The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Nicholas Nickleby

>

NN, Chp. 61-65

Chapter 63 sets a counterpoint to its very dark predecessor and since I am a very grumpy person – and quite sorry for losing Ralph so early 😉 – I will deal with it very briefly: The Cheeryble brothers finally set the love matters right, showing Nicholas that they would not have Frank “’marry for money, when youth, beauty, and every amiable virtue and excellence were to be had for love’”. This is probably the first time that somebody in our novel says this in so many words, whereas up to now all the marriage projects and much of the family relations we read about had been considered with money or other personal profit derived from such connections – with the possible exception of the marriage of John Browdie and ‘Tilda Price. In the wake of the two marriage announcements that are now due, Tim Linkinwater also decides to make a clean breast of his feelings to Miss La Creevy, and his marriage proposal is one of the nicest speeches of the whole novel. So nice, in fact, that I am going to insert it here:

When Miss La Creevy says yes to such a proposal, it must be owned that she forfeits the good opinion of the excellent Mrs. Nickleby, who now considers her as something like a schemer, but that is probably a price easily paid. To make the merry round complete, Newman Noggs makes his appearance, in better garments than usual (thanks to the Cheerybles) and telling Nick that he now is another man.

What more is there to tell? Chapter 64 sees Nicholas on a journey into Yorkshire again because whenever he has tried to write his friends the Browdies a letter to tell them about the changes in his life, he found that the letter sounded too formal. When Kate and Nicholas go to the coach station, they once more witness Mr. Mantalini, this time attached to a plump woman, on whom he most evidently scrounges – although on a smaller level than in his olden days – but who seems to have already found out about him because she scolds him and makes him turn a mangle. Why do you think we get this glimpse into a minor character’s situation? What might the mangle stand for, and where on earth is Madam Mantalini?

The narrator then hurries us to Yorkshire in order to show us the ending of Dotheboys Hall: News of Mr. Squeers being transported to Australia (?) has finally reached the school, and the boys there want to wreak vengeance on their remaining oppressors. It is only John Browdie’s timely arrival that saves Mrs. Squeers and her children from being gruesomely manhandled by the boys. However, Fanny Squeers does not evince a lot of gratefulness to her saviour, reproaching him with having incited the boys to run away – which he, indeed, did but merely to hinder them from venting their anger on the Squeerses. Notwithstanding these reproaches John’s reaction to Fanny is conciliatory, and he even tells her that he and ‘Tilda will help her if she ever wants to get away from that place. The Browdies will surely help the children get away from the place, supplying them, clandestinely, with small amounts of money and victuals.

Are you satisfied with this ending of Dotheboys Hall? Or would you have wished Mrs. Squeers to have experienced a more memorable punishment? What might happen to the children, Master Wackford included? Do you think that Fanny will eventually escape the influence of Dotheboys Hall?

There is one little detail I did not mention but leave it to Peter, who is a specialist in (view spoiler) Can you guess which detail I mean?

In the final chapter, our narrator does something I extremely love in a novel: The narrator gives a brief account of what further happens to the major and minor characters. It is quite an old-fashioned literary device, but I enjoy it for whatever reason. Do you think that everyone got what they deserved, or are there any complaints?

I was quite struck with the first sentence where it says that Madeline “gave her hand and her fortune to Nicholas”. What feelings did you have when you read this? And most importantly, what effect did the last paragraphs of the novel have on you?

I hope you enjoyed reading NN as much as I did, and I am looking forward to the Christmas read with you! Thanks for always being so active in our discussions – this is what keeps our wonderful reading group alive!

”’Come,’ said Tim, ‘let’s be a comfortable couple. We shall live in the old house here, where I have been for four-and-forty year; we shall go to the old church, where I’ve been every Sunday morning all through that time; we shall have all my old friends about us—Dick, the arch-way, the pump, the flower-pots, and Mr. Frank’s children, and Mr. Nickleby’s children, that we shall seem like grandfather and grandmother to. Let’s be a comfortable couple, and take care of each other, and if we should get deaf, or lame, or blind, or bed-ridden, how glad we shall be that we have somebody we are fond of always to talk to and sit with! Let’s be a comfortable couple. Now do, my dear.’”

When Miss La Creevy says yes to such a proposal, it must be owned that she forfeits the good opinion of the excellent Mrs. Nickleby, who now considers her as something like a schemer, but that is probably a price easily paid. To make the merry round complete, Newman Noggs makes his appearance, in better garments than usual (thanks to the Cheerybles) and telling Nick that he now is another man.

What more is there to tell? Chapter 64 sees Nicholas on a journey into Yorkshire again because whenever he has tried to write his friends the Browdies a letter to tell them about the changes in his life, he found that the letter sounded too formal. When Kate and Nicholas go to the coach station, they once more witness Mr. Mantalini, this time attached to a plump woman, on whom he most evidently scrounges – although on a smaller level than in his olden days – but who seems to have already found out about him because she scolds him and makes him turn a mangle. Why do you think we get this glimpse into a minor character’s situation? What might the mangle stand for, and where on earth is Madam Mantalini?

The narrator then hurries us to Yorkshire in order to show us the ending of Dotheboys Hall: News of Mr. Squeers being transported to Australia (?) has finally reached the school, and the boys there want to wreak vengeance on their remaining oppressors. It is only John Browdie’s timely arrival that saves Mrs. Squeers and her children from being gruesomely manhandled by the boys. However, Fanny Squeers does not evince a lot of gratefulness to her saviour, reproaching him with having incited the boys to run away – which he, indeed, did but merely to hinder them from venting their anger on the Squeerses. Notwithstanding these reproaches John’s reaction to Fanny is conciliatory, and he even tells her that he and ‘Tilda will help her if she ever wants to get away from that place. The Browdies will surely help the children get away from the place, supplying them, clandestinely, with small amounts of money and victuals.

Are you satisfied with this ending of Dotheboys Hall? Or would you have wished Mrs. Squeers to have experienced a more memorable punishment? What might happen to the children, Master Wackford included? Do you think that Fanny will eventually escape the influence of Dotheboys Hall?

There is one little detail I did not mention but leave it to Peter, who is a specialist in (view spoiler) Can you guess which detail I mean?

In the final chapter, our narrator does something I extremely love in a novel: The narrator gives a brief account of what further happens to the major and minor characters. It is quite an old-fashioned literary device, but I enjoy it for whatever reason. Do you think that everyone got what they deserved, or are there any complaints?

I was quite struck with the first sentence where it says that Madeline “gave her hand and her fortune to Nicholas”. What feelings did you have when you read this? And most importantly, what effect did the last paragraphs of the novel have on you?

I hope you enjoyed reading NN as much as I did, and I am looking forward to the Christmas read with you! Thanks for always being so active in our discussions – this is what keeps our wonderful reading group alive!

Chapter 61

Chapter 61I'm giving this chapter the subtitle Let's All Worship Nicholas Chapter.

