The Pickwick Club discussion

This topic is about

George Silverman's Explanation

George Silverman's Explanation

>

George Silverman's Explanation

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

A short intro post for this story as I need to get in the kitchen and deal with transforming the remains of our Thanksgiving turkey into a savory Sunday soup. :)

A short intro post for this story as I need to get in the kitchen and deal with transforming the remains of our Thanksgiving turkey into a savory Sunday soup. :)I enjoyed this story from the start, mainly because it was in first person narration from the point of view of a young boy, and this in itself reminded me of the beginnings of David Copperfield. I found it sad because George, at this point, is just an innocent boy who is unable to think much of anything beyond wondering if he will have enough food and warmth in order to even survive. He doesn't wonder why his life is the way it is, why he is stuck in a cellar, what else is out in the world, why he ended up with parents who died while he was young. He forges on, and after being transferred into a more stable situation for his well-being, he moves on from thinking about his own well-being, to the well-being of the people around him - Sylvia, for example.

Tristram asks, what makes George the man he is? I can only guess that the fact that he mainly spent his youth by himself, struggling to survive, waiting day to day for his parents to come home with hopefully some food, is a large part of the reason. He learned to be patient, and grateful to simply have warmth, food, and health. And possibly because he lived in this manner himself, when he finally was in a situation where he did not have to worry about the basic necessities, this patience and worry for the necessities transferred to those people around him.

The quotations that Tristram offers us focus on the central recurring image of the story which is that George Silverman is always in the shadows, always looking towards a door, or looking out a window. In the beginning of the novel George watches as his mother's form unfolds to his watching eyes as she comes down the dark and gloomy stairs. Later he watches Sylvia from the shadows. Later still he falls in love with Adelina Fareway, only to retreat into the shadows so that Granville Wharton can meet, court, and finally marry her. George sees himself as worthless, not any better than the rats at Hoghton Tower who "hid themselves close together in the dark ... at the bottom of one of the smaller pits of broken staircase."

The quotations that Tristram offers us focus on the central recurring image of the story which is that George Silverman is always in the shadows, always looking towards a door, or looking out a window. In the beginning of the novel George watches as his mother's form unfolds to his watching eyes as she comes down the dark and gloomy stairs. Later he watches Sylvia from the shadows. Later still he falls in love with Adelina Fareway, only to retreat into the shadows so that Granville Wharton can meet, court, and finally marry her. George sees himself as worthless, not any better than the rats at Hoghton Tower who "hid themselves close together in the dark ... at the bottom of one of the smaller pits of broken staircase."The sad irony of the story is that George believes his constant attempts and acts of isolation are the best way to gain acceptance and his best way to integrate himself into civilization; others, of course, read his acts of seclusion as proof of his inhospitality.

To directly answer Tristram's first question I believe George has a very weak self-esteem and believes he is always tainted with that miasma -an entire world of social ills - that killed his parents. His first order of survival is to withdraw from the world as his way of gaining acceptance to live within the world.

Tristram and Linda are so right. There is much to discuss in this story. Time for dinner, however. More to come.

Oh yes, Peter. I like your answer to Tristram's first question much better than my attempt. George's low self-esteem most definitely played into what made him a man. And it is sad that his attempt at protecting others and thinking of their well-being only further distanced himself from other people and gave them the wrong idea of his inner character.

Oh yes, Peter. I like your answer to Tristram's first question much better than my attempt. George's low self-esteem most definitely played into what made him a man. And it is sad that his attempt at protecting others and thinking of their well-being only further distanced himself from other people and gave them the wrong idea of his inner character. It seemed that George's decision to remain in the shadows was only a continuation of him remaining in the cellar during his boyhood.

Why did he not just renounce Adelina but introduce her to his other student instead?

When I read of the student, he reminded me somewhat of George himself, if only for the fact that he was making his way in the world on his own after the death of his parents. I wonder if George also saw a bit of himself in this student, and so if George was not a good enough match for Adelina, then the next best thing in George's heart would be for Adelina to be married to this student (sorry, I don't remember the student's name at the moment). Even though the student did not have a fortune, he was a good man, and that should be enough for a good marriage. Lack of money should not be a barrier to two people enjoying a life together.

