Lydia Gastrell's Blog

October 8, 2018

Finally Back!

It has been quite a while since I posted anything or got around to dealing with the unfortunate closure of Loose Id. But I finally have things in order and, as of yesterday, the Indulgence Series is once again available! I am furiously working on Indulgence #3 (tentatively titled One Kiss), and hope to have it up and published by the end of the year.

As for now, One Indulgence and One Glimpse are available on Amazon, with other retailers to be added soon. I want to thank everyone who followed this series and were so patient back during the original publishing. And, if you wrote any reviews for either book when it was still being held by Loose Id, I would ask if you consider posting them again on the Amazon page, since the closure of Loose Id means we lost all our reviews and links. We're starting from scratch now in that regard. Happy reading!

One Indulgence (Indulgence, #1)

One Indulgence (Indulgence, #1)

2nd Publication: October 8th, 2018

Length: 89K words

When Henry Cortland, the Earl of Brenleigh, comes to London to fulfill his duty and take a wife, he also decides to first fulfill his most secret and suppressed desires. He wants to spend just one night with a man. A sultry encounter with a handsome stranger surpasses all his hopes, leaving him certain that he will live off the memories for the rest of his life.

Lord Richard Avery has grown tired of his endless string of casual relationships, yet an argument with his lover sends him right into the arms of a total stranger. But Henry is not like any lover he has ever had, and the attraction between them is more than physical. Richard wants more, but can their mutual attraction overcome Henry's family obligations and sense of duty? Can Richard convince him to follow his heart rather than the demands of family and title?

Available at: Amazon, (other retailers to be added soon) One Glimpse (Indulgence, #2)

One Glimpse (Indulgence, #2)

2nd Publication: October 8th, 2015

Length: 119K words

For years Sir Samuel Shaw has secretly lusted after the handsome and popular Lord John Darnish, a man known for his good humor, expert riding prowess, and very female mistress. Certain that John is an unattainable fantasy, Sam is shaken when an accidental discovery reveals John might not be as unattainable as he once thought. But what is possible is not always likely, and Sam finds himself trapped between keeping a friend and risking everything for the unlikely hope of something more.

John is terror struck when his drunken mistake threatens to shatter the double life he has worked so hard to maintain. His terror soon turns to hope when he finds himself drawn to Sam, who he is sure does not share his interest in men. But subtle things cause him to second guess, and fear that his hopes are making him see what he wants to see.

Sam's risks and John's hopes turn futile, however, when blights from Sam's past resurface to threaten them and Sam's family. Can Sam choose between the love he has always wanted and the security of his family, or will forces outside his control hurt all the people he holds most dear? \

Available at: Amazon

As for now, One Indulgence and One Glimpse are available on Amazon, with other retailers to be added soon. I want to thank everyone who followed this series and were so patient back during the original publishing. And, if you wrote any reviews for either book when it was still being held by Loose Id, I would ask if you consider posting them again on the Amazon page, since the closure of Loose Id means we lost all our reviews and links. We're starting from scratch now in that regard. Happy reading!

One Indulgence (Indulgence, #1)

One Indulgence (Indulgence, #1)

2nd Publication: October 8th, 2018

Length: 89K words

When Henry Cortland, the Earl of Brenleigh, comes to London to fulfill his duty and take a wife, he also decides to first fulfill his most secret and suppressed desires. He wants to spend just one night with a man. A sultry encounter with a handsome stranger surpasses all his hopes, leaving him certain that he will live off the memories for the rest of his life.

Lord Richard Avery has grown tired of his endless string of casual relationships, yet an argument with his lover sends him right into the arms of a total stranger. But Henry is not like any lover he has ever had, and the attraction between them is more than physical. Richard wants more, but can their mutual attraction overcome Henry's family obligations and sense of duty? Can Richard convince him to follow his heart rather than the demands of family and title?

Available at: Amazon, (other retailers to be added soon)

One Glimpse (Indulgence, #2)

One Glimpse (Indulgence, #2)

2nd Publication: October 8th, 2015

Length: 119K words

For years Sir Samuel Shaw has secretly lusted after the handsome and popular Lord John Darnish, a man known for his good humor, expert riding prowess, and very female mistress. Certain that John is an unattainable fantasy, Sam is shaken when an accidental discovery reveals John might not be as unattainable as he once thought. But what is possible is not always likely, and Sam finds himself trapped between keeping a friend and risking everything for the unlikely hope of something more.

John is terror struck when his drunken mistake threatens to shatter the double life he has worked so hard to maintain. His terror soon turns to hope when he finds himself drawn to Sam, who he is sure does not share his interest in men. But subtle things cause him to second guess, and fear that his hopes are making him see what he wants to see.

Sam's risks and John's hopes turn futile, however, when blights from Sam's past resurface to threaten them and Sam's family. Can Sam choose between the love he has always wanted and the security of his family, or will forces outside his control hurt all the people he holds most dear? \

Available at: Amazon

Published on October 08, 2018 15:45

October 31, 2016

A Writer's Defense of Bitterness

How a legitimate character trait got a bad rap, and why we shouldn't be afraid to use it.

How a legitimate character trait got a bad rap, and why we shouldn't be afraid to use it. We've been told our whole lives that being bitter, being petty, holding on to hurt feels is bad, bad, bad. This is probably why in fiction of all genres bitterness is an emotional state left mostly to antagonists, or worse, outright villains. The good, sweet, kindhearted protagonists are supposed to forgive, forget, rise above, get zen with the situation, because forgiveness is divine, etcetera, etcetera.

Most of us have encountered the anti-bitter/pro-forgive mantra in our personal lives. Someone does something to harm you (this scenario could be any number of things, from mild to heinous. Take your pick) and after a while your family, your friends, pretty much everyone will start to get "fed up" with your feelings. This is especially true if the person who hurt you is a mutual friend or relation and your bitterness is causing discomfort for them. Yes, we've all heard it:

"You need to get over that!" "You need to stop this!""He/she/they said they were sorry already!"

Now, if someone is making an active nuisance of themselves with regard to a slight—constantly bombing conversations with it, insisting mutual friends/family "take your side", etc.—there is room for issue. But where this situation, and the situation in fiction, gets hairy is when people start demanding you smile and pretend to be happy for the benefit of others...or for the benefit of plot.

In the popularity contest of hurt vs. guilt, guilt always seems to win.

In the popularity contest of hurt vs. guilt, guilt always seems to win."So-and-so feels really bad about this. You need to give forgiveness."

"He feels just terrible. Don't you think he's suffered enough?"

...and finally, the death knell...

"You should forgive for you. It's not good to hold on to stuff like that."

The last is where forgiveness dives down the slippery slide of being an outright lie. Anyone who believes that saying "I forgive you" out loud is a pure mirror of how the person saying it really feels inside, is kidding themselves. Verbally issuing forgiveness is not always for the victim's benefit. It's for the antagonist or for their mutual friends who no longer want to deal with the situation. Sometimes, the peer pressure from society is so great in regards to forgiveness, that people will publicly offer what they don't really feel for the purposes of virtue-signaling. [It should be noted that while virtue signaling is a relatively new term, and is often used derisively toward the progressive left, the act itself has always existed. If you've ever spent much time in an evangelical church, you'll know that virtue signalling is a universal group trait, though it used to be called being sanctimonious.]

