David Price's Blog

January 7, 2018

Do Tory Chumps Trump Trump?

Not since the publication of the first Harry Potter novel has there been a response to a book (yes, a book!) as we’ve witnessed with the publication of ‘Fire and Fury’, by Michael Wolff. Its anecdotes and rumours will give satirists abundant material with which to poke the hapless leader of the free world. But, while we laugh along with Stephen Colbert and Jimmy Kimmel, we in the UK should remember two things: 1. Without Brexit, we would probably not have seen The Donald in the White House; 2. Our own administration has been behaving in a remarkably Trumpian fashion since last year’s general election. Since education is my thing, I’ve chosen to focus upon that, but I’m confident that commentators who were interested in say, health or transport, could offer a similar analogy.

So, here are four ways (at least) that the Conservative education strategy Is aping White House rules:

Keep telling lies, ignore evidence to the contrary. Schools minister Nick Gibb has consistently denied that recruitment – and retention – of teachers in schools in England is an issue. His manipulation of statistics looks like Sean Spicer has been doing the calculations. The reality, according to the TES, is that applications to teacher training programmes this year are down by a whopping 33%, and record numbers of teachers are leaving the profession. Analysts say that low-pay, excessive workloads, rock-bottom morale and increasing accountability all affect the numbers of people applying to teach, and the number of teachers still in the classroom after 5 years. It’s a crisis – but the government remains in denial. The latest novel tactic? Supporting Now Teach, the charity that seeks to talk ‘professionals’ out of retirement and into teaching. I know you might be thinking that teaching is a profession too, but apparently not. And, in the two years since being founded, Now Teach has had 50 graduates! Five-O! If this sounds familiar, you may recall Troops to Teachers, a scheme to fast-track military veterans into the classroom. Set up in 2016 with a £4.3m grant and an initial target of 2,000 applicants, the scheme graduated 28 teachers in 2016 (that’s only £153,571 a pop). So, 78 across both schemes more than compensates for the 34,910 teachers that left the profession in 2016 for reasons other than retirement. Doesn’t it?

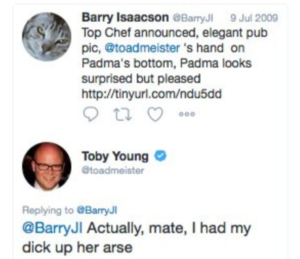

Value loyalty above experience. The government has, like Trump, preferred to surround itself with advisers and ‘tsars’ that are wholly unqualified to offer advice and tsaring, but are handsomely rewarded – either through promotions or substantial grants – for a particular form of ‘aggressive loyalty’. Government loyalist and all-round good-egg, Toby Young, (already Director of the New Schools Network) was last week chosen to be the Higher Education Student Tsar. Announcing his new job, the Department for Education falsely claimed that Young had held teaching posts at Harvard and Cambridge (he hadn’t, but see rule #1),It is as inept a decision as the appointment of Anthony Scaramucci as White House Communications Director – and likely to last about as long.

Character is for suckers. The most popular Secretary of State for Education in years, Justine Greening, is expected to lose her job in the Prime Minister’s cabinet reshuffle tomorrow. Meanwhile, self-confessed porn-addict Toby Young, universally criticised for his disgusting, misogynist Tweets over many years, is championed by Michael Gove and part-time Foreign Secretary/full-time BoBo the Clown stand-in, Boris Johnson. Johnson said that Young was the ‘ideal’ candidate, since he’d bring a ‘caustic wit’ to the job. (Apologies to anyone upset by the language used, but I thought I should include one of the 50,000 tweets Young has sought to furiously delete in the past few days, as an example of this caustic wit). Now, Greening is apparently taking the rap for the Tories failure to realise that education was seen by voters as a key issue at the last election (even though she wasn’t in post at the time). Young, meanwhile, blames the whole furore on the fact that he’s a Tory supporter, and not a believer in eugenics, or his fixation with women’s bodily parts. Theresa May has criticised Young, saying “I’m not at all impressed…if he continues to use that tone, he will no longer be in public office”. A Principal Skinner final warning from Mrs May then, but Mr Young, has (for the moment) mysteriously survived. Greening, however, is considered by May to be ‘patronising’ so she obviously has to go…..

Character is for suckers. The most popular Secretary of State for Education in years, Justine Greening, is expected to lose her job in the Prime Minister’s cabinet reshuffle tomorrow. Meanwhile, self-confessed porn-addict Toby Young, universally criticised for his disgusting, misogynist Tweets over many years, is championed by Michael Gove and part-time Foreign Secretary/full-time BoBo the Clown stand-in, Boris Johnson. Johnson said that Young was the ‘ideal’ candidate, since he’d bring a ‘caustic wit’ to the job. (Apologies to anyone upset by the language used, but I thought I should include one of the 50,000 tweets Young has sought to furiously delete in the past few days, as an example of this caustic wit). Now, Greening is apparently taking the rap for the Tories failure to realise that education was seen by voters as a key issue at the last election (even though she wasn’t in post at the time). Young, meanwhile, blames the whole furore on the fact that he’s a Tory supporter, and not a believer in eugenics, or his fixation with women’s bodily parts. Theresa May has criticised Young, saying “I’m not at all impressed…if he continues to use that tone, he will no longer be in public office”. A Principal Skinner final warning from Mrs May then, but Mr Young, has (for the moment) mysteriously survived. Greening, however, is considered by May to be ‘patronising’ so she obviously has to go…..Believe (or Tweet) six impossible things before breakfast. Trump maintains that he’s passed more legislation in his first year than any previous incumbent (fact-check: the opposite is actually the case) He has redefined contradictory policy-making – easy to do when you promulgate ‘alternative facts’, and your two closest advisers – Jared and Ivanka – admit to being Democrats. But the UK government are giving him a close run for his Russian money……In what may prove to be her final policy idea, Justine Greening launched the ‘Unlocking Talent, Fulfilling Potential’ plan in December 2017. The plan had four laudable ambitions: Close the language/literacy gap; Close the attainment gap; Offer real choice at post-16; Raise career aspirations. During the same month, the government saw the mass resignation of its Social Mobility Commission and its prominent Chair, Alan Milburn. Adopting Trumpian spin tactics, the government said he was going to be ‘stepped down’ anyway. Since almost losing the last election, the government has cut funding to schools, further and adult education. Child poverty rates are now 30%. And the attainment gap is widening: recently released data shows the impact of successive austerity cuts – the gap in numeracy, literacy and writing has grown ever wider between well-off students and those receiving free school meals, and better-off students are now twice as likely to be offered a university place than their poorer counterparts. Just as Trump’s recent massive tax-cut for the super-wealthy is his fulfillment of his pledge to remember the forgotten men and women of middle America, so the widening educational gap makes a sham of Theresa May’s incoming pledge to fight ‘burning injustice’ and ‘make Britain a country that works not for a privileged few, but for every one of us.’

The Prime Minister this morning repeated her insistence that Donald Trump would pay a visit to the UK in 2018. I’ll be joining the many UK citizens who will want to give him a welcome he will never forget. But amid the inevitable cacophony, we’d do well to remember that the playbook that got him into power, now appears to be required reading for a government and a Prime Minister desperate to cling to what little power they now retain. Welcome to the moral wasteland of British governance.

