Alex Woolf's Blog

March 10, 2015

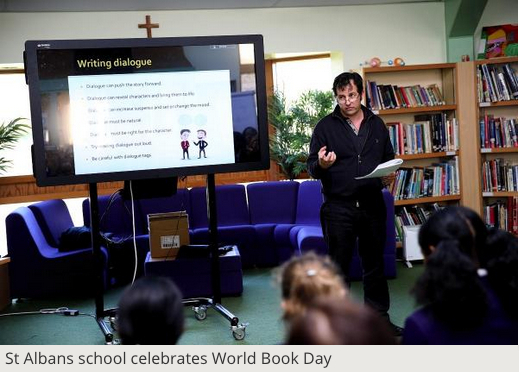

My World Book Week

For a children’s author, World Book Day and the week it falls in is always a very busy time, with schools clamouring for visits. My schedule this year ran like this:

Thursday 26 February: Featherstone Primary School, Southall

Friday 27 February: Townsend School, St Albans

Monday 2 March: Carshalton Boys Sports College, Carshalton

Tuesday 3 March: Immanuel College, Bushey

Wednesday 4 March: writing day: took a forced break from school visits to write a chapter of the Fiction Express book I’m currently working on.

Thursday 5 March (WBD): The Manor Academy, Mansfield Woodhouse

Friday 6 March: Lea Valley School, Enfield

Giving a talk about creative writing at Townsend School

It was an exhausting time for an author who, for much of the year, rarely travels further than the kitchen to make himself a fresh cup of coffee. I was sometimes a little overwhelmed by the noise and the bustle of large, busy schools and my hat goes off to teachers who must face this every day. And yet I found it incredibly fulfilling and beneficial. The students listened attentively during my talks, and they worked diligently during my workshops (well, most of the time!).

Speaking at Carshalton Boys Sports College

I learned as much from the students as I hope they did from me. I learned a little about how kids communicate, what they think about, what books they like to read, and what kinds of things fire their imaginations. Most of all, I was reminded that ‘kids’ is not a category, no matter how much publishers and authors like to think it is, and the phrase ‘Kids are really into this at the moment’ is actually as meaningless as if you replaced the word ‘Kids’ with ‘Adults’. Sure, they’re subject to the usual fads and fashions, just as adults are, and there will always be popular authors and books and genres. But that sort of thing is less obvious when one travels from school to school and you hear such different opinions on what they enjoy reading.

Signing a book at Immanuel College

Their responses to a visiting author are equally unpredictable. I was cheered and mobbed for autographs in one school, and listened to in polite silence at another. In yet another, a reading I did was greeted by spontaneous applause. If there is a generalisation you can make, it’s that kids tend to be honest in their reactions, they don’t suffer fools, and they will always, always ask how much you earn.

Giving a workshop at Carshalton Boys Sports College.

Townsend School, St Albans

September 30, 2014

Dread Eagle print competition

One lucky reader can win this fabulous A3 print of a French airship featured in my book Iron Sky: Dread Eagle. For your chance to win, just answer this question:

Who did Napoleon call “the most powerful and most constant of my enemies”?

Wellington

Churchill

Britain

Time

To enter, click here, and insert your name, email address and answer in the boxes provided.

Good luck!

September 26, 2014

Dread Eagle has launched!

Yesterday, IRON SKY: DREAD EAGLE, the steampunk adventure I’ve been working on for the past two years was published. Already it seems to be getting lots of interest.

Lovereading4kids calls it “Adventurous steampunk at its very best”

Readitdaddy writes: “Alex Woolf sets out his bookworld with rich texture and tapestry, immersing the reader in a parallel universe that is as intoxicating as the choking coal-fumes issuing from every page.”

Here are a few more comments:

“an exciting, action packed novel” Jake Fletcher, age 13

“I found it hard to put the book down” Amelie Chatham, age 11

“I would rate this book five out of five stars” Eloise Mae Clarkson, age 12

In this interview with The Reading Zone, I talk about my inspiration for the book.

There’s also a competition with The School Run to win copies.

Stay tuned for more updates…

July 28, 2014

FEAR: Of the Dark

I’m delighted to have had a story selected for the latest anthology from Siren’s Call, which published this month. My story’s called The House on the Peninsula.

WARNING: For adults only.

What makes your skin tingle? What makes you look over your shoulder sure that something is lurking there? What ratchets your tension level up so high that nothing matters more than what comes next on the page?

The answers to those questions are the ones we sought when we put together this collection of nine stories. Inside these pages you’ll find fear that engages, fear that provokes, fear that drives you to the brink of… Well, everyone has a different precipice when it comes to fear, but the stories selected for FEAR: Of the Dark certainly held our attention.

If you truly enjoy a well written story that engages the senses and prompts anxiety and paranoia, FEAR: Of the Dark may be the perfect collection of short stories for you. And in case you were wondering, it is waiting for you, out there – somewhere; you just don’t know it yet.

Contributing Authors:

Rose Blackthorn, Juan J. Gutiérrez, Jovan Jones, Lars Kramhøft, Lisamarie Lamb, Jon Olson, Zachary O’Shea, Jon Steinhagen, and Alex Woolf

Available for Purchase at:

Amazon:

US | UK | Canada | Australia | Germany | France | Spain | Italy | Japan | Mexico | Brazil | India

May 19, 2014

The Writing Process Blog Tour

Anita Loughrey has kindly asked me to join The Writing Process Blog Tour. The idea is that I say something about my writing process, post it on my blog, and then pass the torch onto three more writers to do the same. And it’ll go on like that until every writer in the world has written about their writing process, and then it’ll stop. I think that’s the idea anyway. You can read Anita’s fascinating and funny contribution to the blog tour at http://amloughrey.blogspot.co.uk/2014...

Anita Loughrey has kindly asked me to join The Writing Process Blog Tour. The idea is that I say something about my writing process, post it on my blog, and then pass the torch onto three more writers to do the same. And it’ll go on like that until every writer in the world has written about their writing process, and then it’ll stop. I think that’s the idea anyway. You can read Anita’s fascinating and funny contribution to the blog tour at http://amloughrey.blogspot.co.uk/2014...

