Simone Zelitch's Blog

June 5, 2024

Towards a Judaism without Gender?

What follows was just published in the online Reconstructionist journal Evolve and develops some ideas I first discussed in an earlier blog post about Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of time.

A few weeks ago, I gave a devar Torah at my Reconstructionist minyan, Dorshei Derekh, on what one website called the grossest parshah in the Torah: Tazria. It follows a previous parshah about unclean animals and creeping, crawling things that are temei’im — in other words, defiled. In Parshat Tazria, we move on to our own unclean bodies, and most of the parsha concentrates on leperosy– its symptoms and related prohibitions. This was Dorshei Derekh’s monthly Anti-Oppression Devar Torah, and with this in mind, I focused on the concept of “defilement” and its larger, social and political implications.

Parshat Tazria begins with proscriptions around childbirth:

When a woman at childbirth bears a male, she shall be unclean at the same time of her menstrual infirmity. On the eighth day, the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised. She shall remain in a state of blood purification for thirty-three days; she shall not touchany consecrated thing, nor enter the sanctuary until her period of purification is completed. If she bears a female, she shall be unclean two weeks as during her menstruation, and she shall remain in a state of blood purification for sixty-six days

Leviticus 12:2 (as translated in The Jewish Study Bible [boldface and italics mine]).

Of course, the first 21st-century question is this: Why twice the length of time for a girl? Given the context of the book of Leviticus, perhaps this is self-evident. Girls, after all, are doomed to a regular cycle of defilement and purification: tum’ah [Impurity] and taharah [Purity]. Rules around menstruation are coming up soon, in Chapter 15.

Then there’s the next set of verses: Once the required time is over, the woman must take a lamb and turtle-dove to the priest for a burnt offering and sin-offering before she can enter a state of taharah/purification.

Why a sin-offering? You give birth. What is the sin? In this case, the rabbis did discuss this point in detail. It’s all about the blood.

Or rather: the discharge. That was the word rabbis used regularly — a certain kind of blood that comes from a certain kind of place — not the veins of the body, not the urinary tract. It comes from the uterus. The Mishnah Niddah even includes an elaborate system of discharges and degrees of impurity with colors ranging from red to green to black that is far more clinical than the parshah’s passage about leprosy.

Interestingly, there is a male equivalent to the “impure” fluid women expel during menstruation and childbirth. It’s semen — more to the point, spilled seed. When a man expels seed, he can’t read Torah alone or otherwise engage in study or prayer-life until he is ritually cleansed of this “emission.” There’s even a name for a man who spills his seed: ba’al keri, which means, literally, someone who has endured a mishap or accident.

So why are these emissions and discharges impure? Here is some speculation. Perhaps it’s because they’re accidental. They are beyond our control. Along the same lines, the blood and tissue expelled during childbirth is beyond our control, and of course, there’s nothing deliberate about menstruation. It happens. In this sense, women, too, are ba’alot keri — ladies of the mishap.

Here’s another question: What about genitalia that expel these accidents? When we’re born, they are born with us. From that initial accident come accidents that follow. Women don’t spill seed, and men don’t menstruate. Are those penises and uteruses that we have when we are born also something that we don’t control — in fact — keri: accidental?

I came of age in the late 1970s, during a surge of radical feminism. We were all about our bodies, which were, of course, ourselves, our breasts, the hair under our arms and on our legs, and especially, the interior and exterior life of our uteruses and vaginas: how they make us feel, their changing cycles and what they expel. Menstruation was a superpower. PBS broadcast a play by Wendy Wasserstein called “Uncommon Women and Others,” and one of its characters announced: “I just tasted my own menstrual blood!” I never did, but I got the point.

Along those same lines, Jewish radical feminists re-framed the role of women in the do-it-yourself ethos of that era. Here, I don’t mean women taking on the traditionally male-exclusive roles of laying tefillin or reading from the Torah, but rather women grabbing the specificity of our Jewish women’s bodies with both hands: deep wells, holy vaginas, sacred wombs, Miriam the Prophetess shaking her tambourine and dancing through the open, throbbing slit of the parted waters (yes, I mean it!), new rituals that turn curses into blessings, Red Tents, a mikvah redefined as Women’s Space. In fact, we declared that tum’ah is the same as taharah. Our bodies and secretions are not accidents. We deliberately claimed them.

Yet what does it mean when we say that the body we’re born with to be “ourselves”? If we think about it (and I think we’ve all begun to think about it), why should the sex assigned at birth define us? Certainly, why should that body define Jewish practice? Returning to the first few verses of Parshat Tazria, if the sexual assignment of a boy or girl at birth is accidental, why should it shape everything that follows? Why is it cause for pride and celebration? Such celebration sees that body as a kind of “essence” of self-hood that is magical because it is inescapable. Essentialism is a word with troubling connotations: exclusive, chauvinistic, Romantic “blood and soil” ideology. It’s seductive, and it’s a trap.

What if Parshat Tazria did not begin with the birth of a girl or a boy? Suppose those categories were missing. What would determine the length of time that the woman remains impure?

Who was the first person I met who rejected gender labels? Around 10 years ago, my nibling — a cool word for my sister’s non-binary kid — took on the name Ze, and the pronoun They. More recently, my friend D began to identify as non-binary and altered their name.

It took a while for me to get my mind around all this. I would forget to use the right pronoun. I urged these people to be patient with me. Sometimes, they were. Yet the more I thought about it, the more that non-binary gender identity felt like a step forward. Why not let go of the rules? Refuse to let gender be a power? Make it a plaything! Frankly, when I put on a dress, lipstick and high heels, I’m playing a role that isn’t who I am. I might as well be in drag. I call myself a cis-woman — in other words, I feel at home in the sex and gender I was assigned at birth — but what does that even mean? Why not reject those categories altogether? As time goes on, more and more I think of non-binary people as emissaries from the future.

In my little tour of the marvelous website Sefaria, I found that rabbinic commentaries have plenty to say about non-binary Jews, though the word is never used. The 12th-century Mishneh Torah of Maimonides contains lengthy instructions for women who give birth to a child of indeterminate sex, and contradictory readings that call for androgynes to fulfill the commandments of both men and women. It declares that they cannot marry or bear witness. Then, there’s another category, a tumtum, whose external sex organs aren’t clearly developed.

Yet those commentaries also have space for affirmation. Midrash states that the first human God created was both male and female (as in “male and female, [God] created them”). Of course, in readings from this century, we find inclusive prayers, and a thorough reconsideration of laws of family purity that keep LBGTQAI+ people in mind. I am sure that people in my minyan write such liturgy. A few years ago, a trans Jew, Brin Saloman, released an open-source siddur that was expanded from an earlier version created by the Nonbinary Hebrew Project that includes a prayer for transitioning from one gender to another.

So, I’ve been thinking a lot about gender lately. Apparently, I’m not alone. In her book Gender Trouble, the philosopher Judith Butler argued that the conventions of male and female identity are constructs. Most recently, her new book Who’s Afraid of Gender acknowledges that many people are afraid to talk about this stuff, or simply can’t do so in a rational, honest way.

In that spirit, here’s a related question: What about people who transition from female to male, or male to female? A year or two ago, my non-binary friend D transitioned. She had said she’d come to hear my devar Torah that day, and frankly, I was both disappointed and relieved that she couldn’t be there because I was nervous about asking her these questions: If we decide that gender is a construct, that gender is a set of rules that are meant for bending, then what does it mean to “transition”? Why take on a new gender and stay there? As I say this, I fear being called a TERF — in other words, a trans-exclusionary radical feminist. I also want space to raise these questions, and that space is hard to find.

The morning that I gave my devar Torah, I asked the minyan: How many women here wear tallit? I didn’t even have to ask: almost all of us did, myself included. I knew a lot of the women there lay tefillin. How many men in the room recited the traditionally female blessing over the Shabbat candles? Quite a few present raised their hands. Then: How would a woman’s mikvah respond if a trans woman appeared? Would she be asked if she menstruates? These rituals are powerful, and yes, they are tied to the cycle of women’s bodies. Should they be?

