World, Writing, Wealth discussion

Storytelling and Writing Craft

>

Crafting Action Scenes #5 - Combat Mechanics

If your MC is some sort of expert, then the fight should be short. Usually the first properly landed blow decides the winner. Two real-life examples from one of my business partners, who in his younger days lived in Japan and was rated in the top ten at karate.

If your MC is some sort of expert, then the fight should be short. Usually the first properly landed blow decides the winner. Two real-life examples from one of my business partners, who in his younger days lived in Japan and was rated in the top ten at karate. 1. Two green berets walked into the dojo one day and challenged those in there. The number one politely told them to go away. They didn't, so number one got up, shook his head and gave them a last warning. That was rejected. Within ten seconds he sat down again, the two green berets were on the floor, each with two broken legs. It is doubtful the American even saw what happened.

2. One of these Japanese got into an elevator in New York and four others also got in. Apparently they tried to mug him while the elevator was going up. When he got to his level, he exited, each of the muggers lying on the floor with various broken bones.

Real fights with experts are very brief. It is very difficult to continue fighting with a broken bone or a dislocated joint. I know professional wrestling goes on for quite a while, but they are choreographed to avoid real danger blows, and of course the wrestlers are in very good body condition.

Combat scenes are hard to describe. As Ian said, you want to capture the speed at which a fight normally happens. You also want to give enough technical detail to make it convincing, yet avoid baffling the reader.

Combat scenes are hard to describe. As Ian said, you want to capture the speed at which a fight normally happens. You also want to give enough technical detail to make it convincing, yet avoid baffling the reader.I've read poor versions of fight scenes where the author seems to be giving instructions on how to perform a new yoga pose! : )

It's sometimes worth doing a bit of 'method-writing'. I don't know which type of combat you want to describe, but taking a few martial art/ boxing lessons at a reputable club will give you valuable insight. Ditto actually going and firing a rifle, if it's a military scene you're working on.

That said, if you're too busy writing, I'd recommend the 'Orphan X' series of novels by Gregg Hurwitz for inspiration. That guy has obviously done in-depth research. Some of the Wilbur Smith novels are extremely visceral/ convincing, and, in the fantasy genre, David Gemmell always knew how to write a great sword fight.

By your post, it sounds as if your characters may be performing 'Matrix'-style, supernatural feats in combat? So think point-of-view. Imagine the thoughts going through a skilled veteran's head when he suddenly realises he's outclassed.

Combat scenes can be more gripping if the reader doesn't know everything that's going on. In real-life, sniper fire comes out of nowhere; the mugger relies on the element of surprise.

If you have a squad, the sniper gives you a chance for a longer tenser scene. The first you know of it is someone going down. Is he dead or should he be dragged to safety? Who risks the next bullet. You all take cover, then the problem, where is the sniper? What are you all going to do about him, bearing in mind he may well move? Stalking, then finding him can take quite a few high octane pages.

If you have a squad, the sniper gives you a chance for a longer tenser scene. The first you know of it is someone going down. Is he dead or should he be dragged to safety? Who risks the next bullet. You all take cover, then the problem, where is the sniper? What are you all going to do about him, bearing in mind he may well move? Stalking, then finding him can take quite a few high octane pages.

My concept of Combat Mechanics is more as follows.

My concept of Combat Mechanics is more as follows.[1] I had a major sequence of scenes occurring in a warehouse with a pier jutting onto a river. I drew up a floor plan of the warehouse and the pier.

The key issues I was looking at managing were as follows.

[a] Can a Blackhawk helicopter land on the pier, what about it's rotors, is there enough space. Because one does.

[b] I've got super-powered humans vs super-powered vamps (but the issues remain at normal speed), The vamps attack - how long will it take them to get from one end of the warehouse to the other.

I explicitly ended up with a 200 yard long warehouse precisely to give me enough room to have a couple of battles in the warehouse, before the superior numbers of the vamps pushed the heroes out onto the pier. If the warehouse was shorter, the vamps are on them before much can happen...