So, here we go with mine…

What am I currently working on?

I’m currently very busy on several projects. On the fiction side, I’m writing the final volume in a series of six stories set in ancient Rome about a young gladiator. I’m also writing a scary short story about a cryptid, provisionally entitled The Big Grey Man, which I’m hoping to get published in an e-zine that’s published my stories before. When I’m not writing either of those, I’m working on any one of about three non-fiction projects. They include a series aimed at young people about what it’s like to grow up in various countries. Photographers based in those countries take photographs of a young person during the course of their day – having breakfast with their family, going to school, doing chores, having fun – and I must write the words for it. That’s not all I’m working on right now, but this could get quite long if I listed everything, so I think I’ll stop there!

How does my work differ from others of its genre?

I write books in lots of genres, so this is a difficult question to answer. But whether we’re talking science fiction, horror, historical, steampunk or time travel, I always try to write the books in my own style and not imitate anyone else in that genre. Although I write books mainly for young people, I try never to talk down to my readers. In fact, I think of them as equals and partners in the journey we set out on together. And that means no compromises. Whatever it is I’m attempting to say, I’ll work and work at it until I find the best way of saying it, using exactly the right language, and not oversimplifying for the sake of it. If that sounds like I write horribly complex stories with loads of long words, then I’ve given completely the wrong impression! I hope my books are clear and fun to read, but I do like to spend an awfully long time honing each sentence until it sounds exactly right. I’m a writing geek in that way – obsessed with words and how they sound. I’ve even been known to read dialogue passages aloud while working in my study, which can come as quite a shock to any members of my family who happen to be passing.

Why do I write what I do?

Most of my writing is commissioned, so I’m writing to a brief. When given free rein to write what I like, I tend towards subjects like the supernatural, the fantastical and the weird. I’m not sure why that should be. It may be because I grew up in a fairly dull suburb of London and my imagination rebelled against my surroundings. Also, I hated school, and perhaps the stories I made up were a way of escaping from that particular reality. It’s something that’s continued into adulthood. Even though I lead quite an interesting and contented life these days, I still feel this overpowering need, every so often, to escape into the other world of my imagination. Writing allows me to do this.

How does my writing process work?

I sit down at my keyboard and start typing…

Sometimes I wish it was that simple. The writing process varies depending on what I’m working on. If I’m writing a scary story, like the one I’m working on at the moment about the Big Grey Man, my starting point is always: what do I find scary? I’m not easily scared by fiction (though I am by real life – a scuttling beetle or a sharp word from my wife can bring me out in a cold sweat!), so there’s a fair chance that if I’m scared by an idea, others will find it scary too. Writing scary fiction is hard, though, because you don’t have the advantage of a creepy soundtrack or clever camera angles and lighting, as horror film directors do. What you can do is to create a journey into terror. The reader has to be a willing partner on this journey, but if they’re ready to partake, a good writer can lead them by a sequence of steps towards a climax that is just as scary as anything in the cinema. First I need to create a real-seeming character that the reader might conceivably care about. Then I introduce something slightly odd into the plot. This might be something as simple as a job offer or a tattooed stranger or a recurring dream. If I do my job right, the slightly odd can quickly become unnerving, the unnerving can become alarming, and the alarming can become, by the end of the story, downright terrifying. It seems quite simple when written down like that, but it is actually very difficult to do well. You have to use things like ‘atmosphere’ and ‘suggestion’ and ‘pacing’, which I won’t write about here because they deserve whole blogs to themselves.

With the gladiator books, I knew I had to work out a plot that contained certain features. Each book had to include a couple of fight scenes. Then there had to be some sort of progress towards solving the central mystery of the series. I had to find important roles for each of the central characters and give them their own story arcs. All this took a lot of planning and flow charts and coffee and late night scribbling of ideas that were usually indecipherable the next morning. And that was before I’d written even a word of the story. The writing of the story is actually fairly straightforward compared to the chaos of plotting. I work from a detailed synopsis, which I frequently alter as the story progresses. The one factor that can sabotage the writing process at this stage, even if you have the most perfectly engineered plot, is a rebellious character. Characters quite often like to do their own thing, and the writer has to be like a wise parent, making constant judgements on whether to let his progeny enjoy themselves, or ruthlessly whip them into line if he thinks they’ve gone too far. In the penultimate gladiator book, one of the main characters falls in love. That wasn’t in the synopsis – it just happened quite accidentally in the writing process. I then had to decide what to do about it. What were the consequences of this sudden drastic change in the plot? More coffee, more flowcharts. In the end, I let nature take its course, but then sneakily manipulated things so that the lovers were parted at the end of the book. Perhaps they’ll meet again in the final volume. I’ll just have to see how things go…

I was told to pass the baton on to three writers, but I could only find two (either because every other writer in the world has already been tagged for this tour, or because I left it too late to find someone). However, I could not wish to pass on the torch (baton, whatever) to two finer writers, both of them stablemates of mine at the interactive publisher, Fiction Express for Schools. I admire their work tremendously. You can read their blogs about their writing process on Monday 26th May.

Stewart Ross

Prize-winning author Stewart Ross was inspired to write by his great-grandfather, a vast Scotsman with a spreading beard who wrote an extraordinary novel (Mildred Murdoch) and masses of rather bad dum-de-dum poetry. After teaching all over the world, Stewart became a full-time author in 1989. He has written numerous books, fiction and non-fiction (a term he hates) for both children and adults. Much of his recent work has been historical fiction, a genre he much enjoys, especially when the past stretches into the future as in his recent YA success The Soterion Mission. (Sequel, Revenge of the Zeds, out in September.) He also writes plays, lyrics and other bits and pieces, and teaches writing in England and France. Stewart lives near Canterbury with his wife, four occasional children and Chess the ageing sheepdog. Each morning he commutes ten metres to work in a large hut in the garden.

In all literary matters Stewart is represented by James Wills of Watson, Little Ltd – jw@watsonlittle.com

Sharon Gosling

Sharon Gosling always wanted to be a writer. She started as an entertainment journalist, writing about television series such as Stargate and Battlestar Galactica. Her first novel was published under a pen name in 2010.Sharon and her husband live in a very small cottage in a very remote village in the north of England, surrounded by sheep-dotted fells. The village has its own vampire, although Sharon hasn’t met it yet. The cat might have, but he seems to have been sworn to secrecy and won’t say a thing.