Regardless of the motivations, society encourages situations where the victim is the one who should change, the victim is the one who should adapt, the victim is the one who needs to get zen with the situation and rise above their feelings. In fact, if one persists in withholding forgiveness--either explicit or by simply "acting like it didn't happen"--people will often turn the victim into the new perpetrator. After all, making someone feel guilty is just the worst, isn't it? Hurt vs. Guilt...guilt takes the win.

By now you're probably asking, What does this have to do with writing?

By now you're probably asking, What does this have to do with writing? In fiction, bad things happen to protagonists and they grin and take it. Very often, this bad, enraging event happens early on and serves as the launching event for the rest of the plot. The younger son who is left destitute when his elder brother inherits everything, the woman who is foisted off into an arranged marriage for her father's benefit, the store owner whose business and life is ruined by the competitor across the street (hello there You've Got Mail); the potential is almost endless. But what almost invariably happens is that this initial conflict is swept aside, both emotionally and for plot driving purposes, leaving the protagonist to exist in the situational aftermath with an artificially clean emotional slate—the younger son struggling to make it on his own, the woman finding contentment or love in her arranged marriage, the friggin' shop owner just getting a different job and falling in love with the guy who ruined her.

The bad event and the antagonist responsible disappear into the night, and the protagonist has their cute but unrealistic moment of semi-forgiveness in the form of internalized resignation:

"There's nothing I can do about it now" "No choice but to make the best of it.""I'm better than this, rise above..."[Oh, how many lovely plots are destroyed in this manner! Don't even get me started on how much I love the Sense & Sensibility fan-fiction in which the impoverished Dashwood women exact sweet revenge on their idiot brother and his greedy wife.]

"There's nothing I can do about it now" "No choice but to make the best of it.""I'm better than this, rise above..."[Oh, how many lovely plots are destroyed in this manner! Don't even get me started on how much I love the Sense & Sensibility fan-fiction in which the impoverished Dashwood women exact sweet revenge on their idiot brother and his greedy wife.] Instead of always glossing over wrongful events done to protagonists, why not use them instead? Let your character be bitter, let them stew in it. What the hell, let them become damn near pickled from all that salt, because when things change for them (if they do) and they have a reason to no longer feel bad, the prize will be so much better. What's a bigger win? Happiness after meh resignation, or happiness after bitter rage? All of us writers know that the bigger the obstacle, the greater the happy ending, and bitterness is one of the greatest internal obstacles available to us.

Also, we shouldn't forget the plot driving power of bitterness. We want our characters to be the drivers of plots, not just objects that respond and react to events around them. Having characters shed or 'get over' emotions with unrealistic speed or saint-level oneness robs the writer of valuable plot fuel.

But what if my character is unlikable?

I will admit, I have a personal ax to grind with the notion of the always perfect and likable protagonist. Insisting that a protagonist always be likable to begin with is short sighted. For one thing, no type of person is likable to everyone. Where one person sees kindness and altruism, another sees compensation and desperation. Where one person sees strength and dignity, another sees arrogance and snobbery. You can't control how every reader is going to take your protagonist, so why hedge your bet by bleaching them into this emotionally sterile dummy that doesn't make any decisions or influence events based on their own emotions and desires?

I will admit, I have a personal ax to grind with the notion of the always perfect and likable protagonist. Insisting that a protagonist always be likable to begin with is short sighted. For one thing, no type of person is likable to everyone. Where one person sees kindness and altruism, another sees compensation and desperation. Where one person sees strength and dignity, another sees arrogance and snobbery. You can't control how every reader is going to take your protagonist, so why hedge your bet by bleaching them into this emotionally sterile dummy that doesn't make any decisions or influence events based on their own emotions and desires?[The unlikable protagonist should not be confused with an anti-hero, which a different animal all together.]

So, what does bitterness look like?

Well, it doesn't look like the pinched-faced, scowling monster that it is often portrayed as when applied to villains. Bitterness is an internal emotional state, not an outward action or behavior, but it is often confused as such. One can feel bitter with others having no idea. Your character's behavior is not always the same as how they feel inside, unless you're writing children with no personal control over themselves.

Balzac portrays Bette as heinously ugly,

Balzac portrays Bette as heinously ugly,following the shallow tradition of unlikable

characters being physically unappealing.

Balzac's novel Cousin Bette is my favorite example of a character driven plot relying heavily on bitterness, although his descriptions of Bette are precisely the nasty, pinched-faced visage I mentioned. Balzac did not see his Bette character as a justified protagonist; he modeled her after three women from his own life whom he despised, so needless to say his demonstration of bitterness and anger in Cousin Bette is heavily colored...despite the character having many MANY reasons to be pissed off and vengeful. Full Disclosure: I root for Cousin Bette every time ;)

So, while Cousin Bette is my favorite example of character/emotion driven plot, it is also a perfect example of why bitterness as a character trait is so heavily disliked and talked down. The prose leaves the reading in no doubt that Balzac disapproves of Bette; she is ugly, demonic, acidic, single minded, etc. One of the objects of Bette's rage is her cousin who ruined the family by lavishing wealth on his mistress, a point that Balzac barely gives a moral shrug. The suggestion being that Bette's feelings are inappropriate regardless of the level of hurt and provocation going on around her. She should accept and/or forgive no matter what.

Balzac is not alone in this. Just a simple search of the term bitterness on brainyquote results in page after page of pro-GetOverIt.

Balzac is not alone in this. Just a simple search of the term bitterness on brainyquote results in page after page of pro-GetOverIt.As far as the traditional use of bitterness in literature, it has a long history of belonging to mean, manipulative female characters. The sexist overtones of this are pretty obvious. After all, making it a moral imperative that women accept and forgive wrongs done to them has a pretty long history of benefiting men, right? No man wants to be glared at and made to feel guilty after he just got home from spending the day with his mistress, after all!

So, it is understandable why there are countless feminist blog posts out there specifically telling writers to stop writing bitter female characters. We've been trained--by a long history of male writers--to view bitterness as a terrible thing exercised by women, and surely we want to get away from that, right? I disagree, because to do so is merely to fall into the very trap they laid, the trap that says women should never feel bitter. I find this odd. Bitterness is a real emotion that men and women have. Instead of instructing people to strip female characters of a real emotional state, maybe we should encourage writers to start applying it more often to male characters as well, and to do so in ways that don't come out as "justifiable vengeful", which is the way male bitterness is often treated in literature.

So, it is understandable why there are countless feminist blog posts out there specifically telling writers to stop writing bitter female characters. We've been trained--by a long history of male writers--to view bitterness as a terrible thing exercised by women, and surely we want to get away from that, right? I disagree, because to do so is merely to fall into the very trap they laid, the trap that says women should never feel bitter. I find this odd. Bitterness is a real emotion that men and women have. Instead of instructing people to strip female characters of a real emotional state, maybe we should encourage writers to start applying it more often to male characters as well, and to do so in ways that don't come out as "justifiable vengeful", which is the way male bitterness is often treated in literature.  So, unless you're writing a tragedy with sanctimonious overtones like Cousin Bette, or a moralizing tale of revenge gone mad like Moby Dick, you don't want a bitter protagonist, right? And especially not in romance, surely! I disagree, because we've been given an exaggerated, villainous impression of what bitterness is.

So, unless you're writing a tragedy with sanctimonious overtones like Cousin Bette, or a moralizing tale of revenge gone mad like Moby Dick, you don't want a bitter protagonist, right? And especially not in romance, surely! I disagree, because we've been given an exaggerated, villainous impression of what bitterness is.

An hilarious book, btw.