November 4, 2017

Enough Already With “Trad vs Prog”!

The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

The past few days have seen the opposite (if not equal) reaction to the recent emergence of the #EducationForward campaign. With scant regard for factual accuracy, various bloggers and tweeters (since they crave attention I’ll anonymise them for now) have attempted to summarise the Education Forward book, without the tiresome task of actually reading it. One, describing #EducationForward as ‘Education Backward’ (witty), linked EF to Class Action, the recently created magazine ‘by teachers for teachers’ (wrong). Others questioned how EF is funded (it isn’t). But the biggest (though I suspect knowing) misconception has been to cast Education Forward as promulgating ‘the vision of progressive education”.

If these bloggers had actually bothered to read the book, or watched Sir Ken Robinson’s opening to the recent conference, they would have seen repeated criticisms of the polarisation of education into Traditionalists and Progressives. So, only someone trying to pick a fight would deliberately cast the movement as one of the poles it is consciously avoiding. Education Forward’s objective is simply to change the conversation away from the same tired polarities (direct instruction vs discovery learning, academies vs comprehensives, etc) toward a much-needed discussion as to what kind of education system will be needed to enable young people to thrive in the future.

The people who attended the conference were talking about the need to adopt any teaching strategies that will help kids become more literate and numerate, globally aware, compassionate and curious, and equipped with the non-cognitive ‘soft’ skills that this week’s Education Policy Institute report argued are being neglected in the UK. One of the headteachers who spoke at the event was Mark Moorhouse, Headteacher at Matthew Moss High School in Rochdale. Mark talked about the school’s D6 initiative – recently praised by the government in its 2017 Parliamentary Review. I first observed D6, shortly after its introduction in 2014, and blogged about it here. I’ve just come back from a further visit, and it’s great to see that this non-ideological experiment now has clear evidence of its effectiveness.

D6 operates on a Saturday morning and is a voluntary peer-to-peer learning experiment. Teachers are in attendance, but not in classrooms – they make tea for students and catch up on their marking. There are learning ‘coaches’ – students from the local sixth-form college, who are there to support learners – though some students prefer to work on their own. The content being studied is entirely determined by each group of around 3-6 students, so it’s impossible for the coaches to prepare lectures or worksheets in advance. Today was a relatively quiet day – just over 100 students turned up, largely because a new group of coaches are being recruited. Despite that, two floors of the school were filled with students, deeply engaged, and in charge of, their learning. With so much freedom one might expect to see students kicking a football around or playing video games. Almost all of the students I saw today were grappling with maths, chemistry or science problems. The school serves a large Asian community, and Rochdale is an area of high deprivation. I saw one group of white working-class boys (the so-called ‘hard to reach’) jubilant that they’d finally cracked percentages and overheard another say “I think I’m getting the hang of maths now” – the level of student agency was palpable.

But, here’s the thing: the actual pedagogy being deployed was often classic note-taking, demonstration and explanation stuff. On Monday, many of the Year 7s will be doing projects, some of the Year 8s will be getting a history lecture, while some of the Year 11s may be doing test prep – and there is no conflict. Only in the confrontational minds of some binary edu-tweeters is the question ‘which side are you on?’ even worth considering: for these kids, it’s all just learning. But Matthew Moss High School is future-facing, in so far as it passionately believes that a love of learning will be vital to their students’ prospects, because the future demands that we will all have to learn, unlearn, and re-learn throughout our lives. So, student agency over their learning is paramount.

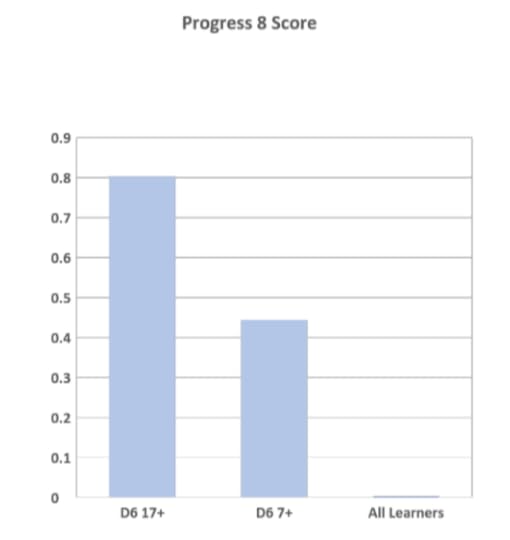

There are plenty of teachers that dismiss experiments like D6, arguing that research (they always seem to wheel out a single cognitive load study) ‘proves’ that novice learners need fully guided instruction and that ‘students are not good at making choices that optimise their learning’. Well, the students at D6 would beg to differ. Here’s the comparative test scores from last year’s D6 cohort who had attended 7 sessions, or more than 17 sessions, last year (overseas readers, please don’t ask me to explain how progress 8 scores work in England!):

D6 students Progress 8 Scores 2017 (0=National Average

There is also a minority belief that anything other than direct explicit instruction, delivered by an expert to novice, will disproportionately penalise students from low-income backgrounds. Matthew Moss have analysed the impact of D6 upon students attracting additional ‘pupil premium’ funding (those in receipt of free lunches). Here, the figures are particularly striking:

D6 Pupil Premium Progress 8 scores (0=National Average)

So, the introduction of peer-to-peer learning is having a remarkable impact upon test scores, learner confidence, and learner agency – especially among students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Education Forward wants parents, business leaders and educators to know that there are other models of instruction – neither ‘traditional’ nor ‘progressive’ but a combination of the two (if indeed one can categorise pedagogies as lazily as that) – that don’t present either/or scenarios. They can deliver good test scores and equip learners with the self-sustaining dispositions they’ll need throughout their lives. (It seems to be only in the UK that we have this obsession with these sterile arguments – the rest of the world’s educators must think we’re still in the 20th century.)

I’d urge educators to visit Matthew Moss High School to see D6 in action.

I’d urge everyone not to be drawn into pointless polarising debates on pedagogy, but instead to ask ‘how do we need to change our approach to education, in light of the enormous, disruptive changes that we’re facing?’

And I’d urge you to look at Education Forward’s 10 goals of future-focused education and, if you agree, show your support.

October 7, 2017

Postcard From The Future #3: New Roads, Urban Discovery Academy and Ideate High Academy

Mark Vickers-Willis , Dean of Middle School Students Welcomes our group

Days 4 & 5 of our study tour of future-focused schools took in three very different schools (for details of previous schools visited, see the last blog post).

Our first stop was New Roads School, a K-12 school, in Santa Monica. As the inspirational Principal Luthern Williams explained, New Roads is unique: an independent school entirely committed to social equity. In practice, this means that parents who can afford their fees know that 50% of those fees enable kids from under-privileged areas of Los Angeles to attend. You might think with such a disparity of backgrounds there’d be two distinct sets of students. In reality, it’s impossible to spot which students are on scholarships and which aren’t.

The four ‘pillars’ of New Roads – Social Justice, Environmental Stewardship, Diversity and Academic Excellence – are evident in every conversation, every piece of student work. Being located in Santa Monica they are, as Luthern put it, ‘surrounded by companies that are shaping the modern world’: new media, robotics, games developers and software developers abound, and New Roads makes full use of them.

