Bee Ridgway's Blog

October 16, 2013

In the Kingdom of the Blind

I’ve been asked many times about how old I was when I knew I was a writer. I don’t think I accepted that I was a writer of fiction until I was 39, the year I started The River of No Return. But I have always been fascinated by fiction, by storytelling, by the fine line between truth and fiction. Many of my earliest memories are, in one way or another, about the power of fiction. This one that I’m about to tell you is a sad story. Fundamentally it’s about betrayal – with me in the part of the bad guy.

I’ve been asked many times about how old I was when I knew I was a writer. I don’t think I accepted that I was a writer of fiction until I was 39, the year I started The River of No Return. But I have always been fascinated by fiction, by storytelling, by the fine line between truth and fiction. Many of my earliest memories are, in one way or another, about the power of fiction. This one that I’m about to tell you is a sad story. Fundamentally it’s about betrayal – with me in the part of the bad guy.I first learned to make fiction when I was in the hospital. I was four.

That year, I lost the sight in my right eye due to a rare, hard-to-diagnose condition. There was nothing to be done, but once they had managed to diagnose it, the doctors at Massachusetts Eye and Ear wanted me to come to the hospital in Boston for a week, so that they could show my eye to students and take photographs of my retina for textbooks.

I could still see perfectly well out of my left eye, but my brain had not yet learned to ignore the message that my blind eye was sending: Darkness – Darkness! Because my brain was still melding the information received from both my eyes into one picture, my vision was distorted and washed across with black.

I was put into the blind children's ward at the hospital. My sight was temporarily darkened, but some of the children were terribly sensitive to brightness, so the walls were painted gray, and the lights were very dim. There were three big, wooden cribs in my dark room. The cribs offended me: I wasn’t a baby. To add insult in injury, the cribs had plastic bubbles that fixed to them, to keep their inmates from climbing out. I was further offended: I knew better than to do that.

Nevertheless, there I was, confined. Mine was the crib by the door. The middle crib held a little girl, only two years old, who had lost her sight to a quick-moving degenerative disease. The child in the crib by the window (always kept shuttered) was a boy my age. He was newly blind, and he wanted, incessantly, to play soldiers. He would stick his arm out through the slats and shoot at me with his index finger, through and across the little girl’s crib. Normally, I was not allowed to play war games. But my mother, torn between her pacifism and her sympathy for the boy, decided that I should play along with him. So I was allowed to shoot back.

Nevertheless, there I was, confined. Mine was the crib by the door. The middle crib held a little girl, only two years old, who had lost her sight to a quick-moving degenerative disease. The child in the crib by the window (always kept shuttered) was a boy my age. He was newly blind, and he wanted, incessantly, to play soldiers. He would stick his arm out through the slats and shoot at me with his index finger, through and across the little girl’s crib. Normally, I was not allowed to play war games. But my mother, torn between her pacifism and her sympathy for the boy, decided that I should play along with him. So I was allowed to shoot back.It was fun, reaching my arm out with such willful purpose, my finger a pistol. I yelled: “Bang! Bang!” The forbidden words felt good on my tongue. I loved what the boy was teaching me. I relished the feelings the new game cooked up in my heart: danger, power, exhilaration.

But there was a technical problem. It was clear to me that he was failing to hit me, or even to shoot anywhere near me, while I, on the other hand, nailed him every time, right in the heart. Nevertheless, he refused to die. “I hit you,” I yelled. “Did not! I hit you,” he yelled back. “Did not,” I yelled. This went on and on, until finally I felt it necessary to explain to him that I could tell he had been hit, and that I was unscathed. After all, I told him, I could see, and he was blind.

My mother was horrified. “You pretend,” she whispered. “He will never see again. You pretend he hit you.”

With my mother’s words, my entire universe shifted around me. I understood the meaning of what I had just said to the boy: “I can see and you are blind.” I felt what I had never felt before: the extreme precariousness of existence. At the same time I felt a sagging sort of relief as I realized my luck. I was in the blind ward, surrounded by blind children, but I could see. I was going to go back to light, to colors, while the newly blind boy didn’t even know that the room we were in was dark and gray. He didn’t even know that he couldn’t convincingly hit anybody with a gun-finger. I was four years old. In retrospect I am appalled by my own bloodthirsty self-absorption. I don’t think I felt pity, or empathy, or anything at all other than the adrenaline-driven wonder at being, myself, safe in my ability to see.

With my mother’s words, my entire universe shifted around me. I understood the meaning of what I had just said to the boy: “I can see and you are blind.” I felt what I had never felt before: the extreme precariousness of existence. At the same time I felt a sagging sort of relief as I realized my luck. I was in the blind ward, surrounded by blind children, but I could see. I was going to go back to light, to colors, while the newly blind boy didn’t even know that the room we were in was dark and gray. He didn’t even know that he couldn’t convincingly hit anybody with a gun-finger. I was four years old. In retrospect I am appalled by my own bloodthirsty self-absorption. I don’t think I felt pity, or empathy, or anything at all other than the adrenaline-driven wonder at being, myself, safe in my ability to see. The game was no longer a game. I interpreted my mother’s words – "you pretend" – to mean that because I could see, I must lie. I didn’t have to do much to execute this duty. I didn’t even have to stick my arm out of my crib. I could just sit on the thin, plastic-covered mattress and say “Bang,” then “Oh, ow, I’m dead.”

It was a horrible, hollow – even an evil – sort of victory. I was no longer playing, I was pretending to play. I thought I was the winner, before the game even began.

I watched him now with the detached interest of a scientist (or perhaps, of a writer). I felt his excitement in the game slap against the plastic bubble that kept me in my cage. He leaned his skinny chest hard against the bars of his, his gun-arm reaching out toward me as far as it could strain, his eyes open wide over his smile, his finger crooking as he shot. I sat at my ease and watched him and I said the things he wanted to hear. That I was exchanging fire with him, that he could touch me, that he could alter my being.

Two children playing at war can transform a darkened hospital room into a battlefield with nothing more than their eager fingers and their shrill voices. Children imagining together are not making fiction, in the way that adults make fiction. When I claimed that the blind boy’s bullets weren’t hitting me, I broke the toy of childhood make-believe. In order to patch it back together again for his continued pleasure, I had to become a maker of fiction, a fabulist, a little man behind the curtain. But what I had yet to learn is that working alone to make fiction is hard. Creating a world that can seduce a reader requires intense commitment. A good writer can’t just sit cross-legged and say “bang bang” in a bored voice.

