals can be more effective.

The Berkeley Art Museumand Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) Film Library in Californiaa has a 35mm print of this film with English subtitles

Thanks to A.K.

August 29, 2025

Ten no yugao / 天の夕顔 (‘A Moonflower in Heaven,’ 1948)

Mieko Takamine

Mieko Takamine

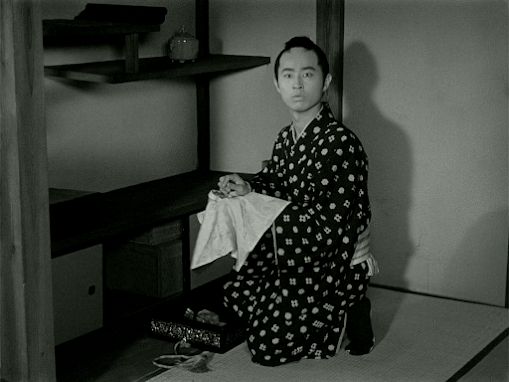

Toyohiko Fujikawa

Toyohiko FujikawaTatsunoguchi (Toyohiko Fujikawa) is a recluse who lives in a huton a snowy mountain and shoots rabbits for his dinner. One day when outhunting, he notices a man (Haruo Tanaka) lying in the snow. The man is stillalive and asks Tatsunoguchi to leave him there, but he takes him to his hut andnurses him back to health. It emerges that the man had wanted to die due to a loveaffair that went wrong, so Tatsunoguchi begins to tell him his own story of howhe ended up living in such isolation.

As a student, every Friday Tatsunoguchi had passed a young woman,Akiko (Mieko Takamine), on his way to university and gradually fallen in lovewith her. However, the encounters suddenly ceased and, when he did finally runinto her again three years later, she had already acquired both a husband and an infant son, although her marriage was a failure. Akiko reciprocated Tatsunoguchi’s feelings,so their love continued to grow, resulting in an on-and-off relationship thatcould only ever be platonic dragging on for years and leading to Tatsunoguchi's eventualself-exile to the mountain…

This Shintoho production was based on a 1938 novel of the samename by Yoichi Nakagawa (1897-1994) and is the only film adaptation of his workto date. According to Japanese Wikipedia, the novel ‘garneredhigh praise in Western Europe as a masterpiece of romantic literature, comparable to Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther. After the war, it was translatedinto six languages, including English, French, German, and Chinese, and washighly praised by Albert Camus.’ We also learn thatNakagawa got the story upon which he based his book from a masseur namedKozaburo Fujiki, who greatly resented the fact that Nakagawa refused to givehim any credit. A feud between the two men lasted for decades, culminating inthe self-publication of a 1976 book by Fujiki with the splendid title The Great Achievement of Shattering the Masterpiece Ten no yugao - A Guide for Reading Novels Carefully andwith Taste.

This literary feud isarguably more entertaining than the film itself, which is an extremely maudlinpiece of work, an aspect emphasized by the keening violin featuredexcessively throughout composer FumioHayasaka’s score. Director Yutaka Abe had already made around 60 films at thispoint, and went on to make The MakiokaSisters (1950) and Confession(1956). He certainly does a competent job, but the material is so old-fashionedand sentimental that it has dated very badly indeed and is at times evenlaughable today - the animated firework near the end being an especially corny touch.

Leading lady MiekoTakamine will be familiar to many readers, but who, you may well wonder, was herco-star, Toyohiko Fujikawa? Well, he seems to havebeen born in 1924 and has just two other credits, both in Daiei movies from1950. According to @Shimo_x2on x.com, he ‘was not originally an actor but a young president of aconstruction company. It seems he also invested in this film, making hisappearance in the movie something of a hobby.’ In any case, he gives a slightlystolid but perfectly acceptable performance and certainly looks the part of aleading man.

