The Old Curiosity Club discussion

The Old Curiosity Shop

>

TOCS Chapters 70-73

Chapter the Seventy-first

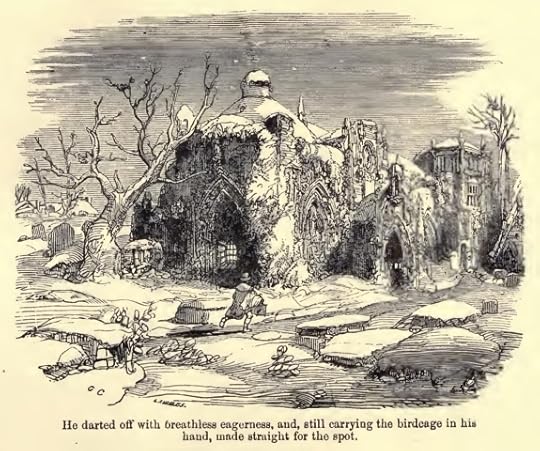

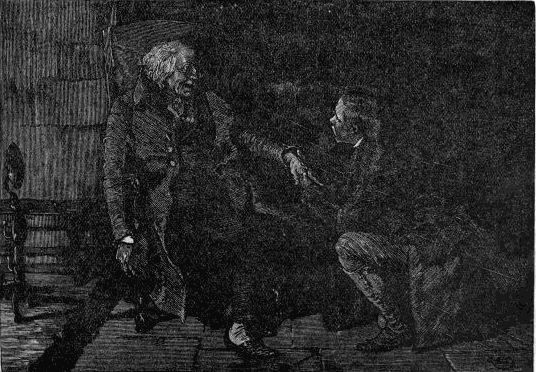

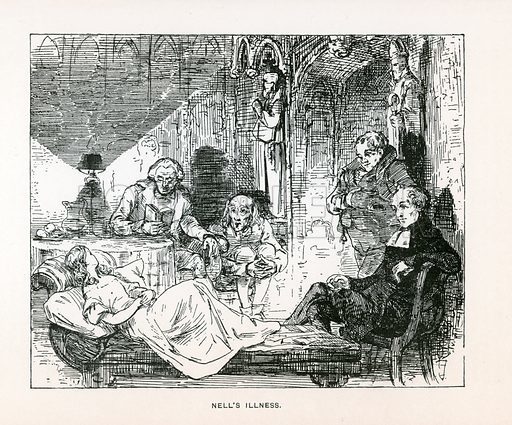

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was? All we know is that the figure was emitting a “mournful sound.” It is not until the next paragraph that we learn that the figure was that of an old man and that he gazed “at the mouldering embers” and the “failing light and dying fire ... [a]shes, and dust, and ruin!” Kit recognizes the figure as Nell’s grandfather and says “ [d]ear master. Speak to me” to which Trent replies “[t]his is another! - How many of these spirits there have been to-night.” Kit inquires about Nell and what follows is an eerie conversation that oscillates between silence and questions, reality and illusion. The grandfather says that Nell has called in her sleep, that she is quietly sleeping now, and mentions that birds are dead, that Nell used to feed the birds, and that the birds were never afraid of Nell. This is all rather confusing. As readers, we feel the tension. Is Nell asleep? Is she dead? Into the room comes Mr Garland and his friend, the schoolmaster, and the bachelor.

Thoughts

This is the chapter that Dickens has been preparing us for and now we have arrived. Why do you think Dickens has not immediately allowed the reader to learn the specifics of Nell’s death? Do you think this decision was correct?

Nell’s grandfather was first seen by Kit staring into the “mouldering embers” of the fire. Where have we already seen a similar tableau of a person staring into a fire?? Can you draw any connections or comparisons between the events?

The new arrivals begin a gentle intervention with Nell’s grandfather. Through this technique Dickens is able to fill in the backstory of Nell and her grandfather as the various people in the room speak. We learn from the bachelor that he is the grandfather’s younger brother who loved him dearly but was “long unseen, long separated” from his brother. We learn that he has come back to be with his brother and to be to him what his older brother was to him long ago.

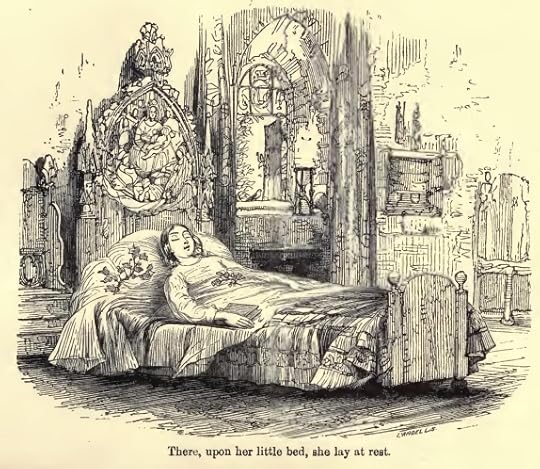

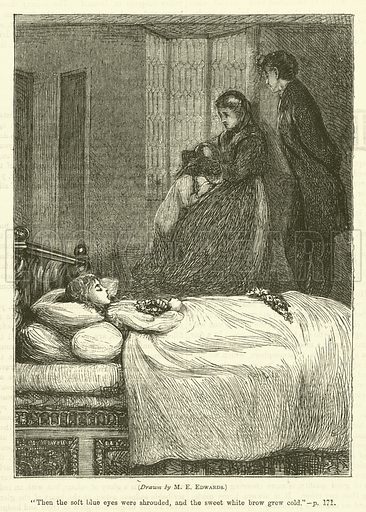

Nell is dead. We read that her appearance was beautiful and calm and free from any trace of pain. Indeed, “[s]he seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God.” Dickens repeats a version of the phrase “she was dead” and juxtaposes it with the fact that her bird that Kit has brought from London “was still nimbly in its cage; [while] the strong heart of its child-mistress was mute and motionless for ever.” Earlier in the novel it was mentioned that Dickens seemed to focus on a person’s hands. Here, we see the culmination of this image as we read that Nell’s grandfather held her “small hand tightly folded to his breast ... it was the hand she had stretched out to him with her last smile - the hand that she had lead him on through all their wanderings.”

Thoughts

Little Nell is dead. What are your impressions on how Dickens presented her death to the reader? After such a long decline in health, did you find the Nell’s death scene to be effectively presented or very anti-climatic? Why/why not?

Did you guess that the bachelor was related to Nell? If so, what were the hints?

Did you find the comparison between Nell and her bird to be an effective bit of writing or too much pathos?

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was? All we know is that the figure was emitting a “mournful sound.” It is not until the next paragraph that we learn that the figure was that of an old man and that he gazed “at the mouldering embers” and the “failing light and dying fire ... [a]shes, and dust, and ruin!” Kit recognizes the figure as Nell’s grandfather and says “ [d]ear master. Speak to me” to which Trent replies “[t]his is another! - How many of these spirits there have been to-night.” Kit inquires about Nell and what follows is an eerie conversation that oscillates between silence and questions, reality and illusion. The grandfather says that Nell has called in her sleep, that she is quietly sleeping now, and mentions that birds are dead, that Nell used to feed the birds, and that the birds were never afraid of Nell. This is all rather confusing. As readers, we feel the tension. Is Nell asleep? Is she dead? Into the room comes Mr Garland and his friend, the schoolmaster, and the bachelor.

Thoughts

This is the chapter that Dickens has been preparing us for and now we have arrived. Why do you think Dickens has not immediately allowed the reader to learn the specifics of Nell’s death? Do you think this decision was correct?

Nell’s grandfather was first seen by Kit staring into the “mouldering embers” of the fire. Where have we already seen a similar tableau of a person staring into a fire?? Can you draw any connections or comparisons between the events?

The new arrivals begin a gentle intervention with Nell’s grandfather. Through this technique Dickens is able to fill in the backstory of Nell and her grandfather as the various people in the room speak. We learn from the bachelor that he is the grandfather’s younger brother who loved him dearly but was “long unseen, long separated” from his brother. We learn that he has come back to be with his brother and to be to him what his older brother was to him long ago.