When you forgo half of your income to ensure you achieve social, ethnic and racial diversity, then it’s not surprising to see that New Roads classrooms are, well, basic. But that doesn’t matter, because our group were consistent with other visitors to New Roads in being moved to tears by what Luthern describes as unashamed idealism. It’s hard to accurately dissect how this school works – the pedagogy that we saw wasn’t anything ground-breaking, but their students are astonishing. Their teachers described them variously as “diversity natives” and “global bridge-builders”, powerful advocates of a private school with a public purpose.

Students at New Roads

The highlight of our visit was a discussion with student ambassadors in the Steven Spielberg theatre (yes, he sent his kids there). They clearly demonstrated – not for the first time on our tour – that if you give students voice and choice, they will reward freedom with great responsibility. Students are taught, largely, by stage not age, and at high school are offered over sixty electives. In many schools such options might lead to a kind of paralysis of choice, but these students utilise this open curriculum to to allow them to find themselves (in the practical sense). One student praised the curriculum, saying “Here, I can be whoever I want to be” (at this moment that looks likely to be a forensic scientist). Another reflected on the personal responsibility that comes with a student-driven curriculum, saying “ If you’re open about where you’re struggling, or where you’re having difficulties, then help is available, but it’s your job to make the move”.

Luthern Williams shared research that shows that diversity isn’t just good for student’s empathy and compassion – it improves cognition too. This is a school where students are valued as equal members of a learning community, their weekly ‘Town Hall’ meetings often identify social and political issues that students feel strongly about – and then they plan action. So, the day before we arrived, the high school students marched in the streets surrounding the school in support of the US ‘dreamers’. Some students, however, felt uncomfortable, and their right not to take part was supported by their teachers. In a class that I witnessed, students were discussing possible links between violence and video games. Some schools might not want students to be discussing current political issues, but New Roads are explicit in their belief that schools have a key role to play in pursuit of the US founding father’s dream of ‘a more perfect union’. Unashamedly idealistic, New Roads is a brilliant example of how academic excellence can be driven by diversity and that perhaps the key purpose of a school is, to paraphrase Luthern Williams, ‘to give students the tools to make sense of the world on their terms, not ours’. I wish every dispirited teacher who believes that teachers make decisions about students’ learning because ‘they don’t know what they don’t know’ could spend a week in New Roads School.

The following day our group visited two sister schools in the urban heart of San Diego. Set up as a single ‘charter’ entity, the two schools (Urban Discovery Academy at K-8 and Ideate High Academy) represent the application of a start-up culture to the persistent problem of public schooling in the United States. Chris Wakefield, the principal of Ideate, showed us alarming statistics on the disparity of wealth in a city like San Diego. Since their schools only get paid on the days that students attend, the lower attendance rates invariably seen in inner-city schools mean that such schools have progressively been starved of money, and have become ever more socially unequal. In an attempt the halt this decline, charter schools are invited to bring more innovation into public education.

New Roads encourage students to question everything

Whatever one thinks of charters (in the UK, their equivalent is academies), they certainly don’t get any favours – there are good and bad examples to be found, but the bad ones don’t last long, with charter renewal coming along every five years. As the name suggests, Ideate High Academy have Design Thinking at the heart of their curriculum and early results (they’re only in their second year) are showing that student’s academic results are promising. However, they have another two years before their building is ready and the temporary premises they’re currently using are challenging to say the least – a recent outbreak of hepatitis A among the homeless community that inhabit the streets surrounding Ideate meant that hand sanitisers were everywhere. It doesn’t take more than a few minutes to see the scale of the challenge facing Chris. However, he only has to see the progress that his sister school, Urban Discovery Academy, has made to have cause for optimism.

Urban Discovery have come through the growing pains of a start-up, have a brand new building, and a waiting-list of students to confirm that they’re doing something right. The building itself is one of the most colourful I’ve seen, and the students seemed delighted with their new home. The ‘content rich’ dominance in recent years in the US definitely seems to have shifted in many urban charter schools and at UDA the curriculum is part STEAM, part project-based – in many ways a restoration of the liberal arts tradition that served US tertiary education so well. As any tech entrepreneur will tell you, starting-up is the hardest part of any project. New Roads School was also a start-up twenty years ago, and they’re now in a position at the forefront of change. We need more private schools with a public purpose. We also need people like Chris Wakefield with vision, boundless energy, and a determination to get over the challenges of start-up, to show that future-focused schools can meet the need for innovation and social purpose in our schools.

Urban Discovery have come through the growing pains of a start-up, have a brand new building, and a waiting-list of students to confirm that they’re doing something right. The building itself is one of the most colourful I’ve seen, and the students seemed delighted with their new home. The ‘content rich’ dominance in recent years in the US definitely seems to have shifted in many urban charter schools and at UDA the curriculum is part STEAM, part project-based – in many ways a restoration of the liberal arts tradition that served US tertiary education so well. As any tech entrepreneur will tell you, starting-up is the hardest part of any project. New Roads School was also a start-up twenty years ago, and they’re now in a position at the forefront of change. We need more private schools with a public purpose. We also need people like Chris Wakefield with vision, boundless energy, and a determination to get over the challenges of start-up, to show that future-focused schools can meet the need for innovation and social purpose in our schools.

September 30, 2017

Postcard From The Future Part Two

Is it a school or a great coffee house?

For the past three days, I’ve been taking a group of school leaders and teachers around some of the most innovative schools in the United States. We curated the visit to concentrate upon Silicon Valley, primarily because the startup culture and spirit of enterprise that has made this region boom, has impacted upon the re-design of education – so long as you know where to look. It’s also a place where the jobs of the future are being created in the knowledge economy.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, this spirit of innovation is found more commonly in independent schools. I wish that were not the case, but public schools here face many of the same constraints that curtail risk-taking in public schools everywhere. Later in the study tour, we’ll be looking at charter schools – where there is greater accountability than in the private sector.

Monte Vista Christian School Sports ground with a view…

The three schools we’ve visited – Monte Vista Christian School, near Watsonville (about an hour west of San Jose), Nueva School, San Mateo (near Palo Alto) and Alt School in San Francisco – have shown extraordinary generosity with the time and a genuine interest in what our international group of educators thought about their respective missions. As a result, the learning has already been immense.

Rather than give a school-by-school breakdown, it makes more sense to look for commonalities and trends. Here’s what has struck me so far:

Use of space: all three schools get the idea that kids can only learn well if they are comfortable – physically, emotionally and spiritually. Monte Vista is set in spectacular countryside. Despite its proximity to Silicon Valley, this is farming country, between the mountains and the sea. But Monte Vista is also in the throes of turning what were very traditional classrooms into spaces that feel more like family living rooms. Similarly, Nueva’s elementary and middle schools are set in beautiful grounds, with accommodation that’s a mix of the old and the

3rd Graders at Nueva discuss Culture – yes, 3rd graders…….

new. This has clearly had a profound effect on both Monte Vista and Nueva. Both have been around in excess of 50 years, and recognise their tradition and founding visions, but they’re not enslaved to them. Both were radical innovations in their creation, and they’re determined to keep innovating.

