COVID-19 Can-Do: Three Unorthodox Things We Can Do to Improve Equity and Engagement in Remote Teaching Right Now

I am a K-8 teacher-librarian with the Chicago Public Schools. I went to an online training early on in the COVID-19 outbreak to learn how to produce basic video content in which the instructor said, "just put up your green screen..." Green screen?! Oh, yes, let me go grab that, right behind the shock mount for my boom and my three-point lighting kit. Did I leave that behind the toaster oven?

Though I would say most teachers did the requisite excellent and overly-practiced job of making a silk purse out of a sow's ear this past spring, it's a struggle to have real equity when teachers have varying experience, comfort and training in not only creating content for online instruction but producing it, as well as varying levels of bandwith and access to equipment in their homes (not unlike the students). What, then, outside of mastering the magical mysteries of myriad screens, can we as teachers and instructional leaders do to ensure quality educational experiences for all students in the time of COVID-19?

1. Make your "specials" classes your core curriculum.

The great (if uncertified) teacher Auntie Mame says, "life is a banquet, and some poor suckers are starving to death." How are we setting our academic table? Kids cannot live by bread alone. We have the chance to examine the failures in engagement of the past season and correct them with the classes that are the spice of life.

To that end: we don't need fewer specials during this special time, we need more, more, more. Art. Music. Physical Education. Library. Drama. Technology. Turn it all over, give these teachers and subjects unprecedented leadership and time. Arrange your school's schedule around them, the way you used to schedule math and reading. Last spring, a lot of these classes fell to the wayside to prioritize "core classes" in terror that students should "lose time" to the COVID-19 slide. What if students should drop in academic achievement? Insert pearl-clutch here. The worst that could happen by reversing curricular priorities is that students will do as poorly as everyone expects on standardized tests for a year or two. The best: the discovery of passions. Lifelong learning.

And you should expect the best. The approaches of these "special" classes necessitate quick engagement and transitions and are often project-based, exactly what students need during crisis learning. This is where the children will move, explore off-screen, create. This is where there is room to be developmentally appropriate while we have kids looking at screens too much of the day. These "specials" teachers are used to seeing every kid in the school over a period of years, and can integrate the hell out of whatever you're teaching, just tell them...and trust them.

Examine your biases about these subjects and let them go. "Specials" can't be relegated to extras, incidentals, prep periods any longer. The stringency of subject areas defined a century ago needs to die. Invent some new special classes that would be exciting to try online: environmental education, media literacy, armchair travel geography, film history! Bring back home economics, foreign languages and shop class! If you don't have special classes at your school, enlist teachers to integrate these subjects into the core (some already do).

Exuberance aside: this is not a minor detail in terms of creating educational equity. You think families in rich suburban schools and private schools consider art or music or a library an "extra?" Parents with resources are engaging their children in wonderful online pay-to-play opportunities like Outschool (to their credit, Outschool offered scholarships and reduced rates during the initial outbreak). People who want to give their children an advantage know the edge that "specials" deliver. While everyone's heads are turned by the distractions of disaster, up the equity ante for the underserved by being seriously extra in your curriculum.

2. Turn to children's books.

I have said and written that access to children's trade literature (the kind of books found in libraries and bookstores) coupled with the best practice of read-aloud is our best hope for equalizing education in America. Why? Because a great book in the hands of a literate poor child is the same great book in the hands of a literate rich child. Access to books has been proven to be as important an indicator as parent's educational level in determining a student's chances for academic success. I wrote a whole book about becoming a supporting character in a child's reading life story, and to ensure that if schools fail, your children don't have to. You can access it for free here, and scroll through over a decade of children's book recommendations here.

I have also written in a preface to one of my annual lists of book recommendations for children:

Books in thoughtful combination are an education in themselves...I can only imagine how a child who experiences these titles will be changed, and change is the definition of learning. Through what new lenses will the child view the world after experiencing this art? What biographies will inspire them, what mentors will fly through space and time to scaffold their dreams and efforts? How will they view and understand the natural world? What new friends will they find inside books that will inform them to know how to connect and empathize with people outside of books? What will make them laugh, cry, think?Not to mention, a child who discovers the magic of reading will never be as lonely or bored as the child who has not. That meant a lot on an average day. During quarantine, it means even more.

