Medieval Castles: A Complete Guide

Medieval castles are some of the most iconic structures to ever have been created. With their walls of thick stone, looming towers and threatening gates, castles were designed to keep out unwanted guests in a period filled with conflict and fighting.

In this guide, you can find a comprehensive look at medieval castles, starting from the early structures using in the early Middle Ages right through to the great stone structures we see in the later medieval era.

You can also find details on what life was like for those inside the castle walls.

Jump to the section you’re most interested in by using the table below:

ContentsA Brief History Of CastlesWhat Was Life Like In A Castle?What Type Of Servants Did They Have In A Castle?Glossary Of Castle Features And FortificationsEarly FortificationsCastle TowersGatehouses, Moats, and DrawbridgesWallsBattlementsWhat Was It Like Inside The Walls Of A Medieval Castle?A Brief History Of CastlesThe Middles Ages lasted about a thousand years, kicking off in or around the 5th century and lasting until the 15th. It can be split into two periods: the ‘Dark Ages’, which ran from the 5th to 10th century, and the High Middle Ages, from the 10th to 15th. (I understand the phrase Dark Ages is no longer accepted by some, but for ease, it’ll serve here).

Castles didn’t exist in the Dark Ages. What did exist were the remains of Roman fortifications, but only in Western Europe. Everywhere else structures were made from wood.

Then the High Middle Ages came about and so too “The Age of Castles.” You couldn’t move for a castle in Europe. There were so many that no historian has been able to comprehensively document them all. Castles were status symbols, a means for the nobility to challenge their king, and incredibly, many continue to exist today.

But as the use of castles grew, so too did methods to try and take them down. With the advancement in weapons like catapults, trebuchets and cannons, castle walls were abandoned and open-field warfare was once more adopted.

One thing that didn’t change over time, however, was the lives of people who lived within those solid, windowless structures. They were often cold and damp, with tapestries hung on walls to keep the chill at bay. And with only arrow loops for windows in many castles, they were very dark. That meant lots of fires burning which wasn’t good for respiratory health.

Click Here To Learn More About Worldbuilding In Fantasy

What Was Life Like In A Castle?The medieval castle was built for protection and safety, but also for comfort and luxury. The stone walls, the turrets, the moat, and the drawbridge are all there to protect the people inside from invaders.

But they’re also designed to be dense and warm, as well as a visible statement of power and wealth.

Knights and lords lived in these castles as well as their servants and families. These aristocrats would have been trained at a young age to fight wars on behalf of their king. Such training would have involved being taught how to ride horses, use weapons, hunt animals, and manage their estate.

The lord and his family spent most of their time in the Great Hall, which is the largest room of the castle. The rest of the people who lived in the castle, like servants, would have had smaller rooms.

Knowing this structure and what day-to-day life was like here can help you come up with ideas when designing your own medieval castle. For example, you could create a unique space for your servants to live, maybe one that’s brutal and foul.

Click Here To Learn More About The Life Of A Medieval Lord

Click Here To Learn More About The Lives of Women In The Middle Ages

What Type Of Servants Did They Have In A Castle?As we’ve just seen, it wasn’t just lords living in a castle. Depending on the size of the household, there could have been hundreds of support staff working there too. When it comes to writing stories, knowing about these different roles can help you find inspiration for characters, as well as make your worldbuilding more immersive.

So what types of servants did they have in a castle?

Medieval castles had a variety of servants, including butlers, cooks, chambermaids, valets, stable hands, and grooms. There were also guards, sentries, and soldiers who protected the castle and its inhabitants. Many of these servants were lower-class individuals who lived and worked within the castle walls. Some were also skilled craftsmen such as blacksmiths, carpenters, and masons.

The number of household staff depended on the castle and its purpose. Some castles were residences so had a large number of domestic staff, such as cooks, chambermaids, and valets. Others had a larger number of guards and soldiers, particularly if their purpose was for defence.

In general, the larger and more important the castle, the more people would be required to maintain and operate it.

Glossary Of Castle Features And FortificationsBefore we hack our way further into this fantasy writing guide, it’d be useful to have a rundown of some of the different types of fortifications:

Castle: a fortification of the High Middle Ages, characterised by high walls with towers and usually a moat. Served both residential and/or administrative purposes. Fort: a small strongpoint occupied by military personnel.Citadel: a word used to refer to either a castle or a fortified section within a city similar to a castle in size.Fortress: also referred to as a fortified city or town, it has many features in common with a castle, such as high walls, gatehouses, and battlements, though much larger, housing a populace.Motte and bailey: consisted of a tower standing upon a man-made mound, also known as a motte. This motte was located within a courtyard known as a bailey and encircled by a fence of wooden stakes (also known as a palisade) with a fortified gate.Donjon: a great tower or innermost keep of a castle. The term donjon was later replaced with keep.Rampart: a defensive wall of a castle or walled city, having a broad top with a walkway and typically a stone parapet.Portcullis: a strong, heavy grating that can be lowered into grooves in the ground. Usually found in gatehouses.In addition to these main types of fortification, there were tower houses, observation posts, and fortified churches and monasteries. These kinds of terms can be of great use when describing your own medieval castle in your stories.