An hilarious book, btw.Available HERE

What bitterness really looks like is just baggage. A character with baggage, whose past is continuing to influence their emotions and decisions in a generally negative way, is, despite semantics, bitter.

To draw from my own writing, Sam Shaw in One Glimpse has a ton of baggage and is absolutely bitter. There is no denying that word usage. His anger toward Henry and the events that occurred due, in part, to Henry's actions have colored and influenced Sam's entire life. His disbelief that anyone could ever truly love him, his reluctance to get too attached to anyone, are not character traits that just magically bloomed from thin air. They exist because he is bitter and hung up on his past. If I had given Sam an unrealistic zen moment of "life throws things at you and you just have to overcome them", his entire story would have been different and probably boring as hell (though my belief the book isn't boring is definitely a personal bias, lol. I encourage readers to decide.)

So, even though the title of this post is "In Defense of Bitterness", what I'm really defending and promoting is that bitterness, for the purposes of writing, be overcome and dealt with realisticallyand with justification. The writer should not view their character's realistic emotions as a plot hindrance; they are the plot. If your novel ends with the protagonist still feeling bitter enough to be hung up on it, that's fine too...it just means you've probably written a tragedy or a cautionary tale rather than a romance, and I love those too.

Published on October 31, 2016 15:00

April 5, 2016

Poor Mr. Collins, Part 1 - Screen Portrayals of the Character

The Popular Portrayal of Mr. Collins

Mr. Collins is not supposed to be liked. Readers and movie watchers alike are supposed to be empathizing with the heroine Elizabeth Bennet, and since her dislike of Mr. Collins is so extreme—far too extreme, in this author's opinion—movie makers seem to have gone to extra lengths to make certain the audience really, really dislikes Mr. Collins. They did this through the use of various negative male stereotypes such as age, height, presence, and even allusions to lack of masculinity. And since human beings are visual creatures, our popular impressions of Mr. Collins have been formed by the movies much more than they ever were by the book.

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

In the 1940 version starring Lawrence Olivier as Darcy, Mr. Collins is played by Melville Cooper. Cooper takes on the role at the age of 44, playing a tall, bombastic, attention seeking Collins. Cooper wore stage makeup during filming that was intentionally designed to make him look older than his 44 years. Now, one should never expect or demand precise casting in movies. Casting directors have to look for talent, availability, presence, a whole list of qualities, and sometimes those qualities aren't found in someone who fits the textual descriptions in the novel.That being said, it stretched credulity to cast a 44 year old actor to play a character that Austen describes as "a young man of five and twenty", who has only just been ordained a minister six months prior.

There are many negative stereotypes that society piles on to everyone, including middle aged men, but in this application it is the contrast between a middle aged Collins and the gaggle of teenage Bennet daughters that increases the "creep" level and pushes the audience even further into dislike for Mr. Collins. What better way to make his heartless and utilitarian proposal to Elizabeth even more distasteful to the audience? Where these same actions and words from a young man could be explained as awkwardness or naivete, perhaps even come off as pathetically endearing, an older man is warranted no such leeway.

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Cooper's portrayal of Collins is also loud and self ingratiating to the point where every person in the room simply wants to leave or force themselves to go deaf. We have become accustomed to "movie Collins" as the self-aggrandizing bore, but Austen's "novel Collins" is quite different. He is no attention seeker and his self congratulating comments revolve entirely around his fringe association with Lady Catherine de Bourge. In fact, he is described as being very grave and having excessively formal manners. Grave, formal people do not wave their monocles around a room while talking about how great they are.

I do not argue that Cooper played Mr. Collins badly. He just played a Mr. Collins that Austen would not have recognized.

Going on to the 1995 mini-series of Pride & Prejudice, we see the same casting choices made again. Mr. Collins is played by David Bamber, this time 41 years old. Bamber's portrayal of Collins is, in this author's opinion, the least likable of all the screen portrayals. (Meaning, the Collins character is unlikable, not Bamber's acting). In this version, Collins is an absolute clown. He grins, wide and toothy and at the most inappropriate times.

Pride & Prejudice (1995)

Pride & Prejudice (1995)

Pride & Prejudice (1995)He is physically clumsy and appears to be aware of it, as his comic self corrections and self-conscious looks clearly show. As with the 1940 version, the deficiencies of Bamber's Collins are only intensified in horror and inappropriateness by making him a man of middle age*. A young man with these same characteristic would probably garner a more sympathetic response from the viewing audience, and since—let us say it again—the audience is supposed to dislike Mr. Collins, this would explain the casting choice.

Pride & Prejudice (1995)He is physically clumsy and appears to be aware of it, as his comic self corrections and self-conscious looks clearly show. As with the 1940 version, the deficiencies of Bamber's Collins are only intensified in horror and inappropriateness by making him a man of middle age*. A young man with these same characteristic would probably garner a more sympathetic response from the viewing audience, and since—let us say it again—the audience is supposed to dislike Mr. Collins, this would explain the casting choice.

There is also rather a large dose of the effeminate in Bamber's portrayal, especially in the way Mr. Collins walks, waves to people, and at times downright simpers like a stage parody.

He encounters Lydia in the upstairs hallway wearing her undergarments (full dress coverings to us modern people), and reacts like a frightened rabbit (the old insulting stereotype of the gay man falling to pieces at the sight of female nudity).

He encounters Lydia in the upstairs hallway wearing her undergarments (full dress coverings to us modern people), and reacts like a frightened rabbit (the old insulting stereotype of the gay man falling to pieces at the sight of female nudity).

This, I will speak little on, but if movie makers are in the habit of using greater society's prejudices as tools to get the audience reactions they want, one could easily argue that this was also intentional. A homophobic audience will like an effeminate Mr. Collins even less. It was, remember, 1995. Twenty-one years later and many of us can easily forget what a different world 1995 was.

Finally, the 2005 version starring Tom Hollander is a vast improvement. Hollander is 38, still 13 years older than Austen's character, but the age is not emphasized as in the earlier movies. What is, unfortunately, emphasized to a rather shameful degree is Hollander's height.

Pride & Prejudice (2005)At 5'5", Hollander is shorter than practically every other character in the entire film! Camera angles seem intentionally designed to have him looking up at everyone, a supplicant, a "low man" attempting to mingle in a society that does not want him and where he is vastly out of his depth. If one needed a single image to encompass Collins's role in this film, it is that of Darcy looking down at him, both figuratively and literally, when he introduces himself at the Bingley's ball.

Pride & Prejudice (2005)At 5'5", Hollander is shorter than practically every other character in the entire film! Camera angles seem intentionally designed to have him looking up at everyone, a supplicant, a "low man" attempting to mingle in a society that does not want him and where he is vastly out of his depth. If one needed a single image to encompass Collins's role in this film, it is that of Darcy looking down at him, both figuratively and literally, when he introduces himself at the Bingley's ball.

In 1940, Mr. Collins is a lecherous, self aggrandizing snob. In 1995, he is an insensible clown with two left feet and a head-tilt smile that would make Monty Python proud. In 2005 he is no longer a clown, no longer loud and attention seeking, and no longer the creepy older man seeking to wed a young girl. He is just...pathetic.Quiet and "small" and so beneath the attention of an outlier like Elizabeth Bennet that it is almost laughable.

And this is why Hollander's portrayal is by the far the best.

I don't wish to turn this into a movie review, but Hollander's Collins is the closest thing to Austen's original. He is grave and very formal, and speaks with the solemn air of a clergyman always presiding over a funeral, but he is also terribly uncomfortable. Hollander read between the lines and saw what the movie fans never have, and what only the thoughtful readers have probably discerned:

Mr. Collins is not full of himself. He is not sure of his superiority or place.His insecurity explains why he pretends so fiercely to the contrary.