George's renouncing of Adelina was painful to read. It was the final act of his weirdly self-imposed and misplaced altruism. Looking back at the story it is interesting to trace his relationships with the four central females in his life.

George's renouncing of Adelina was painful to read. It was the final act of his weirdly self-imposed and misplaced altruism. Looking back at the story it is interesting to trace his relationships with the four central females in his life.George Silverman's impoverished beginning is introduced to the reader as his mother descends their hovel's staircase. Dickens carefully crafts the first few pages to illustrate George's caring nature, and the scene where he offers his dying mother sips of water is powerful. There is no question that George has the capacity to be caring and loving. He is much more than a "worldly little devil" but this criticism is internalized into his mind and psyche and taints his opinion of himself for life.

The second female George is connected with is Sylvia, but his feelings for her, like his physical person, he keeps from her in order to protect her. He is much like a knight with his lady. Dickens's irony is that George, as a knight, can only protect his lady if he stays away from her. Indeed, Sylvia encourages George to join her to celebrate a birthday. George, however, in order to serve her, must remain in the shadows and only watch.

The third female and second female adult of importance in George's life is Lady Fareway. She is nothing more than an opportunistic leech who turns George into a low paid cleric and secretary. Thus, George's second encounter with a mother figure is one of wealth rather than the first, who was his poverty-stricken mother. George finds no emotional bond with her. Lady Fareway does have a daughter, however, and here Dickens teases the readers with the possibility that George will be able to break out of his negative, self-imposed shyness. What occurs is that George is unable to deal with the "diseased corner[s]" of his mind. Once again, rather than seizing the opportunity to embrace love, George chooses to deny his own possible happiness and so he guides Adeline's heart to Granville Wharton. In this final act of self-denial George Silverman both figuratively and literally sacrifices his own personal happiness on the alter of marriage as he joins Adeline and Granville together.

Dickens's pairing of George Silverman with the four women demonstrate how he was constantly unable to have any lasting positive relationship with a woman. The death of his mother, the youthful naive sacrifice of his feelings for Sylvia, the manner in which Lady Fareway perverts her professional relationship with him to the final emotional blow of sacrificing the love of a woman who does love him, George Silverman is, perhaps, one of Dickens's most memorable male characters.

Peter wrote: "Once again, rather than seizing the opportunity to embrace love, George chooses to deny his own possible happiness and so he guides Adeline's heart to Granville Wharton. In this final act of self-denial George Silverman both figuratively and literally sacrifices his own personal happiness on the alter of marriage as he joins Adeline and Granville together."

Peter wrote: "Once again, rather than seizing the opportunity to embrace love, George chooses to deny his own possible happiness and so he guides Adeline's heart to Granville Wharton. In this final act of self-denial George Silverman both figuratively and literally sacrifices his own personal happiness on the alter of marriage as he joins Adeline and Granville together."This is a very good way of putting it, Peter. George Silverman finds his satisfaction in an act of self-denial. Nevertheless, could he not also simply have kept Adelina as a student, enjoyed her company and then let her go? Enabling her to make the acquaintance of and making her fall in love with Granville seems to me to have been a way of vicariously loving her. After all, he shapes Granville's spirit more and more according to the fashion of his own spirit. It is as though he derives, I'm using the word again, vicarious pleasure from Granville's falling in love with and being loved by Adelina. And this is very creepy, in my opinion.

It is probably because, as Peter said, Silverman has a problem with his image of himself. Just look at what he says about his own station in comparison to Adelina's.

His quest for a virtuous and selfless life leaves him, as Peter said, in the shadows, a passive onlooker on human relationships and personal fulfilment and commitment. Others might do him injustice when regarding him as a morose recluse, but what probably can be said of him is that his inner life is somewhat impoverished. In a way, he is a bit like Miss Wade: Where Miss Wade suspected other people of humiliating her and where she craved for the exclusive attachment of some other person (e.g. the other girl she went to school with), Mr. Silverman suspects himself of egoism and sacrifices any claim to human relations for the sake of not appearing worldly or mean. And yet - in the case of Adelina, he could not simply forbear interfering with her life.