Then, as is the custom in our minyan, I posed a question for discussion. I struggled with the wording: What would a Judaism with meaningful rituals, but without gender look like?

Dorshei Derekh Minyan is packed with rabbis, some of whom were editors or authors of the Reconstructionist prayerbook Kol Haneshamah, and unsurprisingly, the discussion that followed was extensive and often erudite: gender-free translations of the Torah; experiences with Jewish mysticism and the female manifestations of God; the man and woman present in each person; and so on. Yet none of this got to the heart of what I’d hoped we’d discuss, and after a while, I realized that I’d asked the wrong question.

What I really wanted answered was this: Can ritual be powerful if it’s not tied to our bodies — male or female? Judaism, as I understand it, is rooted in the Earth, and in our flesh and blood: harvest, rain, cycles of birth, fertility and death. Therefore, Judaism is embedded in those mishaps, things we cannot control — the rhythms of the natural world. Consider the word “trans” and its connection to “transcendence.” Is “transcendence” a Jewish concept? I’m not a rabbi, yet rising above the body and crossing over physical reality is difficult to reconcile with my own conception of Jewish life. “Transcendence” implies a kind of arrogance, rising “above” the physical, correcting accidents, draining swamps to make the desert bloom. The last phrase was chosen deliberately. Zionism, too, is a kind of “transcendence” — rising above what European Jews became and transforming ourselves into something new. What, exactly, do you rise above when you cross over?

As I searched for photographs to add to this blog post, I came across one of Abby Stein, a descendent of the founder of the Hassidic movement Baal Shem Tov. Abby studied at an ultra-orthdox yeshiva, and left the movement in 2011 when she transitioned from male to female. According to one interview in CNN, after the birth of a son, she felt as though her gender was “punching me in the face.”

At this point, I step back again and ask: Who the hell am I? I’m not my friend D, who feels at home in her life now, maybe for the first time. I have other friends who have transitioned across gender-lines from one pronoun to the other, for whom gender is not a plaything but serious business. I can’t share their “lived experience.” The phrase “lived experience” is often used to describe the stories of people under threat, the source of life choices that can’t fit into so-called “reasonable” categories. As someone who has not faced what these friends have faced, perhaps the most ethical response to my questions about gender and transcendence is probably to postpone this interrogation for a while, and begin, instead, by asking them to tell their stories.

Who’s afraid of gender? To be honest, maybe I am, and I must have the courage and openheartedness not to interrogate trans-people about gender categories but to ask them about their own lives and their own transitions. As for my earlier question about Jewish rituals, a new generation of Jews is already shaping prayers and spiritual practices that come out of lives I have not lived and choices that are their own. At Dorshei Derekh, I ended my devar with a Blessing for the Community from the Inclusive Siddur Project. I reproduce it below:

May our Authority in Heaven be your help

at every time and moment.

And let us respond: Amen!

May the One Who blessed our patriarchs Avraham, Yitzḥaq and Ya’aqov;

and our matriarchs Sarah, Rivqah, Raḥeil, Lei’ah, Bilhah and Zilpah

bless all this Holy congregation

together with all Holy congregations,

them and all that is theirs,

and those who bring together houses of assembly for prayer

and those who bring together minyans

for those who cannot leave their homes

and those who come into their midst to pray

and those who provide candles for lighting

and drink for qidush and havdalah

and food for guests and justice for the meek

and all who occupy themselves with the need of the community faithfully.

May the Holy Blessed One pay their wage

and turn every illness away from them and heal all their bodies

and pardon all their sins and send blessing and success

to all the works of their lives

together with all Yisra’eil, their kin.

And let us respond: Amen.

March 9, 2023

Star of David

Last December, I was at a science fiction convention, hoping to spark interest in the paperback of my alternative history, Judenstaat. I lingered by my copies in the dealer’s room, and got to talking with Laurie Edison, a photographer and jewelry designer. Her stuff was gorgeous and intense, and like its maker, a little witchy. I had a feeling that the earrings and pearl necklace I bought had a story behind them, but part of me didn’t want to know it.

It wasn’t long before I pitched my novel about a Jewish State established in Germany. She, in turn, told me about a personal project. She was making Jewish stars in bronze and sending them to Jews. The deal was this: the Jews would have to wear them.

It was—she said—a way to openly mark yourself as Jewish in a time when attacks on synagogues and other Jewish institutions are on the rise. She didn’t have to explain. Many friends of mine—men and women both– have started wearing yarmulkes in public as a way to defiantly assert Jewish identity. I should also note that I always make a point of letting my Community College students know I’m Jewish a few weeks into the semester.

I thought about Laurie’s offer for a while. Then I said no. Here was my reason at the time: The Jewish Star is at the center of the flag of Israel. Even then, the answer felt dishonest, but it was the best answer I could give.

Last May, I was in Israel and Palestine, doing research for a novel-in-progress. It wasn’t exactly a calm before the current storm. I was in Jerusalem the day of the funeral of the Al Jazeera reporter, Shareen Abu-Aklah, when the Israeli police beat mourners and nearly overturned her casket. That evening, I wandered through the Machane Yehuda market where Israeli flag-draped bars were packed with men singing along to a song about soccer and world harmony. As I traveled to the West Bank city of Nablus, we passed settlement after settlement as Israeli flags fluttered on both sides of the bypass road. I began to be reminded of a long-ago trip through Mississippi where I was so surrounded by Confederate symbols that for the first time in my life, the sight of an American flag brought relief.

There was no equivalent relief that May. The flag of the Palestinian Authority flew in Nablus but it was plastered over with hundreds of martyr posters. From the roof-deck of my hostel, I’d hear gun-shots at night: Israeli soldiers? Palestinians testing weapons? A wedding party? I left with a sense of the banked fury of the young men I met, not least towards the Palestinian Authority. I’m not surprised that the new militia, The Lion’s Den, was founded in Nablus. It was certainly in the process of forming when I was there.

Yet, what I want to write about here is this: when I was in Nablus, a city known for its proud militance and history of resistance, a city almost entirely Muslim and fervently anti-Israel, the most revelatory and intimate moments I had there were when I let Palestinians know I’m a Jew. First there was the architect and community leader, Naseer Arafat, the author of Nablus, City of Civilizations, who’d responded to my email about Nablus by offering to be my guide to the city. I wrote him before I arrived, uncertain how he’d respond. He wrote back: “If I had my worries I would have been clear and straightforward from the beginning”. He never mentioned it again, yet as we sat on a hilltop by the ruins of Sebastia, and he reflected with profound honesty about his life, was it a response to my own honesty? I can’t know.

I told Sara, a marvelous accounting student I’d met on the street, that I was Jewish after she treated me to the best kunafa in the city. I told Mai, the manager of my hostel and a comparative literature student. We discussed Dostoyevsky, a Palestinian novel called Return to Haifa, and the Holocaust. I didn’t tell everyone. The young men who shared their anger at the Palestinian Authority said, “You’re Christian, right?” I think I nodded. I didn’t tell old men I met through Naseer who had taken part in the 1967 Palestinian General Strike. Still, it turned out that just about everyone at the guesthouse knew. They gave me free coffee anyway.

.A deeper question might be this: why did I feel the need to tell these Palestinians that I was Jewish at all? Did I want them to know a Jew who wasn’t holding a rifle? Did I want to somehow complicate their images of Jews? I absolutely didn’t think about it on those terms. Somehow, withholding that part of myself just felt wrong in a way I can’t articulate, and under those charged circumstances where so much felt at risk, letting these open-hearted people know I was a Jew felt like giving them a gift—no strings attached. They didn’t have to change the way they thought about Jews, let alone Israel. Not at all.

I’m not a believer in stable identities or primary identities. We are all at the center of crosscurrents that make the word “identity”, at best, pointless, and at worst, dangerous. Yet, I am a Jew. Again and again, my novels turn back to Israel in ways that feel rooted in my contradictory imagination. When people reveal their own mixed emotions and divided hearts, I want to take the risk and do the same.