Where this comes from for me is that I've read fight scenes where I will visualize it one way, and then suddenly - from the text - a major character is suddenly 'on the other physical side,' of the fight.

The experience is jarring, and I lose the flow of the story, while I go, - "That doesn't make sense..."

The point of paying careful attention to 'combat mechanics,' is about making sure the whole fight proceeds in a seamless manner that presents no "jarring," of the reader's disbelief.

In my current work, I had a single fighter vs a 6 (+2 reinforcements) man force, in a corridor with a couple of archways leading off and an open doorway at the end.

I outlined the floor plan on A4 paper, and printed off ten copies, I then labeled all the players on the first sheet, and stepped through the battle using a page for each step.

In this way, I was accounting for everyone and when I wrote the scenes (there were 3 in total for this fight as I swap POV between the opponents) they flowed smoothly and read well.

When I speak of 'combat mechanics,' I talking in the broadest sense of how the fight, the personnel, the equipment and physical environment all fit together to provide a seamless experience for the reader.

I agree you have to have the "terrain" fixed in your mind. One mistake I have seen is on battles on a ship - everyone darts around and covers so much room no ship would be big enough for them.

I agree you have to have the "terrain" fixed in your mind. One mistake I have seen is on battles on a ship - everyone darts around and covers so much room no ship would be big enough for them.For the more complicated combat situations, I usually try to draw a map of what is there, and sometimes more a floor plan with a different one for different levels, although in a building all levels have to have the same dimensions (obviously).

The other thing I think has to be taken care of is cover. It has to be specified before it is needed, or it has to be reasonably plausibly there. Thus a theatre can have a ticket office, or and upstairs gallery without stating it, but if stuff appears in a combat just because you need something, I think it lacks plausibility. A person can take cover behind something that is known to be there, and that makes it even look planned if he has previously moved there, but if it just appears, I think it lacks plausibility.

I'm studying Graeme's action scenes and I hope to emulate them in mine.

I'm studying Graeme's action scenes and I hope to emulate them in mine.Drawing a map and sequencing the action is also another solid technique I'll use for fights that are larger than duels.

Graeme wrote: "Three dimensional space ship combat would present some interesting problems."

Graeme wrote: "Three dimensional space ship combat would present some interesting problems."I have done that several times, most in "Scaevola's Triumph". Five of them were simulated training exercises, so these each started with the same scenario. All my space battles started with a solar system, so that gives a point of reference, and they all focus more on the overall strategy. One effectively refought the battle of Cannae, (or, if you prefer, the third battle for Kharkhov) only in 3D and with space ships. By describing the strategy, the reader knows where everything is at the start, then as the MC starts the action, the opponent has to make the first response with their ships.

The real trick is to take advantage of "terrain" to generate a surprise. You may think "surprise" in space is not possible, because your instruments can see everything, but that is far from the truth.

The next problem is to try to get the physics more or less right. If you want your ships to turn, you must have some form of lateral propulsion. There is no need to describe the ships in detail, but you have to avoid making them turn like aircraft because there is no atmosphere to generate the pressure you need.

Speaking of aircraft, I found that as far as tactics go, and remember you are not in an atmosphere, those used by the Luftwaffe on the Eastern front were worth considering. These guys that lived to write them down were in combat for about 4 years - on a "fly or die" scenario (none of these tours of duty) - and they worked it out, and interestingly, the best of those tactics will work outside an atmosphere as long as the ships can turn. They did not engage in the "dogfights" you probably imagine - they flew through the enemy, knocking them out as they went through then if necessary would re-engage. Hartmann seldom took out more than two enemy, and most of the time just one, but he ended up with about 350 kills, which leaves most other allied pilots in the dust. Of course being outnumbered he had more targets. These guys tended to fly in groups of four and they coordinated their efforts, so you have four aircraft acting as a separate entity almost.

I've dabbled in mixed martial arts over the years, and fiddled with a bit of archery, and have found that both things help when writing fight scenes.