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Once again, rather than seizing the opportunity to embrace love, George chooses to deny his own possible happiness and so he guides Adeline's heart to Granville Wharton. In this final..."

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "Once again, rather than seizing the opportunity to embrace love, George chooses to deny his own possible happiness and so he guides Adeline's heart to Granville Wharton. In this final..."Yes. Miss Wade and George Silverman. Two very unique character profiles and psyches to explore.

Your question of how and if George Silverman's life parallels Dickens is very important and opens up many doors for exploration. Since this story was the last complete work of Dickens it makes this story even more intriguing and important to investigate. In terms of Dickens's evolution as a novelist the creation of George Silverman places him in a very different universe than Mr Pickwick.

If, for a moment, we exclude GE and OMF, Dickens ability to penetrate and then portray the human condition in all its strengths and weaknesses is fully displayed. We see in the movement from Pickwick to Silverman the movement from a flat, cardboard-like external man in Pickwick to a penetrating analysis of the internal persona of Silverman. As Pickwick is a display of all that is innocent and good in the world, Silverman shows the results of how a society, a family, and an individual's own self-image all combine to create human sorrow and misery.

I do think that George Silverman's Explanation can be read as a portal into understanding Dickens own personal life at the time of the writing. I also think that in this story we see how far Dickens has evolved in his own writing ability in terms of the development of character and plot. Best not to say too much more in order to avoid spoilers with GE, but hopefully we can return to this discussion at the end of GE. There is, I believe, much to mine yet.

George reminded me of my father. Well, he wasn't like my father, but he brought him to my mind. My dad grew up during the depression in a house full of children and neither of his parents work. He told me once that he never remembers seeing his mother out of bed. He used to go in to see her sometimes, but most of the time she was too sick to talk and died when he was seven. Of breast cancer in case you were wondering, she died in 1924 so that may have been before they could do much for cancer I don't know. I've also found it creepy that my dad doesn't remember her out of bed but he has two younger siblings, does that mean she was having children while dying of cancer? I don't know. Also, his father was an alcoholic who never seemed to be able to hold down a job for long, and for a long time didn't bother to try. Dad was the first of his family to graduate from high school, everyone else had to quit after eighth grade to go to work - there were eight kids all together. Anyway, what I'm getting at is this, he seemed to have a very awful childhood, and yet unlike George he almost never mentioned it. The only reason I had a hint of any of it was hearing other family members talk about it and you had to almost hold him captive to get him to answer any questions about it. That's one reason George made me think of him, while George tells us all about his childhood, if it were up to dad we'd know almost nothing of his.

George reminded me of my father. Well, he wasn't like my father, but he brought him to my mind. My dad grew up during the depression in a house full of children and neither of his parents work. He told me once that he never remembers seeing his mother out of bed. He used to go in to see her sometimes, but most of the time she was too sick to talk and died when he was seven. Of breast cancer in case you were wondering, she died in 1924 so that may have been before they could do much for cancer I don't know. I've also found it creepy that my dad doesn't remember her out of bed but he has two younger siblings, does that mean she was having children while dying of cancer? I don't know. Also, his father was an alcoholic who never seemed to be able to hold down a job for long, and for a long time didn't bother to try. Dad was the first of his family to graduate from high school, everyone else had to quit after eighth grade to go to work - there were eight kids all together. Anyway, what I'm getting at is this, he seemed to have a very awful childhood, and yet unlike George he almost never mentioned it. The only reason I had a hint of any of it was hearing other family members talk about it and you had to almost hold him captive to get him to answer any questions about it. That's one reason George made me think of him, while George tells us all about his childhood, if it were up to dad we'd know almost nothing of his.Another thing about George that reminded me of dad was his telling a story for no particular reason than to just tell it. Although in the case of dad it usually was just random comments not stories. But during this story I kept wondering how it would end, would we learn a lesson like, "if you are ever in charge of a child when his parents have died, don't swindle him". Or "if a couple comes to you wanting to get married without parents permission, just tell them to elope". Or I was waiting for a happy ending, no, he doesn't get the girl he loves, but later finds another woman who is his soul mate and now has been happily married to her for 40 years, or something like that. But there was nothing like that, he just told his story without being asked about it, and it just ended. There was no reason to tell it, just like dad used to do now and then, we could be discussing when to start Christmas decorating, what to have for dinner, whatever, and dad would suddenly say "I used to have a horse named Old Bull, I sure did love that horse, why I drove the Indians out of the valley when we first settled here with Old Bull", and when asked what happened to Old Bull he would reply "I had to eat him when we were lost in the desert." Ok, dad thanks for that information. One of the oddest things was we were sitting in the living room one day, just dad and I, both reading, and he suddenly says "Do you know I think I've slept with every girl in this valley at one time". To which I replied something like "Wow dad, now what are you going to do? You'll have to start in the next valley." I'm not sure why but George reminded me of all this.