Ownership of learning : all three schools believe that students need to own their learning for it to prepare them for a lifetime of learning. At Nueva’s Upper School, half of the senior student’s schedule is made up of electives. And the choice is truly impressive: Social Justice, Experimental Biology, Drug Design, Machine Learning, Modern Film Making, Cultures of Postmodernism, Neuroscience and many more. Nueva’s Upper School felt more like a university than a school, and some students can gain university credit – not least because some of the student research work is at least undergraduate standard. Some students have been working on CRISPR gene editing, while others are carrying out original research into the P53 tumour suppressor protein. Nueva is a selective school, but the bar isn’t set at prohibitively high levels, and their students are doing really important research work, way in advance of standard common core standards.

Our educators meet in Monte Vista’s ‘library’

Alt-School essentially exists to shift learning from being teacher-centric to learner-centric. Founded by Max Ventilla – former senior product manager and head of personalisation at Google – it is a stunning example of the startup entrepreneurial culture of Silicon Valley, both in its ambition and its seriousness. Alt-School have 7 lab schools that work closely with over 50 tech engineers, all committed to truly personalising the student experience. It’s a ‘for-profit’ that is determined to have social impact in making learning competency-based, owned by students and embedded in a network of supportive relationships with parents and community. We saw the first beta version of the hugely impressive software platform that will be launched next year. It provides a 360 approach to a student’s learning: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment. As you’d expect from a former Googler, every is open, so parents are critically involved. But it is designed to enable the student to work out what they need to know, and how to find it, using the ‘playlist’ concept. Max is the brains behind the Google sidebar recommendations/ads tailored specifically to your previous interactions, so you can expect a learning management platform that is far more sophisticated than anything we’ve seen before, and one which will take full advantage of the network effect. When large numbers of students are using this platform (and Alt-School is soon to make its system widely available to schools in the public sector) we will have the most powerful dataset of how students learn, but also what pedagogies should be used in a range of contexts and conditions. It will make current ‘what works’ methodologies look primitive in comparison.

Making time and space for innovation: all three schools firm

ly believe in modelling the collaboration we look to see in student work, through adult learning. Monte Vista have a new principal, Mitch Salerno, who is building a real community of adult learners. So, our visit was seen less as a ‘show-and-tell’ and more of a great opportunity to learn from the Romanian, Indian, Australian and British educators in our group. Equally, we visited Nueva a couple of weeks before their conference around innovation in learning – run largely by parents. While we were visiting Nueva, Scott Swaaley was taking parents around their i-lab spaces – these are extraordinary places (it diminishes them to describe them as merely ‘makerspaces’) originally created by David Kelley of Ideo. So, design thinking infuses throughout their practice, fuelled by their close association with Stanford’s ‘d-school’ lab.

In order to stay fresh, Nueva hire in subject specialists as well as accredited teachers. They believe that, if you’re future-focussed, it’s easier to train teaching knowledge than subject expertise. So, they have a sophisticated internal training programme, and make the time for it through reduced teaching loads.

Similarly, Alt-School is a living laboratory to study teaching and learning behaviours and impacts. Every interaction between teacher and student is videoed and analysed. It then ad

Nueva’s beautiful campus – elementary school or university?

ds to the growing database they have that informs continuous conscious performance improvement.

These are just three ways that innovative schools in California are looking to the future needs of students and in building systems at scale. I could talk about their attitudes towards building self-sufficiency, compassion, social purpose in their students, but that can wait for a later post.

These three schools are remarkable examples of what can happen when you abandon false restrictions of what students are capable of achieving. They are all fee-paying, independent schools, but there’s much to learn, and much to be applied in the public sector, from what they are doing.

The next post will examine schools that straddle private and public sector divides.

September 23, 2017

Postcards From The Future

How well are nations preparing their young people for the future? In the face of unprecedented challenges, it’s fascinating to see how education debates, and government policies differ around the world. I’m fortunate enough to be able to work in a number of countries and, as I’ve been editing a book* specifically dealing with this issue, it’s very much at the forefront of my thinking.

How well are nations preparing their young people for the future? In the face of unprecedented challenges, it’s fascinating to see how education debates, and government policies differ around the world. I’m fortunate enough to be able to work in a number of countries and, as I’ve been editing a book* specifically dealing with this issue, it’s very much at the forefront of my thinking.

But I’m far from alone: the film Most Likely To Succeed; the XQ Super School movement; the Richard Branson funded BigChange.org project – these are just a handful of examples, where serious thought is being dedicated to educational transformation. And that’s not to mention a slew of books published recently. As I’m currently in San Diego, I jumped at the chance to meet with the author of one of them. Grant Lichtman’s new book is called Moving The Rock: Seven Levers We Can Press To Transform Education. It’s been described by Yong Zhao (himself an advocate of radical change) as ‘an inspiring call to action for all educators’. I’d agree with that assessment. Meeting Grant gave me a chance to understand where our respective countries sit in relation to what he describes as the three stages of transformation: accepting why change is needed; identifying what those change would look like, and understanding how that transformation can be achieved, at scale.

Some countries – some would argue that New Zealand, Canada and Finland would be prime examples – seem to be well past the why, and are even at a point of agreement on the what. Even the most forward-thinking countries struggle with the how, but the how only becomes concrete once you’ve agreed on the why and what. Grant asked for my assessment of where the UK sits on that continuum. My personal view, and that of most of my co-authors, is that we’re still stuck on the why – at least in England (overseas readers may need to be reminded that each of the UK countries has its own education responsibilities and policies, and they’re beginning to differ quite radically). The political discourse around education reform in England is mainly centred on ‘standards and structures’: how to raise existing standards through various structural models. Very few politicians are talking about whether those standards are still relevant now, let alone in the next couple of decades. We’re still witnessing the same old turgid Twitter disagreements on whether ‘skills’ matter, or whether kids still need knowledge. Traditionalists ‘call out’ progressives (and vice-versa) for cherry-picking evidence, to support one extreme or the other. Advocates cite best practice – hardly anyone is talking about next practice. Let’s be clear: best practice is only going to address what’s worked in the past, not what we need to be ready for the future.

Speaking to Grant Lichtman confirmed something that Sir Ken Robinson had said to me at the end of last year: that in the United States, the argument, around the need for educational change, is largely over. Both Ken and Grant work with superintendents all over the continent. Their clear view is that there is a strong consensus that the historical obsession with standardised testing, driven by ‘PISA Hysteria’, has failed. Grant also feels that there is a pretty strong consensus on what should replace the drilling of a ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum into young American minds – what has been described broadly as ‘deeper learning’. Now deeper learning comes in for a fair amount of criticism from traditionalists, but to me it’s simply a shorthand umbrella for a shift away from the superficial ‘covering’ of great chunks of curriculum, teaching to the test and assessing only the amount of knowledge that can be recalled in a timed test, in favour of greater depth of time on fewer curriculum areas, and applying that knowledge in authentic contexts. In short, it’s a response to the challenge that employers – particularly those in the rapidly expanding knowledge economies – are laying down: the world cares less about what you know, and more about what you can do with what you know.