Two children playing at war can transform a darkened hospital room into a battlefield with nothing more than their eager fingers and their shrill voices. Children imagining together are not making fiction, in the way that adults make fiction. When I claimed that the blind boy’s bullets weren’t hitting me, I broke the toy of childhood make-believe. In order to patch it back together again for his continued pleasure, I had to become a maker of fiction, a fabulist, a little man behind the curtain. But what I had yet to learn is that working alone to make fiction is hard. Creating a world that can seduce a reader requires intense commitment. A good writer can’t just sit cross-legged and say “bang bang” in a bored voice.I think I remember the moment the game ended forever, but I’m not sure what it is that I remember. I think I remember watching the transition, as he realized that he was playing alone, that I was only pretending to pretend. I think I remember watching his face change, seeing the expression of bleak understanding come into his eyes – his blind eyes. His gun-hand withdrew. I think I remember seeing that. But that is overly sentimental, so like a movie. With our greedy eyes we watch the blind child realize his terrible loss. Surely I made that part up?

The other thing I might remember is a sound, not a sight. My mother sat beside my crib, reading. She sat there all week, day in and day out. She even slept in her chair, never once leaving me alone. I think that I might remember sitting in my crib, facing the room and the boy, and hearing, behind me, the sound of my mother slipping a finger under a page as she read. Then a pause as she came to the end of the page, then the crisp sound of paper lifting up and turning over. But that seems overly symbolic, so like a novel. And so, with the loss of innocence, one chapter of life ends and another begins. Surely I have superimposed the memory of my mother turning a page onto my memory of the end of the game?

The other thing I might remember is a sound, not a sight. My mother sat beside my crib, reading. She sat there all week, day in and day out. She even slept in her chair, never once leaving me alone. I think that I might remember sitting in my crib, facing the room and the boy, and hearing, behind me, the sound of my mother slipping a finger under a page as she read. Then a pause as she came to the end of the page, then the crisp sound of paper lifting up and turning over. But that seems overly symbolic, so like a novel. And so, with the loss of innocence, one chapter of life ends and another begins. Surely I have superimposed the memory of my mother turning a page onto my memory of the end of the game? I have dedicated myself to fiction, as an English teacher and a novelist and, in my leisure time, as an escape artist. So perhaps, as I remember back to my time in the blind ward, fiction has overwhelmed me. Pretending to pretend to pretend . . . even now, my attempt to toss aloft some sort of “truth” about the making of fiction has succumbed to gravity. “Truth” has plunged back to my hand, untrue. My only memories of the blind boy serve my own self-fashioning. I don’t remember anything else at all about him, not even his name.

I have dedicated myself to fiction, as an English teacher and a novelist and, in my leisure time, as an escape artist. So perhaps, as I remember back to my time in the blind ward, fiction has overwhelmed me. Pretending to pretend to pretend . . . even now, my attempt to toss aloft some sort of “truth” about the making of fiction has succumbed to gravity. “Truth” has plunged back to my hand, untrue. My only memories of the blind boy serve my own self-fashioning. I don’t remember anything else at all about him, not even his name.

Published on October 16, 2013 10:42

August 26, 2013

Peter Pan at Bryn Mawr College

Next week I will walk back into the classroom, and I will transform from Bee Ridgway, novelist and author of that time travel adventure saga, The River of No Return, into Bethany Schneider, professor of 18thand 19th century American literature.

I’m looking forward to teaching – but I’m also nervous. This is the first time that the “new me” will have to behave as if I’m still the “old me.” Is “old me” the same, or has she changed?

This morning, as I worked on my syllabi, I found myself thinking about a speech I gave at Bryn Mawr several years ago, in which I compare the life of a college professor to the life of Peter Pan living in Neverland. I dug the old file up and re-read it. I realized that I must have partly written it for myself, for this very moment of return. I’m going to share the speech here.

A caveat: this speech is a bit smarmy! It was given to high school seniors who had been admitted to Bryn Mawr, but who had not yet decided whether to come. My job was to convince them that Bryn Mawr is the best. So it’s partly a sales pitch, I don’t deny it. But . . . it’s a sales pitch in which I believe. I’ve taught at Bryn Mawr since 2001, and I love it.

PETER PAN AT BRYN MAWR COLLEGE

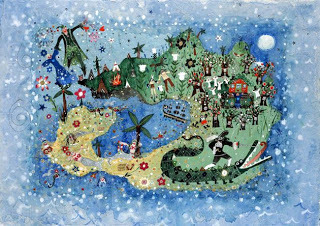

Mikhail Baryshnikov, Gisele Bündchen and Tina FeyI don’t know if you remember the end of Peter Pan. The three Darling children return from Neverland along with all of the Lost Boys. Only Peter refuses to come inside and grow up like the rest of them. Wendy and her mother try to convince him, and he says, passionately, “I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things! I don’t want to be a man!” He goes back to Neverland and lives with Tinkerbell. Every once in a while he comes back and looks longingly through the window at Wendy and the formerly Lost, now Found Boys. He watches them grow up, while he remains a kid in scrappy green rags. In the beginning of the play he is the one they all look up to, the one with the ideas, the one to take them to Neverland and show them things they couldn’t imagine. By the end they are mustachioed pillars of society and they have forgotten that they ever knew Peter Pan, that they could ever fly.

Mikhail Baryshnikov, Gisele Bündchen and Tina FeyI don’t know if you remember the end of Peter Pan. The three Darling children return from Neverland along with all of the Lost Boys. Only Peter refuses to come inside and grow up like the rest of them. Wendy and her mother try to convince him, and he says, passionately, “I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things! I don’t want to be a man!” He goes back to Neverland and lives with Tinkerbell. Every once in a while he comes back and looks longingly through the window at Wendy and the formerly Lost, now Found Boys. He watches them grow up, while he remains a kid in scrappy green rags. In the beginning of the play he is the one they all look up to, the one with the ideas, the one to take them to Neverland and show them things they couldn’t imagine. By the end they are mustachioed pillars of society and they have forgotten that they ever knew Peter Pan, that they could ever fly. Remembering Peter Pan– a fantastical play and then a book and then several films for children -- may seem like a strange way to introduce you to Bryn Mawr College, which is, as I’m sure you are aware, a scholarly liberal arts college. The sentences, “I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things! I don’t want to be a man!” seem pretty patently inappropriate. At Bryn Mawr you will be in school and you will most certainly learn solemn things. And as for not wanting to be a man, well. At Bryn Mawr we are in the business of helping young women become fabulously bad-assed in a world that is still stacked against them.