Nicholas and Kate come to the conclusion that neither she nor he will actively pursue the fulfillment of their love stories because both Madeline and Frank are wealthy ...

As Kate's mom has already told Kate what Nicholas expects regarding Kate and Frank, I'm thinking Kate is only doing what Nicholas expects her to do and not what she would necessarily do -- one reason why I have given this chapter the subtitle I have.

I almost overdosed on the Nicholas syrup in this chapter.

PS: Sometimes, when Nicholas talks to Kate, I'm hearing him "talking down to her" in the middle of all the love and regard for one another.

Despite the klutzy ending to OT, I'm finding it the far more layered, substantive novel of the two. You could dig into subjects like class and gender in OT, as well as why Nancy does what she does, reacts the way she does.

Despite the klutzy ending to OT, I'm finding it the far more layered, substantive novel of the two. You could dig into subjects like class and gender in OT, as well as why Nancy does what she does, reacts the way she does. I'm sorry to say, I'm not finding NN to be much of anything. It seems to be about a young boy who, because he acts aristocratic when he is really poor, is the recipient of all kinds of lucky breaks, and is too full of himself to see that he isn't the cause of his own success.

The one question left unanswered is, who is Nicholas's fairy godmother? Because he surely has one.

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

The moment of bidding Nicholas farewell has arrived, and my parting reflections are influenced by wonderment at how different a novel, a good one, works on the reader (probably a..."

Tristram

Oh, my. Mrs Nickleby is surely the most annoying character in Dickens’s first three novels. We should keep a running tally on such catagories as most annoying character, most noble character, funniest character, most enduring character etc. etc.

The question of marrying “up” or “down” in society is a pressing point for Victorians. As we read the novel from the 21C I think it is very difficult for us to grasp how important the class system was, and how people took an almost rabid interest in its overall function. When one considers that on a woman’s marriage to a man, all her wealth and property became her husband’s, the position of Nicholas and Madeline would be one of importance for both parties.

Thankfully, the ending of NN gives us happy couples who marry, and thus, by definition, we have a comedy. We know that Madeline and Nicholas will always be faithful and true to one another and we celebrate the Linkinwater - La Cleery union. As well, Kate marries Frank and all is well with the Cheeryble’s.

The moment of bidding Nicholas farewell has arrived, and my parting reflections are influenced by wonderment at how different a novel, a good one, works on the reader (probably a..."

Tristram

Oh, my. Mrs Nickleby is surely the most annoying character in Dickens’s first three novels. We should keep a running tally on such catagories as most annoying character, most noble character, funniest character, most enduring character etc. etc.

The question of marrying “up” or “down” in society is a pressing point for Victorians. As we read the novel from the 21C I think it is very difficult for us to grasp how important the class system was, and how people took an almost rabid interest in its overall function. When one considers that on a woman’s marriage to a man, all her wealth and property became her husband’s, the position of Nicholas and Madeline would be one of importance for both parties.

Thankfully, the ending of NN gives us happy couples who marry, and thus, by definition, we have a comedy. We know that Madeline and Nicholas will always be faithful and true to one another and we celebrate the Linkinwater - La Cleery union. As well, Kate marries Frank and all is well with the Cheeryble’s.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Despite the klutzy ending to OT, I'm finding it the far more layered, substantive novel of the two. You could dig into subjects like class and gender in OT, as well as why Nancy does what she does,..."

Grump.

Grump.

Clasping the iron railings with his hands, looked eagerly in, wondering which might be his grave

Chapter 62

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

He had to pass a poor, mean burial-ground—a dismal place, raised a few feet above the level of the street, and parted from it by a low parapet-wall and an iron railing; a rank, unwholesome, rotten spot, where the very grass and weeds seemed, in their frouzy growth, to tell that they had sprung from paupers’ bodies, and had struck their roots in the graves of men, sodden, while alive, in steaming courts and drunken hungry dens. And here, in truth, they lay, parted from the living by a little earth and a board or two—lay thick and close—corrupting in body as they had in mind—a dense and squalid crowd. Here they lay, cheek by jowl with life: no deeper down than the feet of the throng that passed there every day, and piled high as their throats. Here they lay, a grisly family, all these dear departed brothers and sisters of the ruddy clergyman who did his task so speedily when they were hidden in the ground!

As he passed here, Ralph called to mind that he had been one of a jury, long before, on the body of a man who had cut his throat; and that he was buried in this place. He could not tell how he came to recollect it now, when he had so often passed and never thought about him, or how it was that he felt an interest in the circumstance; but he did both; and stopping, and clasping the iron railings with his hands, looked eagerly in, wondering which might be his grave.

While he was thus engaged, there came towards him, with noise of shouts and singing, some fellows full of drink, followed by others, who were remonstrating with them and urging them to go home in quiet. They were in high good-humour; and one of them, a little, weazen, hump-backed man, began to dance. He was a grotesque, fantastic figure, and the few bystanders laughed. Ralph himself was moved to mirth, and echoed the laugh of one who stood near and who looked round in his face. When they had passed on, and he was left alone again, he resumed his speculation with a new kind of interest; for he recollected that the last person who had seen the suicide alive, had left him very merry, and he remembered how strange he and the other jurors had thought that at the time.

He could not fix upon the spot among such a heap of graves, but he conjured up a strong and vivid idea of the man himself, and how he looked, and what had led him to do it; all of which he recalled with ease. By dint of dwelling upon this theme, he carried the impression with him when he went away; as he remembered, when a child, to have had frequently before him the figure of some goblin he had once seen chalked upon a door. But as he drew nearer and nearer home he forgot it again, and began to think how very dull and solitary the house would be inside.

Ralph makes one last appointment - and keeps it

Chapter 62

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated;

He spoke no more; but, after a pause, softly groped his way out of the room, and up the echoing stairs—up to the top—to the front garret—where he closed the door behind him, and remained.

It was a mere lumber-room now, but it yet contained an old dismantled bedstead; the one on which his son had slept; for no other had ever been there. He avoided it hastily, and sat down as far from it as he could.

The weakened glare of the lights in the street below, shining through the window which had no blind or curtain to intercept it, was enough to show the character of the room, though not sufficient fully to reveal the various articles of lumber, old corded trunks and broken furniture, which were scattered about. It had a shelving roof; high in one part, and at another descending almost to the floor. It was towards the highest part that Ralph directed his eyes; and upon it he kept them fixed steadily for some minutes, when he rose, and dragging thither an old chest upon which he had been seated, mounted on it, and felt along the wall above his head with both hands. At length, they touched a large iron hook, firmly driven into one of the beams.

At that moment, he was interrupted by a loud knocking at the door below. After a little hesitation he opened the window, and demanded who it was.

‘I want Mr. Nickleby,’ replied a voice.

‘What with him?’

‘That’s not Mr. Nickleby’s voice, surely?’ was the rejoinder.

It was not like it; but it was Ralph who spoke, and so he said.

