Ying Chang Compestine's Blog

July 23, 2024

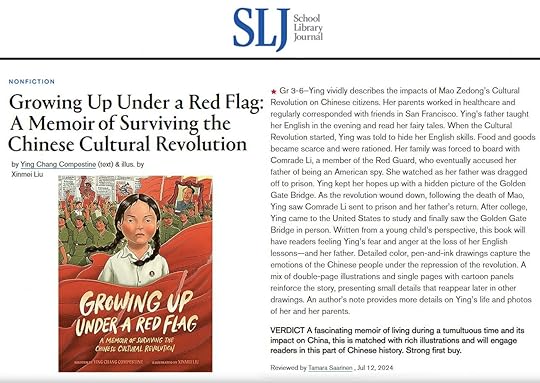

School Library Journal star-reviews Growing Up Under a Red Flag!

Exciting news! Just as we celebrate the summer literary season and reflect on current global political shifts, I've now received not one, not two, but THREE different "starred reviews" for my new illustrated memoir, Growing Up Under a Red Flag! Thank you so much School Library Journal, for your high praise, and thank you all for supporting this book during this politically significant time.

★"A fascinating memoir of living during a tumultuous time...matched with rich illustrations and will engage readers...Strong first buy."

-Tamara Saarinen, School Library Journal

Read the full review here: https://tinyurl.com/4z8z3meu

★"A fascinating memoir of living during a tumultuous time...matched with rich illustrations and will engage readers...Strong first buy."

-Tamara Saarinen, School Library Journal

Read the full review here: https://tinyurl.com/4z8z3meu

Published on July 23, 2024 12:27

July 18, 2024

Bay Area News Group features Ying and Growing Up Under a Red Flag in new interview!

I am thrilled that my new memoir, "Growing Up Under a Red Flag," is featured in this week's The Mercury News, East Bay Times, and the Marin Independent Journal.

Thanks to Martha Ross for the thoughtful and detailed coverage. Your insight in capturing the essence of my childhood growing up under Mao's reign is profound. Thank you all for sharing this important story with your readership.

Read the full article here: https://tinyurl.com/mrywn6w3

Thanks to Martha Ross for the thoughtful and detailed coverage. Your insight in capturing the essence of my childhood growing up under Mao's reign is profound. Thank you all for sharing this important story with your readership.

Read the full article here: https://tinyurl.com/mrywn6w3

Published on July 18, 2024 00:23

May 21, 2024

Kansas Public Radio Interview on 'Ra Pu Zel and the Stinky Tofu'

Thank you so much, Dan Skinner, for the wonderful interviews on Kansas Public Radio and for giving me the chance to showcase my resilient princess, Ra Pu Zel!

Check out the interview here: https://tinyurl.com/33jfcr5p

Check out the interview here: https://tinyurl.com/33jfcr5p

Published on May 21, 2024 13:56

November 17, 2022

Morning Sun and I made front-page of SF Chronicle Datebook!

Hello Everyone,

I'm so thrilled to share that Morning Sun in Wuhan was featured on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle Datebook!

I hope you will enjoy reading the article!

_____________________________________________

Bay Area chef/author Compestine turns COVID fears into lesson about compassion

Susan Faust November 8, 2022

Updated: November 9, 2022, 6:01 pm

Wuhan is not just the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s what East Bay author Ying Chang Compestine wants to show in “Morning Sun in Wuhan,” a multifaceted novel set at the start of the outbreak in early 2020 that reads like a love letter to her beloved but beleaguered birthplace.

The story centers on 13-year-old Mei as she copes with grief, plus COVID-induced fears and isolation. Her mother recently died of an accident, and her father has 24/7 duties as a respiratory doctor at Yangtze Hospital. With the deepening crisis, Mei is left on her own to play a computer cooking game and prepare food, at first, mostly for herself.

Thus, slipped into Mei’s gripping, day-by-day, monthlong account are passages of WeChat conversations and 10 easy-to-make recipes. (I tried out the lettuce cups, kung pao beef and hot dry noodles. Delicious!) Not surprisingly, Mei loves to cook — after all, Compestine is a TV chef, food consultant and cookbook author.

A child of the Cultural Revolution, Compestine emerged from its brutality and deprivation to joyously celebrate Chinese culture and cuisine in her 17 books for children, all published in the U.S. (Three more out this fall.) “Morning Sun in Wuhan” is no exception. But intertwined are other goals: to encourage girl power, counter racism, honor selflessness and extol community spirit.