Remembering Peter Pan– a fantastical play and then a book and then several films for children -- may seem like a strange way to introduce you to Bryn Mawr College, which is, as I’m sure you are aware, a scholarly liberal arts college. The sentences, “I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things! I don’t want to be a man!” seem pretty patently inappropriate. At Bryn Mawr you will be in school and you will most certainly learn solemn things. And as for not wanting to be a man, well. At Bryn Mawr we are in the business of helping young women become fabulously bad-assed in a world that is still stacked against them.

So. I begin by remembering the end of Peter Pan not because I think you are like that boy in green, but because, after ten years of teaching at Bryn Mawr College, I have come to realize that I am like him. Several generations of Bryn Mawr women have now passed through my classrooms. All of them have been, in their own way, full of spit and vinegar, as my grandmother would say. I always feel as if the group of women I’m teaching at the moment will be here forever. I feel like together, they and we – these particular students, the professors and staff – are Bryn Mawr, forever. But of course a Bryn Mawr woman takes everything at a gallop. She storms through the place and you can tell when she’s ready to go, because of the transformation not only in her knowledge, but also in her self-possession, her humor, her courage, the attunement of her mind. Off she goes to conquer the world.

So. I begin by remembering the end of Peter Pan not because I think you are like that boy in green, but because, after ten years of teaching at Bryn Mawr College, I have come to realize that I am like him. Several generations of Bryn Mawr women have now passed through my classrooms. All of them have been, in their own way, full of spit and vinegar, as my grandmother would say. I always feel as if the group of women I’m teaching at the moment will be here forever. I feel like together, they and we – these particular students, the professors and staff – are Bryn Mawr, forever. But of course a Bryn Mawr woman takes everything at a gallop. She storms through the place and you can tell when she’s ready to go, because of the transformation not only in her knowledge, but also in her self-possession, her humor, her courage, the attunement of her mind. Off she goes to conquer the world.  So you see – as a professor to this particularly amazing breed, this Bryn Mawr woman, I feel a bit like Peter Pan, who lives forever on an enchanted island where others tarry . . . but eventually leave, eventually grow up. If I’m Peter, Bryn Mawr is, in certain ways, Neverland. I don’t mean that it is childish or silly. Far from it. Peter Pan lures boys away from humdrum family nurseries where they are locked into rather dreary childish behaviors, to a thrilling island fraught with danger and excitement, where they live on the razor’s edge between life and death, and find their pleasure there. Like Peter Pan, I feel that I can offer you something that beautiful and also dangerous, something marvelously different from the confinements of youth.

So you see – as a professor to this particularly amazing breed, this Bryn Mawr woman, I feel a bit like Peter Pan, who lives forever on an enchanted island where others tarry . . . but eventually leave, eventually grow up. If I’m Peter, Bryn Mawr is, in certain ways, Neverland. I don’t mean that it is childish or silly. Far from it. Peter Pan lures boys away from humdrum family nurseries where they are locked into rather dreary childish behaviors, to a thrilling island fraught with danger and excitement, where they live on the razor’s edge between life and death, and find their pleasure there. Like Peter Pan, I feel that I can offer you something that beautiful and also dangerous, something marvelously different from the confinements of youth.  Bryn Mawr reaches out to the world, its mission is the education of women for the global present. You won’t be isolated here, or cut off. But I want you to also understand that Bryn Mawr is, like Neverland, an island. It is a collective fantasy. I mean that positively -- I think it's a good thing in a college. The term “ivory tower” is used disparagingly, and the isolation of academia is often critiqued. We work hard at Bryn Mawr to make sure our students are citizens of a contemporary and dynamic world. But an important part of a liberal arts education is the small community of scholars working together, "we happy few." You’ve been on the tour, and you’ve seen the beautiful cloister that is at the heart of Bryn Mawr, the secluded space that recalls the history of higher education in Europe. Bryn Mawr reaches outward, yes, it prepares you for a life outside and away from it . . . but that inward-turning part of the college is precious. It is the Neverland at the heart of this place.

Bryn Mawr reaches out to the world, its mission is the education of women for the global present. You won’t be isolated here, or cut off. But I want you to also understand that Bryn Mawr is, like Neverland, an island. It is a collective fantasy. I mean that positively -- I think it's a good thing in a college. The term “ivory tower” is used disparagingly, and the isolation of academia is often critiqued. We work hard at Bryn Mawr to make sure our students are citizens of a contemporary and dynamic world. But an important part of a liberal arts education is the small community of scholars working together, "we happy few." You’ve been on the tour, and you’ve seen the beautiful cloister that is at the heart of Bryn Mawr, the secluded space that recalls the history of higher education in Europe. Bryn Mawr reaches outward, yes, it prepares you for a life outside and away from it . . . but that inward-turning part of the college is precious. It is the Neverland at the heart of this place.  Let me explain by turning to the past. M. Carey Thomas, the school’s second president, called Bryn Mawr her “fairy college,” because back then when women’s choices were so limited, it felt as if she and her colleagues were building a fragile, magical oasis outside of cold reality. That’s partly why she insisted on the Collegiate Gothic style for the buildings, rather than the plain Quaker style of Haverford. She knew that Bryn Mawr was desperately needed, and she knew it needed to be almost mystical in quality – a previously unimaginable place where female students could practice being free and passionate intellectuals. She knew they needed that “fairy college,” that place of secluded preparation, because when they left, they would have to fight for every scrap of recognition they could get outside the college’s walls. Women have made great strides since the late 19th century, but the journey isn’t nearly over. And Bryn Mawr is still here. It is still enchanting in the best sense of the word. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. Enchantment should be scary. It should be dangerous. It should change you into something you couldn’t have previously imagined, it should whirl you away from the life you know. It should, in other words, make you into a creature who can fly. And unlike the poor Lost Boys who trade fantasy for respectability, the flying lessons you receive at Bryn Mawr will never forsake you.

