Kjerstin Gruys's Blog

May 4, 2017

Analyzing the Aesthetic Labor of High Maintenance Hair

Blog post originally published HERE. A few months ago the website Inc.com featured the essay "Why Women Who Want to Be Leaders Should Dye Their Hair Blonde, According to Science" as it's lead article. As a (blonde) sociologist studying how appearance shapes women's labor market opportunities I read the article with great interest. The research itself seems fascinating and important, but the coverage of it by writer @MindaZetlin is deeply concerning.

Blog post originally published HERE. A few months ago the website Inc.com featured the essay "Why Women Who Want to Be Leaders Should Dye Their Hair Blonde, According to Science" as it's lead article. As a (blonde) sociologist studying how appearance shapes women's labor market opportunities I read the article with great interest. The research itself seems fascinating and important, but the coverage of it by writer @MindaZetlin is deeply concerning.Zetlin over-extrapolates from the research findings presented by Dr. Jennifer Berdahl and Dr. Natalya Alonso, professors at the University of Columbia's Saunder School of Business, at the Academy of Management's annual meeting. Observing what seemed like an odd overabundance of blonde women in leadership positions, Berdahl and Alonso conducted a study with 100 men, to gauge their reactions to hair color. As summarized by Zetlin,

Asked to rate photos of blonde and brunette women on attractiveness, competence, and independence, the men thought all the women were equally attractive, but that the brunettes were more competent and independent. Then they were given photos of blonde and brunette women paired with a quote, such as "My staff knows who's boss" or "I don't want there to be any ambiguity about who's in charge." Suddenly there were big differences, with the brunettes coming in for harsh criticism, while the blondes were rated much higher on warmth and attractiveness.In a Huffington Post interview, Berdahl is quoted as saying "If the package is feminine, disarming, and childlike, you can get away with more assertive, independent, and masculine behavior." In other words, having blonde hair appears to help women more easily navigate the double-bind of being seen as either likable or competent. In my undergraduate Gender & Society course we discuss how overtly feminine appearance work – or “aesthetic labor,” when that work is tied to the labor market – might be understood as a form of “female apologetic,” a gender strategy commonly associated with female athletes who strategically embody traditional femininity as a way to symbolically make up for their participation in stereotypically masculine sports.

I can relate to this. My hair own is naturally blonde, and I've long had a gut sense that I get away with more in terms of non-conforming gender behaviors because of my conforming fair skin and light hair. Looking “girly” (a concept which, of course, is not just about gender presentation but also race, class, sexuality and age), can serve as a social buffer when behaving, well, manly.

Berdahl and Alonso's research suggests this gut sense isn’t completely in my (tow)head. I've had (usually female) students come up to me at the end of a course to share that they wouldn't have taken my class – much less feminism – seriously if I hadn’t been "cute" and "fun." I love hearing that my classes are fun and engaging, but I HATE being called "cute." Cute is for puppies, not professors.

Indeed, one downside to being "a blonde" is not being taken as seriously. I feel like I have to be consistently articulate and "sound smart" in my professional life to keep colleagues and students from seeing me as I'm dumb or shallow. In fact, during my first semester of graduate school I darkened my hair to brown because I thought I would be taken more seriously. I’m not sure it helped. Maybe it did, but it came at the cost of feeling like myself. These days I instead lighten my hair to a purplish platinum (and I always wear "statement" glasses) because I think it helps me look a little more edgy and LESS "cute." I feel like myself, but it took a lot of overanalyzing to get here.

Despite my annoyance with the "dumb blonde" stereotype, having straight blonde hair is a privilege that has helped me navigate many social and professional relationships more fluidly than other women, especially women of color. That said - I abhor Zetlin's suggestion that all ambitious women should lighten their hair. For one thing, the science supporting this contention is incomplete. Berdahl and Alonso's fascinating research has only examined men's perspectives on women's hair color. Given the gender diversity of today's workplaces - as well as evidence that women may make appearance-related attributions differently than men - it is a mistake to believe that only men's perspectives matter. Further, understandings of "good hair" are not merely determined along gender lines, but are matters of race, class, gender, age, and other intersecting privileges.

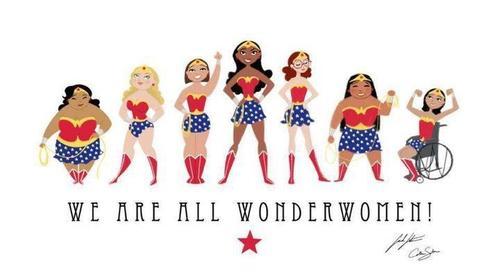

Image found here.For example, after presenting at an ASA panel on "Embodied Labor & Intersectional Inequalities" last summer, fellow presenter UVA grad student Allister Pilar Plater, and I discussed the observation that some professional Black women maintain chemically “relaxed” hair while climbing the corporate ladder, but transition back to their natural hair texture once reaching positions with greater power. What meanings and consequences come with natural hair for those Black women who choose it, and how are those meanings and consequences shaped by class status? The term “nappy” has often held shameful racist and classist connotations, but today the term has been reclaimed and embraced by some black women, from bell hooks who wrote the children’s boofk Happy to Be Nappy to the trending hashtag #NappyAndHappy. But can poor Black women claim #nappyandhappy in the same way as more privileged Black women? More intersectional research is needed before we can make confident claims about the multiple meanings and consequences of women's hair strategies (much less give proscriptive advice on what women should do).

The decision to "go blonde" or chemically “relax” hair incurs real risk alongside any potential upside. The expense, time commitment, and unknown risks of chemical exposure involved in high-maintenance hair color and/or texture might very well outweigh the social benefits any individual woman might hope to enjoy. Time, money and health are not minor sacrifices.

The upkeep of my own purplish platinum hair, for example, demands 2-3 hours of idle time every 6 weeks and costs more than my monthly gym membership. I justify it as an aspect of my "don't call me cute!" personal style, because time in the salon feels like self-care, and because it turns out that extremely damaged hair doesn't have to be washed as often as my natural hair texture (so I can make up for some of that time lost in the hair salon). I also believe – perhaps idealistically – that having purple-toned platinum hair is an expression of diversity rather than conformity (at least in the academy!), and that my visible non-conformity might have little consequence for me, while helping to make space for others. These are the things I consider in my most innocent personal calculations, but, of course, it is ultimately my class and race privilege that allow me to indulge in the considerable expense of "having fun with my hair" and "playing with color," while less privileged women – especially those whose natural hair color and texture are the opposite of mine – can neither afford such indulgences, nor are likely to find them quite so "fun" if they are pushed by the pressures of discrimination rather than pulled by the pleasures of aesthetic experimentation.

And here is where Zetlin is so wrong to say that, "women who want to be leaders should dye their hair blonde." Sure, there may be some sound personal "strategy" in doing so (alongside, of course, the risks), but viewing appearance discrimination as an individual problem that individual women should solve by changing their bodies is dangerously short-sighted. It's just one more "patriarchal bargain" that privileges some women (usually those already privileged) while perpetuating a fundamentally unequal system. SaveSaveSaveSave

Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on May 04, 2017 09:53

January 2, 2017

You Can Call Me ... PROFESSOR Gruys!

Hello Everyone and Happy New Year!

I have an exciting announcement to share: I've joined the Wolf Pack! As of January 1st, 2017 I've OFFICIALLY begun my new position as Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Yes, it's really happened! My graduate years (thanks UCLA!) and my post-doc years (thanks Stanford!) are behind me, and from this point forward you can call me ... PROFESSOR Gruys!