Nearly three years ago, Compestine was set for a trip to Wuhan when her best friend in China called about a new virus. “Don’t worry, it’s not transmitted human to human,” Compestine recalled her friend telling her. Then Compestine remembered her mother’s advice: “Always listen to what is not being said. … You grow up in the Cultural Revolution … you have to survive.”

That’s when Compestine canceled her trip. Two weeks later, a quarantine locked down the city.

The situation was dire — a mysterious illness, overrun hospitals, not enough medical equipment or protective gear, no known treatment, food shortages, bodies piling up. Compestine found herself going crazy with worry for her family and friends. Far from the chaos, she said she cooked constantly and stayed up late to keep an eye on the stream of coronavirus updates.

“I watched all the news. It was just getting darker and darker, and I was just devastated,” she told The Chronicle during a recent video call from her home in Lafayette.

Desperate to know what was happening, Compestine relied on information from Chinese American friends, phone calls to her brother in Wuhan, TV news reports and blogs, some quickly blocked by the sensitive Chinese government. One day, still during the height of the pandemic, Compestine read about a group of young volunteers cooking for frontline workers.

“That’s when I saw that I have to write about this,” she said. “You know, this is goodness in the darkest time. I spent a lot of nights thinking about what I would do. … I probably would find a way to help too.”

And that is just what Mei does in the book. She distributes groceries in her apartment compound and enlists other children to work in an emergency kitchen to feed the hungry. Her story emphasizes how the people of Wuhan came together to share and survive.

Video clips of actual events in Wuhan are the basis for harrowing scenes in the book, Compestine said, such as a hospital nurse besieged by patients and the frantic girl chasing after an ambulance carrying away her dead mother. “It’s like a hell, like the end of the world,” the author said of seeing those scenes. “It just made my heart break.”

Photos from the time provided more on-the-ground detail. For example, Compestine could see how, without approved protective equipment, people had to improvise, turning plastic water jugs into helmets, and bras and grapefruit peels into masks.

After her acclaimed first novel, 2007’s “Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party,” Compestine had no intention of writing another middle-grade novel. That fictionalized memoir about growing up during the Cultural Revolution dredged up deep pain from her past. Her parents, both doctors, were denounced as enemies of the state. She was ostracized at school and lonely. But, the COVID crisis in Wuhan, she said, spoke to her heart.

From the beginning, disinformation sparked the idea that Asians spread the COVID virus. Such scapegoating continues to fuel ugly incidents in the United States. Compestine said her friends took to demonstrations, Instagram and YouTube to fight back against the demonization of the Asian American Pacific Islander community. She found her own way, by writing a book that aims to humanize the Chinese people.

Throughout, food is an integral element of “Morning Sun.” Compestine projects unbridled enthusiasm for Wuhan’s cuisine. “It’s the best in all of China,” she proclaimed, adding that she’s particularly homesick for its morning markets full of fresh fish and produce.

Indeed, food is never far from her mind, perhaps because, as a child, she was always hungry. Meat and sugar were rationed and sometimes unavailable. Her grandmother taught her how to cook, she said, in an apartment hallway shared by five families. They had no kitchen, no oven, Compestine recalled, “but sharing food is how we show our friendship and love.”

Sharing food is what Mei does too, and that’s what Compestine hopes American children can learn from the character’s example.

“I want them to know how wonderful the people in Wuhan are and how delicious the food is,” she said. “Most importantly, I want them to know that young people can make a difference. This darkest time can bring out the best in people.”

Morning Sun in Wuhan

By Ying Chang Compestine

(Clarion; 208 pages; $16.99; ages 8-12)

Hicklebee’s presents Ying Chang Compestine: 3:30 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 10. Free. 1378 Lincoln Ave., San Jose. www.hicklebees.com

Book Passage presents Ying Chang Compestine: Noon Sunday, Nov. 13. Free. 51 Tamal Vista Blvd., Corte Madera. www.bookpassage.com

I'm so thrilled to share that Morning Sun in Wuhan was featured on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle Datebook!

I hope you will enjoy reading the article!

_____________________________________________

Bay Area chef/author Compestine turns COVID fears into lesson about compassion

Susan Faust November 8, 2022

Updated: November 9, 2022, 6:01 pm

Wuhan is not just the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s what East Bay author Ying Chang Compestine wants to show in “Morning Sun in Wuhan,” a multifaceted novel set at the start of the outbreak in early 2020 that reads like a love letter to her beloved but beleaguered birthplace.

The story centers on 13-year-old Mei as she copes with grief, plus COVID-induced fears and isolation. Her mother recently died of an accident, and her father has 24/7 duties as a respiratory doctor at Yangtze Hospital. With the deepening crisis, Mei is left on her own to play a computer cooking game and prepare food, at first, mostly for herself.

