Isham Cook's Blog: Isham Cook

August 10, 2025

The Tao of Poison. A novel.

A poisonous maiden, a Daoist sex cult, and a violent anti-government rebellion.

Polyandry—one or more males moving in and sharing the wife’s bed with her husband’s consent in exchange for money or labor—was common among the impoverished in Imperial China, though illegal, and the polyandrous Yan family in rural Shaanxi Province take in two carpenter brothers. When one brother is convicted of murder after killing their neighbor in a dispute, a constable threatens to expose the family’s rumored polyandry and extorts sex from their beautiful 17-year-old daughter, Qiezi. Having grown up in the mountains, Qiezi has a preternatural knowledge of botanical medicines. She’s also addicted to the psychoactive, poisonous datura flower, and the toxins in her system are fatal to the constable. Now on the run as a murder suspect, she leaves a trail of sexual carnage wherever she goes. But a larger cataclysm awaits her when she gets caught up in the White Lotus Rebellion (1796-1804), which caused the deaths of 200,000 rebels, government troops, and civilians. Picaresque action, dark humor, and irony unfold in this visceral and cinematic novel.

Historical note: The Tao of Poison is extensively researched, including the author’s own travels to the scene of the rebellion in the Hubei-Shaanxi-Sichuan region to soak in the environment. Several novels have been published on the much better-documented Taiping Rebellion (1850-64) in China. This is the only novel in English on the White Lotus Rebellion. The sole Chinese novel on the rebellion, Wang Zhanjun’s The White-Clad Warrioress [Baiyi Xianü] (1982), was not used as a basis for The Tao of Poison. My inspirational model would have to be Patrick Süskind’s Perfume.

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

Chapter 1: The poison maiden

Chapter 2: The haunted pagoda

Chapter 3: The bath

Chapter 4: The nunnery

Chapter 5: Purple Cloud Palace

Chapter 6: The obscene temple

Chapter 7: The Magu goddess

Chapter 8: The apothecary shop

Chapter 9: The inquest

Chapter 10: The bandits

Chapter 11: The executioner

Chapter 12: The ring of fire

BUY THE BOOK:

Amazon paperback

Amazon Kindle

Link to bibliography of research for The Tao of Poison

* * *

MORE FICTION BY ISHAM COOK:

Lust & Philosophy. A novel

The Exact Unknown and Other Tales of Modern China

The Kitchens of Canton. A novel

The Mustachioed Woman of Shanghai. A novel

October 10, 2023

“The golden ocean flower.” Fiction

[For background to this story, read the preceding story “Qiezi.”]

A cleaver and a silver tael given to her by her father were all that weighed down the sack hanging from her shoulders as Qiezi forded the river. Now on the opposite bank on agile feet she scarcely needed to halt her pace except that she was hungry, the family meal aborted by the unfortunate events of the past hour. Expressionless yet alert, darting like a cat, she stopped and squatted to turn over the undersides of rocks and logs for termites and grasshopper and darkling beetle larvae to place on her tongue. They would do for now and she washed it all down with sweet osmanthus flowers and dandelions, stems and all, and river water from cupped hands. The sustenance glowed inside her and she got her energy back. As it grew dark, she slowed her pace and listened. The forest was almost cacophonous in its myriad sounds. The way she angled her head suggested they appeared to her as images positioned in a three-dimensional ink painting, with darker strokes in the foreground and lighter strokes in the background. There were no human figures in the painting; had there been, she would have removed them by repositioning the painting.

Her knowledge of the territory quickly brought her to where she wanted to go, a familiar clump of bamboo stalks. They ranged from her upper arms to her calves in diameter and she felled the thickest of them, wielding her cleaver like an ax with a few blows on either side. Hacking the tops away and shaving off the branches, she worked from memory, reconstructing what she had observed on the river.

She must have felt fortunate indeed even to be able to observe anything on the river, for she was the only grown girl in the village allowed to wander alone, the only woman apart from her mother who was physically capable of wandering alone rather than carried on someone’s back or hobbling along with a cane. Those villagers who hissed and snickered at her ugly “duck feet” wouldn’t last a day out here alone. Had she had a normal upbringing, I expect her mother had told her, she might have been of some use married off to a wealthy man. With proper lotus feet, she could have driven him to ecstasy by removing her bandages and letting him smell her odiferous stubs as he washed and caressed them in rose water, or not even wash them before taking them one by one into his mouth, like the male actors in opera troupes are rumored to do with each other’s members, and then stick that long big toe of yours into his filthy hole so he could be taken like a woman, a pleasure more delirious than taking a woman and available only to wealthy men. That’s the only good thing lotus feet are for and that’s how you might have been of some use. As for the other village girls, their lotus feet would find no male orifices to work their way into, no purpose apart from the brutal one everyone understood but never acknowledged: to keep you and your broken feet bound to the spinning wheel and the loom. How lucky you and I are to be mountain women!

Having lined up enough poles on the ground to match in length her height with arms extended and half as much in width, Qiezi lay down exhausted and fell asleep, cleaver in hand.

In the morning she dragged the poles down to the riverbank and lined them up flush, the straightest in the middle. From the soil along the eroded bank she pulled out the long thin roots of a pine tree and used these to tie two short bamboo poles crosswise to the parallel ones, looping them over and through and yoking them together as tightly as she could, into the semblance of a raft, if only it would work. Hooking it to a thick tree root with more root cord, she pushed the raft into the water. It floated. She tried climbing aboard but it tilted and she fell off. When she managed to board it, her weight submerged the raft below the water. She needed more poles, more tightening, more work, but her hands were numb and bruised. She foraged again for sustenance and rested. The day was already spent. The overcast sky would soon shroud her in pitch darkness, preventing travel down the river in any case. It would have to wait for moonlight.

The next day she cut two more lengths of bamboo stalk and added one to each side of the raft, while loosening the cords and readjusting the poles to fit yet closer together. It could not but work this time. The sky was clear and the moon was out. She got on the raft, but what she had not counted on was the extra weight from her sack, as light as it was, and the steering pole. The raft held—just below the water’s surface. She cursed and gazed back toward the bamboo grove. Further widening the raft meant another day’s work—and lost time. Grimly she stared ahead and pushed off anyway.

The current was strong enough to move her along at a good pace. But it also caused her to turn in circles and get stuck along the banks. She got better at controlling the raft with practice but steering it was even harder than building it! Her arms were about to give out when she discovered she could zigzag down the river by letting the raft drift until the bank loomed up and then pushing off again. After several hours, a drumbeat in the distance signaled the start of the fifth watch. She was approaching the walled town: the danger zone. It’s unlikely the nightwatchman and his lantern would notice anything but that possibility had to be minimized. As she approached the bend of the river and the dock just beyond, she aimed toward the river’s far side, placed the steering pole beside her and lay back flat on the raft, half in the water. No frightful voice called out and she coursed past.

In a few hours it would be dawn. Sleep was out of the question. She had to keep an eye on the raft. There was also the matter of where to ditch it. Traveling in daytime made her visible. On the other hand, the further she went the more anonymous she would be. But she was also in unfamiliar territory. At some point she would have to make her way among people who didn’t know her. She would be no less safe than if they did know her, given general hostility toward the unheard-of phenomenon of a young woman traveling alone. There would be only one recourse, to patch together a robe and shave her head to look like a Buddhist nun. She must have been wondering about her parents, who were escaping south on foot and should already have made it into Sichuan by now. They knew people there and would manage. She would manage. But as prepared as she was for surviving alone, she was nonetheless still in shock, a stunned creature drifting on a raft.

The dawn brought mist and shrouded the river. She heard voices but couldn’t see them and they were looming up. A man screamed. “Look, she’s floating on the water,” he said. “It’s a ghost, gliding on the water!”

“No, it’s not a ghost, you idiot,” said another. “She’s pushing a raft. See, it’s just under the water. She’s sitting on a raft.”

Their sampan came into view. “Who are you?” they said.

“Who are you?” said Qiezi.

“Your raft isn’t holding up. You need help. Here, we’ll help you.”

“No, I can manage.”

“You made this raft yourself? It won’t last another hour.”

“I’ve been on it since yesterday.”

“It won’t last, I’m telling you,” said the first man. He was young and stared at her open-mouthed.

The other man looked several decades older and was bearded and his hair had a Taoist topknot. “Where are you going?” he said.

“Ankang.”

“Ankang, in that? You’ll never make it! The river widens up ahead and you’ll flounder and drown.”

“You know the area?”

“Of course. We live here.”

“I need to find a place to stop off and rest.”