Let's take a moment to talk books. Are they all created equal? The crisis has led many teachers and students, understandably and necessarily, to turn to digital resources including ebooks. However, studies have shown that readers of printed books have a cognitive developmental advantage over readers of e-books. That means children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds relegated to free school e-book collections alone may be getting a separate but equal reading opportunity.

One thing we can do as a country to promote access to print books for all would be to insist that catalogs, in order to be eligible for bulk rate through the U.S. Post Office, contain a certain percentage of pages dedicated to reading material at the end of them, at least through the course of this pandemic. Graphic novels, serials, classics...can you imagine how children would hop up and down at the arrival of the Pottery Barn catalog if a few pages of a Raina Telgemeier or Dog Man were attached? This will ensure that all children with an address have access to reading material. The U.S. Post Office has a long and magnificent history of disseminating necessary information through the mail. This crisis could usher in a new age of appreciation of the agency as it delivers educational equity to children when it is so sorely needed.

For children who do not have an address (unfortunately a demographic predicted to grow in the coming months and years), we must publicly fund Little Free Libraries. Right now, most of these libraries are cute and expensive and privately set up, but they need to be recognizable and ubiquitous, the way we have post office mailboxes.

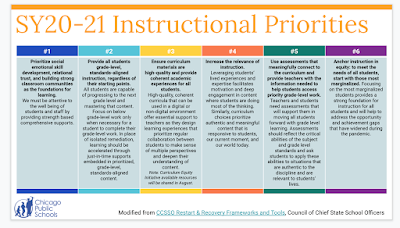

Lastly, look at this plan from the Chicago Public Schools for Instructional Priorities for the 2020-21 school year. Do you know else what they are describing?

They are describing a school library with a program run by a trained school librarian to a T, actually. Yet now, during the COVID-19 outbreak, there are only about 100 librarians in the Chicago Public School system for over 600 schools, i.e. about 100 librarians for over 350,000 students, even though research from 34 state studies suggests undeniable correlation between staffed school libraries and student achievement. That means a system with over 75% economically disadvantaged students, a system with over 80% Black and Hispanic children, have a 1 in 6 chance of having a school librarian. I am calling out my own city, but this is hardly the anomaly in urban areas across the country.

During COVID-19 and in the years of recovery to come, this blatant disparity will only serve to widen the gap of achievement and all of the economic opportunity that it ultimately affords. So I'd hazard to say, if you are advantaged by your race and/or your income and/or your zip code and your child goes to a school with a school librarian, you have work to do outside of putting a sign on your front lawn. Equity in education is part of showing, not telling, that Black Lives Matter, and school libraries are equity in education in action. Advocate loudly for the advantage that school libraries deliver and that some children receive while others do not. If children's books are our best hope for equalizing education, we need the libraries to deliver them.

3. Train parents.

Here's the most common question I heard from shocked, overwhelmed parents when the schools closed in March: "does this count?"

Oh, the panic. How much of this do we have to do? Where do they turn it in? Why is it taking so long to do? If the work is finished early, what are they supposed to do? What if I don't have a job, or childcare, or someone is sick? Is the teacher looking at my messy apartment? What if our computer goes down? What if other children need the computer? What if I need the computer? What if the computer breaks or I can't get a connection? What if I have to be at work and my child runs into a problem on the computer? What if I can't get my child to sit in front of the computer? What if I don't have a computer? How will that affect the grade? Will my child be held back? If it doesn't count for the grade, why should my child do it? The grade, the grade, the grade, icing the towering, dreadful cake is the grade, in the face of, well, death and illness and job loss, here we are, still worried about the grade.

And after responsibly giving attention to the grade in the face of all this, a sense of entitlement may start to creep in, and parents may find themselves frustratingly thwarted by teachers; turns out, working for a long time is not necessarily meeting a standard, busy is not necessarily the same as learning, and every time your child raises a hand or turns something in, it may not result in an "A" (though your child may still be a good and successful person in the long run nonetheless). What counts, then? What counts?