Let me explain by turning to the past. M. Carey Thomas, the school’s second president, called Bryn Mawr her “fairy college,” because back then when women’s choices were so limited, it felt as if she and her colleagues were building a fragile, magical oasis outside of cold reality. That’s partly why she insisted on the Collegiate Gothic style for the buildings, rather than the plain Quaker style of Haverford. She knew that Bryn Mawr was desperately needed, and she knew it needed to be almost mystical in quality – a previously unimaginable place where female students could practice being free and passionate intellectuals. She knew they needed that “fairy college,” that place of secluded preparation, because when they left, they would have to fight for every scrap of recognition they could get outside the college’s walls. Women have made great strides since the late 19th century, but the journey isn’t nearly over. And Bryn Mawr is still here. It is still enchanting in the best sense of the word. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. Enchantment should be scary. It should be dangerous. It should change you into something you couldn’t have previously imagined, it should whirl you away from the life you know. It should, in other words, make you into a creature who can fly. And unlike the poor Lost Boys who trade fantasy for respectability, the flying lessons you receive at Bryn Mawr will never forsake you. Um yes this is from a Bryn Mawr yearbookOne thing I love most about teaching is watching my students find their wings. I could tell dozens of stories about how my students have woken up to their passions and fascinations while at Bryn Mawr. But I’ll tell you just one, tonight. It’s simple, but it encapsulates the transformation that the "fairy college" can produce. I’ll call this student Moira. She turned up at Bryn Mawr, shy as a chipmunk. She was literally fresh from the farm in Iowa, and she sat quietly at the freshman seminar table day after day, hiding behind her hair. She wrote the most incredible papers, but if I called on her, she looked at me reproachfully from under her bangs, and said nothing.

Um yes this is from a Bryn Mawr yearbookOne thing I love most about teaching is watching my students find their wings. I could tell dozens of stories about how my students have woken up to their passions and fascinations while at Bryn Mawr. But I’ll tell you just one, tonight. It’s simple, but it encapsulates the transformation that the "fairy college" can produce. I’ll call this student Moira. She turned up at Bryn Mawr, shy as a chipmunk. She was literally fresh from the farm in Iowa, and she sat quietly at the freshman seminar table day after day, hiding behind her hair. She wrote the most incredible papers, but if I called on her, she looked at me reproachfully from under her bangs, and said nothing. Then one day a stranger walked into the room and sat in Moira’s usual spot. She had a sharp new haircut and she was dressed in a black vintage dress. She raised her hand right away and proceeded to say fantastic things. After class I asked Moira what had happened. She smiled easily at me, with a sort of breezy confidence. “Well, Professor,” she said, “Over the weekend I realized that I was here, at Bryn Mawr, and I just . . . changed!” In her senior year, Moira – the formerly shy chipmunk -- directed the funniest, most outrageous, most un-shy production of The Importance of Being Earnest that I have ever seen.

Unlike Peter Pan, I stay in touch with my Lost Boys, who are neither lost nor boys. My old students are out there in the world, running their own businesses, teaching, healing, researching, traveling, they are in politics and publishing and law, they have families, they are activists and artists and chefs and rabbis, nurses and doctors and actors – and because I teach English and many of my students love to write, many of them go away and become writers – food writers, children’s book writers, novelists, journalists, playwrights . . . they have scattered all over the world, they inhabit every walk of life, every kind of life. I hope that someday some of you will be among them!

So a very heartfelt welcome to Bryn Mawr College – I hope that you enjoy your time here. Please feel free to email me if you have any questions . . .

Published on August 26, 2013 14:37

August 10, 2013

Skunk Coat

This photo was taken sometime in the mid 1920s at the train station in Sussex, New Brunswick. The two people are Millie Winger and Henry Schneider. Henry is a young dairy farmer. Millie is the eldest of five daughters; her father is a minister. She is a piano player, and there has been some talk about her playing professionally. But she’s marrying Henry and she’s going to be a farmer’s wife.

Actually, I don’t know if this photo was taken before or after their marriage. All I really know is that Millie, my grandmother, is wearing a skunk-skin fur coat. That’s what that is. And Henry, my grandfather, is rocking a pair of faded overalls under a worn-looking wool coat. It’s the middle of a workday for him, but it’s the start or the end of some journey for her. They are pausing in the cold, bright, Canadian light to have their picture made in front of what looks like a new, or at least a nice, car.

It’s a portrait of their love. They are quite obviously delighted with each other. And the picture is also a portrait of their idea of their future. Both Millie and Henry were born in Europe, in the 19th century. But now it’s 1920-something, they’re in the New World. Henry has a car, they are at the train station, and Millie . . . in her skunk coat, her hair bobbed, those glasses, that cloche hat . . . she’s going places. She is a modern girl.

He’s not such a modern boy. He’s a farmer, and he’s dressed for the same labor his ancestors have done for hundreds of years. He’s comfortable in that role, at home. You can see his comfort in his body. Lounging there, hand in his pocket. But look closely at the shadow under his cap. Peer into that dark, and you’ll see . . . he’s totally besotted with her. With this future-oriented creature. He likes her just the way she is. She delights him.

He’s quite a lot better looking than she is. To be honest, she’s a frump, in spite of the skunk coat and the cloche. She’s fundamentally dumpy. He likes that about her, too. Likes that she makes a whole lot out of a little, likes that she overdoes it. Look again at the look on his face. He enjoys her. Not just in this moment, but in her essence. He likes to sit back and watch her go.

She’s laughing, clutching that purse . . . a little stiff, a lot joyous. She’s a plump dynamo. It’s funny. His emotions are perfectly legible in spite of the shadow over his face. But we can’t really tell what she’s thinking, what she likes or doesn’t like. That’s the condition of those who push the future forward, though. They don’t know what they want, except that whatever it is, they want more. It’s why they’re fun when they’re young. It’s also why they often stop being fun when they get older.

She’s laughing, clutching that purse . . . a little stiff, a lot joyous. She’s a plump dynamo. It’s funny. His emotions are perfectly legible in spite of the shadow over his face. But we can’t really tell what she’s thinking, what she likes or doesn’t like. That’s the condition of those who push the future forward, though. They don’t know what they want, except that whatever it is, they want more. It’s why they’re fun when they’re young. It’s also why they often stop being fun when they get older.But here she’s young. Check out this picture of her, spinning along in a contraption of some kind, with her stockings showing. It’s the decade of her youth, and she’s enjoying it.

Of course we know what’s coming. Depression. War. And I know the details of how those vast, global convulsions touched Millie and Henry, first on the farm in Wisconsin and then on the farm in California, where they moved in 1946. I know that her ambition for more changed its shape when she had children. I know how that searing ambition radically shaped the course of my father’s life.