Nell is dead. We read that her appearance was beautiful and calm and free from any trace of pain. Indeed, “[s]he seemed a creature fresh from the hand of God.” Dickens repeats a version of the phrase “she was dead” and juxtaposes it with the fact that her bird that Kit has brought from London “was still nimbly in its cage; [while] the strong heart of its child-mistress was mute and motionless for ever.” Earlier in the novel it was mentioned that Dickens seemed to focus on a person’s hands. Here, we see the culmination of this image as we read that Nell’s grandfather held her “small hand tightly folded to his breast ... it was the hand she had stretched out to him with her last smile - the hand that she had lead him on through all their wanderings.”

Thoughts

Little Nell is dead. What are your impressions on how Dickens presented her death to the reader? After such a long decline in health, did you find the Nell’s death scene to be effectively presented or very anti-climatic? Why/why not?

Did you guess that the bachelor was related to Nell? If so, what were the hints?

Did you find the comparison between Nell and her bird to be an effective bit of writing or too much pathos?

Chapter the Seventy-second

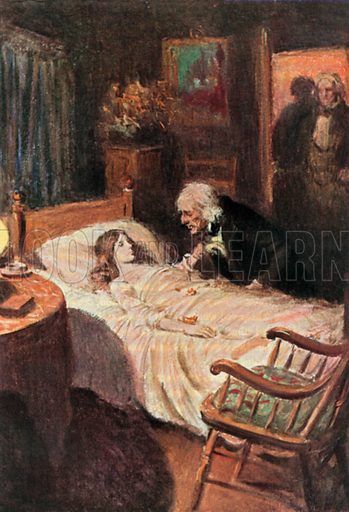

We learn that Nell has been dead for two days, and that her final hours were not spent in pain. In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they walked by the riverside earlier in her travels. This is a rather brief reference to the girls and perhaps Dickens needed to expand this somewhat. In last week’s comments there were comments about the young girls. What do you think?

We read that Nell recalled Kit and wished that someone would take her love to him. The little boy who befriended Nell talked of his dream that she would be restored to the town. Nell’s grandfather, who has lost touch with reality, accompanies the young boy to gather flowers for Nell’s bed. The village people show great sympathy and gentleness towards the grieving grandfather. The townspeople accompany Nell to her gravesite in the church. Nell is buried in the church and Dickens writes that the people “left the child with God.”

Thoughts

Dickens has been signalling for many chapters that Nell was going to die. We have discussed his use of foreshadowing and pathos. What is your response to the fact that Nell has finally passed away?

The next day Nell’s grandfather is told that Nell is dead. When he hears and realizes the news “he fell down among them like a murdered man.” The old man pined and moped for days and wandered about and could find no comfort. For a few paragraphs Dickens draws out the event of the old man’s wandering mind, his broken spirit, and the fact that he one day puts on his travelling attire and goes to sit by Nell’s grave. In order to increase the sorrow and loss of Nell Dickens writes the epistrope “She will come tomorrow” at the end of two consecutive paragraphs. From this point on grandfather Trent spends his days with Nell, prepared for a journey with “his knapsack on his back, his staff in his hand, her own straw hat and her little basket” beside him. One day he does not return from his vigil in the church and he is found lying dead upon [Nell’s] stone. The chapter ends with Dickens reuniting Nell and her grandfather who now “slept together.”

Thoughts

Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?

I have been harsh on Nell’s grandfather. I do feel, however, that Dickens softened my feelings towards Trent in the past few chapters. What was your response to the grandfather’s death?

Overall, did you find their deaths what you expected or were you surprised in any way?

We learn that Nell has been dead for two days, and that her final hours were not spent in pain. In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they walked by the riverside earlier in her travels. This is a rather brief reference to the girls and perhaps Dickens needed to expand this somewhat. In last week’s comments there were comments about the young girls. What do you think?

We read that Nell recalled Kit and wished that someone would take her love to him. The little boy who befriended Nell talked of his dream that she would be restored to the town. Nell’s grandfather, who has lost touch with reality, accompanies the young boy to gather flowers for Nell’s bed. The village people show great sympathy and gentleness towards the grieving grandfather. The townspeople accompany Nell to her gravesite in the church. Nell is buried in the church and Dickens writes that the people “left the child with God.”

Thoughts

Dickens has been signalling for many chapters that Nell was going to die. We have discussed his use of foreshadowing and pathos. What is your response to the fact that Nell has finally passed away?

The next day Nell’s grandfather is told that Nell is dead. When he hears and realizes the news “he fell down among them like a murdered man.” The old man pined and moped for days and wandered about and could find no comfort. For a few paragraphs Dickens draws out the event of the old man’s wandering mind, his broken spirit, and the fact that he one day puts on his travelling attire and goes to sit by Nell’s grave. In order to increase the sorrow and loss of Nell Dickens writes the epistrope “She will come tomorrow” at the end of two consecutive paragraphs. From this point on grandfather Trent spends his days with Nell, prepared for a journey with “his knapsack on his back, his staff in his hand, her own straw hat and her little basket” beside him. One day he does not return from his vigil in the church and he is found lying dead upon [Nell’s] stone. The chapter ends with Dickens reuniting Nell and her grandfather who now “slept together.”

Thoughts

Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?

I have been harsh on Nell’s grandfather. I do feel, however, that Dickens softened my feelings towards Trent in the past few chapters. What was your response to the grandfather’s death?

Overall, did you find their deaths what you expected or were you surprised in any way?

Chapter the Seventy-third

Well, here we are at the end of another Dickens novel. It has been quite the story and we have experienced many diverse responses to the story of Nell Trent. It remains only for me to tie up the loose ends and send our remaining characters into their futures. There may be some surprises and twists of fate. No doubt there will be an instance or two of poetic justice as well. Here goes ... and if I miss anything please feel free to fill in the blanks.

As Dickens says in the first paragraph of this final chapter:

“The magic reel, which rolling on before, has lead its chronicler thus far, now slackens in its pace, and stops. It lies before the goal; the pursuit is at an end.”

Mr Sampson ends up wearing a prison suit of somber grey, has his hair cut short, and lives on gruel and light soup. Prison gives him exercise on the prison treadmill and he gets to wear handcuffs. He is debarred. Later, rumour has it he again joins with Sally and they live unhappy and impoverished lives.

Sally Brass ends up poorly. She and Sampson spend their days in poverty scrounging for food.

Quilp’s body is found and it is generally held that he committed suicide. He was buried with a stake through his heart in the centre of four lonely roads.

Tom Scott darkened the window of a courtroom by standing on his head upon a window sill.

Mrs Quilp finds love again and now, being rich because Quilp did not leave a will, finds love with a “smart young fellow” and lived a merry life on the dead dwarf’s money.

Mr and Mrs Garland and Mr Able lived happily and Mr Able falls in love, marries, and has a family.

The pony leads a wonderful life and “lived in clover” and passes only after giving the vet one good final kick.

Our friend Mr Swiveller recovers from his illness and sends the Marchioness, now named Sophronia Sphinx, to school. When she turns 19 they marry. Dick wonders about the Marchioness’s parentage but that question does not give him uneasiness.

The gamblers Issac List and Jowl become connected with Frederick Trent and all three are punished. Frederick Trent's body is later found in Paris, but is never claimed.

The younger brother, or the single gentleman, went forth in the former footsteps of his bother and Nell to seek out and reward all who were kind to them. The schoolmaster was a poor schoolmaster no more due to the younger brother’s benevolence. Whether Mrs Jarley created a wax figure of Nell remains a mystery.

And Kit ... well, he marries Barbara, and they have children who bear the names of many of the good characters in the novel. Time heals, and time changes one’s life. The Old Curiosity Shop’s location becomes obscure and then almost forgotten.

And finally, and this is my guess, Nell’s bird has a long and happy life with Kit and Barbara.

Thoughts

Were you surprised with the fate of any of the characters? If so who, and why?

Reflections

There are so many ways to approach TOCS and I have puzzled over how to summarize the novel. We have talked a great deal about Nell’s innocence and the long, long, melodramatic journey to her death. What has often struck me about Dickens’s early novels is how his characters are so frequently slotted into either being good, kind, generous, and perhaps slightly naive, and those characters who are dastardly, evil, scheming, and very frequently sadistic. In TOCS there appears a very clear division of characters, one that I would characterize as a duality. Nell is good, kind and innocent; Quilp is sadistic, sexual, and aggressive.