Hollander gave depth to a shallow character by presenting the novel idea (almost like a fan theory) that Collins is putting up a front. He is a 19th century victim of the 20th century "fake it till you make it" attitude. He just doesn't do it very well and Hollander let the inner discomfort show through, giving the audience occasional glimpses of a guy who is just lost in a world he wasn't raised in. He's a guy who thought he was doing a good thing by offering marriage to a young woman, his cousin, who has only her father's life between her and eventual genteel poverty. As another blogger out there in the internet-lands once wrote of Collins, "This is not a dick move."

Hollander gave depth to a shallow character by presenting the novel idea (almost like a fan theory) that Collins is putting up a front. He is a 19th century victim of the 20th century "fake it till you make it" attitude. He just doesn't do it very well and Hollander let the inner discomfort show through, giving the audience occasional glimpses of a guy who is just lost in a world he wasn't raised in. He's a guy who thought he was doing a good thing by offering marriage to a young woman, his cousin, who has only her father's life between her and eventual genteel poverty. As another blogger out there in the internet-lands once wrote of Collins, "This is not a dick move."

[More analysis to come in future posts. Poor Mr. Collins, Part 2 - "Not a Dick Move"]

Mr. Collins is not supposed to be liked. Readers and movie watchers alike are supposed to be empathizing with the heroine Elizabeth Bennet, and since her dislike of Mr. Collins is so extreme—far too extreme, in this author's opinion—movie makers seem to have gone to extra lengths to make certain the audience really, really dislikes Mr. Collins. They did this through the use of various negative male stereotypes such as age, height, presence, and even allusions to lack of masculinity. And since human beings are visual creatures, our popular impressions of Mr. Collins have been formed by the movies much more than they ever were by the book.

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Pride & Prejudice (1940)In the 1940 version starring Lawrence Olivier as Darcy, Mr. Collins is played by Melville Cooper. Cooper takes on the role at the age of 44, playing a tall, bombastic, attention seeking Collins. Cooper wore stage makeup during filming that was intentionally designed to make him look older than his 44 years. Now, one should never expect or demand precise casting in movies. Casting directors have to look for talent, availability, presence, a whole list of qualities, and sometimes those qualities aren't found in someone who fits the textual descriptions in the novel.That being said, it stretched credulity to cast a 44 year old actor to play a character that Austen describes as "a young man of five and twenty", who has only just been ordained a minister six months prior.

There are many negative stereotypes that society piles on to everyone, including middle aged men, but in this application it is the contrast between a middle aged Collins and the gaggle of teenage Bennet daughters that increases the "creep" level and pushes the audience even further into dislike for Mr. Collins. What better way to make his heartless and utilitarian proposal to Elizabeth even more distasteful to the audience? Where these same actions and words from a young man could be explained as awkwardness or naivete, perhaps even come off as pathetically endearing, an older man is warranted no such leeway.

Pride & Prejudice (1940)

Pride & Prejudice (1940)Cooper's portrayal of Collins is also loud and self ingratiating to the point where every person in the room simply wants to leave or force themselves to go deaf. We have become accustomed to "movie Collins" as the self-aggrandizing bore, but Austen's "novel Collins" is quite different. He is no attention seeker and his self congratulating comments revolve entirely around his fringe association with Lady Catherine de Bourge. In fact, he is described as being very grave and having excessively formal manners. Grave, formal people do not wave their monocles around a room while talking about how great they are.

I do not argue that Cooper played Mr. Collins badly. He just played a Mr. Collins that Austen would not have recognized.

Going on to the 1995 mini-series of Pride & Prejudice, we see the same casting choices made again. Mr. Collins is played by David Bamber, this time 41 years old. Bamber's portrayal of Collins is, in this author's opinion, the least likable of all the screen portrayals. (Meaning, the Collins character is unlikable, not Bamber's acting). In this version, Collins is an absolute clown. He grins, wide and toothy and at the most inappropriate times.

Pride & Prejudice (1995)

Pride & Prejudice (1995) Pride & Prejudice (1995)He is physically clumsy and appears to be aware of it, as his comic self corrections and self-conscious looks clearly show. As with the 1940 version, the deficiencies of Bamber's Collins are only intensified in horror and inappropriateness by making him a man of middle age*. A young man with these same characteristic would probably garner a more sympathetic response from the viewing audience, and since—let us say it again—the audience is supposed to dislike Mr. Collins, this would explain the casting choice.

Pride & Prejudice (1995)He is physically clumsy and appears to be aware of it, as his comic self corrections and self-conscious looks clearly show. As with the 1940 version, the deficiencies of Bamber's Collins are only intensified in horror and inappropriateness by making him a man of middle age*. A young man with these same characteristic would probably garner a more sympathetic response from the viewing audience, and since—let us say it again—the audience is supposed to dislike Mr. Collins, this would explain the casting choice. There is also rather a large dose of the effeminate in Bamber's portrayal, especially in the way Mr. Collins walks, waves to people, and at times downright simpers like a stage parody.

He encounters Lydia in the upstairs hallway wearing her undergarments (full dress coverings to us modern people), and reacts like a frightened rabbit (the old insulting stereotype of the gay man falling to pieces at the sight of female nudity).

He encounters Lydia in the upstairs hallway wearing her undergarments (full dress coverings to us modern people), and reacts like a frightened rabbit (the old insulting stereotype of the gay man falling to pieces at the sight of female nudity).This, I will speak little on, but if movie makers are in the habit of using greater society's prejudices as tools to get the audience reactions they want, one could easily argue that this was also intentional. A homophobic audience will like an effeminate Mr. Collins even less. It was, remember, 1995. Twenty-one years later and many of us can easily forget what a different world 1995 was.

Finally, the 2005 version starring Tom Hollander is a vast improvement. Hollander is 38, still 13 years older than Austen's character, but the age is not emphasized as in the earlier movies. What is, unfortunately, emphasized to a rather shameful degree is Hollander's height.

Pride & Prejudice (2005)At 5'5", Hollander is shorter than practically every other character in the entire film! Camera angles seem intentionally designed to have him looking up at everyone, a supplicant, a "low man" attempting to mingle in a society that does not want him and where he is vastly out of his depth. If one needed a single image to encompass Collins's role in this film, it is that of Darcy looking down at him, both figuratively and literally, when he introduces himself at the Bingley's ball.

Pride & Prejudice (2005)At 5'5", Hollander is shorter than practically every other character in the entire film! Camera angles seem intentionally designed to have him looking up at everyone, a supplicant, a "low man" attempting to mingle in a society that does not want him and where he is vastly out of his depth. If one needed a single image to encompass Collins's role in this film, it is that of Darcy looking down at him, both figuratively and literally, when he introduces himself at the Bingley's ball.

In 1940, Mr. Collins is a lecherous, self aggrandizing snob. In 1995, he is an insensible clown with two left feet and a head-tilt smile that would make Monty Python proud. In 2005 he is no longer a clown, no longer loud and attention seeking, and no longer the creepy older man seeking to wed a young girl. He is just...pathetic.Quiet and "small" and so beneath the attention of an outlier like Elizabeth Bennet that it is almost laughable.

And this is why Hollander's portrayal is by the far the best.

