The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

On Politics

PHILOSOPHY AND POLITICS

>

WE ARE OPEN - WEEK 8 AND WEEK 9: - (September 21st 2015 - October 4, 2015) - Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero - page 111 - 148 - (No Spoilers, please)

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 2:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 06, 2015 06:00PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Folks, we are kicking off the long term discussion on politics and philosophy. The book we will be using is a very comprehensive work by Alan Ryan titled On Politics: A History of Political Thought from Herodotus to the Present.- we welcome you to this discussion which will last for a year. There is no rush, we are taking our time and enjoying a lot of history, discussion, videos along the way. We are happy to have all of you with us. I look forward to reading your posts in the months ahead.

message 3:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 05:29AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Everyone, for the week of September 21st, 2015 - October 4th, 2015

, we are reading Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero.

The eighth and ninth week's segments reading assignment are:

WEEK EIGHT AND WEEK NINE: September 21st, 2015 - October 4th, 2015

Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero - pages 111 - 148

Chapter Overview and Summary

Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero

These weeks we will be discussing the following:

a) Politics for Statesmen, not philosophers

b) The peculiarities of Rome are explained

c) Roman success and its basic tenets

d) What freedom is and what it is not

e) Three Orders of Citizens

f) Cicero's and Polybius's political theories

g) Good laws and good citizens

h) Theories of the mixed republic

i) Motors of political change

j) Self-discipline

, we are reading Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero.

The eighth and ninth week's segments reading assignment are:

WEEK EIGHT AND WEEK NINE: September 21st, 2015 - October 4th, 2015

Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero - pages 111 - 148

Chapter Overview and Summary

Chapter 4: Roman Insights: Polybius and Cicero

These weeks we will be discussing the following:

a) Politics for Statesmen, not philosophers

b) The peculiarities of Rome are explained

c) Roman success and its basic tenets

d) What freedom is and what it is not

e) Three Orders of Citizens

f) Cicero's and Polybius's political theories

g) Good laws and good citizens

h) Theories of the mixed republic

i) Motors of political change

j) Self-discipline

message 4:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 06, 2015 06:20PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

message 5:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 19, 2015 06:42PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The chapter begins:

"Neither of the subjects of this chapter was primarily a philosopher; Cicero was a statesman, although he was a more accomplished philosopher and a less accomplished statesman than he supposed. Polybius was a soldier, a diplomat, and the third of the great Greek historians after Herodotus and Thucydides. His intellectual successors as writers of political and military history are the Roman historians Tacitus and Livy. Polybius's work entitled The Rise of the Roman Empire has survived only in part; but his explanation of the extraordinary political and military success of the Romans provided Cicero and writers thereafter with their understanding of the Roman or "mixed republican constitution", and the dangers to which such a mixed republic might succumb. Since the constitutions of modern republics owe more to Republican inspiration than to Athenian democracy, we are ourselves his heirs.

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo)

"Neither of the subjects of this chapter was primarily a philosopher; Cicero was a statesman, although he was a more accomplished philosopher and a less accomplished statesman than he supposed. Polybius was a soldier, a diplomat, and the third of the great Greek historians after Herodotus and Thucydides. His intellectual successors as writers of political and military history are the Roman historians Tacitus and Livy. Polybius's work entitled The Rise of the Roman Empire has survived only in part; but his explanation of the extraordinary political and military success of the Romans provided Cicero and writers thereafter with their understanding of the Roman or "mixed republican constitution", and the dangers to which such a mixed republic might succumb. Since the constitutions of modern republics owe more to Republican inspiration than to Athenian democracy, we are ourselves his heirs.

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo)

message 6:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 20, 2015 01:04PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

More:

"Polybius was a highly educated Greek aristocrat from Achaea, in the northwestern Peloponnese, and as a young man was active in the military and political life of his homeland. He was born at the beginning of the second century, sometime after 200 BCE and before 190. Roman military power had by then reduced the kingdom of Macedon to client status, in spite of attempts by kings of Macedon to recover their independence. At the end of the last of these Macedonian Wars in 168, he was one of many upper-class Achaeans taken off to Italy for interrogation and to be kept as a hostage.

He was in exile for eighteen years, during which time he had the good fortune to become close friends with Scipio Africanus the Younger, whom he served as tutor and lifelong friend he remained. Scipio was the son of the Roman general who had won the decisive Battle of Pydna against the Macedonians, where the younger Scipio had also fought. Grandson by adoption of Scipio Africanus the conqueror of Hannibal, he was responsible for the final destruction of Carthage in 146.

That is the terminus ad quem of Polybius's Rise of the Roman Empire. Scipio the Younger plays the central - fictional - role in Cicero's De republica, articulating the values of Roman republicanism in its final years of glory before the republic's institutions decayed and civil war overtook them. Polybius spent his exile in Rome, where he served his friend as secretary and learned all there was to know about the workings of the Roman republic.

In 150 he was allowed home, although he remained close to Scipio, accompanied him during the Third Punic War, and witnessed the destruction of Carthage. Polybius later served his homeland well by acting as a mediator with the Romans after another ill-judged rebellion ended as badly as rebellions against Rome usually did; he did such an excellent job that after his death a remarkable number of statues was erected in his honor all over Greece. The fate of Carthage, sacked, put to the flames, and razed to the ground, suggests the value of his services.

His last years are obscure, but he is said to have died after a fall from his horse at the age of eighty-two in 118. The tale attests to a temperament more friendly to soldiers and statesman than to speculative philosophers".

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo)

by

by

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero

"Polybius was a highly educated Greek aristocrat from Achaea, in the northwestern Peloponnese, and as a young man was active in the military and political life of his homeland. He was born at the beginning of the second century, sometime after 200 BCE and before 190. Roman military power had by then reduced the kingdom of Macedon to client status, in spite of attempts by kings of Macedon to recover their independence. At the end of the last of these Macedonian Wars in 168, he was one of many upper-class Achaeans taken off to Italy for interrogation and to be kept as a hostage.

He was in exile for eighteen years, during which time he had the good fortune to become close friends with Scipio Africanus the Younger, whom he served as tutor and lifelong friend he remained. Scipio was the son of the Roman general who had won the decisive Battle of Pydna against the Macedonians, where the younger Scipio had also fought. Grandson by adoption of Scipio Africanus the conqueror of Hannibal, he was responsible for the final destruction of Carthage in 146.

That is the terminus ad quem of Polybius's Rise of the Roman Empire. Scipio the Younger plays the central - fictional - role in Cicero's De republica, articulating the values of Roman republicanism in its final years of glory before the republic's institutions decayed and civil war overtook them. Polybius spent his exile in Rome, where he served his friend as secretary and learned all there was to know about the workings of the Roman republic.

In 150 he was allowed home, although he remained close to Scipio, accompanied him during the Third Punic War, and witnessed the destruction of Carthage. Polybius later served his homeland well by acting as a mediator with the Romans after another ill-judged rebellion ended as badly as rebellions against Rome usually did; he did such an excellent job that after his death a remarkable number of statues was erected in his honor all over Greece. The fate of Carthage, sacked, put to the flames, and razed to the ground, suggests the value of his services.

His last years are obscure, but he is said to have died after a fall from his horse at the age of eighty-two in 118. The tale attests to a temperament more friendly to soldiers and statesman than to speculative philosophers".

by Polybius (no photo)

by Polybius (no photo) by

by

Marcus Tullius Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero

message 7:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 10:49AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

The Punic Wars - Spend some time understanding these wars

http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

Source: History.com

A good easy youtube about the history of the Punic Wars - even for kids

https://youtu.be/gYck2OxqK9M

Rome: The Punic Wars - I: The First Punic War - Extra History

https://youtu.be/EbBHk_zLTmY

First Punic War - (264 - 241BC)

- Mainly naval war - some land fighting in Sicily and Africa

- Started as local conflict between Hiero of Syracuse and Mamertines of Messina

- The Mamertines asked for Carthage's help then doublecrossed them and asked for help from the Romans

Some of the more important or larger battles:

- Battle of Agrigentum - 262 BC

- Battle of the Lipari Islands - 260 BC

- Battle of Tunis

Mercenary Wars - (240 - 238 BC) - Rome seizes Sardinia and Corsica

Location: North Africa, Carthage, Utica, Tunisia, Sicca Veneria (modern El Kef)

The Mercenary War (240 BC – 238 BC), also called the Libyan War and the Truceless War by Polybius, was an uprising of mercenary armies formerly employed by Carthage, backed by Libyan settlements revolting against Carthaginian control.