We see no alteration in the character of Little Nell. That is, in part, why she is often dismissed as being rather flat, bland, and unbelievable. I have always liked Nell, not only because she is so unworldly good, but because I still hope there are such people whose pilgrimages through life will bring good to the world.

During our reading of this book I have been struck with the number of times Shakespeare seems to have poked his way into my mind. Little Nell and her grandfather remind me of Cordelia and Lear. Now Cordelia is much more of a rounded character, much more assertive, and much grander in scale than our Little Nell, but the relationship between Cordelia and Lear and Nell and her grandfather seem similar to me at the end of their lives. Lear and Nell’s grandfather’s mind both drift into confusion. Like King Lear, Nell’s grandfather is nursed back to some form of emotional health by his daughter. Both Cordelia and Nell unreservedly love Lear and the grandfather. Both women evoke drastic measures to demonstrate their love. For Cordelia, it is to tell the truth and then later to ignore the conditions of her banishment in order to prove her love and attempt to save her father (and England). For Nell, it is to remove her grandfather from danger on more than one occasion and to administer to his weaknesses. Lear’s howl of “never, never ...” points to his anguish. Nell’s grandfather is much more passive than Lear, but the loss of Nell, and his mournful waiting for her at her grave, speak loudly in his actions.

TOCS examines the question of how a good person can preserve their innocence even when confronted by constant evil. Dickens assures his readers that there are people of good nature who we will meet along our paths in life. A simple farm family will be willing to share a meal, a lonely and poor schoolmaster will offer to share a residence, a poor man will be willing to take two strangers to a place of warmth, an itinerant business woman will offer food and a job. Such kindness does exist in the world. Nell preserves her innocence and goodness in the face of evil. Ultimately, she dies. If TOCS is an allegory, it is depressing. If TOCS is a fairy tale, it is a bleak one.

In our century it is hard, perhaps impossible, to disagree with Oscar Wilde’s assessment that one must have a heart of stone not to laugh at Little Nell. I wonder, however, if Wilde’s

character Dorian Gray would not have benefited from reading TOCS. The price Dorian paid for his lifestyle was his death, and the death of other innocent people. Nell dies too, but whose legacy would one aspire to be in their own life, Nell’s or Dorian’s?

Ultimately, I think we all applaud the renewed Scrooge, we are happy that Dick Swiveller has changed, that the Marchioness has been rescued from her subterranean home, and that Kit has found love, marriage, and the joy of children. Dickens tells us in the final chapter that over time Kit cannot recall the exact location of The Old Curiosity Shop. Perhaps the physical location of the shop is not as important as its place within Kit’s memory and the memory of the novel’s readers.

I eagerly await your final comments this coming week.

Well, here we are at the end of another Dickens novel. It has been quite the story and we have experienced many diverse responses to the story of Nell Trent. It remains only for me to tie up the loose ends and send our remaining characters into their futures. There may be some surprises and twists of fate. No doubt there will be an instance or two of poetic justice as well. Here goes ... and if I miss anything please feel free to fill in the blanks.

As Dickens says in the first paragraph of this final chapter:

“The magic reel, which rolling on before, has lead its chronicler thus far, now slackens in its pace, and stops. It lies before the goal; the pursuit is at an end.”

Mr Sampson ends up wearing a prison suit of somber grey, has his hair cut short, and lives on gruel and light soup. Prison gives him exercise on the prison treadmill and he gets to wear handcuffs. He is debarred. Later, rumour has it he again joins with Sally and they live unhappy and impoverished lives.

Sally Brass ends up poorly. She and Sampson spend their days in poverty scrounging for food.

Quilp’s body is found and it is generally held that he committed suicide. He was buried with a stake through his heart in the centre of four lonely roads.

Tom Scott darkened the window of a courtroom by standing on his head upon a window sill.

Mrs Quilp finds love again and now, being rich because Quilp did not leave a will, finds love with a “smart young fellow” and lived a merry life on the dead dwarf’s money.

Mr and Mrs Garland and Mr Able lived happily and Mr Able falls in love, marries, and has a family.

The pony leads a wonderful life and “lived in clover” and passes only after giving the vet one good final kick.

Our friend Mr Swiveller recovers from his illness and sends the Marchioness, now named Sophronia Sphinx, to school. When she turns 19 they marry. Dick wonders about the Marchioness’s parentage but that question does not give him uneasiness.

The gamblers Issac List and Jowl become connected with Frederick Trent and all three are punished. Frederick Trent's body is later found in Paris, but is never claimed.

The younger brother, or the single gentleman, went forth in the former footsteps of his bother and Nell to seek out and reward all who were kind to them. The schoolmaster was a poor schoolmaster no more due to the younger brother’s benevolence. Whether Mrs Jarley created a wax figure of Nell remains a mystery.

And Kit ... well, he marries Barbara, and they have children who bear the names of many of the good characters in the novel. Time heals, and time changes one’s life. The Old Curiosity Shop’s location becomes obscure and then almost forgotten.

And finally, and this is my guess, Nell’s bird has a long and happy life with Kit and Barbara.

Thoughts

Were you surprised with the fate of any of the characters? If so who, and why?

Reflections

There are so many ways to approach TOCS and I have puzzled over how to summarize the novel. We have talked a great deal about Nell’s innocence and the long, long, melodramatic journey to her death. What has often struck me about Dickens’s early novels is how his characters are so frequently slotted into either being good, kind, generous, and perhaps slightly naive, and those characters who are dastardly, evil, scheming, and very frequently sadistic. In TOCS there appears a very clear division of characters, one that I would characterize as a duality. Nell is good, kind and innocent; Quilp is sadistic, sexual, and aggressive.

We see no alteration in the character of Little Nell. That is, in part, why she is often dismissed as being rather flat, bland, and unbelievable. I have always liked Nell, not only because she is so unworldly good, but because I still hope there are such people whose pilgrimages through life will bring good to the world.

During our reading of this book I have been struck with the number of times Shakespeare seems to have poked his way into my mind. Little Nell and her grandfather remind me of Cordelia and Lear. Now Cordelia is much more of a rounded character, much more assertive, and much grander in scale than our Little Nell, but the relationship between Cordelia and Lear and Nell and her grandfather seem similar to me at the end of their lives. Lear and Nell’s grandfather’s mind both drift into confusion. Like King Lear, Nell’s grandfather is nursed back to some form of emotional health by his daughter. Both Cordelia and Nell unreservedly love Lear and the grandfather. Both women evoke drastic measures to demonstrate their love. For Cordelia, it is to tell the truth and then later to ignore the conditions of her banishment in order to prove her love and attempt to save her father (and England). For Nell, it is to remove her grandfather from danger on more than one occasion and to administer to his weaknesses. Lear’s howl of “never, never ...” points to his anguish. Nell’s grandfather is much more passive than Lear, but the loss of Nell, and his mournful waiting for her at her grave, speak loudly in his actions.

TOCS examines the question of how a good person can preserve their innocence even when confronted by constant evil. Dickens assures his readers that there are people of good nature who we will meet along our paths in life. A simple farm family will be willing to share a meal, a lonely and poor schoolmaster will offer to share a residence, a poor man will be willing to take two strangers to a place of warmth, an itinerant business woman will offer food and a job. Such kindness does exist in the world. Nell preserves her innocence and goodness in the face of evil. Ultimately, she dies. If TOCS is an allegory, it is depressing. If TOCS is a fairy tale, it is a bleak one.

In our century it is hard, perhaps impossible, to disagree with Oscar Wilde’s assessment that one must have a heart of stone not to laugh at Little Nell. I wonder, however, if Wilde’s

character Dorian Gray would not have benefited from reading TOCS. The price Dorian paid for his lifestyle was his death, and the death of other innocent people. Nell dies too, but whose legacy would one aspire to be in their own life, Nell’s or Dorian’s?

Ultimately, I think we all applaud the renewed Scrooge, we are happy that Dick Swiveller has changed, that the Marchioness has been rescued from her subterranean home, and that Kit has found love, marriage, and the joy of children. Dickens tells us in the final chapter that over time Kit cannot recall the exact location of The Old Curiosity Shop. Perhaps the physical location of the shop is not as important as its place within Kit’s memory and the memory of the novel’s readers.