I don't wish to turn this into a movie review, but Hollander's Collins is the closest thing to Austen's original. He is grave and very formal, and speaks with the solemn air of a clergyman always presiding over a funeral, but he is also terribly uncomfortable. Hollander read between the lines and saw what the movie fans never have, and what only the thoughtful readers have probably discerned:

Mr. Collins is not full of himself. He is not sure of his superiority or place.His insecurity explains why he pretends so fiercely to the contrary.

Hollander gave depth to a shallow character by presenting the novel idea (almost like a fan theory) that Collins is putting up a front. He is a 19th century victim of the 20th century "fake it till you make it" attitude. He just doesn't do it very well and Hollander let the inner discomfort show through, giving the audience occasional glimpses of a guy who is just lost in a world he wasn't raised in. He's a guy who thought he was doing a good thing by offering marriage to a young woman, his cousin, who has only her father's life between her and eventual genteel poverty. As another blogger out there in the internet-lands once wrote of Collins, "This is not a dick move."

Hollander gave depth to a shallow character by presenting the novel idea (almost like a fan theory) that Collins is putting up a front. He is a 19th century victim of the 20th century "fake it till you make it" attitude. He just doesn't do it very well and Hollander let the inner discomfort show through, giving the audience occasional glimpses of a guy who is just lost in a world he wasn't raised in. He's a guy who thought he was doing a good thing by offering marriage to a young woman, his cousin, who has only her father's life between her and eventual genteel poverty. As another blogger out there in the internet-lands once wrote of Collins, "This is not a dick move."[More analysis to come in future posts. Poor Mr. Collins, Part 2 - "Not a Dick Move"]

Published on April 05, 2016 17:43

January 19, 2016

Jackson & Angelo: Teaching the Regency Gentleman how to Fight.

If you enjoy reading Regency romances, you've probably heard of Henry Angelo, and have definitely hear of John "Gentleman" Jackson. These men operated exclusive training academies for fencing (swordsmanship) and boxing respectively. Jackson's, especially, is a commonly used setting in novels. It is part of the 'template', so to speak; the short list of places and names that seem to typify and close in the world of the upper class gentleman.

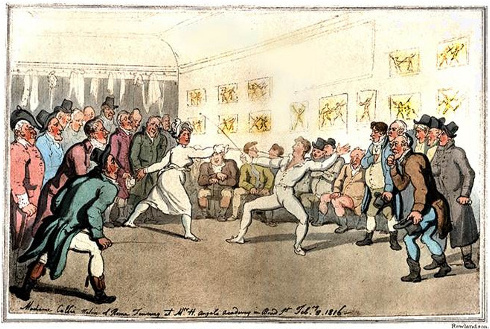

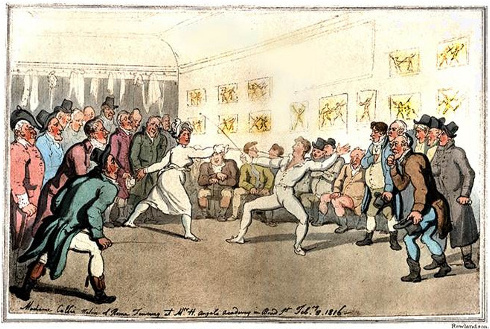

Roman fencer, Madam Collie, showing her skill to Mr. Henry Angelo in his room on Old Bond Street, 1816.John "Gentleman" Jackson & Henry Angelo

Roman fencer, Madam Collie, showing her skill to Mr. Henry Angelo in his room on Old Bond Street, 1816.John "Gentleman" Jackson & Henry Angelo

I will dispense with the biographies of the famous English boxer and the Italian who helped create the sport of fencing because they aren't important here. What is of far greater interest, to writers especially, is the boxing academy Jackson operated; a famous gymnasium style haunt where rich and well connected men learned to box, maintained their fashionable figures, and socialized. It was the country club before country clubs.

Despite being a setting in countless novels, we know virtually nothing about the place itself. Here is what we don't know:

How big was it? How many floors? Was it like a modern gym with dressing rooms, or did gentlemen just remove their coats and spar in their street clothes? (some of this further down)How did one become a member? How much did it cost to use the facilities or undertake training? How often were dues collected? Quarterly? Yearly?I have scoured the internet and the few other research tools available to me (oh, how I miss my college days when I had university access to everything!), and I can find no information at all about the floor plan or overall layout of the building.

[In One Glimpse (#2, Indulgence), Samuel Shaw leaves the main room of Jackson's and goes to the dressing rooms to change his clothes before leaving. There is no historical evidence of such rooms, but I simply can't imagine there weren't adequate facilities for patrons sweating in a gymnasium.]

These questions may sound trivial, but writers require the trivia. A gentleman hero who has fallen on hard financial times would certainly care about the cost and frequency of membership dues, as would the writer creating him. How is our poor hero to keep up appearances in the cut-throat world of the ton if he can no longer afford his club memberships!? It would also stretch credulity to write a suddenly impoverished character who doesn't seem to suffer any changes in his daily schedule. That's just not reality.

[In One Kiss (#3, Indulgence), Julian pays his fees at Jackson's in order to continue going there and keep up appearances, despite his serious money troubles. In the book, I claim this payment to be quarterly, but there is no real evidence this was the case. The lack of information leaves me free to fill in the blanks as I wish, lol]

But, alas, there are no answers to these questions. Such minutia was rarely thrilling and thus not often mentioned in memoirs or surviving letters. The two memoirs written by Henry Angelo are hardly historically useful. They are--sorry, Henry--mostly name dropping anecdotes designed to show how well heeled and fashionable he was. So, unless some new documents come to light or some out of print memoir gets scanned into the Google Books mountain, there are no answers to such detailed questions.

But, here is what we do know:

1) The school was located at 13 Old Bond Street.

The building currently occupying the space of 13 Old Bond was built at the turn of the 20th century and today houses a Jaeger-LeCoultre Swiss watch boutique. There is no remaining sign of the 18th century structure, nor can I find any drawings or pictures relating to what stood there before the latest building. Even the famous London Street Views of Mr. John Tallis do not touch number 13 Old Bond (damn it!).

But, considering the row style structure of the area at the time, it is most likely the place was narrow, long, tall, and nondescript. Bird's eye maps of the time period confirm this.

2) Jackson's boxing saloon and Angelo's School of Fencing were the same place.

For many years until 1817, both clubs shared the same rooms at 13 Old Bond Street. The actual name of the place was The Bond Street School of Arms. Angelo and Jackson had a professional arrangement by which they had use of the premises on alternating days. Both Jackson and Angelo encouraged their students to study both disciplines in alternation like this. Illustrations of the rooms (see below) show boxing and fencing equipment in the same space, and this is verified by Lord Byron, who wrote in his memoirs of taking fencing lessons in their shared rooms, "...I was a pupil of [Angelo] and of Mr. Jackson, who had the use of his rooms in Albany on the alternate days...."1

It gets muddy when Byron refers to Angelo's rooms in Albany. The Albany was, and is, an exclusive apartment building in Piccadilly. Either Angelo had instruction spaces in more than one place at the same time, or these references to the Albany are actually referring to 13 Old Bond Street, as that address is barely a 3 minute walk from the Albany mansion. I just can't be sure, but it makes more sense to me that Angelo would be giving fencing lessons in a public space on Bond street rather than in an exclusive private residence (where one would assume people are trying to sleep!). Also, it was fashionable to refer to the Albany simply as 'Albany', as if the place and its immediate surroundings were their own town or country estate.

3) The rooms were very simple.