“Come on our boat and join us. Just let the raft go. It’s useless.”

“No, it’s my raft.”

“Let her hitch it to the boat,” said the elder. “Come in the boat and dry off. You’ll get sick in the water like that. Are you hungry?”

“Yeah.”

“Get her some fish cakes.”

“Thanks. I need to get to Ankang.”

“We can take you halfway there. To Flowing Water. From there you can keep going downriver or go by land.”

“How far to Flowing Water?”

“About a day.”

“Overnight?”

“Yes. You can sleep with us,” said the younger.

“Don’t frighten her. He means you can use our mat. We’ll leave you alone. You can rest now if you want. We’re busy fishing.”

“I don’t want to get off in the town. Is there another place you can drop me?”

The elder laughed. “Of course, such a beautiful girl alone in public isn’t safe. But how can you survive all by yourself?”

“I’m from the mountains,” she said between bites of fish cake.

“A mountain girl. What’s your name?” said the younger.

“Mantuoluo.”

“Mantuoluo. What kind of name is that? A tribal name?”

“Yeah.”

“I thought so. Your dark complexion. And your unbound feet. Are you Miao? From Sichuan?”

“Yeah.”

“What are you doing alone?”

“That’s my business.”

“Family trouble, I bet,” said the elder.

“We can take her to the pagoda.”

“What pagoda?”

“There’s an old abandoned pagoda on the way to Flowing Water. You can shelter there.”

“That sounds good.”

“You look exhausted. Lie down under the shelter and rest. We should reach the pagoda before the first watch this evening,” said the elder.

“You sure I’m not taking you out of your way?”

“No. We cover this whole area.”

Qiezi curled up on the dirty straw mat, her sack hooked through her arm, and fell instantly to sleep.

She had been out for who knows how long when singing startled her from her slumber. She looked around in confusion. The sun was on the other side of the sky; she had drifted off for most of the day. The younger was humming a tune.

“Oh, she’s awake,” said the elder.

The younger turned to her and sang:

When the beauty was here, flowers filled the hall.

Now the beautiful woman’s gone, the bed lies empty;

Only the rolled-up embroidered quilt sleeps there.

It’s now three years and I can still smell her scent:

A scent departed yet still lingering,

A woman departed yet not returning.

Yearning yellows the falling leaf,

White dew beads the green moss.

“What are you singing?”

“A poem, called ‘Long Yearning.’ Haven’t you heard of it? You must know it. It’s by Li Bai, the famous poet from the Tang Dynasty.”

“How would I know that?”

“You don’t know any poetry?”

“Of course, she doesn’t know any poetry,” said the elder. “What mountain girl can read?”

“I can read.”

“How can you read? I can’t even read,” said the younger.

“How do you know poetry then?”

He tapped his head. “It’s all in here. Memorized. I hear poems and remember them.”

“Where did you learn to read?” the elder asked Qiezi.

“The apothecary taught me. But he didn’t teach me poetry.”

“Really.”

“You must be very smart,” she told the younger.

“I can’t read and even I know poetry,” said the younger. “But you can read and you don’t know any poetry. I can teach you. Here’s another poem. It was written by the Huizong Emperor in the Song Dynasty for his concubine:

Drinking wine together in the glow of the nephrite lamp,

I think back on our embrace, it felt so good. But it hurt, oh it hurt.

I gently pushed him away.

The younger grew more animated as he spoke, mimicking the lines with bodily gestures:

Now I hear him tremble and I blush with shock.

We thrust up against each other.

We become crazy, together as one, arms clasping, lips meeting, tongues entwining.

“I don’t understand,” said Qiezi.

“That isn’t poetry,” chuckled the elder.

“Fuck your mother. It’s a famous poem! Now here, let me demonstrate it. Stand up. I’ll recite it again and show you.” The younger embraced her. “Now push me away when I say, ‘I gently pushed him away.’”

Qiezi pushed him away. The younger pretended to tremble and shudder, rubbing and grabbing his groin. He then threw his arms around her and tried to kiss her. As Qiezi repelled him again he grabbed her shirt and her breasts slipped out.

“What are you doing!” she gasped, pulling her shirt down.

“You’re not playing your part! You have to continue. You have to kiss me with your tongue,” he said.

“Who says I want to play your part?”

“He’s just playing with you,” said the elder. “Relax.”

“Yeah, don’t worry,” the younger said with a laugh, sitting down. “I’m just joking with you.”

“You’ve both been drinking.”

“Here, have some spirits,” said the elder, handing Qiezi his bowl.

Squatting with them, she took a sip. “That was very rude of you,” she said to the younger. “Don’t do that again.”

“What? Now, hold on. You’re telling us what to do? After rescuing and feeding you?” yelled the younger, standing up.

“That’s not the way to behave toward a young lady, raising your voice like that,” said the elder. “Use gentle words.” He went back to gutting the fish they had snagged. “Just play along with him. Though of course, he does have a point. You should show some appreciation for our generosity,” he continued, running the blade of his cleaver along her shirt, splitting the seam and opening it along the side. “These rags of yours are barely holding up. You need a new set of clothes.”

“They’re all I have,” she said, holding her shirt in place.

“What did we just tell you about showing some appreciation? Take your hand away!” said the younger, ripping Qiezi’s shirt open. He also had a cleaver—hers, she realized, taken from her sack.

“We’ll get you a new shirt back in town if you stay with us. And these pants too,” said the elder as he hooked the edge of the cleaver under her sash.

“Please don’t cut my sash. I’ll take it off.”

“Let us help you.” The elder proceeded to sever her sash and pull her pants down off her hips, before tossing her clothes in the water, along with her sandals. “You won’t be needing these anymore. Now that’s more like it. A wild mountain girl in her natural state.”

The younger was already leaning back under the shelter with his pants down. Qiezi removed a fresh bloody tube from between her legs, squatted over him and the elder in turn. When they were finished, they told her to stay put under the shelter.

“When will we reach the pagoda?” she asked.

“Who said you’re going to the pagoda?” said the elder. “Don’t you want your new set of clothes?”

“Can’t you just let me off at the pagoda?”

“Can’t you just shut up?”

“You said you would. I’ve been cooperating with you.”

“She’s starting to get annoying,” said the younger. “You’ll be lucky if you make it as far as the pagoda. Should we tell her?”

“Tell her what?” said the elder.

“You know, that we have to kill her.”

“That’s hardly been decided. We may have some use for her. At least until tomorrow.”

“I want to be of use to you. I can cook for you. I can gather all kinds of vegetables and herbs.”

“Who asked your opinion?” said the younger, slapping Qiezi in the face. “She’s already a nuisance—a dangerous one. We’d better kill her now.”

“I’ll scream.”

“So what? No one will hear you.”

“Someone surely will. It’s only early evening. My body will be discovered downstream and you’ll be prime suspects when you dock.”

“She can’t be seen with us on the river,” said the younger.

“That’s only a problem in the daytime,” said the elder. “I’d like to have another go at her tonight. Such a precious creature. We’re not going to find the likes of her again.”

“Why don’t you take me to the pagoda and leave me there? You can tie me up so I won’t escape. You can do anything you want with me.”

“I told you to shut up!” said the younger.

“Keep your voice down. People may hear us,” the elder admonished him. “Let’s keep her for a few hours while I think about what to do. No more word from you,” he warned Qiezi, pointing the cleaver at her, while the younger guarded the other side of the shelter. “Or we’ll send you and your raft adrift after slitting your throat.”

“I’m not going to cause any trouble—”

“Didn’t we just tell you to shut up?”

“Yes, you did. But I’m not afraid of you. Let me join you. As a fisherwoman. I want to learn about that. I can teach you about foraging.”

“Hold it!” said the elder. The younger was about to strike Qiezi with the cleaver. “Not one more word out of both of you! Take the pole and steer for a while. But go slowly,” he told him.

The sampan hovered on the water as darkness gathered.

“Here, you take the pole. I’m feeling tired.” As the younger reached over to hand the elder his pole, he tripped and fell.

“What’s the matter with you?”

“I don’t know. I feel sort of dizzy.”

“I don’t feel very good myself. Was that a bad batch of fish cakes?”

“They’ve been okay until now.”

“I don’t have any more strength either. Let’s lay low and tie up the boat at that bank over there.”

The two men stayed where they were, immobilized.

“Let me help you,” said Qiezi, taking the pole herself and stepping onto her raft.

“Get back under the shelter, if you don’t want us to kill you.”

“I think it’s the other way around.”

“Whadd’ya mean?” said the younger, lifting up his head from the floor of the boat, his speech slurred.