This film appears to lack an official English title, but is sometimeslisted as ‘The Beauty of the Evening Sky.’ However, the first kanji can beinterpreted as ‘heaven’ as well as ‘sky’ and, while夕on its own means ‘evening’ and 顔 can mean ‘face’ (but not ‘beauty’), the final twotogether mean ‘moonflower’, and there is in fact a scene in which MiekoTakamine admires a moonflower (ipomoeaalba), which bloom at dusk and last only for one night. The Englishtranslation of the book by Akira Ota published by The Hokuseido Press in 1949is also titled A Moonflower in Heaven.The cover art is by Jean Cocteau.

Watched with dodgy subtitles.

August 26, 2025

Izu no odoriko / 伊豆の踊子 (‘The Dancing Girl of Izu’, 1954)

Hibari Misora

Hibari Misora

ThisShochiku production was the second film version of a famous short story byfuture Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata (1899-1972). First published in1926, it's a semi-autobiographical piece based on a solitary walking trip hetook as a student around the Izu Peninsula in the year 1918. Attracted to ayoung dancer who is part of a small group of travelling entertainers, thenarrator (named Mizuhara in the film) contrives to fall in with them. The othersare Eikichi, a man of 23 who is the leader; his 18-year-old wife Chiyoko; hermother; and Chiyoko’s 16-year-old sister, Yuriko. The dancer, named Kaoru, is Chiyoko’s youngestsister. Although disconcerted to find that she is only 13 (he had judged her tobe 15-16*), he finds himself deeply moved at the group’s friendliness towardshim, and this greatly helps to mitigate his low self-esteem.

Whilethe story is often characterised as one of unrequited youthful love, there’smore to it than that. Like Kawabata, the narrator/Mizuhara is an orphan with noclose family left alive, and Kawabata is said to have been concerned as a youngman that this fact may in some way warp his personality. Despite the extremelylow status of travelling entertainers in Japanese society at the time, thefamily in the story are not unhappy and enjoy a warm relationship with oneanother. It’s clear that the narrator is pathetically grateful to be accepted –almost adopted – by these outcasts, and this aspect of the work is equally asimportant as the theme of young love.

Evenin its unabridged form, Kawabata’s story is not really long enough to sustain afeature-length film, so screenwriter Akira Fushimi expanded it, mainly by giving the family ofentertainers a more detailed backstory, introducing a rival for Kaoru’s loveand adding a minor sub-plot about a young boy pursuing Mizuhara from villageto village to return some money he had dropped. Incidentally, it was Fushimiwho had also written the screenplay for the first adaptation, a silent filmmade by Heinosuke Gosho in 1933. However, for this one he wrote a fresh scriptwith a number of differences, the most notable being that the character ofEikichi is far more sympathetic in the second version, in which he is played byAkihiko Katayama. This is more faithful to Kawabata.

Thesilent version had starred a 22-year-old Kinuyo Tanaka alongside the26-year-old Den Ohinata, whereas this one stars 16-year-old Hibari Misora asKaoru and 19-year-old Akira Ishihama as Mizuhara. Misora was best-known for hersinging ability, but gets surprisingly few opportunities to sing here, whileIshihama will be familiar to many as the young samurai forced to commit seppuku with a bamboo sword in Harakiri (1962). Although these twoactors are the right age for their characters, I felt that their actingabilities were a little too limited to really put across their feelings asdescribed by Kawabata, but director Yoshitaro Nomura is also partly to blamefor this. Compare the final scene on the boat with what Kawabata had writtenand you’ll probably see what I mean. Here’s what Kawabata wrote (as translatedby J. Martin Holman):

I lay down, using my bag as apillow. My head felt empty, and I had no sense of time. My tears spilled onto my bag. My cheekswere so cold I turned my bag over. There was a boy lying next to me. He was theson of a factory owner in Kawazu and was on his way to Tokyo to prepare toenter school. The sight of me in my First Upper School cap seemed to elicit hisgoodwill.

After we talked for a while, heasked, "Have you had a death in your family?"

"No, I just leftsomeone."

I spoke meekly: I did not mindthat he had seen me crying. I was not thinking about anything. I simply felt asthough I were sleeping quietly, soothed and contented.