I've dabbled in mixed martial arts over the years, and fiddled with a bit of archery, and have found that both things help when writing fight scenes.I write from the pictures inside my head, which I suspect helps to sequence the action.

Leonie is bad-ass!

Leonie is bad-ass!I'm hearing heavy understatement... typical Aussie. She can probably shoot three simultaneously thrown tennis balls out of the air with her bow and arrows.

MMA? Probably been an instructor at Swan Barracks when she lived in the West.

Graeme wrote: "Leonie is bad-ass!

Graeme wrote: "Leonie is bad-ass!I'm hearing heavy understatement... typical Aussie. She can probably shoot three simultaneously thrown tennis balls out of the air with her bow and arrows.

MMA? Probably been a..."

Um....no? 😝

I was a Vertical Rescue Instructor for the State Emergency Service, however, that's not a lot of help when writing combat scenes...

Graeme wrote: "Three dimensional space ship combat would present some interesting problems."

Graeme wrote: "Three dimensional space ship combat would present some interesting problems."I wrote a number of dogfights in Dione's War. Because of the space involved and the speed of the tiny ships, I didn't go for the movie thing where one ship closes in on another and in seconds scores a hit...the two fighters close in, fire off their shots and then take stock of their "misses" as they fly past each other, zoom, zig and zag. It required a lot of 3-dimensional thinking to picture the parties involved to make sure they were where they were supposed to be when they turn for another approach.

The thing about fight mechanics in general, is I find I really think fights through to make sure the movements are plausible. But as a reader, when I'm reading fight scene's in others' books, my mind doesn't really care if the next move is plausible after a character delivers a roundhouse kick or whatever...I don't really think that deeply about someone else's work - as long as the scene isn't ridiculous, I read through it and move on....

Hi J.J. that reminds me of a sequence of scenes I have where there are dueling gunship helicopters.

Hi J.J. that reminds me of a sequence of scenes I have where there are dueling gunship helicopters.I stepped through the action with a series of A4 sheets of paper to make sure I had the angles correct for missile shots, etc, and how they were maneuvering to bring their weapons to bear on each other.

I could have fun with that setup. Given both sides are constantly moving parts, I would take issue with the idea that one side would take out the other with a few carefully placed shots. I would more likely have them fire their missiles at each other, but they keep missing, watching the ordinance go off into some unfortunate bank office or something similar.

I could have fun with that setup. Given both sides are constantly moving parts, I would take issue with the idea that one side would take out the other with a few carefully placed shots. I would more likely have them fire their missiles at each other, but they keep missing, watching the ordinance go off into some unfortunate bank office or something similar.

In setting the scene I establish entries and exits so that distraction during the actual fight is minimised. I vary the grammar and ensure that pace destroyers such as pointless details, random thoughts and reactions, don’t break up the action. I have a good sense of visualisation so I also visualise the scene – and then check it out. The flight + fight on the Potemkin Stairs, in Odessa -A Guide to First Contact - isn't integral to the main character story but forms part of the layering in of background to the future. Once I map checked, I realised the stairs pointed in a direction I hadn't anticipated, I had to refigure things as the event had to occur there.

In setting the scene I establish entries and exits so that distraction during the actual fight is minimised. I vary the grammar and ensure that pace destroyers such as pointless details, random thoughts and reactions, don’t break up the action. I have a good sense of visualisation so I also visualise the scene – and then check it out. The flight + fight on the Potemkin Stairs, in Odessa -A Guide to First Contact - isn't integral to the main character story but forms part of the layering in of background to the future. Once I map checked, I realised the stairs pointed in a direction I hadn't anticipated, I had to refigure things as the event had to occur there. Staged battles make great video viewing but are wasteful on manpower (the great unanswered criticism of WW1 leadership, both sides); the reality is that it’s better to out manoeuvre your enemy so you don’t squander hard to replace resources. A space battle requires a place where opposing sides have a reason to congregate; a planet, a trading station, an interspecies hospital ship (yes you James White) or a mega space artefact. Most space battles I’ve read are unconvincing. I’ve done space ambushes in The Tau Device and I’ll try my hand at set space battles in due course.