After Nablus, I spent a few days in Tel Aviv to decompress. I stayed in a neighborhood not far from the beach, and blessedly free from mass displays of Israeli flags. Yet just before I flew home, I read a report about Jerusalem Day. Ten thousand Israelis streamed through the Old City of Jerusalem, draped in those flags with those blue Stars of David in the middle, shouting “Death to the Arabs” and “May your village burn”, kicking in the grates of the closed shops of the Muslim Quarter, attacking cars and houses, pepper-spraying old women. It was —this is the only word that fits—a pogrom. Outside my Tel Aviv window, someone on a scooter passed by singing cheerfully.

I thought, with tremendous clarity: Israel is not a Jewish State. It uses the symbols of Judaism. The flag is modeled on a tallis—a prayer shawl. Hebrew is a language adapted from our liturgy. A lot of Jews live in Israel. I will never stop feeling drawn to that place. Yet in terms of everything I know and feel about what being Jewish means, Israel has no right to call itself Jewish.

This brings me to the Star of David that Laurie offered. If I believe that Israel has appropriated that symbol, then why shouldn’t a wear it? Why can’t I take ownership of the symbol on my own terms? Well after I met her, I turned this question over and over, and that’s when I realized that I was afraid.

I’m still not sure of the source of this fear. Is it a fear of facing anti-Semitism? Is it more a fear of casual assumptions about what I believe—including about Israel? If I could wear a tee-shirt that reads: “Not a Zionist” along with the Jewish star, would it make a difference? Is it actually a fear of being visibly marked? It isn’t the way that Black people are marked by the color of their skin or people with visible disabilities are marked and judged before they’re known, yet it’s inviting a comparison. In Nazi Germany, I would have been marked with a yellow star. I wouldn’t have a choice. Is wearing the star all the time a weird appropriation of the symbols of the Holocaust?

Here’s the truth: When I tell my students that I’m Jewish, when I told a small number of Palestinians in Nablus that I’m Jewish, it’s a gift I give them in exchange for what I hope to get in return. If I always wear the Star of David, what does it mean? I’m exposing a part of myself—and a deep and complex part—to people who may not deserve it. The symbol is not about asserting pride. In many ways, it’s about asserting vulnerability. Is that who I am? Is that who I aspire to be?

Well, reader, I thought about it. Then, I thought some more. I wrote to Laurie and ordered the star. It came two weeks ago. She’d told me that it wouldn’t look at all like the star in the middle of the Israeli flag, and she was right. It was two smallish, longish, overlapping bronze triangles. My first response was: this looks like something my mother would have worn in the 1970s. Then: it’s kind of beautiful, but will I really wear it? I put it the necklace on, and the hammered halves glowed, falling just below the neckline of my sweater. The star felt startlingly visible. I wore it to school the next day, and felt a hypocritical relief that my college lanyard partially covered it.

I’ve wore that Star of David necklace steadily. None of my colleagues or students have mentioned it. Wearing that necklace doesn’t feel quite right. It casts a spell. My teaching rhythm’s off. I get a little prickly about small grievances. I suspect these tics will pass, but then, I wonder: is the Star of David in the middle of the Israeli flag a little like the Star of David I wear on my sweater? Am I demanding something?

September 1, 2021

Reading Marge Piercy’s “Woman on the Edge of Time” in 2021

A friend of mine recently came out to me as nonbinary, someone I’d known as a gentle, bearded man. The beard is gone, but there doesn’t seem to be any essential difference in demeanor. The friend now wears pastel V-necked T-shirts, gets manicures, and has longer hair, but is otherwise the person I’ve know for years. Maybe a name is now available for an identity that had been there from the start.

You might notice, gentle reader, that I’m avoiding the pronoun “they” as singular. My sister’s kid— I now know the extremely useful term for non-binary niece or nephew, nibbling—has gone by “they” for a while now, but I’d rather use a pronoun that was asserted forty-five years ago: per.

As in: my friend likes to tie per long curls back, and joins per partner for a manicure. Per V-necked T-shirts are brighter than the ones per used to wear.

I’m getting this pronoun—and everything else I’ll write about here—from Marge Piercy’s 1976 novel Woman on the Edge of Time.

I’m getting this pronoun—and everything else I’ll write about here—from Marge Piercy’s 1976 novel Woman on the Edge of Time.

The premise is a very 1976 one. Courageous, depressed and desperate Connie Ramos bashes her niece’s pimp on the head with a bottle, and ends up committed to a mental hospital, where she’s thrown into the violent ward and doped up on Thorazine. She’s also in contact with Luciente, an emissary from 2137 who introduces her to a communitarian society where a revolution has eliminated economic, racial and gender inequalities.

In fact, there is no defined gender in the utopia of Woman on the Edge of Time. Unlike our “they”, the pronoun, “per” carries no particular associations about gender nonconformity. It’s used universally. I should note that because the novel is anchored in Connie’s point of view, she identifies the people she meets as men or women, but as far as the characters themselves are concerned, their penises or vulvas aren’t defining: they’re a source of play and pleasure. There’s plenty of sex in 2137, and no names for distinct sexual orientations. Passions aren’t orientations. Per loves whom per loves.

It take a while for Connie Ramos to get her mind around all this, of course, and as Connie learns, the liberation comes at a price. At one point, Connie is led to a humming, mushroom-shaped chamber that enclooses an aquarium—the “brooder” where embryos grow. It’s a vision similar to Huxley’s Brave New World, but Huxley’s embryos are genetically modified to create a fixed caste system. In this case, the aim is quite the opposite. Luciente’s explanation is worth quoting at length:

at a price. At one point, Connie is led to a humming, mushroom-shaped chamber that enclooses an aquarium—the “brooder” where embryos grow. It’s a vision similar to Huxley’s Brave New World, but Huxley’s embryos are genetically modified to create a fixed caste system. In this case, the aim is quite the opposite. Luciente’s explanation is worth quoting at length:

“It was part of women’s long revolution. When we were breaking all the old hierarchies. Finally there was that one thing we had to give up too, the only power we ever had. In return for no more power for anyone […] Cause as long as we were biologically enchained, we’d never be equal. And males never would be humanized to be loving and tender’”

Once “born”, the children have three co-mothers, a term which, of course, has no connection to bearing children. Connie—and perhaps the reader—recoils in disgust when a man opens his shirt to breast-feed. It’s all so planned, she thinks, so artificial.

The embryo-brooder and male breastfeeding are not the only artificial elements in Piercy’s 2137. Connie is told that Luciente and the others in the village are Wampanoag Indians. They’re light-skinned, dark-skinned, bearded, clearly of African, European, Asian and Mexican descent, but Wampanoag Indian is their “tribe.” All of the villages have tribes: Ashkenazi Jewish, Harlem Black and so on, a way to preserve cultural traditions while “breaking the bond between genes and culture” so there would be “no chance of racism again.” Yes, people are raised in a tribe, but they can also switch tribes (which are also called “flavors”). Black members of Luciente’s tribe could move into the Harlem Black village any time they chose. Presumably so could Rachel Dolezal.

Luciente and the others in the village are Wampanoag Indians. They’re light-skinned, dark-skinned, bearded, clearly of African, European, Asian and Mexican descent, but Wampanoag Indian is their “tribe.” All of the villages have tribes: Ashkenazi Jewish, Harlem Black and so on, a way to preserve cultural traditions while “breaking the bond between genes and culture” so there would be “no chance of racism again.” Yes, people are raised in a tribe, but they can also switch tribes (which are also called “flavors”). Black members of Luciente’s tribe could move into the Harlem Black village any time they chose. Presumably so could Rachel Dolezal.

So how do we read Woman on the Edge of Time in 2021? Is this novel a utopian vision, or a dystopia where language enforces a kind of nonbinary conformity, and racial and ethnic identity is reduced to a cafeteria of “flavors”? It’s also worth noting that history itself is deliberately scrambled: one of the culture’s many holidays celebrates the anniversary of the Seneca Falls conference where Harriet Tubman delivered her famous “Ain’t I a Woman” speech, after which she stormed the Pentagon. In celebration, children smash a paper pentagon, and there’s candy inside. I think I was supposed to be charmed. Instead, frankly, I felt seasick.