I have an exciting announcement to share: I've joined the Wolf Pack! As of January 1st, 2017 I've OFFICIALLY begun my new position as Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Yes, it's really happened! My graduate years (thanks UCLA!) and my post-doc years (thanks Stanford!) are behind me, and from this point forward you can call me ... PROFESSOR Gruys!

Over the next few weeks I'll be moving into my office at UNR and on January 24th I'll start teaching "Introduction to Sociology" and "Sociology of Gender." Next semester (Fall 2017) I'll teach a brand new graduate course on "Qualitative Research Methods." In this tough academic market I feel so blessed to have been hired to teach courses on topics I'm passionate about. And did I mention that my colleagues at UNR are some of the nicest (and smartest) folks I could have hoped to work with? Yes, indeed, life is good.

Come find me in my new OFFICE (not cubicle!) in Lincoln Hall.

Come find me in my new OFFICE (not cubicle!) in Lincoln Hall.

So, yes, Michael and I have up and moved to Reno. It was hard to leave San Francisco, but we're close enough to visit when we want to, and we're enjoying settling into our new home here (twice as big as our SF place and half the price!). The snowy winter weather is taking a little getting used to, but the ski slopes are helping with that adjustment.

As for the boring practical stuff, my new work email is kgruys@unr.edu, though you can still reach me at KjerstinGruys@gmail.com as well. My Stanford and UCLA email addresses, however, are no longer in service. If you want to snail mail anything to me (congratulatory chocolate bars, etc.), here's my work address:

Dr. Kjerstin GruysDepartment of SociologyMail Stop 300University of Nevada, RenoReno, NV 89557

And with that, I've got to get back to writing the manuscript proposal for my next book (more details forthcoming). I am, after all, officially on the "tenure track" so there's no time to waste. In the meantime.... Go Pack!!

I have an exciting announcement to share: I've joined the Wolf Pack! As of January 1st, 2017 I've OFFICIALLY begun my new position as Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Yes, it's really happened! My graduate years (thanks UCLA!) and my post-doc years (thanks Stanford!) are behind me, and from this point forward you can call me ... PROFESSOR Gruys!

I have an exciting announcement to share: I've joined the Wolf Pack! As of January 1st, 2017 I've OFFICIALLY begun my new position as Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Yes, it's really happened! My graduate years (thanks UCLA!) and my post-doc years (thanks Stanford!) are behind me, and from this point forward you can call me ... PROFESSOR Gruys! Over the next few weeks I'll be moving into my office at UNR and on January 24th I'll start teaching "Introduction to Sociology" and "Sociology of Gender." Next semester (Fall 2017) I'll teach a brand new graduate course on "Qualitative Research Methods." In this tough academic market I feel so blessed to have been hired to teach courses on topics I'm passionate about. And did I mention that my colleagues at UNR are some of the nicest (and smartest) folks I could have hoped to work with? Yes, indeed, life is good.

Come find me in my new OFFICE (not cubicle!) in Lincoln Hall.

Come find me in my new OFFICE (not cubicle!) in Lincoln Hall.So, yes, Michael and I have up and moved to Reno. It was hard to leave San Francisco, but we're close enough to visit when we want to, and we're enjoying settling into our new home here (twice as big as our SF place and half the price!). The snowy winter weather is taking a little getting used to, but the ski slopes are helping with that adjustment.

As for the boring practical stuff, my new work email is kgruys@unr.edu, though you can still reach me at KjerstinGruys@gmail.com as well. My Stanford and UCLA email addresses, however, are no longer in service. If you want to snail mail anything to me (congratulatory chocolate bars, etc.), here's my work address:

Dr. Kjerstin GruysDepartment of SociologyMail Stop 300University of Nevada, RenoReno, NV 89557

And with that, I've got to get back to writing the manuscript proposal for my next book (more details forthcoming). I am, after all, officially on the "tenure track" so there's no time to waste. In the meantime.... Go Pack!!

Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on January 02, 2017 13:43

October 24, 2016

Dear KJ: How Can I Overcome My Fear of Eating in Public?

Dear KJ: How do you get over your fear of eating in front of other people (at a restaurant or cafeteria, for example) after recovering from an eating disorder? (Originally posted HERE)

Image found HERE.The experience of having—and recovering from—an eating disorder takes many forms, because many different kinds of people experience EDs. Many eating disorder sufferers experience crippling phobias and obsessive thoughts related to eating and body image. One phobia many people have heard of is having extreme fear of certain foods, or food groups. Another commonly known experience is one of obsessive counting, whether counting calories, carbs or minutes exercising.Some less well-known fears, however, have to do with the social aspects of eating, which add an additional layer to an individual's struggles managing food or exercise-related symptoms. Eating is a social experience in most cultures, including in American culture. We see advertisements depicting big family meals as a time when people connect with each other at the end of the day. One of Normal Rockwell's most famous pieces features Thanksgiving dinner in this way. The common dating phrase "dinner and a movie" similarly links food with social connection, and pretty much every high school movie depicts the school cafeteria as a modern day Roman Forum! Suffice it to say, most of us associate eating with spending time with friends and family.But eating socially can be a huge challenge for people who are suffering from or in recovery from eating disorders. Sometimes, this challenge is due to attempts to hide disordered eating habits from friends and family. Sometimes, those struggling eat in isolation not only to be secretive, but also to avoid scrutiny, critique or feeling freakish. It's also common for individuals with eating disorders to experience exaggerated feelings of being watched or judged while eating.Once a pattern of eating in isolation has become a habit, the prospect of eating socially, or even of eating alone but in a public place, can trigger major anxiety, sometimes leading to panic attacks. Not everyone experiences this, but it's more common than most people think.There are many well-researched approaches to overcoming fearful experiences. In extreme cases, such as when a person experiences panic attacks or if the social phobia begins to extend beyond just eating situations, it's almost always necessary to work with a therapist with special training on managing phobias. For cases that are less extreme but still distressing, here are some tips. First, when in recovery from an eating disorder, your first priority must be to take care of your body, even if this sometimes means neglecting social experiences. If your body isn't properly nourished and rested, your brain can't work effectively. If your brain isn't working effectively, your efforts on the psychological side of recovery will be even more difficult.So, if nourishing yourself properly means missing out on a slumber party or two, so what? However, this only makes sense if you are actually able to nourish yourself in less social contexts. And it can't go on forever. At some point, whether it takes days or weeks or months, it's important to rejoin the social world of eating.There are two strategies I've used when facing a fear. The first one is to deliberately—and in all seriousness—ask yourself, "realistically, what's the absolute worst thing that could happen? How would I survive that?" (Note the choice of the word "realistically." That means you should avoid imagining scenarios of an asteroid falling on the restaurant, okay?)Once you've answered this question to yourself, come up with a plan to survive it. Notice I did not say "come up with a plan to guarantee that this never happens!" Facing fears by avoiding them is what trapped in this situation in the first place. So let's try it: maybe your worst case scenario is that somebody comments on your eating in a way that is upsetting, whether it's a difficult relative or a nosy stranger. What would you do to survive it? Is there a phrase you could prepare in response, like "I know you think that commenting on my eating is helpful, but it isn't. Please give me some space." Afraid that could be too difficult or awkward? What if your plan was to burst into tears and run out of the room? That doesn't sound fun, but could you survive it? Think to yourself, "Well, if I burst into tears and run out of the room I will probably feel really embarrassed, but I will survive. I will not actually be in any real physical danger." When I describe this strategy, some of my friends find it incredibly useful and calming to be so specific and methodological in their planning, but others find that it increases their anxiety to imagine possible worst-case scenarios. Only use it if it works for you!The second strategy I've used is to convince myself that I'm just conducting a tiny little experiment, just to see what happens. To do this, ask yourself to take a baby step but nothing more. Perhaps you hope to someday go to a pizza party with your friends, but everything about it terrifies you (the pizza! the chaos! people seeing me eat! food decisions! strangers! ack!). So, start really, really small, by just looking at the menu of a local pizza place and asking yourself what your favorite kind of pizza is. You don't have to go there. You don't have to order it. You don't have to eat it. You just have to take one small step toward these other things. If you can get through that first baby step, stop and observe the result of your experiment. Are you okay? Were you able to identify what kind of pizza you would like the most? Great! Now, the next step might be to go to the pizza place with no intention of eating there. Just walk by outside and look into a window. Still okay? Great. Next time you can go in, ask to see a menu (so you have something to say), and then turn around and leave.The next step might be to go there with a very close friend or family member, but eat ahead of time, so all you have to do is sit in the pizza place while the other person has a slice. Or maybe the next step would be to go in by yourself to eat a slice of pizza on your own. Or maybe you'll ask for a slice of pizza "to go" and then eat it at home. Either way, the point here is to take very small steps without any expectation of doing more than that one step at any time. Then you take the next one, and then the next, and eventually you'll have "tested" each step of the way. This may sound excruciatingly slow or drawn out, but if it works, who cares, right?You can do it!