“You should be grateful you have someone to bury you.”

“What are you talking about? Who are you?”

“You wouldn’t understand.”

“What’s happening to us?”

“You were right, she’s a ghost,” said the elder. “Where are you taking us?”

“To the pagoda.”

“No! It’s haunted! Take us to the Buddhist temple.”

“Where is that?” said Qiezi.

“Ten li further downstream. This side of the river. You can see it through the trees. Help us!”

“You won’t make it that far,” she said to him.

The elder’s eyes widened in shock. “You’re a spirit from the haunted pagoda!”

He crawled after her with the cleaver. Qiezi knocked it out of his hand with the steering pole, sending it into the water. He flopped onto the raft and drowned, his face in the water. This forced her off the raft and into the water. She climbed onto the sampan, smacking the younger on the head with the pole until he released his grip on her leg.

He continued to moan incoherently as the naked girl pushed down the river looking for the pagoda. By the time she spotted it, he was silent.

Qiezi lashed the raft and the sampan to a tree by the riverbank and gathered the remaining fish cakes and cleaver. The elder’s body was the heaviest and it took all her effort to drag him up the footpath and into the pagoda. The younger’s body was lighter, but as she pulled him over the sampan’s edge she slipped and cut her foot on a sharp rock in the water. Her foot bleeding profusely, she managed to get the second body into the pagoda. She went back down to the water to clean her foot, grabbed two more items, the steering pole and the elder’s flask of spirts, and dragged herself back to the pagoda, careful not to soil the gash. She then stripped the corpses of their clothes. The younger’s she wore. The elder’s she spread out on the stone floor to lay on, while tearing off a strip to tighten around her injury to staunch the bleeding. Her back to the wall, she poured the strong spirits on the wound and waited for the bleeding to stop, gobbled down the remaining fish cakes, and sobbed herself to sleep after the long day.

In the morning, she hunted for medicines. She was looking for the three-to-seven-years plant, so named for the time it took to mature, shavings from whose ginseng-like root placed on the wound would heal it fastest. This was not at hand, so the more abundant crow’s head would have to do, whose purple-hooded petal resembled the prepuce over her own yin button. It was so poisonous she had to grab it by another plant’s leaf to avoid contact with her fingers; lightly as a feather she passed it over her gash. As there was no time to weave a new pair of sandles—both men had been barefoot—she grabbed several taro leaves as big as lotus leaves, wrapped them around her foot and secured them with root string. Now a bit more ambulatory, using her bamboo pole as support, she looked around for more essentials, one in particular, her loadstone the golden ocean flower, needed to keep her mind clear; the last of her supply had been hastily tossed off the sampan. If she could find the yellow celestial seeds flower with its eerie blood-red veins or the human-shaped root of the even rarer mandela flower, which itinerant doctors sold at outrageous prices, they would also serve, but none did she see.

Back at the river, Qiezi got in the sampan after separating it from the raft and headed downstream. Soon she ran into another pair of fishermen, haggard-faced types who drew up alongside her, dispensed with niceties and reached over to drag her into their sampan. She slammed her cleaver down on the boat’s edge, missing a wrist but lopping off a finger. As the man squealed in pain, with a surge of energy she swung her steering pole around and smacked the other man hard on the groin, and pushed off against their boat. Fired by adrenaline, she sped through the water. Their sampan stayed away. Eventually she spotted the temple. Securing her boat at the bank, she limped up the path.

She entered the courtyard. No one was about the modest compound. Perhaps the monks were out begging for alms, or in lunching or napping. It was early afternoon. She peered into the nearest hall. A tall young monk was sweeping. At first he waved her away. Looking more closely, he came up and stared at the strange young creature with a bamboo pole, horrid rags drooping from her and foot wrapped in leaves. “What do you want?”

“Something to eat,” said Qiezi.

“You can’t eat here. Go to the women’s monastery.”

“I’m in a bad situation. Just give me something to eat and I’ll leave. And I need a robe.”

“What happened to you?”

“I was attacked by fishermen down on the river.”

“Whose clothes are these?”

“Never mind.”

“You’re so young. I thought you were an old beggar woman. I’ll get you a bowl of soup but you can’t stay here.”

“Don’t tell anyone I’m here.”

“I have reason enough not to tell anyone. Go wait outside the gate.”

Her hands were still shaking from the latest encounter on the river as she downed the soup.

“How bad is your foot?”

“I know how to take care of it. Please, I need a robe.”

“There are no robes here for women.”

“Any robe is fine. You can see these clothes won’t do.”

“Go to the women’s monastery.”

“I have something to tell you. This has to be a secret. There are two dead men up the river. I can show you where they are.”

“Oh heavens. I’ll go summon the yamen runners and you can lead us there.”

“No. Only you.”

“Why? What—did you kill them?”

“No. I found them dead. Would I be telling you about them if I had killed them?”

“This is a matter for the yamen runners.”

“Come with me now or I’ll run away and you won’t find the bodies.”

“Are you crazy? They will be found without you and you’ll be the prime suspect. You’ll be caught before you know it, assumed guilty and tortured.”

“Come with me now. I’ll show you where they are and I’ll be gone. We can take the sampan upriver.”

“Whose sampan?”

“Get me a robe and come.”

“Are you dangerous?”

“Do I look dangerous?”

The two of them paddled upstream and tied the sampan at the bank by the pagoda.

“The haunted pagoda!” exclaimed the monk.

“You really believe that? Go up into the pagoda and wait for me. I need to wash my foot. Give me the robe. I want to change into it.”

“Don’t change here. You might be seen.”

Qiezi glanced toward the river. “Go up and wait for me.”

He stayed where he was and watched as she waded into the water and submerged herself, scrubbing her hair. What then emerged was no longer the grubby vagrant but something yet more distressing and unfamiliar to his eyes. The baggy fisherman’s clothes now clung to her like seaweed, and he saw her round hips and bulging bust, and with her disheveled hair slicked back and out of the way, the finest cheekbones, a face of classical perfection, a woman of exceptional beauty. As she lifted her arms to squeeze the excess water from her hair, her wide sleeves dipped open to expose black flames of armpit hair as obscene as anything between her legs. And as she bent down to look at her foot, he glimpsed a hanging breast and its brown nipple through the gap in her shirt.

“Let me see the wound,” he said.

“It’s not getting any worse. I’ll tear more strips from these rags to bind it. Now give me the robe.”

“You’d better change in the pagoda. It’s safer there. I’ll stand outside.”

They entered the pagoda. The monk went up to the naked corpses laid out side by side in the center of the floor; they were intact and there were no signs of mischief.

“This is where you found them?” said the monk.

“I found them in the sampan and brought them here.”

“I wonder if they were poisoned. But arsenic usually blackens the flesh. Their flesh has yellowed a bit, that’s all. How did you discover them?”

“You saw that raft down there? That’s what I was on and I found them drifting in their boat yesterday, already dead.”

“I thought you said you were attacked.”

“I was, this morning on the way to your temple. Another boat of two fishermen. I sliced off one of their fingers when they tried to rape me. I’m afraid they’re going to come back looking for me. If you ever see a fisherman with a missing finger, you’ll know it’s them. Let me change into the robe.”

“What kind of person are you, attracting so much trouble? Are you a spirit? A fox spirit? A witch? Are you real? Change here and let me confirm you are human!”

“Give me the robe.”

He was holding it to his chest and breathing heavily. He extended it to her then pulled it back before she could take it.

“Give me the robe.”

He was breathing so hoarsely he was snorting and losing the power of speech. “No!” he blurted out, more to himself than to her. Shifting his gaze from her to the floor and back to her, he flung the robe down and spread it out, tears dropping from his eyes.

“No, you’ll die!” she said. “I’ll tell you the truth. I am poisonous!”

“How can you be poisonous?”

“I poisoned those two men. That’s how they died!”

“How can you poison me? You can’t poison me. I won’t let you!”

A stronger power had taken over his limbs. He tore open her shirt, stripped her of her pants, and dragged her onto the robe.

“I’m telling you, you will die!”

A witness to this scene looking through one of the pagoda’s windows, had there been one, would have seen a streak of sunlight illuminating the ripped deltoids of a man as he folded back female legs and dug his face between them like a tiger feasting on its prey, silent but for his grunting. He mounted her and worked up to his final spasm before collapsing upon her in sleep. She kept him inside her.

He woke up sometime later. The sun was still out but dusk was gathering. “I have to go. You be out of here soon, before the yamen runners come.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Tired. Drained.”

“No, don’t leave me.”

Her legs were wrapped tightly around him, preventing him from getting up.