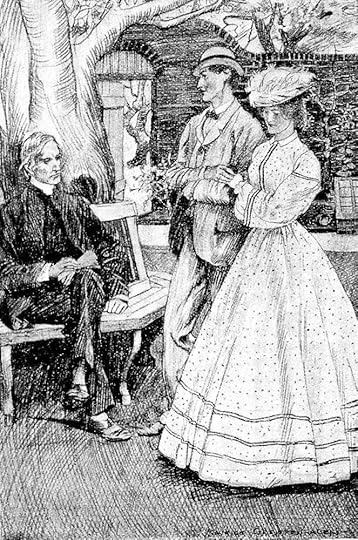

This is the only illustration I've found so far for this story but I'm still looking. It is by Maurice Greiffenhagen, someone I hadn't heard of before.

This is the only illustration I've found so far for this story but I'm still looking. It is by Maurice Greiffenhagen, someone I hadn't heard of before.

"These Two Came Before Me Hand In Hand"

Maurice Greiffenhagen

1898

Dickens's George Silverman's Explanation in the The Fireside Edition

Text Illustrated:

"So passed more than another year; every day a year in its number of my mixed impressions of grave pleasure and acute pain; and then these two, being of age and free to act legally for themselves, came before me hand in hand (my hair being now quite white), and entreated me that I would unite them together. "And indeed, dear tutor," said Adelina, "it is but consistent in you that you should do this thing for us, seeing that we should never have spoken together that first time but for you, and that but for you we could never have met so often afterwards.

The whole of which was literally true; for I had availed myself of my many business attendances on, and conferences with, my lady, to take Mr. Granville to the house, and leave him in the outer room with Adelina.

I knew that my lady would object to such a marriage for her daughter, or to any marriage that was other than an exchange of her for stipulated lands, goods, and moneys. But looking on the two, and seeing with full eyes that they were both young and beautiful; and knowing that they were alike in the tastes and acquirements that will outlive youth and beauty; and considering that Adelina had a fortune now, in her own keeping; and considering further that Mr. Granville, though for the present poor, was of a good family that had never lived in a cellar in Preston; and believing that their love would endure, neither having any great discrepancy to find out in the other, — I told them of my readiness to do this thing which Adelina asked of her dear tutor, and to send them forth, husband and wife, into the shining world with golden gates that awaited them."

Thanks Kim for hunting down this illustration. When I re-read the text with the illustration above I started to think. When George writes "I knew that my lady would object to such a marriage for her daughter, or any other marriage that was other than an exchange of her for stipulated lands, goods, and moneys" I could not help but think how stark the contrast was between Mrs Fareway and George. Mrs Fareway sees her daughter as a mere commodity to be sold and recorded as any other transaction George has recorded as her accountant. On the other hand, to George, Adeline is anything but a commodity. Adeline represents a pure ideal of love. That George chooses not to openly admit his love for Adeline may speak of the tragic flaw of George believing he is an unworthy person, but, just as importantly, it is a display of altruism. George chooses to bring Adeline and Granville together and to officiate at their marriage. George does understand love and his refusal to follow his heart costs him dearly.