Sharon Gosling always wanted to be a writer. She started as an entertainment journalist, writing about television series such as Stargate and Battlestar Galactica. Her first novel was published under a pen name in 2010.Sharon and her husband live in a very small cottage in a very remote village in the north of England, surrounded by sheep-dotted fells. The village has its own vampire, although Sharon hasn’t met it yet. The cat might have, but he seems to have been sworn to secrecy and won’t say a thing.

September 12, 2013

Soul Shadows giveaway!

I’m pleased to announce that the publishers Curious Fox are giving away one copy of Soul Shadows to three readers. To enter, click here and fill out the Rafflecopter form.

July 5, 2013

The Boy Who Lost His Tuesday

‘Waldo Stubbs, I want to talk to you.’

Waldo looked up from the workbench in the corner of the Physics Lab. He was surprised to see Reg Fathom, the most popular boy in the school, lurking in the doorway. What on earth did Reg want with him? He was amazed he even knew his name.

Waldo was a short, bespectacled boy of sixteen. Large of nose and squinty of eye, he had yet to grow into the looks that would one day make him his fortune. He had joined Cherry Tree Secondary School four weeks earlier, at the start of the autumn term, and had, so far, made virtually no impression on anyone – or so he had believed.

Reg Fathom swaggered over to where Waldo was seated. Reg was tall and thickset with jet black curly hair and a pair of blue eyes that could melt even the toughest teacher’s heart. He picked up the object the smaller boy had been working on. It looked like a fat, high-tech pen, with sliding buttons and lights on its sides.

‘Please be careful with that,’ pleaded Waldo. ‘It’s full of delicate circuitry.’

‘What on earth is it?’ Reg fiddled with the buttons, making the lights flash angrily.

‘It’s nothing at the moment. I’m hoping it’ll be something one day.’ Waldo reached for the object, but Reg swiftly transplanted it to his other hand. Waldo sighed. He didn’t share his fellow students’ admiration of Reg Fathom. ‘So,’ he asked through tightened lips, ‘what did you want to talk to me about?’

Reg’s handsome face fell into a frown. ‘Oh yes,’ he said, rubbing the cleft in his manly chin with the end of Waldo’s gadget. ‘You’re good at finding things aren’t you?’

‘Not particularly,’ replied Waldo, wondering what Reg might be getting at. Good at losing things – maybe. Good at inventing things – he liked to think so. But finding things? Not to his knowledge.

‘You remember last week when you found Chad Wilkins’ tennis racket in the library. And then the week before that you spotted Evie Nickelbite’s bracelet on the netball court.’

Waldo remembered both occasions. ‘Pure luck,’ he told Reg truthfully. ‘In fact I wasn’t even looking for them at the time, just stumbled on them.’

‘Exactly!’ said Reg. He tapped the tube-shaped object on the workbench for emphasis, to Waldo’s quiet alarm. ‘You weren’t even looking for them. Which proves my point. Imagine how successful you’d be if you actually wanted to find something.’

‘That doesn’t really follow,’ said Waldo.

‘Of course it follows,’ asserted Reg with the self-confidence of a boy who had been praised and flattered almost constantly since nappyhood. ‘And now,’ he added, ‘I want you to find something for me.’ He gave Waldo both barrels of his famously blue eyes.

‘What have you lost?’

Reg twitched his lips. Was there a flicker of nervousness, embarrassment even, on his face? ‘My Tuesday,’ he muttered.

‘And Tuesday would be whom? Your aunt? Girlfriend? Pet cat?’

‘No, I mean the day of the week. You know, the one between Monday and Wednesday. I’ve lost it.’

Waldo took off his round-framed glasses and rubbed them on his sweater, something he often did when nervous or embarrassed. He never dreamed he would feel sorry for Reg Fathom, captain of the school football team, winner of countless drama prizes, fancied by at least three-quarters of the female population of Cherry Tree. Yet the boy had clearly gone nuts – 24-hour-care, straitjacket and padded-cell kind of nuts.

‘How can you lose a day?’ he asked gently, still rubbing his glasses.

‘I’ve asked myself the same question many times,’ said Reg, who was managing to talk pretty normally for a mad person. ‘My Mondays happen as you’d expect them to. So do my Wednesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays. But for some reason, my Tuesdays just … don’t. They fail to turn up. I go to bed on Monday evening and wake up on Wednesday – I’ve no idea why.’

Waldo didn’t trust himself to say anything so he remained mute.

‘I wouldn’t mind so much,’ continued Reg, almost to himself, ‘as Tuesday’s not such a big day in the scheme of things. I’m not missing footie or English, and there’s not much decent telly on that night. It’s more that I’m starting to think I might be getting short-changed – you know, on life. I mean everyone else gets the full complement of seven days, so why shouldn’t I? When you add it up that’s 60-odd days a year that I don’t get to experience.

’52,’ said Waldo. ‘To be precise.’

’That’s right,’ said Reg. ’52 days. Gone. Just like that.’ He clicked his fingers. ‘I’m 16 now. If I live till 86, I’ll lose about … 20 years’

‘Actually about 10 years,’ said Waldo.

‘Whatever,’ grumbled Reg, who clearly wasn’t used to being corrected. ’The point I’m making is that one missing day might not seem such a big deal, but when you add it all up it’s a complete disaster!’

‘When did this start happening?’ asked Waldo.

‘About a month ago.’

‘So you’ve lost four Tuesdays already.’ Waldo thought for a minute. Reg didn’t seem mad, but then mad people often don’t. The horrid thought then struck him that perhaps this was a wind-up. Reg’s mates were probably just outside, in the corridor, sniggering into their hands. But something about the look on the boy’s face – a mix of seriousness and embarrassment – persuaded Waldo that this was no joke, at least not to Reg. ‘Why aren’t you telling all this to a teacher, or your parents?’ Waldo asked. ‘I mean it’s pretty serious.’