Early FortificationsCastles evolved out of early, cruder fortifications, three in particular: the gród, the bergfried, and the motte and bailey.

The gród was a simple, circular fortification that consisted of an earthen rampart with wooden walls, a fortified gate, and sometimes a moat.

The bergfried was a tower, used as a lookout and later as a residence. Before the 13th century, they were mostly made of wood. Entrances to bergfrieds were found on the first floor instead of the ground floor. The reason? Bergfrieds and keeps tended to serve as the last point of defence and having it a floor higher made it more difficult for the enemy to take it.

The motte and bailey consisted of a wooden tower standing upon a man-made mound, also known as a motte. The motte was located within a courtyard known as a bailey, which itself was encircled by a fence of wooden stakes (also known as a palisade), with a fortified gate. It was a popular fortification with the Vikings. In the image below, the bailey is the lower level, the motte the upper.

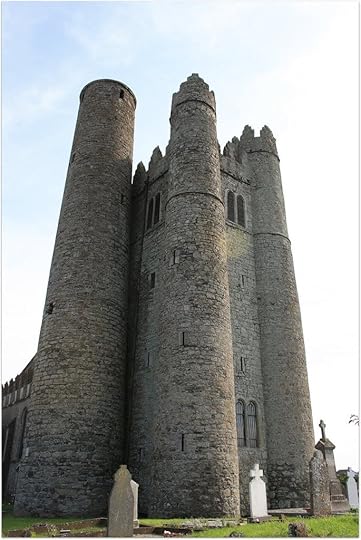

Castle TowersTowers played an integral role in the defence of a fortification. When constructed as part of the wall, they jutted forward to allow for flanking fire. They were also constructed separately. In the early years, they were made from wood, later, stone.

In most instances towers were placed at corners but were also added at intervals, sometimes at set distances, others random. It all depended on the terrain, available resources, and the skill of the builder. These factors also influenced the height of a tower.

A clever feature seen in some towers was an open back. Not only did it allow for supplies to easily be hauled up, but if attackers overran that tower, they couldn’t use it against the defenders. Some towers were cut off from the wall by drawbridges for added defence.

One vulnerability of towers was mining. Early towers were square in shape, but the dead angles made them vulnerable to mining attacks. In the 12th century, more circular or semi-circular towers were introduced. This was a risk the Romans were already aware of is why many Roman fortifications had D-shaped towers.

When it comes to writing about a medieval castle, especially one which is involved in combat, towers will likely feature heavily. They’re a target for attackers and a prominent defensive structure for defenders.

Gatehouses, Moats, and Drawbridges

Gatehouses, Moats, and DrawbridgesThe gatehouse is perhaps the most eye-catching feature of a castle’s defensive fortifications. And many a medieval castle has featured them.

The gate was perhaps the most important feature of a fortification because, in theory, it was the easiest point of access for attackers. Most gatehouses had battlements that defenders could stand upon to keep attackers at bay. Moats and drawbridges were added later to enhance defence.

Gatehouses consisted of a set of reinforced wooden and/or metal doors and a portcullis made of reinforced wood or iron. An example of a mighty gatehouse can be seen in Harlech Castle in Wales. It had three portcullises, three doors, and four towers. If you managed to get past the first you were trapped at the second, and so on. The walls of the gatehouse were punctuated with arrow slits through which the defenders could fire upon the attackers, and murder holes in the ceiling through which arrows could be fired, rocks dropped or hot liquids poured.

One simple yet effective feature of gates was to place them at an angle instead of facing outwards. The purpose was to prevent battering rams from having a clear charge. Another feature designed with this in mind was the barbican, which was an outcropping of wall in front of the gatehouse.

Drawbridges were basic in construction, raised by chains and winches. They went hand in hand with moats, so if there was no moat, there was no drawbridge. The moat is one of the oldest features of fortifications. Simply put, it was a ditch surrounding the castle or keep. Rivers, lakes, ponds, or swamps were used to fill in moats, others were dry.