Millie has been gone for forty years, Henry for a few years longer. I never met him, and I have no memory of her, although apparently we got along famously and she used to get down on her hands and knees and play “cow” with me in the flooded front yard of the California farm. Here we are. The skunk coat is long gone, but don't worry. That’s a big old wig she’s wearing. And silver cat's eye glasses.

Millie has been gone for forty years, Henry for a few years longer. I never met him, and I have no memory of her, although apparently we got along famously and she used to get down on her hands and knees and play “cow” with me in the flooded front yard of the California farm. Here we are. The skunk coat is long gone, but don't worry. That’s a big old wig she’s wearing. And silver cat's eye glasses.About eight years ago I was teaching some novel – I don’t remember which one – and there was something in it about how the sins of our ancestors descend to curse the present generation (sounds like tons of novels, right?). Anyway, we were talking about the burdens of the past, and a student raised her hand. I remember this as clearly as if it were yesterday. I called on her, and she said “I really can’t relate, because none of my ancestors ever did anything bad.” I think my mouth hung open. I know I didn’t say anything right away, because another student said, “What do you mean, like, none of your ancestors, all the way back to Lucy?” And this student said, with perfect confidence, “That’s right.”

That’s a lot of people to have never done anything bad.

I have a few really unsavory ancestors, ancestors whose sins stain the pages of history. And quite a lot of ancestors whose sins were quieter. Hateful people. Bitter people. So does everyone, of course, though I suppose it’s possible that my student really was the product of hundreds of generations of pure and virtuous behavior. Who am I to say? I know I would find it stressful to be the beloved child of hundreds of generations of beloved children. How scary! What if you are the one who falls!

Millie and Henry made mistakes, of course. Big ones. But I think they might be my best shot at what my student might have deemed “good” ancestors. Nice, hardworking people. The salt of the earth.

That’s why I love this photo. That crazy skunk coat on Millie. That shadowy amusement on Henry’s face. The sexy way his body bends toward her. That’s vanity and lust right there. Beautiful, joyful vanity and lust. At least at this moment, Henry and Millie aren’t participating in a trans-historical project of virtuous reproduction. They are enjoying themselves, enjoying their moment. Having fun.

Phew.

Published on August 10, 2013 17:09

July 30, 2013

The Awful Truth: Cary Grant and Sex

My favorite movie of all time is His Girl Friday. There are a billion things to love about it, some of them very deep, very profound, all about a moment in American cinema when . . . but never mind. Let’s talk about Cary Grant. He’s completely and entirely exquisite in His Girl Friday. He’s so funny you could burst from the laughter. So poised that it’s like that late-night diner trick where you balance a saltshaker on its edge. So insanely, over-the-top, extraordinarily handsome that your teeth ache and you want to weep. But your tears are as fruitless as Echo’s, when she is weeping for Narcissus.

My favorite movie of all time is His Girl Friday. There are a billion things to love about it, some of them very deep, very profound, all about a moment in American cinema when . . . but never mind. Let’s talk about Cary Grant. He’s completely and entirely exquisite in His Girl Friday. He’s so funny you could burst from the laughter. So poised that it’s like that late-night diner trick where you balance a saltshaker on its edge. So insanely, over-the-top, extraordinarily handsome that your teeth ache and you want to weep. But your tears are as fruitless as Echo’s, when she is weeping for Narcissus.

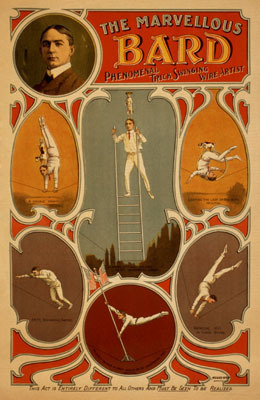

Not that Cary Grant comes off as a narcissist in his movies, because he doesn’t. Part of his perfection is that ever-so-slight hint of self-deprecation. After all, you know, he had a terrible – I mean a terrible –childhood. Then, at the age of fourteen, he was kicked out of school. He ran away and basically joined the circus. He spent his teens with a vaudeville act as an acrobat. Can you imagine? The youth who became that elegant man, dressed in whatever shabby acrobat outfit he had to wear, all big brown eyes, flying through the air with the greatest of ease . . . before he shed his ugly name and pretty accent. He must have been the prince of the Ephebes. Can’t you just hear the cougars roaring?

Not that Cary Grant comes off as a narcissist in his movies, because he doesn’t. Part of his perfection is that ever-so-slight hint of self-deprecation. After all, you know, he had a terrible – I mean a terrible –childhood. Then, at the age of fourteen, he was kicked out of school. He ran away and basically joined the circus. He spent his teens with a vaudeville act as an acrobat. Can you imagine? The youth who became that elegant man, dressed in whatever shabby acrobat outfit he had to wear, all big brown eyes, flying through the air with the greatest of ease . . . before he shed his ugly name and pretty accent. He must have been the prince of the Ephebes. Can’t you just hear the cougars roaring? Like all circus runaways, he made himself up out of broken pieces, and when he put himself together, he put himself together just a little bit wrong. A little bit (perfectly) askew. That made-up (perfect) accent (remember Tony Curtis lampooning Grant: “Nobody talks like that!”). That unbelievable handsomeness, a beauty that could crack heaven’s dome, put to the task of (perfect) slapstick hilarity. It’s irresistible. It’s immortal.

Like all circus runaways, he made himself up out of broken pieces, and when he put himself together, he put himself together just a little bit wrong. A little bit (perfectly) askew. That made-up (perfect) accent (remember Tony Curtis lampooning Grant: “Nobody talks like that!”). That unbelievable handsomeness, a beauty that could crack heaven’s dome, put to the task of (perfect) slapstick hilarity. It’s irresistible. It’s immortal. Here’s my question, though. It’s irresistible, it’s immortal . . . but is it sexy?

On the one hand, that’s a stupid question. Let’s say that Cary Grant knocks on your door and says “Hell-ow, how about it, you and me?” Would you say, “no thank you?” Obviously not. You would say, “Come right in, Mr. Grant, and make yourself comfortable while I kick my true love out the back door with instructions to not come back for an hour and half.” And your true love, if they have a soul, would wish you luck and check your breath and straighten your collar and be proud as punch of you. Because come on: Cary Grant.

But still. The question lingers. Cary Grant. Sexy . . . or is part of the secret of his manifold, fractal perfections the fact that . . . not so much?