Piercy appears to hedge her bets. When we meet a member of the Harlem Black tribe, she is, in fact, Black, and Connie is relieved to meet a fellow Latina whose village on the Texas border At some point, we learn that Cree land remains protected, and presumably, it is a place for actual members of the Cree Nation. In fact, Connie herself expresses many of a reader’s possible misgivings, a useful narrative device. Not everything’s resolved.

You’ll have to read the novel for yourself. It’s still in print. What I write here doesn’t include many other elements o f Woman on the Edge of Time: Connie’s experiences in the mental hospital as the subject of a sinister experiment, her complex, tragic past, the Wizard of Oz parallels between her fellow inmates and characters in the 2137 future, the war between two alternative futures and Connie’s role in that war, and of course, the possibility that everything is a hallucination.

f Woman on the Edge of Time: Connie’s experiences in the mental hospital as the subject of a sinister experiment, her complex, tragic past, the Wizard of Oz parallels between her fellow inmates and characters in the 2137 future, the war between two alternative futures and Connie’s role in that war, and of course, the possibility that everything is a hallucination.

Who reads this novel now? We all should. I have decided that nonbinary people are emissaries from the future. What about other binaries and social constructs? Are they hallucinations too?

July 20, 2021

Excavating James Michener’s The Source

My new novel will take place in 1970, and a central character is a young American Jew, and a member of the Zionist Youth Group Habonim. She’s smart and single-minded, and even if I don’t share her politics, I like her a lot and am curious to find out what will become of her as she heads to Israel for a year of volunteer work on an archaeological dig.

When I begin to research a novel that takes place in the past, I tend to use what I call the sandwich method. I begin generally, write most of a draft, and save specifics for a point when I better know the direction of my story. The key thing early on is this: getting inside my character’s head. What are the rhythm of her thoughts– this theoretical girl of mine? How would she see the world?

Of course, my character would have read The Source.

My parents must have had a copy of that novel, along with Golda Meir’s My Life and Moshe Dayan’s Living with the Bible on their shelf just below their very scary portrait of David Ben Gurion. Indeed, for me, reading The Source in public felt a little embarrassing, like wearing a Young Judea tee shirt that doesn’t fit anymore. I considered carrying it around in a paper bag.

My parents must have had a copy of that novel, along with Golda Meir’s My Life and Moshe Dayan’s Living with the Bible on their shelf just below their very scary portrait of David Ben Gurion. Indeed, for me, reading The Source in public felt a little embarrassing, like wearing a Young Judea tee shirt that doesn’t fit anymore. I considered carrying it around in a paper bag.

Published in 1965, The Source is a door-stop of a novel, designed to take us through the history of the imaginary Tel Makor, an archaeological site in the Galilee.

A Tel is a mound formed by layers of ruined settlements. This one is excavated by an Irish American, and two Israelis (an academic, and a sexy female authority on ceramic shards), with assistance from a friendly Arab with a British accent. With present-day Israel as starting point, the novel travels the fifteen levels of the Tel from the bottom up, reaching back to the Stone Age– each with their piece of what I now know is called “Material Culture“, a primitive scythe, a fertility goddess, a glass vial for perfume, a golden menorah, and so-on– leading to Israel’s ’48 war and a battle to “liberate” Safad.

of what I now know is called “Material Culture“, a primitive scythe, a fertility goddess, a glass vial for perfume, a golden menorah, and so-on– leading to Israel’s ’48 war and a battle to “liberate” Safad.

Well, reader, it was a slog, but I finished it. After 1080 pages of this weirdly compelling information-dump, at some point, I realized that I wasn’t reading Zionist propaganda. I was reading a particular American writer’s perception of the history of a particular few square miles of the Galilee, which (post Jesus) he begins to call The Holy Land.

For me, reading a novel like The Source is an exercise in double-think. through the eyes of my novel’s protagonist, and also as a cultural artifact.

. On those terms, a few things surprised me.

James Michener’s Israel of the early sixties is a placid place. Early on, we see a lovely, white stone house with “graceful Arabic arches” which the archaeologists plan to use as a base. The Arab assistant informs the American that it was probably owned by an Arab olive-grower a few hundred years ago. Of course the olive-grower was more likely expelled or fled in 1948, but tensions arising from that war– both internal and external–play no part in the contemporary Israel of the novel. Instead, we read about conflicts between European Jews and Mizrahi immigrants, tactless kibbutzniks and vulgar Jewish-American capitalists, and perhaps most critically, between religious laws and secular principles which are perhaps most corrosive and complex, which leads me to… When it comes to religion, Jews can’t compromise, and that may not be a good thing. Yes, Jews are central to the novel which is, after all, based on an imaginary archaeological dig in Israel, but historically those Jews are exiled from the city of Makor time

“graceful Arabic arches” which the archaeologists plan to use as a base. The Arab assistant informs the American that it was probably owned by an Arab olive-grower a few hundred years ago. Of course the olive-grower was more likely expelled or fled in 1948, but tensions arising from that war– both internal and external–play no part in the contemporary Israel of the novel. Instead, we read about conflicts between European Jews and Mizrahi immigrants, tactless kibbutzniks and vulgar Jewish-American capitalists, and perhaps most critically, between religious laws and secular principles which are perhaps most corrosive and complex, which leads me to… When it comes to religion, Jews can’t compromise, and that may not be a good thing. Yes, Jews are central to the novel which is, after all, based on an imaginary archaeological dig in Israel, but historically those Jews are exiled from the city of Makor time  after time because those Jews refuse to bend. In fact– dare I say it– throughout the generations, Michener’s Jews are down-right stiff-necked. In some cases– say, during the Spanish Inquisition– those qualities are presented as admirable (and bring them back to The Holy Land). Yet more often, Jews are taken to task for caring more about Law more than Mercy (sound familiar?) It’s an old Christian Anti-Semitic trope. It’s an unresolved conflict in the novel, a paradox, because Jewish law often presented as petty and counterproductive, but as far as Michener is concerned, following law is what makes a Jew a Jew. And here’s the real surprise: Yes, Palestinians were always in Makor– and by extension, Israel. They were just called something else. I’m a

after time because those Jews refuse to bend. In fact– dare I say it– throughout the generations, Michener’s Jews are down-right stiff-necked. In some cases– say, during the Spanish Inquisition– those qualities are presented as admirable (and bring them back to The Holy Land). Yet more often, Jews are taken to task for caring more about Law more than Mercy (sound familiar?) It’s an old Christian Anti-Semitic trope. It’s an unresolved conflict in the novel, a paradox, because Jewish law often presented as petty and counterproductive, but as far as Michener is concerned, following law is what makes a Jew a Jew. And here’s the real surprise: Yes, Palestinians were always in Makor– and by extension, Israel. They were just called something else. I’m a little slow on the uptake, but at some point I realized that the Stone Age bee-keeper named Ur moved through the generations, became a Cannanite, became a Jews, became a Christian and became a Muslim, and that the Ur family outlasted empire after empire, and his right to the land is evident because each Ur from Makor will switch to the winning side to stay there. Jews don’t. I don’t want to give too much away, but you won’t be surprised to learn that as Michener presents the outcome of battle of Safed in 1948, the band of valiant Jewish soldiers discover that every single Arab had fled the city. One Jewish soldier actually goes after them in a stolen jeep, pleading with them to stay. And one Arab does–the descendant of Ur with roots all the way down the fifteen levels of the Tel to the Stone Age Makor cave.

little slow on the uptake, but at some point I realized that the Stone Age bee-keeper named Ur moved through the generations, became a Cannanite, became a Jews, became a Christian and became a Muslim, and that the Ur family outlasted empire after empire, and his right to the land is evident because each Ur from Makor will switch to the winning side to stay there. Jews don’t. I don’t want to give too much away, but you won’t be surprised to learn that as Michener presents the outcome of battle of Safed in 1948, the band of valiant Jewish soldiers discover that every single Arab had fled the city. One Jewish soldier actually goes after them in a stolen jeep, pleading with them to stay. And one Arab does–the descendant of Ur with roots all the way down the fifteen levels of the Tel to the Stone Age Makor cave. So what did I learn from reading The Source? To be fair, I got a good base-line understanding of biblical archaeology which came back in almost cut-and-pasted passages when I went on to read nonfiction on the subject, I also learned far more than I ever cared to learn about how a Christian looks at the Crusades . I came away wondering this: how did Americans think about Israel when The Source was published in 1965?