Image found HERE.The experience of having—and recovering from—an eating disorder takes many forms, because many different kinds of people experience EDs. Many eating disorder sufferers experience crippling phobias and obsessive thoughts related to eating and body image. One phobia many people have heard of is having extreme fear of certain foods, or food groups. Another commonly known experience is one of obsessive counting, whether counting calories, carbs or minutes exercising.Some less well-known fears, however, have to do with the social aspects of eating, which add an additional layer to an individual's struggles managing food or exercise-related symptoms. Eating is a social experience in most cultures, including in American culture. We see advertisements depicting big family meals as a time when people connect with each other at the end of the day. One of Normal Rockwell's most famous pieces features Thanksgiving dinner in this way. The common dating phrase "dinner and a movie" similarly links food with social connection, and pretty much every high school movie depicts the school cafeteria as a modern day Roman Forum! Suffice it to say, most of us associate eating with spending time with friends and family.But eating socially can be a huge challenge for people who are suffering from or in recovery from eating disorders. Sometimes, this challenge is due to attempts to hide disordered eating habits from friends and family. Sometimes, those struggling eat in isolation not only to be secretive, but also to avoid scrutiny, critique or feeling freakish. It's also common for individuals with eating disorders to experience exaggerated feelings of being watched or judged while eating.Once a pattern of eating in isolation has become a habit, the prospect of eating socially, or even of eating alone but in a public place, can trigger major anxiety, sometimes leading to panic attacks. Not everyone experiences this, but it's more common than most people think.There are many well-researched approaches to overcoming fearful experiences. In extreme cases, such as when a person experiences panic attacks or if the social phobia begins to extend beyond just eating situations, it's almost always necessary to work with a therapist with special training on managing phobias. For cases that are less extreme but still distressing, here are some tips. First, when in recovery from an eating disorder, your first priority must be to take care of your body, even if this sometimes means neglecting social experiences. If your body isn't properly nourished and rested, your brain can't work effectively. If your brain isn't working effectively, your efforts on the psychological side of recovery will be even more difficult.So, if nourishing yourself properly means missing out on a slumber party or two, so what? However, this only makes sense if you are actually able to nourish yourself in less social contexts. And it can't go on forever. At some point, whether it takes days or weeks or months, it's important to rejoin the social world of eating.There are two strategies I've used when facing a fear. The first one is to deliberately—and in all seriousness—ask yourself, "realistically, what's the absolute worst thing that could happen? How would I survive that?" (Note the choice of the word "realistically." That means you should avoid imagining scenarios of an asteroid falling on the restaurant, okay?)Once you've answered this question to yourself, come up with a plan to survive it. Notice I did not say "come up with a plan to guarantee that this never happens!" Facing fears by avoiding them is what trapped in this situation in the first place. So let's try it: maybe your worst case scenario is that somebody comments on your eating in a way that is upsetting, whether it's a difficult relative or a nosy stranger. What would you do to survive it? Is there a phrase you could prepare in response, like "I know you think that commenting on my eating is helpful, but it isn't. Please give me some space." Afraid that could be too difficult or awkward? What if your plan was to burst into tears and run out of the room? That doesn't sound fun, but could you survive it? Think to yourself, "Well, if I burst into tears and run out of the room I will probably feel really embarrassed, but I will survive. I will not actually be in any real physical danger." When I describe this strategy, some of my friends find it incredibly useful and calming to be so specific and methodological in their planning, but others find that it increases their anxiety to imagine possible worst-case scenarios. Only use it if it works for you!The second strategy I've used is to convince myself that I'm just conducting a tiny little experiment, just to see what happens. To do this, ask yourself to take a baby step but nothing more. Perhaps you hope to someday go to a pizza party with your friends, but everything about it terrifies you (the pizza! the chaos! people seeing me eat! food decisions! strangers! ack!). So, start really, really small, by just looking at the menu of a local pizza place and asking yourself what your favorite kind of pizza is. You don't have to go there. You don't have to order it. You don't have to eat it. You just have to take one small step toward these other things. If you can get through that first baby step, stop and observe the result of your experiment. Are you okay? Were you able to identify what kind of pizza you would like the most? Great! Now, the next step might be to go to the pizza place with no intention of eating there. Just walk by outside and look into a window. Still okay? Great. Next time you can go in, ask to see a menu (so you have something to say), and then turn around and leave.The next step might be to go there with a very close friend or family member, but eat ahead of time, so all you have to do is sit in the pizza place while the other person has a slice. Or maybe the next step would be to go in by yourself to eat a slice of pizza on your own. Or maybe you'll ask for a slice of pizza "to go" and then eat it at home. Either way, the point here is to take very small steps without any expectation of doing more than that one step at any time. Then you take the next one, and then the next, and eventually you'll have "tested" each step of the way. This may sound excruciatingly slow or drawn out, but if it works, who cares, right?You can do it!