Let’s pull back and look at the big picture. Cary Grant made movies between the years of 1932 and 1966. In those first two years of his career you could put a whole lot of sex in your movies, and actors and directors ladled it on. Grant appears in ’32 and ’33 as the hunky young man whose dark good looks attract the attention of such smokingly sexy women as Marlene Dietrich and Mae West. Those films – Blonde Venus, She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel are amazing and they are hot as hell. And Cary Grant’s in them (third billing). But is it Grant who stokes the flames? Nope. These movies are sexy because of Dietrich and West. Grant is a pretty face. You almost don’t recognize him, he’s so placidly gorgeous.

Let’s pull back and look at the big picture. Cary Grant made movies between the years of 1932 and 1966. In those first two years of his career you could put a whole lot of sex in your movies, and actors and directors ladled it on. Grant appears in ’32 and ’33 as the hunky young man whose dark good looks attract the attention of such smokingly sexy women as Marlene Dietrich and Mae West. Those films – Blonde Venus, She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel are amazing and they are hot as hell. And Cary Grant’s in them (third billing). But is it Grant who stokes the flames? Nope. These movies are sexy because of Dietrich and West. Grant is a pretty face. You almost don’t recognize him, he’s so placidly gorgeous. Then, in 1934, a thing called “The Code” – short for “The Motion Picture Production Code” – changed everything. It radically curtailed how sex could be represented in the movies. Overnight, movies changed. They got lighter, they got frothier, more flirty, less smoldering. It was in the early days of the Code-era that Cary Grant went from being handsome decoration to being the sparkling, antic faun we know and love. His early hits, where we suddenly see that he’s a screaming comic genius – His Girl Friday, Topper, The Awful Truth – were all made immediately post-Code.

So yeah. Cary Grant the living, breathing man was married five times to women, and may or may not have also been lovers with men, most famously his best friend, the super gorgeous Randolph Scott. Be that as it may, Grant, in his private life, was a sexual person. The persona of Cary Grant, on the other hand, the genius, the enthralling perfection of Cary Grant the movie star . . . that Cary Grant came to flower in precisely the years of the film industry’s greatest prudery.

So yeah. Cary Grant the living, breathing man was married five times to women, and may or may not have also been lovers with men, most famously his best friend, the super gorgeous Randolph Scott. Be that as it may, Grant, in his private life, was a sexual person. The persona of Cary Grant, on the other hand, the genius, the enthralling perfection of Cary Grant the movie star . . . that Cary Grant came to flower in precisely the years of the film industry’s greatest prudery. He left films long before he died, claiming that he wanted to spend time with his daughter. He was also getting along in years. There is something a bit disturbing about seeing Grant opposite Audrey Hepburn in Charade, when he’s 59 and she’s 34. But whatever the reason, Grant left filmmaking as the Code was crumbling, just when sex was on its way back in.

This is interesting to me for lots of reasons, but mostly because I am an inveterate reader of “vintage” romance novels, in which there isn’t any sex. And I write genre mash-up novels that draw some inspiration from the Code-era screwball comedies I love, and from that old-timey romance reading I enjoy. But my books have sex in them and my heroes and heroines need to be the kind of people who might get down to it at any point. It’s funny how difficult it is to blend froth and steam. In fiction as in cooking, they don’t really get along.

All of which is to say -- can we imagine Cary Grant sans his high-waisted, pleated culottes? Do we want to?

Last night the answer to that question slapped me in the face like a cold, dead salmon. And I’m still in shock. I watched a Grant movie I’d never seen before. It’s not one of his best known, but it isn’t exactly obscure. Maybe you’ve seen it. It’s called I Was a Male War Bride.

If you haven’t seen it, you should: I Was a Male War Bride is uproarious. Sort of like Some Like it Hot (an amazing film) if Some Like it Hot actually had Cary Grant in it, instead of Tony Curtis pretending to be Cary Grant. It’s got this great leading lady, Ann Sheridan, who is totally bad-assed and she and Cary Grant get into all sorts of ridiculous scrapes, careening across Europe in the months after the end of the Second World War. They’re just married and they can’t find anywhere to spend the night alone. It’s an amazing portrait of women in the war, too – just at that moment when women were still Rosie the Riveter and not yet June Cleaver. Fantastic stuff. What could be better?

If you haven’t seen it, you should: I Was a Male War Bride is uproarious. Sort of like Some Like it Hot (an amazing film) if Some Like it Hot actually had Cary Grant in it, instead of Tony Curtis pretending to be Cary Grant. It’s got this great leading lady, Ann Sheridan, who is totally bad-assed and she and Cary Grant get into all sorts of ridiculous scrapes, careening across Europe in the months after the end of the Second World War. They’re just married and they can’t find anywhere to spend the night alone. It’s an amazing portrait of women in the war, too – just at that moment when women were still Rosie the Riveter and not yet June Cleaver. Fantastic stuff. What could be better? Except you will have to steel yourself for one particular scene. In spite of the Code, this film manages to slip in a bedroom encounter that is obviously a stand-in for a sex scene. And I’m warning you. It isn’t pretty. In fact, it creates a jagged rip in the magical silver screen, revealing the hairy-knuckled possibility that Cary Grant was . . .

It’s hard to type it . . .

Cary Grant was potentially – just potentially, mind you -- bad in bed.

Now I watched this film as a streaming video and no one has decided to post it on the internet, so I cannot share the trauma with you here. I’m grateful. I am simply warning you that, when you get around to watching I Was a Male War Bride, you will be subjected to the sight of Cary Grant straddling a woman in bed and giving her a “massage.”

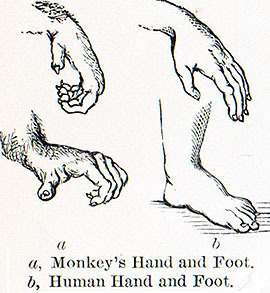

I put “massage” in quotes because what we actually see him doing is awkwardly sitting on her as if she were a tree stump, and grasping fistfuls of her flesh as if she were made of play dough. He squeezes, quick and fierce, then moves on to another fistful. He isn’t even symmetrical in his movements, but just sort of clutches at her randomly. You can see that she’s in agony – her body stiff even as she sighs and says “that feels so good.” Meanwhile he is staring down at his hands as if in shock at his own ineptitude. For a brief moment before the scene mercifully ends and the film leaves the horror genre behind and gets back to being hilarious, you look at his hands too and you think – or at least I thought – monkey paws.