The war began as a dispute over the payment of money owed the mercenaries between the mercenary armies who fought the First Punic War on Carthage's behalf, and a destitute Carthage, which had lost most of its wealth due to the indemnities imposed by Rome as part of the peace treaty. The dispute grew until the mercenaries seized Tunis by force of arms, and directly threatened Carthage, which then capitulated to the mercenaries' demands. The conflict would have ended there, had not two of the mercenary commanders, Spendius and Mathos, persuaded the Libyan conscripts in the army to accept their leadership, and then convinced them that Carthage would exact vengeance for their part in the revolt once the foreign mercenaries were paid and sent home. They also persuaded the combined mercenary armies to revolt against Carthage, and various Libyan towns and cities to back the revolt. What had been a hotly contested "labour dispute" exploded into a full-scale revolt.

Heavily outmatched in terms of troops, money, and supplies, an unprepared Carthage fared poorly in the initial engagements of the war, especially under the generalship of Hanno the Great. Hamilcar Barca, general from the campaigns in Sicily, was given supreme command, and eventually defeated the rebels in 237 BC.

The war had repercussions for Carthage, both internally, and internationally. Internally, the victory of Hamilcar Barca greatly enhanced the prestige and power of the Barcid family, whose most famous member, Hannibal, would lead Carthage in the Second Punic War. Internationally, Rome used the "invitation" of the mercenaries that had captured Sardinia to occupy the island. The seizure of Sardinia and the outrageous extra indemnity fuelled resentment in Carthage. The loss of Sardinia, along with the earlier loss of Sicily meant that Carthage's traditional source of wealth, its trade, was now severely compromised, forcing them to look for a new source of wealth. This led Hamilcar, together with his son-in-law Hasdrubal and his son Hannibal to establish a power base in Hispania, outside Rome's sphere of influence, which later became the source of wealth and manpower for Hannibal's initial campaigns in the Second Punic War.

Result: Decisive Carthaginian victory

Territorial changes: Roman annexation of Sardinia and Corsica

Rome: The Punic Wars - II: The Second Punic War Begins - Extra History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lf0-Y...

Second Punic War - Referred to as The Hannibalic War or The War against Hannibal - (218 - 201 BC)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_...

- Antagonists - Carthage and Rome

- Called the Punic Wars because Rome's name for Carthaginians was Poeni, derived from Poenici (earlier form of Punici, a reference to the founding of Carthage by Phoenician settlers

- Hannibal lay siege of Saguntum - Iberian city - loyal to Rome - conflict instigation

- Most costly traditional battles of human history

- Initiated by Rome - marked by Hannibal's overland journey and crossing the Alps into Italy, also in Iberia at Carthago Nova and in Africa

- Some of the major battles: Trebia, Trasimene, Cannae, Carthage Nova, Ilipa, Zama, Metaurus as well as the Battle of the Rhone Crossing, Ebro River, Cissa

- Known strategically for Hannibal's crossing of the Alps with elephants and for Fabian strategy

Rome: The Punic Wars - III: The Second Punic War Rages On - Extra History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wT_re...

Rome: The Punic Wars - IV: The Conclusion of the Second Punic War - Extra History

Hannibal put an end to the Second Punic War. Scipio's stringent terms of surrender were to:

a) hand over all warships and elephants

b) not make war without permission of Rome

c) pay Rome 10,000 talents over the next 50 years.

The terms included an additional, difficult proviso:

d) should armed Carthaginians cross a border the Romans drew in the dirt, it automatically meant war with Rome.

This meant that the Carthaginians could be put in a position where they might not be able to defend their own interests.

https://youtu.be/McT1H-NVCMQ

The Phoenician Carthage - The Roman Holocaust - The Third Punic War - ended with the destruction of Carthage and it people.

The Third Punic War (Latin: Tertium Bellum Punicum) (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage and the Roman Republic.

This war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and focused on Tunisia, mainly on the Siege of Carthage, which resulted in the complete destruction of the city, the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome, and the death or enslavement of the entire Carthaginian population. The Third Punic War ended Carthage's independent existence.

Video - https://youtu.be/fn4EtY8pVnI

Downfall of the Carthaginian Empire

Lost to Rome in the First Punic War (264BC – 241BC) - Teal

Won after the First Punic War, lost in the Second Punic War - Green

Lost in the Second Punic War (218BC – 201BC) - Lighter Blue

Conquered by Rome in the Third Punic War (149BC – 146BC) - Purple

by

by

Adrian Goldsworthy

Adrian Goldsworthy

http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

Source: History.com

A good easy youtube about the history of the Punic Wars - even for kids

https://youtu.be/gYck2OxqK9M

Rome: The Punic Wars - I: The First Punic War - Extra History

https://youtu.be/EbBHk_zLTmY

First Punic War - (264 - 241BC)

- Mainly naval war - some land fighting in Sicily and Africa

- Started as local conflict between Hiero of Syracuse and Mamertines of Messina

- The Mamertines asked for Carthage's help then doublecrossed them and asked for help from the Romans

Some of the more important or larger battles:

- Battle of Agrigentum - 262 BC

- Battle of the Lipari Islands - 260 BC

- Battle of Tunis

Mercenary Wars - (240 - 238 BC) - Rome seizes Sardinia and Corsica

Location: North Africa, Carthage, Utica, Tunisia, Sicca Veneria (modern El Kef)

The Mercenary War (240 BC – 238 BC), also called the Libyan War and the Truceless War by Polybius, was an uprising of mercenary armies formerly employed by Carthage, backed by Libyan settlements revolting against Carthaginian control.

The war began as a dispute over the payment of money owed the mercenaries between the mercenary armies who fought the First Punic War on Carthage's behalf, and a destitute Carthage, which had lost most of its wealth due to the indemnities imposed by Rome as part of the peace treaty. The dispute grew until the mercenaries seized Tunis by force of arms, and directly threatened Carthage, which then capitulated to the mercenaries' demands. The conflict would have ended there, had not two of the mercenary commanders, Spendius and Mathos, persuaded the Libyan conscripts in the army to accept their leadership, and then convinced them that Carthage would exact vengeance for their part in the revolt once the foreign mercenaries were paid and sent home. They also persuaded the combined mercenary armies to revolt against Carthage, and various Libyan towns and cities to back the revolt. What had been a hotly contested "labour dispute" exploded into a full-scale revolt.

Heavily outmatched in terms of troops, money, and supplies, an unprepared Carthage fared poorly in the initial engagements of the war, especially under the generalship of Hanno the Great. Hamilcar Barca, general from the campaigns in Sicily, was given supreme command, and eventually defeated the rebels in 237 BC.

The war had repercussions for Carthage, both internally, and internationally. Internally, the victory of Hamilcar Barca greatly enhanced the prestige and power of the Barcid family, whose most famous member, Hannibal, would lead Carthage in the Second Punic War. Internationally, Rome used the "invitation" of the mercenaries that had captured Sardinia to occupy the island. The seizure of Sardinia and the outrageous extra indemnity fuelled resentment in Carthage. The loss of Sardinia, along with the earlier loss of Sicily meant that Carthage's traditional source of wealth, its trade, was now severely compromised, forcing them to look for a new source of wealth. This led Hamilcar, together with his son-in-law Hasdrubal and his son Hannibal to establish a power base in Hispania, outside Rome's sphere of influence, which later became the source of wealth and manpower for Hannibal's initial campaigns in the Second Punic War.