I eagerly await your final comments this coming week.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventieth

Peter wrote: "Chapter the SeventiethHello fellow Curiosities

This week’s chapters bring us to the conclusion of The Old Curiosity Shop. Within these chapters we will learn the fate of Little Nell, but I suspe..."

He laid his hand upon the latch, and put his knee against the door. Inside he sees a glimmering of a fire. He enters the room. And here ends the chapter and the weekly instalment.

Wasn't this just the perfect tease to the next installment? I thought so, and kept on reading. Big mistake!

Dickens draws out the arrival of Kit and the others for many paragraphs. Did you find this use of suspense effective or annoying?

Had I given myself some space between the last section and these chapters, I think I would have appreciated Dickens's drawing out the ending a little more. However, I loved what Dickens was doing in this chapter. It was a little later where the Dickens motif had begun to take its toll on me (Grandfather's bemoaning Nell's demise)*. In fact, what you have quoted, I loved every single one of those references. It may be seen as overdone, but it was effective. The repetition of allusion and symbolism throughout the novel, I read to be useful and his way of creating a thread to help me as a reader navigate in and around this novel in a more efficient manner. However, this same treatment (the repetition factor) shown to these characters, I wasn't as receptive to it, thinking it railroaded the characters instead of giving them dimension.

*It could very well also have been attributed to Grandfather, alone. I felt it difficult to sympathize with him beyond somebody who was grieving.

To what extent did you find the mention of “one solitary light” that “sparkled like a star” suggestive of the journey of the shepherds and then the wise men in the Bible? In what ways? How effective was the image to you?

Peter, I didn't think Dickens gave me room for any other suggestion. He had me cornered, the solitary light and sparkling star coming at me deeply rooted in allegory. I thought it was perfect, actually; the magical and allegorical finally coming together nicely, giving me solace in Nell's passing, personally.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-first

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-firstKit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was? All we know i..."

Why do you think Dickens has not immediately allowed the reader to learn the specifics of Nell’s death? Do you think this decision was correct?

I think to add another layer to the tension already built from the prior installment's. Dickens sure enjoys keeping his readers waiting with baited breath, doesn't he? I was all the more confused; both by the anticipation and the reality of Nell's passing. Even in these last moments with the novel, I still couldn't count on Grandfather to give me a straight forward answer...was she, or was she not dead...and, had she been dead for two days already?

I think it was a good decision to keep the reader curious, though it was a terrible decision allowing Grandfather to be the source of our answers.

Nell’s grandfather was first seen by Kit staring into the “mouldering embers” of the fire. Where have we already seen a similar tableau of a person staring into a fire?? Can you draw any connections or comparisons between the events?

Lizzie Hexam comes to mind, Peter... I'm not sure of the comparison between Lizzie and Grandfather looking into the fire, but what if it symbolizes a hearth that leaves both characters cold, having lost people (Lizzie her father) important to them? Or, maybe looking into the fire represents a moment of great reflection and change; as the pieces of coal and embers transform to ashes, so do these characters, respectively?

What about Mr. Dombey...didn't we first meet him sitting in a corner looking onto his newborn son, who was positioned between his father and a hearth fire? Dombey looking at him and reflecting about the child's future is one story; the baby crying and throwing his fists up in the air, against a backdrop of flames, telling us another story.

After such a long decline in health, did you find the Nell’s death scene to be effectively presented or very anti-climatic? Why/why not?

Oh, Peter. I feel so bad about this, but I thought her death too was anticlimactic, and mostly due to Grandfather. Had Dickens skipped the Kit/Grandfather interaction and gone straight to Nell, it would have been so much better. The inclusion of Grandfather from the onset just made the situation all the more convoluted in delivery.

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-second

Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-secondWe learn that Nell has been dead for two days, and that her final hours were not spent in pain. In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they ..."

We learn that Nell has been dead for two days, and that her final hours were not spent in pain.

I'm not sure I understood if Dickens wrote about Nell's passing as if it had already happened, or if she was had been dead for two days before Kit arrived. I had to read it twice. There was that whole scene where the Stranger, Kit and the Bachelor, had surrounded Nell in her bed, making her last moments joyous and full of love, it was a great moment for me.

What is your response to the fact that Nell has finally passed away?

I was happy for her, happy for her because she finally had peace. She beared a burden no child should have to at her age, she saw things she shouldn't have seen; she endured treatment by adults that no child should have to experience. Nell was alone, the adult in the room when nobody else could be relied upon; and yet, she never faltered in compassion and love towards others...she was not of this Earth, it was clear. It was time for her to go home, wherever that may be for her.

What was your response to the grandfather’s death?

Did Dickens want his readers to believe that Grandfather would be there right next to Nell in the after-life...because I can't see them ending up in the same place, did you?

Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-first

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was?..."

Hi Ami

Thank you for your thoughtful responses. I found these chapters somewhat difficult to present. We all know that Nell will die. The big question to me was how would people respond to Dickens’s handling of the situation.

You are right. The symbolic and the allegorical elements are swirling about. Add to that the heavy weight of melodrama that we have been carrying for quite some time, and we could have been headed for either a momentous crash or a somewhat rocky ending. As it is, I think Dickens handled the last chapters with remarkable restraint, considering what he might have chosen to do.

I enjoyed your comments of how fire and ash have been woven throughout the novels of Dickens. While the simple formula of hearty fire - happy home and cold fire - cold hearts is a general trope, Dickens always seems to give the situation a special stamp. I was thinking of the part in TOCS where we see Nell and her grandfather warmed by the fire of the furnace while the furnace keeper looks at the embers. You have broadened and deepened the image for us.

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was?..."

Hi Ami

Thank you for your thoughtful responses. I found these chapters somewhat difficult to present. We all know that Nell will die. The big question to me was how would people respond to Dickens’s handling of the situation.

You are right. The symbolic and the allegorical elements are swirling about. Add to that the heavy weight of melodrama that we have been carrying for quite some time, and we could have been headed for either a momentous crash or a somewhat rocky ending. As it is, I think Dickens handled the last chapters with remarkable restraint, considering what he might have chosen to do.

I enjoyed your comments of how fire and ash have been woven throughout the novels of Dickens. While the simple formula of hearty fire - happy home and cold fire - cold hearts is a general trope, Dickens always seems to give the situation a special stamp. I was thinking of the part in TOCS where we see Nell and her grandfather warmed by the fire of the furnace while the furnace keeper looks at the embers. You have broadened and deepened the image for us.

Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-first

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was?..."

Yes. For Kit to find Nell dead would have been much more effective and striking. Grandfather should have been in a corner mourning Nell’s passing.

Kit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the figure was?..."

Yes. For Kit to find Nell dead would have been much more effective and striking. Grandfather should have been in a corner mourning Nell’s passing.

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-first

Peter wrote: "Ami wrote: "Peter wrote: "Chapter the Seventy-firstKit’s eyes first perceive a figure. Did you note that Dickens does not initially indicate who the figure is, or even suggest what the sex of the..."

As it is, I think Dickens handled the last chapters with remarkable restraint, considering what he might have chosen to do.

There were too many moving parts in these chapters. The pacing too, was questionable, most especially when the attention was placed Grandfather when he could have put the light on Nell...the main character (as we've already established). You are quite right about the restraint Dickens shows in these chapters, I felt it while reading it was that tangible for me.

I found these chapters somewhat difficult to present. We all know that Nell will die. The big question to me was how would people respond to Dickens’s handling of the situation.

I would find them difficult to present as well; although, you did a phenomenal job facilitating points worthy of discussion. Speaking of, I forgot to address your question about the Bachelor... I was left wondering why he wasn't included in the final chapter And, I missed the clue that shed light on his being a relation to Nell.

I was thinking of the part in TOCS where we see Nell and her grandfather warmed by the fire of the furnace while the furnace keeper looks at the embers.

A-ha! Hmmm. So, would the parallel here be that the furnace keeper has reason to keep the embers from dying out because there is need to keep the fire burning (keeping people warm), whereas Grandfather was just biding his time, no longer a need to keep the hearth warm?