The voice made answer that the twin brothers wished to know whether the man whom he had seen that night was to be detained; and that although it was now midnight they had sent, in their anxiety to do right.

‘Yes,’ cried Ralph, ‘detain him till tomorrow; then let them bring him here—him and my nephew—and come themselves, and be sure that I will be ready to receive them.’

‘At what hour?’ asked the voice.

‘At any hour,’ replied Ralph fiercely. ‘In the afternoon, tell them. At any hour, at any minute. All times will be alike to me.’

Tristram wrote: "Dear Curiosities,

The moment of bidding Nicholas farewell has arrived, and my parting reflections are influenced by wonderment at how different a novel, a good one, works on the reader (probably a..."

In regards to how I recall NN I thought Nicholas’s time with the Crummles was much larger than it turned out to be. Funny how one’s mind recalls details. I can also not recall loathing Ralph Nickleby as much as I did this time.

As for my favourite character, this time around it was Newman Noggs. Newman Noggs and in OT it was Nancy. Am I stuck on the letter “N”?

The moment of bidding Nicholas farewell has arrived, and my parting reflections are influenced by wonderment at how different a novel, a good one, works on the reader (probably a..."

In regards to how I recall NN I thought Nicholas’s time with the Crummles was much larger than it turned out to be. Funny how one’s mind recalls details. I can also not recall loathing Ralph Nickleby as much as I did this time.

As for my favourite character, this time around it was Newman Noggs. Newman Noggs and in OT it was Nancy. Am I stuck on the letter “N”?

Oh, Mr, Linkinwater, You're Joking!" "No, No, I'm Not. I'm not Indeed," Said Tim

Chapter 63

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Tim sat down beside Miss La Creevy, and, crossing one leg over the other so that his foot—he had very comely feet and happened to be wearing the neatest shoes and black silk stockings possible—should come easily within the range of her eye, said in a soothing way:

‘Don’t cry!’

‘I must,’ rejoined Miss La Creevy.

‘No, don’t,’ said Tim. ‘Please don’t; pray don’t.’

‘I am so happy!’ sobbed the little woman.

‘Then laugh,’ said Tim. ‘Do laugh.’

What in the world Tim was doing with his arm, it is impossible to conjecture, but he knocked his elbow against that part of the window which was quite on the other side of Miss La Creevy; and it is clear that it could have no business there.

‘Do laugh,’ said Tim, ‘or I’ll cry.’

‘Why should you cry?’ asked Miss La Creevy, smiling.

‘Because I’m happy too,’ said Tim. ‘We are both happy, and I should like to do as you do.’

Surely, there never was a man who fidgeted as Tim must have done then; for he knocked the window again—almost in the same place—and Miss La Creevy said she was sure he’d break it.

‘I knew,’ said Tim, ‘that you would be pleased with this scene.’

‘It was very thoughtful and kind to remember me,’ returned Miss La Creevy. ‘Nothing could have delighted me half so much.’

Why on earth should Miss La Creevy and Tim Linkinwater have said all this in a whisper? It was no secret. And why should Tim Linkinwater have looked so hard at Miss La Creevy, and why should Miss La Creevy have looked so hard at the ground?

‘It’s a pleasant thing,’ said Tim, ‘to people like us, who have passed all our lives in the world alone, to see young folks that we are fond of, brought together with so many years of happiness before them.’

‘Ah!’ cried the little woman with all her heart, ‘that it is!’

‘Although,’ pursued Tim ‘although it makes one feel quite solitary and cast away. Now don’t it?’

Miss La Creevy said she didn’t know. And why should she say she didn’t know? Because she must have known whether it did or not.

‘It’s almost enough to make us get married after all, isn’t it?’ said Tim.

‘Oh, nonsense!’ replied Miss La Creevy, laughing. ‘We are too old.’

‘Not a bit,’ said Tim; ‘we are too old to be single. Why shouldn’t we both be married, instead of sitting through the long winter evenings by our solitary firesides? Why shouldn’t we make one fireside of it, and marry each other?’

‘Oh, Mr. Linkinwater, you’re joking!’

‘No, no, I’m not. I’m not indeed,’ said Tim. ‘I will, if you will. Do, my dear!’

‘It would make people laugh so.’

‘Let ‘em laugh,’ cried Tim stoutly; ‘we have good tempers I know, and we’ll laugh too. Why, what hearty laughs we have had since we’ve known each other!’

‘So we have,’ cried Miss La Creevy—giving way a little, as Tim thought.

I'm very much the grump when it comes to NN. I actually wanted John Brodie to punch Nicholas in the nose way back when they were playing the game in the parlor. Instead he gives him money.

I'm very much the grump when it comes to NN. I actually wanted John Brodie to punch Nicholas in the nose way back when they were playing the game in the parlor. Instead he gives him money.

Reduced circumstances of Mr. Mantalini

Chapter 64

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The place they had just been in called up so many recollections, and Kate had so many anecdotes of Madeline, and Nicholas so many anecdotes of Frank, and each was so interested in what the other said, and both were so happy and confiding, and had so much to talk about, that it was not until they had plunged for a full half-hour into that labyrinth of streets which lies between Seven Dials and Soho, without emerging into any large thoroughfare, that Nicholas began to think it just possible they might have lost their way.

The possibility was soon converted into a certainty; for, on looking about, and walking first to one end of the street and then to the other, he could find no landmark he could recognise, and was fain to turn back again in quest of some place at which he could seek a direction.

It was a by-street, and there was nobody about, or in the few wretched shops they passed. Making towards a faint gleam of light which streamed across the pavement from a cellar, Nicholas was about to descend two or three steps so as to render himself visible to those below and make his inquiry, when he was arrested by a loud noise of scolding in a woman’s voice.

‘Oh come away!’ said Kate, ‘they are quarrelling. You’ll be hurt.’

‘Wait one instant, Kate. Let us hear if there’s anything the matter,’ returned her brother. ‘Hush!’

‘You nasty, idle, vicious, good-for-nothing brute,’ cried the woman, stamping on the ground, ‘why don’t you turn the mangle?’

‘So I am, my life and soul!’ replied the man’s voice. ‘I am always turning. I am perpetually turning, like a demd old horse in a demnition mill. My life is one demd horrid grind!’

‘Then why don’t you go and list for a soldier?’ retorted the woman; ‘you’re welcome to.’

‘For a soldier!’ cried the man. ‘For a soldier! Would his joy and gladness see him in a coarse red coat with a little tail? Would she hear of his being slapped and beat by drummers demnebly? Would she have him fire off real guns, and have his hair cut, and his whiskers shaved, and his eyes turned right and left, and his trousers pipeclayed?’

‘Dear Nicholas,’ whispered Kate, ‘you don’t know who that is. It’s Mr Mantalini I am confident.’

‘Do make sure! Peep at him while I ask the way,’ said Nicholas. ‘Come down a step or two. Come!’