Reg absently rolled Waldo’s widget on the workbench surface, making the other boy almost squeak with fear at the damage he might be doing to it. ‘I thought about that,’ said Reg, ‘but I was worried they might all think I’m nuts. I have a certain … image, you see, which I need to preserve. They think of me as, well, a bit special. And someone special like me needs to be rock solid in the head department – which I am of course. But if I told them what I’m telling you, they might start to have their doubts. I can tell you, of course. You don’t move in the circles I move in. In fact you barely register on the radar at Cherry Tree, which makes you pretty ideal for my purposes.’

‘I see,’ said Waldo glumly.

Reg was right, of course, about the circles and the radar thing, but that didn’t make hearing it any nicer. Waldo had always been something of a loner and an oddball. Academically he was a long way ahead of his peers. He sensed their discomfort in his presence. He felt awkward about displaying his knowledge, so tended to downplay it, or simply remain quiet in class. He often felt like someone from the developed world sent among a lost Rainforest tribe and forced to adapt to their ways. His knowledge was useless to him. What he needed was a completely different set of survival skills that he simply didn’t have. Miss Spivey, the head of Science, had thoughtfully offered Waldo the use of the Old Physics Lab for him to pursue his projects. The lab had recently been rendered obsolete, thanks to the completion of the school’s shiny new Science Block, and until the school authorities found it a new purpose, it would be Waldo’s domain. It quickly became a haven for him – the equivalent of the shed in the back garden of his house. When he wasn’t obliged to attend class, he could almost always be found here.

Waldo didn’t know how one would go about finding a Tuesday. He was also unsure about what his options were in this situation. He sensed there was a system of unspoken rules among the Cherry Tree Rainforest Tribe, but he didn’t understand them. When a popular boy such as Reg approached a ‘nobody’ like Waldo for a favour, was there an element of choice in the matter, or did the nobody just have to do it? Waldo had no idea.

‘Um,’ he said, thinking how best to phrase the question. ‘Well,’ he added. ‘As it happens, I…’ Reg looked at him, brow handsomely furrowed. ‘I’m very sorry about your missing day, Reg, really I am. But, you see, I’m a bit busy at the moment with –’

‘With this?’ asked Reg brightly, waving Waldo’s gizmo in the air.

‘Er, yes. Among other –’

‘Not a problem,’ smiled Reg. ‘I’ve thought about that.’ He slipped the device into his inside jacket pocket. ‘I’ll hold onto this for now. That should remove any distractions and give you more time to focus on my little problem. Does that sound okay?’

Waldo was confused. Reg was acting as though he was doing him a favour, but hadn’t he just confiscated Waldo’s invention?

‘I’d rather you didn’t hold onto it,’ he said carefully. ‘Can you give it back, please?’

‘Oh, don’t worry,’ chuckled Reg. ‘I’ll look after it. And I promise you’ll have it back in one piece as soon as I get my Tuesday back.’

Waldo didn’t like that reference to ‘in one piece’ at all. Reg was smiling affably, but his words seemed full of menace. Waldo felt utterly out of his depth.

‘One other thing,’ said Reg. ‘I’d be grateful if you could conduct your investigations discreetly. I don’t want any of my friends or family to find out about what you’re doing. I’ll obviously be as careful as I can with your pen thing, but you never know. Accidents can happen. You know what I’m saying?’

Waldo inwardly seethed, frustrated at Reg’s effortless hold over him and at his own pathetic impotence. What use were ten thousand hours of study if they didn’t equip him to deal with arrogant bullies like Reg Fathom? Reg’s dull yet streetsmart brain had quickly worked out that the ‘pen thing’ was of value to Waldo. He was right to assume that Waldo had a special affection for the object. It was, admittedly, an invention still looking for a function: inspired in conception, brilliant in design, yet – so far – useless in application. He was sure it did have a purpose – it would be beyond tragic if it was destroyed before he discovered what that purpose was. He simply had to get it back. He swallowed and tried to keep the shaking out of his voice. ‘Okay. I’ll see what I can do.’

‘Good man!’ grinned Reg. ‘I knew you were someone I could trust. Now I don’t know about you but I’ve got a class to get to.’

Since starting at Cherry Tree, Waldo had made virtually no impression on anyone – virtually, but not quite entirely. Rose Duvalle was the exception. It was very hard to explain the friendship between Waldo and Rose – if indeed it could be called a friendship. Waldo’s feelings towards her wavered between bemused tolerance, irritation and mild fear. As for Rose, he often wondered why she persisted with him, for he seemed to cause her nothing but disappointment. He hadn’t courted the friendship with her – he wouldn’t have had the skills to do so even if he’d wanted to. Rose hadn’t really courted him either – they’d just ended up sitting next to each other in class and she’d taken offence at something he’d said. She came up to him afterwards to demand an explanation or an apology, and things had sort of gone on from there.

He caught up with her in the canteen at lunchtime. He was late, as usual, and when he arrived at their customary table with his tray, she was already halfway through her main course. Rose was wearing the look that had become so familiar to him: accusing eyes, flushed cheeks, small mouth in a pout. ‘Do you think it’s pleasant eating alone?’ she said.

‘I’m sorry,’ mumbled Waldo.

‘Perhaps you should try inventing something useful in that lab of yours – like an alarm clock!’

Waldo decided to change the subject. As he tucked into his sausages and mash, he told Rose about his encounter with Reg Fathom. He observed with amusement her desperate attempts not to appear impressed. She glanced around the room, sipped her water, fiddled with her food, but her eyes could not conceal her fascination. ‘He says he’s lost his Tuesday? Well! He’s quite clearly insane, poor boy.’

‘Yes, he may well be, but if I’m going to get my invention back, I’ve got to try and find it for him.’

‘Oh, what a pickle you’re in,’ she laughed scornfully. ‘I bet you now wish you’d never found Chad Wilkins’ tennis racquet and Evie Nickelbite’s bracelet.’

‘You could say that,’ said Waldo sadly. ‘And even if I did find those things on purpose, which I didn’t, a day is hardly like a bracelet or a tennis racquet. I’m not exactly going to stumble on it on the netball court or in the library, am I?’

