Must We Kill Our Darlings?

Sandra Neily here. (Revising and sharing a previous post I needed to hear this month.)

Stephen King drove the knife deep: “Kill your darlings, kill your darlings,” he wrote. “Even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart, kill your darlings.”

I think King got the ego thing right. Cutting words we love is often painful and personal as we let the novel drive our editing. If words we love do not efficiently and tightly drive the story forward, the “darlings” have to go … but not die if we save them. into my next mystery.

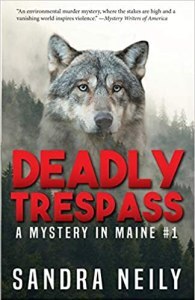

Over 10 years ago I cut a scene from “Deadly Trespass.” I am glad I saved it as I am just about to bring the narrator’s mother into my next mystery.

I’ve reworked it a bit but kept this passage.

********

My mother had an ancient neighbor who yelled “never!” at odd moments. When we had time, Pock and I visited around the nursing home. My dog drooled and wagged like their lost pets, and often, just as friendship kicked in, we’d find an empty bed and a repainted room while Pock whined softly.

Was a nursing home in my future? The “never” screamed at me from across the hall was a good omen. My mother lay flat, looking at the ceiling. Except for her bony shoulders and the small ridgeline of her legs, she showed less mass than her rumpled bedding. She looked like a desert horizon line—brown and pink weathered rock barely visible above white sand.

Her face lifted into a wide smile. She patted the bed for Pock to jump up. “Where’s Annie. It’s time for her walk.”

My “Jackie” with my mother … long ago.

Annie was long gone so I agreed and used the past tense at the same time. “Right, Mum. Annie was Beagle-feisty. A real ankle biter.”

I reached for the bed controls, raised her head, and stretched Pock down her side, placing his head under her fingers. Her cheeks—flawless and translucent—glowed. Only the clawed hands on my dog and her spider web strands of hair were genuine age markers. As a child I’d been careless with her china, so she’d packed it away from my dirty fingers. At ninety-two my mother was more delicate than her disappeared china. She reached for my hands and clutched them to her chin.

I lifted her nail file. “Shall we work on your hands?” I asked

I reached for a chair and dropped into it, hands supporting my pounding head. I needed water. My cells felt squeezed dry. “You asked me to come. Why?”

She shot me a sturdy stare. “You know, dear, nothing is ever lost. Your father’s not. Annie’s not. If I don’t see you for days, I know you are not lost. All of God’s creation is in its rightful place.

I moaned and collapsed over my knees.

She picked muffin crumbs from her sheets and placed them on Pock’s quivering lips. “Misplaced. Sometimes we misplace things, but God’s plan restores order. Annie is not lost. Your father is not lost. You are not lost.”

I rose and leaned over her bed, wrapping both dog and mother in my arms. “But Mum, why did you really call me?”

Her moist, blue eyes squinted at the wall where we’d hung a large poster of family photos. I wore a starched Easter dress and lifted a basket of eggs. My brother rowed a boatload of beagles. My parents toasted each other, heads thrown back with laughter. “I was lonely,” she whispered.

I used to tell a therapist that I’d been dropped and raised by wolves, but that didn’t really describe my childhood. Real wolf pups probably had it better. They grew up under the pack’s watchful eyes until they could hunt for themselves. There was always warm fur, fresh food, and careful surveillance.

I’d raised myself in sea cave hideouts carved by the tide or mossy thickets where I stashed canned peaches and library books. The seagulls and squirrels knew more about me than my parents did. After school I leashed a beagle and escaped up the street, never wondering why no one asked me where I was going.

I inched onto her bed and arranged my head next to her shoulder, careful not to press weight on her. Her strong pulse beat through skin so thin sheets could cut her arms. My brother and I used to put frog eggs in a fishbowl on the table and watch beating hearts develop from transparent cells. Strong life through thin tissue. My mother was not dying— just lonely.

I knew all about lonely; I’d learned it at an early age.

*******

I have a file of discarded “Darlings.” There aren’t many in it, but the ones that are, are darlings.

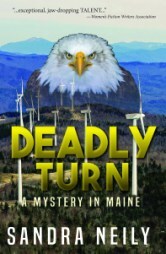

S andy’s second Mystery in Maine Deadly Turn was published in 2021. Her debut novel, “Deadly Trespass, A Mystery in Maine,” won a national Mystery Writers of America award, was a finalist in the Women’s Fiction Writers Association “Rising Star” contest, and was a finalist for a Maine Literary Award. In 2026 “Deadly Harvest” will return Patton, her badly-behaved dog, and game warden Moz as they meet up with even more threatened wildlife. Find her novels at all Shermans Books and on Amazon. Find more info on Sandy’s website.

andy’s second Mystery in Maine Deadly Turn was published in 2021. Her debut novel, “Deadly Trespass, A Mystery in Maine,” won a national Mystery Writers of America award, was a finalist in the Women’s Fiction Writers Association “Rising Star” contest, and was a finalist for a Maine Literary Award. In 2026 “Deadly Harvest” will return Patton, her badly-behaved dog, and game warden Moz as they meet up with even more threatened wildlife. Find her novels at all Shermans Books and on Amazon. Find more info on Sandy’s website.

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 506 followers