Image found HERE.The experience of having—and recovering from—an eating disorder takes many forms, because many different kinds of people experience EDs. Many eating disorder sufferers experience crippling phobias and obsessive thoughts related to eating and body image. One phobia many people have heard of is having extreme fear of certain foods, or food groups. Another commonly known experience is one of obsessive counting, whether counting calories, carbs or minutes exercising.Some less well-known fears, however, have to do with the social aspects of eating, which add an additional layer to an individual's struggles managing food or exercise-related symptoms. Eating is a social experience in most cultures, including in American culture. We see advertisements depicting big family meals as a time when people connect with each other at the end of the day. One of Normal Rockwell's most famous pieces features Thanksgiving dinner in this way. The common dating phrase "dinner and a movie" similarly links food with social connection, and pretty much every high school movie depicts the school cafeteria as a modern day Roman Forum! Suffice it to say, most of us associate eating with spending time with friends and family.But eating socially can be a huge challenge for people who are suffering from or in recovery from eating disorders. Sometimes, this challenge is due to attempts to hide disordered eating habits from friends and family. Sometimes, those struggling eat in isolation not only to be secretive, but also to avoid scrutiny, critique or feeling freakish. It's also common for individuals with eating disorders to experience exaggerated feelings of being watched or judged while eating.Once a pattern of eating in isolation has become a habit, the prospect of eating socially, or even of eating alone but in a public place, can trigger major anxiety, sometimes leading to panic attacks. Not everyone experiences this, but it's more common than most people think.There are many well-researched approaches to overcoming fearful experiences. In extreme cases, such as when a person experiences panic attacks or if the social phobia begins to extend beyond just eating situations, it's almost always necessary to work with a therapist with special training on managing phobias. For cases that are less extreme but still distressing, here are some tips. First, when in recovery from an eating disorder, your first priority must be to take care of your body, even if this sometimes means neglecting social experiences. If your body isn't properly nourished and rested, your brain can't work effectively. If your brain isn't working effectively, your efforts on the psychological side of recovery will be even more difficult.So, if nourishing yourself properly means missing out on a slumber party or two, so what? However, this only makes sense if you are actually able to nourish yourself in less social contexts. And it can't go on forever. At some point, whether it takes days or weeks or months, it's important to rejoin the social world of eating.There are two strategies I've used when facing a fear. The first one is to deliberately—and in all seriousness—ask yourself, "realistically, what's the absolute worst thing that could happen? How would I survive that?" (Note the choice of the word "realistically." That means you should avoid imagining scenarios of an asteroid falling on the restaurant, okay?)Once you've answered this question to yourself, come up with a plan to survive it. Notice I did not say "come up with a plan to guarantee that this never happens!" Facing fears by avoiding them is what trapped in this situation in the first place. So let's try it: maybe your worst case scenario is that somebody comments on your eating in a way that is upsetting, whether it's a difficult relative or a nosy stranger. What would you do to survive it? Is there a phrase you could prepare in response, like "I know you think that commenting on my eating is helpful, but it isn't. Please give me some space." Afraid that could be too difficult or awkward? What if your plan was to burst into tears and run out of the room? That doesn't sound fun, but could you survive it? Think to yourself, "Well, if I burst into tears and run out of the room I will probably feel really embarrassed, but I will survive. I will not actually be in any real physical danger." When I describe this strategy, some of my friends find it incredibly useful and calming to be so specific and methodological in their planning, but others find that it increases their anxiety to imagine possible worst-case scenarios. Only use it if it works for you!The second strategy I've used is to convince myself that I'm just conducting a tiny little experiment, just to see what happens. To do this, ask yourself to take a baby step but nothing more. Perhaps you hope to someday go to a pizza party with your friends, but everything about it terrifies you (the pizza! the chaos! people seeing me eat! food decisions! strangers! ack!). So, start really, really small, by just looking at the menu of a local pizza place and asking yourself what your favorite kind of pizza is. You don't have to go there. You don't have to order it. You don't have to eat it. You just have to take one small step toward these other things. If you can get through that first baby step, stop and observe the result of your experiment. Are you okay? Were you able to identify what kind of pizza you would like the most? Great! Now, the next step might be to go to the pizza place with no intention of eating there. Just walk by outside and look into a window. Still okay? Great. Next time you can go in, ask to see a menu (so you have something to say), and then turn around and leave.The next step might be to go there with a very close friend or family member, but eat ahead of time, so all you have to do is sit in the pizza place while the other person has a slice. Or maybe the next step would be to go in by yourself to eat a slice of pizza on your own. Or maybe you'll ask for a slice of pizza "to go" and then eat it at home. Either way, the point here is to take very small steps without any expectation of doing more than that one step at any time. Then you take the next one, and then the next, and eventually you'll have "tested" each step of the way. This may sound excruciatingly slow or drawn out, but if it works, who cares, right?You can do it!

Image found HERE.The experience of having—and recovering from—an eating disorder takes many forms, because many different kinds of people experience EDs. Many eating disorder sufferers experience crippling phobias and obsessive thoughts related to eating and body image. One phobia many people have heard of is having extreme fear of certain foods, or food groups. Another commonly known experience is one of obsessive counting, whether counting calories, carbs or minutes exercising.Some less well-known fears, however, have to do with the social aspects of eating, which add an additional layer to an individual's struggles managing food or exercise-related symptoms. Eating is a social experience in most cultures, including in American culture. We see advertisements depicting big family meals as a time when people connect with each other at the end of the day. One of Normal Rockwell's most famous pieces features Thanksgiving dinner in this way. The common dating phrase "dinner and a movie" similarly links food with social connection, and pretty much every high school movie depicts the school cafeteria as a modern day Roman Forum! Suffice it to say, most of us associate eating with spending time with friends and family.But eating socially can be a huge challenge for people who are suffering from or in recovery from eating disorders. Sometimes, this challenge is due to attempts to hide disordered eating habits from friends and family. Sometimes, those struggling eat in isolation not only to be secretive, but also to avoid scrutiny, critique or feeling freakish. It's also common for individuals with eating disorders to experience exaggerated feelings of being watched or judged while eating.Once a pattern of eating in isolation has become a habit, the prospect of eating socially, or even of eating alone but in a public place, can trigger major anxiety, sometimes leading to panic attacks. Not everyone experiences this, but it's more common than most people think.There are many well-researched approaches to overcoming fearful experiences. In extreme cases, such as when a person experiences panic attacks or if the social phobia begins to extend beyond just eating situations, it's almost always necessary to work with a therapist with special training on managing phobias. For cases that are less extreme but still distressing, here are some tips. First, when in recovery from an eating disorder, your first priority must be to take care of your body, even if this sometimes means neglecting social experiences. If your body isn't properly nourished and rested, your brain can't work effectively. If your brain isn't working effectively, your efforts on the psychological side of recovery will be even more difficult.So, if nourishing yourself properly means missing out on a slumber party or two, so what? However, this only makes sense if you are actually able to nourish yourself in less social contexts. And it can't go on forever. At some point, whether it takes days or weeks or months, it's important to rejoin the social world of eating.There are two strategies I've used when facing a fear. The first one is to deliberately—and in all seriousness—ask yourself, "realistically, what's the absolute worst thing that could happen? How would I survive that?" (Note the choice of the word "realistically." That means you should avoid imagining scenarios of an asteroid falling on the restaurant, okay?)Once you've answered this question to yourself, come up with a plan to survive it. Notice I did not say "come up with a plan to guarantee that this never happens!" Facing fears by avoiding them is what trapped in this situation in the first place. So let's try it: maybe your worst case scenario is that somebody comments on your eating in a way that is upsetting, whether it's a difficult relative or a nosy stranger. What would you do to survive it? Is there a phrase you could prepare in response, like "I know you think that commenting on my eating is helpful, but it isn't. Please give me some space." Afraid that could be too difficult or awkward? What if your plan was to burst into tears and run out of the room? That doesn't sound fun, but could you survive it? Think to yourself, "Well, if I burst into tears and run out of the room I will probably feel really embarrassed, but I will survive. I will not actually be in any real physical danger." When I describe this strategy, some of my friends find it incredibly useful and calming to be so specific and methodological in their planning, but others find that it increases their anxiety to imagine possible worst-case scenarios. Only use it if it works for you!The second strategy I've used is to convince myself that I'm just conducting a tiny little experiment, just to see what happens. To do this, ask yourself to take a baby step but nothing more. Perhaps you hope to someday go to a pizza party with your friends, but everything about it terrifies you (the pizza! the chaos! people seeing me eat! food decisions! strangers! ack!). So, start really, really small, by just looking at the menu of a local pizza place and asking yourself what your favorite kind of pizza is. You don't have to go there. You don't have to order it. You don't have to eat it. You just have to take one small step toward these other things. If you can get through that first baby step, stop and observe the result of your experiment. Are you okay? Were you able to identify what kind of pizza you would like the most? Great! Now, the next step might be to go to the pizza place with no intention of eating there. Just walk by outside and look into a window. Still okay? Great. Next time you can go in, ask to see a menu (so you have something to say), and then turn around and leave.The next step might be to go there with a very close friend or family member, but eat ahead of time, so all you have to do is sit in the pizza place while the other person has a slice. Or maybe the next step would be to go in by yourself to eat a slice of pizza on your own. Or maybe you'll ask for a slice of pizza "to go" and then eat it at home. Either way, the point here is to take very small steps without any expectation of doing more than that one step at any time. Then you take the next one, and then the next, and eventually you'll have "tested" each step of the way. This may sound excruciatingly slow or drawn out, but if it works, who cares, right?You can do it!Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on October 24, 2016 06:00

September 26, 2016

Dear KJ: My Mother is Urging Me to Lose Weight for My Wedding. Help!