Drawing her after him, Nicholas crept down the steps and looked into a small boarded cellar. There, amidst clothes-baskets and clothes, stripped up to his shirt-sleeves, but wearing still an old patched pair of pantaloons of superlative make, a once brilliant waistcoat, and moustache and whiskers as of yore, but lacking their lustrous dye—there, endeavouring to mollify the wrath of a buxom female—not the lawful Madame Mantalini, but the proprietress of the concern—and grinding meanwhile as if for very life at the mangle, whose creaking noise, mingled with her shrill tones, appeared almost to deafen him—there was the graceful, elegant, fascinating, and once dashing Mantalini.

The breaking up of Dotheboys Hall

Chapter 64

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The news of Mr. Squeers’s downfall had reached Dotheboys; that was quite clear. To all appearance, it had very recently become known to the young gentlemen; for the rebellion had just broken out.

It was one of the brimstone-and-treacle mornings, and Mrs. Squeers had entered school according to custom with the large bowl and spoon, followed by Miss Squeers and the amiable Wackford: who, during his father’s absence, had taken upon him such minor branches of the executive as kicking the pupils with his nailed boots, pulling the hair of some of the smaller boys, pinching the others in aggravating places, and rendering himself, in various similar ways, a great comfort and happiness to his mother. Their entrance, whether by premeditation or a simultaneous impulse, was the signal of revolt. While one detachment rushed to the door and locked it, and another mounted on the desks and forms, the stoutest (and consequently the newest) boy seized the cane, and confronting Mrs Squeers with a stern countenance, snatched off her cap and beaver bonnet, put them on his own head, armed himself with the wooden spoon, and bade her, on pain of death, go down upon her knees and take a dose directly. Before that estimable lady could recover herself, or offer the slightest retaliation, she was forced into a kneeling posture by a crowd of shouting tormentors, and compelled to swallow a spoonful of the odious mixture, rendered more than usually savoury by the immersion in the bowl of Master Wackford’s head, whose ducking was intrusted to another rebel. The success of this first achievement prompted the malicious crowd, whose faces were clustered together in every variety of lank and half-starved ugliness, to further acts of outrage. The leader was insisting upon Mrs. Squeers repeating her dose, Master Squeers was undergoing another dip in the treacle, and a violent assault had been commenced on Miss Squeers, when John Browdie, bursting open the door with a vigorous kick, rushed to the rescue. The shouts, screams, groans, hoots, and clapping of hands, suddenly ceased, and a dead silence ensued.

The breaking up of Dotheboys Hall

The breaking up of Dotheboys HallReminds me of a scene in the stage musical Les Miserables (at least as seen on TV).

The children at their cousin's grave

Chapter 65

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The first act of Nicholas, when he became a rich and prosperous merchant, was to buy his father’s old house. As time crept on, and there came gradually about him a group of lovely children, it was altered and enlarged; but none of the old rooms were ever pulled down, no old tree was ever rooted up, nothing with which there was any association of bygone times was ever removed or changed.

Within a stone’s throw was another retreat, enlivened by children’s pleasant voices too; and here was Kate, with many new cares and occupations, and many new faces courting her sweet smile (and one so like her own, that to her mother she seemed a child again), the same true gentle creature, the same fond sister, the same in the love of all about her, as in her girlish days.

Mrs. Nickleby lived, sometimes with her daughter, and sometimes with her son, accompanying one or other of them to London at those periods when the cares of business obliged both families to reside there, and always preserving a great appearance of dignity, and relating her experiences (especially on points connected with the management and bringing-up of children) with much solemnity and importance. It was a very long time before she could be induced to receive Mrs. Linkinwater into favour, and it is even doubtful whether she ever thoroughly forgave her.

There was one grey-haired, quiet, harmless gentleman, who, winter and summer, lived in a little cottage hard by Nicholas’s house, and, when he was not there, assumed the superintendence of affairs. His chief pleasure and delight was in the children, with whom he was a child himself, and master of the revels. The little people could do nothing without dear Newman Noggs.

The grass was green above the dead boy’s grave, and trodden by feet so small and light, that not a daisy drooped its head beneath their pressure. Through all the spring and summertime, garlands of fresh flowers, wreathed by infant hands, rested on the stone; and, when the children came to change them lest they should wither and be pleasant to him no longer, their eyes filled with tears, and they spoke low and softly of their poor dead cousin.

Commentary:

Browne is in general less successful with the sentimental plot — the encounters of Nicholas with Madeline, the troubles of Kate, and the fate of Smike. At their worst, such plates are incompetent, as in the portrayal of Madeline in "Nicholas recognizes the Young Lady unknown" (ch. 40) (That Browne was aware that he was having trouble with the pose of Madeline is indicated by the several marginal sketches of her figure in the working drawing. The drawing is in DH, and is reproduced in Michael Slater, ed., The Catalogue of the Suzannet Charles Dickens Collection (London and New York: Sotheby Parke Bernet Publications, 1975), or are centered on awkward, melodramatic poses, as in "Nicholas congratulates Arthur Gride on his Wedding Morning" (ch. 54). At their best, they help to sum up the novel's moral themes, as in the designs related to Smike in which the action unfolds in a wooded setting: "The recognition" (ch. 58), and "The children at their cousin's grave" (ch. 65). The latter plate is the last etching in the book and the first appearance of a church since the wrapper, where Ralph Nickleby was seen to be lost to Christianity in a swamp of materialism. Here, the characters are in harmony with Nature, the Church, and with the Christian view of suffering and death as embodied in the story of Smike. It is nothing like what Browne accomplishes by use of frontispieces for summing up the central meanings of a novel (and in this one, a portrait of the author by Maclise is the frontispiece). although the sentimental style returns from time to time, it remains a far less important aspect of Browne's development away from the caricature than is what we might call the "sequential" mode. The two novels in Master Humphrey's Clock, which follow almost immediately upon Nicholas Nickleby, are special among Browne's assignments for Dickens, and yet they may be seen as preparations for the next novel in monthly parts, Martin Chuzzlewit, in which Browne's debt to and development of the Hogarthian tradition, the "progress" in all its complex manifestations, first really crystallize.

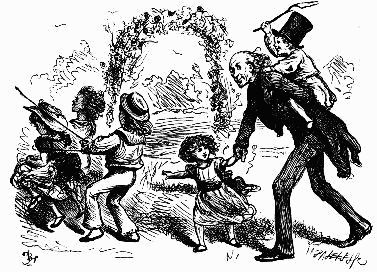

The Little People Could Do Nothing Without Dear Newman Noggs

Chapter 65

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

There was one grey-haired, quiet, harmless gentleman, who, winter and summer, lived in a little cottage hard by Nicholas’s house, and, when he was not there, assumed the superintendence of affairs. His chief pleasure and delight was in the children, with whom he was a child himself, and master of the revels. The little people could do nothing without dear Newman Noggs.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "I'm very much the grump when it comes to NN. I actually wanted John Brodie to punch Nicholas in the nose way back when they were playing the game in the parlor. Instead he gives him money."