Thus, slipped into Mei’s gripping, day-by-day, monthlong account are passages of WeChat conversations and 10 easy-to-make recipes. (I tried out the lettuce cups, kung pao beef and hot dry noodles. Delicious!) Not surprisingly, Mei loves to cook — after all, Compestine is a TV chef, food consultant and cookbook author.

A child of the Cultural Revolution, Compestine emerged from its brutality and deprivation to joyously celebrate Chinese culture and cuisine in her 17 books for children, all published in the U.S. (Three more out this fall.) “Morning Sun in Wuhan” is no exception. But intertwined are other goals: to encourage girl power, counter racism, honor selflessness and extol community spirit.

Nearly three years ago, Compestine was set for a trip to Wuhan when her best friend in China called about a new virus. “Don’t worry, it’s not transmitted human to human,” Compestine recalled her friend telling her. Then Compestine remembered her mother’s advice: “Always listen to what is not being said. … You grow up in the Cultural Revolution … you have to survive.”

That’s when Compestine canceled her trip. Two weeks later, a quarantine locked down the city.

The situation was dire — a mysterious illness, overrun hospitals, not enough medical equipment or protective gear, no known treatment, food shortages, bodies piling up. Compestine found herself going crazy with worry for her family and friends. Far from the chaos, she said she cooked constantly and stayed up late to keep an eye on the stream of coronavirus updates.

“I watched all the news. It was just getting darker and darker, and I was just devastated,” she told The Chronicle during a recent video call from her home in Lafayette.

Desperate to know what was happening, Compestine relied on information from Chinese American friends, phone calls to her brother in Wuhan, TV news reports and blogs, some quickly blocked by the sensitive Chinese government. One day, still during the height of the pandemic, Compestine read about a group of young volunteers cooking for frontline workers.

“That’s when I saw that I have to write about this,” she said. “You know, this is goodness in the darkest time. I spent a lot of nights thinking about what I would do. … I probably would find a way to help too.”

And that is just what Mei does in the book. She distributes groceries in her apartment compound and enlists other children to work in an emergency kitchen to feed the hungry. Her story emphasizes how the people of Wuhan came together to share and survive.

Video clips of actual events in Wuhan are the basis for harrowing scenes in the book, Compestine said, such as a hospital nurse besieged by patients and the frantic girl chasing after an ambulance carrying away her dead mother. “It’s like a hell, like the end of the world,” the author said of seeing those scenes. “It just made my heart break.”

Photos from the time provided more on-the-ground detail. For example, Compestine could see how, without approved protective equipment, people had to improvise, turning plastic water jugs into helmets, and bras and grapefruit peels into masks.

After her acclaimed first novel, 2007’s “Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party,” Compestine had no intention of writing another middle-grade novel. That fictionalized memoir about growing up during the Cultural Revolution dredged up deep pain from her past. Her parents, both doctors, were denounced as enemies of the state. She was ostracized at school and lonely. But, the COVID crisis in Wuhan, she said, spoke to her heart.

From the beginning, disinformation sparked the idea that Asians spread the COVID virus. Such scapegoating continues to fuel ugly incidents in the United States. Compestine said her friends took to demonstrations, Instagram and YouTube to fight back against the demonization of the Asian American Pacific Islander community. She found her own way, by writing a book that aims to humanize the Chinese people.

Throughout, food is an integral element of “Morning Sun.” Compestine projects unbridled enthusiasm for Wuhan’s cuisine. “It’s the best in all of China,” she proclaimed, adding that she’s particularly homesick for its morning markets full of fresh fish and produce.

Indeed, food is never far from her mind, perhaps because, as a child, she was always hungry. Meat and sugar were rationed and sometimes unavailable. Her grandmother taught her how to cook, she said, in an apartment hallway shared by five families. They had no kitchen, no oven, Compestine recalled, “but sharing food is how we show our friendship and love.”

Sharing food is what Mei does too, and that’s what Compestine hopes American children can learn from the character’s example.

“I want them to know how wonderful the people in Wuhan are and how delicious the food is,” she said. “Most importantly, I want them to know that young people can make a difference. This darkest time can bring out the best in people.”