Dear KJ: I’m planning a wedding and my mother keeps telling me to lose weight to look better in the photos. How can I confront her about this without starting a fight? (Posted first HERE)

Image originally posted HERE.

Image originally posted HERE.

Wow. I completely understand how you feel. In fact, the anxiety I felt about my body when I was planning my wedding was so intense that I ended up writing a book about it! I wasn't getting pressure from my mom to lose weight, but I was pressuring myself. You can read all about that in my book, or in this op-ed I wrote, but to answer your question I asked one of my sociology colleagues, Maddie Jo Evans, who is not only doing a research project on the wedding industry, but is also a wedding photographer on the side! Here's what Maddie had to say:

Image originally posted HERE.

Image originally posted HERE.Wow. I completely understand how you feel. In fact, the anxiety I felt about my body when I was planning my wedding was so intense that I ended up writing a book about it! I wasn't getting pressure from my mom to lose weight, but I was pressuring myself. You can read all about that in my book, or in this op-ed I wrote, but to answer your question I asked one of my sociology colleagues, Maddie Jo Evans, who is not only doing a research project on the wedding industry, but is also a wedding photographer on the side! Here's what Maddie had to say:

From what I have seen in my field work, in my interviews and as a wedding photographer, mothers and mother-in-laws seem to be the most likely to put pressure on their daughters/in-laws to lose weight. Many of the women I've spoken with have said that their mothers were the first to mention or "hint" that they ought to drop some weight for their wedding day. Most of them say that it is difficult for them to push back because their mothers are helping to pay for the wedding and the dress. Some brides even feel pressure to buy a dress in a smaller size than their current body.Many brides say that their mothers have always been their biggest critics and many have dealt with their moms making remarks about their bodies throughout their entire lives, but things become amplified by the wedding. Being exposed to messages from bridal media, mothers, family members and partners make the idea of losing weight for your wedding a normalized and expected thing. Even women who were satisfied with their bodies on any normal day worried that their current body would not be good enough for their wedding day. This pressure can push brides into unhealthy eating and workout patterns. My advice is to explain to your mother that you're is happy with the way that you look, and that you feel beautiful in your own skin. If you feel that you will be happy on your wedding day without losing any weight, then I hope you can respectfully tell your mother that and make it known that you aren't willing to change yourself for the expectations of others, even your mom. Our culture teaches us that the only way to be a beautiful bride is to be a thin bride, and this simply is NOT TRUE! As a wedding photographer I can promise you that it is not weight loss, but happiness and confidence that make for the most beautiful wedding photos. Have a wonderful time!Best,Maddie Jo EvansP.S. (from KJ) - Also, it might not hurt to remind your mother that all of this pressure for brides to lose weight is part of a huge wedding "industry" that makes gazillions of dollars by convincing brides AND their families that the only way to have a good-enough wedding is for everything to be perfect, from the dress to the decorations to the bodies of the people on display. This pressure is SO gendered. We assume that brides and their mothers are totally responsible for making sure everything is perfect, which is really sexist and stupid. But, given this, maybe your mom is feeling pressure from these cultural ideals, rather than from her own heart. She might even feel a sense of relief if you show her that your priorities are not about keeping up appearances, but about celebrating with your soon-to-be-spouse and family and friends. Assure her that she can help you have your dream wedding by worrying about what's best for you rather than striving for an impossible and expensive standard of perfection! - KJSaveSave

Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on September 26, 2016 06:00

September 5, 2016

Dear KJ: How I keep college classes from unraveling my recovery?

Dear KJ: How I keep college classes from unraveling my recovery?

You may have heard the phrase “knowledge is power.” Usually, this is a true statement, but not always. SELF-knowledge, I would argue, is almost always empowering, but school learnin’ can occasionally push you in the opposite direction. I should know—between kindergarten and finishing my PhD I’ve spent about 25 years (!) of my life taking classes. Out of those years, over half were shared with an eating disorder, in recovery or post-recovery. Here are a few things that have been challenging to me along the way, specifically in relation to recovery, and how you might be able to address them.Some classes can be triggering. Remember what I wrote above about SELF-knowledge being the most empowering? It’s self-knowledge that will help you avoid or at least disengage from classroom experiences (or entire courses!) that are triggering. While you’re still in active recovery, be wary of courses on topics that overlap with your eating disorder experiences. I’m not saying you can’t or shouldn’t ever take a course on, say, nutrition, but having an honest conversation with yourself (or your therapist) might reveal that some courses appeal to you precisely because they allow you to continue obsessing about food, exercise and body size stuff. I remember buying nutrition textbooks, thinking, “I’ll just replace my eating disorder with a 110% perfect ‘normal’ way of eating,” not realizing that in order for eating to be normal it cannot be anywhere near 110% perfect!But here’s the thing—it’s rarely the course topic itself that is inherently problematic, but the style in which it is taught. If you’re interested in taking a course or two with triggering potential, it might be a good idea to get your hands on a syllabus. Some professors will provide "trigger warnings" to draw attention to course material that might be triggering to students who have had traumatic experiences, but don't depend on this. Many instructors strongly prefer to not provide them. Ultimately it is your responsibility to know the difference between course material that is challenging (good!) and course material that is triggering (not so good!). If you have concerns, speak with the professor to ask her/him whether or not any of their course material could be difficult for a person in recovery from an eating disorder. Even without specific training in body-positive teaching styles, most instructors will have a sense for how to answer this question.Depending on the answer, you may opt to avoid the course, or you may become even more excited about it. You may also decide that most of the course sounds great, but that you’ll need to skip a day or two of class (I give you my permission!) if the lecture or readings seem triggering. Again, best to have a good conversation with yourself and/or your therapist.The second challenge that classes present to recovery is simply that going to school, whether part time or full time, adds stress to your life. You’ll be managing lectures, homework, deadlines, grading, as well as the social elements of school. Having some stress in your life is normal and usually healthy, but this is not the best time to overwhelm yourself. Start out with what you think is a realistic course load, but don’t hesitate to drop a class if you notice that you aren’t able to keep up with your classes and also take care of yourself. Don’t forget to have some fun, too!