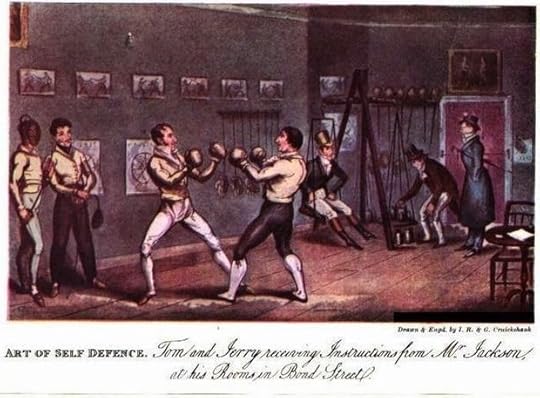

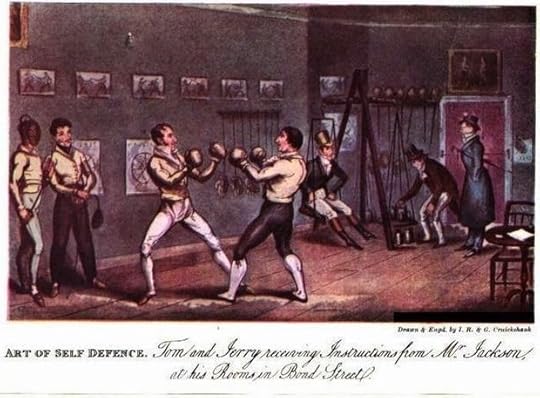

Various prints and artworks, such as those from Life in London, show a rather simplistic interior, a large room that could quickly and easily be converted to the necessary purpose. Most public spaces in the 18th century and through the regency were built on the 'any purpose' model like this.

Above we have a print showing the main room of the School of Arms. Jackson is giving a boxing lesson while the man standing at the far left is holding a foil and wearing a fencer's protective mask. As you can see, the room is rather home like. One could imagine it having been a private residence or easily turning into one. At the far right is even a little table and chair where someone might have been writing a letter. [In the days before phones or even the telegraph, it was common for ink and paper to be made available in public places for someone to jot off a note, most likely to be hand delivered by a servant. Can you imagine the local Starbucks today just having some paper and pens lying around for customer use? 'Hey, need to write a letter? Just next to the cream and sugar.']

4) The school was a social club as much as a training studio.

In the above image, the four men on the left are wearing matching buff jackets. These were the uniform, so to speak, of those engaging in training, much likely the quilted tunics of fencers. The three men on the right are still wearing their coats and hat, one even still carrying his cane. It seems they are merely there to observe and chat. Men routinely visited the school just to watch boxing and fencing matches, whether they took instruction or not. Though, gaining entry was most likely still on a "we know you" basis, not open to just anyone off the street.

This image, showing a gentlemen's fencing match, has the same atmosphere; some of the men are wearing fencing tunics and taking instruction, while others are simply there for the show.

[Allow me to take a moment and gush over just how much I love this print. It is my visual muse for Julian Garrott and one of my favorite scenes in One Kiss, which I am still writing. Julian an expert swordsman =D]

In the end, the school of arms Jackson and Angelo ran was just one place, and not even the only place of its kind. There were other instructors and other sporting clubs, but it was a mark of rank and prestige to get instruction for the two greatest. To an historian, it's always disappointing when culturally important places and people end up coming to us with so little information, but we take what we can. And, let's be honest, the holes allow the fictional writer a bit more freedom of movement ;)

[Note: If you see something inaccurate in this essay or have more information about the topics discussed, please leave a comment or sent an email =) I am always looking for more and better research materials]

1. Byron, George Gordon, Baron. The Life, Letters, and Journals of Lord Byron, etc. Ed. Sir Walter Scott, Thomas Moore, and others. London: John Murray, 1860. p. 704.

Roman fencer, Madam Collie, showing her skill to Mr. Henry Angelo in his room on Old Bond Street, 1816.John "Gentleman" Jackson & Henry Angelo

Roman fencer, Madam Collie, showing her skill to Mr. Henry Angelo in his room on Old Bond Street, 1816.John "Gentleman" Jackson & Henry AngeloI will dispense with the biographies of the famous English boxer and the Italian who helped create the sport of fencing because they aren't important here. What is of far greater interest, to writers especially, is the boxing academy Jackson operated; a famous gymnasium style haunt where rich and well connected men learned to box, maintained their fashionable figures, and socialized. It was the country club before country clubs.

Despite being a setting in countless novels, we know virtually nothing about the place itself. Here is what we don't know:

How big was it? How many floors? Was it like a modern gym with dressing rooms, or did gentlemen just remove their coats and spar in their street clothes? (some of this further down)How did one become a member? How much did it cost to use the facilities or undertake training? How often were dues collected? Quarterly? Yearly?I have scoured the internet and the few other research tools available to me (oh, how I miss my college days when I had university access to everything!), and I can find no information at all about the floor plan or overall layout of the building.

[In One Glimpse (#2, Indulgence), Samuel Shaw leaves the main room of Jackson's and goes to the dressing rooms to change his clothes before leaving. There is no historical evidence of such rooms, but I simply can't imagine there weren't adequate facilities for patrons sweating in a gymnasium.]

These questions may sound trivial, but writers require the trivia. A gentleman hero who has fallen on hard financial times would certainly care about the cost and frequency of membership dues, as would the writer creating him. How is our poor hero to keep up appearances in the cut-throat world of the ton if he can no longer afford his club memberships!? It would also stretch credulity to write a suddenly impoverished character who doesn't seem to suffer any changes in his daily schedule. That's just not reality.

[In One Kiss (#3, Indulgence), Julian pays his fees at Jackson's in order to continue going there and keep up appearances, despite his serious money troubles. In the book, I claim this payment to be quarterly, but there is no real evidence this was the case. The lack of information leaves me free to fill in the blanks as I wish, lol]

But, alas, there are no answers to these questions. Such minutia was rarely thrilling and thus not often mentioned in memoirs or surviving letters. The two memoirs written by Henry Angelo are hardly historically useful. They are--sorry, Henry--mostly name dropping anecdotes designed to show how well heeled and fashionable he was. So, unless some new documents come to light or some out of print memoir gets scanned into the Google Books mountain, there are no answers to such detailed questions.

But, here is what we do know:

1) The school was located at 13 Old Bond Street.

The building currently occupying the space of 13 Old Bond was built at the turn of the 20th century and today houses a Jaeger-LeCoultre Swiss watch boutique. There is no remaining sign of the 18th century structure, nor can I find any drawings or pictures relating to what stood there before the latest building. Even the famous London Street Views of Mr. John Tallis do not touch number 13 Old Bond (damn it!).

But, considering the row style structure of the area at the time, it is most likely the place was narrow, long, tall, and nondescript. Bird's eye maps of the time period confirm this.

2) Jackson's boxing saloon and Angelo's School of Fencing were the same place.