Rose gasped in mock amazement. ‘A day is not like a bracelet or a tennis racquet! A quite brilliant observation, my dear sir, if I may say so!’

It had taken Waldo a while to get used to Rose’s sarcasm – a form of humour that had been virtually unknown to him before he arrived at Cherry Tree. But by now, he was learning to ignore it. ‘The problem, surely, must lie in Reg’s head,’ he said. ‘His perception of time has become damaged in some way.’

‘I can just imagine,’ giggled Rose, ‘how Reg would react if you told him the problem was all in his head. Put it this way, I don’t think you’d see your invention again.’

Waldo had to agree with her on that one. ‘Well then we have no choice but to assume that Reg is sane and that he really has lost his Tuesday.’

‘We? You mean you – this is not my problem, Waldo.’

‘Do you know of any cases of people losing days?’ he asked her.

‘Of course not! What a daft thing to ask!’

Waldo popped a forkful of gravy-and-potato-smeared sausage into his mouth and chewed thoughtfully. ‘Well, perhaps we could go to the library during afternoon break and take a look?’

‘Do you think I haven’t got better things to do than waste my time with this ridiculous nonsense?’

‘So, I’ll meet you there at 3.30 then?’

One thing Waldo had learned about Rose: she was negative about absolutely everything – but her negativity had shades that, with practice, could be interpreted to mean different things. When she began a sentence with the words ‘Do you think I haven’t got better things to do than…’ it generally meant ‘okay, let’s do it’.

Rose finished her water and stood up. ‘You’d better not be late, Waldo Stubbs, or I’ll never forgive you.’

Waldo arrived breathless at the library at twenty to four. Even from behind her reading glasses, Rose’s eyes still managed to burn with a scary amount of disappointment. ‘You’ll lose more than your Tuesday if you keep standing me up like this,’ she whispered icily.

‘Sincere apologies. What have you found?’

She almost threw the book she was reading at him – a collection of odd and curious facts. ‘Nothing very useful,’ she sighed. ‘Apparently John Lennon claimed to have mislaid a weekend in Los Angeles in October 1973. And the entire Christian world lost ten days in October 1582 when Pope Gregory XIII switched everyone over to the new calendar. That one caused rioting in the streets. People thought he’d literally shortened their lives.’

Waldo read the pages she had marked and shook his head. ‘I don’t think we can blame the pope for stealing Reg Fathom’s Tuesday.’

‘And I’m pretty sure John Lennon’s discrepancy had something to do with illegal drugs,’ added Rose.

‘So where does that leave us?’

She pretended to give this some thought. ‘Hmmm… where does that leave us? Try nowhere.’

‘Then it must be time,’ said Waldo ponderously, ‘for us to consult Dr Jenison.’

‘Not Dr Jenison,’ wailed Rose. ‘No! Please!’

Dr Phidias Jenison was, by some distance, the oldest teacher at Cherry Tree. He had been teaching history there almost since the time before there was any history to teach. No one knew how long he had been there. Even old Mr Wragge, the caretaker, who had been at Cherry Tree for at least 25 years, claimed that Jenison predated him. And the odd thing was, as he once remarked to Waldo, Jenison looked just as old then as he did today.

Perhaps because of his age, Jenison could be a bit slow. He never got to where he had hoped to get by the time the bell sounded at the end of a lesson, and students usually had to find the extra information they needed from books. This made Jenison unpopular with most people at Cherry Tree – although not with Waldo. There was something about his plodding manner that Waldo found most relaxing. It was like a kind of soothing music. Waldo had even secretly recorded one of Jenison’s lessons and he regularly played it on his iPod while he worked in his lab. He found it aided his thought processes.

They discovered Dr Jenison in his usual classroom writing something on the blackboard. He was a tall, stooping man with thinning grey hair, a face like shrivelled prune and eyes that always seemed to be searching for something in the distance. He was sucking at a pipe, even though smoking was strictly forbidden in the school. Jenison came from a time long before smoking bans, and Waldo sometimes fancied he still existed in that time, in a little time bubble of his own, safely immune from the rules and regulations of the present day.

Waldo explained the problem without mentioning Reg by name.

‘Lost what?’ muttered Jenison.

‘His Tuesday, sir?’

‘His Tuesday. Hmmm.’ Jenison took some gentle puffs on his pipe. ‘Before you can find anything, my boy, you have to be certain it exists in the first place. Are you sure your friend ever had a Tuesday to begin with?’

Rose looked across at Waldo and made a face that said, ‘why are we talking to this old buffoon?’

‘He definitely had a Tuesday, sir,’ said Waldo, but Jenison didn’t hear him.

‘If we assume,’ continued the old man, ‘that the boy once had a Tuesday – which I think we safely can – this leads us to conclude that it must still exist somewhere and that it has merely been mislaid, waiting – perhaps even hoping – to be found. After all, it may be that Tuesday did not willingly abandon the boy at all. It may be that the boy himself wished his Tuesday away. Now I can understand a person wishing to lose his Monday. Monday is, by common consent, the most depressing day of the week. If I had my way, it would be banned. But Tuesday? Tuesday strikes me as a pretty inoffensive day. It isn’t at the start or the end of the week, or even in the middle. I don’t see why a person would love his Tuesday, but then neither can I imagine why anyone would have cause to truly hate it… In my humble opinion, your friend left his Tuesday somewhere, perhaps while he was thinking of something else. I know I’ve done it. We’ve all done it from time to time.’

Rose put her head in her hands. She looked on the verge of laughing or crying – Waldo couldn’t tell which.

‘So where do you think he should look for it, sir?’ asked Waldo.

‘I think it’s more a case of when should he look for it,’ Jenison replied. ‘And the answer to that is quite straightforward: he should look for it on a Tuesday. If he can find himself on Tuesday, then bingo: the case is solved.’

This was too much for Rose. ‘But sir,’ she cried. ‘How can he find himself on a Tuesday if he doesn’t have a Tuesday to find himself on?’

‘What’s that you say?’ said Jenison.

‘Wait,’ said Waldo. ‘Sir has a point. The boy may not be able to find himself on a Tuesday, but someone else could. If I, for example, managed to find this boy on a Tuesday, that would solve it.’