If these two elements – the why and what – are taken as read, then the how is still formidable (because everything: curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, has to change) but it becomes achievable. So, we’re seeing initiatives spring up like the Mastery Transcript Consortium – a growing group of US high schools committed to finding an alternative to the narrow grading testimony that faces university admissions staff, one that reflects all of a student’s skills and dispositions.

So, if you believe that change is both urgent and inevitable, the question then becomes what does the future look like, and what can we do to move the conversation on?

For my part, I’m committed to trying to get as many people as possible to read our book, (and books like Grant’s) come to our event, and do what I can to get people in the UK to accept that we’ve been on the wrong track for a long time. Because if we can’t agree on the why, we’ll never get to the what and how.

If we want to see what the future looks like, I guess Silicon Valley is as good a place as any. The new economies, the growth jobs, all start there. It’s also the home of some of the most innovative schools in the world. So, I’m about to take a bunch of school leaders from several countries (though sadly none from the UK) on a 10-day tour of future-facing schools located in and around silicon valley. I’ll send as many postcards from the future as time allows, so watch this space.

* Education Forward: Moving Schools Into The Future is published by Crux Publishing on October 14th

July 10, 2017

Book Review: Valerie Hannon’s ‘Thrive’

A question not discussed often enough in school staffrooms is ‘what are we all doing here?’ The purpose of schooling is one of those rarely-visited assumptions: we all think we share the same mission but, on closer examination, those assumptions can frequently differ widely.

In Valerie Hannon’s* new book, Thrive: Schools Reinvented For The Real Challenges We Face the case is powerfully made that the point of schools is to create thriving societies: “education has to be about learning to thrive in a transformative world.” In the following 150 pages she takes the broadest of overviews, forensically analysing the scale and scope of those transformations – challenges that only our young people will be faced with (since baby boomers like myself won’t be around when the full implications of what we’ve created becomes clear). The threats of global warming, the rise of the robots and artificial intelligence, the religious and cultural tensions heightened by mass migratory populations – and lots more besides – are all familiar concerns in future-focussed books. What makes this book so important, however, is that each of the transformations is examined in the light of the implications for education, with a clear set of recommendations. Going still further, with the help of Amelia Peterson, Hannon has searched the planet looking for schools already successfully responding to these challenges. In doing so, any possible excuse that schools shouldn’t, nor couldn’t, be concerned with the bigger picture, is artfully demolished.

If the main driver for education reform is getting into the PISA top ten, can schools be blamed for putting on the blinkers and ignoring the predicted revolutions in how we will work, live and learn?And this is the critical point we’ve reached in education systems in developed economies: since most of the political and policy imperatives are fixated on performance, who is responsible for purpose?

To which one might answer ‘if not us, then who?’ and ‘if not now, then when?’

Hannon proposes that the re-conceptualising of school needs to happen on four levels:

Intrapersonal – creating a secure sense of self and wellbeing;

Interpersonal – respectfully engaging in learning and loving relationships;

Societal – navigating an uncertain, changing work landscape and reinventing authentic democracy;

Global – living sustainably, acquiring global competence.

Each of these is analysed in turn – the depth of research in this densly-packed book is impressive – and through a refreshingly humanist perspective. In many ways this book is simply about love – for elders, for communities, for oneself and, of course, for learning. It’s a measure of how fearful, how transactional and utilitarian learning has become, that one should be surprised by an educator calling for loving relationships as a key outcome of schooling. The reason why this book can’t be dismissed as a hippy alternative to the data-driven dominant narrative, is that Hannon shows, through the many descriptors of outstanding schools arould the world, that a more humanist vision isn’t an excuse for poor test scores – it can be the key to improved outcomes, as many of the schools highlighted have demonstrated.

It’s encouraging to see that conversations about how education can re-think its purpose to enable our current students to thrive, not just survive, this turbulent future, are starting to spring up all over the globe. Organisations like Big Change Foundation, Ashoka Foundation, The XQ Project, are merely the tip of an iceberg that is slowly moving the dial, filling the vacuum of vision left by governments enslaved by ‘deliverology’. But these conversations need to happen in every school staffroom, in every community centre and in every boardroom around the world.

We don’t need permission to re-imagine education so that our young people can face the future confidently, with the kinds of skills and understanding needed to solve the problems we face. We don’t need permission to rethink curriculum so that we foster global competence, learner agency, positive mental health, sustainable communities, entrepreneurship and, yes, academic achievement.

We can do this now.

*Full disclosure: Valerie is a friend and work colleague at the Innovation Unit UK. Allowing for that, I would have found this book to be an important contribution if she were a complete stranger.

June 11, 2017

“Our youth have sussed the truth, and they will not be crossed again.”

“Look at me – I’ve got youth on my side!” – That’s how Jeremy Corbyn responded to a question on his long-term intentions on TV this morning, following the sensational turnaround in Labour’s 2017 UK general election. I don’t know if it was a planned remark, but it was brilliant in its reflection on the energy that surrounded Labour’s leader through the final weeks of the campaign, and, more significantly, pointing to the seismic shift that took place in this election. It’s a shift that should make every political strategist (and educator) rethink their prejudices.

“Look at me – I’ve got youth on my side!” – That’s how Jeremy Corbyn responded to a question on his long-term intentions on TV this morning, following the sensational turnaround in Labour’s 2017 UK general election. I don’t know if it was a planned remark, but it was brilliant in its reflection on the energy that surrounded Labour’s leader through the final weeks of the campaign, and, more significantly, pointing to the seismic shift that took place in this election. It’s a shift that should make every political strategist (and educator) rethink their prejudices.

Because what we saw in this election was a massive turnout in the youth vote. And because almost every party other than Labour assumed that young people weren’t interested in registering, let alone voting, Jeremy Corbyn had a free run: thanks to organisations like Bite The Ballot, over a million 18-24 year olds registered in the last month of the campaign, and it’s estimated that over 80% of them voted, for the first time, and they nearly all voted for Labour.

How could the other parties ignore a demographic that had the potential to completely re-write the script? Simple. They fell for the false assumption that, because the youth vote had been so low in recent years, Generations X,Y, Z and whatever comes after Z (does it go back to A or what?) would rather stay in bed than exercise their constitutional rights. Of all the epic fails of this election campaign, this was the biggest. What the strategists failed to acknowledge was that the recent past saw the merging of party differences, blurred by a coming together around the political centre, that made it hard to tell the difference between them. ‘A plague on all your houses’ was young people’s response – except no-one was listening.

Well, they are now.

What we’ve seen, in elections in the US, Sweden, Finland, Italy and now the UK, is that when they are presented with a genuine political alternative to the dominance of neoliberal ideologies (as we saw in Obama, The Pirate Party, 5 Star and now Corbyn’s Labour) young people will re-engage with politics and the political process. Bigly. And the shock waves have already been felt in America as Democrats wonder, ‘why didn’t we do that?’

It’s too soon in the post-match analysis to say that the capture of the youth vote ensured Labour prevented a Conservative victory (not least because Labour’s campaign, and Theresa May’s so-called ‘dementia tax’, mobilised large numbers of seniors too) but the early estimates are heartening: in the UK 2005 election only 37% of 18-24 year-olds voted; in the 2015 election 43% of them turned out; in the EU referendum that figure rose to 64%. In the 2017 election it’s estimated that 72% of young people bit the ballot. That’s higher than the overall voter turnout of 68%. So can we please have an end to the ‘narcissistic, shallow, celebrity-obsessed’ stereotype of young people?