Fantasy battles is a mixed bag. J.R.R. Tolkien’s battle scenes are relatively short but tension is built up in preceding chapters via a scattergun effect which delivers a sense of menace and impending doom. Robert E Howard’s Conan: fine, Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser: mostly fine; more recent works have been a bit of a let down; get a hero and a villain and you begin to gauge relative strengths from hints dropped by the author – it’s what you do – then you get to the fight and it’s a cop-out, and you feel misled. Anyway although I haven’t done a set-piece fantasy battle scene, in Brant, a stand-off between marauding mercenary companies is resolved by a contract killing… the victim being set up by magical means!

J.J. wrote: "I could have fun with that setup. Given both sides are constantly moving parts, I would take issue with the idea that one side would take out the other with a few carefully placed shots. I would mo..."

J.J. wrote: "I could have fun with that setup. Given both sides are constantly moving parts, I would take issue with the idea that one side would take out the other with a few carefully placed shots. I would mo..."Indeed.

For large scale, long duration epic battles - the best I've read are by Steven Erikson (epic fantasy) in his Malazan Book of the Fallen Series

For large scale, long duration epic battles - the best I've read are by Steven Erikson (epic fantasy) in his Malazan Book of the Fallen Series

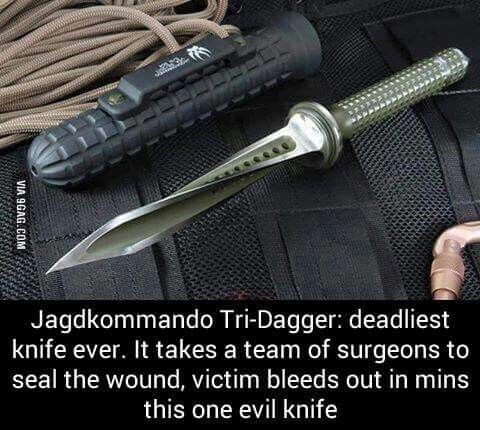

Saw this book and though if you guys!

Saw this book and though if you guys!The Writer's Guide to Weapons: A Practical Reference for Using Firearms and Knives in Fiction

Good leading question by Graeme, and many good answers. Remember that a battle may be short and involving only two combats, or long. Maybe taking place over days. And in some cases involving a wide range of resources (men and machine).

Good leading question by Graeme, and many good answers. Remember that a battle may be short and involving only two combats, or long. Maybe taking place over days. And in some cases involving a wide range of resources (men and machine).

The third battle of Karkhov took more than three months, and several armies! It would take a lot to describe that in short sentences.

The third battle of Karkhov took more than three months, and several armies! It would take a lot to describe that in short sentences.

Next to witty dialog, I love writing combat scenes. Often difficult, always rewarding! But this is one of the aspects I enjoy about the action/thriller genre, and it's many subgenres.

Next to witty dialog, I love writing combat scenes. Often difficult, always rewarding! But this is one of the aspects I enjoy about the action/thriller genre, and it's many subgenres.

Dave wrote: "But this is one of the aspects I enjoy about the action/thriller genre, and it's many subgenres. ."

Dave wrote: "But this is one of the aspects I enjoy about the action/thriller genre, and it's many subgenres. ."Indeed. Same here.

Having (a while ago) been in the Royal Marines (1969-82), one thing that I have found that applied when things started happening and which I rarely see in written descriptions is just how tunnel-visioned one can get in situations.

Having (a while ago) been in the Royal Marines (1969-82), one thing that I have found that applied when things started happening and which I rarely see in written descriptions is just how tunnel-visioned one can get in situations.In the build-up, you've got peripheral senses; the closer one gets to the point, the more one focuses on the target.