A moat had to be deep enough to prevent an attacker from wading through it and wide enough to stop someone from leaping across. Around 3 meters, or 9 feet, was the average depth before the 11th century. After that, they grew much deeper. The size of the moat, however, depended on the terrain and how easily it could be excavated.

Moats were also reinforced with other obstructions, such as sharp stakes along the bottom or inner wall. A deep moat is also protected against the threat of mining.

One thing about moats to keep in mind is that they tended to be disgusting. Excrement and waste from the fortification were tossed into the water, turning them into cesspools. It was the job of the peasantry to clean it up, on average twice per year. Peasants are always left with the worst jobs, aren’t they?

WallsThe phrase enceinte is the technical term for the walls and towers that encircled a fortification (it’s also an archaic word for pregnant, so careful not to confuse the two!). The walls were also referred to as curtain walls.

Walls developed significantly during the Middle Ages. One of the earliest types of wall was a dense structure made of earth and wood. Timber walls soon replaced these, though they were thin, vulnerable to fire, and over time, decayed. The solution to such problems came in the form of stone walls, though early stone walls were pretty thin.

The Roman method of building walls was much superior. They built two walls with a space in between which they filled with rubble. Despite Roman walls surviving into the Middle Ages, nobody thought to copy them. Arrogance, perhaps? Maybe ignorance?

So how big were walls? It’s hard to say. Few records were kept of the constructions of walls, so what’s known today is the result of archaeology and guestimates. We can turn again to the Romans who had a pretty good system for making walls. For every one meter of height, there had to be 0.25 meters width. So, for example, a wall 6 meters high would be 1.5 meters thick. But it all depended on how thick the walls needed to be. Vulnerable sections of wall were built the thickest, whereas those upon favourable terrains, such as hills, were thinner.

Towers became a staple feature of walls, ranging in height from 10 meters to as tall as 37 meters. Toward the end of the Middles Ages, the height of some walls was raised to the height of towers. Staircases inside towers and battlements turned clockwise to allow for the defenders to fight with their right hand and restricting the swing of any attacker.

Keeps were pretty imposing too, and over the years grew in size. Large keeps were 20 to 30 meters by 15 to 25 meters, with walls 2 to 4 meters thick. The castle at Coucy, France is particularly large, and in Angers, France, there lies another immense fort. The French got carried away a bit, it seemed.

Battlements

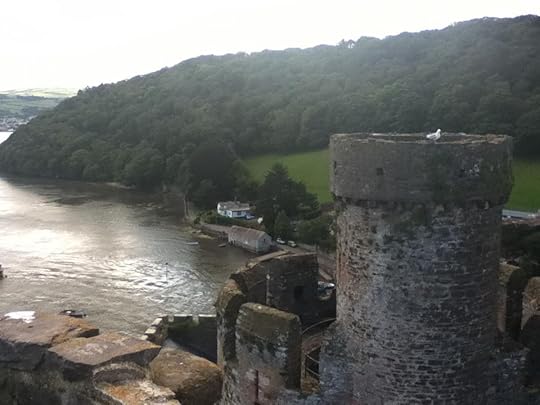

BattlementsThe term battlement refers to the upper part of a wall. During the Middle Ages, they usually featured crenels (an indentation in the battlements), embrasures (an opening in a wall or parapet) and merlons (the solid part of a crenellated parapet between two embrasures).

A picture I took at Conwy Castle, Wales. At the bottom, next to the tower, you can see examples of merlons.

Melons were not always rectangular in shape. In time they became more decorative, the style influenced by region and culture. In the Middle-East for example, the shape of merlons was influenced by Islam.

The space in between the merlons sometimes featured shutters to provide extra protection. This did, however, restrict the archer’s range of fire to what was beneath them. As the skills of masons developed, such shutters became redundant. Instead, slits were carved into the stone, known as an arrow loop, through which arrows could be fired. At first, they were thin, restricting the scope of fire to one direction, but they developed with time with wedge-shaped variations developed. This restricted the archer’s view to what was beneath them but reduced the scope of vulnerability. A cross-shaped loop was developed too which allowed for sight left and right. A feature called an oillet, which is a small circular observation hole, was also added.

Here’s me at Conwy Castle, Wales, re-enacting a defender. And to the right is an example of an arrow loop.

Behind the crenels was the wall walk, also known as an allure. In some castles they were built into the walls, in others they were wooden, supported by beams. Towers, which often were incorporated into the battlements, also had allures, giving defenders greater height with which to observe the battle and target threats. Towers with no allures had roofs of slate or lead, conical in shape.