Result: Decisive Carthaginian victory

Territorial changes: Roman annexation of Sardinia and Corsica

Rome: The Punic Wars - II: The Second Punic War Begins - Extra History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lf0-Y...

Second Punic War - Referred to as The Hannibalic War or The War against Hannibal - (218 - 201 BC)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_...

- Antagonists - Carthage and Rome

- Called the Punic Wars because Rome's name for Carthaginians was Poeni, derived from Poenici (earlier form of Punici, a reference to the founding of Carthage by Phoenician settlers

- Hannibal lay siege of Saguntum - Iberian city - loyal to Rome - conflict instigation

- Most costly traditional battles of human history

- Initiated by Rome - marked by Hannibal's overland journey and crossing the Alps into Italy, also in Iberia at Carthago Nova and in Africa

- Some of the major battles: Trebia, Trasimene, Cannae, Carthage Nova, Ilipa, Zama, Metaurus as well as the Battle of the Rhone Crossing, Ebro River, Cissa

- Known strategically for Hannibal's crossing of the Alps with elephants and for Fabian strategy

Rome: The Punic Wars - III: The Second Punic War Rages On - Extra History

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wT_re...

Rome: The Punic Wars - IV: The Conclusion of the Second Punic War - Extra History

Hannibal put an end to the Second Punic War. Scipio's stringent terms of surrender were to:

a) hand over all warships and elephants

b) not make war without permission of Rome

c) pay Rome 10,000 talents over the next 50 years.

The terms included an additional, difficult proviso:

d) should armed Carthaginians cross a border the Romans drew in the dirt, it automatically meant war with Rome.

This meant that the Carthaginians could be put in a position where they might not be able to defend their own interests.

https://youtu.be/McT1H-NVCMQ

The Phoenician Carthage - The Roman Holocaust - The Third Punic War - ended with the destruction of Carthage and it people.

The Third Punic War (Latin: Tertium Bellum Punicum) (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage and the Roman Republic.

This war was a much smaller engagement than the two previous Punic Wars and focused on Tunisia, mainly on the Siege of Carthage, which resulted in the complete destruction of the city, the annexation of all remaining Carthaginian territory by Rome, and the death or enslavement of the entire Carthaginian population. The Third Punic War ended Carthage's independent existence.

Video - https://youtu.be/fn4EtY8pVnI

Downfall of the Carthaginian Empire

Lost to Rome in the First Punic War (264BC – 241BC) - Teal

Won after the First Punic War, lost in the Second Punic War - Green

Lost in the Second Punic War (218BC – 201BC) - Lighter Blue

Conquered by Rome in the Third Punic War (149BC – 146BC) - Purple

by

by

Adrian Goldsworthy

Adrian Goldsworthy

message 8:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 19, 2015 09:04PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

message 9:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 05:22PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

We will also deal with the Macedonian Wars that Rome was fighting too - which happened during the Punic Wars because the Macedonians aligned themselves with Carthage.

Polybius was an upper class Achaean who was exiled due to these wars and taken off to Italy.

The Macedonian Wars - Spend some time understanding these wars going on during the time of Polybius. Cicero came later.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedon...

Source: Wikipedia

The Macedonian Wars - Part One

https://youtu.be/Grb-THFjNYc

First Macedonian War - (214 - 205 BC)

- Caused by the fact that during the Second Punic War - Philip V of Macedon allied himself with Hannibal

- Conflict was only skirmishes to keep Macedon busy while Rome was fighting Hannibal

- Ended with Treaty of Phoenice (205 BC)

- Opened the way for Roman military intervention in Macedon

Second Macedonian War - 200 BC – 197 BC

- The Second Macedonian War was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. The result was the defeat of Philip who was forced to abandon all his possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. During their intervention, and although the Romans declared the "freedom of the Greeks" against the rule from the Macedonian kingdom, the war marked a significant stage in increasing Roman intervention in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean which would eventually lead to their conquest of the entire region.

- In 204 BC King Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt died, leaving the throne to his six-year-old son Ptolemy V.

- Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus the Great of the Seleucid Empire decided to exploit the weakness of the young king by taking Ptolemaic territory for themselves and they signed a secret pact defining spheres of interest. Philip first turned his attention to the independent Greek city states in Thrace and near the Dardanelles. His success at taking cities such as Kios worried the states of Rhodes and Pergamon who also had interests in the area.

- In 201 BC, Philip launched a campaign in Asia Minor, besieging the Ptolemaic city of Samos and capturing Miletus. Again, this disconcerted Rhodes and Pergamon and Philip responded by ravaging the territory of the latter.

- Philip then invaded Caria but the Rhodians and Pergamonians successfully blockaded his fleet in Bargylia, forcing him to spend the winter with his army in a country which offered very few provisions.

- At this point, although they appeared to have the upper hand, Rhodes and Pergamon still feared Philip so much that they sent an appeal to the fast rising powerful state of the Mediterranean: Rome.

- Rome had just emerged victorious from the Second Punic War against Carthage.

- Up to this point Rome had taken very little interest in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean. The First Macedonian War against Philip V had been over the issue of Illyria and was resolved by the Peace of Phoenice in 205 BC. Very little in Philip's recent actions in Thrace and Asia Minor could be said to concern the Roman Republic directly. Nevertheless, the Romans listened to the appeal from Rhodes and Pergamon and sent a party of three ambassadors to investigate matters in Greece. The ambassadors found very little enthusiasm for a war against Philip until they reached Athens.

Here they met King Attalus I of Pergamon and diplomats from Rhodes. At the same time, Athens declared war on Macedon and Philip sent a force to invade Attica. The Roman ambassadors held a meeting with the Macedonian general and urged Macedon to leave the Greek cities in peace, singling out Athens, Rhodes, Pergamon, and the Aetolian League as now Roman allies and thus free from Macedonian influence and to come to an arrangement with Rhodes and Pergamon to adjudicate damages from the latest war. The Macedonian general evacuated Athenian territory and handed the Roman ultimatum to his master Philip.

-Philip, who had managed to slip past the blockade and arrive back home, rejected the Roman ultimatum out of hand. He renewed his attack on Athens and began another campaign in the Dardanelles, besieging the important city of Abydus. Here, in the autumn of 200 BC, a Roman ambassador reached him with a second ultimatum, urging him not to attack any Greek state or to seize any territory belonging to Ptolemy and to go to arbitration with Rhodes and Pergamon. It was obvious that Rome was now intent on making war on Philip and at the very same time the ambassador was delivering the second ultimatum, a Roman force was disembarking in Illyria. Philip's protests that he was not in violation of any of the terms of the Peace of Phoenice he had signed with Rome were in vain.

Polybius reports that during the siege of Abydus, Philip had grown impatient and sent a message to the besieged that the walls would be stormed and that if anybody wished to commit suicide or surrender they had 3 days to do so. The citizens promptly killed all the women and children of the city, threw their valuables into the sea and fought to the last man. This story illustrates the reputation for atrocities that Philip had earned by this time during his efforts at expanding Macedonian power and influence through the conquest of other Greek cities.

- Publius Sulpicius Galba made little headway against Philip and his successor, Publius Villius, had to deal with a mutiny among his own men. In 198 BC, Villius handed command over to Titus Quinctius Flamininus, who would prove a very different kind of general.

- Seeing things were going Rome's way, Philip's few remaining allies abandoned him (with the exception of Acarnania) and he was forced to raise an army of 25,000 mercenaries. The legions of Titus confronted and defeated Philip at the Aous, However the decisive encounter came at Cynoscephalae in Thessaly in June 197 BC, when the legions of Flamininus defeated Philip's Macedonian phalanx. Philip was forced to sue for peace on Roman terms.