I was not aware that darkness hadsettled on the ocean, but now lights glimmered on the shores of Ajiro andAtami. My skin was chilled and my stomach empty. The boy took out some sushiwrapped in bamboo leaves. I ate his food, forgetting it belonged to someoneelse. Then I nestled inside his school coat. I felt a lovely hollow sensation,as if I could accept any sort of kindness and it would be only right. […]

The lamp in the cabin went out.The smell of the tide and the fresh fish loaded in the hold grew stronger. In thedarkness, warmed by the boy beside me, I let my tears flow unrestrained. Myhead had become clear water, dripping away drop by drop. It was a sweet, pleasantfeeling, as though nothing would remain.

Butin the film, Ishihama can barely manage a single tear and Nomura decides to endit with a shot of Misora staring blankly at the water, followed by a shot of asingle geta (wooden sandal) floatingoff. Personally, I felt that Nomura had rather missed the point of the endingand also not shot what he did as effectively as he could have – a shame, as otherparts of the film are a good deal more impressive.

Afterthe success of his 1958 film Stakeout,Yoshitaro Nomura became best-known for his intelligent and twisty crime dramas,often based on Seicho Matsumoto stories, and films from this earlier stage inhis career are not easy to see. The nature of the story meant that the bulk ofit had to be shot on location, and this is something that Nomura seemed torelish. Despite his odd lack of focus (for the most part) on the emotions ofthe two main characters and the performances of the two leads, he was atalented filmmaker and this is most obvious in a sequence which occurs around21 minutes in, contains no dialogue and lasts for just under three minutes. Itsimply features Mizuhara walking by himself during a heavy rain shower andpausing to take shelter in a doorway, through which he watches a baby cryingalone until a boy (presumably the baby’s older brother) runs up and stares athim, at which point he hurries on. There’s a sense that even the crying baby isbetter off than Mizuhara because at least it has a big brother to look afterit. This beautiful sequence does nothing to advance the plot but expressesMizuhara’s loneliness perfectly without even requiring Ishihama to do much inthe way of acting. Most of the film and this scene in particular are alsohelped by Chuji Kinoshita’s restrained score – one of his better ones, with theexception of his use of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ at the end, which can’t help but feelcorny. Anyway, despite my quibbles, this film is well worth seeking out and quite likely the best film version of the story to date.

*Othersources may give different ages depending on which age system is used, and thetwo translations of the story intoEnglish do not agree. The first, by Edward Seidensticker, appeared in 1954, wasslightly abridged, and described Kaoru as being dressed and made-up to appear15 or 16, but turning out to be only 13. The second translation, by J. MartinHolman, appeared in 1997, was unabridged, and described Kaoru as looking 17 or18 but actually being 14. The discrepancy is due to the fact that Seidenstickerused the standard system of counting age in the West, whereas Holman used thetraditional Japanese system, which considered a person to be one year old atbirth and for their age to increase by a year not on their birthday, but at theturning of the New Year. This system is no longer used in Japan.

Thanks to A.K.

August 22, 2025

Arijigoku sakusen / 蟻地獄作戦 / (‘Operation Antlion’, 1964)

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya Nakadai

This Toho production was the fourth entry in their ‘Sakusen’(‘Operation’) series, which attempted to emulate the style of Kihachi Okamoto’s1959 hit Desperado Outpost and itssequel (in fact, it’s sometimes considered the sixth film in the Desperado Outpost series). These filmshad brought a new cynicism and humour to the war action genre in Japan andfound favour with males of the younger generation, for whom the more po-facedwar films were often a turn-off.

This one stars Tatsuya Nakadai – who had actually been offered thelead in Desperado Outpost but beenobliged to turn it down due to his commitment to The Human Condition. This turned out to be a stroke of luck forMakoto Sato, who was cast in his place and went on to star in all of thefollow-ups. However, in this film he plays second banana to Nakadai, apparentlybecause Toho wanted to try increasing the audience numbers by giving the leadto an actor with a lot of female fans.