The other factor that I've noticed is time dilation. In a lot of fiction, the central character often has a clear idea of the order of events, and how long things took. That wasn't my experience.

Hi David,

Hi David,I think your points are valid.

However, how do you carry that across in narrative.

In my own writing, I often have (perhaps always) the POV character is clear about what the hell is going on (unless they are about to be killed...)

I think it would be possible to do 'fog of war,' stuff where the POV character is experiencing what is happening - and it's chaotic, and what is witnessed is not always clear.

David has a good point, BUT in fiction, I can't see how you manage time dilation. The problem is, the reader will be reading words at a constant rate. You can focus on more and more detail at the point of action, but does that give a dilation effect, or merely more detail?

David has a good point, BUT in fiction, I can't see how you manage time dilation. The problem is, the reader will be reading words at a constant rate. You can focus on more and more detail at the point of action, but does that give a dilation effect, or merely more detail?I think any given character has a clear idea of what is happening to him, to the extent of what he sees, when he sees it. In an aerial dogfight, as an example, a character will see what is in front of him, but then, maybe, suddenly finds his plane shot to pieces from behind or underneath. That is hard to be convincing. However, the problem does tend to be easier if you are writing third person past tense. It would be first person present that David's points would be extremely difficult to get right. My opinion, anyway.

It's not easy, Graeme.

It's not easy, Graeme.In my work, I've tried various things, according to the needs of the piece. For "bottom-up" POV stuff, where the POV character is one of the Tommies (by whatever name they are known), I tend to write the first draft to get the feel of the chaos and uncertainty as the underlying base of the passage. It's often totally impossible for the reader to have a clue what's going on at this stage of the writing process. That's all right, because my first objective is to get the right feel across.

Having done the first draft, I then rewrite it, adding and subtracting as necessary to enable the reader to follow the course of events, while still retaining the feel. That's the objective, any way. Whether I achieve it or not is another matter, and one that only the reader can decide.

By contrast, when I'm writing from a higher POV, I tend to not try and include the nitty-gritty details of what's happening on the ground. If the story is about the big picture, then I concentrate on the big picture.

If I knew how to convincingly convey time dilation in a story, I'd be a better writer (and possibly a richer one) than I am.

If I knew how to convincingly convey time dilation in a story, I'd be a better writer (and possibly a richer one) than I am.It's one of those situation where I can see what the problem is, but haven't yet found a convincing way of overcoming it in writing myself. For example, during the Falklands Conflict, there was a lengthy period of Yomping from San Carlos on the left-hand side of the map to Mount Harriet on the right-hand side. Several days of trudging with 150lb of kit through peat-bogs, sinking with each step to ankles or knees, and it rained constantly - except when it was snowing with the wind blowing straight off the Antarctic in winter - and the wind seemingly always in our faces. If you asked me now, I couldn't say how long we yomped for. The days just blurred into each other, and you kind of just lost track of time. We now know that people back home where getting bored because it was taking so long (including the delightful signal grumbling that we were not walking as fast as London wanted us to, reminding us that we weren't on a holiday), but it was just an indistinct blur.

Things were different once we reached Mount Harriet. Once the attack started, time moved in fits and starts. Sometimes, it moved incredibly slowly, as you weighed up and planned an approach, which felt like a quarter of an hour, but was actually less than a minute, and then having dealt with that, you blinked, and it was half an hour later, and you were weighing up the next approach without quite recalling how you got from there to here.

Somehow, it must be possible to convey that in fiction. If anyone knows, I'll be delighted if they let me know. I'm still fumbling around trying to discover by a process of elimination.

I think the yomping part highlights the fact that fiction has its limits. If you gave a proportional account of the time spent and the actual action took, say, four pages, believe me, you will lose all your readers with, say, twenty pages accurately describing walking ankle-deep through a bog.