Thanks Kim for hunting down this illustration. When I re-read the text with the illustration above I started to think. When George writes "I knew that my lady would object to such a marriage for her daughter, or any other marriage that was other than an exchange of her for stipulated lands, goods, and moneys" I could not help but think how stark the contrast was between Mrs Fareway and George. Mrs Fareway sees her daughter as a mere commodity to be sold and recorded as any other transaction George has recorded as her accountant. On the other hand, to George, Adeline is anything but a commodity. Adeline represents a pure ideal of love. That George chooses not to openly admit his love for Adeline may speak of the tragic flaw of George believing he is an unworthy person, but, just as importantly, it is a display of altruism. George chooses to bring Adeline and Granville together and to officiate at their marriage. George does understand love and his refusal to follow his heart costs him dearly. Mrs Fareway erupts with accusations of George financially profiting from the marriage which is in line with her believing the world is one of deals and commerce rather than one of compassion and commitment.

Kim, thanks for that illustration. The name Maurice Greiffenhagen does not sound familiar to me, either, but when I look at the people in the illustration, I'm not quite sure whether I'd like to change that. I take it the man sitting on the bench is supposed to be George Silverman - and he does not at all match the George Silverman the story conjured up before my mental eye. The Silverman I pictured was reticent and shy but also kindly and caring whereas the person in the picture seems morose and forbiddingly distant. The young couple does not look much more likable either, though.

Kim, thanks for that illustration. The name Maurice Greiffenhagen does not sound familiar to me, either, but when I look at the people in the illustration, I'm not quite sure whether I'd like to change that. I take it the man sitting on the bench is supposed to be George Silverman - and he does not at all match the George Silverman the story conjured up before my mental eye. The Silverman I pictured was reticent and shy but also kindly and caring whereas the person in the picture seems morose and forbiddingly distant. The young couple does not look much more likable either, though.I'd like to have your Dad heard telling one or two of his stories, from what you shared with us here. It's especially the Old Bull story with its rather homely common-sense ending of eating the horse that made my imagination do somersaults ;-) Thanks for sharing those memories!

When looking at George Silverman's history of self-sacrifice and renouncing the girls he liked or loved - Sylvia and Adelina respectively - I could not help thinking of Dickens. Did he see himself in George Silverman? After all, he fell in love - let's assume that - with Ellen Ternan, but the morals of his time did not allow him to live that love out publicly. He would have considered that a very great sacrifice, wouldn't he?

When looking at George Silverman's history of self-sacrifice and renouncing the girls he liked or loved - Sylvia and Adelina respectively - I could not help thinking of Dickens. Did he see himself in George Silverman? After all, he fell in love - let's assume that - with Ellen Ternan, but the morals of his time did not allow him to live that love out publicly. He would have considered that a very great sacrifice, wouldn't he?Then there are the references to the Preston cellar: They reminded me of Dickens's childhood trauma connected with his weeks in the blacking factory when his father was imprisoned for debt. Maybe the experience of poverty, loneliness and disorientation enabled Dickens to picture how Silverman would have felt.

Another thing I found interesting was the pains Silverman took in order to find a right beginning to his story. You said he was telling his story for no apparent reason. I would have said that his reason was to justify himself against any potential accusation that might be connected with his name: He does not address his explanation at anyone in particular - as becomes clear at the end - but yet he feels it necessary to make a clean breast of his inner motives and to prove that he did not act for selfish and base reasons. It seems as though Silverman has never managed to escape from his feelings of guilt that were instilled within him by his hard-nosed mother. He is so afraid of being considered a "worldly little devil" after all.

Tristram wrote: "When looking at George Silverman's history of self-sacrifice and renouncing the girls he liked or loved - Sylvia and Adelina respectively - I could not help thinking of Dickens. Did he see himself ..."

Tristram wrote: "When looking at George Silverman's history of self-sacrifice and renouncing the girls he liked or loved - Sylvia and Adelina respectively - I could not help thinking of Dickens. Did he see himself ..."Yes. It is always tempting to find threads of Dickens's personal life in the world of his novels. We know that Dickens went to great lengths to hide his youthful personal history from everyone (thank heavens for Forester). Like you, Tristram, I believe in the case of Dickens there is justification in this belief. In GE we will see Dickens directly name a place from his personal history. In our upcoming Christmas read we will see two sisters ... .

I am no psychiatrist or Freudian but there is simply too much evidence in his novels not to be very aware of his personal life when we read his fictional worlds.

I think the evidence of such links increases more and more as we have read into his later mature novels.