If Labour have shown that young people can be re-engaged in the political process, why couldn’t they be re-engaged in schooling? Turnout of those who describe their voting intentions as ‘engaged in school’ hovers around 30% in most developed economies. And, just as we write off political engagement, we tend to write off school engagement – ‘they’re not there to enjoy themselves’ we say. ‘Learning is hard work – get used to it’, we say. ‘You can either be engaged, or achieve’, we say.

But do we ever listen to what they think?

After 30 years of working with young people, I’m convinced that all we have to do is craft a curriculum that speaks to their solemn responsibility – to fix some of the most pressing environmental, social, economic and political problems the planet has ever faced, within their lifetime – and we’ll have their engagement, and we’ll have their attention.

At the end of my book, OPEN, I wrote this:

“I’m personally thankful that so many young people, despite the hand they’ve been dealt, are so lacking in cynicism, and so selfless in their determination to find new answers to the age-old question: how shall we live? If the 1980s spawned the ‘me’ generation, driven by material need, they are being followed by the ‘we’ generation, driven by a set of values and ethics that put us to shame. All we really have to do is not get in their way.”

The events of the past week have demonstrated that we abandon hope when we dismiss the opinions of our young people, and if it takes a political upheaval – because make no mistake, that’s what has happened – to get the establishment to take their views, hopes and dreams, seriously, then so be it. They will ignore them at their peril in the future. Something has shifted, and it can’t be put back, as Mancunian poet, Tony Walsh movingly encapsulated in a poem in today’s Guardian newspaper:

March 22, 2017

Education: How We Should Seek To Understand While We Condemn The Westminster Attack

People are still around who lived through the Blitz of London during the Second World War, and I’ve always been proud of my country’s stoicism, so things will get back to normal with the minimum of fuss as they did after the 7/7 bombing. The reaction tonight from Donald Trump Jr was less restrained. He quoted an old interview with London Mayor (and Muslim) Sadiq Kahn: “You have to be kidding me?! Terror attacks are part of living in the big city, says London Mayor Sadiq Khan.” Well, actually, no. What Khan actually said was that we have to get used to the threat of terror attacks in big cities.

People are still around who lived through the Blitz of London during the Second World War, and I’ve always been proud of my country’s stoicism, so things will get back to normal with the minimum of fuss as they did after the 7/7 bombing. The reaction tonight from Donald Trump Jr was less restrained. He quoted an old interview with London Mayor (and Muslim) Sadiq Kahn: “You have to be kidding me?! Terror attacks are part of living in the big city, says London Mayor Sadiq Khan.” Well, actually, no. What Khan actually said was that we have to get used to the threat of terror attacks in big cities.

And we do. So, I was glad to see journalist Ciaran Jenkins report: “Khan is right. These things happen. We fight against them. But we don’t wildly over-react or let them change our way of life,” said Tom Coates, from London, adding that he had lived through IRA bombings and the 7/7 attacks on the London Underground.”

As I write, this story is unfolding, so it would be foolish to speculate – as Channel 4 catastrophically did – on the attacker’s identity. Whether Donald Trump Sr will use the attack to support his ‘Islamic Ban’ is not yet known, but if it turns out to be that, as in most terrorist attacks in the UK and USA, the perpetrator turns out to be a national citizen, then a travel ban isn’t going to make much difference.

Don’t get me wrong – for the people caught up in this horror, this was a terrible event. But looking for simplistic, knee-jerk solutions isn’t the way forward. The UK terrorist level was already at ‘severe’. Sadly, when an automobile becomes a lethal weapon there’s literally nothing security forces can do to prevent these kind of attacks.

So, what can we usefully do?

It seems to me that our focus needs to shift towards education as the best means of prevention. And I don’t mean the ‘de-radicalisation’ of returning ISIS freedom fighters – by then it’s too late. No, the process needs to start in schools, and in communities. The UK has followed many developed countries in recent years in moving away from an official policy of ‘multiculturalism’. Whatever one thinks of the supposed failings of multiculturalism, I’d like to ask: do we feel any safer as a result of this shift? Equally, do our children understand ‘the other’ in the ways that they used to do under the multicultural policy?

The sad thruth is that, in the narrowing of curricula, we have lost the space to talk about empathy, cultural awareness and the possible roots of terrorism, because we’re desperate to get our Numeracy and Literacy scores up. At the same time, our 24/7 news media only reinforces the notion that, if you’re a young British kid whose religion happens to be Muslim, your sense of belonging matters less than preserving the pillars of ‘Britishness’. It’s been striking to see how much of the TV coverage so far has been focussed upon the attack on the Palace of Westminster, (and by inference, democracy), at the expense of the fate of 40 people who happened to be walking across Westminster Bridge at the wrong time.

A woman lies injured after a shooting incident on Westminster Bridge in London, March 22, 2017. REUTERS/Toby Melville

Let me speak plainly. In the face of one man’s hatred, our ONLY response has to be love. For each other, and towards those we never speak to or socialise with.

In a strange coincidence, at lunchtime today I watched a news item about the anniversary of the bombing of Brussels airport. I was there just a few days ago, having worked at the Learning By Design conference at the International School of Brussels. What struck me so forcibly during that week-end was the emphasis upon two things: the UNESCO goals, and the benefits of internationalism. I was honoured to work with students from a range of countries who were creating socially purposeful global innovations that help bring us together, not drive us apart. And, throughout the whole event, there was a palpable, and visible, sense of love between delegates, teachers and students, who came from all over the planet to learn together and appreciate our differences.

The kinds of attacks we’re now witnessing in capital cities tend to come from ‘lone-wolfs’, inspired by copycat attacks, rather than orchestrated strategies from terrorist groups. So, if we can’t stop people from renting a car and driving it into a crowd of people, can we begin to see our schools as the best hope we have of preventing the sense of isolation that seems to fuel these lone wolf attacks?

And can we make tolerance, understanding, and love for ‘the other’, a cornerstone of our schools’ purpose?

December 8, 2016

PISA Hysteria Hits Record Levels Globally

With the release of the 2015 OECD rankings in literacy, numeracy and science, this week has predictably seen a fresh – and more virulent – outbreak of PISA hysteria.

The OECD really have to ask themselves if the monster they’ve created should now be euthanised. PISA has become a nuclear bomb without a guiding system. It’s a cherry-pickers charter par excellence, and if a few – well, a tsunami actually – of misleading tweets were all we had to put up with, that would be one thing. But in an excellent opinion piece in the TES,. William Stewart points to how the PISA juggernaut now not only presumes to tell governments what’s wrong with their education systems, through a series of dubious correlations, it’s now telling them what they need to do to make things better. I know people never click on links, so let me quote from Stewart’s article:

“And while countries like Germany and Japan may have changed education policy because of information from international surveys, there also seems to have been a shift to the point where governments are starting to see the survey ranking as an end in itself, as a key policy goal.”