See message 6. You might as well see it too Tristram.

See message 6. You might as well see it too Tristram.

Kim wrote: "The Little People Could Do Nothing Without Dear Newman Noggs

Chapter 65

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

There was one grey-haired, quiet, harmless gentleman, who, winter and summer, lived in a l..."

Thanks Kim

I am bravely ignoring the criticism of Phiz in the commentary.

The Chapter 65 illustration of Fred Barnard was very interesting. It shows Newman Noggs at play with the children, and we know from the text that Noggs became a special favourite of the children. What I found most interesting is that Barnard has Noggs looking at his viewers. Very rarely do we see such an intimacy between an illustrated character and the reader. Noggs is presented as being dressed better, and with one child holding his hand and one joyfully ridding on Noggs’s back, we can only smile and realize that he has found peace at last.

Chapter 65

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

There was one grey-haired, quiet, harmless gentleman, who, winter and summer, lived in a l..."

Thanks Kim

I am bravely ignoring the criticism of Phiz in the commentary.

The Chapter 65 illustration of Fred Barnard was very interesting. It shows Newman Noggs at play with the children, and we know from the text that Noggs became a special favourite of the children. What I found most interesting is that Barnard has Noggs looking at his viewers. Very rarely do we see such an intimacy between an illustrated character and the reader. Noggs is presented as being dressed better, and with one child holding his hand and one joyfully ridding on Noggs’s back, we can only smile and realize that he has found peace at last.

Tristram

Thanks for the spoiler “shoutout” to me in Chapter 63. I was, of course, relieved to read that Dick the blackbird was promoted in semi-retirement “to a warm corner in the common sitting-room.” That Dick would have such a pride of place in his cage above miniatures of Tim and Mrs Linkinwater seems like a perfect place for all three to share their coming years together.

At the end of Chapter 64 we read that when Dotheboys Hall was dissolved the former students scattered about the countryside; one “had a dead bird in a little cage; [a little boy] had wandered nearly twenty miles and when his poor favourite died, lost courage, and lay down beside him.”

We also recall in Phiz’s illustration of Madeline’s room with her father that above the harp was a bird cage. For that illustration the bird cage was an emblem of entrapment. Madeline, like the harp in the illustration, was silenced by her circumstances. She was, like a bird, trapped in a cage. Her cage was one of parental domination, abuse, poverty, and societal pressures. For the boy who loses his courage after his escape from Dotheboys Hall, the bird is suggestive of the fact that its owner has been rendered unfit for his freedom in society. Like his bird in a cage, he will never be free. The only freedom possible is that found through death.

Thanks for the spoiler “shoutout” to me in Chapter 63. I was, of course, relieved to read that Dick the blackbird was promoted in semi-retirement “to a warm corner in the common sitting-room.” That Dick would have such a pride of place in his cage above miniatures of Tim and Mrs Linkinwater seems like a perfect place for all three to share their coming years together.

At the end of Chapter 64 we read that when Dotheboys Hall was dissolved the former students scattered about the countryside; one “had a dead bird in a little cage; [a little boy] had wandered nearly twenty miles and when his poor favourite died, lost courage, and lay down beside him.”

We also recall in Phiz’s illustration of Madeline’s room with her father that above the harp was a bird cage. For that illustration the bird cage was an emblem of entrapment. Madeline, like the harp in the illustration, was silenced by her circumstances. She was, like a bird, trapped in a cage. Her cage was one of parental domination, abuse, poverty, and societal pressures. For the boy who loses his courage after his escape from Dotheboys Hall, the bird is suggestive of the fact that its owner has been rendered unfit for his freedom in society. Like his bird in a cage, he will never be free. The only freedom possible is that found through death.

In the last segment, there was some discussion about the lack of foreshadowing when it came to Smike's paternity. I'm responding in this thread now that we know what became of Ralph.

In the last segment, there was some discussion about the lack of foreshadowing when it came to Smike's paternity. I'm responding in this thread now that we know what became of Ralph. For me, the lack of foreshadowing is evidence of Dickens still needing some time to mature as an author. The closest thing I can think of is the mention - three times that I can remember - of the beams in the attic. Smike mentioned them twice as one of his only pre-Dotheboys memories, and then they're mentioned again when Ralph hangs himself. But let's face it - if it was meant to be foreshadowing, Dickens did a lousy job of it. I don't think that attic or its beams were ever alluded to on Ralph's side of things prior to the revelation. If, perhaps, he'd met with Squeers in the attic to discuss something without Noggs being close at hand, and the beams were described as part of the scenery, for example, that might have given observant readers a little something to go on.

I do believe Dickens had Smike's paternity planned out all along - the coincidences in OT prove to us that he likes these connections. But I think he's still just not sure how to feed the readers gradually, instead of stuffing us with a Pickwickian-sized banquet of coincidences all at once in the final chapters.

Makes me wonder if CD was the type to write "The End" and then leave the finished stories in the past, or if he would have liked to go back ten or twenty years later and tweaked some of these details.

Tristram wrote: "Tim Linkinwater also decides to make a clean breast of his feelings to Miss La Creevy, and his marriage proposal is one of the nicest speeches of the whole novel...."

Tristram wrote: "Tim Linkinwater also decides to make a clean breast of his feelings to Miss La Creevy, and his marriage proposal is one of the nicest speeches of the whole novel...."I loved this, too, Tristram. It's not often I actually write in books (unless I'm correcting typos - no OCD here!), but I had to put a big heart next to that paragraph. It was almost as nice as the earlier quote describing Miss La Creevy. What lovely passages they were!

Re: the betrothal of Miss La Creevy and Tim, I was surprised and, I admit, a bit disappointed. I thought for sure that she and Newman Noggs would end up together. Perhaps there was more of an age difference there than I imagined. I felt cheated that Newman's past wasn't spelled out more clearly, surprised that that past didn't intersect with any other characters but Ralph, and disappointed that his future had nothing more substantial to offer than an avuncular relationship with Kate and Nick's children. It's difficult to imagine that, alone, holding his interest.

Tristram wrote: "There are a lot of foreshadowing instances here. Do you think that the narrator is over-egging the pudding here, or do you consider the atmosphere befitting to the occasion?..."

Tristram wrote: "There are a lot of foreshadowing instances here. Do you think that the narrator is over-egging the pudding here, or do you consider the atmosphere befitting to the occasion?..."WAY TOO MUCH EGG IN THAT PUDDING! And annoying that an unrelated story, never before alluded to, is brought in at the eleventh hour to ... what? I'm not sure what Dickens was trying to do here. I thought it very contrived and unnecessary. Like the beams in the attic that I talked about in message 20, this suicide story would have been so much more effective if it had been mentioned somewhere earlier in the novel.