L-R: Natsuki, Hirata, Sato, TN, Sakai,

L-R: Natsuki, Hirata, Sato, TN, Sakai,

Nakadai plays Lt. Isshiki, an insubordinate junior officerassigned with a suicide mission to blow up a bridge somewhere in China duringthe final months of the war. He’s given a team of five other insubordinatetypes, several of whom are released from the stockade for the purpose. Theother men are played by Makoto Sato, Yosuke Natsuki, Sachio Sakai, AkihikoHirata (the one-eyed scientist in the original Godzilla) and Tadao Nakamaru. Naturally, this dirty half-dozen encountera variety of dangers on their way to the bridge and mow down a large number ofunfortunate Chinese National Revolutionary Army fighters in the process. Ofcourse, it’s one thing watching soldiers of the Allied Forces machine-gunningNazis and quite another when it’s Japanese soldiers doing it to the Chinese,which makes this film and its ilk a little problematic. The filmmakers throw ina couple of ‘good’ Chinese characters, but neither are convincing. One is anapparently cowardly villager played by Kan Yanagiya who turns out to be aresistance fighter, while the other is a grimy-faced ‘boy’ who looks exactlylike a young woman and turns out to be (surprise, surprise) a young woman.Played by Kumi Mizuno, she falls in love with one of the Japanese soldiersafter he gives her a rice ball. Still, if its gritty realism you’re after,you’re watching the wrong film as this is strictly entertainment and, to befair, it succeeds pretty well on that level even if much of the humour was toobroad for my taste.

The film moves along at a good pace and is very well staged andshot by director Takashi Tsuboshima and his cinematographer Fukuzo Koizumi (whoalso shot Kurosawa’s Sanjuro).Tsuboshima had worked as an assistant to Jun Fukuda, who was best-known for hismonster movies, and he was probably not the best with actors – allowing toomany of the supporting cast to go way over the top here – but clearly had agreat deal of technical skill. Although his output was largely routine, helater made the interesting Bonds of Love(1969).

Nakadai looks like he’s enjoying himself in a more straightforwardaction role than he usually played, and does plenty of horse-riding andshooting, but there’s nothing to stretch him here. Although the movie pre-datesThe Dirty Dozen (1967), the influenceof English-language war films (especially TheGuns of Navarone) and westerns is obvious. Toho’s DVD release boastsperfect picture quality and the film is not too difficult to follow evenwithout subtitles as the plot mostly consists of men-on-a-mission clichés anyway.

A note on the title:

As far as I’m aware, the film has not beendistributed in any English-speaking countries and has no official Englishtitle. IMDb and some other sites list it as‘Jigoku sakusen’, but that title gives only the last four kanji in romanji. The first kanji, 蟻, means ‘ant’, while the second and third togethermean ‘hell’ and the final two (‘sakusen’) in combination can mean ‘tactics’, ‘strategy’ or ‘military operation’. Letterboxd lists the film as ‘Ant Hell War’. However, although a literaltranslation of the first three kanji gives ‘ant hell’, it’s actually the Japanese name for ‘antlion’. Wikipedia offers the followinginformation:

The antlions are a group of about 2,000 species of insect in th neuropteran family Myrmeleontidae. They are known for the predatory habits of their larvae, which mostly dig pits to trap passing ants or other prey.

In Japan, both the insect and its pit-traps are popularly known as Arijigoku (蟻地獄; lit. "Ant Hell"). This term has since become a stock colloquialism for any "inescapable" trap, whether literal or metaphorical (e.g. an unpleasant social obligation).

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antli...

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Antli...