You may have heard the phrase “knowledge is power.” Usually, this is a true statement, but not always. SELF-knowledge, I would argue, is almost always empowering, but school learnin’ can occasionally push you in the opposite direction. I should know—between kindergarten and finishing my PhD I’ve spent about 25 years (!) of my life taking classes. Out of those years, over half were shared with an eating disorder, in recovery or post-recovery. Here are a few things that have been challenging to me along the way, specifically in relation to recovery, and how you might be able to address them.Some classes can be triggering. Remember what I wrote above about SELF-knowledge being the most empowering? It’s self-knowledge that will help you avoid or at least disengage from classroom experiences (or entire courses!) that are triggering. While you’re still in active recovery, be wary of courses on topics that overlap with your eating disorder experiences. I’m not saying you can’t or shouldn’t ever take a course on, say, nutrition, but having an honest conversation with yourself (or your therapist) might reveal that some courses appeal to you precisely because they allow you to continue obsessing about food, exercise and body size stuff. I remember buying nutrition textbooks, thinking, “I’ll just replace my eating disorder with a 110% perfect ‘normal’ way of eating,” not realizing that in order for eating to be normal it cannot be anywhere near 110% perfect!But here’s the thing—it’s rarely the course topic itself that is inherently problematic, but the style in which it is taught. If you’re interested in taking a course or two with triggering potential, it might be a good idea to get your hands on a syllabus. Some professors will provide "trigger warnings" to draw attention to course material that might be triggering to students who have had traumatic experiences, but don't depend on this. Many instructors strongly prefer to not provide them. Ultimately it is your responsibility to know the difference between course material that is challenging (good!) and course material that is triggering (not so good!). If you have concerns, speak with the professor to ask her/him whether or not any of their course material could be difficult for a person in recovery from an eating disorder. Even without specific training in body-positive teaching styles, most instructors will have a sense for how to answer this question.Depending on the answer, you may opt to avoid the course, or you may become even more excited about it. You may also decide that most of the course sounds great, but that you’ll need to skip a day or two of class (I give you my permission!) if the lecture or readings seem triggering. Again, best to have a good conversation with yourself and/or your therapist.The second challenge that classes present to recovery is simply that going to school, whether part time or full time, adds stress to your life. You’ll be managing lectures, homework, deadlines, grading, as well as the social elements of school. Having some stress in your life is normal and usually healthy, but this is not the best time to overwhelm yourself. Start out with what you think is a realistic course load, but don’t hesitate to drop a class if you notice that you aren’t able to keep up with your classes and also take care of yourself. Don’t forget to have some fun, too!

You may have heard the phrase “knowledge is power.” Usually, this is a true statement, but not always. SELF-knowledge, I would argue, is almost always empowering, but school learnin’ can occasionally push you in the opposite direction. I should know—between kindergarten and finishing my PhD I’ve spent about 25 years (!) of my life taking classes. Out of those years, over half were shared with an eating disorder, in recovery or post-recovery. Here are a few things that have been challenging to me along the way, specifically in relation to recovery, and how you might be able to address them.Some classes can be triggering. Remember what I wrote above about SELF-knowledge being the most empowering? It’s self-knowledge that will help you avoid or at least disengage from classroom experiences (or entire courses!) that are triggering. While you’re still in active recovery, be wary of courses on topics that overlap with your eating disorder experiences. I’m not saying you can’t or shouldn’t ever take a course on, say, nutrition, but having an honest conversation with yourself (or your therapist) might reveal that some courses appeal to you precisely because they allow you to continue obsessing about food, exercise and body size stuff. I remember buying nutrition textbooks, thinking, “I’ll just replace my eating disorder with a 110% perfect ‘normal’ way of eating,” not realizing that in order for eating to be normal it cannot be anywhere near 110% perfect!But here’s the thing—it’s rarely the course topic itself that is inherently problematic, but the style in which it is taught. If you’re interested in taking a course or two with triggering potential, it might be a good idea to get your hands on a syllabus. Some professors will provide "trigger warnings" to draw attention to course material that might be triggering to students who have had traumatic experiences, but don't depend on this. Many instructors strongly prefer to not provide them. Ultimately it is your responsibility to know the difference between course material that is challenging (good!) and course material that is triggering (not so good!). If you have concerns, speak with the professor to ask her/him whether or not any of their course material could be difficult for a person in recovery from an eating disorder. Even without specific training in body-positive teaching styles, most instructors will have a sense for how to answer this question.Depending on the answer, you may opt to avoid the course, or you may become even more excited about it. You may also decide that most of the course sounds great, but that you’ll need to skip a day or two of class (I give you my permission!) if the lecture or readings seem triggering. Again, best to have a good conversation with yourself and/or your therapist.The second challenge that classes present to recovery is simply that going to school, whether part time or full time, adds stress to your life. You’ll be managing lectures, homework, deadlines, grading, as well as the social elements of school. Having some stress in your life is normal and usually healthy, but this is not the best time to overwhelm yourself. Start out with what you think is a realistic course load, but don’t hesitate to drop a class if you notice that you aren’t able to keep up with your classes and also take care of yourself. Don’t forget to have some fun, too!

You may have heard the phrase “knowledge is power.” Usually, this is a true statement, but not always. SELF-knowledge, I would argue, is almost always empowering, but school learnin’ can occasionally push you in the opposite direction. I should know—between kindergarten and finishing my PhD I’ve spent about 25 years (!) of my life taking classes. Out of those years, over half were shared with an eating disorder, in recovery or post-recovery. Here are a few things that have been challenging to me along the way, specifically in relation to recovery, and how you might be able to address them.Some classes can be triggering. Remember what I wrote above about SELF-knowledge being the most empowering? It’s self-knowledge that will help you avoid or at least disengage from classroom experiences (or entire courses!) that are triggering. While you’re still in active recovery, be wary of courses on topics that overlap with your eating disorder experiences. I’m not saying you can’t or shouldn’t ever take a course on, say, nutrition, but having an honest conversation with yourself (or your therapist) might reveal that some courses appeal to you precisely because they allow you to continue obsessing about food, exercise and body size stuff. I remember buying nutrition textbooks, thinking, “I’ll just replace my eating disorder with a 110% perfect ‘normal’ way of eating,” not realizing that in order for eating to be normal it cannot be anywhere near 110% perfect!But here’s the thing—it’s rarely the course topic itself that is inherently problematic, but the style in which it is taught. If you’re interested in taking a course or two with triggering potential, it might be a good idea to get your hands on a syllabus. Some professors will provide "trigger warnings" to draw attention to course material that might be triggering to students who have had traumatic experiences, but don't depend on this. Many instructors strongly prefer to not provide them. Ultimately it is your responsibility to know the difference between course material that is challenging (good!) and course material that is triggering (not so good!). If you have concerns, speak with the professor to ask her/him whether or not any of their course material could be difficult for a person in recovery from an eating disorder. Even without specific training in body-positive teaching styles, most instructors will have a sense for how to answer this question.Depending on the answer, you may opt to avoid the course, or you may become even more excited about it. You may also decide that most of the course sounds great, but that you’ll need to skip a day or two of class (I give you my permission!) if the lecture or readings seem triggering. Again, best to have a good conversation with yourself and/or your therapist.The second challenge that classes present to recovery is simply that going to school, whether part time or full time, adds stress to your life. You’ll be managing lectures, homework, deadlines, grading, as well as the social elements of school. Having some stress in your life is normal and usually healthy, but this is not the best time to overwhelm yourself. Start out with what you think is a realistic course load, but don’t hesitate to drop a class if you notice that you aren’t able to keep up with your classes and also take care of yourself. Don’t forget to have some fun, too! Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on September 05, 2016 17:16

August 1, 2016

Dear KJ: How Can I Be a Body-Positive Role Model for Young Girls

Dear KJ,

What is the best thing I can do as a 20-something woman who has recovered from eating disorders to help young girls establish good body image? (originally posted here)

What is the best thing I can do as a 20-something woman who has recovered from eating disorders to help young girls establish good body image? (originally posted here)

The best thing you can do to help young girls establish good body image is the same as what anyone else can do: be a role model for healthy body image and for having a healthy relationship with food. This means committing to talk about your body and other women's bodies in nonjudgmental ways, resisting fat talk, resisting diet talk and openly embracing and celebrating a wide variety of body shapes and sizes. Sometimes, this means faking it until you make it by resisting negative body talk and diet talk, even when you're struggling with negative body thoughts yourself. But, believe it or not, committing to being a role model for younger women can also empower you in your own health. Learning to view myself as a role model for other women—particularly for my female college students—has been one of my most powerful tools for staying healthy and appreciating myself. To me, being a role model has never meant being "perfect." We have plenty of “perfect” role models out there in our popular culture of fables, fairy tales and romantic comedies, telling young women and girls that success, happiness and love can only be theirs if they look like Barbie dolls and make it their life’s work to please others. Weird, nerdy girls don’t get the guy until they've had a makeover, which for some reason always involves ditching her glasses (What is it that they say? “Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses.”)! This is not what I want for my students and other young women. I want them to take their unique lives, unique bodies and unique minds and stride confidently along their own paths. I want them to find love and embrace it, rather than doubt it. I want them to revel in their quirks, and say PHOOEY! to people and media who tell them they need to look or act a certain way in order to be happy. I can't truly encourage my students to do this while being a slave to the same systems I'm critiquing. (And it's not like students don't notice when their teachers are trying to look like Barbie dolls!)

