Nothing is Wasted

Sometimes I get mad at myself for wasting time.

I have wasted time in the most ridiculous ways. I’ve watched YouTube videos on the history of ballet pointe shoes. I’ve watched Saturday Night Live skits about bridesmaids, and motivational speakers who talk about the need for a bedtime routine, and kittens being rescued in various ways. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a good and worthwhile thing to rescue kittens and have a bedtime routine. But there’s no need to watch videos about those things. I’ve read articles on decorating cottages in the Cotswolds and opinions pieces about the latest political shenanigans in Congress.

None of these things have helped me in obvious ways, so it’s easy to say they are a waste of time. Why do I watch or read them? I tried to think about why — boredom? Addiction to my phone? But the most obvious answer seemed to be curiosity. I saw a kitten in a drainpipe, and I wanted to know what happened to it. The ballerina showed me a pair of pointe shoes, and I wanted to know why. I saw a picture of the cottage, and wanted to know who had moved into it and why it had been painted that particular shade of green.

I am addicted to something, but it’s not my phone, or social media, or the news. What I’m addicted to is stories. With equal attention, I will watch a kitten rescue video or read an article in The Atlantic or start on a novel. And I will turn from one to another, or intersperse them — yes, I can watch an SLN skit on bridesmaid karaoke and then turn to a novel by Isabel Allende. One is serious literature, the other is — well, it’s sort of mental fast food, like french fries for the mind. And yet, I want to make an argument here about what it means to waste time as a writer.

What I want to argue is that . . . nothing is really a waste of time. In “The Art of Fiction,” Henry James wrote, “Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost.” These are the things that should not be lost on you when you’re, for example, watching a kitten rescue video:

What kind of kitten is it? Is it a black kitten with a white nose? How large is it? How large is the drainpipe? How did the kitten and drainpipe come to inhabit contiguous spaces?Who is rescuing it? What sort of voice do they have? What are they videotaping? Can you see their hands? Their feet? What techniques are they using to lure the kitten — the tried and true tuna method? Something else?What will the subsequent story of the kitten be? Will they adopt it? Foster it? Is it going to a shelter? If there is a happy ending to this story (and there almost invariably is), what is that happy ending?What storytelling techniques is the videographer using? What is the beginning, middle, and end? Are you in suspense? Is there music added? How are your emotions being affected and possibly even manipulated?Who are you, lying on the sofa watching the kitten rescue video? Are you doing it because you’re tired? Bored? Desperately in need of reassurance that this is a world in which kittens are rescued?All of those things are elements of story. All of them are things you can learn from as a writer, a storyteller. You can learn from them consciously, but even if you’re just lying on the sofa, vegging out (what kind of vegetable are you? a carrot? a cauliflower? and why?), your subconscious mind is learning learning learning, because if you’re a writer, it never stops learning.

Now, this is not to say that you should spend your entire life watching YouTube videos, or even reading The Atlantic. Or even reading Isabel Allende. At some point, you need to do what you were made for and actually write. But as you write — as you try to capture your ideas in prose or verse — everything you ever watched or listened to or read will come to help you. It will form the mental material for you to work with. A joke you heard a comic tell on a Netflix special will suggest a way a character can say something, a turn of phrase. You will describe the utter mess a character makes of a bedtime routine, and that mess (“Lydia could not fall asleep. Had she meditated the wrong way? There was a right way and a wrong way, and surely she had done it the wrong way. She should get up and watch that YouTube video again. The woman with the soothing voice, who had tortoiseshell-framed glasses and some sort of PhD although it was not entirely clear what her doctorate was actually in, would tell her. And then she would mediate the right way, and be able to fall asleep. She checked her phone. It was 3:10 am.) becomes characterization.

I would expand this to more than YouTube videos or podcasts or magazine articles. Try to be one of those people on whom nothing, not the colors of the fall leaves, not the way to darn a sweater with a hole in it, not the various ways in which people speak when they are just starting to learn English, is lost. Watch and listen and learn. Notice and notice and notice. Be infinitely curious. Have a hundred tabs open in your brain.

Recently, for the novel I’m currently working on, I had to research Pop-Tarts. Did you know that there are now chocolate chip pancake Pop-Tarts? What strange, uncanny things they are, those toaster pastries: neither quite breakfast nor dessert. When does one eat them? As far as I can tell, they are almost always eaten as snacks. There is, in fact, no proper time to eat Pop-Tarts except in between meals, surreptitiously, hiding the crumbs afterward. In my novel, there is a fairy creature with an inordinate fondness for them. They seem like the sort of thing fairy creatures would like.

One nice thing about being a writer is that nothing is ever really wasted. As long as, afterward, you write about it . . .

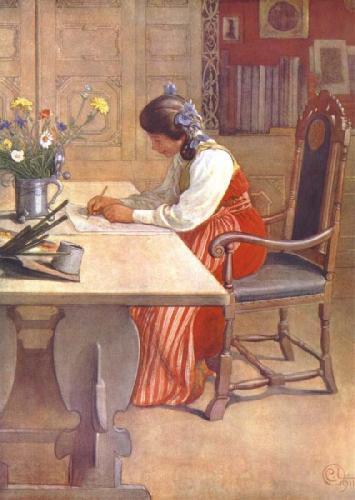

(The image is Hilda by Carl Larsson.)