For many years until 1817, both clubs shared the same rooms at 13 Old Bond Street. The actual name of the place was The Bond Street School of Arms. Angelo and Jackson had a professional arrangement by which they had use of the premises on alternating days. Both Jackson and Angelo encouraged their students to study both disciplines in alternation like this. Illustrations of the rooms (see below) show boxing and fencing equipment in the same space, and this is verified by Lord Byron, who wrote in his memoirs of taking fencing lessons in their shared rooms, "...I was a pupil of [Angelo] and of Mr. Jackson, who had the use of his rooms in Albany on the alternate days...."1

It gets muddy when Byron refers to Angelo's rooms in Albany. The Albany was, and is, an exclusive apartment building in Piccadilly. Either Angelo had instruction spaces in more than one place at the same time, or these references to the Albany are actually referring to 13 Old Bond Street, as that address is barely a 3 minute walk from the Albany mansion. I just can't be sure, but it makes more sense to me that Angelo would be giving fencing lessons in a public space on Bond street rather than in an exclusive private residence (where one would assume people are trying to sleep!). Also, it was fashionable to refer to the Albany simply as 'Albany', as if the place and its immediate surroundings were their own town or country estate.

3) The rooms were very simple.

Various prints and artworks, such as those from Life in London, show a rather simplistic interior, a large room that could quickly and easily be converted to the necessary purpose. Most public spaces in the 18th century and through the regency were built on the 'any purpose' model like this.

Above we have a print showing the main room of the School of Arms. Jackson is giving a boxing lesson while the man standing at the far left is holding a foil and wearing a fencer's protective mask. As you can see, the room is rather home like. One could imagine it having been a private residence or easily turning into one. At the far right is even a little table and chair where someone might have been writing a letter. [In the days before phones or even the telegraph, it was common for ink and paper to be made available in public places for someone to jot off a note, most likely to be hand delivered by a servant. Can you imagine the local Starbucks today just having some paper and pens lying around for customer use? 'Hey, need to write a letter? Just next to the cream and sugar.']

4) The school was a social club as much as a training studio.

In the above image, the four men on the left are wearing matching buff jackets. These were the uniform, so to speak, of those engaging in training, much likely the quilted tunics of fencers. The three men on the right are still wearing their coats and hat, one even still carrying his cane. It seems they are merely there to observe and chat. Men routinely visited the school just to watch boxing and fencing matches, whether they took instruction or not. Though, gaining entry was most likely still on a "we know you" basis, not open to just anyone off the street.

This image, showing a gentlemen's fencing match, has the same atmosphere; some of the men are wearing fencing tunics and taking instruction, while others are simply there for the show.

[Allow me to take a moment and gush over just how much I love this print. It is my visual muse for Julian Garrott and one of my favorite scenes in One Kiss, which I am still writing. Julian an expert swordsman =D]

In the end, the school of arms Jackson and Angelo ran was just one place, and not even the only place of its kind. There were other instructors and other sporting clubs, but it was a mark of rank and prestige to get instruction for the two greatest. To an historian, it's always disappointing when culturally important places and people end up coming to us with so little information, but we take what we can. And, let's be honest, the holes allow the fictional writer a bit more freedom of movement ;)

[Note: If you see something inaccurate in this essay or have more information about the topics discussed, please leave a comment or sent an email =) I am always looking for more and better research materials]

1. Byron, George Gordon, Baron. The Life, Letters, and Journals of Lord Byron, etc. Ed. Sir Walter Scott, Thomas Moore, and others. London: John Murray, 1860. p. 704.

Published on January 19, 2016 20:33

December 24, 2015

2015 Member's Choice Awards

It's an amazing honor to have One Glimpse nominated in this year's awards for Best Historical.

I encourage everyone to participate in the awards and show support for your favorite works this year. Also, the nominations are a gateway to some amazing novels and new authors. Go have a look at the lists =)

One Glimpse (Indulgence #2) - Amazon, LooseId, B&N, , etc.

One Glimpse (Indulgence #2) - Amazon, LooseId, B&N, , etc.

"For years, Sir Samuel Shaw has secretly lusted after the handsome and popular Lord John Darnish, a man known for his good humor, expert riding prowess, and very female mistress. Certain that John is an unattainable fantasy, Sam is shaken when an accidental discovery reveals John might not be as unattainable as he once thought. But what is possible is not always likely, and Sam finds himself trapped between keeping a friend and risking everything for the unlikely hope of something more.

John is terrorstruck when his drunken mistake threatens to shatter the double life he has worked so hard to maintain. His terror soon turns to hope when he finds himself drawn to Sam, who he is sure does not share his interest in men. But subtle things cause him to second guess and fear that his hopes are making him see what he wants to see."

I encourage everyone to participate in the awards and show support for your favorite works this year. Also, the nominations are a gateway to some amazing novels and new authors. Go have a look at the lists =)

One Glimpse (Indulgence #2) - Amazon, LooseId, B&N, , etc.

One Glimpse (Indulgence #2) - Amazon, LooseId, B&N, , etc."For years, Sir Samuel Shaw has secretly lusted after the handsome and popular Lord John Darnish, a man known for his good humor, expert riding prowess, and very female mistress. Certain that John is an unattainable fantasy, Sam is shaken when an accidental discovery reveals John might not be as unattainable as he once thought. But what is possible is not always likely, and Sam finds himself trapped between keeping a friend and risking everything for the unlikely hope of something more.

John is terrorstruck when his drunken mistake threatens to shatter the double life he has worked so hard to maintain. His terror soon turns to hope when he finds himself drawn to Sam, who he is sure does not share his interest in men. But subtle things cause him to second guess and fear that his hopes are making him see what he wants to see."

Published on December 24, 2015 14:35

November 25, 2015

The Regency Upper Class, and 'the right kind' of rich.

Cit! Mushroom! Counter hopper!

If you cut your teeth reading old regency romances like I did, you're probably familiar these terms. For those who did not, they represent a very particular form of class discrimination that was common in the upper classes of the 19th century and earlier. Gaining entry to the upper class wasn't a task one could accomplish simply by being rich. You had to be the right kind of rich, and those who made their money from the labor of their hands or sale of their goods were not welcome. Or, as so often happened when a titled person was in need of money, they were begrudgingly welcomed.

Regardless of the slurs being used, they all boiled down to the same upper class fear of the 'other' gaining entry to a very exclusive club. If someone could get in by wealth alone, that opened the door to a near endless list of potential gatecrashers.

Regardless of the slurs being used, they all boiled down to the same upper class fear of the 'other' gaining entry to a very exclusive club. If someone could get in by wealth alone, that opened the door to a near endless list of potential gatecrashers.

But, if it wasn't acceptable to make money through trade or work, how on Earth did the upper class maintain any kind of wealth? Well, a man had limited options if he wanted to maintain his reputation and still be called a gentleman. Our modern ears hear the word gentleman and think polite, kind, well mannered; the term had a much more specific meaning, once upon a time. A gentleman was, first and foremost, idle. If you worked, you were no gentleman.

The Land Lord: The most approved form of wealth for the upper class was land ownership and rents. As the most idle form of income imaginable, this is the very definition of 'no work'. Unfortunately, it could also be the most unstable. A bad turn in the weather could destroy crops, thus impoverishing the tenants and making them unable to pay their rent. Even the rich lord of the manor can't bleed a stone. The Percents: Making money from money. The rich would place the vast majority of their capital into bank account that issued returns as a percent, essentially an annuity. They would live off the annuity alone, not spending the actual principal amount. At least, this was what the smart ones did. More than one upper class family was ruined when the patriarch outspent his income and was forced to chip away the principal to pay debts. In Jane Austen's novel, you often hear someone's income described as an annuity, "He has fifty thousand pounds in the six percents." Etc.Dowries (marrying money):It was easier for a woman to rise in society than a man, since women essentially left their families and joined new ones upon marriage. Because of this, a broke man with maybe a title or grand familial connections could marry a rich girl from one of those "vulgar" merchant families and prop up his dwindling wealth. Pointing out the hypocrisy of disdaining merchant money while taking it in the form of a dowry would be pointless. The regency upper classes were connoisseurs of hypocrisy. Military & Clergy: These were the only 'professions' deemed acceptable for the sons of gentleman, jobs they could hold and still keep their status. If you were a second or third son with no inheritance coming to you, this was your most likely path (unless your family name was grand enough to attract one of those rich merchant class girls). Still, it should be noted that if a man relied entirely on his military or clerical salary to live, he fell significantly in stature. Wealth was still important, after all. Other professions such as the law and government service were acceptable, but they placed a man at the fringes, and unless he was able to marry up it was likely his children would drop down into the merchant class and float away from the top.