Because of this, I think that imperfect women who have fabulous lives make great role models. So, when I consciously try to be a role model, I relish in being as vibrantly imperfect and quirky —yet successful, loved and happy—as possible. I believe that being a role model in this way is good for my students and the other young women in my life, and I know that it's been good for me. Numerous times when I’ve been tempted to go on a crash diet—or to otherwise look perfect and act perfectly composed and put together—I’ve talked myself out of it simply by reminding myself of how badly I want to prove to my girls that quirky, chubby, bossy, outspoken, clumsy, weird girls can absolutely achieve professional success, wonderful friends and fabulous love.

What is the best thing I can do as a 20-something woman who has recovered from eating disorders to help young girls establish good body image? (originally posted here)

What is the best thing I can do as a 20-something woman who has recovered from eating disorders to help young girls establish good body image? (originally posted here)The best thing you can do to help young girls establish good body image is the same as what anyone else can do: be a role model for healthy body image and for having a healthy relationship with food. This means committing to talk about your body and other women's bodies in nonjudgmental ways, resisting fat talk, resisting diet talk and openly embracing and celebrating a wide variety of body shapes and sizes. Sometimes, this means faking it until you make it by resisting negative body talk and diet talk, even when you're struggling with negative body thoughts yourself. But, believe it or not, committing to being a role model for younger women can also empower you in your own health. Learning to view myself as a role model for other women—particularly for my female college students—has been one of my most powerful tools for staying healthy and appreciating myself. To me, being a role model has never meant being "perfect." We have plenty of “perfect” role models out there in our popular culture of fables, fairy tales and romantic comedies, telling young women and girls that success, happiness and love can only be theirs if they look like Barbie dolls and make it their life’s work to please others. Weird, nerdy girls don’t get the guy until they've had a makeover, which for some reason always involves ditching her glasses (What is it that they say? “Men seldom make passes at girls who wear glasses.”)! This is not what I want for my students and other young women. I want them to take their unique lives, unique bodies and unique minds and stride confidently along their own paths. I want them to find love and embrace it, rather than doubt it. I want them to revel in their quirks, and say PHOOEY! to people and media who tell them they need to look or act a certain way in order to be happy. I can't truly encourage my students to do this while being a slave to the same systems I'm critiquing. (And it's not like students don't notice when their teachers are trying to look like Barbie dolls!)

Because of this, I think that imperfect women who have fabulous lives make great role models. So, when I consciously try to be a role model, I relish in being as vibrantly imperfect and quirky —yet successful, loved and happy—as possible. I believe that being a role model in this way is good for my students and the other young women in my life, and I know that it's been good for me. Numerous times when I’ve been tempted to go on a crash diet—or to otherwise look perfect and act perfectly composed and put together—I’ve talked myself out of it simply by reminding myself of how badly I want to prove to my girls that quirky, chubby, bossy, outspoken, clumsy, weird girls can absolutely achieve professional success, wonderful friends and fabulous love.

Subscribe to Mirror, Mirror... OFF The Wall.

Published on August 01, 2016 10:38

February 29, 2016

Fix your Face! (repost from Gender & Society)

(originally posted HERE at the Gender & Society blog)

Last fall, the New York Times ran an op-ed piece (here) about beauty, or really, about ugliness. The Gender & Society blog Erynn Casanova and me, to write responses to the article and comment on the 2013 book that prompted the NYT commentary. Both of our responses are below. What a fabulously fun intellectual conversation!By Erynn Masi de CasanovaUgly. Some words sound like what they mean. We avoid calling people ugly in polite conversation, but are usually bold enough to whisper it behind their backs. Julia Baird’s recent op-ed in The New York Times raises the question of how children are socialized into beliefs about and reactions to a less-than-lovely appearance. As a case study, she chooses a children’s book based on the real-life experiences of its author, Robert Hoge, which is a memoir recounting his childhood with a large facial tumor and distorted limbs. His book is simply titled Ugly. Baird wonders how children come to learn about and take part in a system of “looksism,” and “why we talk about plainness, but not faces that would make a surgeon’s fingers itch.”Surgery came immediately to my mind on reading Baird’s column. Elective surgery to alter the human body’s appearance goes by many names. Plastic surgery emphasizes the malleability of the body and its parts. Aesthetic surgerymakes it sound as if we can turn our bodies into works of art. Cosmetic surgeryconjures makeup rather than sedation and scalpels. And while Baird acknowledges that surgeons might want to fix faces like Mr. Hoge’s, she doesn’t mention that the possibilities cosmetic surgery opens up also affect social judgements of appearance in everyday life.If we stick with the example of “distorted” facial features, but consider adults’ rather than children’s reactions, we can imagine people thinking, “Why doesn’t he fix it?” Surgeries exist that can help people in their quest for a “normal” appearance, which some research has shown is a more common goal for patients than achieving drop-dead gorgeous glamour . Eschewing elective surgery seems like a conscious choice to live “with flawed features in a world of facial inequality,” as Baird puts it in her op-ed.Here’s where the rise of what sociologist Victoria Pitts-Taylor calls “cosmetic wellness” comes in. In the United States and other wealthy countries, taking care of our health—and all the bodily practices that it involves—is now a requirement to be a moral person. Contemporary health morality pressures us all to monitor our health: this pressure and the blame it spawns are clearly visible in pop culture’s portrayals of obese people. We interpret an attractive appearance as evidence of physical and mental health. If looking good is health and being healthy is being a good person, then unattractiveness becomes an even bigger threat to social acceptance. Ugliness becomes as immoral and irresponsible as fatness or smoking cigarettes—also frowned on by the devotees of the new health morality. Good patient, good consumer, and good person are coterminous.But “facial inequality” doesn’t exist outside of other kinds of inequality. Our financial resources limit our ability to participate in cosmetic wellness and health morality. Sometimes the answer to why he doesn’t fix it is that he can’t afford to. Elective surgery is expensive. Yet middle-class and working-class people pay in installments, take a second job, or cross national borders to be able to afford it. If a normal appearance can be bought, then those who aren’t able to buy it can be shunned. We begin to contemplate a future in which the high price of compulsory cosmetic wellness means that only the poor will be ugly. There’s nothing attractive about that. Erynn Masi de Casanova is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Cincinnati. She is the author ofMaking Up the Difference: Women, Beauty, and Direct Selling in Ecuador, winner of the National Women’s Studies Association’s Sara A. Whaley Book Prize, and most recently, Buttoned Up: Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity. She is co-editor (with Afshan Jafar) of the books Bodies without Borders and Global Beauty, Local Bodies.Casanova and Jafar also co-edit the book series Palgrave Studies in Globalization and Embodiment. She is a member of the editorial board of Gender & Society.By Kjerstin Gruys (me!)In the November 2014 NYT article, “Being Dishonest About Ugliness,” writer Julie Baird cites Australian author Robert Hoge, who argues that adults need to stop telling children that “looks don’t matter.” After all, he says, “They know perfectly well they do.” Instead of telling kids they’re all beautiful, we should “tell them it’s O.K. to look different,” and that, when it comes to physical beauty, children should “know that it’s just one thing in life, one characteristic among others.” In other words, it’s important for children to know that one does not need to be beautiful in order to find success, love and happiness.Psychological research bears much of this out. Statistically speaking, beauty has only a negligible impact on overall happiness. For example, in one study, researchers found that, despite being highly-prized by respondents, physical attractiveness predicted only small variances in survey respondents’ reports of pleasant feelings, unpleasant feelings, and life satisfaction. In another study, participants were asked questions about their levels of happiness while, unbeknownst to them, their looks were being rated on a one-to-five scale by the research team (yes, this is kind of creepy, but let’s leave the methodological conversation for another day!). Those rated in the top 15% in terms of beauty were roughly 10% happier than those in the bottom 10%. Now, a 10% increase in happiness may seem pretty meaningful (I’d take it!), but be careful to remember that this means that the most stunningly beautiful people – the breathtaking outliers – are only 10% happier than the most profoundly unattractive.“I’m happy to concede the point,” Hoge says, “that some people look more aesthetically pleasing than others. Let’s grant that so we can move to the important point – so what?”People often state that, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” but when the seemingly subjective concept – and social consequences – of “ugliness” maps again and again onto the bodies of poorer, fatter, and aging women of color, it’s time to acknowledge a broader structural problem. Yes, it’s important to help children develop healthy self-esteem and body image, but without addressing the power relations that drive our beauty standards, these efforts treat the symptoms rather than curing the disease.Dr. Kjerstin Gruys is a Thinking Matters Fellow at Stanford University and a Postdoctoral Scholar (by courtesy) at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research, also at Stanford. Her research broadly explores the relationship between physical appearance and social inequality, with a particular focus on gender as it intersects with race/ethnicity, class, sexuality, and age. She is currently developing a book manuscript, tentatively titled: True to Size?: A Social History of Clothing Size Standards in the U.S. Fashion Industry.