- The Peace of Flamininus

An armistice was declared and peace negotiations were held in the Vale of Tempe. Philip agreed to evacuate the whole of Greece and relinquish his conquests in Thrace and Asia Minor. Flamininus' allies in the Aetolian League also made further territorial claims of their own against Philip but Flamininus refused to back them. The treaty was sent to Rome for ratification. The Senate added terms of its own: Philip must pay a war indemnity and surrender his navy (although his army was untouched). In 196, peace was finally agreed and at the Isthmian Games that year Flamininus proclaimed the liberty of the Greeks to general rejoicing of those who were attending the Games. Nevertheless, the Romans kept garrisons in key strategic cities which had belonged to Macedon – Corinth, Chalcis and Demetrias – and the legions were not completely evacuated until 194.

Seleucid War (192 to 188 BC)

- With Egypt and Macedonia now weakened, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly aggressive and successful in its attempts to conquer the entire Greek world.

- When Rome pulled out of Greece at the end of the Second Macedonian War, they (and their allies) thought they had left behind a stable peace. However, by weakening the last remaining check on Seleucid expansion, they left behind the opposite. Now not only did Rome's allies against Philip seek a Roman alliance against the Seleucids, but Philip himself even sought an alliance with Rome.

- The situation was made worse by the fact that Hannibal was now a chief military advisor to the Seleucid emperor, and the two were believed to be planning for an outright conquest not just of Greece, but of Rome also. The Seleucids were much stronger than the Macedonians had ever been, given that they controlled much of the former Persian Empire, and by this point had almost entirely reassembled Alexander the Great's former empire.

- Fearing the worst, the Romans began a major mobilization, all but pulling out of recently pacified Spain and Gaul. They even established a major garrison in Sicily in case the Seleucids ever got to Italy. This fear was shared by Rome's Greek allies, who had largely ignored Rome in the years after the Second Macedonian War, but now followed Rome again for the first time since that war. A major Roman-Greek force was mobilized under the command of the great hero of the Second Punic War, Scipio Africanus, and set out for Greece, beginning the Roman-Syrian War. After initial fighting that revealed serious Seleucid weaknesses, the Seleucids tried to turn the Roman strength against them at the Battle of Thermopylae (as they believed the 300 Spartans had done centuries earlier to the mighty Persian Empire). Like the Spartans, the Seleucids lost the battle, and were forced to evacuate Greece. The Romans pursued the Seleucids by crossing the Hellespont, which marked the first time a Roman army had ever entered Asia. The decisive engagement was fought at the Battle of Magnesia, resulting in a complete Roman victory. The Seleucids sued for peace, and Rome forced them to give up their recent Greek conquests. Though they still controlled a great deal of territory, this defeat marked the beginning of the end of their empire, as they were to begin facing increasingly aggressive subjects in the east (the Parthians) and the west (the Greeks). Their empire disintegrated into a rump over the course of the next century, when it was eclipsed by Pontus. Following Magnesia, Rome pulled out of Greece again, assuming (or hoping) that the lack of a major Greek power would ensure a stable peace, though it did the opposite.

Third Macedonian War (172 to 168 BC)

- Upon Philip's death in Macedon (179 BC), his son, Perseus of Macedon, attempted to restore Macedon's international influence, and moved aggressively against his neighbors.

When Perseus was implicated in an assassination plot against an ally of Rome, the Senate declared the third Macedonian War.

Initially, Rome did not fare well against the Macedonian forces, but in 168 BC, Roman legions smashed the Macedonian phalanx at the Battle of Pydna.

Convinced now that the Greeks (and therefore the rest of the world) would never have peace if Greece was left alone yet again, Rome decided to establish its first permanent foothold in the Greek world. The Kingdom of Macedonia was divided by the Romans into four client republics. Even this proved insufficient to ensure peace, as Macedonian agitation continued

Fourth Macedonian War (150 to 148 BC)

- The Fourth Macedonian War, fought from 150 BC to 148 BC, was fought against a Macedonian pretender to the throne who was again destabilizing Greece by attempting to re-establish the old Kingdom.

- The Romans swiftly defeated the Macedonians at the Second battle of Pydna. In response, the Achaean League in 146 BC mobilized for a new war against Rome.

- This is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War, and was noted for its short duration and its timing right after the fall of Macedonia. Until this time, Rome had only campaigned in Greece in order to fight Macedonian forts, allies or clients. Rome was hopeful as Rome had triumphed against far stronger and larger opponents, the Roman legion having proved its supremacy over the Macedonian phalanx.

Source: Wikipedia

by Duncan Head

by Duncan Head

by

by

Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson

Polybius was an upper class Achaean who was exiled due to these wars and taken off to Italy.

The Macedonian Wars - Spend some time understanding these wars going on during the time of Polybius. Cicero came later.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedon...

Source: Wikipedia

The Macedonian Wars - Part One

https://youtu.be/Grb-THFjNYc

First Macedonian War - (214 - 205 BC)

- Caused by the fact that during the Second Punic War - Philip V of Macedon allied himself with Hannibal

- Conflict was only skirmishes to keep Macedon busy while Rome was fighting Hannibal

- Ended with Treaty of Phoenice (205 BC)

- Opened the way for Roman military intervention in Macedon

Second Macedonian War - 200 BC – 197 BC

- The Second Macedonian War was fought between Macedon, led by Philip V of Macedon, and Rome, allied with Pergamon and Rhodes. The result was the defeat of Philip who was forced to abandon all his possessions in southern Greece, Thrace and Asia Minor. During their intervention, and although the Romans declared the "freedom of the Greeks" against the rule from the Macedonian kingdom, the war marked a significant stage in increasing Roman intervention in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean which would eventually lead to their conquest of the entire region.

- In 204 BC King Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt died, leaving the throne to his six-year-old son Ptolemy V.

- Philip V of Macedon and Antiochus the Great of the Seleucid Empire decided to exploit the weakness of the young king by taking Ptolemaic territory for themselves and they signed a secret pact defining spheres of interest. Philip first turned his attention to the independent Greek city states in Thrace and near the Dardanelles. His success at taking cities such as Kios worried the states of Rhodes and Pergamon who also had interests in the area.

- In 201 BC, Philip launched a campaign in Asia Minor, besieging the Ptolemaic city of Samos and capturing Miletus. Again, this disconcerted Rhodes and Pergamon and Philip responded by ravaging the territory of the latter.

- Philip then invaded Caria but the Rhodians and Pergamonians successfully blockaded his fleet in Bargylia, forcing him to spend the winter with his army in a country which offered very few provisions.

- At this point, although they appeared to have the upper hand, Rhodes and Pergamon still feared Philip so much that they sent an appeal to the fast rising powerful state of the Mediterranean: Rome.

- Rome had just emerged victorious from the Second Punic War against Carthage.

- Up to this point Rome had taken very little interest in the affairs of the eastern Mediterranean. The First Macedonian War against Philip V had been over the issue of Illyria and was resolved by the Peace of Phoenice in 205 BC. Very little in Philip's recent actions in Thrace and Asia Minor could be said to concern the Roman Republic directly. Nevertheless, the Romans listened to the appeal from Rhodes and Pergamon and sent a party of three ambassadors to investigate matters in Greece. The ambassadors found very little enthusiasm for a war against Philip until they reached Athens.

Here they met King Attalus I of Pergamon and diplomats from Rhodes. At the same time, Athens declared war on Macedon and Philip sent a force to invade Attica. The Roman ambassadors held a meeting with the Macedonian general and urged Macedon to leave the Greek cities in peace, singling out Athens, Rhodes, Pergamon, and the Aetolian League as now Roman allies and thus free from Macedonian influence and to come to an arrangement with Rhodes and Pergamon to adjudicate damages from the latest war. The Macedonian general evacuated Athenian territory and handed the Roman ultimatum to his master Philip.

-Philip, who had managed to slip past the blockade and arrive back home, rejected the Roman ultimatum out of hand. He renewed his attack on Athens and began another campaign in the Dardanelles, besieging the important city of Abydus. Here, in the autumn of 200 BC, a Roman ambassador reached him with a second ultimatum, urging him not to attack any Greek state or to seize any territory belonging to Ptolemy and to go to arbitration with Rhodes and Pergamon. It was obvious that Rome was now intent on making war on Philip and at the very same time the ambassador was delivering the second ultimatum, a Roman force was disembarking in Illyria. Philip's protests that he was not in violation of any of the terms of the Peace of Phoenice he had signed with Rome were in vain.