WARNING: The following commentary is brutally honest and may displease some of our members. In fact, one of our members (cough-Kim-cough) may want to skip this entirely, or have medical supervision while reading it, as it's sure to cause too much stress to her tender heart.

WARNING: The following commentary is brutally honest and may displease some of our members. In fact, one of our members (cough-Kim-cough) may want to skip this entirely, or have medical supervision while reading it, as it's sure to cause too much stress to her tender heart. Peter wrote: "As it is, I think Dickens handled the last chapters with remarkable restraint..."

Really? I would have hated to see what it would have looked like if he'd really let loose!

First, let me say, Peter, what a wise choice the other moderators made when they welcomed you to their ranks. You always give us something new to consider, and make the text deeper and more meaningful with your summaries and comments.

As for the conclusion of TOCS, I feel like quite the traitor, and am even surprised to hear myself say it, but I truly disliked this book. These last few chapters made it easier for me to state that shocking position out loud.

Many of you probably remember that I prefer dialogue to description, and I get impatient when Dickens takes too long to set the stage, even when he does it brilliantly. As Peter said, "Dickens, for his part, draws out the journey." Boy, did he! He took an entire chapter to accomplish what he could have said in one paragraph. For the love of God, just get on with it! Little bores me more than the description of travel when the plot isn't going anywhere.

Finally our heroes reach their destination, and.... nothing. Okay, it's a cliff-hanger. I get it. So we read on into the next chapter and... riddles! I AM NOT ENJOYING THIS JOURNEY. There is no pleasure for me in the anticipation. Stick a fork in me; I'm done!

Eventually, of course, we find out that Nell is, indeed, dead. Once he gets around to it, Dickens feels the need to repeat it over and over again. Where were those declarative statements earlier, Chuck?? To heck with Nell's suffering, or that of the many mourners. The only thing I felt at this point was great relief that MY suffering as a reader was finally over. Now, I really had nothing against little Nell. No, she wasn't all that exciting to read about, but she had gumption and handled her situation the best she could, and admirably for someone of her tender years who was afraid to trust in the adults around her. Ami put it all very nicely. It's a shame she died. I wish it had been written in a way that I felt more than I did.

What could be worse than the epic death of Little Nell?? The coddling of her selfish, horrible grandfather! Anyone remember that famous scene from the movie "Moonstruck" in which Cher slaps Nicholas Cage across the face and says, "Snap out of it!"? (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0x-fk...) I kept waiting for somebody to do that with Gramps. Alas, it never happened. This was an old man in the Victorian age. He'd seen death before, lots of times. Including Nell's sainted grandmother and mother before her. Death happens. Yes, it's sad and sometimes tragic. But was Grandpa, who actually stole from Nell, and forced her into homelessness really worthy of such tender handling from the townsfolk? I'd like to suppose it's meant to reflect on their goodness as much as his grief, but I really don't know that Dickens intended it that way. More likely, we're meant to feel that if someone as good as Nell could love Grandpa, we should love him, too. Which, I guess, brings us back to the Nell-as-Christ theme. But it's all too much for me at this point. I'm obviously a flawed sinner because I have no patience for Grandpa or his mourning. Much of my time reading this chapter was spent rolling my eyes. When Grandpa finally died (and yes, Ami, one has to wonder if they're really spending eternity together) I felt like we should all be at the Jolly Sandboys, exchanging high-fives and toasting his demise. I'm a horrible person, but there it is.

The final chapter tying everything up in a tidy bow was nice for resolution but, stylistically speaking, I wish Dickens had plotted out the novel in such a way that some of this could have been resolved as part of the narrative rather than as an epilogue.

The final chapter tying everything up in a tidy bow was nice for resolution but, stylistically speaking, I wish Dickens had plotted out the novel in such a way that some of this could have been resolved as part of the narrative rather than as an epilogue. Sampson and Sally got their just desserts, but it was hard to read this little tidbit:

...when Mr. Brass was moving in a hackney coach towards the building where these wags assembled, saluted him with rotten eggs and carcasses of kittens..."

That's just wrong.

What's with the stake through Quilp's heart? Why? Is there a Biblical allusion here that I'm missing?

Sophronia Sphinx? That's a stripper name if I ever heard one! (Which, technically, I haven't, but one imagines...) One can't help being reminded of Sophronia Lammle from Our Mutual Friend, but we hope the Marchioness's marriage to Dick was happier than the Lammle's was. By the way... I'm pleased that Dick's aunt didn't bestow her entire fortune on Dick, but gave him only a modest stipend. Further, I'm very pleased that he was grateful for it, and not greedy.

My favorite part of this chapter was mentioned by Peter and concerned Whisker:

"...his last act (like a choleric old gentleman) was to kick his doctor."

I'll leave it there for now. My earlier tirade has exhausted me, and I must go have a soothing cup of tea and calm my nerves. Like the schoolmaster, I prefer a quiet life.

Mary Lou

The best things about the Curiosities are that we are candid, articulate, humourous, inquisitive and yet considerate of other members’ opinions. Added to that is all the sharing of links, videos, pictures, illustrations and esoteric bits and pieces.

How can you be a horrible person if you are all of the above? :-)

I am a huge fan of Nell. Still, I see your points and even (a bit grudgingly) agree with you to a degree. It will be fun as the next week unfolds.

Thank you for your kind words. It is great fun being a Moderator. And now a confession. BR and MC are my least favourite Dickens novels. I also will feel less comfortable writing commentaries for them. You will notice me limping through the next two novels.

The best things about the Curiosities are that we are candid, articulate, humourous, inquisitive and yet considerate of other members’ opinions. Added to that is all the sharing of links, videos, pictures, illustrations and esoteric bits and pieces.

How can you be a horrible person if you are all of the above? :-)

I am a huge fan of Nell. Still, I see your points and even (a bit grudgingly) agree with you to a degree. It will be fun as the next week unfolds.

Thank you for your kind words. It is great fun being a Moderator. And now a confession. BR and MC are my least favourite Dickens novels. I also will feel less comfortable writing commentaries for them. You will notice me limping through the next two novels.

I enjoyed this book a lot--the journey, the surrealism, and the characters along the way--but Nell's death disappointed me. Maybe because it defied my expectations. When Kit arrived, I thought Grandpa was moaning, because Nell was dying, not because she was already dead. It saddened me that Nell didn't get a chance to see Kit and her bird again; they were too late. At first, I thought Nell was sleeping, as Grandpa said she was. So, it came as a shock when the narrator said, rather starkly, "She was dead."

I enjoyed this book a lot--the journey, the surrealism, and the characters along the way--but Nell's death disappointed me. Maybe because it defied my expectations. When Kit arrived, I thought Grandpa was moaning, because Nell was dying, not because she was already dead. It saddened me that Nell didn't get a chance to see Kit and her bird again; they were too late. At first, I thought Nell was sleeping, as Grandpa said she was. So, it came as a shock when the narrator said, rather starkly, "She was dead."I guess I was expecting a traditional death scene with coughing, wheezing, and visions of angels, similar to Smike's death in NN. I didn't expect that Nell would die "offstage" and the narrator would give us a report of it.

I think Dickens had Nell die offstage to support the idea that she was perfect. She didn't die in a human way with suffering. We were told that she didn't suffer, had a smile on her face, and looked very good and refreshed.

Maybe this was an ascension, rather than a death? Hence the star in the sky and the imagery of Nell climbing the stairs in the church tower, as mentioned by the townspeople. My impression is that Nell died, not because she was sick and defective, but because she was angelic. Her spirit was released from her body, like Kit was released from jail. The townspeople associated her with angels.

I love Dick's transformation. His experiences shaped him into a good, responsible man. He also married a woman that he didn't expect, but who made him happy. We also learned the Marchioness's age. She spent six years in school and married Dick at age 19, which implies she was 13 before--same age as Little Nell. Could there be a connection between Dick's plan to marry Nell and the reality that unfolded--him marrying the Marchioness?

I love Dick's transformation. His experiences shaped him into a good, responsible man. He also married a woman that he didn't expect, but who made him happy. We also learned the Marchioness's age. She spent six years in school and married Dick at age 19, which implies she was 13 before--same age as Little Nell. Could there be a connection between Dick's plan to marry Nell and the reality that unfolded--him marrying the Marchioness?I also like that Quilp's wife inherited a fortune and married a kinder man, independent of her mother's influence. I never understood the wife's loyalty and concern for Quilp, and unlike Dick, we didn't see her transform her attitude and become an independent thinker. Either way, she deserved a better life, and I'm glad she got one.