Many parents are terrified, it seems, of failure in a time when it seems all systems are failing; when many of us, as adults, are working without economic or health care safety nets in a time of crisis. Some parents, faced with this high level of necessary involvement, are heavily projecting their own childhood anxieties around school and performance. Completely understandable.

I think we could go far in alleviating a lot of counterproductive stress and direct conflict with teachers if we took more time to clarify expectations. Just as experienced teachers know the first week is when you can really set the tone for the classroom, in the context of COVID, rather than diving into assignments and protocols with the children, the first week might be better spent helping parents to set the tone to support learning in the home, slowly walking through how to log in, how to find assignments, how to communicate with the teachers, how to create a positive physical space in the home conducive to learning, how to juggle the needs of many children in one household with limited computer access. Answering these kind of logistical questions, and making answers available in the home language, will contribute to equity.

There's so much that schools can do to alleviate deeply personal parental insecurities surrounding failure that can result in clashes with children and teachers through a combination of better-communicated understandings, affirmations and real partnership. Letter grades during COVID have already proven intrinsically inequitable because everyone's situation is so different. We can start by underscoring the big, basic, new-to-many idea that participation can "count" and matter even when it is not graded.

Parents are not professional educators, but they are always in a teaching role and always positioned to foster a relationship with the child that can either incite or stifle learning. In the context of claustrophobic COVID, this role is pronounced and overwhelming and parents need extra reassurances and clarification. It is fair to suggest assessments and accommodations may look different during COVID, and parents need to know this.

Just like with the students, if we don't handle climate on the front end, we will all suffer for the rest of the year. So let's take the time to inservice parents like new teachers and give them a leg up by sharing pedagogical insights for survival.

Parents need to learn, as new teachers do, that there are good days and bad days, and that an education is the sum of many parts. One bad day is not the end of the world. Forgive yourself and others and keep going.

As new teachers do, parents need to turn focus from whether they are succeeding to whether the child is succeeding, and accept that some portion of challenge or even failure is often necessary for growth.

As new teachers do, parents need to learn to break tasks down into small steps and be generous and genuine in celebrating steps toward mastery, both to encourage the child and themselves.

They need to see, as new teachers see, that the most effective behavior management comes from engaging children in interests and relevancy, not negative consequences.

As new and effective teachers do, parents need to examine their own enthusiasms and skill sets to determine what they really have to share as human beings and then realize that lifelong learning comes from the relationship implicit in that sharing, not from any worksheet or app divorced from the context of that relationship.

Parents then need to be encouraged to value, without disparagement, what they have to share, whether it's the theory of relativity or long division, or how to enjoy a book, or cooking soup, or finding middle "C" on a piano, or growing flowers, or making change for a dollar, or making a bed, or telling a joke, or braiding hair, or speaking another language, or locating the Big Dipper, or simply how to be brave even when things aren't really going your way.

Most of all, parents need to learn, as teachers invariably do, that if the child doesn't have have mental and physical health, if the child doesn't feel safe, if the child is tired or hungry, it's hard or impossible to deliver any content at all. And if what a parent can do on a given day is take care of these needs, set the expectation that they participate in whatever the teacher has arranged for them as best they can, if they share a book, or even just love them, that's pretty darn okay. That's what counts right now. Maybe it always has been what counted.

This may be the end of the age of fallacies that upheld a status quo. The big assignment now is that we invent ourselves. The children are so bravely growing and doing this work every day, with or without us. Refreshed curriculum that invites art, movement, handiwork, the chance to read and some sanity in their inner circle will go far to support this work, preserve the humanity of the children we serve and keep our influence positive, even in the face of our own trials.

I leave you with a short film that made a big impact on me in imagining a new school year. Thank you, Liv McNeil.

I look forward to knowing what you imagine, in the comments section and elsewhere.

Stay well and happy reading, friends.

Published on August 05, 2020 22:48

No comments have been added yet.

Esmé Raji Codell's Blog

- Esmé Raji Codell's profile

- 148 followers

Esmé Raji Codell isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.