Perhaps I missed some nuance, but I still haven't made sense of Ralph. He was obviously already avaricious when he and Smike's mother were married. I think the novel would have worked better (and he would have made an even less-likable villain) had HE been the one to send Smike to Dotheboys. Then he'd have had reason to do business with Squeers, Squeers insistance on getting Smike back would have made more sense, and his hatred of Nicholas would have some validity. Brooker was an unnecessary complication in my mind.

The novel, and Ralph's character, are, though, perhaps more realistic because there are shades of gray, and things aren't as black and white as the readers might like. Suicides always leave those left behind with questions, and Ralph is no exception. Did he love Smike? Was he mourning his son, or the loss of his "evil empire"? Or both? Why, why, why did he have such a loathing for Nicholas and such a (comparative) soft spot for Kate? We never really got any insight into his heart or mind. Perhaps Ralph was complex, with a compelling back story, but what we saw was all we got. For such a major character, that's quite a let down.

At the end of NN we have all the little children visiting Smike's grave.

At the end of NN we have all the little children visiting Smike's grave. OT ends with the happy family visiting the memorial stone for Oliver's mother.

I don't remember a grave being visited at the end of PP - am I forgetting one?

I do hope Dickens will break the cycle and not have us all visiting a grave at the end of TOCS....

Mary Lou,

Mary Lou,After all those reasons you've given, I'm now more confident than ever OT is the better novel. Thanks for doing the heavy lifting. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "In the last segment, there was some discussion about the lack of foreshadowing when it came to Smike's paternity. I'm responding in this thread now that we know what became of Ralph.

For me, the ..."

Mary-Lou

I love your phrase “Pickwickian-sized banquet of coincidences.” What a great, and totally appropriate way, to phrase a Dickens comment or observation.

For me, the ..."

Mary-Lou

I love your phrase “Pickwickian-sized banquet of coincidences.” What a great, and totally appropriate way, to phrase a Dickens comment or observation.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "There are a lot of foreshadowing instances here. Do you think that the narrator is over-egging the pudding here, or do you consider the atmosphere befitting to the occasion?..."

W..."

Mary-Lou

Like Xan, I thank you for your incisive commentary and close reading of Ralph. You point out perplexing issues and unresolved or attended questions of his past, his motivations, and even his end of life. By pointing out the earlier mentions of the beams in the garret it does suggest to me that Dickens may well have had an early plot line in his head. In earlier comments I wondered about Dickens’s plotting.

As to your question of graveyards having a prominent role in Dickens’s novels, especially the end of a novel and what might be coming in future novels ... ... well, let’s wait and see. :-))

W..."

Mary-Lou

Like Xan, I thank you for your incisive commentary and close reading of Ralph. You point out perplexing issues and unresolved or attended questions of his past, his motivations, and even his end of life. By pointing out the earlier mentions of the beams in the garret it does suggest to me that Dickens may well have had an early plot line in his head. In earlier comments I wondered about Dickens’s plotting.

As to your question of graveyards having a prominent role in Dickens’s novels, especially the end of a novel and what might be coming in future novels ... ... well, let’s wait and see. :-))

Mary Lou wrote: "Re: the betrothal of Miss La Creevy and Tim, I was surprised and, I admit, a bit disappointed. I thought for sure that she and Newman Noggs would end up together."

Mary Lou wrote: "Re: the betrothal of Miss La Creevy and Tim, I was surprised and, I admit, a bit disappointed. I thought for sure that she and Newman Noggs would end up together."Me too! I thought Noggs and La Creevy were a great match. It didn't make sense to suddenly match La Creevy with Tim. Tim was introduced late, and we don't know much about him.

Noggs was a wonderful character who did good deeds for others. I wish too that Dickens had given him more attention and explained his past, particularly his relationship to Nick's father.

Chapter 65:

Chapter 65:"[The Nicklebys] made no claim to [Ralph's] wealth; and the riches for which he had toiled all his days, and burdened his soul with so many evil deeds, were swept at last into the coffers of the state, and no man was the better or the happier for them."

What?? Why not give Ralph's money to charity? I'm surprised that they let it go to the state and get wasted.

Alissa wrote: "Why not give Ralph's money to charity? I'm surprised that they let it go to the state and get wasted...."

Alissa wrote: "Why not give Ralph's money to charity? I'm surprised that they let it go to the state and get wasted...."Exactly what I thought. You'd think Dickens, of all people, would have had them use the money for charity.

Chapter 62

Chapter 62I thought this was the best written and most powerful chapter in the book, and I tip my hat to Chris Jones who narrated the chapter. The timbre of her voice caught the bleakness of this chapter perfectly.

I thought Ralph was the most fleshed out character in the book, this despite the time spent on Nicholas. Yes, much more could have been done with him, but the novel swirls around his every action. Almost every subplot and action in this story Ralph started on its way. Even all that Nicholas does is in reaction to what Ralph has set in motion. Perhaps he is the most underrated Dickens' character?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 62

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 62I thought this was the best written and most powerful chapter in the book, and I tip my hat to Chris Jones who narrated the chapter. The timbre of her voice caught the bleakness of this..."

He's definitely the hub of the story, which is why I was disappointed that we didn't get more answers about his motivations. It seems to me that the eponymous title was not the best choice (as fond as I am of alliteration). Perhaps something like "The Nickleby Narrative" would have been more inclusive of other members of the family, and therefore more accurate (and still alliterative!).

Chapter 63

Chapter 63Well, now, glad that's over. Where to begin.

Will Ned be marrying his brother? Only seems right given how well they get along.

Nicholas is now a partner??? What, two months after being hired? Is Tim a partner?

Tim has very comely feet?!?! What the hell is that?

Madeline is still a mannequin.

What did Dickens do, copy and paste that last chapter in OT and then make changes?

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 62

I thought this was the best written and most powerful chapter in the book, and I tip my hat to Chris Jones who narrated the chapter. The timbre of her voice caught the bleakness of this..."

Xan

Ralph is certainly a powerful character. With the exception of the title characters of the novels he is a very interesting and important character.

Your comment got me thinking. In OT I was intrigued with Nancy. I wonder if in Dickens’s earlier novels the supporting characters suffer a bit from a lack of recognition. Yes, OT is very well remembered, but how many characters beyond Oliver and Bumble get much thought? To what extent is it the same for NN?

It seems to me, to a certain extent, that the supporting characters of the later novels are better remembered.

I thought this was the best written and most powerful chapter in the book, and I tip my hat to Chris Jones who narrated the chapter. The timbre of her voice caught the bleakness of this..."

Xan

Ralph is certainly a powerful character. With the exception of the title characters of the novels he is a very interesting and important character.

Your comment got me thinking. In OT I was intrigued with Nancy. I wonder if in Dickens’s earlier novels the supporting characters suffer a bit from a lack of recognition. Yes, OT is very well remembered, but how many characters beyond Oliver and Bumble get much thought? To what extent is it the same for NN?

It seems to me, to a certain extent, that the supporting characters of the later novels are better remembered.

