The Book and the Wardrobe

In the last few days I’ve been reading Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which is about as far from The Chronicles of Narnia as one can get, although Holly Golightly would make a very good White Witch, tempting Edmund with Turkish Delight and probably vermouth. But reading Truman Capote’s novella made me think about how every book — at least every good book, and perhaps even a not particularly good one — is a wardrobe, which makes it both enchanting and dangerous.

You probably remember what happened to Lucy, Edmund, Susan, and Peter when they went through the wardrobe? First, they entered an enchanted (and enchanting) country, where the animals could talk. The most important of those animals was Aslan, the great lion. The four children had adventures and participated in battles, but in the end it was Aslan who defeated the White Witch — only Aslan could do so. He saved Narnia, and Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy ruled as kings and queens in Cair Paravel by the sea. Meanwhile, Aslan came and went as he wished. The four children grew up in Narnia, then were pulled back into their own country and became English school children again. Although they spent years in Narnia, in our world it seemed as though only minutes had passed. In a later book, we are told that time works differently in Narnia and our world — it could work the other way around as well, with minutes passing in Narnia and aeons in England.

We know that the tale of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a religious fable of sorts, with Aslan as a Narnian Jesus, but can you see how it’s also (and perhaps even more fundamentally) an allegory for the act of reading itself? Entering the wardrobe is like entering a book. You have all sorts of adventures there, and everything within the book is alive — it speaks to you, even if it might not speak in our world. It is all text, and therefore it’s all talking in your head. Here is how Breakfast at Tiffany’s starts:

“I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red velvet that one associates with hot days on a train. The walls were stucco, and a color rather like tobacco spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its gloom, it still was a place of my own, the first, and my books were there, and jars of pencils to sharpen, everything I needed, so I felt, to become the writer I wanted to be.”

The items listed by the narrator don’t themselves speak within the story, but they are spoken. As you read, you hear a voice in your head, describing the sofa and chairs upholstered in itchy red velvet. You hear, or at least I do, the k-sounds in stucco and tobacco, and there is something particularly visceral at the end of that sentence with the s-p-i-t of spit. Your mind almost spits it out. For me, at least, it’s as though everything in the paragraph is speaking — not just the narrator, but the walls of the apartment themselves. Everything becomes meaningful. I have entered an enchanted country. (By the way, I am drawing here on the theories of David Abrams on how text functions — how it becomes animate in our heads as we read. You can find out more in his book The Spell of the Sensuous, especially the chapter “Animism and the Alphabet.”)

While I am in that country, I forget time is passing in my world, although the clock keeps ticking. In reading, I myself become timeless — subjectively, I step out of chronological time for a while. And yet time passes within the story as well. The narrator describes his own past, when he knew Holly — at the time he is writing, she is somewhere else in the world, perhaps in Africa but who knows. The narrative itself takes place over a number of months. So there I am, sitting in bed, propped against my pillows, reading a book, and time is going all wonky — it’s passing in my world, but I don’t feel as though it’s passing, and it’s also passing in the story, but differently than in my world, and temporarily at least, I am living those months with Holly Golightly. I am in Narnia, on the East Side of New York, during the lean years of the Second World War. (Funnily, I never thought about the fact that the Narnia books and Breakfast at Tiffany’s are connected in that way — they both take place during wartime. Holly is about the same age Susan grows up to in Narnia. C.S. Lewis would not have let Holly back into Narnia either.)

In the enchanted Narnia of the book, I have a guide who leads me through the narrative, telling me where to go and what to think. That guide may be reliable or unreliable — in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, my guide is initially Mr. Beaver, but then it becomes Aslan himself. In Breakfast at Tiffany’s, it’s the unnamed narrator. But Aslan is more than a guide. He is the son of the Emperor-over-the-Sea, who is God, but also the Author. Can you see how and why? Aslan is more than a character within the book — he also writes its plot. In a sense, he is an extra-narrative force that steps outside the parameters of the story to actually create it. He invokes the laws of Deep Magic established before the dawn of time, before narrative began. And with them, he changes the story. If we return to the religious fable, he is God in the way that Jesus is also God, and remember that God is an author. He creates the world through the Word. Lewis’s pal J.R.R. Tolkien made this point in “On Fairy-stories” when he said that God is a creator and the writer is a sub-creator; writing is a sub-creation that mirrors the original creation.

When Lucy and her siblings step through the wardrobe, they enter a magical country created by an Author. They enter a story in which they participate, during which all sorts of things happen to them, including winning a battle, becoming kings and queens, and even growing up. Then, they are whisked back to through the wardrobe into their own ordinary realities. They are the same yet different. The Author brings them back to that country again — in the next book. Going to Narnia is analogous to reading.

When you were a child, did you try to find the wardrobe? Did you test the back of every wardrobe you saw, just to see if it might lead you to Narnia? I certainly did. My argument here has been that every book is a wardrobe. It functions just like the one in The Chronicles of Narnia (and like that wardrobe, sometimes it works, sometimes not). The best books, and some not very good ones, are deeply immersive experiences. They are enchanted and potentially dangerous, because they might change you permanently — that is why people keep trying to ban them. Do you remember the most magical place in the entire Narnia series? It was the Wood Between the Worlds in The Magician’s Nephew. From there, you didn’t need a wardrobe — you could travel into any world at all. After a childhood of testing wardrobes, it is reassuring to me, personally, to think that I have an entire Wood Between the Worlds right on my bookshelves.

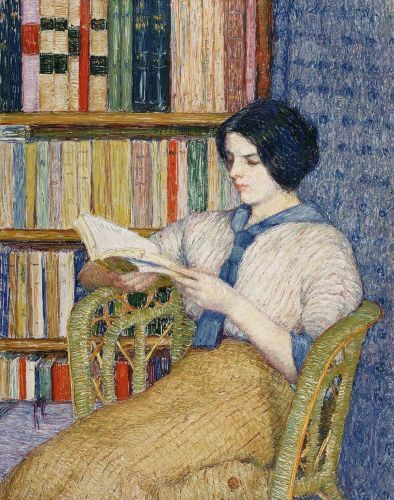

(The image is Woman Reading by Torajiro Kojima.)