‘Bingo,’ muttered Jenison, who was engaged in some emergency puffwork on his dying pipe.

The following Tuesday, Waldo went to school feeling confident. All he had to do was find Reg, then all would be well. The day didn’t start too brilliantly. Waldo was jostled by some boys as he got off the bus. His glasses fell on the kerb and were promptly stepped on by another boy. The frame was dented and the lens cracked. He would have to survive the day half-blind. Worse still, Rose had chosen this of all days to absent herself with flu. Waldo would have to manage alone.

He tried to spot Reg during English, the first class of the day, but most of the classroom, beyond the desks immediately around him, was a foggy blur. He listened out for his name during registration. When Mr Finch called Reg’s name during registration a voice answered from near the back of the room. It sounded like Reg’s voice, though it had a slightly odd, echoey quality, as if it had emerged from deep, damp tunnel. Waldo shivered. Had Reg been taken over by a shape-shifting amphibian? No one else seemed to notice, least of all Mr Finch.

During morning break, Waldo toured the library, the canteen and the internet café, but Reg was nowhere to be found. He tried the sixth form common room. Gary Masterson, Chad Wilkins and Rowena Styles – all established members of Reg’s circle – were chatting quietly in one corner. Nervously, he approached them and asked if they had seen Reg anywhere. They looked him up and down as if examining a frog for dissection during a biology practical. Waldo could tell they were trying to figure out (a) who he was and (b) why he would be asking about Reg.

‘You’re Waldo Stubbs, aren’t you?’ said Chad Wilkins finally. ‘The bloke who found my tennis racquet.’

‘That’s right,’ said Waldo.

‘What do you want with Reg?’

‘Mr Brooks wants to see him,’ Waldo bluffed. ‘I’ve been asked to find him.’

‘Haven’t seen him,’ said Gary Masterson. ‘Have you tried the Sports Hall? That’s usually where he is.’

‘Thanks. I’ll give it a go.’ Waldo blushed to see Rowena still looking at him. He had always found her strikingly pretty and had once even tried writing a poem about her. But he had never actually spoken to her, and couldn’t think of anything to say now.

The sports hall was partly occupied by a Year 8 class. With all their noise and movement, Waldo struggled to take in the scene. He briefly put his damaged glasses on to see things better. Immediately he saw him: his tall, athletic, tracksuited figure was leaning casually against the climbing wall. He was surrounded by a group of boys and girls, talking, grinning, laughing. Reg was in his element.

Waldo skirted the mats where the younger children were running and jumping. He tried to catch Reg’s eye, but the bigger boy was too busy listening to a joke being told by one of his admirers. After the joke was finished and the explosion of laughter had died down, Waldo coughed. Reg looked up and saw him. He gave him a puzzled smile, as if to say ‘yes, can I help you?’

Waldo didn’t expect this. ‘Reg?’ he said.

‘Yes?’

‘It’s Tuesday.’

‘That’s right,’ said Reg, causing laughter from those around him.

‘And you’re here.’

‘Indeed I am,’ said Reg, provoking another wave of hilarity.

Waldo felt more than ever like he’d wondered into a strange land with strange, unfathomable rules. ‘Well then can I have my …’ (he wished he had a name for his device) ‘… my thing back.’

‘What thing would that be?’

Perhaps this was, after all, a cruel and elaborate joke. Reg and the other kids were looking at him expectantly, waiting for him to utter more foolish absurdities. Reg was probably hoping he’d say something like ‘You told me you’d lost your Tuesday,’ because that would be certain to raise another huge laugh at his expense. But Waldo wasn’t going to fall into that trap.

‘Reg,’ he said, ‘can we discuss this somewhere else?’

Reg shrugged his bear-like shoulders. ‘Alright. But I’m still not sure what we’re discussing, apart from the day of the week.’ This was greeted with more sniggers. He peeled away from the wall and moved with animal grace towards the equipment room at the far end of the hall. ‘Come into my office,’ he said.

Waldo followed him into the tiny room, which was piled high with ropes, volleyball nets, mats and many other items of that nature. Reg picked up a barbell and adopted a sporty pose as he began a series of lifts. ‘You’ve got five minutes, friend. I’ve got double maths starting at ten past eleven and I still need to shower.’

‘Look,’ said Waldo. ‘You came to me last Thursday and told me you’d lost your Tuesday. You asked me to find it for you. Don’t you remember?’

‘Nope.’

‘Well then either you’re playing a joke on me, or –’

‘I’m not playing a joke. I really don’t know what you’re going on about.’ Reg changed his pose and began uttering a series of little jerky breaths as he exercised a different set of muscles.

Perhaps Reg really did have a split personality. Waldo decided to take a different approach. ‘Do you remember what you do on other days of the week, apart from Tuesdays?’

‘Not really. I’m a live-for-today sort of bloke’ puffed Reg. ‘The only thing that matters to me is the day it happens to be.’

‘And that day is always Tuesday, right?’

‘If you say so!’

‘Doesn’t it bother you that you only live one day a week?’

‘No, why should it?’

‘Well it bothers you every other day of the week. This whole situation bothers you very much, which is why you came to me for help. Now don’t you think it’s time Tuesday Reg reacquainted himself with Restoftheweek Reg?’

‘Why should I?’

‘He worries about you.’

‘Well I’ll text him or something. Tell him I’m okay – if it means that much to him.’

‘I think it’s more than that. He wants his Tuesdays back.’

‘Well you can tell him from me that’s just greedy. Why should I give up my one and only day. He doesn’t need it. He’s got six days already!’

‘You’ve got to stop thinking of Restoftheweek Reg as a different person. You’re two sides of the same personality. You’ve simply got to find a way of living together at the same time, on a Tuesday, and on every other day of the week. If you don’t, I’ll never get my thing back.’

‘Oh yeah, what’s this thing you keep going on about?’

‘Restoftheweek Reg took something from me – a very precious thing as it happens. He told me that if I didn’t find his Tuesday, he would destroy it.’