Viewed with the historical perspective.

Viewed with the historical perspective.

The best way to read historical fiction is through the lens of the time period itself. If you step into a regency romance with 21st century expectations, you are likely to be disappointed. It is easy for us to sneer at the money troubles of a gentleman and say, "Get a job!" when we consider the hundreds of thousands of working class people below that gentleman. We feel uncomfortable having sympathy for a character who, by every comparison to our modern society, would have been so privileged and coddled that it almost boggles the mind. We must struggle to understand a long gone world in which people were born into structures and never taught how to live outside of them. Men and women raised with narrow educations and abilities, coupled with an ingrained fear and shame of doing anything outside that structure. Reputation was everything, to a degree that we today would be hard pressed to understand. It would take a incredibly strong person to give up their friends, society, to risk embarrassing their family and becoming and object of derision, all for the sake of stepping outside the structure for money. This is where genteel poverty comes from. The social penalties for stepping outside the structure, for working, were such that some families chose to live hand to mouth on the scraps of their dwindling wealth rather than work.

If you cut your teeth reading old regency romances like I did, you're probably familiar these terms. For those who did not, they represent a very particular form of class discrimination that was common in the upper classes of the 19th century and earlier. Gaining entry to the upper class wasn't a task one could accomplish simply by being rich. You had to be the right kind of rich, and those who made their money from the labor of their hands or sale of their goods were not welcome. Or, as so often happened when a titled person was in need of money, they were begrudgingly welcomed.

Regardless of the slurs being used, they all boiled down to the same upper class fear of the 'other' gaining entry to a very exclusive club. If someone could get in by wealth alone, that opened the door to a near endless list of potential gatecrashers.

Regardless of the slurs being used, they all boiled down to the same upper class fear of the 'other' gaining entry to a very exclusive club. If someone could get in by wealth alone, that opened the door to a near endless list of potential gatecrashers. But, if it wasn't acceptable to make money through trade or work, how on Earth did the upper class maintain any kind of wealth? Well, a man had limited options if he wanted to maintain his reputation and still be called a gentleman. Our modern ears hear the word gentleman and think polite, kind, well mannered; the term had a much more specific meaning, once upon a time. A gentleman was, first and foremost, idle. If you worked, you were no gentleman.

The Land Lord: The most approved form of wealth for the upper class was land ownership and rents. As the most idle form of income imaginable, this is the very definition of 'no work'. Unfortunately, it could also be the most unstable. A bad turn in the weather could destroy crops, thus impoverishing the tenants and making them unable to pay their rent. Even the rich lord of the manor can't bleed a stone. The Percents: Making money from money. The rich would place the vast majority of their capital into bank account that issued returns as a percent, essentially an annuity. They would live off the annuity alone, not spending the actual principal amount. At least, this was what the smart ones did. More than one upper class family was ruined when the patriarch outspent his income and was forced to chip away the principal to pay debts. In Jane Austen's novel, you often hear someone's income described as an annuity, "He has fifty thousand pounds in the six percents." Etc.Dowries (marrying money):It was easier for a woman to rise in society than a man, since women essentially left their families and joined new ones upon marriage. Because of this, a broke man with maybe a title or grand familial connections could marry a rich girl from one of those "vulgar" merchant families and prop up his dwindling wealth. Pointing out the hypocrisy of disdaining merchant money while taking it in the form of a dowry would be pointless. The regency upper classes were connoisseurs of hypocrisy. Military & Clergy: These were the only 'professions' deemed acceptable for the sons of gentleman, jobs they could hold and still keep their status. If you were a second or third son with no inheritance coming to you, this was your most likely path (unless your family name was grand enough to attract one of those rich merchant class girls). Still, it should be noted that if a man relied entirely on his military or clerical salary to live, he fell significantly in stature. Wealth was still important, after all. Other professions such as the law and government service were acceptable, but they placed a man at the fringes, and unless he was able to marry up it was likely his children would drop down into the merchant class and float away from the top.

Viewed with the historical perspective.

Viewed with the historical perspective.The best way to read historical fiction is through the lens of the time period itself. If you step into a regency romance with 21st century expectations, you are likely to be disappointed. It is easy for us to sneer at the money troubles of a gentleman and say, "Get a job!" when we consider the hundreds of thousands of working class people below that gentleman. We feel uncomfortable having sympathy for a character who, by every comparison to our modern society, would have been so privileged and coddled that it almost boggles the mind. We must struggle to understand a long gone world in which people were born into structures and never taught how to live outside of them. Men and women raised with narrow educations and abilities, coupled with an ingrained fear and shame of doing anything outside that structure. Reputation was everything, to a degree that we today would be hard pressed to understand. It would take a incredibly strong person to give up their friends, society, to risk embarrassing their family and becoming and object of derision, all for the sake of stepping outside the structure for money. This is where genteel poverty comes from. The social penalties for stepping outside the structure, for working, were such that some families chose to live hand to mouth on the scraps of their dwindling wealth rather than work.

Published on November 25, 2015 23:37

November 16, 2015

5 Stars from Pinkerbelle!

I wanted to thank Pinkerbelle Rex (what a name!) for the amazing review of One Indulgence. Writing is not my first job and I doubt I will ever be able to make it my only job, so it truly is the reviews that "pay" me. Thanks for the wealth, Pink ;) LOL

I do believe this review is also at Rainbow Book Reviews

I do believe this review is also at Rainbow Book Reviews

Published on November 16, 2015 11:16

October 24, 2015

A "Snippet" From One Glimpse (Indulgence, Book 2)

Published on October 24, 2015 14:37

October 22, 2015

An Utterly Ridiculous Poem I wrote on the back of a piece of junk mail.

Romance will always be my labor of love, but sometimes you just want to write some nonsense, especially while you're waiting for food in a restaurant and going through all the junk paper in the bottom of your bag. Here is something silly, shallow, and utterly pointless...

...and written in the

A

BB

A

C

rhyme scheme, LOL ;)

...and written in the

A

BB

A

C

rhyme scheme, LOL ;)

Published on October 22, 2015 14:27

October 20, 2015

One Glimpse is now LIVE!

I wasn't expected One Glimpse (Indulgence #2) to be out until the 27th, but I learned that it hit Loose-Id.com tonight. So excited! It's been more than a year since One Indulgence was released, and so many personal circumstances forced me to do other things when I would have liked to be writing instead. Now that many of those things have been put to rest, I can get back to what I love. One Glimpse is out and I have already started work on Indulgence #3, tentatively titled One Kiss.

Happy reading, everyone! And, pssst! Be forewarned, this is a long one. 119K words. ;)

Now Available on Loose Id (other sellers too in the next week or so)

Happy reading, everyone! And, pssst! Be forewarned, this is a long one. 119K words. ;)

Now Available on Loose Id (other sellers too in the next week or so)

Published on October 20, 2015 00:36