DVD at Amazon Japan (no subtitles)

August 18, 2025

Yume miru hitobito / 夢見る人々 (‘People Who Dream’, 1953)

Yoko Katsuragi

Yoko Katsuragi Shinya (Masao Wakahara)is an architect who returns home from ‘the South’ for the first time since thewar to find that his fiancée, writer Yuriko (Mieko Takamine) has marriedsomeone else, his family home has been destroyed in an air raid and his parentskilled, and his half-sister and her husband have spent his inheritance.Needless to say, he’s not a happy bunny. However, his father’s friend’s granddaughter,Sumiko (Yoko Katsuragi), still loves him even though he only thinks of her as ayounger sister…

Masao Wakahara

Masao WakaharaThis Shochiku productionwas based on a 1952 newspaper-serial novel by Nobuko Yoshiya, theChristian-lesbian writer who also supplied the source material for Flower-Picking Diary (1939). In thiscase there’s no sign of Christianity nor lesbian love, and the two moreunconventional female characters – company president Fujie (Sadako Sawamura)and her tomboyish daughter Ioko (Kyoko Kami) – seem to be present mainly toserve as comedy relief. Speaking of comedy, one amusing moment which feelsunintentional comes at the beginning when a blind war veteran solicitsdonations on a train and seems able to tell when people are holding out moneyto him even when they say nothing.

Kyoko Kami, Wakahara and Sadako Sawamura

Kyoko Kami, Wakahara and Sadako SawamuraThe awkward subject ofthe war is always present in the background of the story, but only occasionallycomes to the fore, and it’s entirely unclear what Shinya has been doing for theseven or eight years since the conflict ended. We know only that he hastestified on behalf of a former sergeant, Arakawa (Jun Tatara), to save himfrom being sentenced as a war criminal. Many of the characters are portrayed asvictims of the war in various ways, and there’s never really an acknowledgementof any guilt – the closest we get is a scene in which Shinya’s father’s friend,Shibata (Eijiro Yanagi), finally forgives his son, who had incurred his wrath during the war by daring to express the opinion that Japan would lose.

Mieko Takamine

Mieko TakamineIn terms of the cast,the forgotten Masao Wakahara as Shinya – described at one point as looking‘like (Charles) Boyer’ – seems to have been quite a big star at the time, buthis performance here is on the wooden side, which is perhaps why his career peteredout early once his Boyer-esque looks began to fade. Mieko Takamine does herbest with an underwritten role, but it’s Yoko Katsuragi as Sumiko who reallybecomes the heart of the film. She was an underrated actor whose girlish looksoften prevented her from getting the more interesting dramatic parts, but it’s notfor nothing that she was a favourite of Keisuke Kinoshita as well as thisfilm’s director, Noboru Nakamura, for whom she made six pictures. One of thesewas Nakamura’s previous film, Natsuko’s Adventure in Hokkaido, in which she had also co-starred with Masao Wakahara. Regarding Nakamura,his direction is certainly highly competent, but his best work was yet to comein films such as Koto (1963), The Shape of Night (1964) and The Kii River (1966).

Thanks to A.K.

August 14, 2025

The School of Flesh / 肉体の学校 / Nikutai no gakko (1965)

Kyoko Kishida

Kyoko KishidaTaeko(Kyoko ‘Woman of the Dunes’ Kishida) is a wealthy, aristocratic and self-confidentTokyo fashion designer who visits a gay bar, where she is attracted to younger,proletarian bartender Senkichi (Tsutomu Yamazaki, the kidnapper from High and Low), whom she asks out on adate. The rumour that he’ll sleep with absolutely anyone for money fails to puther off, but she’s taken aback when he turns up wearing geta (wooden sandals), chews with his mouth open and takes her to apachinko parlour, but she soon gets over it and the two embark on arelationship. However, when her friends ask her if Senkichi is kind to her, sherealises that she can’t think of a single example of his showing such a qualityand begins to feel somewhat insecure in their relationship. But it turns outthat Senkichi is actually far more conventional than he pretends to be…

Tsutomu Yamazaki

Tsutomu YamazakiThisToho production was based on a novel of the same name by Yukio Mishima first published in 1963 in serial form in a magazine called Mademoiselle. Although it has yet to betranslated into English,* this appears to be a very faithful adaptation andMishima is on record as being highly pleased with it. The author’s obsessionwith physical beauty and the psychology of infatuation are much in evidence,but theprotagonists are both hard to like and I can’t say that I personally found the story very engaging. Most of the drama comes from the shiftingbalance of power in their relationship.