Polybius reports that during the siege of Abydus, Philip had grown impatient and sent a message to the besieged that the walls would be stormed and that if anybody wished to commit suicide or surrender they had 3 days to do so. The citizens promptly killed all the women and children of the city, threw their valuables into the sea and fought to the last man. This story illustrates the reputation for atrocities that Philip had earned by this time during his efforts at expanding Macedonian power and influence through the conquest of other Greek cities.

- Publius Sulpicius Galba made little headway against Philip and his successor, Publius Villius, had to deal with a mutiny among his own men. In 198 BC, Villius handed command over to Titus Quinctius Flamininus, who would prove a very different kind of general.

- Seeing things were going Rome's way, Philip's few remaining allies abandoned him (with the exception of Acarnania) and he was forced to raise an army of 25,000 mercenaries. The legions of Titus confronted and defeated Philip at the Aous, However the decisive encounter came at Cynoscephalae in Thessaly in June 197 BC, when the legions of Flamininus defeated Philip's Macedonian phalanx. Philip was forced to sue for peace on Roman terms.

- The Peace of Flamininus

An armistice was declared and peace negotiations were held in the Vale of Tempe. Philip agreed to evacuate the whole of Greece and relinquish his conquests in Thrace and Asia Minor. Flamininus' allies in the Aetolian League also made further territorial claims of their own against Philip but Flamininus refused to back them. The treaty was sent to Rome for ratification. The Senate added terms of its own: Philip must pay a war indemnity and surrender his navy (although his army was untouched). In 196, peace was finally agreed and at the Isthmian Games that year Flamininus proclaimed the liberty of the Greeks to general rejoicing of those who were attending the Games. Nevertheless, the Romans kept garrisons in key strategic cities which had belonged to Macedon – Corinth, Chalcis and Demetrias – and the legions were not completely evacuated until 194.

Seleucid War (192 to 188 BC)

- With Egypt and Macedonia now weakened, the Seleucid Empire became increasingly aggressive and successful in its attempts to conquer the entire Greek world.

- When Rome pulled out of Greece at the end of the Second Macedonian War, they (and their allies) thought they had left behind a stable peace. However, by weakening the last remaining check on Seleucid expansion, they left behind the opposite. Now not only did Rome's allies against Philip seek a Roman alliance against the Seleucids, but Philip himself even sought an alliance with Rome.

- The situation was made worse by the fact that Hannibal was now a chief military advisor to the Seleucid emperor, and the two were believed to be planning for an outright conquest not just of Greece, but of Rome also. The Seleucids were much stronger than the Macedonians had ever been, given that they controlled much of the former Persian Empire, and by this point had almost entirely reassembled Alexander the Great's former empire.

- Fearing the worst, the Romans began a major mobilization, all but pulling out of recently pacified Spain and Gaul. They even established a major garrison in Sicily in case the Seleucids ever got to Italy. This fear was shared by Rome's Greek allies, who had largely ignored Rome in the years after the Second Macedonian War, but now followed Rome again for the first time since that war. A major Roman-Greek force was mobilized under the command of the great hero of the Second Punic War, Scipio Africanus, and set out for Greece, beginning the Roman-Syrian War. After initial fighting that revealed serious Seleucid weaknesses, the Seleucids tried to turn the Roman strength against them at the Battle of Thermopylae (as they believed the 300 Spartans had done centuries earlier to the mighty Persian Empire). Like the Spartans, the Seleucids lost the battle, and were forced to evacuate Greece. The Romans pursued the Seleucids by crossing the Hellespont, which marked the first time a Roman army had ever entered Asia. The decisive engagement was fought at the Battle of Magnesia, resulting in a complete Roman victory. The Seleucids sued for peace, and Rome forced them to give up their recent Greek conquests. Though they still controlled a great deal of territory, this defeat marked the beginning of the end of their empire, as they were to begin facing increasingly aggressive subjects in the east (the Parthians) and the west (the Greeks). Their empire disintegrated into a rump over the course of the next century, when it was eclipsed by Pontus. Following Magnesia, Rome pulled out of Greece again, assuming (or hoping) that the lack of a major Greek power would ensure a stable peace, though it did the opposite.

Third Macedonian War (172 to 168 BC)

- Upon Philip's death in Macedon (179 BC), his son, Perseus of Macedon, attempted to restore Macedon's international influence, and moved aggressively against his neighbors.

When Perseus was implicated in an assassination plot against an ally of Rome, the Senate declared the third Macedonian War.

Initially, Rome did not fare well against the Macedonian forces, but in 168 BC, Roman legions smashed the Macedonian phalanx at the Battle of Pydna.

Convinced now that the Greeks (and therefore the rest of the world) would never have peace if Greece was left alone yet again, Rome decided to establish its first permanent foothold in the Greek world. The Kingdom of Macedonia was divided by the Romans into four client republics. Even this proved insufficient to ensure peace, as Macedonian agitation continued

Fourth Macedonian War (150 to 148 BC)

- The Fourth Macedonian War, fought from 150 BC to 148 BC, was fought against a Macedonian pretender to the throne who was again destabilizing Greece by attempting to re-establish the old Kingdom.

- The Romans swiftly defeated the Macedonians at the Second battle of Pydna. In response, the Achaean League in 146 BC mobilized for a new war against Rome.

- This is sometimes referred to as the Achaean War, and was noted for its short duration and its timing right after the fall of Macedonia. Until this time, Rome had only campaigned in Greece in order to fight Macedonian forts, allies or clients. Rome was hopeful as Rome had triumphed against far stronger and larger opponents, the Roman legion having proved its supremacy over the Macedonian phalanx.

Source: Wikipedia

by Duncan Head

by Duncan Head by

by

Victor Davis Hanson

Victor Davis Hanson

message 10:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 09:32AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Hannibal of Carthage

Often regarded as one of the greatest military strategists in history, Hannibal would later be considered one of the greatest generals of antiquity, together with Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Scipio, and Pyrrhus of Epirus.

Plutarch states that, when questioned by Scipio as to who was the greatest general, Hannibal is said to have replied either Alexander or Pyrrhus, then himself, or, according to another version of the event, Pyrrhus, Scipio, then himself.

Military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge once famously called Hannibal the "father of strategy", because his greatest enemy, Rome, came to adopt elements of his military tactics in its own strategic arsenal. This praise has earned him a strong reputation in the modern world, and he was regarded as a great strategist by men like Napoleon Bonaparte.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannibal

This is a novel about Hannibal:

by

by

David Anthony Durham

David Anthony Durham

Other books:

by

by

Adrian Goldsworthy

Adrian Goldsworthy

Great Courses: Hannibal

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-qY2...

Source: Youtube

Often regarded as one of the greatest military strategists in history, Hannibal would later be considered one of the greatest generals of antiquity, together with Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Scipio, and Pyrrhus of Epirus.

Plutarch states that, when questioned by Scipio as to who was the greatest general, Hannibal is said to have replied either Alexander or Pyrrhus, then himself, or, according to another version of the event, Pyrrhus, Scipio, then himself.

Military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge once famously called Hannibal the "father of strategy", because his greatest enemy, Rome, came to adopt elements of his military tactics in its own strategic arsenal. This praise has earned him a strong reputation in the modern world, and he was regarded as a great strategist by men like Napoleon Bonaparte.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannibal

This is a novel about Hannibal:

by

by

David Anthony Durham

David Anthony DurhamOther books:

by

by

Adrian Goldsworthy

Adrian GoldsworthyGreat Courses: Hannibal

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F-qY2...

Source: Youtube

message 11:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 09:34AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Publius Cornelius Scipio

The son of Lucius Cornelius Scipio, he was the father of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (the elder), and of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus.

Publius Cornelius Scipio (died 211 BC) was a general and statesman of the Roman Republic.