Prior to the 1967 War, Israel and American had yet to form their current symbiotic relationship. Of course, there was Leon Uris’s Exodus, written in 1958 and of course, its film version from 1960. indeed a work work of Zionist propaganda and a wildly popular one, but that novel doesn’t address what happened once the state was established in 1948. What about Israel in 1950 or 1960? Did Americans look beyond the overheated tangle of Paul Newman and Sal Mineo, and imagine what this state became?

Prior to the 1967 War, Israel and American had yet to form their current symbiotic relationship. Of course, there was Leon Uris’s Exodus, written in 1958 and of course, its film version from 1960. indeed a work work of Zionist propaganda and a wildly popular one, but that novel doesn’t address what happened once the state was established in 1948. What about Israel in 1950 or 1960? Did Americans look beyond the overheated tangle of Paul Newman and Sal Mineo, and imagine what this state became?

Here’s a question: Was The Source actually a response to Exodus? How would Michener feel about the clam: “This land is mine! God gave this land to me.” (Lyrics by Pat Boone!). The excavation of Tel Makor makes it clear that the land doesn’t belong to Jews alone. James Michener was no Zionist. He was a lapsed Quaker, a liberal and a humanist. He liked to dig into history, and like all biblical archaeologists of the period, he imposed stories on his artifacts, what Nadia Abu al-Haj calls “facts on the ground”, However, it was a humanist story. Now, I’m imposing my own story on this artifact too.

So yes, my character would have read The Source. She would have loved the details, been attracted by its humanism, and perhaps would have seen hope in the consistent presence of that Ur family in Tel Makor. She would have wondered– as some other Zionists did– if the Arabs in Israel were Jews who’d forgotten that they were Jews. Yet if she wanted to explain Zionism to a non-Jew, she would have been more likely to suggest that they watch Exodus. Besides, who doesn’t love Paul Newman?

As ever, books lead me to other books, and if I really want to know how Americans saw Israel before and after the 1967 War, I have a lot more reading to do. Chances are, I’ll have to find a used copy of Exodus. Then, I’ll really need that brown paper bag.

I’ll keep you posted.

January 8, 2021

Video Games

A few weeks ago, I was part of a Hanukkah reading at my local bookstore, Big Blue Marble. Or I should say, of course, that I wasn’t at Big Blue Marble, and neither was anybody else. Our host appeared to be at the bookstore, but eventually revealed that she was using a virtual background and was actually in her apartment a few blocks away.

Such is pandemic life, and it came at the end of a semester of online teaching. I’ve been a professor at Community College of Philadelphia for almost half my life. In public, I disparaged the experience of teaching online, but privately admitted its advantages. Here’s a confession: recently, the dynamics of a face to face class had become overwhelming– students texting, cross-talking and challenging me when I tried to get them to focus, basic classroom management that had seemed much easier in the twentieth century. Online, these issues disappeared. In short, I felt more in control than I had in years.

Now, my fall grades would soon be submitted, and here I was in a virtual space with an audience of fifty, as poets and prose-writers read their work in turn. I wouldn’t have to interact with anyone, or even look alert. The writers were mostly women on the far side of middle age, earnest progressive Jews like me. and I let myself drift knowing that at some point, I’d have to un-mute and read a story, but that wouldn’t happen for a while.

Then someone broke in. “Is SEE-mone ZEE-litch here?”

Not a poet. Not a writer of prose. It was a man– a loud one– and I fumbled weirdly for the chat-box as though he had posted rather than shouted my name, but then the screen was taken over and we saw a grainy gyrating torso with the shirt pulled up to the nipples. The man called again– “SEE-mone ZEE-lich”– then something else I couldn’t catch, as the the torso gave way to a black and white video: cheerful marching Nazis and a jaunty song:

“We’re going on a trip to a place called Auschwitz. It’s shower time little Jewstein–”

I think this was the version the Zoom Bomber used.

I think this was the version the Zoom Bomber used.

The song lasted for maybe five seconds, and then, the host regained control of the screen and got rid of him– them– who knows how many. I was still I was still reverberating. That guy– whoever he was– knew my name.

So much for control. The evening went on, and although I read my little Hanukkah fable like a good girl, I couldn’t have felt less present. Instead, I considered: I’d posted about the event on Facebook. Yes, only my Facebook friends can read that page, but the post was forwarded– to whom? I know, I know, Zoom-bombers have targeted Black, LBGTQ and Muslim events ever since there was such a thing as Zoom, but I kept wondering, absurdly and obsessively. Did I know that voice? Did I know that torso? There was something simultaneously alien and intimate about it all, even the mispronunciation of my name.

And then, I thought: What if it were one of my students?

That thought was absurd, but it came quickly, and it stayed. Early in the fall semester, when I’d missed office hours for Yom Kippur, I’d told my students why. A month later, one student wrote an anti-Semitic response to an assignment, and then disappeared from the class. When I’d had prior Zoom conferences with that student, the background had been grainy, so close to what I saw during the Zoom-bombing that I felt I almost recognized the torso, but that was impossible. The whole situation was impossible, and I wallowed in paranoia, feeling defiled, in free-fall, out of control.

When I told friends about what happened, they gave plenty of advice about how to avoid it happening again: build a kind of Zoom fortress with a waiting room, get an assistant to vet all comers, institute mandatory muting and a chat-lock, not to mention disabling the screen-share to avoid offensive You Tube videos. Most people making these suggestions knew that trolls— a great word for folks like the Zoom-bomber– will be trolls. They’ll find a way into the fortress somehow, and storm it in super-hero costumes with their pipe-bombs. The great seduction of these platforms is this: we think that if we master them, learn how to play their games, then we’ll be safe.

I tried to play a different kind of game last summer when I designed my online courses. We use a pl atform called Canvas and all summer, I built structures as complex and well-supported as cathedrals. Assignments, quizzes, discussions, conferences, everything connected, and it was actually fun to poke around, get creative. I even created a friendly, cartoon avatar to attach to my messages and comments. Isn’t she cute?

atform called Canvas and all summer, I built structures as complex and well-supported as cathedrals. Assignments, quizzes, discussions, conferences, everything connected, and it was actually fun to poke around, get creative. I even created a friendly, cartoon avatar to attach to my messages and comments. Isn’t she cute?

Even after the semester started, I’d sometimes spend twelve hours a day in front of my laptop, obsessively correcting any flaws I found. Every time I discovered a new hack and applied it, the course felt more cohesive and successful. The structure– with its weekly Welcome videos, its constant communication, its required conferences– created opportunities for intimacy that I never had in a physical classroom.

Yet even during conferences, I seldom saw my students’ faces. They kept their cameras off, and for countless reasons: poor internet connection, no quiet place to work, and most of all, no way to control their environments. These are students at a community college in a city; they’re caring for children or elderly parents; they work in big-box stores; they take double-shifts at I-Hop when other servers test positive for Covid-19, or they test positive themselves, as three of my students did. Perhaps the greatest epidemic of all was depression and anxiety disorder. I know that several students dropped the course for just that reeason, and those were only the ones who told me so.

I kept thinking: if I create a perfect course, if I work out every last bug in the system, write meaningful assignments, get all the students laptops, connect them with counselors, plead with them to turn in a rough draft, plug every last hole that may sink my class, then they’d be okay. That course is under my control, and at the very least, it can be a space that didn’t disappoint them in a world where trolls roamed freely. I did try, probably too hard, but not everyone could be okay, and my control was an illusion.

Canvas, like Zoom, is what we have now, and we are bombarded with advice on how to make these platforms more rational and secure. They can be mastered, and if you’re like me, you can become obsessed with mastery. You’ll check the settings and re-check them, I wonder now in retrospect if my Canvas course became aspirational, a game that I was playing and trying to win. Are these platforms by their nature alienating to the point where we can lose sight of their purpose? Is alienation, in fact, their purpose? Perhaps. They aren’t intended to replicate their face to face equivalents. They go in a different direction, a direction that may well outlast this pandemic

There is no moral to this story. In a week, I’m back in the online classroom, teaching the same courses, with the same material and the same structure. I’m also participating in another event sponsored by Big Blue Marble with enhanced security. I’ll try not to spend twelve hours in front of my laptop, and I’ll hope this new event isn’t Zoom-bombed. However, what I fear most is that we will grow far too comfortable with these video games, the kind where cathedrals or fortresses are constructed brick by brick, and forget how to live in a messy world full of surprises.