“Let me go. What we’ve done is shameful, terrible, and I have to return to the temple.”

“Stay with me a while.”

“What’s your name?”

“Mantuoluo.”

“Mantuoluo? The ocean flower?”

“Yes, the golden ocean flower.”

“That’s not your real name. Why did you name yourself that?”

“I need it. The ocean flower. Have you seen any around?”

“I recall seeing some purple ones, but I can’t remember where. Why do you want it? It’s poisonous.”

“Purple ones, yellow ones, white ones, they’ll all do. I need it. My body is saturated with it.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I’ve eaten the flower all my life, since I was old enough to go out and wander as a child. I almost died the first time I ate it. But it opened my eyes and I’ve never been without it. I can’t stop eating it.”

“How can that be? How can you eat a poison?”

“It’s not a poison in small amounts. It’s a medicine, and it’s magical. But I’ve eaten so much of it over the years I need more and more. I can’t die from it. I will die without it.”

“What’s magical about it?”

“The plant spirits come to life. They talk to you.”

“Let me go. I have to get back.”

Her legs were still clamped around him and her yin muscles contracted and gripped his member within. “You won’t make it. It’s too late.”

“What do you mean?”

“Let me comfort you in your last hour.”

He looked at the corpses and back at her, only now understanding, his eyes widening in horror. “You only slept with them and they died?”

“Stay with me. Love me. Can’t you feel my desire? Can’t you feel how wet I am? This is now the apex of your life, with me. Your life’s work is now complete. Appreciate it! Appreciate me!”

“Why are you doing this to me!”

“You forced me. I told you you would die. You didn’t listen.”

“You seduced me.”

“You wanted me.”

“You’re a witch!” He stood up with her still attached to him. “Get off me!”

“I am not a witch. But you’re going to die. You have to come to terms with it. You can’t run away. You’ll soon collapse. I’m sorry! Let me attend to your body here in the pagoda.”

He managed to dislodge the human-sized insect and they both fell on the floor. “No!” he shouted, breaking down in tears. “I don’t want to die.”

“I’m sorry, but that’s your fate.” She wiped the streaming perspiration off his face.

“I have to get back to the temple. I can’t be abandoned here!”

He got up. Grabbing his robe, he staggered down to the river, fell into the sampan naked and tried to push off. She went after him and watched sadly as he got nowhere. “You have to untie the boat.”

“I’m losing strength. Take me back to the temple.”

“It’s too late. If you flee in the boat, you will only drift in circles and no one will see you. Come back to the pagoda.”

At the water’s edge Qiezi sat down with knees pulled up to watch him die. As he slipped into unconsciousness, she donned his robe, grabbed the cleaver from the sampan and, using the water’s surface as a mirror, carefully shaved all the hair off her head. She had to make another trip to the pagoda to clean, dress and bandage her foot. She wrapped his body in the other robe, the one he had spread out on the floor, after washing out the blood and semen stains. With its sash she was able to cinch him up the path and into the pagoda. She placed his body next to the other two. His penis was still erect—a death erection.

Now she was a Buddhist nun, if only in appearance. She didn’t know much about the creed aside from cursory visits to temple fairs with her parents. But she knew that even bad people tended to leave nuns alone. The river was a different matter. The sight of a solitary nun in a sampan would have been so odd word would travel fast; and she had had enough dealings with fishermen. She would have to make do on injured foot; reed sandals would be made later. She still had her silver tael, cleaver, and a bowl filched from the sampan in her sack, soon fill up with edibles and medicinals gathered in the woods along the way, worn under her robe.

* * *

MORE FICTION BY ISHAM COOK:

“Qiezi.” Fiction

The Exact Unknown and Other Tales of Modern China

Lust & Philosophy. A novel

The Kitchens of Canton. A novel

The Mustachioed Woman of Shanghai. A novel

May 14, 2023

Insights into China (Part 3/3): A stay in a hotel

A budget hotel chain in Shanghai; the scrolling text beneath advertises a discount (all photos by Isham Cook)

A budget hotel chain in Shanghai; the scrolling text beneath advertises a discount (all photos by Isham Cook)Ramshackle inns and sailor bars

The first hotel I stayed at in China was the Seagull in 1990, across the street from the famous Astor House established in 1846 (now the China Securities Museum), in the former American Concession in Shanghai. It’s been a while and the only thing I recall about the hotel is having to hand my key over to a floor attendant manning a desk in the hallway whenever leaving my room. Also in the hallway was a rack with multiple copies of a booklet translated into English on the correct interpretation of the “Tiananmen Incident” in Beijing the previous year. Stationing attendants on every floor made it difficult to smuggle unapproved guests into your room, particularly Chinese nationals of the opposite sex. But apart from these quirks, even by then China could be said to have come a long way in bringing its hotels up to minimally acceptable standards.

It had only been a few years since individual tourists from abroad, as opposed to chaperoned groups, were allowed into the country at all. In fact, travel to China for either employment or tourism purposes had petered out back at the start of World War Two under the Japanese occupation. For over fifty years, until around the time of my visit, China was a closed country.

Seagull Hotel circa 2020, viewed from the former Astor Hotel

Seagull Hotel circa 2020, viewed from the former Astor HotelIn the four decades prior to that, going back to the turn of the twentieth century, if you were not lucky or wealthy enough to reside in the foreign concessions of Shanghai and other port cities or Beijing’s Legation Quarter, conditions in the sailor bars and the few other establishments willing to put you up would have been pretty makeshift. The film The Sand Pebbles (dir. Wise, 1966), based on Richard McKenna’s naval sojourn in 1930s China as fictionalized in his novel of the same name, gives us a vivid idea of what these conditions might have been like. Another useful eyewitness account is the writer Qian Zhongshu’s catalog of ramshackle inns in his novel A Fortress Besieged (1947) chronicling protagonist Fang Hongjian’s journey from Shanghai to a university teaching job in Hunan Province in 1937. Travel conditions at the time were hardly less primitive than in pre-modern China. The scarcity of buses and trains meant it took weeks to cover the same terrain traversed today in several hours by high-speed train, and Qian satirizes the naivety of his pampered hero and his travel companions who failed to plan ahead and bring along enough cash. The colorful details, however, derived from the author’s own experiences traveling around southern China in those same years. Qian’s acutely observed descriptions are of documentary value and thus serve as a rough baseline for assessing China’s progress in its hospitality industry over the subsequent half-century. One inn is described as follows:

The two Chinese-style, single-storied buildings in the back were divided by wooden panels into five or six bedrooms. A tent, which served as a dining room, was erected on the bare earth in the front. The hotel relied on the aroma of wine and meat, the banging of knives on pans when the food was ready, and the cries of the waiters to draw travelers in to spend the night. The electric lights inside the tent were dazzlingly bright. The bamboo and mud-plastered walls were completely pasted over with red strips of paper on which were written the names of the best dishes of the house.

Another inn also had their kitchen set up in the entrance:

The front room served as the guests’ dining room during the day and as the bedchamber of the innkeeper and his wife at night. The back room was divided into two guest rooms which were shut off from the sunlight and exposed to the wind and the rain…All around the inn was the heavy stench of urine and excrement, as though the inn were a plant for which it was the guests’ duty to provide fertilizer and irrigation. The innkeeper was frying food on the street.

In one inn, tea and rice were sold on the ground floor, while guests accessed their rooms on the second floor by a bamboo ladder. To provide an extra bed for a third guest, “the waiter placed a door plank across two unpainted wooden benches.” The beds were infested with lice and bedbugs and mice scurried over the guests in the dark. In yet another inn, they “all slept in an unpartitioned room. There were no beds, just five piles of straw. They preferred the rice straw to hotel beds, which sometimes felt like a relief map and sometimes like the chest of a tuberculosis patient.” Not all was dreary, and entertainment of a sort could be had: “The walls of most Chinese inns are very thin, and though one’s body may be in one room, it seems as though one’s ears are staying next door. As usual, the inn had blind, opium-smoking women soliciting business from room to room and inviting guests to pick numbers from Shaohsing operas for them to sing” (trans. Kelly & Mao).