An odd change came over Tuesday Reg when he heard this. He had ceased his showy barbell lifts and had sort of slumped to the ground. He no longer looked quite so big and powerful in the chest and shoulders and Waldo couldn’t help noticing he was not actually that flat-tummied either. It was as though his insides, like potatoes in a sack, had reassembled themselves in a much less flattering shape. Tuesday Reg looked at Waldo and his eyes, though as blue as ever, no longer shone with charming self-assurance. Instead, they seemed clouded with doubt.

‘He really did that?’ said Tuesday Reg. ‘He really took something of yours and threatened to destroy it?’

Waldo nodded.

‘This is going too far,’ sighed Tuesday Reg. ‘I should give him back his Tuesdays.’

‘I think it would be better for both of you in the long run,’ said Waldo.

‘Oh, I doubt it would be better for me,’ said Tuesday Reg bitterly. ‘You see, I’m not Reg. I’m Tom, Reg’s twin brother.

Waldo literally jumped when he heard this. Yet as soon as the boy said it, he began to see differences – subtle differences: the deeper, throatier voice, the paler, spottier skin, the lankness of his hair and, of course, the plumper tummy. ‘I never knew Reg had a brother.’

‘Not many people do,’ said Tom. ‘Reg is such a big personality in this school, I’m completely overshadowed by him. Reg likes sport. He’s great at acting and singing and dancing. He tells good jokes. I’m terrible at all those things. The only thing I’m any good at is Chemistry. And being good at Chemistry doesn’t win you many friends at Cherry Tree.’ Waldo saw a tear forming in the corner of Tom’s eye as he continued: ‘I just wanted a chance to see what it was like to be Reg – to be at the centre of things, to be listened to, to be loved. I was only going to do it once. But I enjoyed it so much, I did it again and again. I’m like a plant growing beneath a much bigger one that never gets to see the light. It’s been like that all my life. With Reg out of the way, even for 24 hours, I have a chance to, you know, bloom.’

‘So where is Reg now?’ asked Waldo.

‘He’s tucked up in his wardrobe at home, sleeping peacefully. I stole some drugs from the Chemistry Lab. Every Monday night I slip a harmless cocktail of sedatives into his bedtime drink. The dose is just enough to knock him out till Wednesday morning.’

‘What about your parents? Don’t they notice he’s missing on Tuesdays?’

‘No chance. I’m Reg at home, too.’

‘Well then don’t they miss you?’

Tom gave a sour chuckle. ‘You’re joking. My parents hardly remember I was born most of the time.’

‘And what about school registration?’

‘I answer for both of us. Finchie is usually half asleep when he takes it. He never notices.’

Suddenly Tom grabbed Waldo’s arm. ‘Listen, promise not to tell Reg any of this. I swear I’ll never do it again.’

Waldo promised. Then he gently prised the boy’s fingers off his sleeve and left the room, leaving Tom Fathom – Tuesday Reg – still slumped unhappily on the floor.

The following morning, Waldo told Reg he had found his Tuesday. He reassured him that, as of next week, it would never go missing again. Reg, being the incurious type, did not even bother to ask where it had gone. He was simply overjoyed to have it back. This was lucky, as Waldo had promised Tom that he wouldn’t reveal the truth.

‘Well done Waldo Stubbs,’ said Reg joyfully, clapping Waldo on the back. ‘You have a rare talent. Here.’ He handed back the gadget. Waldo was grateful to see it was undamaged. He returned contentedly to the Physics Lab with a strong sense that this was the end of the matter. Cherry Tree High School was surely a big enough place for Reg and Waldo to coexist without their worlds ever having to collide again. And, indeed, for the next two weeks, Waldo’s life did return to its previous quiet and uneventful rhythm.

Read more of the adventures of Waldo Mars in The Finder.

June 28, 2013

Writing Our Lives

AC Grayling

I was listening to a podcast the other day in which the philosopher A C Grayling was talking about a moment of high anxiety he had in his mid-20s: he was convinced, for various reasons, that he was going to die. He managed to calm his fears with the thought that when you die, all you really lose is the present moment, because the past is gone and the future hasn’t happened yet. As that particular present moment was pretty awful, he didn’t think his death would be such a great loss. But then he thought some more and he realised that the present moment is really a junction point between your past and future selves and as such it’s a lot more significant than it may at first appear.

Every action or inaction is a 'sliding doors' moment,

The roads not taken

This got me thinking about the momentousness of ordinary moments: of how, with every action or inaction, we are indelibly creating our past, and at the same time writing our future – with equally permanent ink. We’re making history, and mapping the course of our lives. What about all those turns we didn’t take on life’s road? What about all the people we might have been? What happened to all those other Alex Woolfs?

Limited time

If we’re lucky, we might live a total of 700,000 hours. 160,000 of those are spent growing up, and 220,000 are spent sleeping, leaving just 320,000 potentially productive hours. How much of that time do we waste, I wonder? I’ve spent too many of my allotted hours watching the tennis at Wimbledon this week. This is not untypical for me, sadly – I’m easily distracted. No one will remember me because I watched Wimbledon. In a few weeks’ time, even I will have forgotten those matches I watched. I could have spent that time crafting a great short story – something that might entertain someone a hundred years from now.

As writers we are like gods playing chess with our characters' lives.

Living through your characters

Speaking of stories, one of the ways in which they’re not like life is that nothing is indelible. Like God you can flit around in the background of your characters’ lives, zipping from past to future, adjusting things as you see fit. Your characters can make the choices and live the lives you want them to. If you really want, you can live vicariously through them. And if you do all that, you would be a very poor writer! If you want your characters to be like real people, then they must make their own choices, and their own mistakes. And they may end up wishing, like we do, that they could have made better decisions, and led better lives.

June 21, 2013

Our daughter Maya

Seven years ago today, our daughter Maya was born. She’s our second child, and a surprise in so many ways. First of all, we weren’t expecting a girl. I know it should have entered our heads as at least one possible outcome of the process of childbirth, but surprisingly it didn’t. None of our child-producing friends or relatives had had girls recently, and it turned out that over the following years none would. Maya is a girl growing up in a world of boys.

We didn’t even have a name for her. For about three weeks Paola and I argued about what to call ‘the baby’, and things were looking bleak until my sister Kelly finally ended the debate by suggesting we call her Maya – a name both of us immediately liked.