Alissa wrote: "I enjoyed this book a lot--the journey, the surrealism, and the characters along the way--but Nell's death disappointed me. Maybe because it defied my expectations. When Kit arrived, I thought Gran..."

Hi Alissa

I had never thought about the fact that Nell dies offstage until I read your post. Your comments about why Dickens would do that rather than go for the more melodramatic scene makes total sense within the context of the novel. Funny how I often miss the obvious.

The phrase “she was dead” is certainly a stark end point, especially considering Nell’s lengthy decline.

As to the age of the Marchioness when she first was part of the story and then her marriage six years later there may well be a reason. My guess is that, like Nell at age 13, that age places them both one year in age before a female could marry. Thus, Dickens protects the innocence and purity of both Nell and the Marchioness within the structure of the early Victorian Age.

Hi Alissa

I had never thought about the fact that Nell dies offstage until I read your post. Your comments about why Dickens would do that rather than go for the more melodramatic scene makes total sense within the context of the novel. Funny how I often miss the obvious.

The phrase “she was dead” is certainly a stark end point, especially considering Nell’s lengthy decline.

As to the age of the Marchioness when she first was part of the story and then her marriage six years later there may well be a reason. My guess is that, like Nell at age 13, that age places them both one year in age before a female could marry. Thus, Dickens protects the innocence and purity of both Nell and the Marchioness within the structure of the early Victorian Age.

Ami wrote: "Peter, I didn't think Dickens gave me room for any other suggestion. He had me cornered, the solitary light and sparkling star coming at me deeply rooted in allegory.."

Ami wrote: "Peter, I didn't think Dickens gave me room for any other suggestion. He had me cornered, the solitary light and sparkling star coming at me deeply rooted in allegory.."Yes. Exactly. He definitely laid the way for that one.

Mary Lou wrote: "First, let me say, Peter, what a wise choice the other moderators made when they welcomed you to their ranks. You always give us something new to consider, and make the text deeper and more meaningful with your summaries and comments...."

Mary Lou wrote: "First, let me say, Peter, what a wise choice the other moderators made when they welcomed you to their ranks. You always give us something new to consider, and make the text deeper and more meaningful with your summaries and comments...."Yes! I couldn't get through this book the first time I read it. The balance of sweet-and-sour commentary from all the moderators gave me some alternative perspectives to read from and things to look for, and this time I was able to read through to the end. Thank you.

Mary Lou wrote: "What could be worse than the epic death of Little Nell?? The coddling of her selfish, horrible grandfather!..."

Mary Lou wrote: "What could be worse than the epic death of Little Nell?? The coddling of her selfish, horrible grandfather!..."Grandpa has me in a fury to the end. I don't think Nell was ever, ever a real, living, suffering person for him. When she was alive she was either the replacement for her dead mother or grandmother, or an excuse to gamble, or his servant and provider. He cares for her in death like he cared for her in life: with the utmost self-absorption, and the proof of this is his indifference to the people who go on living. His younger brother pleads for recognition and fellowship, and Nell's little friend does everything he can to draw grandfather back into life, but grandfather isn't interested in life. It might make some actual demands of him, or require the modicum of selflessness that he's incapable of delivering.

When I read this book, I realize that even though I love a good typological character (viewing despicable Quilp as a devil did help me appreciate his scenes more), I would rather have such characters retain some humanity. I admired Nell when she was bearing up so admirably under the terrible burdens her grandfather laid on her, but when she checked out of life and attained perfection, a perfection at odds with the efforts of the people who were doing what they could to carry on (Nell's fantasies at the end are all about death, no matter who tries to help her), I didn't want to spend time with her anymore.

Peter wrote: " In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they walked by the riverside earlier in her travels. This is a rather brief reference to the girls and perhaps Dickens needed to expand this somewhat. In last week’s comments there were comments about the young girls. What do you think? ..."

Peter wrote: " In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they walked by the riverside earlier in her travels. This is a rather brief reference to the girls and perhaps Dickens needed to expand this somewhat. In last week’s comments there were comments about the young girls. What do you think? ..."I think he meant to do something about the girls and then got distracted by Kit and Dick and the Brasses and decided he wouldn't come back to them after all, and dispatched them in less than a paragraph. Which honestly I would rather see happen than have him try to come up with a short plot-summary of whatever it was he originally planned to do with them, and toss it in without much development.

A friend and Dickens scholar told me once that Dickens was different from many writers because he was already being published as he learned to write, and I do think I'm seeing this as we read these early books. As somebody who writes and teaches (many kinds of) writing, I find it immensely inspiring to see how far the guy who wrote Great Expectations (which I have been reading with a class while I read Old Curiosity Shop here) had to come in his career. This feels like a very sloppy book, but also a book in which the author is learning how to put together a compelling supporting character or how to sketch flawed human nature, and there are what feel to me like throwaway scenes but I know they'll be very important in later books--the social unrest that Nell observes as she leaves London, for instance.

So it has been a rich experience reading, this, even if also an exasperating one--and so far an even richer experience to be working on this project of reading all the novels in their order of publication.

Also, three things I am happy about in this last set of chapters:

--Tom Scott. He feels very underdeveloped as a character, but there is this glorious defiance to him that he's allowed to retain all the way to the end.

--after a flirtation with calling him "the younger brother," Dickens brings back "the single gentleman" as his moniker.

--one more glimpse of Mrs. Jarley.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: " In her final hours she spoke of the two sisters she had watched as they walked by the riverside earlier in her travels. This is a rather brief reference to the girls and perhaps Dick..."

Hi Julie

I found your comment from a friend that Dickens “was already being published as he learned to write” very helpful as I continually try to figure out Dickens’s uniqueness.

Also, to be reading GE with a class while working through TOCS with us at the same time must have been both fascinating and challenging as you compared and considered them both in the light of the other.

Thanks for carrying the Dickens flag into the classroom.

Hi Julie

I found your comment from a friend that Dickens “was already being published as he learned to write” very helpful as I continually try to figure out Dickens’s uniqueness.

Also, to be reading GE with a class while working through TOCS with us at the same time must have been both fascinating and challenging as you compared and considered them both in the light of the other.

Thanks for carrying the Dickens flag into the classroom.

Julie wrote: "...grandfather isn't interested in life. It might make some actual demands of him..."

Julie wrote: "...grandfather isn't interested in life. It might make some actual demands of him..."Well put, Julie. Despite his miraculous reformation when it came to gambling, Grandfather's character was consistent to the end.

Yes, I have to admit, I think Dickens missed the mark with the Grandpa character. As a main character, Grandpa should have been sympathetic, but instead, he was just annoying. His repentance wasn't convincing either. A flawed, yet likeable, Grandpa would have helped me understand Nell better, because Nell loved him for a reason. We just didn't get a convincing reason why!

Yes, I have to admit, I think Dickens missed the mark with the Grandpa character. As a main character, Grandpa should have been sympathetic, but instead, he was just annoying. His repentance wasn't convincing either. A flawed, yet likeable, Grandpa would have helped me understand Nell better, because Nell loved him for a reason. We just didn't get a convincing reason why!

Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"

Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"I wondered this too. Maybe it has something to do with the river. The river is an important symbol. It appears in both Nell's and Quilp's deaths. The two girls and Nell form a trinity as well.

Peter wrote: "What was your response to the grandfather’s death?"

I expected it, because Nell and Grandpa are a unit who can't be separated. Them laying together means they're at peace now.

Peter wrote: "The price Dorian paid for his lifestyle was his death, and the death of other innocent people. Nell dies too, but whose legacy would one aspire to be in their own life, Nell’s or Dorian’s?"

I'm not familiar with Dorian, but I like your point about legacy and aspiring to be good. This is why I like Nell and Dickens's good characters. Dickens is showing us our potential, that it's possible to stay pure in a corrupt world and to carve out our own niche of happiness. Nell had a tragic life, but she still found her niche at the church, triumphed over evil, and died happy.