If we go back further in time to the Qing Dynasty, conditions for foreign travelers fell into two phases. In the first phase (1636-1860), from the Dynasty’s outset (and long before that) until the Second Opium War, foreigners were forbidden from setting foot in the country on pain of execution. A handful of Jesuit missionaries and foreign delegations on diplomatic embassies were the sole exception. Upon the conclusion of the First Opium War in 1842, foreigners were permitted to reside in the foreign concessions of five treaty ports, Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. In the second phase (1860-1901), from the Second Opium War until the Boxer Rebellion, foreigners were finally allowed to travel outside of the treaty ports and into China’s interior, though travel conditions were primitive and dangerous. Cities and towns were mostly walled and were typically loathe to let you in. You pitched your tent outside the city wall and hoped you wouldn’t have to resort to your guns if pelted by stones; to travel without firearms or hired guards was suicidal. If you managed to slip into a city you had the rabble to deal with. The English traveler Isabella Bird has dramatic accounts in The Yangtze Valley and Beyond (1899) of twice being saved at the last minute by local garrisons coming to her rescue from mob lynching — they tried to break right into her room in the inns she stayed in. Her main offense was being a woman, but all foreigners were subject to attacks. Inns were either wretched hovels with paper windows poked open by peeping Toms or dirt spaces shared with animals.

Budget chain hotel in Shanghai, 2023

Budget chain hotel in Shanghai, 2023To be sure, classier accommodation was available to local men of means, primarily for liaisons with in-house courtesans and prostitutes; there is a description of one such establishment in Pearl S. Buck’s novel The Good Earth (1931). And the concessions, of course, particularly in Shanghai and Beijing, had world-class hotels for the foreign elite.

After the atrocities against foreigners in the Boxer Rebellion, the Chinese Government enforced greater safeguards for travelers throughout the realm and things gradually improved. The history of travel, hotels and inns in pre-modern China has yet to be written, though I take a stab at it in my Chungking: China’s heart of darkness. In that essay I provide plentiful examples of the challenges that confronted foreigners on the road in the nineteenth century, which make China in our day and age, even back in the 1990s, a utopia to travel and reside in, despite one significant problem that distinguishes the Chinese hotel experience from that of other countries. In most of the world today, hotels do not discriminate against certain categories of guests. In China, by contrast, hotels perform a gatekeeping function and indeed discriminate against certain kinds of guests. This will be illustrated below as I take the reader on a tour of Chinese hotels over the past three decades.

“It’s for your safety”

To return to that initial trip of mine in 1990, after Shanghai, we headed for Nanjing (I was traveling with a male Japanese friend). Motorcycle rickshaws ferried us from our ferry at the Yangtze River pier to the only hotel in the city that accepted foreigners, or as they put it, the only hotel that was appropriate for foreigners, the Jinling Hotel at USD $80 per night, rather pricier than we had budgeted for. After being given the same unwanted royal treatment in our next destination, the Jinjiang Inn in Chengdu, we investigated the surrounding streets and found the equivalent of a backpacker hotel, though backpacking wasn’t yet a concept in China; scraggly backpackers looked to the Chinese like poor people, and they couldn’t understand where the vagabonds came from since foreigners by definition were rich. They agreed to put us up only because we caught them off-guard. Foreign travelers were still so rare that no rules or guidelines were in place and they didn’t know what to do with us. The room had a missing shower curtain and a stopped-up toilet (the maid handed me a plunger) but at only USD $4 per night we couldn’t complain. Late that night the room across from ours resounded with partying Chinese. They left their door open and in the morning we espied them asleep on the floor amidst empty beer bottles. We found a similarly low-end hideaway in Guangzhou (Canton), though that city was an exception in having a history of contact with foreigners: the hotel restaurant had coffee and a Western breakfast on its menu.

Not long after starting my job as a university lecturer in Beijing in 1994, I was invited by a female student and two male friends of hers on a trip to Harbin in northeast Heilongjiang Province. I accepted, eager to explore a new part of the country. We arrived at dawn after twenty-two hours on the overnight train and breakfasted on beef noodle soup in the restaurant of a hotel that wouldn’t accept me because I was a foreigner. The next five hotels we tried also wouldn’t accept foreigners. We finally found a state-run hotel that wanted to charge me four times the local rate. The receptionists were sufficiently impressed with my “Foreign Expert” card (provided by the government to foreign teachers with at least a Master’s Degree) that we were able to bargain the price down somewhat. Our female companion, however, was not allowed to room with us and we had to pay for two rooms. (She incidentally years later became a notable news talk show host on national TV; for reasons of anonymity you’ll have to take my word.) They insisted on holding on to my passport for our entire stay, for the sake of my “safety.” This was actually unlawful on their part, I later found out, as foreigners were required to carry their passports on them at all times. These safety measures in any case didn’t apply to our rooms, as ours was broken into during the night and 400 yuan lifted from one of my companion’s wallet.

Five-star international chain hotel, somewhere in China

Five-star international chain hotel, somewhere in ChinaThere are three phrases foreigners in China quickly learn: “There is not” (mei you), “Not okay” (bu xing), and “For your safety” (weile nin de anquan). We heard these phrases a lot, especially the first two; sometimes they were the only responses we could get from the service staff. Upon arriving in our next city, Changchun in Jilin Province, the first few hotels we tried again wouldn’t accept foreigners. Typically, a receptionist would disappear into a back office to speak with the boss (who wouldn’t deign to deal with us directly) and return after an unaccountably long absence — fifteen, twenty minutes — but always with the unimaginative reply, “bu xing.” The northeast was looking pretty grim. I have to give my companions credit for their patience, as they then called every hotel they could find in the phone book at a cigarette stand with a public phone. We were about to give up in despair when the man running the stand pointed to a small unmarked building across the street, an unlicensed hotel, which accepted us without so much as checking our IDs. A tiny foyer served as the lobby and had a refrigerator, a train timetable tacked on the wall, and the famous Richard Avedon poster of a giant boa wrapped around a naked Nastassja Kinski on another wall. The friendly proprietor put us together in a dormitory-style room with bunk beds for USD $12, after asking the three women occupying it if they wouldn’t mind moving to a smaller room. They were clad in tight jeans and attractive and one of them gave me the eye as they squeezed passed us with their towels and toothbrush kits. I suspected they were itinerant sex workers and this hotel was where they stayed when they weren’t with customers. We had better luck the next night in Shenyang in Liaoning Province. A private hotel operator greeted us as soon as we exited the train station and led us to a nearby hotel, no questions asked.

Later that year I toured Xinjiang and Gansu Provinces in China’s northwest with Ming, a new female Chinese companion. This was an enlightening experiment in another form of hotel gatekeeping: two people of opposite sex rooming together. In Kashgar near the Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan borders in Xinjiang’s far west, we took a chance on the People’s Hotel. They accepted me but predictably wouldn’t let us room together. The bunks in the dormitory rooms were only USD $1.80 each, with a single grimy shower room down the hall (hot water available only between 9-10 pm). Ming had a lower bunk in her room; a rat fell onto the woman in the upper bunk. The next day across from an enterprising outdoor patio restaurant for backpackers, John’s Cafe, which had acceptable banana pancakes, we discovered the Seman Hotel, where foreign travelers were more in evidence. But they were absolutely not going to allow us two to room together. A strange dialogue with the receptionist ensued:

Steampunk-themed lobby with cafe in Ningbo hotel, 2023

Steampunk-themed lobby with cafe in Ningbo hotel, 2023“Are dorm beds available?”

“Yes, but they are for the foreigners.”

“How much for the men’s dorm?”

“We only have one dorm room since it’s the foreigners’ custom for men and women to sleep in the same dorm room. So I’m afraid you’ll have to sleep there together.”

The dorm space was a spacious and sunny corner room looking out on greenery. Twelve thin futons were laid out on the blue-carpeted floor. We placed two of them side by side to form a single bed. The other occupants were male backpackers from the U.S., Canada, and Australia, and one guy from the UK bed-ridden with a case of giardia picked up in Pakistan. Most of the Western backpackers were en route to or from Pakistan via the scenic Karakoram Highway. A few Pakistani merchants kept to themselves in private rooms. The shower stalls were clean and hot water was available all day, though as they were located in the men’s washrooms, female guests had to clear us out before locking the door behind them.

In Kuqa, a Uyghur-predominant city near the Kirzir Buddhist grottoes where cannabis grew wild in the streets, we were allowed to room together. In the grape-growing oasis of Turpan, the sole guesthouse we found had issues with our cohabiting, so Ming tried a new tack and simply asserted that we were married. They asked to see the evidence. She said she didn’t have it on her. They shrugged their shoulders and gave us the room. In the Hui Muslim city of Linxia in Gansu Province, the receptionist of the third hotel we tried, once we had tracked her down, couldn’t be bothered with paperwork and gave us a room without even registering us. In the Tibetan-predominant city of Xiahe, a mini Lhasa also in Gansu, the Labrang Hotel was clean and attractive though prim, and they put us in separate rooms. Laura, a Chinese-American doctoral student researching traditional Chinese medicine we met on the bus tagged along and agreed to share Ming’s room. We partied it up in my room with a bottle of brandy I bought from the hotel bar. Laura decided to hit the sack early. Ming stayed in my room. We forgot to bolt the door and in the morning the maids barged in. It may not be the custom for many people but I only sleep naked and so do the women I shack up with. I’ve never understood how people can sleep with clothes on. Anyway, at the sight of me, the maids vanished before I even made it to the door to lock them out. Later that day we decided to make a united front at reception and demand we be allowed to room together for our final night. They confronted us first, only to ask us if we wouldn’t mind rooming together since they were short of rooms and wanted to accommodate a new guest.