Whatreally makes this film worth seeing, however, is the striking visual style thatdirector Ryo Kinoshita (b.1931) and his cameraman Yuzuru Aizawa (who also shot The Bad Sleep Well) bring to it. Kinoshitawas a former assistant to Yuzu Kawashima (and no relation to Keisuke Kinoshitaas far as I’m aware). The rest of his brief filmography looks pretty routine, buthe was one of those directors whose career began a little too late, leaving himfew opportunities to show what he could do for the cinema before he was forcedto move into television instead. In fact, part of the reason for the move inhis case may have been that the bigwigs at Toho were, apparently, displeasedwith the arty visuals in The School ofFlesh. However, in my opinion, the use of deep focus, unusual camera anglesand bold lighting effects makes this film a visual treat throughout.

The agediscrepancy between the two characters is less pronounced than in the book,which describes Taeko as being 39 and Senkichi 21 – at the time of the film’srelease, Kishida was 34 and Yamazaki 28. The two stars had both been members ofthe Bungakuza theatre company and knew each other well. Another personassociated with Bungakuza was Yukio Mishima himself – the company had staged anumber of his plays, often featuring Kishida, an actress who was both admiredand befriended by the writer.

*Thenovel has appeared in French and also provided the basis for the French film L’ecole de la chair (1998) starringIsabelle Huppert.

Thanksto A.K.

August 11, 2025

Flower-Picking Diary / 花つみ日記 / Hana-tsumi nikki (1939)

Hideko Takamine

Hideko TakamineMitsuru (MisakoShimizu) is a girl from Tokyo whose family have just moved to the Soemonchodistrict of Osaka. She’s in her early-mid teens and her mother is a Christian. Whenshe begins attending her new school, she soon becomes best-friends with classmateEiko (Hideko Takamine), who used to live in Tokyo herself when she was small.Her family have a business training maiko(apprentice geisha) to sing, dance and play instruments. When the two girlscome up with a plan to make a gift together with which to surprise their kindlyteacher (Kuniko Ashihara) on her birthday, a misunderstanding ensues and theyfall out. Both girls are miserable as a result, and Eiko gets to the pointwhere she can’t even face school anymore, so she drops out to become a maiko herself…

Produced by Toho Eigabefore they became known simply as Toho from 1943, Flower-Picking Diary was based on a story by Nobuko Yoshiya(1896-1973). Being both a Christian and a lesbian, she wrote from an unusualperspective for a Japanese author of the time, but her books were highlypopular with female students – so much so, in fact, that there had already beenaround 30 movies based on her work. The main source of this particular pictureis a story entitled ‘Tengoku to maiko’ (‘Heaven and maiko’) from her 1936 collection Chisana hanabana (LittleFlowers), but it seems that some elements may have been borrowed from otherstories by Yoshiya as the story of the film (as adapted by female screenwriterNoriko Suzuki) differs considerably. The main difference is that there isapparently no falling out between the two girls in the original – a fact Ifound quite surprising considering that this is absolutely central to the film.Indeed, the extent to which it should be interpreted as the story of a lesbianlove is debatable – there’s certainlynothing overt – but it’s certainly a film about friendship and the devastatingfeelings that can occur when two close friends fall out. It’s difficult tothink of other examples of films dealing seriously with broken friendships, butthis one is very moving once it gets going (there may be rather too muchsinging of sentimental songs in the earlier stages).

The shadow of war loomslarge over the film, and the scenes of largely unquestioning and joyfulcelebration when Mitsuru’s brother gets called up have not dated well, but arerevealing of their time. (Incidentally, Nobuko Yoshiya’s reputation suffered somewhat afterthe war as she was said to have toed the authoritarian government line a littlemore than necessary.) Ironically, though, it’s the war that gives some hope forthe future of Eiko and Mitsuru’s friendship as Eiko decides to make a senninbari for Mitsuru’s brother, whichinvolves her standing at the bridge on Shinsaibashi Street and asking passingwomen to sew a stitch to make up the 1000 needed for this type of amulet belt.