I think the yomping part highlights the fact that fiction has its limits. If you gave a proportional account of the time spent and the actual action took, say, four pages, believe me, you will lose all your readers with, say, twenty pages accurately describing walking ankle-deep through a bog.I do not have David's experience, but I have written some battle scenes, and my view is like the following. As an example, a space battle, where (because it was the commander's POV) I tried to accurately describe what the "field" looked like to get started, there was the first manoeuvre where it was found the field was somewhat different than believed because the opposition had done something unexpected, an unexpected counter plan, about two paras describing how he felt as his ships closed the distance to where it now appeared they were and how he could approach from behind, his realization of how he had accidentally thwarted treachery, and how he hoped the opposition would not see him. Those two paras explained this was the longest time part - but it was all the same so don't bore. Then the action, in which from the POV of any character was very rapid, with two sentences devoted, then an overall "bigger picture" to describe what was going on to all of them. Not ideal, but it was the best I could do. That was round 1. Then it continued.

My number one rule is 'focus on what is important.'

My number one rule is 'focus on what is important.'I always shortcut travel - because, unless the story is really about wandering around in the bush - wandering around in the bush is boring. (Or, you have some interesting anecdotes and banter to relieve the tedium of walking, in which case the anecdotes/banter becomes the story...)

Here's this 30s clip from 'Indiana Jones and the Lost Ark.'

REF: Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5TY5F...

David wrote: "If I knew how to convincingly convey time dilation in a story, I'd be a better writer (and possibly a richer one) than I am.

David wrote: "If I knew how to convincingly convey time dilation in a story, I'd be a better writer (and possibly a richer one) than I am.It's one of those situation where I can see what the problem is, but ha..."

If I was in your shoes, this is what I would do.

[1] Time dragged in real life - 5% of the page space in your story.

[2] Where time rushed - 95% of the page space in your story.

David raises important issues/concerns/challenges. I agree with the replies. Of course, if one has combat experience, that is great to draw on. I do not. The closest I can claim is the adrenaline rush from hunting--not even close to combat but closer than target shooting at the range, which is closer than sitting in a chair and watching Schwarzenegger movies.

David raises important issues/concerns/challenges. I agree with the replies. Of course, if one has combat experience, that is great to draw on. I do not. The closest I can claim is the adrenaline rush from hunting--not even close to combat but closer than target shooting at the range, which is closer than sitting in a chair and watching Schwarzenegger movies.Yes, I've experienced the slowing of time and the tunnel vision--not only sight but all senses--that occurs when you are about to pull the trigger on a living creature. However, as my life was never hanging in jeopardy, hunting is nothing like combat, I'd imagine. Still, it gives a reference point to anchor to when writing these scenes. I'll describe how the senses become focused on the target immediately in sight, and so on. To allow the plot to flow at a fast pace, the description and dialog (if any) has to move quickly.

David wrote: "By contrast, when I'm writing from a higher POV, I tend to not try and include the nitty-gritty details of what's happening on the ground. If the story is about the big picture, then I concentrate on the big picture. ..."

David wrote: "By contrast, when I'm writing from a higher POV, I tend to not try and include the nitty-gritty details of what's happening on the ground. If the story is about the big picture, then I concentrate on the big picture. ..."Hi David,

What do you mean by 'higher POV,' do you have an example or some more explanation of what this is?

I was thinking in terms of the Generals and politicians and so forth who make the higher-level decisions, such as whether D-Day is aimed at Normandy or Pas-de-Calais, and how the grand scheme of things unveils.

I was thinking in terms of the Generals and politicians and so forth who make the higher-level decisions, such as whether D-Day is aimed at Normandy or Pas-de-Calais, and how the grand scheme of things unveils. The lower POV tend not to have a clue why they're here rather than there (and quite often weren't necessarily entirely sure where here might be), but they do have a fairly clear idea of the nitty-gritty.

For individual adventures, they tend to have both, although how much of the high level they get is a matter for the individual writer.

Hi David,

Hi David,I get what you're talking about.

For me that really comes down to who has the most initiative in a given scenario. I.e. who is best placed to shape events (and hence the narrative) going forward.