From top: Friendship Hotel (front building), 1994; the author’s wing, living room, and bedroom (twin beds instead of a queen-size bed were provided seemingly to prevent any improper behavior)

From top: Friendship Hotel (front building), 1994; the author’s wing, living room, and bedroom (twin beds instead of a queen-size bed were provided seemingly to prevent any improper behavior)The Friendship Hotel

Foreigners working in Beijing had long lived in the Friendship Hotel, where the authorities could keep a friendly eye on them. The huge hotel complex, co-built with Soviet help in the 1950s, was featured in the memorable film M. Butterfly (dir. Cronenberg, 1993), based on the true story of a foolish French diplomat (played by Jeremy Irons) who falls in love with what he believes to be a female Chinese opera singer but who is actually a male Dan (female) role performer, as well as a Chinese spy who betrays him. The story is set at the outset of the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) when most of the remaining foreigners living in China were declared personae non gratae and deported; the handful allowed to stay were a select group of regime-friendly writers and media personalities. Foreigners began to trickle back into China in the 1980s. The Friendship Hotel is where my university put me up in the mid-1990s. It’s an instructive case of what a longer residence in the country was like during those years. It was in the early ’90s in fact that visiting rules slowly began to ease. Prior to my arrival, I was told, visitors to the hotel had to register twice, first in a guard post at the outer gate where they were queried on the purpose of their visit and again at our building’s entrance.

By the time I arrived, the rules involving visitors were in flux and involved perpetual guesswork. Visitors were no longer stopped at the guard post but could proceed directly to our section of the hotel. In the foyer just inside our building was a desk where one of the maids was usually on duty to monitor guests and duly recorded their ID number and contact information in a register. But they often weren’t there and guests breezed right in. There were times when the staff knew I had a female over in the evening and times when they didn’t know. I didn’t push things. As they gave me some slack by looking the other way, I observed a certain etiquette in getting any women out in the morning before the maids arrived to clean my room. One day I met a Chinese woman named Shasha who lived on the floor above mine with an American editor at an English-language Chinese press. They were not married. Only the year before my arrival, she had brazenly decided to move in with him. Cohabitating outside of wedlock was still more or less illegal, but the Chinese are wary of scandals involving foreigners and the hotel put up with Shasha for a week or so before summoning the police. It turned out she was something of a virago, already well known to the authorities for her pro-democracy activities, which included operating a democracy-literature bookstore cafe in the ’80s; she had been arrested during the Tiananmen Square crackdown and spent several months in jail. Her notoriety worked in her favor. Regarding this new business as petty, the police ordered the hotel to let her stay put. In other words, the era of relative freedom I encountered at the Friendship Hotel was largely due to the precedent set by Shasha.

Foreign guests, however, were a distinct species, officially on the books and you couldn’t sneak them in. It was illegal, and still is, for a foreigner to reside anywhere in the country without registering either with approved accommodation or the police. What this means is that if you are living in an apartment in China and have someone visiting you from abroad, you are expected to march this person down to the local police station and humbly ask the cops for permission to let them stay with you, even just for a night. Nobody does this of course but it is the law. And it would put you in an awkward position if you were to actually do so, for the police might choose to make things difficult, say by requiring a letter from your workplace vouching for both of you, and until you get that letter your friend stays in a hotel. Or they might refuse outright on the grounds that you aren’t legally qualified to assume responsibility if your friend were to get into trouble. Thus when a Japanese female friend visited me for a week-long stay at the Friendship Hotel, I was in a bind. I wouldn’t have been able to pull off hiding Eri in my apartment, so I duly registered her with her passport at the hotel’s foreign affairs office. They told me she had to book a separate room at regular hotel rates. Moreover, I would not be allowed to stay overnight with her. This was needless to say unacceptable. That evening when we returned to my wing after dinner, several hotel managers were waiting at the building entrance for a showdown. I told them Eri was staying with me. They said she was not allowed. I got my supervisor at the university on the phone and he was able to resolve things (we are still good friends to this day). In fact, the hotel couldn’t have cared less about the morality of cohabiting, it was the breach of protocol that was the problem. When my supervisor agreed to assume responsibility for the arrangement, saving their face, they departed with a sigh of relief.

The next university in Beijing I taught at several years later was less relaxed about protocol. The Foreign Experts Guesthouse was on campus. All visitors had to sign in and out at the entrance and there was a strict 11 pm curfew. If it got close to the hour, they would knock on my door to inform me it was time for my guest to leave. An old male friend from the U.S. once visited me, and even though I had an extra bed they made him put up in a vacant suite and charged him the going rate of USD $30 per day, claiming with the usual refrain it was for my “safety.” Where our safety was not of much concern was the padlocking of the building’s front door every night. Although a guard slept in the office at the entrance, a hasty evacuation might not have been possible in the event of a fire or earthquake.

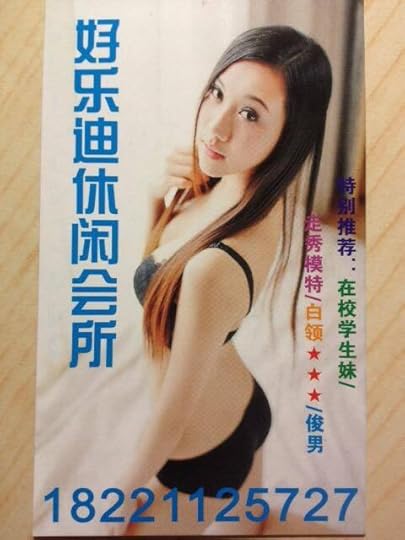

Flip sides of a prostitute service card. Left to right: “Holiday Leisure Club: fashion models / office ladies / hot men / custom recommendations / schoolgirls / 24-hr room service / printed receipts / safe, prompt, convenient. Call this hotline.”

Flip sides of a prostitute service card. Left to right: “Holiday Leisure Club: fashion models / office ladies / hot men / custom recommendations / schoolgirls / 24-hr room service / printed receipts / safe, prompt, convenient. Call this hotline.”

We have several paradoxes here. Foreigners were given star treatment in the best hotels, whereas ordinary Chinese would be stopped merely entering the lobby and questioned as to their business. Yet the strictest curfews applied to foreigners. Mostly these curfews were intended to shore up sexual morality — ostensibly anyway; a deeper, age-old fear was spying — yet most hotels had in-house prostitutes. The madam would receive word from reception of the latest male guests and call their room as soon as they checked in; others would go through a routine of calling every room one after the other (you could hear the phone ring in the room adjacent, followed by your room and the room on your other side). If a woman answered the phone, they hung up. Otherwise, it was, “How about a massage?” or “Are you lonely?” In other hotels, a prostitute followed you into your elevator and struck up a conversation. Or they simply knocked on your door out of the blue, sometimes a pair of them. Once in a Holiday Inn in Wuhan in 2004, I was having a drink in the hotel lounge and five women appeared out of a side room, surrounded my table and asked me choose one of them. When budget hotel chains such as Hanting, Jinjiang Inn, Home Inn, and 7-Day Inn popped up around the country later that decade, there was a crackdown on the more blatant practices and sex workers began to work more discreetly, though they were easily reached by their ubiquitous service cards slipped under guests’ doors.

The bathhouse revolution

Meanwhile, the bathhouse revolution had been gathering steam. This astonishing industry bore little relation to the benign camaraderie sentimentalized in the film Shower (dir. Zhang, 1999), which had a moderately successful international run. In the 1980s and earlier in the communist era, bathhouses served strictly as public showers when apartments lacked hot running water. In his City of Lingering Splendour: A Frank Account of Old Peking’s Exotic Pleasures (1961), John Blofeld depicted the more lavish trappings of bathhouses in the 1930s. In the 1990s, this tradition was revived. At first, they were two-story structures, with separate male and female bath areas on the first floor, the male section typically including a hot water pool, and a coed “public hall” (da ting) on the second floor where both sexes dressed in pajamas could mingle freely and sleep overnight on lazy-boy recliners while watching kungfu flicks on the hall’s movie screen. Waiters served tea, beer and snacks, and massage girls were on hand to do foot massage. There were also private rooms with varying numbers of beds, where individuals or groups could sleep in greater privacy, get a full-body massage with a handjob, and in some establishments, paid intercourse. The key thing was that there was never any registration process and anyone could occupy the private rooms (though the doors were not always lockable). They were thus the only place unmarried lovers could shack up; they also served as transient hotels for those who for whatever reason did not want their whereabouts to be known (see The old Chinese bathhouse, circa 2000).