I might find a world without surprises easier, but I will resist it, somehow.

March 19, 2020

Reading The Plague in the Age of Social Distancing

I’ve taught The Plague to my community college students more than once. It’s one of the books that most people figure they’ve outgrown. Set in the mid-1940s, in Oran, a small Algerian city which faces an epidemic of bubonic plague, the novel feels pretty fusty to a contemporary reader. Its first-person plural narration, its exclusively male cast of characters, and perhaps most of all, its patent obliviousness to the Arabs who make up ninety percent of the population of the Algeria, all of these things would make most of us unlikely to pick that book up again.

And yet, during these early days of our own epidemic, I found myself turning back to the Modern Library Edition with the green cover and the block-cuts of the Grim Reaper at the start of each chapter. I’d remembered a few things: the creepy squish of dead rats underfoot, the landlord’s bulging ganglia, the initial denial of the people of Oran who kept on doing business, going to the cinema, and filling cafes like they were on holiday.

That’s where some of us were a few days ago, clicking or scrolling on our phones or laptops, then heading outside to clear our heads. My students mostly work in places like Target and Chipotle, and back then, it might not have occurred to them that their vacation would be permanent. Then, just as was the case in Oran, the order came—in Camus’s case by telegram: “Proclaim a state of plague stop close the town”.

Each character in The Plague responds to this crisis in a way that defines him. A priest sees the plague as God’s punishment; a criminal has never felt more free; journalist scrambles to be reunited with his lover. Centrally, as the official response to the plague collapses, a group of volunteers takes up the work of sanitation. They know that plague is contagious, but these volunteers resist isolation, and fight what Camus calls the “abstraction” of the plague, reminding each other that the epidemic “is the concern of all”.

Obviously, we aren’t forming sanitation squads to fight COVID-19. The best strategy to fight contagion is social distancing. For many people, social distancing is not a cultural shift, not if we just re-frame it as, say, physical distancing. Furthermore (the argument goes), aren’t we lucky to have so many powerful ways to reach out to each other? As I write this, I’m figuring out how to teach my students online, and the frantic Facebook messages among my colleagues list at least ten different platforms for posting lectures, giving quizzes and collecting assignments.

As we adapt to this new normal, it’s worth remembering that social distancing benefits corporations like Amazon, which is now in the process of hiring a hundred thousand new employees. At a point when independent businesses were beginning to assert themselves as places where communities could gather, those gatherings become virtual, mediated by Skype or Zoom or Facetime. Comcast has recently offered free Wi-Fi to students like my own—along with a transition to paid service in several months, a service that students previously accessed though their schools or libraries. It’s not a matter of whether these trends will be permanent. They already are. COVID-19 just creates an opportunity to make them public policy.

Yet COVID-19 is not a hoax created by Amazon; it’s real, as is the need to avoid contaminating ourselves and others. At the same time,what will happen when this crisis ends? In The Plague, when the sanitation squads clear out attics and cellars, and dispose of the dead, they look forward to a goal beyond the passing of the plague. Time had stopped; it must go forward. Lovers part; they must be reunited. Most of all, they long for an end to exile, to face not inward but outward, and become part of the world again, a world shaped by their own courage and solidarity.

The Plague is sometimes considered an allegory for French resistance to the German occupation, a reading that Camus rejected, yet certainly, the dilemmas he sets up have philosophical resonance. In The Plague, official responses are not only inadequate, but worse than useless. No one trusts authorities, and shifting information makes government edicts all the more dubious. As several characters state—in a key phrase—the trouble with official responses is that they “lack imagination”. What they can’t imagine—what no “official” entity can imagine—is a future.

It’s possible to take the epidemic seriously, but challenge the direction of official policy, particularly to curb corporate power as it becomes all the more powerful . We find one valuable model in the work of the Italian group, Power to the People, which has focused their efforts on prisoners, and low-income workers in Amazon warehouses, and created opportunities for mutual aid that are not just reactions to an epidemic, but are part of the group’s larger political vision.

Of course, we should follow regulations to curb the spread of COVID-19, but we also must consider the kind of world we want to occupy while it is with us and when it is gone. Could we question the assumption that online learning is appropriate for elementary school students? Is there a reason why only online retailers can deliver “non-essential” items? Are we assuming that online platforms are like public parks or sidewalks, public spaces maintained for the public good? Is there a way to maintain solidarity that isn’t virtual? I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I fear that if we don’t use our imaginations, we’ll be living in what Camus calls exile, an abstract, eternal present which will long outlast this plague.

We must not only be imaginative, but vigilant. Social distancing is larger than a response to COVID-19. Social distancing came before this epidemic, and it will outlast this epidemic, with all of its cultural and economic implications. After all, as Camus reminds us, plague, never really dies. He writes “[…] that it can lie dormant for years and years in furniture and linen-chests; that it bides its time in bedrooms, cellars, trunks and bookshelves; and that perhaps the day would also come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

December 11, 2019

Waveland

This was just posted in “Snowflakes in a Blizzard”. Many thanks to Darrell Laurant who curates the site– a wonderful place to discover small press books like Waveland!.

THE BOOK: Waveland.

THE BOOK: Waveland.

PUBLISHED IN: 2015

THE AUTHOR: Simone Zelitch

THE EDITOR: Linda Gallant.

THE PUBLISHER: The Head and the Hand.

This is a Philadelphia press established by Nic Esposito. It began with a series of themed almanacs as well as chapbooks which were sold through local vending machines. I knew some people involved with the press and admired their innovative marketing techniques and their role in the Philadelphia literary community. Also, the books they publish are beautiful. That matters.

SUMMARY: In 1964, a thousand white Northern college students went to Mississippi , hoping to call call attention to that state’s brutal suppression of African Americans. They taught in Freedom Schools, and helped register voters for alternative elections in the hope of challenging the legitimacy of the all-white Mississippi delegates at the Democratic Convention. Waveland focuses on one of those Freedom Summer volunteers, Beth Fine, an abrasive outsider who brings…

SUMMARY: In 1964, a thousand white Northern college students went to Mississippi , hoping to call call attention to that state’s brutal suppression of African Americans. They taught in Freedom Schools, and helped register voters for alternative elections in the hope of challenging the legitimacy of the all-white Mississippi delegates at the Democratic Convention. Waveland focuses on one of those Freedom Summer volunteers, Beth Fine, an abrasive outsider who brings…

View original post 1,211 more words

November 16, 2019

Mutual Aid

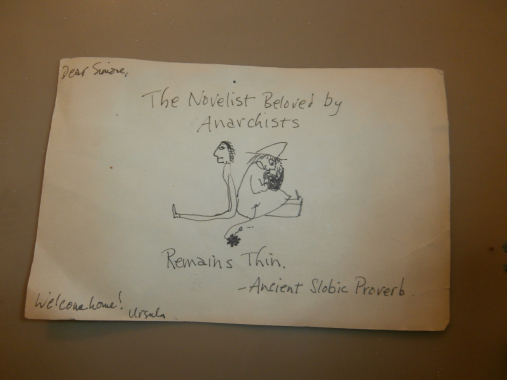

I have no record of my first letter to Ursula K. Le Guin. I’ve kept identical black notebooks since I was fourteen, and I looked at the first ten of them and couldn’t find a record of what motivated me to write. The letter must have gone to Avon, her publisher at the time. What I do know is the date of her reply: On Febrary 19th, 1980, when I was seventeen. I wrote in all caps: “I GOT AN ANSWER FROM URSULA LE GUIN”.

