19th-Century Mug Shots: The Face(s) of Counterfeiting

As we mentioned earlier this summer, counterfeiting was a huge problem in the years after the Civil War, when the nation struggled to establish a single paper currency. This led to the creation of the U.S. Secret Service to track down counterfeiters and, in turn, to the agency compiling what we now call mug shots.

The Library acquired more than 1,200 of these from the collection of ace counterfeiting detective Bill Kennoch, and they are a marvelous glimpse at how we lived and looked in days gone by. (These fall into the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse category, as they are copyright free and yours to use in any way you wish.)

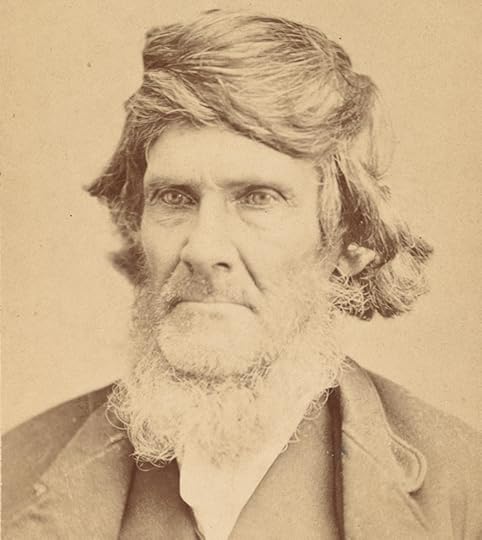

Orvill Ball took this wig (or wild combover?) to extremes in this photograph after his arrest for counterfeiting in Scranton, Pennsylvania, between 1865 and 1886. Photo: Sedgwick S. Hull. Prints and Photographs Division.

Orvill Ball took this wig (or wild combover?) to extremes in this photograph after his arrest for counterfeiting in Scranton, Pennsylvania, between 1865 and 1886. Photo: Sedgwick S. Hull. Prints and Photographs Division.Since counterfeiting was more fraud than violent crime, almost anyone could play a role in it, from making false bills or coins, distributing them in bulk or just passing them off as legit currency in a dry goods store.

This meant, as evidenced by the photographs, that it was open to young and old, rich and poor, men and women, and any and all races and ethnic groups. Most of these were small-time practitioners of the trade, not the type of outlaw that mobilized manhunts and generated headlines.

The aging Orvill Ball did not achieve any worldly renown before or after being picked up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The back of the card, where agents often scribbled the charges against the accused, only has his name and that of the photographer. Still, for this moment in time, he did cut quite the figure with that head of hair, whether it was all his or not.

Mark Michaelson, the collector and author of “Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots,” a 2006 photo book, described these sorts of small timers to the New York Times this way:

“I started to figure out I wasn’t interested in famous criminals or people who’d committed big crimes or very violent crimes. I wanted the small-time people, petty crooks who just fell through the cracks. Instead of being the most wanted, these were the least wanted.”

The Kennoch collection photographs of these least (or somewhat) wanted cover a range about 30 years, from roughly 1860 to 1890, an era when modern criminology was in its infancy. Police around the world had dabbled in using photographs in crime investigations since the 1840s, but it was a French police official, Alphonse Bertillon, who formalized the mug shot in Paris in the early 1880s.

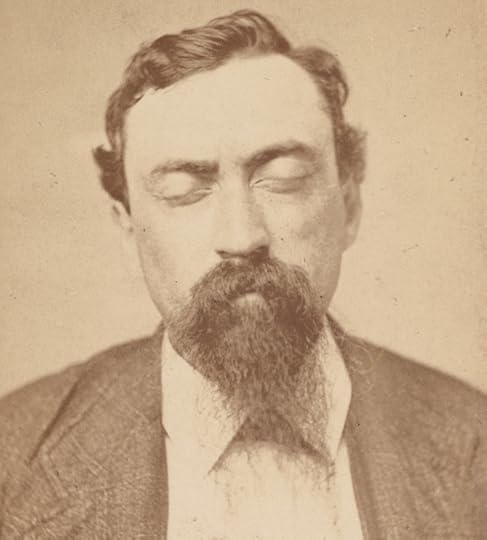

John Duffy was arrested in Philadelphia for counterfeiting in the late 19th century. Like many a portrait subject, he blinked when the shutter snapped. Photo: Charles H. Spieler. Prints and Photographs Division.

John Duffy was arrested in Philadelphia for counterfeiting in the late 19th century. Like many a portrait subject, he blinked when the shutter snapped. Photo: Charles H. Spieler. Prints and Photographs Division.Bertillon used one shot of the suspect facing the camera, the second in profile, and attached these images to a sheet of information about the suspect, most notably several physical measurements that were meant to augment identification. The fingerprint eclipsed most of the other physical measurements a few decades later, leading to the standards still in use today.

The U.S. Secret Service, though, had no standard police cameras. Instead, agents hustled the accused over to the nearest portrait photography studio, where they sat for photos that were usually for cartes de visite, or society calling cards. Such a photograph would have otherwise been a special occasion, if not for the fact that many of the sitters were headed to prison.

So, who among us cannot sympathize with the accused John Duffy? He was arrested in Philadelphia, walked over to have his picture taken … only to blissfully close his eyes, as if he’d just dozed off, when the camera snapped his picture. The man seems peaceful and serene, even while getting booked.

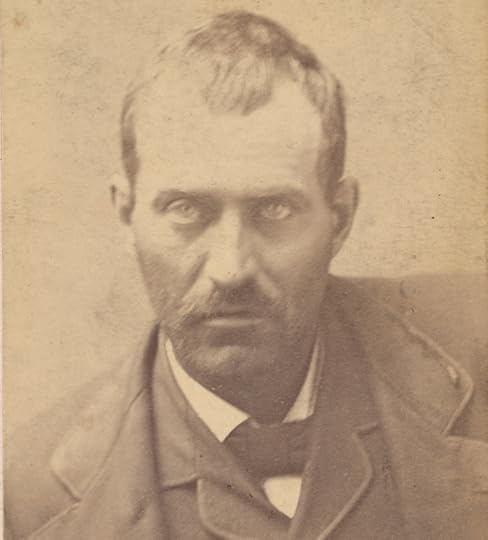

Nickolas E. Cooper of Bay City, Michigan, was booked for counterfeiting coins. Police said he was violent and dangerous. Photo: Miller Bros. Prints and Photographs Division.

Nickolas E. Cooper of Bay City, Michigan, was booked for counterfeiting coins. Police said he was violent and dangerous. Photo: Miller Bros. Prints and Photographs Division.Not everyone seemed harmless. Nickolas E. Cooper was picked up in Michigan for counterfeiting coins. Police started tracking him in Bay City, but only caught up with him in Detroit. Things got ugly. From the brief narrative on the back of the photo: “Went violently insane put into Lunatic Asylum at Pontiac, Michigan. Doctor states that the man is not crazy, only playing it.”

Those eyes, though. They have a glint. It’s the kind of thing you remember, even a century and a half later.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 73 followers