‘Tanks’ for the memories

Like many people, I have fond childhood memories of VW vans, but I suspect mine are a little different than most. For about a year in the early 1970s, my family’s primary transportation was a shared, late-60s-model VW van known as the Penn Tank.

The name referred to the University of Pennsylvania logo on each side. The University’s archaeology department had lent it to the Kyrenia Ship Expedition, a group of American and British nautical archaeologists recovering and reconstructing a 2,300-year-old Greek merchant ship on the northern coast of Cyprus. It earned the “tank” moniker as a tribute to its predecessor, an older, more beleaguered VW van dubbed simply “The Tank” by one of the British members of the team.

I found myself thinking about the Tanks as I read Jill Lepore’s piece in the latest issue of The New Yorker about the new electric version of the VW van that Volkswagen plans to roll out in 2024. The story is largely an ode to the iconic vehicle that Arlo Guthrie referred to as a “microbus.” (VW had to be careful what it called the vehicle. See the part in the article about LBJ, the Chicken War and the resulting legislation that still affects import vehicles.)

I was too young to appreciate the counterculture applications of the VW van, but Lepore noted that in Europe the van “could do anything: it was used as a fire truck, an ambulance, a delivery vehicle, a taxi.” I smirked. It was also used to haul diving equipment for raising ancient shipwrecks.

My father first arrived in Cyprus in mid-1971 with the hope of reassembling some 6,000 pieces of the Kyrenia Ships ancient hull fragments that had been sitting on the sea floor for more than two millennia. He had only the vaguest ideas of how to approach the project. No one had ever attempted anything like it.

He was greeted by two members of the expedition driving the faded green-and-white Tank. It had a tiny rear window, and both panels of the split windshield, inexplicably, opened outward so you could drive with the windshield up, breeze and bugs blowing in your face. The Tank was already about 15 years old by then, and the back seats had been removed to make room for air tanks, regulators and other equipment used for diving on the wreck site. In honor of my dad’s arrival, the team found an upholstered chair and put it in the back for my father to sit in for the 30-minute ride to Kyrenia. The Tank broke down three times on the way back, the last time as it topped the Kyrenia Mountains. They coasted into town.

By comparison, the Penn Tank, which arrived a year or so later from a land dig — in Afghanistan? Iran? — was pure luxury. It was much newer — larger rear window and while the windshield was still split, it didn’t open. Because my father was the only member of the expedition with children, we were allowed to use the Penn Tank as our family car. It was an American vehicle, with the steering on the left. In Cyprus, as a former British colony, everyone drove on the left. Every trip was an adventure.

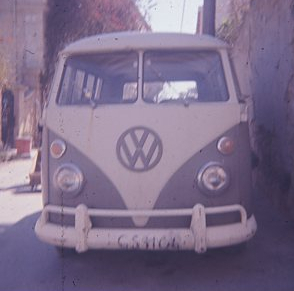

The Penn Tank

The Penn TankAnd while the Penn Tank was an upgrade from its predecessor, it was still a work vehicle, pressed into service in hauling diving gear, carpentry or welding supplies, anything that was needed. My mother recalled that she and my father had to drive it to a fancy dinner at the American embassy in Nicosia. She put a towel on the seat so she wouldn’t get her dress dirty, and they parked three blocks away, figuring the valet at the embassy would never believe they had an invitation.

The Kyrenia Ship was being preserved and rebuilt in a harbor side castle, most of which was built by Richard the Lionheart enroute to the Holy Land during the Third Crusade. After the last of the Kyrenia Ship’s hull fragments moved from fresh water to tanks of polyethylene glycol (the next step in the conservation process), we needed to demolish the large freshwater pool the wood had been soaking. My father would use the space to start reassembling the hull. But before we did, we decided to have a pool party. Everyone in the expedition donned bathing suits and piled into the Tanks with beach balls, rafts and brightly colored towels. We then drove in tandem across the narrow bridge and into the castle. Tourists gaped in confusion. It was the closest the expedition workhorses came to the sort of hippie moments that people statesside associate with the VW van.

Kyrenia was a small town, and we walked most places. But sometimes, my father would take the Penn Tank to the castle before we embarked on another errand. Parked in the courtyard, outside the “ship room,” I would pretend to drive, turning the massive steering wheel, fiddling with the turn signals, even once pulling it out of gear without using (or knowing about) the clutch. We covered a lot of ground my imagination, the Penn Tank and me, while waiting on my dad to tear himself away from his beloved ship.

The Penn Tank ultimately made its way to another dig in Turkey, and later, one of my father’s associates used it to flee Beirut with his family after civil war erupted in 1975. As for The Tank, it, too, found itself in a war zone. In the summer of 1974, my dad drove The Tank to the airport in Nicosia, then flew to Turkey for what should have been a weeklong trip. War erupted soon after he left. He wound up coming back to the U.S.

Another member of the expedition made his way back into Cyprus after the hostilities, and eventually to the airport in Nicosia. The airport had taken heavy shelling, and the parking lot was full of burned-out vehicles. Nestled among them, seemingly untouched, was The Tank. The tires are deflated, but with a few shots of air from a bicycle pump, The Tank once again putt-putted its way over the Kyrenia Mountains and back into town.

No one knows what happened to it after that. There are rumors it was spotted being driven around town, others say it was last seen near the harbor. I prefer to think of it atop the Kyrenia Mountains, lingering a moment before it begins to gather momentum and heads for the sea.