Yes, and this may be because of what the narrator does to them in the later books. Exaggeration and satire hit such a high pitch with some of them, that their mere introduction sears them into your memory.

Yes, and this may be because of what the narrator does to them in the later books. Exaggeration and satire hit such a high pitch with some of them, that their mere introduction sears them into your memory.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 61

I'm giving this chapter the subtitle Let's All Worship Nicholas Chapter.

Nicholas and Kate come to the conclusion that neither she nor he will actively pursue the fulfillment of their ..."

You are not alone, Xan, you are not alone!

I'm giving this chapter the subtitle Let's All Worship Nicholas Chapter.

Nicholas and Kate come to the conclusion that neither she nor he will actively pursue the fulfillment of their ..."

You are not alone, Xan, you are not alone!

Peter wrote: "For the boy who loses his courage after his escape from Dotheboys Hall, the bird is suggestive of the fact that its owner has been rendered unfit for his freedom in society. Like his bird in a cage, he will never be free. The only freedom possible is that found through death."

That's exactly what I thought, Peter: The little boy's dead bird shows that although Dotheboys Hall is finally shut down, there will hardly be a place in society for a friendless child, whose very parents seem to have forgotten him, and the fact that the boy is sleeping next to a dog seems to underline this. Madeline's and Tim's birds, however, can look forward to happier days, like their owners. - This somehow reminds me of the ending of Erich von Stroheim's great movie "Greed".

By the way, do you remember Mr. Squeers's reading about a boy who said he wished he were a donkey because then he would have parents who loved him? I found this a very moving detail, but I do have the feeling that a similar scene was also used by Dickens in Oliver Twist when Mr. Bumble was talking about a boy's "impertinence".

That's exactly what I thought, Peter: The little boy's dead bird shows that although Dotheboys Hall is finally shut down, there will hardly be a place in society for a friendless child, whose very parents seem to have forgotten him, and the fact that the boy is sleeping next to a dog seems to underline this. Madeline's and Tim's birds, however, can look forward to happier days, like their owners. - This somehow reminds me of the ending of Erich von Stroheim's great movie "Greed".

By the way, do you remember Mr. Squeers's reading about a boy who said he wished he were a donkey because then he would have parents who loved him? I found this a very moving detail, but I do have the feeling that a similar scene was also used by Dickens in Oliver Twist when Mr. Bumble was talking about a boy's "impertinence".

Mary Lou wrote: "Makes me wonder if CD was the type to write "The End" and then leave the finished stories in the past, or if he would have liked to go back ten or twenty years later and tweaked some of these details. "

His writing in instalments would probably have made it difficult for Dickens to think a lot about what he had written before giving it to his publishers, but I think that when the respective novel appeared as a whole, Dickens did some "tidying-up". I remember that my edition of Pickwick Papers included passages that were changed for the appearance as a complete novel. These were especially gory scenes that were removed, mostly from the inserted stories.

His writing in instalments would probably have made it difficult for Dickens to think a lot about what he had written before giving it to his publishers, but I think that when the respective novel appeared as a whole, Dickens did some "tidying-up". I remember that my edition of Pickwick Papers included passages that were changed for the appearance as a complete novel. These were especially gory scenes that were removed, mostly from the inserted stories.

Peter wrote: "I love your phrase “Pickwickian-sized banquet of coincidences.” What a great, and totally appropriate way, to phrase a Dickens comment or observation. "

It's a very good expression but somehow it makes me hungry ...

It's a very good expression but somehow it makes me hungry ...

Tristram wrote: "Peter wrote: "For the boy who loses his courage after his escape from Dotheboys Hall, the bird is suggestive of the fact that its owner has been rendered unfit for his freedom in society. Like his ..."

Yes. I often wonder to what extent Dickens’s portrayal of poor or orphaned children comes from his own experiences at Warren’s Blacking Factory.

Yes. I often wonder to what extent Dickens’s portrayal of poor or orphaned children comes from his own experiences at Warren’s Blacking Factory.

It would have been so easy for Dickens to close down Dotheboys and have us believe that the boys all made their way home to parents who loved them and weren't aware of Squeers' cruelty. I'm glad that he didn't do that, but it was very hard to read. I think the epilogue for some of the boys was much more emotional for me than Smike's death.

It would have been so easy for Dickens to close down Dotheboys and have us believe that the boys all made their way home to parents who loved them and weren't aware of Squeers' cruelty. I'm glad that he didn't do that, but it was very hard to read. I think the epilogue for some of the boys was much more emotional for me than Smike's death.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Will Ned be marrying his brother? Only seems right given how well they get along.

Nicholas is now a partner??? What, two months after being hired? Is Tim a partner?

Tim has very comely feet?!?! What the hell is that?

Madeline is still a mannequin."

Very good questions, especially the first one! Urban legend has it that there is always an evil twin, and sometimes it is hard to figure out which is the one. In the case of the Cheerybles, it would be harder, though, to find out who is the interesting twin.

Nicholas is now a partner??? What, two months after being hired? Is Tim a partner?

Tim has very comely feet?!?! What the hell is that?

Madeline is still a mannequin."

Very good questions, especially the first one! Urban legend has it that there is always an evil twin, and sometimes it is hard to figure out which is the one. In the case of the Cheerybles, it would be harder, though, to find out who is the interesting twin.

Unlike some of you, I did not really mind that we do not get any basic information on when and how Ralph really changed and why he has such a soft spot for Kate and so much hatred for Nicholas. Well, the loathing for Nicholas might become understandable to anyone who has read the book ;-)

But let's go back to Ralph: The fact that there are quite some things that are not cleared up and settled at the end of the novel makes him even more interesting as a character to me because it encourages me to fill the gaps according to my understanding of the character. I must say that I like it when a narrator does not try to fill every gap but leaves some of the imaginative work for me. It's like in real life where I also have to figure out why a person acts the way they act.

But let's go back to Ralph: The fact that there are quite some things that are not cleared up and settled at the end of the novel makes him even more interesting as a character to me because it encourages me to fill the gaps according to my understanding of the character. I must say that I like it when a narrator does not try to fill every gap but leaves some of the imaginative work for me. It's like in real life where I also have to figure out why a person acts the way they act.

Looking at the novel as a whole, it is probably obvious that NN stands more in the picaresque, funny tradition of PP than in that of OT, where Dickens tried to develop a whole story based on one major plot. OT is much darker and bitterer than its predecessor, wheras in NN the darker and more serious bits are very often attenuated by humour. All in all, it seems to me that Dickens had wanted to have the best of both worlds in NN - social criticism, real drama and plot as well as episodic digression, a large set of characters and side plots. The question is whether he really succeeded in creating something better ...

Tristram wrote: "Tim Linkinwater also decides to make a clean breast of his feelings to Miss La Creevy, and his marriage proposal is one of the nicest speeches of the whole novel. So nice, in fact, that I am going to insert it here..."