Morning Sun in Wuhan

By Ying Chang Compestine

(Clarion; 208 pages; $16.99; ages 8-12)

Hicklebee’s presents Ying Chang Compestine: 3:30 p.m. Thursday, Nov. 10. Free. 1378 Lincoln Ave., San Jose. www.hicklebees.com

Book Passage presents Ying Chang Compestine: Noon Sunday, Nov. 13. Free. 51 Tamal Vista Blvd., Corte Madera. www.bookpassage.com

Published on November 17, 2022 13:54

•

Tags:

article, articles, books, diversity, middlegrade, news, newspapers, sfgate

October 26, 2022

SWEEPSTAKE CLOSED. Thanks to all who entered!

SWEEPSTAKE ALERT!

SWEEPSTAKE ALERT!13 days left before my novel, MORNING SUN IN WUHAN, comes out! To celebrate, I’ve partnered with Zwilling USA for a sweepstake!

The grand prize is a signed finished copy of MORNING SUN + Zwilling’s dragon carbon-steel wok with lid, which you can use to cook all the delicious recipes featured in the novel. Two runner-ups will receive signed copies of MORNING SUN IN WUHAN.

NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. ENTER HERE!

Published on October 26, 2022 12:56

September 29, 2022

A Letter to the Readers

Morning Sun in Wuhan

Dear Reader,

In the winter of 1987, I left my hometown of Wuhan, China, to study in the U.S. Even today, I still dream at night about playing in the hospital compound where my parents worked as doctors, shopping in the vegetable markets with my grandma, and taking long bus rides across the Yangtze river bridge to visit my friends.

At the beginning of 2020, I had my bags packed for a lecturing tour in Southeast Asia. My last stop would have been Wuhan. For months, my girlfriends and I chatted excitedly over WeChat, planning the fun activities we would do once I got there: an evening boat ride down the Yangtze river; dressing in traditional clothes and getting professional photos taken in a studio; singing Karaoke at a friend’s new apartment; visiting the famous Hubu Alley and sampling all the local delicacies. Most importantly, I wanted to visit my childhood home in the hospital compound one last time before it was demolished to make room for a skyscraper.

Then one late night in early January, I received a surprise call.

“Ying, you are welcome to stay at our home, but I can’t accompany you anywhere,” said my friend, whose husband held a high position in the government. She continued with an unusually high, chipper voice. “There is an unknown virus spreading around Wuhan, but it’s not transmitted between humans.”

I detected fear and caution in her words. Growing up during the cultural revolution, I became accustomed to people speaking in code. My mother used to tell me to pay attention to what was not being said. The next day, I canceled my flights. Two weeks later, Wuhan was placed under quarantine.

In the following months, I spent every waking hour watching the news, checking Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, talking to family and friends in Wuhan, and following every development of the situation there. My heart ached every time I saw a photo or video of patients crowding hospitals, medical workers collapsing in exhaustion, and people being blockaded in their homes.

I retreated to the one thing that always brought me comfort: cooking. I cooked the Wuhanese dishes my grandma taught me and shared them with my Chinese friends. We exchanged whatever information we had from China and reminisced about our happy times with family and friends back home.

As the situation worsened, I couldn’t help but wonder how my father, a dutiful doctor, would have responded and how my younger self would have reacted. When I read about a young woman leading a volunteer group, cooking for frontline medical workers, it was like seeing a ray of sunlight through the dark clouds. The idea of preparing food for others resonates with me personally and culturally, as, in Chinese culture, food has always played an important role in binding communities together. I began following a blog written by one of the young volunteers. When I learned one of my friend's nieces was volunteering in the group, I interviewed her over WeChat.

The image of Mei formed in my mind. Her voice emerged naturally, as I, too, know what it felt like to act brave as a young girl, even when I was scared. I decided to write a book about the bravery and selflessness of these young people.

Although the pandemic has touched everyone in the world, few know what life was like in the epicenter at the start, and perhaps even fewer know the rich culture of Wuhan and its resilient people.

At its heart, Morning Sun In Wuhan is not merely a book about the pandemic but a tale about kindness, love, and community. It’s a love letter to my birth city and a reminder that one person’s actions have the power to make a difference, that the darkest times can bring out the best in people, and that young people can make an impact in the world.

I hope you will enjoy the book!

Best,

Ying

Dear Reader,

In the winter of 1987, I left my hometown of Wuhan, China, to study in the U.S. Even today, I still dream at night about playing in the hospital compound where my parents worked as doctors, shopping in the vegetable markets with my grandma, and taking long bus rides across the Yangtze river bridge to visit my friends.

At the beginning of 2020, I had my bags packed for a lecturing tour in Southeast Asia. My last stop would have been Wuhan. For months, my girlfriends and I chatted excitedly over WeChat, planning the fun activities we would do once I got there: an evening boat ride down the Yangtze river; dressing in traditional clothes and getting professional photos taken in a studio; singing Karaoke at a friend’s new apartment; visiting the famous Hubu Alley and sampling all the local delicacies. Most importantly, I wanted to visit my childhood home in the hospital compound one last time before it was demolished to make room for a skyscraper.