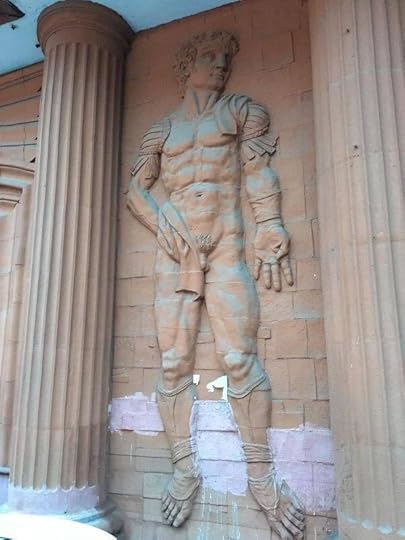

From top: bathhouse in Harbin, 2000s; relief statue from the bathhouse’s facade at lower left (the uncharacteristically drab exterior of this bathhouse belies the luxuriousness inside); multi-story massage venue in Beijing catering to straight men, circa 2020.

From top: bathhouse in Harbin, 2000s; relief statue from the bathhouse’s facade at lower left (the uncharacteristically drab exterior of this bathhouse belies the luxuriousness inside); multi-story massage venue in Beijing catering to straight men, circa 2020.Around the turn of the century, bathhouses grew in size and luxuriousness, elaborately decored with Greco-Roman themes and other iconography suggestive of Western decadence. One bathhouse I visited in Harbin in the 2000s (pictured) boasted, in the men’s bath section, a large hot pool lined with gold plating and several smaller pools of differing temperatures and colors steeped in a variety of medicinal herbs. In addition to the usual public hall, there was an auditorium with live northeastern-style vaudeville known as errenzhuan; one performance I saw hired skimpily dressed Russian dancers. Buffets grew more sumptuous and compared favorably with those of five-star hotels. Some bathhouses were able to tap into underground hot springs. The Chinese are often stereotyped as lacking in creative imagination; not so the bathhouse industry. There is quite simply nothing of the like in the West, except perhaps the great European spas, but the latter are only preserving a long tradition rather than inventing themselves out of whole cloth as in China. In the 2010s, bathhouses kept evolving into such rarefied exclusiveness that I found myself priced out of them. If you have extra cash to throw around, they would make a good research project to investigate now.

Around 2003, the government suddenly allowed unmarried couples to room together in hotels across the country, no questions asked, provided both registered at reception with valid IDs. This applied to foreigners as well. And then around the time of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, they clamped down on the freewheeling bathhouses and required all those staying overnight to register with their ID, just as in hotels. For a time, receptionists were lax about tracking visitors who snuck in later to stay with you so that they wouldn’t have to register, while daytime visitors were trusted to vacate your room before bedtime. Then in the 2010s, hotels began providing electronic card keys, and you couldn’t go up to your floor in the elevator without swiping your card. At the start of the present decade, hotel registration tightened up considerably, sparked by Covid-19 epidemic measures. No guests or visitors could get past reception without a health code reading on their cellphone indicating they had tested virus-free within the past 48 or 72 hours (or had not traveled from a Covid hot zone). In post-Covid 2023, QR codes are dispensed with, but the registration process remains strict and uncompromising. All hotels now have a national ID scanner for domestic guests, who are also photographed with a webcam at the reception desk. Foreigners all have their passports carefully checked (visa as well as latest entry stamp), scanned and photocopied and their faces recorded by webcam as well. This applies to every person rooming together. As I discuss in Sexual surveillance in the Covid-19 era, though couples who are not married to each other are free to room together, the government now knows exactly who is committing adultery, information which may be of potential interest to certain parties. Also, since the “group licentiousness” law was revamped in 2012, hotels may inform the police if three or more people not of the same sex occupy a room together (families excepted of course), if that is, the hotel allows them to room together.

A very special excursion

In November of 2022, while living and working in the southern Chinese city of Ningbo and travel-starved, the university where I was teaching hastily arranged a group excursion for us to the mountainous city of Ninghai fifty miles to the south. Almost the entire university got to go on the trip. Many buses were involved, and those of us assigned to the same bus were informed by a community representative to be packed and ready to leave and wait for a phone call that evening. I didn’t get the call till 2:30 am and was then told to wait for another call to come a few hours later or sometime in the morning. I didn’t get the second call until noon: our bus was waiting at the gate. It soon filled up with colleagues living in my complex. The drive down to Ninghai was quite nice, actually, and what we could see of the city was green and attractive. The hotel was in an old building but the room was sufficient for the purposes of a week-long stay. Our tour of the city was confined to what could be viewed out the window. Except to retrieve our three daily meals and have our temperature checked twice a day at 6 am and again at 6 pm by workers in white hazmat suits, we were not allowed outside the door of our rooms. As I’m used to daily walking, I created an obstacle course around the room of thirty paces; 200 laps twice a day satisfied my exercise addiction. Alas, we were suddenly informed that our trip would be cut short and we were shipped back home after only three nights, though we were again forbidden from leaving our apartments for the next three days, and an electronic sensor was affixed to our doors to ensure this.

Ninghai hotel room and a boxed meal

Ninghai hotel room and a boxed mealOur bizarre little outing was carried out, as you may have guessed, as part of epidemic prevention measures. What triggered it was two students on campus who tested positive for Covid. The campus was immediately locked down and everyone connected to the university in any capacity, or who had been present on the campus within the previous two weeks — some 10,000 students, faculty and staff — were ordered onto buses and shipped to available hotels in Ningbo and surrounding cities (those living in the same building on campus as the two affected students were locked down in that building for a week). Married couples, inexplicably, were forced into separate rooms (their children were split up between them). Then just as arbitrarily, they decided that this massive relocation was unnecessary and we were allowed to go back home for self-quarantine. I’m glad I went through this historically instructive and enlightening experience, having a taste of what many millions of others around the country had to undergo more protractedly, such as the months-long, city-wide lockdowns in Wuhan, Shanghai, and other cities. This period has now passed, but its effects linger and spark speculation about the future of China’s hospitality industry. As of May 2023, the government has yet to start issuing tourist visas to foreigners. They will come in due time, but I wonder if part of the reason for the delay is deliberation about how exactly to treat the tens of thousands of expected foreign tourists and how the latter will take to being ordered to stare into a webcam lens fixed on the reception counter, children included, and how they will feel being subjected to a greater degree of surveillance than what they are used to back home; how foreign mixed-sex groups of three or more will take to being advised not to room together or by rooming together not to engage in any activities that violate Chinese law, such as occupying the same bed; or what reassurances they can be given that their private information will not be stored by the authorities or shared with third parties.

What does not appear to be showing any signs of change — I will not mince my words — is the repugnant practice of discriminating against foreign travelers by only approving certain hotels for their use. You do not know the degrading feeling until experienced firsthand, being told you can’t reside somewhere because you’re a “foreigner.” I’m sure they have their rationales for this, namely, there are bad elements out there who are eager to take advantage of you and thus “it’s for your safety.” Only designating certain hotels for foreigners also makes it easier for the authorities to track us. Granted, foreign tourists who travel to China generally won’t notice this problem if they book in advance or in a tour group since international travel websites already filter for approved hotels, and it’s not necessarily that great of an inconvenience. It’s the idea of it, an idea with a long pedigree in China’s history and is inherent in the very word for foreigner, waiguoren, literally “outside country person” or “outsider.” Imagine how your notion of this class of people would be shaped if you constantly heard them spoken of as “outsiders.” A commonly used colloquial term is laowai, literally “old outsider,” as in my “old” friend. Most Chinese know they shouldn’t use this term within earshot of internationals in their country since it is also slightly insulting and patronizing, yet the officially employed term waiguoren is no less problematic. Can any language escape this othering effect of whatever term it employs for “foreigner”? In English, we may speak of “foreign tourists” to distinguish them from domestic tourists, but we don’t regularly use the term “foreigner” by itself. The default assumption is that you are not a foreigner. When it’s discovered that you are a foreigner, then you tend to be labeled by your country — a Brazilian, Japanese, Chinese, and the like — instead of the alien category of “foreigner.” This more humanistic conception ought to start being a part of the public discourse in China.