A member of the Cornelia gens, Scipio served as consul in 218 BC, the first year of the Second Punic War. He sailed with his army from Pisa with the intention of confronting Hannibal in Hispania.[1] Stopping at Massilia (today Marseille) to replenish his supplies, he was shocked to discover that Hannibal's army had moved from Hispania and was crossing the Rhône.[1] Scipio disembarked his army and marched to confront Hannibal, who, by now, had moved on. Returning to the fleet, he entrusted the command of his army to his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus and sent him off to Hispania to carry on with the originally intended mission. Scipio returned to Italy to take command of the troops fighting in Cisalpine Gaul.[2]

On his return to Italy, he advanced at once to meet Hannibal. In a sharp cavalry engagement near the Ticinus, a tributary of the Po river, he was defeated and severely wounded. In December of the same year, he again witnessed the complete defeat of the Roman army at the Trebia, when his fellow consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus allegedly insisted on fighting against his advice. [The earliest historical source was by the Greek historian Polybius, who became an intimate of Scipio's grandson and was seemingly biased in favour of the Scipio family. The other major account was written in the following century by the Roman historian Livy, who also expressed bias in favour of certain aristocratic families.][3]

Despite the military defeats, he still retained the confidence of the Roman people: his term of command was extended and the following year found him in Hispania with his brother Calvus, winning victories over the Carthaginians and strengthening Rome's position in the Iberian peninsula.

He continued the Iberian campaigns until 211, when he was killed during the defeat of his army at the upper Baetis river by the Carthaginians and their iberian allies under Indibilis and Mandonius.

That same year, Calvus and his army were destroyed at Ilorci near Carthago Nova. The details of these campaigns are not completely known, but it seems that the ultimate defeat and death of the two Scipiones was due to the desertion of the Celtiberians, who were bribed by Hasdrubal Barca, Hannibal's brother.

Source: Wikipedia

Great Courses - Publius Cornelius Scipio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1H1FS...

He viewed Rome as "res publica" - or literally "the people's thing.

Res Publia - a balanced constitution - a balance between the essential elements of government.

Democratic element was simply the broad based public support.

He believed that there had to be "an aristocratic element" - Guidance of the commonwealth by a small body of "the best" - (the Senate)

Monarchial Element - strong executive authority - (the Consuls)

Two Consuls - the No vote of one will always override the Yes vote of another

The Consuls were elected annually.

Libertas - liberty was the overriding quality - only means freedom under the law and they did not believe in equality. To be a citizen you must serve in the army - so women were not citizens. Every Roman had to serve in the army up to the age of 46. Every Roman had to serve at least 16 years between the ages of 20 and 46. Every Roman during time of crisis had to serve 20 years. And before he could even hold public office he had to serve a minimum of 10 years in the Roman army.

Sources: Wikipedia and the Great Courses on youtube

by

by

Susan Wise Bauer

Susan Wise Bauer

The son of Lucius Cornelius Scipio, he was the father of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (the elder), and of Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus.

Publius Cornelius Scipio (died 211 BC) was a general and statesman of the Roman Republic.

A member of the Cornelia gens, Scipio served as consul in 218 BC, the first year of the Second Punic War. He sailed with his army from Pisa with the intention of confronting Hannibal in Hispania.[1] Stopping at Massilia (today Marseille) to replenish his supplies, he was shocked to discover that Hannibal's army had moved from Hispania and was crossing the Rhône.[1] Scipio disembarked his army and marched to confront Hannibal, who, by now, had moved on. Returning to the fleet, he entrusted the command of his army to his brother Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus and sent him off to Hispania to carry on with the originally intended mission. Scipio returned to Italy to take command of the troops fighting in Cisalpine Gaul.[2]

On his return to Italy, he advanced at once to meet Hannibal. In a sharp cavalry engagement near the Ticinus, a tributary of the Po river, he was defeated and severely wounded. In December of the same year, he again witnessed the complete defeat of the Roman army at the Trebia, when his fellow consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus allegedly insisted on fighting against his advice. [The earliest historical source was by the Greek historian Polybius, who became an intimate of Scipio's grandson and was seemingly biased in favour of the Scipio family. The other major account was written in the following century by the Roman historian Livy, who also expressed bias in favour of certain aristocratic families.][3]

Despite the military defeats, he still retained the confidence of the Roman people: his term of command was extended and the following year found him in Hispania with his brother Calvus, winning victories over the Carthaginians and strengthening Rome's position in the Iberian peninsula.

He continued the Iberian campaigns until 211, when he was killed during the defeat of his army at the upper Baetis river by the Carthaginians and their iberian allies under Indibilis and Mandonius.

That same year, Calvus and his army were destroyed at Ilorci near Carthago Nova. The details of these campaigns are not completely known, but it seems that the ultimate defeat and death of the two Scipiones was due to the desertion of the Celtiberians, who were bribed by Hasdrubal Barca, Hannibal's brother.

Source: Wikipedia

Great Courses - Publius Cornelius Scipio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1H1FS...

He viewed Rome as "res publica" - or literally "the people's thing.

Res Publia - a balanced constitution - a balance between the essential elements of government.

Democratic element was simply the broad based public support.

He believed that there had to be "an aristocratic element" - Guidance of the commonwealth by a small body of "the best" - (the Senate)

Monarchial Element - strong executive authority - (the Consuls)

Two Consuls - the No vote of one will always override the Yes vote of another

The Consuls were elected annually.

Libertas - liberty was the overriding quality - only means freedom under the law and they did not believe in equality. To be a citizen you must serve in the army - so women were not citizens. Every Roman had to serve in the army up to the age of 46. Every Roman had to serve at least 16 years between the ages of 20 and 46. Every Roman during time of crisis had to serve 20 years. And before he could even hold public office he had to serve a minimum of 10 years in the Roman army.

Sources: Wikipedia and the Great Courses on youtube

by

by

Susan Wise Bauer

Susan Wise Bauer

message 12:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 20, 2015 08:44PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

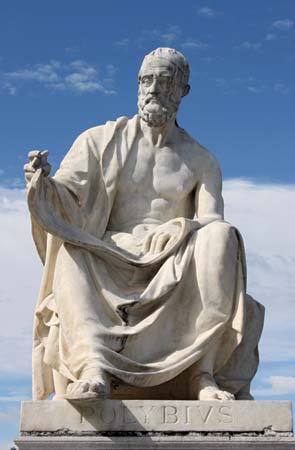

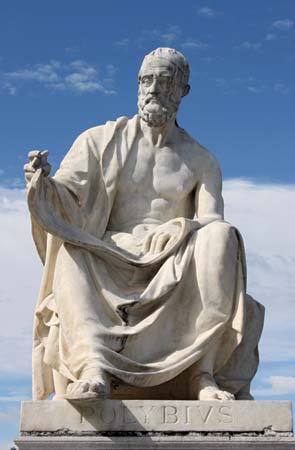

Polybius

Polybius, (Born c. 200 BC, Megalopolis, Arcadia, Greece—died C 118), Greek statesman and historian who wrote of the rise of Rome to world prominence.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/P...

Polybius, Greek historian, Roman Analyst

Polybius lived circa 200-118 B.C. In his work, the Histories, he chronicled Roman history from 220-146 B.C.

His work included an analysis of the three principle forms of government, monarchy (rule by one), aristocracy (rule by few) and democracy (rule by many).

He observed that in each of the three, an unavoidable degeneration took place over time.

A monarch would become a tyranny. An aristocracy would become an oligarchy. A democracy ultimately degenerated into mob-rule. In each, this took place by a gradual decline that he calls anacyclosis or “political revolution”.

Hereditary monarchs did not possess the qualities of their predecessors. Aristocrats over time became the idle rich and unconnected to the people. Pure democracy leads to a tyranny of the majority and disenfranchisement of a significant minority.

Polybius believed that Republican Rome avoided this endless cycle by establishing a mixed constitution, a single state with elements of all three forms of government at once: monarchy (in the form of its elected executives, the consuls), aristocracy (as represented by the Senate), and democracy (in the form of the popular assemblies, such as the Comitia Centuriata).