Hideko Takamine was 15when she made this, but already an old pro who had made dozens of films sinceher film debut in 1929 at the age of 5. Her co-star, Misako Shimazu, was a veryyoung-looking 20 years of age, and was featured in a few other films butdisappeared from the screen after 1941. Takamine may well have related to herrole more than usual here as, shortly before making the film, like Eiko, she hadbeen forced to leave school and pursue a career she did not particularly carefor (acting in movies was something she felt obliged to do as no less than ninefamily members were relying on her financially).

The sensitive directionis by Tamizo Ishida (1901-72), who made around 90 films between 1926 and 1947,but the only other one which is relatively easy to find in decent quality with Englishsubtitles is Fallen Blossoms (1938).

BONUS TRIVIA: If theactor playing Eiko’s father looks familiar, that’s probably because it’s EitaroShindo, who went on to play the title role in Kenji Mizoguchi’s masterpiece Sansho Dayu (1954)

Some of the informationabove comes from a review on Amazon Japan by ‘Beautiful Summer.’

Thanks to A.K.

August 6, 2025

Woman Unveiled / 女であること / Onna de aru koto (‘Being a Woman’, 1958)

Yoshiko Kuga

Yoshiko Kuga

Masayuki Mori and Setsuko Hara

Masayuki Mori and Setsuko Hara

Sadatsugu (MasayukiMori), a lawyer, and his wife Ichiko (Setsuko Hara) are a childless couple whoare looking after the daughter of one of Sadatsugu’s clients, who is facing adeath sentence, though we never learn precisely what for. The daughter, namedTaeko (Kyoko Kagawa), appears to be in her late teens, and is sensitive, timidand rather gloomy, perhaps mostly due to her father’s situation.

Sadatsugu andIchiko then find themselves having to look after another young woman of asimilar age, Sakae (Yoshiko Kuga), who has run away from home and is thedaughter of Ichiko’s best friend. Unlike Taeko, Sakae turns out to be a spoilt,insensitive troublemaker with no filter and no control over her emotions. It’snot long before she’s annoying Taeko with her directness, flirting withSadatsugu and even coming home drunk and kissing Ichiko on the lips. Meanwhile,Ichiko has a chance meeting with old flame Goro (Tatsuya Mihashi), whom shehasn’t seen for 17 years. Then Sakae finds out and starts sticking her oar in…

This production by TokyoEiga (a subsidiary of Toho) was director Yuzo Kawashima’s first for them afterleaving Nikkatsu. It was based on an untranslated novel of the same name byYasunari Kawabata originally serialised in the Asahi Shinbun during 1956. Despite the fact that it’s notconsidered one of future Nobel laureate Kawabata’s most notable works,Kawashima – along with his collaborators Sumie Tanaka (female) and Toshiro Ide(male) – is said to have gone to a great deal of trouble over the screenplay.By all accounts a pretty faithful adaptation, nevertheless Kawashima apparentlyregarded the film as a failure, feeling that he had failed to make of it anymore than an illustrated version of the novel’s key scenes. It’s also likelythat some important aspects had to be implied in the film version due tocensorship – for example, that Sadatsugu and his wife haven’t slept togethermuch in their ten years of marriage, and that Ichiko’s interest in sex isrevived partly due to her kiss with Sakae and partly as a result of meetingGoro again. There’s also some suggestion that Sadatsugu sleeps with Sakae, butit’s not really made clear. However, what’s more frustrating is that we learnnothing of the crime for which Taeko’s father is facing a death sentence and,in fact, never even lay eyes on him – it’s simply a convenient device to giveher something to feel troubled about. It seems to me that the inclusion of sucha story element rather obliges the writers to expand a little (I would assumethat Kawabata went into more detail in his book).