Dickens shows that goodness is a choice and we don't have to be like our enemies and succumb to our environment. I see the good characters as templates to reflect upon. Like, what makes a true lady/gentleman? What does integrity look like? How does one handle difficult people and situations with dignity? Dickens shows this through his good characters.

Alissa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"

I wondered this too. Maybe it has something to do with the river. The r..."

Hi Alissa

Thanks for the insights. The two girls being specifically mentioned is puzzling to me. At one level I thought it suggestive of how siblings could be. With Fred, Nell has no connection, no caring, and he certainly did not love Nell.

As a symbol, water often suggests life, eternity and death. Its movement and flow are central to and reflective of our own life’s path. The river as a symbol is an interesting angle. Dickens certainly relies on the presence of a river in many of his novels such as GE, OMF and, of course, TOCS. I found the chapter with Nell and grandfather’s passage with the bargemen that leads to the industrial city with the fire to be very symbolic and even bordering on myth. The death of Paul Dombey is also very clearly connected to water. The empty well in the church also has resonance with Nell’s fate. Water is a key to this novel.

Nell and her grandfather are both at peace now. You are right.

I would not have thought about Dorian Grey at all except I have just finished re-reading it. A bit of chance, I guess. I really liked your phrasing about how Dickens shows the reader a human’s potential. Humans have a choice and that we do not have to be like our enemies or succumb to our environment. I too see Dickens as using his good characters as models to learn from for our own lives.

Your comments remind me of the lines from John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” that tell us humans are “Sufficient to have stood though free to fall.”

I wondered this too. Maybe it has something to do with the river. The r..."

Hi Alissa

Thanks for the insights. The two girls being specifically mentioned is puzzling to me. At one level I thought it suggestive of how siblings could be. With Fred, Nell has no connection, no caring, and he certainly did not love Nell.

As a symbol, water often suggests life, eternity and death. Its movement and flow are central to and reflective of our own life’s path. The river as a symbol is an interesting angle. Dickens certainly relies on the presence of a river in many of his novels such as GE, OMF and, of course, TOCS. I found the chapter with Nell and grandfather’s passage with the bargemen that leads to the industrial city with the fire to be very symbolic and even bordering on myth. The death of Paul Dombey is also very clearly connected to water. The empty well in the church also has resonance with Nell’s fate. Water is a key to this novel.

Nell and her grandfather are both at peace now. You are right.

I would not have thought about Dorian Grey at all except I have just finished re-reading it. A bit of chance, I guess. I really liked your phrasing about how Dickens shows the reader a human’s potential. Humans have a choice and that we do not have to be like our enemies or succumb to our environment. I too see Dickens as using his good characters as models to learn from for our own lives.

Your comments remind me of the lines from John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” that tell us humans are “Sufficient to have stood though free to fall.”

Peter wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"

Peter wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"I wondered this too. Maybe it has something to do with t..."

Alissa wrote: "Peter wrote: "Why would Dickens specifically remind the reader about the two girls that Nell followed so many chapters ago?"

I wondered this too. Maybe it has something to do with the river. The r..."

I have a question...

God, the Father, in some cases can be seen as being cruel for the trials he knowingly put his son/Jesus through. He, the Father, of course had an ultimate plan for Jesus, building him up to be the savior of man for the greater good of mankind. While Grandfather Trent who was definitely not known for being omniscient or omnipotent, for what he allows Nell to endure in his name, isn’t there a stronger parallel between God/Father and Jesus, and Grandfather and Nell... wouldn’t it be Grandfather, Grandaughter and the Holy Spirit, who make up the Holy Trinity?

Is this a stretch?

Hi Ami

I’m hesitant to see the parallels to the extent you suggest. Having said that, I will sit on the fence a bit. I think there is a clear and definite thread of the New Testament that runs through his novels, and his private publication The Life of Our Lord points to his general belief.

Dickens championed the poor and downtrodden, and had very little tolerance or time for preachers in his novels. I have never come to a comfortable decision on Dickens’s position. That said, I do think that Dickens constantly drew upon biblical allusions to give his novels a resonance and relativity to his readers.

I’m hesitant to see the parallels to the extent you suggest. Having said that, I will sit on the fence a bit. I think there is a clear and definite thread of the New Testament that runs through his novels, and his private publication The Life of Our Lord points to his general belief.

Dickens championed the poor and downtrodden, and had very little tolerance or time for preachers in his novels. I have never come to a comfortable decision on Dickens’s position. That said, I do think that Dickens constantly drew upon biblical allusions to give his novels a resonance and relativity to his readers.

Peter wrote: "Hi Ami

Peter wrote: "Hi AmiI’m hesitant to see the parallels to the extent you suggest. Having said that, I will sit on the fence a bit. I think there is a clear and definite thread of the New Testament that runs thr..."

Then let’s not think about it anymore. I trust your judgement on Dickens’s influences and motivations a lot more than I do me thinking about parallels between Characters in the Bible and this novel. :)

Julie wrote: "Is it haiku time yet, or is that next week?"

Julie

Let’s launch into the haiku postings beginning Sunday. I cannot wait to read the submissions.

Should we extend our poetic comments to limericks as well?

Julie

Let’s launch into the haiku postings beginning Sunday. I cannot wait to read the submissions.

Should we extend our poetic comments to limericks as well?

Julie wrote: "Is it haiku time yet, or is that next week?"

As Peter said, it's best to do that next week, and maybe to throw in a limerick :-) I hope the Muse will stop at my place and give me some idea, but at the moment I am lagging behind discussions anyway because it's exam time in Germany ...

I have enjoyed reading this thread and must express my warmest thanks and admiration to Peter for doing the recaps so nicely and with so much care. About the death scene as such, I must say that I agree with you, Mary Lou, although I must also confess the following:

When reading about Little Nell's death and witnessing her interactions with her grandfather and the grandfather's remorse and all that, a little thing inside myself died, too, and it was probably one of the best things I had in me, viz. my Patience ;-)

One might also add, on a more cynical note, that Little Nell not only did her dying off-stage, but much of her living, too ...

And this is also why she is not convincing to me as a lesson of how to remain a "good" person and to choose the right path when confronted with evil and with difficulty. The reason being that Little Nell is so good and perfect and forbearing that not for a minute does her patience with Grampa wane, not for a second does she consider leaving him to his own devices, or even find herself thinking, or being thought to, about what a relief it must be for her without him. She never wavers, never doubts but always sees the right path in front of her, and she most determinedly, but gently, of course, presses her grandfather on to follow her down, or up, that path.

As a reader, I think I could learn more from a character who also experiences feelings of doubt, of undecisiveness, who even has his moments of baseness and weakness. In the first place, such a character is by far more interesting - esp. psychologically - for me as a reader. Just think of Dostoyevsky's characers and their ups and downs, for instance. And secondly, since I myself am definitely not as perfect as Little Nell, there is little she can teach me because she is obviously not faced with the same problems as I or she meets them from a different starting point. When all is said and done, Little Nell is without any real human essence to me - human in the sense of being subject to passions, fears and bouts of egoism as well.

As Peter said, it's best to do that next week, and maybe to throw in a limerick :-) I hope the Muse will stop at my place and give me some idea, but at the moment I am lagging behind discussions anyway because it's exam time in Germany ...

I have enjoyed reading this thread and must express my warmest thanks and admiration to Peter for doing the recaps so nicely and with so much care. About the death scene as such, I must say that I agree with you, Mary Lou, although I must also confess the following:

When reading about Little Nell's death and witnessing her interactions with her grandfather and the grandfather's remorse and all that, a little thing inside myself died, too, and it was probably one of the best things I had in me, viz. my Patience ;-)

One might also add, on a more cynical note, that Little Nell not only did her dying off-stage, but much of her living, too ...

And this is also why she is not convincing to me as a lesson of how to remain a "good" person and to choose the right path when confronted with evil and with difficulty. The reason being that Little Nell is so good and perfect and forbearing that not for a minute does her patience with Grampa wane, not for a second does she consider leaving him to his own devices, or even find herself thinking, or being thought to, about what a relief it must be for her without him. She never wavers, never doubts but always sees the right path in front of her, and she most determinedly, but gently, of course, presses her grandfather on to follow her down, or up, that path.