We didn’t even have a name for her. For about three weeks Paola and I argued about what to call ‘the baby’, and things were looking bleak until my sister Kelly finally ended the debate by suggesting we call her Maya – a name both of us immediately liked.

Her babyhood and toddlerhood passed off without too much fuss. She seemed extremely ‘girly’, liked clothing that was pink and glittery, animals that were small and furry, and stories featuring mermaids and princesses. Then, about a year ago, she began rejecting most of that, and is now into dark colours, lego, Horrid Henry, witches and snails – though small, furry animals remain popular.

What can I say about my little girl? She has eyes sharper than a magpie: able to spot a tiny insect from across a room, or a missing granny in a crowded shopping centre. She’s an expert party organiser, particularly when it comes to her own birthday parties, which she likes to plan in meticulous detail months in advance.

What can I say about my little girl? She has eyes sharper than a magpie: able to spot a tiny insect from across a room, or a missing granny in a crowded shopping centre. She’s an expert party organiser, particularly when it comes to her own birthday parties, which she likes to plan in meticulous detail months in advance.

She does her own thing – be it art or writing, playing with the gerbils, or setting up a school of stuffed toys. And the evidence of her endless imaginative play is scattered messily all over the house, waiting for me to trip over it.

She’s sensitive. I remember seeing her cry watching King Kong fall off the tall building when I thought she’d be too young to feel such empathy. She’s often hurt by little things her friends say. But she’ll ease the hurt by writing a letter to said friend, explaining to her what she did and asking for an apology. She often writes notes to me, informing me politely yet firmly that I’ve done something wrong.

She’s sensitive. I remember seeing her cry watching King Kong fall off the tall building when I thought she’d be too young to feel such empathy. She’s often hurt by little things her friends say. But she’ll ease the hurt by writing a letter to said friend, explaining to her what she did and asking for an apology. She often writes notes to me, informing me politely yet firmly that I’ve done something wrong.

So far she’s not proved herself a prodigy at school. She’s not the best young pianist, dancer, singer or karate kid who ever lived. And I don’t care. She has qualities I can’t begin to describe, and I have no idea where they came from. She’s her own person.

The biggest surprise, I suppose, is that I’m still surprised by her.

Happy Birthday Maya, my beautiful little girl. I love you, and I’m so so proud of you.

June 14, 2013

Things to do in Cardiff when you’re a children’s author

This week I attended the Cardiff roadshow for Children’s publishers and librarians, hosted by the Reading Agency. I came as a guest of Curious Fox, who published my book Soul Shadows.

This week I attended the Cardiff roadshow for Children’s publishers and librarians, hosted by the Reading Agency. I came as a guest of Curious Fox, who published my book Soul Shadows.

It was my first trip to the wonderful city of Cardiff (an easy two hours train journey from London Paddington). The roadshow was based at the city’s main library, which is enormous and looks like a joy to wander around and lose oneself in. I arrived just before lunch, in time for the last of the publishers’ presentations.

It was my first trip to the wonderful city of Cardiff (an easy two hours train journey from London Paddington). The roadshow was based at the city’s main library, which is enormous and looks like a joy to wander around and lose oneself in. I arrived just before lunch, in time for the last of the publishers’ presentations.

Speed-dating

The afternoon was organised in a kind of ‘speed-dating’ format. Each publisher sat at a table and they were allotted ten-minute chats with each set of librarians. These were strictly timed, and when the bell sounded, the librarians would leave and another group would arrive.

I sat with Clare and Cat from Curious Fox. I think that having me on the ‘panel’ helped, as what CF were doing, apart from advertising their existence to librarians, was offering the prospect of author visits to libraries. I told them a bit about what I’d do on these visits, and the age groups I’m trying to reach. Most of the librarians were from Wales or the West Country, and seemed enthusiastic, as they didn’t often get author visits, but some did say that money could be a problem. (Wales has escaped most of the library cuts affecting England, and are even opening new libraries in some areas – but funding for these sorts of extras still appears to be a problem, at least for certain authorities.)

I sat with Clare and Cat from Curious Fox. I think that having me on the ‘panel’ helped, as what CF were doing, apart from advertising their existence to librarians, was offering the prospect of author visits to libraries. I told them a bit about what I’d do on these visits, and the age groups I’m trying to reach. Most of the librarians were from Wales or the West Country, and seemed enthusiastic, as they didn’t often get author visits, but some did say that money could be a problem. (Wales has escaped most of the library cuts affecting England, and are even opening new libraries in some areas – but funding for these sorts of extras still appears to be a problem, at least for certain authorities.)

Creepy events?

Creepy events?

Clare pointed out that some libraries charge a small entry fee for author visits, which has a counter-intuitive effect of raising interest in the event and attracting larger audiences, as well as enabling libraries to cover basic costs. It was also suggested that we try tying in the event to a themed evening, e.g. Halloween, or the Summer Reading Challenge Creepy House, as Soul Shadows is in the horror genre. If we could bring in ghost story tellers, shadow puppeteers and other attractions, it could certainly increase public interest. We’ll see what transpires…

The Golden Ladder

I’ve been rereading Jenny Wagner’s On Writing Books for Children recently. It was published over 20 years ago, but is full of abundant good sense as relevant today as ever. This is from the final chapter:

‘Whether we like it or not, our society thinks of children as lesser beings – not just smaller than we are but less important; and everything to do with them is thought to be less important, too…. Somewhere the misconception has crept in that children are really an inferior form of adult, to be judged according to how well they fit in with the adult world…. This Golden Ladder view of literature, in which children’s picture books are seen to occupy the bottom rung of the ladder, with junior novels on the next rung, novels for young adults further up, and the nirvana of adult literature at the top, seems to be gaining ground. Subtly it is invading all our opinions on children’s books; now, if we come across a children’s book and it’s funny and also easy to read we relegate it to the lowest secton of the ladder without even looking for literary merit…. To see children’s literature in this way is to ignore what good children’s writers have been doing for the past hundred years: to bring a literature to children that is within their range of abilities, but which sacrifices nothing in the way of literary content.’

Well said!