“In Wales, the government is intent on “embedding Pisa skills in Welsh education” and has enlisted Schleicher to help explain to its teachers why Pisa is “so important” and how “GCSEs and the curriculum in Wales” are being changed to test “Pisa Skills”.

Yes, ‘PISA Skills’ is now officially a thing…..

“…many of the test scores used to calculate Pisa rankings are not from real pupils answering questions, but from a computer running a statistical programme to work out what the probable answer of a pupil who didn’t actually take the test would have been”

I confess that was news to me…

“it is potentially misleading for Pisa to recommend classroom strategies at all because the study does not question teachers about their methods. It relies instead on questionnaires filled in by pupils.”

What???

Apparently so. The categorisation of teaching strategies being adopted, and now judged, is not determined by someone from PISA observing teachers. It’s not even gleaned from teacher’s self-description. No, it’s taken from a 9-item agree/disagree questionnaire, filled in by students.

Here – as far as I can discern – are the items:

Those that indicate Teacher-Directed Strategies –

At the beginning of the lesson, the teacher presents a short summary of the previous lesson;

The teacher asks me or my classmates to present our thinking or reasoning at some length;

The teacher sets clear goals for our learning;

The teacher asks questions to check whether we have understood what was taught;

The teacher tells us what we have to learn.

I know plenty of teachers who use project-based learning, that would tick every one of those boxes. So, are they really the indicators of ‘teacher directed strategies (as decided upon by students, remember)?

The items that indicate ‘student-oriented strategies’ are only marginally less contentious:

6. The teacher assigns projects that require at least one week to complete;

7. The teacher asks us to plan classroom activities or topics;

8. The teacher has us work in small groups to come up with joint solutions to a problem or task;

9. The teacher gives different work to classmates who have difficulties and/or who can advance faster.

The judgement of Twitter, based upon these highly questionable definitions of ‘teacher-directed’ and ‘student-oriented’ strategies was that successful countries favour the former, not the latter.

Except:

The Singaporean government committed itself to project work and problem based learning in 2000. Project Work has been part of the curriculum for more than 10 years at both Primary and Secondary levels;

In South Korea, ‘The Ministry of Education has tried to reform upper secondary school instruction to some degree, encouraging teachers to incorporate inquiry-based learning and problem solving… teachers reduce direct instruction and integrate multiple subject areas into group or individual projects. This method gained traction after success in independent schools, and is now used by many public schools in South Korea, with government support.”

Finland has long adopted ‘student-oriented strategies’ and recently introduced cross-disciplinary approaches through its phenomenon based learning;

Canada ‘Following a series of reforms in the 1960s and 1970s, the method of instruction in Canada changed from primarily rote learning to one focused on child-centered learning.’

In Hong Kong ‘At all levels of compulsory education, the government promotes “life-wide learning.” This philosophy promotes learning in “authentic environments” such as science museums or farms’

(Source: Centre on International Education Benchmarking)

These countries, it seems to me, are behaving in their policy-making, the way all of the good teachers that I know behave in their classrooms. They’re not seeing good teaching as either ‘traditional’ or ‘progressive’. They’re blending teacher-led, and student-centred, not trying to decide between them. The extreme polarisation we’re currently witnessing between ‘Traditionalists’ and Progressives’, is incredibly damaging and not representative of the teaching profession as a whole. Because the PISA hysteria that has politicians all around the world spouting nonsense, arguing for the end of inquiry-based approaches, and a return to direct-explicit instruction, sees the world in black-and-white. This polarisation ignores the reality of what goes on in the leading nations, and assumes that getting to the top of PISA is the end goal, in itself, of a successful education system. As today’s piece in The Conversation makes clear, be careful what you wish for. Singapore’s success is more likely due to the fact the 80% of primary, and 60% of secondary students, get private tuition after school. Believe me, I’ve seen them on the Singapore subways, exhausted after yet another 12-14 hour day. Is that what we want for our kids?

In my view (and it’s a view shared by an increasing number of educators, but sadly nowhere near enough politicians) is that PISA only conclusively tells us one thing. It tells us about the cultural attitudes towards education in OECD countries. As John Jerrim elegantly demonstrated, there isn’t anything inherently wrong with the Australian education system – not when you look at the scores of Asian students who have gone through it. Jerrim looked at the performance of 14,000 Asian/Australian kids who took the PISA 2012 maths test. These students had spent their entire academic career in Australian schools. Their Maths scores were higher than ANY other OECD country (other than Shanghai, and that’s never been a country).

It’s been a similar story in the UK (and probably in the US, I haven’t checked): Asian kids excel, even when they’re not being educated in Asia. Cultural attitudes- and pressure- to success in school makes the difference. Despite this, we’re seeing the triennial casting around in both the UK and Australia for someone to blame. If PISA is the sole purpose of education, don’t blame the schools in countries like the UK and Australia, blame parental attitudes in the West. But how did the UK become the 5th biggest economy in the world – without the benefit of rich natural resource – if it’s so rubbish at Maths, English and Science? Similarly, how has the US consistently been the innovation hothouse of the world, and yet so consistently average in PISA assessments? If the purpose of education is to score well in tests, go ahead and judge schools and systems by PISA rankings. But if the purpose is to build vibrant economies, and/or happy, informed citizens, equipped for the future, could we please find a different set of measures?

November 5, 2016

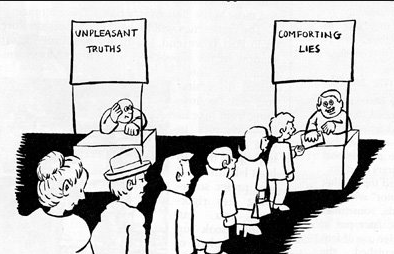

Lies, Damn Lies, And Conscious Misrepresentation of Evidence

Credit: S H Chambers

An earlier post of mine, on ‘what counts as evidence’, generated a healthy debate, and I thought I could leave the thorny problem of ‘what works’ in education for a while. Maybe lighten the mood with a blog about the all-out assault on the judiciary in post-Brexit Britain, or what’s an appropriate response to a Donald Trump presidency, something like that.

But the ‘evidence’ issue reared its contentious head again yesterday, November 4th, so The Donald might have to wait.

The flashpoint was the publishing of a report by the Educational Endowment Foundation (the UK equivalent of America’s What Works Clearinghouse) on the impact of Project-Based Learning on literacy and engagement.

The Times Educational Supplement was the first to claim “Exclusive: Project-based learning holds back poor pupils”. And the predictable social media onslaught ensued:

It soon became abundantly clear that hardly any of the Tweeters had bothered to read the actual report. In fact, I doubt very much that many of them had even gone beyond the abbreviated version of the TES article, the fuller version of which is only available on subscription So, before we go any further, please spend 5 minutes reading the EEF summary here. Better yet, read the full report.

The summary doesn’t get off to a great start with an bizarrely restrictive definition of PBL:

“Project Based Learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that seeks to provide Year 7 pupils with independent and group learning skills to meet both the needs of the Year 7 curriculum as well as support their learning in future stages of their education.”

But let’s move on to the gist of the conclusions:

“Adopting PBL had no clear impact on either literacy (as measured by the Progress in English assessment) or student engagement with school and learning.” Perhaps mildly surprising as PBL is often touted – by people like me – to enhance student engagement. Otherwise, nothing to see here.