Tristram wrote: "Tim Linkinwater also decides to make a clean breast of his feelings to Miss La Creevy, and his marriage proposal is one of the nicest speeches of the whole novel. So nice, in fact, that I am going to insert it here..."I am so glad you did. That speech made me cry.

Mary Lou wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Why not give Ralph's money to charity? I'm surprised that they let it go to the state and get wasted...."

Mary Lou wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Why not give Ralph's money to charity? I'm surprised that they let it go to the state and get wasted...."Exactly what I thought. You'd think Dickens, of all people, would have had ..."

But then some good would have come of it, and that would have ruined the point that no good did.

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 63

Xan Shadowflutter wrote: "Chapter 63Well, now, glad that's over. Where to begin.

Will Ned be marrying his brother? Only seems right given how well they get along.

Nicholas is now a partner??? What, two months after bein..."

Tim and the comely feet was a nice touch. Ha!

Alissa wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Re: the betrothal of Miss La Creevy and Tim, I was surprised and, I admit, a bit disappointed. I thought for sure that she and Newman Noggs would end up together."

Alissa wrote: "Mary Lou wrote: "Re: the betrothal of Miss La Creevy and Tim, I was surprised and, I admit, a bit disappointed. I thought for sure that she and Newman Noggs would end up together."Me too! I thoug..."

Me three. I can't remember any foreshadowing of Tim's interest in LaCreevy, while she's definitely been in cahoots with Noggs. That marriage did take me by surprise. It almost feels like Dickens kind of forgot about Noggs for a while. But Tim's was such a lovely proposal I am willing to overlook the absent plotting. It drove the bizarre description of his nice feet right out of my mind.

The moment of bidding Nicholas farewell has arrived, and my parting reflections are influenced by wonderment at how different a novel, a good one, works on the reader (probably also a good one) depending on his or her age, and the circumstances of their lives. When we read OT a few months ago, it was the first time for me to realize what an interesting and complex female character Nancy is – this was doubtless also a result of our discussions here –, and this new reading of NN filled me with a lot of sympathy for Smike and his sad story, whereas in former readings, I concentrated on other elements of the story. For those of you who have read this book the second or even the third time, did you in any way experience it in a different way?

Maybe, however, this is a question for a thread on the novel as a whole. Let’s first take a look at the remaining five chapters, which can be done more quickly than usual, the chapters being a lot shorter and often merely a case of Dickens tying some lose ends together.

Chapter 61 focuses on how the Nickleby women react to the sad news of Smike’s death and on an agreement between Nicholas and his sister. As could be expected, Mrs. Nickleby releases a torrent of words on hearing about Smike’s death, the upshot of which is how glad she is that she was always so good friends with the poor boy, and that even though Nicholas must be very depressed, nobody can possibly know how deeply-felt her own grief is. Does this not endear even the most sceptical reader to Mrs. Nickleby?

I have often nagged about Nicholas’s being too arrogant, too smug, too hot-tempered, but in this Chapter there is a moment when I really like him, namely when he tells Miss La Creevy:

There is a lot of wisdom in these words, and they show that Nicholas is a caring person, and so they make up for a lot that has been annoying about Nicholas. Apart from that, he uses the remainder of the chapter to show himself in his usual way. There is a German word, ehrpusselig, which means that someone is extremely, often ridiculously touchy about what he or she regards as his honour. I don’t know if there is an English word for it, but there is definitely a character in an English novel whose picture would be next to the entry of the word in an English dictionary, and this character is Nicholas: In a very lengthy conversation – was there some insecurity as to how to fill the pages of the remaining instalment? – Nicholas and Kate come to the conclusion that neither she nor he will actively pursue the fulfilment of their love stories because both Madeline and Frank are wealthy, and they don’t want people to say or surmise that their wealth and their prospects – such as their close connections with the Cheeryble brothers – influenced Nick and Kate in their choices. When Kate tells her brother that Frank has actually proposed to her and she rejected him, Nicholas exclaims “That’s my own brave Kate! […] I knew you would.”

Do you think Nick’s stance on marrying into a wealthier sphere of life, a stance that is shared by his sister, too ehrpusselig considering that he actually loves Madeline? If you see it in the context of the novel, where quite some marriage decisions had to do with money, what do you think of Nick’s decision? What might the author have wanted us to think?

To do Nicholas justice, he is fully aware of Kate’s worth and the fact that even a very rich man would be highly rewarded by marrying her:

At the end of the chapter, Brother Charles tells Nicholas, among other things, about an appointment he (and Nicholas) have with Ralph.

How this appointment is kept is told in Chapter 62, which is the best-written chapter in this week’s instalment, in which we see Ralph “slinking off like a thief” from the Cheeryble’s house, “looking often over his shoulder […] as though he were followed in imagination or reality by someone anxious to question or detain him”. In fact, Ralph is under the impression that

With what is obviously something like a bad conscience, or some awareness of guilt, in his tow, Ralph passes a cemetery and Ralph remembers that somewhere among the graves there must be one of a suicide concerning whose death Ralph was once on a jury. There are a lot of foreshadowing instances here. Do you think that the narrator is over-egging the pudding here, or do you consider the atmosphere befitting to the occasion?

When Ralph comes to his own house and realizes how dark and solitary it looks, this reminded me of another situation in which a miser enters his own home during a dark and frosty night. Ralph can hardly convince himself to unlock his house, and when he finally does so, entering, “he felt as though to shut it again would be to shut out the world.”

Inside, he starts musing on how all his partners in crime (or infamy) have fallen away from him, but his most bitter thought is that his own child fell victim to his actions and that he hurried his own son into an early grave through his own persecution. But wait, this is not really the bitterest thought: What vexes him more is that Smike had died with Nicholas beside him, loving Nicholas and thinking him an angel instead of hating and despising him as Ralph would have taught him if he had had the chance to get to know his son. He also thinks that maybe, he and his son would have been happy together, and that his wife’s flight and his son’s supposed death might have contributed to making him such a harsh and hostile person – but first and foremost, what is galling him is his awareness of the ties of love and friendship between Nicholas and Smike. Do you think that Ralph’s descend into misanthropy and meanness was helped on by his thinking that his son was dead and the flight of his wife? Could he have been a different man? And why does Nicholas play such a big role in his reflections still?

The narrator gives the following explanation:

Ralph then decides to rob the Cheerybles, and his nephew (!), of their last triumph, namely of pouring out their mercy and compassion. And since there seems no devil to help him, he remembers the suicide whose death he had to examine years ago, and he sees “the victory achieved by that heap of clay” in his act of self-destruction. This prompts him to go into the very attic room in which Smike was hidden years ago and to hang himself, once more venting his hatred for humanity in a little speech that is almost Shakespearean:

Where do this little speech and Ralph’s final decision move the character on our little list of villains?

When he is later found, it turns out – at least to us and the narrator – that he hung himself beneath the trap-door “in the very place to which the eyes of his son, a lonely, desolate, little creature, had so often been directed in childish terror, fourteen years before.”