As Kim asked me to stand in for her this week, I am going to do the introduction for our short story George Silverman’s Explanation, which was one of the last stories Dickens ever wrote. In fact, it was written after his last complete novel, Our Mutual Friend, and it is a story very dark in tone.

The story is told from the point of view of a first person narrator, the eponymous George Silverman, who leads the reader through decisive situations in his life. He starts with sombre childhood memories of having been brought up in a damp and insalubrious cellar in Preston, and when he thinks of his mother, this comes to his mind:

He apparently rarely has the opportunity to leave this cellar-hole, and with a pang he notices that his mother scolds him for being a “worldly little devil”, just because he is hungry and thirsty and feels cold – and, with the honesty of a child, voices these needs. When his parents die of a fever, he is found by the neighbours and they don’t take very kindly towards him, thinking him unfeeling, when he talks about being hungry and cold when his parents have just died.

A Mr. Hawkyard, however, appears on the scene, who claims to have been a friend of George’s grandfather, a man of some property. The grandfather died not long ago, but according to Hawkyard, or Brother Hawkyard, as that sanctimonious swindler wants to be called, he did not leave anything to his family, and it is just because Hawkyard is such a good Christian that he volunteers to look after the orphan and give him an education. Later, George Silverman cannot help feeling that he has been swindled out of his property by Hawkyard but he soon reproaches himself for these “worldly” thoughts and writes a letter in which he exonerates Hawkyard from any suspicion of ill-doing. Such suspicions were raised by Brother Gimblet, a fellow-brother of Hawkyard’s, as an attempt at blackmailing Hawkyard into giving him a share in the loot.

But we have to go back a few years in the biography of George Silverman: As a child, he is sent to a farm in order to recover from his years in the cellar. On that farm, there is a young girl called Sylvia, whom he likes very much. Nevertheless, he keeps away from her for fear of passing the fever his parents died of on to her – a fear that does not seem very well-founded at all. Not being allowed to tell the farmers that his parents died of a fever, nobody on the farm can understand Silverman’s reticence, and they take him to be a sullen and morose loner.

When Silverman later goes to school and gets a scholarship because of his diligence and scholarly excellence, he still does not make friends with anyone but is always bent on doing in duty in order not to be considered a “worldly little devil”. All in all, his trauma of being regarded as a depraved materialistic “devil” makes him stand aloof from human society as such:

One day – he has already become a tutor at the university – he is offered a rectorate by the mother of one of his former students, a Lady Fareway, who has – as her son tells Silverman, and as the reader soon learns – quite a hand for doing business. She offers Silverman a rectorate with a yearly income of 200 £ and at the same time talks him into doing private secretary work for her and teaching her daughter Adelina, a young woman of high intellect. Silverman, in order not to seem worldly, accepts these modest terms and … he falls in love with Adelina. Of course, he considers himself as infinitely below Adelina and her family, and he now enables his other student, Mr. Wharton, to make Adelina’s acquaintance. By and by, the two young people fall in love with each other, and Silverman weds them without Lady Fareway’s assent, and even without her knowledge.

When he tells his benefactress about the wedding, the Lady flies into a fury and accuses him of having performed the wedding for worldly reasons, being bribed into it by the upstart Wharton. She makes him resign the rectorate and also tries to give him a bad name in the country, but even though there are hard times before him, Adelina and her husband stand by him and eventually more and more people realize that such worldly behaviour would be out of character with George Silverman. The story ends like this:

I was quite intrigued with this story because here – like in Miss Wade’s tale from Little Dorrit - Dickens uses the first person narrator to great effect and with flawless consistency. I would even see a connection between the two stories because in both stories we have a narrator whose soul-life is out of balance in a way. Therefore my questions:

What do you think made George Silverman the man he is?

Do you consider him an entirely unworldly person, or is his bevahiour flawed in a way?

Why did he not just renounce Adelina but introduce her to his other student instead?

And why did he shape Mr. Wharton’s intellect in a way he knew would please and fascinate Adelina?

And last, not least:

Do you see any parallels in the life of George Silverman and that of Charles Dickens, his creator? Or would-be parallels?

I am looking forward to a lively discussion of this truly fascinating story.