Last fall, the New York Times ran an op-ed piece (here) about beauty, or really, about ugliness. The Gender & Society blog Erynn Casanova and me, to write responses to the article and comment on the 2013 book that prompted the NYT commentary. Both of our responses are below. What a fabulously fun intellectual conversation!By Erynn Masi de CasanovaUgly. Some words sound like what they mean. We avoid calling people ugly in polite conversation, but are usually bold enough to whisper it behind their backs. Julia Baird’s recent op-ed in The New York Times raises the question of how children are socialized into beliefs about and reactions to a less-than-lovely appearance. As a case study, she chooses a children’s book based on the real-life experiences of its author, Robert Hoge, which is a memoir recounting his childhood with a large facial tumor and distorted limbs. His book is simply titled Ugly. Baird wonders how children come to learn about and take part in a system of “looksism,” and “why we talk about plainness, but not faces that would make a surgeon’s fingers itch.”Surgery came immediately to my mind on reading Baird’s column. Elective surgery to alter the human body’s appearance goes by many names. Plastic surgery emphasizes the malleability of the body and its parts. Aesthetic surgerymakes it sound as if we can turn our bodies into works of art. Cosmetic surgeryconjures makeup rather than sedation and scalpels. And while Baird acknowledges that surgeons might want to fix faces like Mr. Hoge’s, she doesn’t mention that the possibilities cosmetic surgery opens up also affect social judgements of appearance in everyday life.If we stick with the example of “distorted” facial features, but consider adults’ rather than children’s reactions, we can imagine people thinking, “Why doesn’t he fix it?” Surgeries exist that can help people in their quest for a “normal” appearance, which some research has shown is a more common goal for patients than achieving drop-dead gorgeous glamour . Eschewing elective surgery seems like a conscious choice to live “with flawed features in a world of facial inequality,” as Baird puts it in her op-ed.Here’s where the rise of what sociologist Victoria Pitts-Taylor calls “cosmetic wellness” comes in. In the United States and other wealthy countries, taking care of our health—and all the bodily practices that it involves—is now a requirement to be a moral person. Contemporary health morality pressures us all to monitor our health: this pressure and the blame it spawns are clearly visible in pop culture’s portrayals of obese people. We interpret an attractive appearance as evidence of physical and mental health. If looking good is health and being healthy is being a good person, then unattractiveness becomes an even bigger threat to social acceptance. Ugliness becomes as immoral and irresponsible as fatness or smoking cigarettes—also frowned on by the devotees of the new health morality. Good patient, good consumer, and good person are coterminous.But “facial inequality” doesn’t exist outside of other kinds of inequality. Our financial resources limit our ability to participate in cosmetic wellness and health morality. Sometimes the answer to why he doesn’t fix it is that he can’t afford to. Elective surgery is expensive. Yet middle-class and working-class people pay in installments, take a second job, or cross national borders to be able to afford it. If a normal appearance can be bought, then those who aren’t able to buy it can be shunned. We begin to contemplate a future in which the high price of compulsory cosmetic wellness means that only the poor will be ugly. There’s nothing attractive about that. Erynn Masi de Casanova is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Cincinnati. She is the author ofMaking Up the Difference: Women, Beauty, and Direct Selling in Ecuador, winner of the National Women’s Studies Association’s Sara A. Whaley Book Prize, and most recently, Buttoned Up: Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity. She is co-editor (with Afshan Jafar) of the books Bodies without Borders and Global Beauty, Local Bodies.Casanova and Jafar also co-edit the book series Palgrave Studies in Globalization and Embodiment. She is a member of the editorial board of Gender & Society.By Kjerstin Gruys (me!)In the November 2014 NYT article, “Being Dishonest About Ugliness,” writer Julie Baird cites Australian author Robert Hoge, who argues that adults need to stop telling children that “looks don’t matter.” After all, he says, “They know perfectly well they do.” Instead of telling kids they’re all beautiful, we should “tell them it’s O.K. to look different,” and that, when it comes to physical beauty, children should “know that it’s just one thing in life, one characteristic among others.” In other words, it’s important for children to know that one does not need to be beautiful in order to find success, love and happiness.Psychological research bears much of this out. Statistically speaking, beauty has only a negligible impact on overall happiness. For example, in one study, researchers found that, despite being highly-prized by respondents, physical attractiveness predicted only small variances in survey respondents’ reports of pleasant feelings, unpleasant feelings, and life satisfaction. In another study, participants were asked questions about their levels of happiness while, unbeknownst to them, their looks were being rated on a one-to-five scale by the research team (yes, this is kind of creepy, but let’s leave the methodological conversation for another day!). Those rated in the top 15% in terms of beauty were roughly 10% happier than those in the bottom 10%. Now, a 10% increase in happiness may seem pretty meaningful (I’d take it!), but be careful to remember that this means that the most stunningly beautiful people – the breathtaking outliers – are only 10% happier than the most profoundly unattractive.“I’m happy to concede the point,” Hoge says, “that some people look more aesthetically pleasing than others. Let’s grant that so we can move to the important point – so what?”People often state that, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” but when the seemingly subjective concept – and social consequences – of “ugliness” maps again and again onto the bodies of poorer, fatter, and aging women of color, it’s time to acknowledge a broader structural problem. Yes, it’s important to help children develop healthy self-esteem and body image, but without addressing the power relations that drive our beauty standards, these efforts treat the symptoms rather than curing the disease.Dr. Kjerstin Gruys is a Thinking Matters Fellow at Stanford University and a Postdoctoral Scholar (by courtesy) at the Clayman Institute for Gender Research, also at Stanford. Her research broadly explores the relationship between physical appearance and social inequality, with a particular focus on gender as it intersects with race/ethnicity, class, sexuality, and age. She is currently developing a book manuscript, tentatively titled: True to Size?: A Social History of Clothing Size Standards in the U.S. Fashion Industry.