And this wasn’t just a note. It had a typed envelope and the letter inside was typed on stationary with Le Guin in curly typeface. She thanked me for what I said about the production of The Lathe of Heaven. Then, I must have asked her about the anarchism in The Dispossessed because she went on “The major source for ODO’s [caps all hers] is probably Kropotkin.” Then, after a few lines about Emma Goldman (“she was such a sweetie”) Le Guin ended, “I fully agree with you that you are going to be a writer. I don’t know why. I just believe you when you say it.”

Of course, I sent her a terrible short story, and she sent back her response, a typed single-spaced savage page. Now, thirty-eight years later, I think: What established writer does this sort of thing? I actually suspect that Ursula did this sort of thing, and all the time. I have no real evidence, and a hasty Google search for stories like my own only led nowhere. Of course, we all know that a generation of writers—particularly women—are in her debt. Of course, we can turn to the back of books—particularly books published by independent presses—and see her testimonials. Yet why do I assume that some of those women had been corresponding with her for a decade or more before that publication? When she died, were there dozens of women pulling out their forty-yea- old letters or postcards? Did they save them in a box like I did?

In my case, after that early exchange, with the exception of a letter which generated a weird little postcard based on who-knows-what with a drawing of “smiling running shoes” I swore I wouldn’t write to Ursula Le Guin until I had something to say. Ten years later, my novel about a failed medieval fourteenth- century peasant revolt was published by Black Heron Press. , Le Guin did like the book, and the testimonial she wrote on the back didn’t save The Confession of Jack Straw from obscurity, but it probably was the reason why the book ended up on the shelf of Wooden Shoe, an anarchist bookstore. I told her so, and she sent a postcard: “The Novelist Beloved by Anarchists Remains Thin – Ancient Slobic Proverb”.

Somehow, when we met in person our relationship felt more abstract. The first time was soon after my marriage, in 2002. We met outside of Powell’s, and then the two of us head to her place. She was even shorter than I thought she’d be, brisk, almost businesslike, though by all measures, glad to see me. As we entered her house, she told me that she and Charles had just finished reading War and Peace out loud to each other; when I arrived, he was hiding somewhere. Our conversation was collegial enough, but I do remember her saying something about the importance of women writers having mentors, which made me feel a little too much like a project.

The second time I saw Ursula was in 2014 at the conference of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs in Seattle. By then, she was an established literary lioness, known for her of thunderous roaring, particularly against corporations like Amazon. Her emails from the carefully anonymous address were lots of fun. “I hope we can met LIVE! IN PERSON! at AWP.” And finally, as we arranged to meet her in hotel room, “If you need to be in touch with me after Thursday of next week—try my hotel room. Email no good. Zog not travel with computer. Zog very primitive. 4:30 at Zog’s hotel room.”

She said she’d lost her copy of Jack Straw, and I brought a new one plus the two other books I’d published, half a bottle of wine, and a small bouquet of tulips, and there she was, compact as ever, now a little hunch-backed, with her characteristic cap of straight, white hair. She put the flowers in water and offered me some bourbon from a flask which, of course, she took, and we talked about publishing. She was a happy, witty talker. She said, “You’re a mid-list author” and I wanted to say, “No, actually. I’m not on a list at all,” but it did give us a way to talk about the world of publishing, about marketing and boycotting Amazon of course, and how she resigned from the Author’s Guild over their compromise with Google. Then, slowly, the room began to fill with other white-haired Oregonian women, all clearly over eighty; one of them was Ursula’s webmaster. They passed around that flask; one of them took a glass out of the bathroom and took off its little paper cap to pour. I began to feel as though I shouldn’t overstay my welcome.

After that point, Ursula and I corresponded only by email, and not very often: When David Hartwell at the the big science fiction press, Tor, bought my novel Judenstaat (she warned me that some other women he’d published had found their books buried), when Hartwell demanded a blurb from her (She’ll get to it and see if a blurb “rises up”; it didn’t), when Hartwell died suddenly leaving my novel orphaned (He was a star, and I’d be treated well; unfortunately, I wasn’t). Somehow, the medium of email didn’t suit either of us. I missed the squibby pictures on her postcards. I also wondered if somehow my publication at a press like Tor made me less interesting. I did write to congratulate her on her inclusion in the Library of America series, and particularly her selection of her wonderful and mostly-forgotten Orsinian pieces in the first volume. I didn’t get an answer.

I’m fifty-seven now, older than Le Guin had been when she first got my first letter. My response to her death was pretty straightforward: I’m grateful that she was honored in her own time-time, that she got to write what she wanted to write, and that her work and opinions continue to matter. She also died before her husband Charles, something that I suspect she would have wanted; you can feel the strength of that relationship in every book she’s written.

And maybe I understand why Le Guin might have answered all those letters from strangers. She wasn’t being altruistic. An anarchist in the Ododian mold doesn’t believe in altruism. Rather, she believed in solidarity in a broad sense, between writers and readers against the forces of markets that tell us what we have to write and algorithms that tell us what we want to read. As Kropotkin writes, “the great principle of Mutual Aid which grants the best chances of survival to those who best support each other in the struggle for life. “

April 28, 2019

My Loud Voice and How I Got It

I haven’t written any blog posts for a while, and miss the opportunity to share my thoughts with folks, somewhere, somehow. Recently, I took part in a panel at the Association of Writers and Writing Programs called “Jewish Women Confront Identity“. It was a really interesting experience, and I am grateful to Irina Reyn who probably suggested my name.

As we sat at the front of a room full of (almost entirely) Jewish women, my fellow panelists referred to a “culture of silence”. For many reasons, my take on female Jewish identity was rather different, as described below.

When I was asked to join you on this panel, I thought a lot about the title. I have a lot to say about Jewish Identity in my work, present in almost all my books, one way or another. How I approach it as a Jewish woman is more subtle, probably more fraught.

Many of you probably know the marvelous Grace Paley story from 1959: “The Loudest Voice“, the one where everyone says to the little girl Shirley, “Be quiet” and—now I’m quoting—“In that place, the whole street groans: Be quiet! but steals from the happy chorus of my inside self not a tittle or a jot!”

You may remember what happens next. Shirley Abramowitz is told to go to the alien territory of a 6th grade classroom where Mr. Hilton—what a goyish name!—finally says, “’My! My! Shirley Abramowitz! They told me you had a particularly loud clear voice, and read with lots of expression. Could that be true?’ ‘Oh yes,’ I whispered. ‘In that case, don’t be silly; I might well be your teacher some day. Speak up, speak up.’ ‘Yes!’ I shouted. ‘More like it,’he said. ‘Now, Shirley, can you put a ribbon in your hair, or a bobby pin? It’s too messy.’ ‘Yes!’ I bawled.”

Jewish identity, for me, has nothing to do with silence. That’s true for the women in my work, and it’s also true for myself. During panels like this one, I don’t need a mic. I sing shamelessly in public. Back home, I teach at a community college and have a classroom full of traumatized students who would benefit from three-minute mindfulness exercises before each class, but so help me, I can’t imagine standing there for three minutes while we all breathe.

So…I’m a loud-mouthed Jew, and frankly need to interrogate the pride I feel about it.

Here’s some context: I went to a progressive Jewish day-school in the ‘70s. A placelike that’s almost impossible to imagine now. We were taught prayer and Torah by hippies in fringed vests who encouraged us to read and pray in subversive ways. Those were the days of the Havurah movement, the First Jewish Catalogue, and do-it-yourself Judaism. We made comic books or Super-8 movies about Jacob and Esau. We considered King David a dubious character. When we came to the story of a rebellion against Moses and Aaron in the wilderness, when rebels declared that everyone was holy, my response was Right On!

The hippie rabbis at my school were men. There was no mention—not at that time and place—of foremothers. And when I first began to write novels, they were about rebellious and subversive men: medieval peasants, de-frocked priests, upstart Hebrews in the wilderness. Did I even think of myself as a girl back then? Not really. Like many people on the Autism spectrum, I didn’t think of myself as having a body, at all. My brain might as well have been inside a brown paper bag that the world would shake once in a while.

Yet my brain was a Jewish one, at least as I define it. I do define it, quite explicitly in my most recent novel which actually is called Judenstaat, where a character sets forth Judaism’s three attributes: We don’t bow down, we cross borders, and we remember. The first attribute, not bowing down. was hammered into me long ago when I heard the Hanukah story of Hannah and her seven sons, as each, in turn, refused to prove obedience to a pagan king, and and each, in turn, was slaughtered. Right on.

