Collecting Scars

I think life is a process of collecting scars.

Mine are inconsequential, all things considered. The oldest ones are the marks from immunizations: smallpox on one arm, tuberculosis on the other. If you were born in the United States, you won’t have these. But when I was a child, in socialist Hungary, we were still being immunized against Victorian-era diseases. So I have a round scar on one arm the size of a five-forint piece, a smaller round scar on the other. There is the small round scar near one eye from having chicken pox, and the small straight scar near the other eye from a rowdy-boys-during-gym accident in high school. After I got that one, I was wheeled through the school in a wheelchair with blood flowing down my face. I felt quite injured and fancy! When my mother looked at it, she said, “Oh, that’s nothing. Wounds like that always bleed a lot.” Then she put a few butterfly steri-strips over it, and that was that.

Then there are my two appendectomy scars from graduate school. I suppose they mark where the video camera and surgical tools went in. I can barely see them now. And then there is the scar from the thyroid lobectomy in May. That’s the largest and most prominent, of course. I still don’t know how I feel about it. Perhaps I will feel differently when the internal scar tissue is not so palpable. Right now, four months after the surgery, it still feels like I have a rubber eraser in my neck. I’m still using scar gel and SPF 50, still doing scar massage, the way they demonstrate in the YouTube videos. I feel very lucky that there have only been two serious problems with my health so far — appendicitis and recurring nodules on my thyroid — and that they are very common problems to have. All in all, I’ve spent very little time in hospitals.

Nevertheless, I think life is a process of collecting scars. They don’t go away, not fully — they are like marks on the map of your body, showing where you’ve been, what you’ve experienced. Time writes your history on your skin, just as you might write it in a journal. Except, of course, that time’s journal is public. You can see the scar on my neck, although it’s slowly fading. And when you see it, you might ask yourself (if you’re too polite to ask me), What happened there?

But I was thinking too of the scars that are not written on our skin, the scars that are inside, that affect our hearts and minds. Life is a process of being wounded, healing, but then feeling the scar left behind — because I think there is always a scar left behind. From each hurt, each loss, each failure. And then it’s a process of waiting as we heal, of trying to help the healing process. The first medicine for my surgical scar was oxycodone. For heartbreak, the first medicine might be hours of watching Netflix, which would have a similarly numbing effect. Instead of applying scar gel, you might apply ice cream where it hurts. Or music. Or long walks. Or, of course, therapy.

I suppose it depends on the depth of the wound, the extent of the scar. For some wounds, the process of healing is long, and the resulting scar can limit your mobility, your flexibility — this is as true for mental and emotional scars as physical ones. I don’t know what the process of scar massage might feel like for these internal scars. I’m not a therapist. But there must be one — there must be a way of dealing with them so they hurt more in the short term, but less in the long term. Hopefully, if I’m diligent about the massage part of my therapy, the rubber eraser in my neck will eventually go away, and I won’t feel it each time I swallow.

So I guess I don’t really have any wisdom here, because scars aren’t exactly beautiful, and saying that everyone becomes scarred is not an optimistic statement. The scars fade, but never completely. But I’m not trying to say something wise or optimistic. Rather, I’m trying to say something about how I’m experiencing life right now, which is as a relentless march of time that marks you as it passes. And yet, and yet, we also write on paper, and that is as valid as what time writes on our bodies.

Perhaps it is the way we respond to how time scars us. Perhaps the marks we make on paper are the way we take time’s power into our own hands, make our marks against time. We say, “You may scar my body, but look — these words will outlast me.” Whether on clay or papyrus or parchment, we have been doing this since writing began. And now here I am, doing it on a computer screen, writing, “I think life is a process of collecting scars.” And perhaps, just perhaps, if these words are shared and copied and remembered, they may outlast my physical body. Or other words of mine may be the ones that last, who knows? And so, I continue to collect scars and make my marks on the computer screen, as I am doing now.

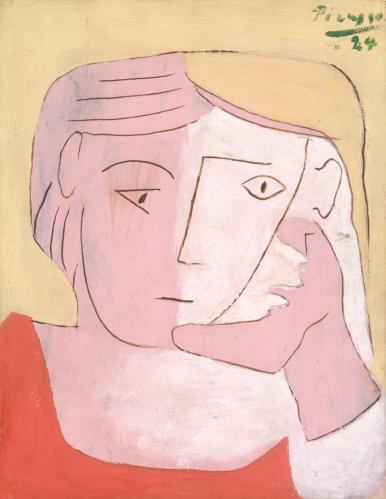

(The image is Head of a Woman by Pablo Picasso.)