I put “massage” in quotes because what we actually see him doing is awkwardly sitting on her as if she were a tree stump, and grasping fistfuls of her flesh as if she were made of play dough. He squeezes, quick and fierce, then moves on to another fistful. He isn’t even symmetrical in his movements, but just sort of clutches at her randomly. You can see that she’s in agony – her body stiff even as she sighs and says “that feels so good.” Meanwhile he is staring down at his hands as if in shock at his own ineptitude. For a brief moment before the scene mercifully ends and the film leaves the horror genre behind and gets back to being hilarious, you look at his hands too and you think – or at least I thought – monkey paws. This morning I woke up and thought, “I must be wrong.” I remembered that there’s another massage scene in the Grant oeuvre, but I couldn’t remember where. I Googled it and, lo and behold, he gives Audrey Hepburn a foot massage in Charade. That scene has been put up on the intertubes, and it’s interesting – you can hardly see him massaging her feet and my bet is that it’s because Stanley Donen, the director, decided to chop the film off and spare his audience the sight. It’s been fourteen years since I Was a Male War Bride, and Cary Grant still can’t give a massage. He clutches at Hepburn’s feet with quick, hard squeezes, as if they are a rope he is climbing.

Perhaps he was repelled by Ann Sheridan, and perhaps by Hepburn too. Perhaps he couldn’t stand to touch them. But even if that were true, he was an actor. Pretending was his job. And Cary Grant was certainly familiar with massage: look how comfy-wumfy he looks here, receiving rather than giving. That’s Doris Day, by the way, another superstar of Code-era films. Doris Day, whom Oscar Levant knew “before she was a virgin.”

Perhaps he was repelled by Ann Sheridan, and perhaps by Hepburn too. Perhaps he couldn’t stand to touch them. But even if that were true, he was an actor. Pretending was his job. And Cary Grant was certainly familiar with massage: look how comfy-wumfy he looks here, receiving rather than giving. That’s Doris Day, by the way, another superstar of Code-era films. Doris Day, whom Oscar Levant knew “before she was a virgin.” One final piece of evidence. Grant’s third wife, Betsy Drake, tried to deny that her ex-husband was gay by offering up the following piece of information: “When we were married,” she said, “we were fucking like rabbits.”

Of course she meant that they had sex all the time, and I’m happy for them. But as an English professor and a prurient so-and-so, I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a deeper meaning to the metaphor. I will spare you any of the many videos available online that reveal how lepus curpaeums has sex. Suffice it to say, there is no foreplay, there is a quick piston-like action, and the lady bunny can quite easily continue doing whatever it was she was doing before the gentleman bunny got on board. Chewing lettuce, etc. You don’t really want rabbit sex to be your high-water mark for fun in the sack.

Of course she meant that they had sex all the time, and I’m happy for them. But as an English professor and a prurient so-and-so, I can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a deeper meaning to the metaphor. I will spare you any of the many videos available online that reveal how lepus curpaeums has sex. Suffice it to say, there is no foreplay, there is a quick piston-like action, and the lady bunny can quite easily continue doing whatever it was she was doing before the gentleman bunny got on board. Chewing lettuce, etc. You don’t really want rabbit sex to be your high-water mark for fun in the sack.OK. So. Three pieces of evidence. That’s what we need, isn’t it, to make an historical truth claim? 1. Grant’s career was strongest at the height of the Code; he made a great asexual hero. 2. He gave horrible massages. 3. His ex-wife compared him to a rabbit.

Sigh.

But truth schmuth, right? Who cares. I don’t actually want to time travel back and jump Cary Grant’s lovely bones. We don’t watch movies or read novels or have daydreams because we care about that miserly little thing called truth. Not even one little tiny bit. Cary Grant is still my fave. He’s still the most handsome, the most hilarious, the most brokenly perfect. In fact, I feel a Cary Grant film festival coming on. Arsenic and Old Lace? Amazing. The Philadelphia Story? Maybe even better than His Girl Friday. North by Northwest . . . oh my God. I mean, the man was incredible.

But truth schmuth, right? Who cares. I don’t actually want to time travel back and jump Cary Grant’s lovely bones. We don’t watch movies or read novels or have daydreams because we care about that miserly little thing called truth. Not even one little tiny bit. Cary Grant is still my fave. He’s still the most handsome, the most hilarious, the most brokenly perfect. In fact, I feel a Cary Grant film festival coming on. Arsenic and Old Lace? Amazing. The Philadelphia Story? Maybe even better than His Girl Friday. North by Northwest . . . oh my God. I mean, the man was incredible. I just wish I hadn’t watched I Was a Male War Bride last night. I wish I didn’t have that sneaking suspicion. I wish I could get those paws out of my mind.