As a reader, I think I could learn more from a character who also experiences feelings of doubt, of undecisiveness, who even has his moments of baseness and weakness. In the first place, such a character is by far more interesting - esp. psychologically - for me as a reader. Just think of Dostoyevsky's characers and their ups and downs, for instance. And secondly, since I myself am definitely not as perfect as Little Nell, there is little she can teach me because she is obviously not faced with the same problems as I or she meets them from a different starting point. When all is said and done, Little Nell is without any real human essence to me - human in the sense of being subject to passions, fears and bouts of egoism as well.

Mary Lou

Thank you for the link. It is impressive and a good likeness. Great story about the statue’s travels before finally finding a home as well.

So ... we have Little Nell depicted on many postage stamps and Little Nell the only character to be accompany the Dickens statue. Hmmm. What might this mean? :-)

Thank you for the link. It is impressive and a good likeness. Great story about the statue’s travels before finally finding a home as well.

So ... we have Little Nell depicted on many postage stamps and Little Nell the only character to be accompany the Dickens statue. Hmmm. What might this mean? :-)

A nice article, Mary Lou. It speaks volumes about Dickens‘s self-confidence that he did not want any statues of him to be erected, doesn‘t it? Maybe, he knew well enough that his books would be the best guarantee of living on in the minds of people.

As to why Little Nell was the only character to accompany the stone Dickens, maybe they just ran out of stone? That‘s the only possible explanation to me :-)

As to why Little Nell was the only character to accompany the stone Dickens, maybe they just ran out of stone? That‘s the only possible explanation to me :-)

Hello all, I walked in the door this evening, opened the computer, hit the start button, the lights actually came on and here I am. For now anyway. Maybe, just maybe this second new charger will do the trick and my computer will no longer do extremely odd things before just shutting down altogether. But for now I am here and I am ready to defend poor Little Nell, I brought lots of help with me too. Here we go:

The death of Little Nell. The writer Thomas Carlyle was overcome with grief at the news. Actor William Macready noted in his diary: "I have never read printed words that gave me so much pain." Lord Jeffrey, a literary critic and friend of Dickens, was found in tears after reading her death scene. Even Daniel O'Connell was traumatized. Learning of the event while travelling by train, the Liberator burst into tears, declared "he should not have killed her", and threw his book out the window.

When a ship arrived in New York carrying copies of the final chapters, crowds waiting on the pier shouted to those on board: "Is Little Nell dead?" But the captain of the packet had read the ending already, and when he came up on deck the crowd saw the tears streaming down his face and that told them the terrible truth they were expecting but hoped wouldn't be so.

Little Nell was dead.

There were cries of anguish from the crowd, wails of lamentation, and howls of anger and outrage.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

Fast shortening as the life of little Nell was now, the dying year might have seen it pass away; but I never knew him wind up any tale with such a sorrowful reluctance as this. He caught at any excuse to hold his hand from it, and stretched to the utmost limit the time left to complete it in. Christmas interposed its delays too, so that Twelfth-night had come and gone when I wrote to him in the belief that he was nearly done. "Done!" he wrote back to me on Friday, the 7th;

"Done!!! Why, bless you, I shall not be done till Wednesday night. I only began yesterday, and this part of the story is not to be galloped over, I can tell you. I think it will come famously—but I am the wretchedest of the wretched. It casts the most horrible shadow upon me, and it is as much as I can do to keep moving at all. I tremble to approach the place a great deal more than Kit; a great deal more than Mr. Garland; a great deal more than the Single Gentleman. I sha'n't recover it for a long time. Nobody will miss her like I shall. It is such a very painful thing to me, that I really cannot express my sorrow. Old wounds bleed afresh when I only think of the way of doing it: what the actual doing it will be, God knows. I can't preach to myself the schoolmaster's consolation, though I try. Dear Mary died yesterday, when I think of this sad story. I don't know what to say about dining to-morrow—perhaps you'll send up to-morrow morning for news? That'll be the best way. I have refused several invitations for this week and next, determining to go nowhere till I had done. I am afraid of disturbing the state I have been trying to get into, and having to fetch it all back again."

He had finished, all but the last chapter, on the Wednesday named; that was the 12th of January; and on the following night he read to me the two chapters of Nell's death, the seventy-first and seventy-second, with the result described in a letter to me of the following Monday, the 17th January, 1841:

"I can't help letting you know how much your yesterday's letter pleased me. I felt sure you liked the chapters when we read them on Thursday night, but it was a great delight to have my impression so strongly and heartily confirmed. You know how little value I should set on what I had done, if all the world cried out that it was good, and those whose good opinion and approbation I value most were silent. The assurance that this little closing of the scene touches and is felt by you so strongly, is better to me than a thousand most sweet voices out of doors. When I first began, on your valued suggestion, to keep my thoughts upon this ending of the tale, I resolved to try and do something which might be read by people about whom Death had been, with a softened feeling, and with consolation. . . . After you left last night, I took my desk up-stairs, and, writing until four o'clock this morning, finished the old story. It makes me very melancholy to think that all these people are lost to me forever, and I feel as if I never could become attached to any new set of characters."

The words printed in italics, as underlined by himself, give me my share in the story which had gone so closely to his heart. I was responsible for its tragic ending. He had not thought of killing her, when, about half-way through, I asked him to consider whether it did not necessarily belong even to his own conception, after taking so mere a child through such a tragedy of sorrow, to lift her also out of the commonplace of ordinary happy endings so that the gentle pure little figure and form should never change to the fancy. All that I meant he seized at once, and never turned aside from it again.......

....But the main idea and chief figure of the piece constitute its interest for most people, and give it rank upon the whole with the most attractive productions of English fiction. I am not acquainted with any story in the language more adapted to strengthen in the heart what most needs help and encouragement, to sustain kindly and innocent impulses, and to awaken everywhere the sleeping germs of good. It includes necessarily much pain, much uninterrupted sadness; and yet the brightness and sunshine quite overtop the gloom. The humor is so benevolent; the view of errors that have no depravity of heart in them is so indulgent; the quiet courage under calamity, the purity that nothing impure can soil, are so full of tender teaching. Its effect as a mere piece of art, too, considering the circumstances in which I have shown it to be written, I think very noteworthy. It began with a plan for but a short half-dozen chapters; it grew into a full-proportioned story under the warmth of the feeling it had inspired its writer with; its very incidents created a necessity at first not seen; and it was carried to a close only contemplated after a full half of it had been written. Yet, from the opening of the tale to that undesigned ending,—from the image of little Nell asleep amid the quaint grotesque figures of the old curiosity warehouse to that other final sleep she takes among the grim forms and carvings of the old church aisle,—the main purpose seems to be always present. The characters and incidents that at first appear most foreign to it are found to have had with it a close relation. The hideous lumber and rottenness that surround the child in her grandfather's home take shape again in Quilp and his filthy gang. In the first still picture of Nell's innocence in the midst of strange and alien forms, we have the forecast of her after-wanderings, her patient miseries, her sad maturity of experience before its time. Without the show-people and their blended fictions and realities, their wax-works, dwarfs, giants, and performing dogs, the picture would have wanted some part of its significance. Nor could the genius of Hogarth himself have given it higher expression than in the scenes by the cottage door, the furnace-fire, and the burial-place of the old church, over whose tombs and gravestones hang the puppets of Mr. Punch's show while the exhibitors are mending and repairing them. And when, at last, Nell sits within the quiet old church where all her wanderings end, and gazes on those silent monumental groups of warriors,—helmets, swords, and gauntlets wasting away around them,—the associations among which her life had opened seem to have come crowding on the scene again, to be present at its close,—but stripped of their strangeness; deepened into solemn shapes by the suffering she has undergone; gently fusing every feeling of a life past into hopeful and familiar anticipation of a life to come; and already imperceptibly lifting her, without grief or pain, from the earth she loves, yet whose grosser paths her light steps only touched to show the track through them to heaven. This is genuine art, and such as all cannot fail to recognize who read the book in a right sympathy with the conception that pervades it. Nor, great as the discomfort was of reading it in brief weekly snatches, can I be wholly certain that the discomfort of so writing it involved nothing but disadvantage. With so much in every portion to do, and so little space to do it in, the opportunities to a writer for mere self-indulgence were necessarily rare.