Polybius credited the success of Rome to having mixed these forms of government, and separating power among the various groups of society, giving every group a stake and every individual incentive to contribute.

Polybius’ observations and writings began the evolutionary development of the separation of powers concept.

Source: Separation of Powers in the US Constitution: 1800 Years of Thought - See more at: http://www.shestokas.com/constitution...

Other source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Polybius as an Historian

As you read Polybius, you will notice that his historical method involves the following aspects:

• An insistence on a world-view and international perspective

• Interrogating of a wide range of sources, notably public archives and eyewitnesses

• An insistence that history should ‘tell the truth’

• A focus on narrative history which explains how and why

• A focus on individuals and what they achieved – the 'heroes of history'

• His belief in τύχη (divine fate)

• What he calls πραγματικῆς ἱστορίας (history which teaches you 'how-to-live')

• What he calls ‘digressions’ to discuss geography, art, science and moral issues.

1. Strengths of Polybius

• He had lived through many of the events he was writing about

• He made a real effort to work from as many sources as possible

• He interviewed eyewitnesses, including many important people

• He assessed his sources' reliability, and rejected biased sources

• He was an expert on politics and warfare (and interested in technology)

• He took great care to get his geography right, and visited the places he wrote about

• His Histories were a genuine work of synthesis

• He sought the TRUTH.

2. Weaknesses of Polybius

• He had lived through many of the events he was writing about

• He believed his eyewitnesses

• He wrote for Greeks

• He was biased for the Romans, and especially for the Scipios (his patrons)

• He wrote to draw out the 'moral' of the story, and to convey the 'lesson for life'

• Although he criticized made-up speeches, he sometimes made up speeches!

Source: http://www.johndclare.net/AncientHist...

Polybius, (Born c. 200 BC, Megalopolis, Arcadia, Greece—died C 118), Greek statesman and historian who wrote of the rise of Rome to world prominence.

http://www.britannica.com/biography/P...

Polybius, Greek historian, Roman Analyst

Polybius lived circa 200-118 B.C. In his work, the Histories, he chronicled Roman history from 220-146 B.C.

His work included an analysis of the three principle forms of government, monarchy (rule by one), aristocracy (rule by few) and democracy (rule by many).

He observed that in each of the three, an unavoidable degeneration took place over time.

A monarch would become a tyranny. An aristocracy would become an oligarchy. A democracy ultimately degenerated into mob-rule. In each, this took place by a gradual decline that he calls anacyclosis or “political revolution”.

Hereditary monarchs did not possess the qualities of their predecessors. Aristocrats over time became the idle rich and unconnected to the people. Pure democracy leads to a tyranny of the majority and disenfranchisement of a significant minority.

Polybius believed that Republican Rome avoided this endless cycle by establishing a mixed constitution, a single state with elements of all three forms of government at once: monarchy (in the form of its elected executives, the consuls), aristocracy (as represented by the Senate), and democracy (in the form of the popular assemblies, such as the Comitia Centuriata).

Polybius credited the success of Rome to having mixed these forms of government, and separating power among the various groups of society, giving every group a stake and every individual incentive to contribute.

Polybius’ observations and writings began the evolutionary development of the separation of powers concept.

Source: Separation of Powers in the US Constitution: 1800 Years of Thought - See more at: http://www.shestokas.com/constitution...

Other source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Polybius as an Historian

As you read Polybius, you will notice that his historical method involves the following aspects:

• An insistence on a world-view and international perspective

• Interrogating of a wide range of sources, notably public archives and eyewitnesses

• An insistence that history should ‘tell the truth’

• A focus on narrative history which explains how and why

• A focus on individuals and what they achieved – the 'heroes of history'

• His belief in τύχη (divine fate)

• What he calls πραγματικῆς ἱστορίας (history which teaches you 'how-to-live')

• What he calls ‘digressions’ to discuss geography, art, science and moral issues.

1. Strengths of Polybius

• He had lived through many of the events he was writing about

• He made a real effort to work from as many sources as possible

• He interviewed eyewitnesses, including many important people

• He assessed his sources' reliability, and rejected biased sources

• He was an expert on politics and warfare (and interested in technology)

• He took great care to get his geography right, and visited the places he wrote about

• His Histories were a genuine work of synthesis

• He sought the TRUTH.

2. Weaknesses of Polybius

• He had lived through many of the events he was writing about

• He believed his eyewitnesses

• He wrote for Greeks

• He was biased for the Romans, and especially for the Scipios (his patrons)

• He wrote to draw out the 'moral' of the story, and to convey the 'lesson for life'

• Although he criticized made-up speeches, he sometimes made up speeches!

Source: http://www.johndclare.net/AncientHist...

message 13:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 20, 2015 08:57PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

How to Study Polybius

http://www.slideshare.net/dposkerhill...

Source: in Slideshare

Short Video:

https://www.goodreads.com/videos/9054...

http://www.slideshare.net/dposkerhill...

Source: in Slideshare

Short Video:

https://www.goodreads.com/videos/9054...

message 14:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 06:06AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What do you think of some of Polybius beliefs?

both by Polybius (no photo)

both by Polybius (no photo)

by Brian C. McGing (no photo)

by Brian C. McGing (no photo)

both by Polybius (no photo)

both by Polybius (no photo) by Brian C. McGing (no photo)

by Brian C. McGing (no photo)

message 15:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 20, 2015 09:09PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

More of Polybius quotes:

“There is no witness so dreadful, no accuser so terrible as the conscience that dwells in the heart of every man.”

―Polybius

“Those who know how to win are much more numerous than those who know how to make proper use of their victories.”

―Polybius

Polybius

“All things are subject to decay and change...”

―Polybius

Polybius

“This is a sworn treaty made between us, Hannibal... and Xenophanes the Athenian... in the presence of all the gods who possess Macedonia and the rest of Greece.”

―Polybius

“The government will take the fairest of names, but the worst of realities — mob rule.”

―Polybius

“There is no witness so dreadful, no accuser so terrible as the conscience that dwells in the heart of every man.”

―Polybius

“Those who know how to win are much more numerous than those who know how to make proper use of their victories.”

―Polybius

Polybius

“All things are subject to decay and change...”

―Polybius

Polybius

“This is a sworn treaty made between us, Hannibal... and Xenophanes the Athenian... in the presence of all the gods who possess Macedonia and the rest of Greece.”

―Polybius

“The government will take the fairest of names, but the worst of realities — mob rule.”

―Polybius

message 16:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 06:08AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Scipio Africanus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africans (236–183 BC), also known as Scipio the African, Scipio Africanus-Major, Scipio Africanus the Elder, and Scipio the Great, is renowned as one of the greatest generals, not only of ancient Rome, but of all time.

His main achievements were during the Second Punic War where he is best known for defeating Hannibal at the final battle at Zama, one of the feats that earned him the agnomen Africans, as well as recognition as one of the finest commanders in military history.

Source: "Isis priest01 pushkin" by user:shakko - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

by

by

B.H. Liddell Hart

B.H. Liddell Hart

by Richard Miles (no photo)

by Richard Miles (no photo)

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africans (236–183 BC), also known as Scipio the African, Scipio Africanus-Major, Scipio Africanus the Elder, and Scipio the Great, is renowned as one of the greatest generals, not only of ancient Rome, but of all time.

His main achievements were during the Second Punic War where he is best known for defeating Hannibal at the final battle at Zama, one of the feats that earned him the agnomen Africans, as well as recognition as one of the finest commanders in military history.

Source: "Isis priest01 pushkin" by user:shakko - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons - https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

by

by

B.H. Liddell Hart

B.H. Liddell Hart by Richard Miles (no photo)

by Richard Miles (no photo)

message 17:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 06:37AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Hamilcar Barca

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair. The name Hamilcar was a common name for Carthaginian men.

Video:

Source: History.com

Hamilcar Barca and the Punic Wars

Hamilcar Barca, father of the great Carthaginian general Hannibal, meets with disaster during a campaign in the Punic Wars.