Then one late night in early January, I received a surprise call.

“Ying, you are welcome to stay at our home, but I can’t accompany you anywhere,” said my friend, whose husband held a high position in the government. She continued with an unusually high, chipper voice. “There is an unknown virus spreading around Wuhan, but it’s not transmitted between humans.”

I detected fear and caution in her words. Growing up during the cultural revolution, I became accustomed to people speaking in code. My mother used to tell me to pay attention to what was not being said. The next day, I canceled my flights. Two weeks later, Wuhan was placed under quarantine.

In the following months, I spent every waking hour watching the news, checking Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, talking to family and friends in Wuhan, and following every development of the situation there. My heart ached every time I saw a photo or video of patients crowding hospitals, medical workers collapsing in exhaustion, and people being blockaded in their homes.

I retreated to the one thing that always brought me comfort: cooking. I cooked the Wuhanese dishes my grandma taught me and shared them with my Chinese friends. We exchanged whatever information we had from China and reminisced about our happy times with family and friends back home.

As the situation worsened, I couldn’t help but wonder how my father, a dutiful doctor, would have responded and how my younger self would have reacted. When I read about a young woman leading a volunteer group, cooking for frontline medical workers, it was like seeing a ray of sunlight through the dark clouds. The idea of preparing food for others resonates with me personally and culturally, as, in Chinese culture, food has always played an important role in binding communities together. I began following a blog written by one of the young volunteers. When I learned one of my friend's nieces was volunteering in the group, I interviewed her over WeChat.

The image of Mei formed in my mind. Her voice emerged naturally, as I, too, know what it felt like to act brave as a young girl, even when I was scared. I decided to write a book about the bravery and selflessness of these young people.

Although the pandemic has touched everyone in the world, few know what life was like in the epicenter at the start, and perhaps even fewer know the rich culture of Wuhan and its resilient people.

At its heart, Morning Sun In Wuhan is not merely a book about the pandemic but a tale about kindness, love, and community. It’s a love letter to my birth city and a reminder that one person’s actions have the power to make a difference, that the darkest times can bring out the best in people, and that young people can make an impact in the world.

I hope you will enjoy the book!

Best,

Ying

Published on September 29, 2022 10:38

January 7, 2018

My New Baby "The Chinese Emperor’s New Clothes" is Born!

How often are we willing to peel back the happy façade we present on social media to share our struggles and failures? As a writer, life is not always full of flowers, starred reviews, and multiple awards. It consists of countless lonely hours of writing, rejection, self-doubt, and revision.

With the recent birth of my baby, my new book: The Chinese Emperor’s New Clothes, let me give you a full disclosure: I worked on Emperor for 13 years. It was rejected by 20 editors! Each time I sent my baby out, I was full of hope. When he came back, rejected, I would spend days doubting my abilities as a writer. But like a loving, infinitely persistent mother, I kept on. I re-structured the story every way I could think of. I wrote variations from the point of view of every major character in the book. I spent days working on one sentence and hours finding the perfect word. I was determined to improve my inadequate baby because he represented part of me - my bitter-sweet childhood growing up during the Chinese Culture Revolution.

When one of the best editors in the country (and the world) finally bought my baby, he paired me with the world-renowned, bestselling illustrator David Roberts, who beautified my baby beyond my dreams. I hope you will meet my adorable baby soon!

To find out more about the book, you can go to Abrams Books.

With the recent birth of my baby, my new book: The Chinese Emperor’s New Clothes, let me give you a full disclosure: I worked on Emperor for 13 years. It was rejected by 20 editors! Each time I sent my baby out, I was full of hope. When he came back, rejected, I would spend days doubting my abilities as a writer. But like a loving, infinitely persistent mother, I kept on. I re-structured the story every way I could think of. I wrote variations from the point of view of every major character in the book. I spent days working on one sentence and hours finding the perfect word. I was determined to improve my inadequate baby because he represented part of me - my bitter-sweet childhood growing up during the Chinese Culture Revolution.

When one of the best editors in the country (and the world) finally bought my baby, he paired me with the world-renowned, bestselling illustrator David Roberts, who beautified my baby beyond my dreams. I hope you will meet my adorable baby soon!

To find out more about the book, you can go to Abrams Books.

Published on January 07, 2018 22:04

•

Tags:

childrens-illustrated