100 Years of Gatsby is Quite Enough

ReaderCon 34 — an annual literary speculative-fiction convention — ran this past weekend, and I was fortunate to attend. Among the panels I took part in (The International Imagination in a Time of Nationalism, Bisexuals in Science Fiction: Still Hip After All These Years?, We Need to Talk About Gaiman, and my first kaffeeklatsch), I moderated one titled The Next Great Gatsby.

The description of the panel was as follows: At Readercon 33, Max Gladstone mentioned that The Great Gatsby flopped upon publication—and therefore was cheap to send to American soldiers abroad in WWII, which resulted its revival. He asked the audience to imagine how great a world would be in which, for some reason, copies of Sarah Caudwell's Thus Was Adonis Murdered [1981] were suddenly everywhere. What other books ought to be suddenly ubiquitous?

With an hour to fill and the panelists’ concerns that the event not become a listicle, I wrote the following essay to wrestle the discussion onto a new track. The original essay, not the two-minute version I read at the start of the panel, is printed here.

In 1943, something remarkable happened. The Council on Books in Wartime (a nonprofit organization) launched the Armed Services Editions (ASE) —122 million books (1,322 distinct titles) — and distributed them to soldiers overseas. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald was included not because it was great, but because, being fairly unsuccessful at launch, it was cheap.

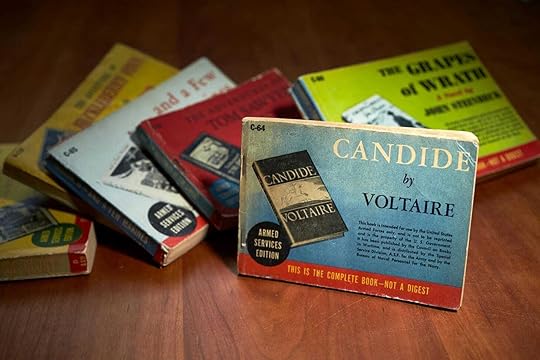

Part of the University of Nevada’s collection of ASE titles. The only complete collection is in the Library of Congress.

Part of the University of Nevada’s collection of ASE titles. The only complete collection is in the Library of Congress.The troops treasured these pocket-sized paperbacks making them 'as popular as pin-up girls.' They recommended them to each other, wrote fan letters to authors, and read everything from westerns to Shakespeare, technical manuals to romance novels. Two-hundred and fifty of these books were written by women, not a huge number but considering the times…

The ASE was deliberate social engineering. The program was created to send the following messages:

This is what we're fighting for - The heavy emphasis on American classics (Twain, Whitman, Steinbeck), frontier stories, and books about American places and people reinforced that soldiers were defending a rich, diverse cultural heritage worth preserving.

Democracy means access to all knowledge - By including everything from Shakespeare and Dickens to popular westerns and romance novels, the Council rejected cultural elitism. High literature sat alongside pulp fiction, science texts next to humor collections, suggesting that in a democracy, all reading has value and everyone deserves access to the full spectrum of human knowledge and entertainment.

We are a people of both action and reflection - The mix of adventure stories, practical guides, and contemplative literature suggested Americans were not just warriors but thinkers, dreamers, and builders who could handle both Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls and technical manuals about electronics.

Escapism and engagement are both necessary - By providing both pure entertainment (detective stories, fantasies) and serious contemporary analysis (war correspondents' accounts, political treatises), the Council acknowledged that fighting men and women needed both mental relief and intellectual tools to understand their historical moment.

American culture is inclusive and cosmopolitan - The presence of translated works, books about other cultures, and authors from diverse backgrounds (including women and minorities) projected an image of America as open to the world's best ideas while confident in its own values.

The overarching message was profoundly democratic: We are fighting for a civilization where every person has the right to think, dream, laugh, and learn freely.

The warriors came home from the conflict addicted to coffee, cigarettes, and reading.

Now fast-forward to today. Only 29% of men read fiction, compared to a higher-but-not-much-higher 49% of women. Recent press have described men browsing bookstores alone, struggling to find books that speak to them, abandoning novels for digital entertainment. Books are no longer social connectors.

Meanwhile, Gatsby — the accidental survivor now a century old — has spent seventy years dominating high-school curricula, teaching fatalism with its 'borne back ceaselessly into the past,' promoting cynicism over constructive engagement, reducing complex social issues to simple symbols and moralistic judgments. (Gatsby’s secondary-school takeover was also largely an accident, due its brevity and easy fit within the New Criticism popular in the day. )

But those WWII soldiers proved something crucial: when books serve as tools for emotional processing and social connection — not just entertainment — people embrace them eagerly. The program worked because it had clear democratic values and treated reading as essential for navigating difficult times.

So today we're asking: if we could deliberately canonize books the way we accidentally did with Gatsby, what should those books be? What messages do we want to send? What books could counter fatalism with hope, gatekeeping with inclusion, cynicism with constructive engagement?

What books ought to be suddenly ubiquitous?

Among the questions I created for the panel were:

What book would create the most positive chaos if it suddenly appeared in every American household? (My answer was Chuck Tingle’s Camp Damascus.)

If you could magically replace Gatsby as the universal high school text, what would you choose and what cultural messages would it send?

What book changed your perspective on genre’s potential for serious cultural work?

If you were designing a new book-distribution program for today’s challenges — climate change, polarization, technological disruption, nationalism — what would be your first five titles?

Beyond individual titles, what would need to change about how we discover, discuss, and distribute books to replicate the ASE program’s democratic impact?

Any thoughts?

Thanks for reading twenty-first-century blues! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.