To get up and down the allures two options were preferred: the bog standard ladder, and a stairway within a wall tower. The latter was more effective defensively. If attackers swarmed upon the walls, they were trapped there, exposed, unless they managed to take a tower.

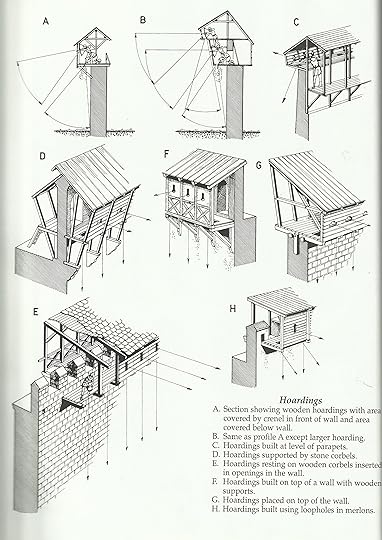

To aid the defenders further, in or around the 12th century a feature known as hoardings was introduced. They were wooden structures which projected out over the wall, sort of like scaffolding. How did they do this, you wonder? During the construction of the battlements, slots or holes were added to allow for beams to be fitted. They were vulnerable to fire, but to counter this their roofs were covered with wet hide.

Image is taken from ‘The Medieval Fortress’ by J.E. Kaufmann & H.W. Kaufmann.

As you can see in the above drawing, the range of fire is much greater upon the hoardings. Rocks and scorching liquids could be dropped on the attackers below. Some walls featured a plinth at the bottom, which was a section of wall which jutted outwards. Rocks bounced off of these plinths and into attackers, extending their effectiveness.

Hoardings were later incorporated into the walls. Parapets, supported by arches, were moved forward to hang over the walls and in that additional space something called a machicolation was introduced: essentially a hole in the floor.

Windows were a rare feature on towers and walls and even keeps. They were seen as weak points. Only the residential towers or keeps had windows, which were made from glass, normal or stained, or just iron bars (glass was expensive).

What Was It Like Inside The Walls Of A Medieval Castle?

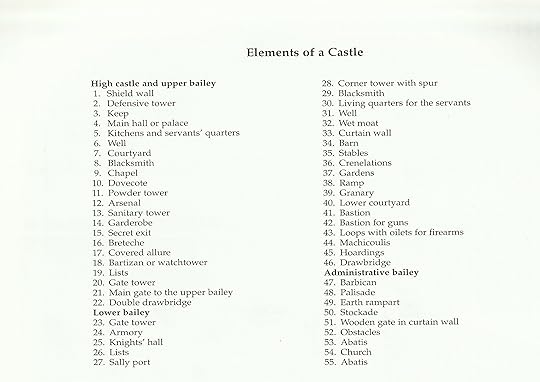

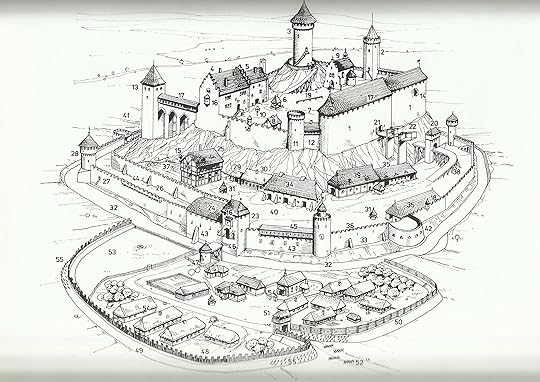

Image is taken from ‘The Medieval Fortress’ by J.E. Kaufmann & H.W. Kaufmann.

What did the defenders need to sustain a siege? An important feature was wells. Rainwater could be gathered too, but without a supply of water, defenders couldn’t last long. Water was also vital to helping douse any fires caused by attacks.

Residential areas were usually found in a keep or tower. Inside was a great hall or banqueting room, bedrooms, garderobe (toilet), storage rooms, and so on. The kitchen was kept separate due to the risk of fire.

A classic feature of the great hall is a huge hearth. It wasn’t until the 14th century that chimneys were introduced, so up until that time people were exposed to toxic fumes.

Hearth at Tattershall Castle, London

Walls were decorated with tapestries, which provided a mild degree of insulation. With few windows, illumination came from torches held in sconces and candles.

The courtyard, or bailey, was the main open area within a castle. Some larger castles had more than one courtyard. Other buildings you’d find within a castle were a chapel, stables, and barracks. Castles did not have dungeons during the Middle Ages. Prisoners were kept in towers; only in the Renaissance period were prisoners moved to the pits of the castle.

The post Medieval Castles: A Complete Guide appeared first on Richie Billing - Writing Tips And Fantasy Books.