Lobby of a budget chain hotel in Beijing

Lobby of a budget chain hotel in Beijing

* * *

Other posts of interest by Isham Cook:

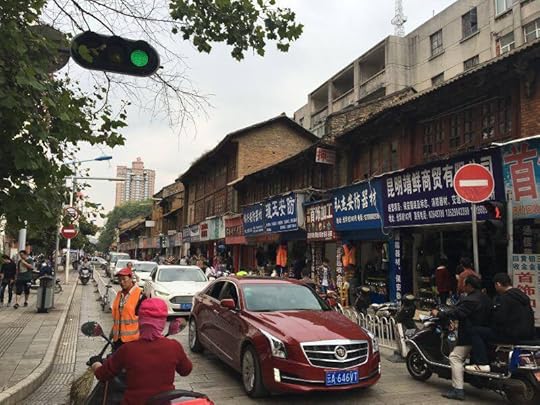

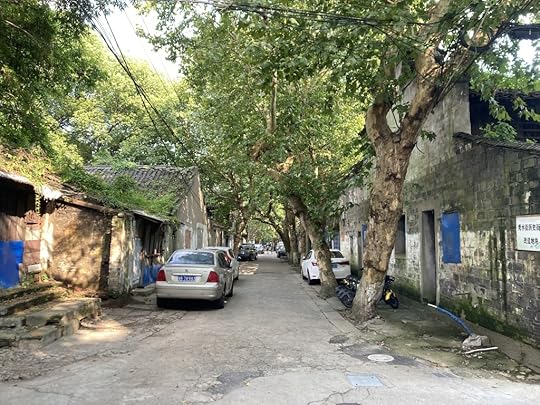

Insights into China (Part 1/3): A walk down the street

Insights into China (Part 2/3): A visit to a restaurant

Sexual Surveillance in the Covid-19 era

Chungking: China’s heart of darkness

Why Airbnb ain’t my cup of tea

The old Chinese bathhouse, circa 2000

April 29, 2023

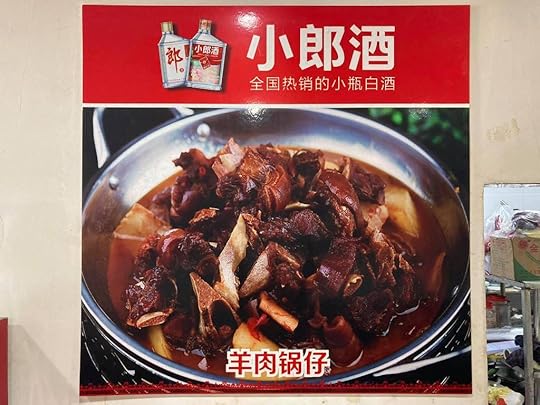

Insights into China (Part 2/3): A visit to a restaurant

Upscale Hangzhou cuisine in Beijing. The vertical banner reads: “Dragon Well Boat Banquet”

Upscale Hangzhou cuisine in Beijing. The vertical banner reads: “Dragon Well Boat Banquet”I begin with a textbook case of intercultural miscommunication I once witnessed in a university cafeteria in Beijing. Just as I was telling the server which dish I wanted, a female student standing next to me blurted out to him in Mandarin, “I told you I wanted the shredded pork noodles. Didn’t you hear me?”

Another student butted in between us to indicate what he wanted. The server served him first before walking several pans over to get my dish. This was logical enough; his pan was right in front of the server and mine was several paces away. But the female student was not happy about this and said to a friend standing behind her in fluent English, at which point I realized they were ABCs (American-born Chinese), “I can’t believe he’s walking away!”

Now it was clear they had a little war going on, as the server continued to ignore her. When I finished my meal fifteen minutes later, she was still standing there glaring at him.

You too would be upset if you were ignored by a cafeteria server. But that’s not what initially appears to have set things off. It could have been any number of things. I’d guess she had expected him to acknowledge her request with eye contact and grew peeved when it wasn’t forthcoming, he in turn found her to be rude, and it snowballed from there. I had dealt with this server many times and never had an issue with him. She was likely a new arrival in China, an exchange student a few months fresh off the plane, and her Chinese ethnicity wasn’t of much help as she negotiated her way around the cultural minefield. It was after all not the cook’s responsibility to explain how things worked; he was simply going about his job. She was the annoying anomaly. The moral of the story is that the fault for the communication breakdown lay squarely with her. The burden is not on the host country to explain it all to you; the burden is on you, the guest, to figure it out.

And then there was the incident back in the early 1990s when I had just arrived in Beijing to start a teaching job. It was actually my first restaurant to step into outside my new residence, the famous Friendship Hotel, when the number of foreigners in Beijing could still pretty much fit into a single hotel. The menu consisted of Chinese characters on typed white A4 sheets of paper stuck in grimy plastic sleeves (menus with photographs came later). I had studied some Chinese and could recognize 宫保鸡丁 and a couple vegetable dishes, surprisingly inexpensive at only 2-3 yuan a piece. I ordered a serving of potatoes and a serving of turnips, not sure how they would be cooked. The Kung Pao Chicken came first, filled to the brim with excess oil. Then the potatoes and turnips arrived — in raw slices. It took a moment to register why the vegetables were served raw. Oh, of course. They were meant to go with hotpot. But that’s not what blew my mind. The cooks, waitresses, and manager — the manager! — were standing by the door to the kitchen giggling at me. They had a good laugh at my expense, until I overturned the Kung Pao Chicken onto the tablecloth and walked out without paying. I heard shouting in my direction but they didn’t pursue me out on the street.

Noodle shop in Chengdu, 1990 (top); restaurant in Harbin, 1994: a ticket purchased at the booth is handed to the kitchen window for service (bottom)

Noodle shop in Chengdu, 1990 (top); restaurant in Harbin, 1994: a ticket purchased at the booth is handed to the kitchen window for service (bottom)They were not very nice. Other restaurants would have handled it better, patiently trying to explain to the clueless foreigner why I couldn’t order those vegetable plates alone. The verdict again, however, is that the fault lay with me. How were they supposed to know my motive in ordering the vegetables? Customers may order whatever dishes they wish for whatever reason, as long as they pay for them, and the restaurant is under no obligation to object.

Let’s turn things around and imagine you’re a Chinese customer in an American restaurant yelling “Waitress!” This is exactly how it’s done in China. You shout “Fuwuyuar!” at the top of your lungs so that your voice can be heard across the restaurant, ensuring that a waitress, any waitress, will promptly appear. It’s not considered rude at all. In the US, it would be so outrageous the restaurant might ask you to leave. And you would be wholly at fault for your ignorance of the country’s culture and etiquette.

(Not that, on the other hand, restaurants in our so-called civilized world are immune from bad management or worse. Don’t ever underestimate the depths to which the staff will stoop if they are not happy with you. In my teens, I once worked as a dishwasher in a steakhouse in Canada. When a customer sent back a steak for being too tough, the cook tenderized it by throwing it on the greasy floor and stomping on it before putting it back on the grill. We were all of us, including the cook, young and immature and thought it hilarious. But I knew it was wrong and hence it has stuck in my memory.)

Chinese restaurant culture today has massively evolved and is scarcely recognizable next to the functional proletarian interiors of three decades ago and their grinding and scraping metal chairs and fluorescent lighting and no decor but for a hastily tacked-on photomural of a tropical landscape, and the raucous patrons who tossed their chewed bones and cigarette butts on the concrete floor.

Nowadays, the more downhome restaurants, called jiachangcai (homestyle cooking) or nongjiacai (farmhouse cooking), are clean and comfortable in a homey way, reminiscent of the reassuringly ordinary American diner. Behind the cashier you can still find a generous selection of strong spirits (baijiu) for customers who want to party a bit since traditionally, though there are bars, there is no bar culture in China; restaurants are where people feel at liberty to get drunk. I usually just grab a beer by opening the glass-paned refrigerator that stands near the cashier and pulling out my brew of choice (the waitstaff duly note this and add it to the tab), as if popping open a beer out of mom’s fridge back home — and refreshingly doing away with our stilted “Would you care for something to drink?” ritual. The Chinese though seldom start off with a beer before eating. They sensibly order their drinks to arrive along with the food so that they’re not imbibing on an empty stomach.

Homestyle restaurant in Ningbo, 2023. I’ve removed the cellophane from the sterilized saucer, bowl and spoon set.