Bowing down to authority just wasn’t something that Jews did as far as I was concerned. And growing up where I did and when I did, I made much of the role of Jews in organized labor, in movements against racism, in resistance to authority in every form. I was a pretty arrogant kid.

Of course, we know better. Jews bow down all the time for all kinds of complicated reasons, and in all kinds of depressing ways. The more I wrote and researched, and also the more I considered both political and personal histories, the less judgemental I became. What is the cost of survival? Who do we become? My work grew far more complex as I considered these questions in the context of political and personal history, and I became less interested in bowing down, far more interested in border-crossing and memory.

Increasingly, the central characters in my books are women—alienated, cranky and tender-hearted, broken and defiant. Some of them are also pretty loud. I wondered—in the case of my novel Louisa about a Holocaust survivor—what it’s like if your past follows you across a border? I wondered—in the case of my novel Waveland about a white and Jewish Freedom Summer volunteer in Mississippi—what it takes to realize that good intentions aren’t enough. Finally, and increasingly, I am obsessed with what we remember, and how we remember it, and that, inevitably led me to consider how Jews think about Israel and Palestine, and what we leave out of our stories.

Those are my Jewish heroines these days, and I’ve been told they’re hard to love. They dig up dirt about a past that should stay buried, they don’t respect personal boundaries, and frankly, most of the time, they’re a pain in the ass. They call people out on their hypocrisy, and sometimes they’re pretty tactless about it.

Yes, that’s the phrase: Jewish women call people out. We’re shrill. We’re pushy. We cross borders- or push boundaries– in ways that make people around us feel embarrassed. Yes, these are stereotypes, and I know plenty of Jewish women who have worked hard to use their inside voices. Should we? I don’t know.

I have a friend who is even more tactless than I am. And yes, she’s Jewish (though it doesn’t matter much to her). She may read this, or some of you may read this and send her the link. If so, she’s bound to post about it on Facebook. Her volume isn’t loud in the literal sense, but she’s militant and relentless. Many people have told her that her relentlessness is counterproductive. I have told her that her relentlessness is counterproductive. She doesn’t care. She thinks she’s right. She mostly is right. Sometimes she convinces other people. Sometimes, other people convince her to modify her position, and she changes her mind. One thing we can’t do is convince her to shut up.

Here is an unexpected and instructive consequence: My friend doesn’t hold grudges, maybe because every last thought leaps right out of her. I don’t think she holds anything back at all. She’s left with space to understand and to forgive.

Some of you in the room probably remember how Grace Paley’s story “The Loudest Voice” ends. Shirley Abramowitz is the star of her school’s Christmas pageant. Some of the Jewish grown-ups around her are appalled, some see it as assimilation. Shirley’s father has a different perspective. “Does it hurt Shirley to speak up? It does not. So maybe some day, she won’t have to live between the kitchen and the shop. She’s not a fool.”

Neither are we, I hope. If we’re loud, I hope we’re smart enough to see beyond our ideological and interpersonal shtetls. The world is wide.

I’ll end with Shirley Abramowitz, and her last thoughts after the Christmas Pageant (where, by the way, she played Jesus). “I was happy. I fell asleep at once. I had prayed for everybody; my talking family, cousins far away, passerby, and all the lonesome Christians. I expected to be heard. My voice was certainly the loudest.”

December 9, 2017

What If There Had Been No Balfour Declaration?

We’re living in an alternative-history moment. Given the current political climate, it’s no coincidence that most of us are in full flight from the present. Instead, we look over our shoulders, and endlessly revise the past.

Now, after President Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, here’s one more revision: What if there had been no Balfour Declaration?

[image error]Balfour addressed his declaration to Edmond de Rothschild whose name often appears in anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

November marked the centennial of that 1917 document, which begins: “His Majesty’s Government views with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object.”

The Balfour Declaration was hardly altruistic. As England, France and Italy prepared to divide a defeated Ottoman empire, England wanted access to the Suez canal, a link to their colony in Egypt, and although one could argue that the endorsement grew out of respect for the Zionist project, it also was based on a familiar anti-Semitic trope: Jews have money, influence and power, and it makes good sense to get them on your side.

Far more could be written about division in the world Jewish community about a homeland in the territory of Palestine, or indeed division among Zionists themselves. Indeed, far more could be written about the many promises made to many of the people in the region who hardly expected their homelands to be divided like a Christmas pudding. These subjects have been discussed so thoroughly that it’s hard to get through the dense competing ideologies, and find a clear pattern of legitimate facts.

What haunts me instead is this: Jews, Muslims and Christians lived in Jerusalem, Jaffa and Hebron for generations before those cities were part of a country with fixed borders; rather, those cities and the surrounding countryside were under the jurisdiction of the Ottoman Empire, with a government so inefficient that it might as well have not been there at all. What was life like for Jews in the area that Balfour referred to as Palestine?

This is one of the questions addressed in Menachem Klein’s 2014 book, Lives in Common, which focuses on Arabs and Jews in those three cities before the British Mandate, and

[image error]Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem towards in the last years of the Ottoman Empire

goes on to explore how relationships were transformed by emerging national identities in the years that followed. The early chapters of the book describe a time when Arab and Jew weren’t separate, contradictory categories; in fact, there were Arab Jews, indigenous and integrated into their communities, without distinct national aspirations.

Klein gives us tantalizing portraits of Jewish musicians playing at Muslim weddings, of Jewishan and Muslim families mingling in common courtyards, of bathhouses that date from the Mamluk period used by Jewish women as mikvahs, of the 451 Arabic words that found their way into Yiddish, of cafes in cosmopolitan Jaffa where Arabic mixed with Ladino, and men would gather to play dominoes, talk politics, and read the local newspaper, Falastin.

Of course, these “lives in common” are complicated by real prejudices that pre-date the Balfour Declaration. Under the Ottomans, Jews were second-class citizens, and Muslim and Christian Arabs made clear distinctions between “local” (Arab or Sephardic) Jews and “Muscovites” who were considered invaders, Ashkenazic Jews under the protection of European embassies, whether they were strictly religious and dependent on charity, or secular Zionists farming on property they bought from absentee landlords in Damascus.

[image error]Jewish and Palestinian activists in contemporary Hebron

Yet it’s worth considering: if Britain hadn’t supported Jewish nationalism, would Arab nationalism have turned in the direction of antisemitism? What if the territory we call Israel or Palestine was part of an Arab country with borders that may not in any way resemble the borders we see on maps today? Would Zionists continue farming and reviving the Hebrew language there? If Ottoman restrictions remained, would those Zionists unite with Sephardim, Ashkenazim and Arab Jews to demand full citizenship in this imaginary country?

Of course, this speculation may, in the end, be just as likely or unlikely as the vision asserted in the Balfour Declaration, particularly when we read beyond the initial phrase and find that the document endorses its homeland for the Jews with caveats: “[…] it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine…”

[image error]Hungary’s “Force and Determination Party” uses symbols that evoke the fascist “Arrow Cross”

It is possible for any “national home” to meet the Balfour Declaration’s standards? Israel can’t now, and year by year, that goal feels more remote. Yet Israel is not alone. In 2017, we struggle with the consequences of national homes. The collapse of the Soviet Union, much like the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, left a map to be re-drawn. In this case, the new borders are defined and defended in ways that reflect ferocious ethnic and religious prejudices that we haven’t seen for generations.

So what about Jerusalem, with its gold stone, cramped alleys, angry fanatics, and bedazzled tourists? That city is, of course, a magnet and an incubator for these prejudices. It’s tempting to wish Jerusalem was blasted into orbit as a satellite, a kind of golden moon, an aspiration.

We can wish the same of nations, that identity, language and culture could develop without armies and borders. Some influential Zionists like Martin Buber and Ahad Ha’am explored this possibility. We can’t revise history, but we can revisit missed opportunities and see if they lead us away from the dead end we’ve clearly reached today

As Zionism’s founding spirit, Theodor Herzl, once wrote, “If you will it, it is no dream