Published on July 30, 2013 10:49

June 5, 2013

Bonnington Square -- An American Time Traveler in London

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073743103 0 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} a:link, span.MsoHyperlink {mso-style-priority:99; color:blue; mso-themecolor:hyperlink; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} a:visited, span.MsoHyperlinkFollowed {mso-style-noshow:yes; mso-style-priority:99; color:purple; mso-themecolor:followedhyperlink; text-decoration:underline; text-underline:single;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> <style><!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073743103 0 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> <br /><div class="MsoNormal">Recently I was asked to write a piece about Britain and why my time travel novel, <i>The River of No Return</i>, is set in that country rather than in my own.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It was a curiously difficult piece to write.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>I’ve now spent nearly two decades shacked up with a Brit, I’ve lived in England for years on end, I’ve done the usual reading of novels that either romanticize or despise it.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It’s a complicated place for me. I ended up deciding to write about Britain as a fantasy space, and if you’re interested you can read that piece, here:</div><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://thepenguinblog.typepad.com/the... style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><table cellpadding="0" cellspacing="0" class="tr-caption-container" style="float: left; margin-right: 1em; text-align: left;"><tbody><tr><td style="text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-B608y9-kJTU..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-left: auto; margin-right: auto;"><img border="0" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-B608y9-kJTU..." height="200" width="176" /></a></span></td></tr><tr><td class="tr-caption" style="text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: inherit;">David Young</span></td><td class="tr-caption" style="text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><br /></span></td></tr></tbody></table><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;">But before I wrote that piece, I found myself thinking back to the first time I lived in London, when I was twenty years old.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>Back when Britain really was brand new to me.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It was an amazing six months, partly because of my beloved English professor David Young, who took me and twenty other Oberlin students to London. He introduced us to the theater, but more than that, to good living and a certain relaxed relationship to intelligent conversation . . . he showed us that a life of the mind is a life of joy. </span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-1vSSqWfukOY..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: right; float: right; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-left: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-1vSSqWfukOY..." height="131" width="200" /></a>But my semester was also magical because of the accident of where I lived during those months<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"></span>. Ten other Oberlin students and I were crammed into an old Georgian row home in Bonnington Square, in Vauxhall -- a London neighborhood on the south bank of the Thames.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>We were all English majors, and we were spending a semester taking a class on the history of the “masque” and going to as many plays as we could fit in. </span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;">It was an incredible semester, and Bonnington Square was at the heart of it.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>The old 18<sup>th</sup>century Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens -- so notorious, so perfectly naughty, and now dwindled to nothing but a bare, dock-infested expanse of lawn -- were 100 meters away. We used to walk across that scrubby green and wonder if the sex, the thrills, the theater of the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens had soaked into the earth, or whether they were gone –dissipated into the sky.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></span></div><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><div class="separator" style="clear: both; text-align: center;"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-PN2MrU6e3sI..." imageanchor="1" style="margin-left: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-PN2MrU6e3sI..." height="252" width="640" /></a></span></div><style><!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-font-charset:78; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:1 134676480 16 0 131072 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Cambria; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073743103 0 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-font-family:Cambria; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:"MS 明朝"; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:Cambria; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.25in 1.0in 1.25in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> <br /><div class="MsoNormal">A new garden – Bonnington Square Garden – was being crafted on our doorstep.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It had been a bomb-site, and then a wasteland of stinging nettles -- now neighbors were coming together to make it into something rich and wondrous.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>Our neighbors to the left were squatters with the most amazing sense of style -- we watched as they transformed their house from a Georgian ruin into a grungy, post-industrial palace.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>An array of caravans painted with mysterious symbols turned up each month at the full moon, disgorging druids and witches – apparently a “ley line,” an ancient path that some said was a source of magical power, ran through Bonnington Square.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>Down the road the Bonnington Square Café, which had started as a squat café and which served up rib-sticking vegan treats by candlelight, drew us in at lunchtimes, and we would stay all day, wondering if there were anywhere like this, anywhere at all, in America.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-6l0ozZJpHQA..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; float: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-6l0ozZJpHQA..." height="320" width="225" /></a>We adored Bonnington Square.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>My friends and I, rolling out of bed late after a long night at the theater and then in the clubs, where we dressed like fallen angels and danced until we saw god, used to sit on the steps drinking our coffee and watching the square.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>There the squatters would come, heaving some talismanic metal object they had found in the defunct marble factory around the corner, or discarded on the street.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>There was the community coalition, digging in their patch of bomb-scarred earth.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>A druid leaned against his caravan, sucking on a cigarette and watching us through narrowed eyes.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>His girlfriend stuck an arm out a tiny open hatch, and he passed the cigarette through to her.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-IceRlrMOeSQ..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: right; float: right; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-left: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-IceRlrMOeSQ..." height="300" width="400" /></a>It felt as if history were unhinged here in this little square, as if everything that had ever happened was being remade and repurposed, and even we had our place in it – for weren’t we the 18<sup>th</sup>century pleasure seekers, so young and flamboyant, who came here from afar to a fleeting, lantern-lit masquerade, our eyes dazzled by fountain shows and fireworks, intent upon nothing more than play and dalliance?</span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>I found myself thinking about Bonnington Square again as I wrote <i>The River of No Return</i>, which is a big, genre-mash up of a time travel novel, set largely in London.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It’s part spy adventure, part sci-fi epic, part romance – and although my characters never go anywhere near Vauxhall, either in 1815 or in 2013 – the novel is also part Bonnington Square.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span><span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span></span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><a href="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-SAClCE6Mruk..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: left; float: left; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-right: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-SAClCE6Mruk..." height="200" width="131" /></a><span style="font-family: inherit;">In <i>The River of No Return</i>, the characters travel through time on currents of human emotion.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>My time travelers, who all share a rare talent, are able to move with the undertow of human feeling below the still surface of the present. My characters are dislocated in time by the violence of war, and they try, perhaps fruitlessly, to rebuild beauty from the wreckage.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>Because my characters exist in many various times, they have a somewhat Robin Hoodish attitude to property and to wealth.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>And because they are dislocated, adrift, they are masqueraders, seeking what pleasure they can grasp from the always disappearing world around them, and from the warm, willing “naturals” who live their lives from day to day, without ever suspecting that time is malleable and that history itself is up for grabs.</span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;">If the ley lines and the squatters and the bomb garden and the pleasure gardens are all to be found threaded through <i>The River of No Return</i>, so is joy.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>I have spent many semesters in London since then, but none of them so perfectly delightful.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>As a scholar and a historian I have spent countless days thinking about the way that the past penetrates the present, but I have never experienced it with such picaresque sparkle as I did across those six months.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>I wrote the novel to make myself happy – I intended to make a big cake layered up with the many pleasures of many genres and with the voluptuous details of many eras.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>And I did make myself happy!<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>But perhaps I was simply remembering a happiness I already knew, writing a chronicle of that one, perfect semester in that one, magical square.</span></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><br /></div><span style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;">Bonnington Square – like the rest of London – has changed enormously since 1992.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>But it is still itself.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>It hasn’t been uprooted and destroyed.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>The squatters are still there.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>You can watch a video about them here:<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span><a href="http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyl... style="font-family: inherit;"> </span><br /><div class="MsoNormal"><span style="font-family: inherit;"><a href="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-FP09aJ00UsE..." imageanchor="1" style="clear: right; float: right; margin-bottom: 1em; margin-left: 1em;"><img border="0" src="http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-FP09aJ00UsE..." height="257" width="320" /></a><span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>The café is still there.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>The garden is still there.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>Gentrification has happened and yet Bonnington Square has managed to maintain itself, at least partially, as a space that exists slantwise across that superhighway to bourgeois appropriation.<span style="mso-spacerun: yes;"> </span>And I am so very grateful that I got to be there, fleetingly, like a ghost, for a brief moment long ago.</span></div>

Published on June 05, 2013 09:37

February 10, 2013

The Next Big Thing in Books, or, Passing the Buck!