I haven't done big set battles. It's mostly equivalent to small teams of 4 to 8 combatants against each other, or spy vs spy vs spy assassinations...

(I didn't make a mistake with 3 spys - I have multiple factions in conflict with each other)

I have tried the higher level combat. I would amend one of David's sentences : they have hopes for "how the grand scheme of things unveils." In reality, and in a story as well, the General cannot know what the opposition's response will be, and it is important in a story that the opposition is not merely some sort of backdrop, except in the specific case of, on a smaller scale, a well thought-out surprise ambush. If the opposition is merely a backdrop for the protagonist's "cleverness" it won't be much of a story.

I have tried the higher level combat. I would amend one of David's sentences : they have hopes for "how the grand scheme of things unveils." In reality, and in a story as well, the General cannot know what the opposition's response will be, and it is important in a story that the opposition is not merely some sort of backdrop, except in the specific case of, on a smaller scale, a well thought-out surprise ambush. If the opposition is merely a backdrop for the protagonist's "cleverness" it won't be much of a story.Even with the well-thought-out ambush, there is scope for being different. I had one (in Roman times) where the opposition had no chance, but the Roman commander offered the surrender option with the end-position the opposition became a client-ally. The Roman leaders sometimes did this, so it was not out of place, and it led to better future story options.

Graeme wrote: "For me that really comes down to who has the most initiative in a given scenario. I.e. who is best placed to shape events (and hence the narrative) goin..."

Graeme wrote: "For me that really comes down to who has the most initiative in a given scenario. I.e. who is best placed to shape events (and hence the narrative) goin..."I think that's the key point. What the needs of the narrative are. If the story is set (to take one specific example) around the Falklands Conflict, and focuses on, say, the decision whether or not the British forces should/should not have sunk the Belgrano, the view of some Royal Marine trudging westwards becomes supremely irrelevant to the story. If, on the other hand, the story is a romance (don't laugh - it's how I met my wife. She was a nurse Down South, I get wounded, and the rest became history. Mills & Boon rejected the plot as being too unrealistic), then the trudging details are pretty minor. If one is writing an account along the lines of Quartered Safe Out Here, by MacDonald Fraser, then the trudging becomes rather central.

It's the needs of the narrative.

I love the idea that editors reject a story as unrealistic when it is based on something that was true. I had one of mine (colonization of Mars) rejected because I had some guys running a stock market fraud and that was considered to be "unrealistic".

I love the idea that editors reject a story as unrealistic when it is based on something that was true. I had one of mine (colonization of Mars) rejected because I had some guys running a stock market fraud and that was considered to be "unrealistic".

Geez, Ian - Stock Market Fraud - that's amazing.

Geez, Ian - Stock Market Fraud - that's amazing.Clearly, you're way out on the fringe with that one...

/sarc.

That's me, Graeme, way out there in left field, all by myself. Nobody could conceivably do that, could they?

That's me, Graeme, way out there in left field, all by myself. Nobody could conceivably do that, could they?

Only a 'conspiracy theorist,' could imagine that a fine and upstanding institution like the stock market could ever be compromised...

Only a 'conspiracy theorist,' could imagine that a fine and upstanding institution like the stock market could ever be compromised...

It's almost as if some people involved in the stock market are more interested in money than in morality.

It's almost as if some people involved in the stock market are more interested in money than in morality.The weird things authors will dream up.

Books mentioned in this topic

The Writer's Guide to Weapons: A Practical Reference for Using Firearms and Knives in Fiction (other topics)A Guide to First Contact (other topics)

The Tau Device (other topics)

Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser (other topics)

Brant (other topics)

Authors mentioned in this topic

James White (other topics)J.R.R. Tolkien (other topics)

Robert E. Howard (other topics)

How to make sure that your combat scenes make physical sense, even in worlds where characters can have magic powers or supernatural abilities - if your combat doesn't make sense, you will blow the reader's suspension of disbelief and they will start to lose interest.

Thoughts?