“The impact evaluation indicated that PBL may have had a negative impact on the literacy attainment of pupils entitled to free school meals. However, as no negative impact was found for low-attaining pupils, considerable caution should be applied to this finding.”

I confess I’ve read this statement repeatedly, and I’m still none the wiser. Are free school meals students therefore not ‘low-attaining’? If considerable caution should be applied, why draw the conclusion in the first place?

This was the focus of the TES headline. Their journalist clearly read the full EEF report, but didn’t think it their responsibility to draw attention to the caveat ‘overall, the findings have low security…47% of the pupils in the intervention and 16% in the control group were not included in the final analysis. Therefore there were some potentially important differences in characteristics between the intervention and control groups. This undermines the security of the result. The reason that so many pupils from schools implementing PBL are missing from the analysis is largely due to five of these schools leaving the trial before it finished. The amount of data lost from the project (schools dropping out and lost to follow-up) particularly from the intervention schools, as well as the adoption of PBL or similar approaches by a number of control group schools, further limits the strength of any impact finding.”

So, almost half of the schools had to drop out (for reasons which we’ll come to in a moment). Furthermore, the intervention period was meant to be two years but, due to funding constraints, this was halved. This is significant because most PBL experts agree that it takes 3-5 years before teachers really feel confident delivering a different pedagogical approach, and can therefore expect high quality student outcomes, whereas one can assume that the control group of schools have been working in their ways for some considerable time.

And if that’s not enough to cause doubt, consider this from the report:

“ for some that did not get allocated to the intervention group, faithfully adopting the control condition was seen as being detrimental to their pupils’ learning and therefore some of these schools chose to implement a version of PBL anyway.”

(Full disclosure: I can confirm this took place. Although I’m a Senior Associate at the Innovation Unit, who managed the trial, I was not part of the team. I do, however train schools in the use of Project-Based Learning. I discovered at the end of a training event that the school I’d been training were part of the control group and were intending to introduce PBL to their students. Contamination of evidence is anathema to educational researchers and further undermines the usefulness of the conclusions.)

Another central tenet of randomised control trials is that like is compared with like: if you want to know whether an intervention will improve literacy scores, you should have schools that were comparable before the intervention began. According to the Innovation Unit blog post in response to the report: “8 of 11 schools in the study were ‘Requires Improvement’ (an OFSTED categorisation indicating cause for concern) or worse (national average is 1 in 5)…The control group were stable in comparison, with 8 of 12 schools Good or Outstanding” .

So, here’s the nub of it: the newspaper article claimed that the report demonstrated that “FSM pupils in project-based classes made three months’ less progress in literacy than their counterparts in traditional, subject-based lessons.”

But this was based upon literacy data from schools – 80% of which would have already had poorer test scores than most of the control group schools. Is it possible, therefore, that the kids tested might have actually been further than 3 months behind their control group counterparts, without the PBL intervention?

Let’s use a simpler analogy in order to highlight this flaw: If you feed me anabolic steroids for a year, I’ll still come in a long way behind Usain Bolt in a 100m race. Surely a more sensible test would have been to see if my own personal times improved after the ingestion of drugs, not whether I was able to beat someone already faster than me?

Some on Twitter justifiably asked why was almost half of the data missing from the intervention schools, but not the control group? It turns out there were a variety of reasons, most of which point to the difficulty of carrying out trials in the fear-driven English schools system. 5 of the 12 intervention schools withdrew during the trial. 3 had a change of headteacher (presumably in response to OFSTED judgements), 2 were taken over by academies. 1 withdrew after the trial was cut from 2 years to 12 months. One school refused to submit its students to the test, arguing (with some justification) that you can’t hope to see improvements in literacy scores 12 months after introducing PBL.. If you, as a leader, were facing future closure if results didn’t improve, would you introduce a significant change like project-based learning, or knuckle down, and overdose on test-prep? Yep, me too. So, does it make sense to study the impact on such schools?

Before I get on to the two ‘J’Accuse’ parts of this post, allow me to share a few quotes from the evaluators report:

“ i t is not possible to conclude with any confidence that PBL had a positive or negative impact on literacy outcomes”

“ schools reported finding positive benefits from the programme in terms of attainment, confidence, learning skills, and engagement in class”

“ the Innovation Unit’s Learning through REAL Projects implementation processes were particularly effective for the target (that is, willing and with the capacity) schools, and the feedback from those schools was almost entirely positive.“

“The need for improving skills appropriate for further study and those valued by employers in the modern workplace (a central aim of PBL) has not diminished, but probably increased. This study picked up the value of these skills to pupils’ learning and future potential through the process evaluation, but was not able to measure these skills as an outcome.”

Were any of these quoted by the TES? Of course not. I realise that “Study Doesn’t Prove Much Of Anything” is a kind of headline more suited to The Onion than the TES, but journalists have a responsibility to provide balance, especially in the education press, as we’re living in an evidence-based era. If they don’t provide that balance, we may as well just forget about truth and see who can shout the biggest lie. The evaluators, it seems to me, did a good job in presenting a fair and balanced assessment, working within the constraints of a difficult set of circumstances, on a project that probably should have been curtailed when so many schools dropped out.

It’s just a pity that the ideological bias of our media sought to significantly misinterpret it.

Which brings me to my second accusation. I don’t think I’m being unfair when I say that, in the increasingly fractious educational debate between ‘traditionalists’ and ‘progressives’, there are a greater proportion of traditionalists who say that we should objectively look at the evidence, and make informed policy and practice decisions, on the facts, not misinterpretations.

So, it was particularly disappointing to see some of those same people jump on the TES headline, rather than reading the evaluators report. Sadly, this includes Nick Gibb, Minister of State for School Standards:

and Sam Freedman, Director of Teach First:

and SchoolsImprovementNet:

And a host of others on Twitter.

Rachel Wolf, of Parents and Teachers for Excellence, was quoted in the TES article (because I’m sure she’d read the full report), citing students doing a project on slavery, baking biscuits, as evidence that PBL taught the wrong things. I shall henceforth remember her fondly as ‘rigorous Rachel’. In their defence, the TES at least shared quotes from some of the intervention schools. One of these schools that’s presumably been failing their Yr 7 students was Stanley Park High School. In an unfortunate disjuncture, this same school had just been awarded 2016 Secondary School of the Year by…the TES. You couldn’t make it up. Oh, wait, they just did.

In my attempts to get some of the above to read the original evaluators report, in full, before exercising their prejudices, I was accused of dismissing the evidence. I’m not. I’m the first to say that the evidence based for PBL is weak (though stronger than many claim, and the evaluators have done a good job in presenting the key messages from a literature review). Many people who see very positive impacts of PBL (in extraordinary schools like Expeditionary Learning, High Tech High and New Tech Network in the USA) are very anxious to see large-scale, reliable research emerge on the breadth of impact of PBL.

But, until we have that, can we stop hysterically distorting what little evidence we have? The rising popularity of PBL around the world has enthused and revitalised legions of classroom teachers. Until we’ve got some conclusive evidence that it’s not working, can we allow them to exercise their own professional judgement, please?