His surname meant "lightning".

He was sad to see Corsica and Sardinia after hundreds of years of Carthaginian rule be now in the Roman domain. He went to Spain for a new source of manpower and income and resources to make Carthage great again and break away from domination.

Video: http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

by Barry Linton (no photo)

by Barry Linton (no photo)

Source: Wikipedia

Hamilcar Barca or Barcas was a Carthaginian general and statesman, leader of the Barcid family, and father of Hannibal, Hasdrubal and Mago. He was also father-in-law to Hasdrubal the Fair. The name Hamilcar was a common name for Carthaginian men.

Video:

Source: History.com

Hamilcar Barca and the Punic Wars

Hamilcar Barca, father of the great Carthaginian general Hannibal, meets with disaster during a campaign in the Punic Wars.

His surname meant "lightning".

He was sad to see Corsica and Sardinia after hundreds of years of Carthaginian rule be now in the Roman domain. He went to Spain for a new source of manpower and income and resources to make Carthage great again and break away from domination.

Video: http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

by Barry Linton (no photo)

by Barry Linton (no photo)Source: Wikipedia

message 18:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 06:13AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V (Greek: Φίλιππος Ε΄) (238–179 BC) was King of Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man. A dashing and courageous warrior, he was inevitably compared to Alexander the Great and was nicknamed the beloved of all Greece (Greek: "ἐρώμενος τῶν Ἑλλήνων") because he became, as Polybius put it, "...the beloved of all Hellenes for his charitable inclination

Philip V of Macedon (179 - 238 BC)

Philip was King of Macedon from 221 to 179 BC, son of King Demetrius II, ascended the throne on the death of his tutor, Antigonus Doson.

Gained fame from a war (220-217 BC) in which, together with the Achaean League, defeated an alliance formed by the Aetolian League, Sparta and Elis; then he allied with Demetrius of Pharos, dangerous Illyrian Prince and, most of all, enemy of Rome.

The victories of the Carthaginian General Hannibal in Italy convinced Philip to conclude an alliance with Carthage in 215 BC, hoping, in this way, to secure for himself the Roman possessions in Illyria. The agreement, however, bring on a long conflict with Rome, known as Macedonian war, which eventually imposed Roman rule in Greece.

Philip then devoted himself to the reconstruction of his reign reorganizing finances, opening some mines and improving the defenses of Northern frontiers. But the continuous intervention of Rome against Macedonis, following claims of neighbouring States, convinced Philip that the Romans wanted to annex his realm. So in 184-183 BC, and again in 181 BC, he tried, with no success, to extend its dominance in the Balkans.

by Frank William Walbank (no photo)

by Frank William Walbank (no photo)

Philip V (Greek: Φίλιππος Ε΄) (238–179 BC) was King of Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man. A dashing and courageous warrior, he was inevitably compared to Alexander the Great and was nicknamed the beloved of all Greece (Greek: "ἐρώμενος τῶν Ἑλλήνων") because he became, as Polybius put it, "...the beloved of all Hellenes for his charitable inclination

Philip V of Macedon (179 - 238 BC)

Philip was King of Macedon from 221 to 179 BC, son of King Demetrius II, ascended the throne on the death of his tutor, Antigonus Doson.

Gained fame from a war (220-217 BC) in which, together with the Achaean League, defeated an alliance formed by the Aetolian League, Sparta and Elis; then he allied with Demetrius of Pharos, dangerous Illyrian Prince and, most of all, enemy of Rome.

The victories of the Carthaginian General Hannibal in Italy convinced Philip to conclude an alliance with Carthage in 215 BC, hoping, in this way, to secure for himself the Roman possessions in Illyria. The agreement, however, bring on a long conflict with Rome, known as Macedonian war, which eventually imposed Roman rule in Greece.

Philip then devoted himself to the reconstruction of his reign reorganizing finances, opening some mines and improving the defenses of Northern frontiers. But the continuous intervention of Rome against Macedonis, following claims of neighbouring States, convinced Philip that the Romans wanted to annex his realm. So in 184-183 BC, and again in 181 BC, he tried, with no success, to extend its dominance in the Balkans.

by Frank William Walbank (no photo)

by Frank William Walbank (no photo)

message 19:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 20, 2015 10:35PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

What happened at the end of the Fourth Macedonian War?

Polybius blames the demagogues of the cities of the league for inspiring the population into a suicidal war. Nationalist stirrings and the idea of triumphing against superior odds motivated the league into this rash decision. The Achaean League was swiftly defeated, and, as an object lesson, Rome utterly destroyed the city of Corinth in 146 BC, the same year that Carthage was destroyed.

After nearly a century of constant crisis management in Greece, which always led back to internal instability and war when Rome pulled out, Rome decided to divide Macedonia into two new Roman provinces, Achaea and Epirus.

Source: Wiipedia

Polybius blames the demagogues of the cities of the league for inspiring the population into a suicidal war. Nationalist stirrings and the idea of triumphing against superior odds motivated the league into this rash decision. The Achaean League was swiftly defeated, and, as an object lesson, Rome utterly destroyed the city of Corinth in 146 BC, the same year that Carthage was destroyed.

After nearly a century of constant crisis management in Greece, which always led back to internal instability and war when Rome pulled out, Rome decided to divide Macedonia into two new Roman provinces, Achaea and Epirus.

Source: Wiipedia

message 20:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 05:46AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Other Topics for Discussion

Folks we are open - please feel free to talk about the similarities and differences between modern democracy and the Roman model.

Discuss any of Polybius quotes, life story or beliefs.

What did you think of the founding fathers article and what we have to thank the Romans for?

Also, please feel free to discuss any high points in Chapter Four of Ryan's book that you would like to begin a conversation about.

Are the democracies of the world in a gradual decline that Polybius called anacyclosis or “political revolution”? Why or why not?

Folks we are open - please feel free to talk about the similarities and differences between modern democracy and the Roman model.

Discuss any of Polybius quotes, life story or beliefs.

What did you think of the founding fathers article and what we have to thank the Romans for?

Also, please feel free to discuss any high points in Chapter Four of Ryan's book that you would like to begin a conversation about.

Are the democracies of the world in a gradual decline that Polybius called anacyclosis or “political revolution”? Why or why not?

message 21:

by

Bentley, Group Founder, Leader, Chief

(last edited Sep 21, 2015 10:50AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Just came across this for all of the philosophy interested parties here:

Here is a good book - audio free: The History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell - narrator is pretty good too.

http://www.learnoutloud.com/Free-Audi...

LearnOutLoud.com Review

Cozy up by the fireplace with this free version of Bertrand Russell's classic 1945 book The History Of Western Philosophy. It's a book we've always wanted to see on audio and didn't think it was ever recorded.

But it seems someone has uploaded an out-of-print recording of it to YouTube, and has even done the service of dividing it up by chapters which, for the most part, each cover a particular philosopher.

This history of philosophy covers philosophers from the pre-Socratics to the early 20th century including chapters on such philosophical giants as Plato, Aristotle, St. Augustine, Machiavelli, Descartes, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, Friedrich Nietzsche, Karl Marx, William James, and many more great minds. So you can listen selectively to the philosophers you are interested in, or listen to the entire 22 hour audio book. It is available to stream on a playlist through YouTube.

Description

A History of Western Philosophy is a 1945 book by philosopher Bertrand Russell. A conspectus of Western philosophy from the pre-Socratic philosophers to the early 20th century, it was criticised for its over-generalization and its omissions, particularly from the post-Cartesian period, but nevertheless became a popular and commercial success, and has remained in print from its first publication.

When Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950, the book was cited as one of those that won him the award. The book provided Russell with financial security for the last part of his life.

Playlist: (It is already divided up into chapters)

https://www.youtube.com/playlist?p=PL...

by

by

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Here is a good book - audio free: The History of Western Philosophy by Bertrand Russell - narrator is pretty good too.

http://www.learnoutloud.com/Free-Audi...

LearnOutLoud.com Review