The film opens with amontage sequence of Yoshiko Kuga shot from behind riding around on her bike andshouting out greetings to various passers-by. This is followed by Akihiro Miwa,the drag queen from Black Lizard(1968), dancing and singing the title song (i.e. ‘Being a Woman’) over theopening credits before two American military planes go roaring overhead, scaringKyoko Kagawa’s pet bird. It’s hard to know what to make of this opening – apart fromwhimsy on the part of Kawashima – as none of it seems to bear much relation towhat follows.

Though by no means abad film, Woman Unveiled alsofeatures a disappointingly corny, Hollywood-style score by Toshiro Mayuzumi andwraps things up in mostly conventional fashion, although the change undergone byKyoko Kagawa’s character is somewhat unexpected. The posters promoted SetsukoHara as the main star, but it’s Yoshiko Kuga who steals this one – theterm ‘charm offensive’ springs to mindhere, as she simultaneously manages to be both charming and offensive. Incidentally, the role is strikingly similar to theone she played in the previous year’s Banka(aka Northern Elegy), in which shealso caused trouble for a middle-aged and married professional played byMasayuki Mori. For all its flaws, WomanUnveiled remains a well-made and intelligent film arguably more in theNaruse mould than the Kawashima one (if such a thing existed) with a trio ofvery different but interesting and well-rounded female characters at its centre.

Thanks to A.K.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

August 2, 2025

Rats of the Town / 江戸の小鼠たち / Edo no koizumi tachi / (‘Little Rats of Edo’, 1957)

Masahiko Tsugawa

Masahiko Tsugawa

1832. Jirokichi(Masahiko Tsugawa) is an angry young man living in a tenement in Edo (nowTokyo) at a time when poverty is widespread and corruption is rife. Hisnamesake, the real-life thief Jirokichi (better-known as Nezumi Kozo, or ‘RatBoy’)* has just been executed. Like many young men, Jirokichi idolises him as asort of Robin Hood-figure who helped the poor and continually outsmarted TheMan. Unfortunately, his attempts toemulate his hero tend to cause trouble for his fellow tenement-dwellers, and hereceives no parental guidance as his mother is dead, while his father (AkitakeKono) is unemployed and gambles away what little money they have.

Izumi Ashikawa

Izumi AshikawaThe girl next door, Okin(Izumi Ashikawa), works at a teahouse and, to Jirokichi’s annoyance, is courtedby a young samurai, Kakusaburo (Hiroyuki Nagato). Jirokichi picks a fight withhim and wins, after which the two become friends. Some local yakuza whowitnessed the fight decide to employ Jirokichi. Despite the fact that he hadpreviously fought against the yakuza when he saw them ripping off the poor, he’snow happy to work for The Man as the other tenement-dwellers have come to seehim as a troublemaker and turned against him. Only Okin still believes in himas she remembers all the times he protected her when she was a young girl…

Hiroyuki Nagato

Hiroyuki NagatoThis Nikkatsuproduction was based on a then newly-published novel by Genzo Murakami, a specialistin samurai tales. The two young male stars, Masahiko Tsugawa (17) and HiroyukiNagato (23), were not only brothers, but were also both associated withso-called ‘sun tribe’ pictures – Tsugawa with Crazed Fruit and Nagato with Seasonin the Sun (both 1956). Although this film is by no means a ‘sun tribe’ jidaigeki (period drama), it’s obviousthat it was made to appeal to the youth market.

Directed by veteran TaizoFuyushima, who made Joshu karasu (seemy review for more on him), like that film, this one is very well-made andentertaining with quite a lot of humour if not a great deal of depth, and alsofeatures some excellent cinematography, in this case by Shohei Imamurafavourite Shinsaku Himeda. Transposed to another era, Jirokichi is akin to the typical nihilistic young rebel of post-war Japan who felt let down by the older generation (represented by here by his worse than useless father), but the light, conventional tone of the ending negates any impact the film might have had.

Watched with dodgy subtitles.

*This historical figurebecame the hero of various kabuki plays, novels and motion pictures in Japan;of the latter, Daisuke Ito’s Jirokichithe Rat (1931) is the most notable.