How Do We Know You’re Not a Communist? The Red Scare that Ripped America Apart

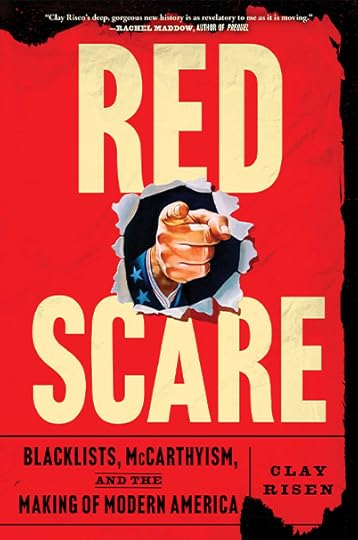

Clay Risen spent six years working on “Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism and the Making of Modern America,” a narrative history of the anti-communist panic that consumed the country in the decade after World War II. Americans, fearing the communist Soviet Union and communism advancing across Asia, grew paranoid. While the threat of Soviet espionage was very real – Soviet spies had infiltrated the Manhattan Project, to build the atomic bomb, for example – but what Joseph McCarthy, a U.S. senator from Wisconsin, did in the 1950s was turn mostly old issues into an ongoing hysteria. Thousands of innocent people lost their jobs, books were banned and charges of communist leanings were taken to extremes. Risen will discuss the book at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6.

This conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Timeless: Part of the impetus for this book actually came from your childhood, when your grandfather, who had worked for the FBI during the Red Scare years, told stories about that work.

Clay Risen: Sure, when I was a kid he’d tell this one story in particular, about a time he was working in Chicago. He got a call from a guy who said, “Hey, you should check out Mr. Gruber, he’s a Nazi.” So he’d go check out Mr. Gruber. And Gruber would say, “A Nazi? That’s ridiculous. I came here as a kid and my son is in the Army, and I have a flag in my store. What you should do is check out Mr. Rosenstein, he’s a communist.” So, my granddad would go see Rosenstein, who would say, “That’s ridiculous. I’m a registered Republican.” Then he interviewed the neighbors, who’d say, “Oh, Gruber and Rosenstein, those guys hate each other. They’ve been at it for years. They’re just trying to get the other one.” It’s a funny story, but what stuck with me was, even before I could articulate it in these terms, was that these guys were using the police power of the state — my grandfather — to go after each other. It was funny at first, but it’s also really scary when you think about it.

Timeless: Everyone remembers Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin senator who rose to fame, or infamy, as the most visible red baiter of the era. Who do we not remember who also played a critical role?

The person who really kicked everything off was J. Parnell Thomas, a U.S. representative from New Jersey. In 1947, he was the chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee and began to go after any and all suspicions of communist connections. His biggest target was Hollywood. This is where the famous Hollywood 10 witnesses came and testified, they were all resistant to the committee and they all went to jail. Even then, it was clear that Thomas was grasping at straws, that he was self-promoting, and so he had picked the biggest target: Hollywood.

Also, when you’re looking at the life story of Richard Nixon, you look at the way that he carried himself and the way that he used HUAC to improve his standing? It was pretty masterful. And I don’t think he was completely wrong. He was the driving force in going after Alger Hiss, and he was right about him. [Hiss was a high-ranking State Department official who was charged in 1950 with spying for the Soviet Union during the 1930s. He was convicted of perjury and went to prison but maintained his innocence.] So Nixon is another figure who really helped elevate the Red Scare. Without him, I don’t think the Red Scare, or the campaign of adamant anti-communism in Congress, would’ve had the widespread purchase and legitimacy that it did had Nixon not been there to give it a little polish.

Author Clay Risen. Photo: Kate Milford.

Author Clay Risen. Photo: Kate Milford.A lot of the communist accusations in the Red Scare of the 1950s really had to do with political groups and actions during the New Deal era of the 1930s, not so much post-World War II espionage, when the Soviet Union was our clear Cold War enemy.

By the 1950s, New Deal progressivism had really lost a lot of its steam. That’s when the backlash set in. In the Red Scare, it was almost like they were pursuing ghosts. The big cases at the time — things like the Alger Hiss case — revolved around things that he was said to have done in the 1930s. No one accused him of being a current spy. Alistair Cooke, the British journalist, wrote a book about the era, “A Generation on Trial: USA v. Alger Hiss,” That that really captured what was going on. So, much of the Red Scare was this kind of delayed reaction from a fight that had had relevance in the 1930s, but almost seemed beside the point in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A lot of the headlines were about targets in Hollywood, at first screenwriters and then big names on screen.

Yes. And just to underline, these accusations were baseless or based on some set of criteria that really had no place in a democratic society. Things like, “You signed a petition that was circulated by an alleged communist front in 1935.” Or, “You appeared onstage with Paul Robeson, and we all know Paul Robeson [the actor, singer and activist] is a left-wing radical.”

So, there were these self-appointed investigators and lawyers who would go after people who had been smeared or targeted in some way and say, “Come to us with your issue, Hollywood stars, and tell us why you were wrong. Write it all out and if we believe you, we will lobby your case to the executives of Hollywood. But if we don’t believe you, we’re going to tell the executives of Hollywood that you are to be banned forever.”

And they were powerful enough to get scores of letters from names like John Houseman, John Ford and Vincent Price. Lena Horne had a file that was particularly extensive and really kind of mind blowing, but these groups went back and forth between themselves, like, “Is Lena Horne sufficiently sorry for what she did?” It was very much a star chamber.

Was there ever a point at which people said, “OK all that’s over and, wow, that was a terrible thing?”

No, there was never a reckoning. There was never really a moment where the country said, “We need to atone for this.” Or even that everyone recognized that something bad happened. Part of the Red Scare that is different maybe from things like Jim Crow or other periods of injustice in American history is that even to this day, there are a lot of people who think, “Yeah, that was OK,” or “We got a little carried away, but it was justified.” Or they say, “Well, what we did was fine. What McCarthy did was bad.” There’s a lot of that. Harry Truman was, I think maybe an exception. He created an executive order in 1947 that was the first real program for loyalty tests in the federal government. It very quickly got out of hand. Later, he wrote in his memoirs that he essentially said, “I made a huge mistake.”

What was your ultimate takeaway? Is it just a sad chapter in American history or something more ominous?

I think it’s something much more ominous. I think that, look, this is a country founded on the belief that we all have inalienable liberties and that we are all sovereign individuals who delegate certain powers to the government. And so fundamentally, we should hold that as the highest priority. And yet the Red Scare is one example among many, unfortunately, where we very willingly threw that all aside. And it’s not that there wasn’t any justification. The Cold War was real and Soviet espionage was real, but they were used as an excuse to trample on the civil liberties of tens of thousands of Americans. I mean, broadly speaking, millions of people lives were intruded upon by investigators. I don’t think that we really learned our lesson from that.

I think that what the Red Scare indicates is that these things are a recurrent aspect of American political life. The fundamental mechanisms come back time and again, and in a country that depends so much on freedom of speech and the freedom of association — and just the freedom to live your life the way you want — we give that all up so easily. We need to remember that.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 73 followers