The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Barnaby Rudge

>

BR Chapters 61-65

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

In Chapter 62 we find ourselves in jail with Old Rudge and unfortunately with Barnaby also. It is most unfortunate for Old Rudge because he is not aware Barnaby is there and so the plan the blind man comes up with won't work. For we're told that after a long while the blind man enters his cell. There is a rather long and strange - at least I thought so - conversation of how and why Rudge finds himself where he is. According to him he couldn't help it. He says he went to Haredale's home to avoid him, which makes little sense to me, then says he was chased and driven there, both by Haredale and by Fate. OK. He goes on to say that for twenty eight years the murdered man has been chasing him.

‘Eight-and-twenty years! Eight-and-twenty years! He has never changed in all that time, never grown older, nor altered in the least degree. He has been before me in the dark night, and the broad sunny day; in the twilight, the moonlight, the sunlight, the light of fire, and lamp, and candle; and in the deepest gloom. Always the same! In company, in solitude, on land, on shipboard; sometimes leaving me alone for months, and sometimes always with me. I have seen him, at sea, come gliding in the dead of night along the bright reflection of the moon in the calm water; and I have seen him, on quays and market-places, with his hand uplifted, towering, the centre of a busy crowd, unconscious of the terrible form that had its silent stand among them. Fancy! Are you real? Am I? Are these iron fetters, riveted on me by the smith’s hammer, or are they fancies I can shatter at a blow?’

I almost believe that Rudge has been driven mad by what he had done. He kills his friend and employer, he kills the gardener who saw what he did, he switched their clothes, he left his wife and the country, and has seen the man he murdered ever since that night. I'm not sure why he doesn't see both men. Finally with more of how the murdered man has always been there, how he has been forced to come back over and over, we finally get to the plan Stagg has come up with which won't work.

‘—You are impatient,’ said the blind man, calmly; ‘it’s a good sign, and looks like life—that your son Barnaby had been lured away from her by one of his companions who knew him of old, at Chigwell; and that he is now among the rioters.’

‘And what is that to me? If father and son be hanged together, what comfort shall I find in that?’

‘Stay—stay, my friend,’ returned the blind man, with a cunning look, ‘you travel fast to journeys’ ends. Suppose I track my lady out, and say thus much: “You want your son, ma’am—good. I, knowing those who tempt him to remain among them, can restore him to you, ma’am—good. You must pay a price, ma’am, for his restoration—good again. The price is small, and easy to be paid—dear ma’am, that’s best of all.”’

‘What mockery is this?’

‘Very likely, she may reply in those words. “No mockery at all,” I answer: “Madam, a person said to be your husband (identity is difficult of proof after the lapse of many years) is in prison, his life in peril—the charge against him, murder. Now, ma’am, your husband has been dead a long, long time. The gentleman never can be confounded with him, if you will have the goodness to say a few words, on oath, as to when he died, and how; and that this person (who I am told resembles him in some degree) is no more he than I am. Such testimony will set the question quite at rest. Pledge yourself to me to give it, ma’ am, and I will undertake to keep your son (a fine lad) out of harm’s way until you have done this trifling service, when he shall be delivered up to you, safe and sound. On the other hand, if you decline to do so, I fear he will be betrayed, and handed over to the law, which will assuredly sentence him to suffer death. It is, in fact, a choice between his life and death. If you refuse, he swings. If you comply, the timber is not grown, nor the hemp sown, that shall do him any harm.”’

‘There is a gleam of hope in this!’ cried the prisoner.

‘A gleam!’ returned his friend, ‘a noon-blaze; a full and glorious daylight. Hush! I hear the tread of distant feet. Rely on me.’

‘When shall I hear more?’

‘As soon as I do. I should hope, to-morrow. They are coming to say that our time for talk is over. I hear the jingling of the keys. Not another word of this just now, or they may overhear us.’

And now Stagg leaves to get the plan in motion, and Rudge is left behind full of hope, until he takes a walk in the prison yard and finds himself face to face with Barnaby. He finally tells Barnaby that he is his father which delights our poor Barnaby.

They stood face to face, staring at each other. He shrinking and cowed, despite himself; Barnaby struggling with his imperfect memory, and wondering where he had seen that face before. He was not uncertain long, for suddenly he laid hands upon him, and striving to bear him to the ground, cried:

‘Ah! I know! You are the robber!’

He said nothing in reply at first, but held down his head, and struggled with him silently. Finding the younger man too strong for him, he raised his face, looked close into his eyes, and said,

‘I am your father.’

God knows what magic the name had for his ears; but Barnaby released his hold, fell back, and looked at him aghast. Suddenly he sprung towards him, put his arms about his neck, and pressed his head against his cheek.

Yes, yes, he was; he was sure he was. But where had he been so long, and why had he left his mother by herself, or worse than by herself, with her poor foolish boy? And had she really been as happy as they said? And where was she? Was she near there? She was not happy now, and he in jail? Ah, no.

Not a word was said in answer; but Grip croaked loudly, and hopped about them, round and round, as if enclosing them in a magic circle, and invoking all the powers of mischief.

By the way, does anyone remember what happened to the money he stole? Or didn't he steal any at all, I can't remember.

‘Eight-and-twenty years! Eight-and-twenty years! He has never changed in all that time, never grown older, nor altered in the least degree. He has been before me in the dark night, and the broad sunny day; in the twilight, the moonlight, the sunlight, the light of fire, and lamp, and candle; and in the deepest gloom. Always the same! In company, in solitude, on land, on shipboard; sometimes leaving me alone for months, and sometimes always with me. I have seen him, at sea, come gliding in the dead of night along the bright reflection of the moon in the calm water; and I have seen him, on quays and market-places, with his hand uplifted, towering, the centre of a busy crowd, unconscious of the terrible form that had its silent stand among them. Fancy! Are you real? Am I? Are these iron fetters, riveted on me by the smith’s hammer, or are they fancies I can shatter at a blow?’

I almost believe that Rudge has been driven mad by what he had done. He kills his friend and employer, he kills the gardener who saw what he did, he switched their clothes, he left his wife and the country, and has seen the man he murdered ever since that night. I'm not sure why he doesn't see both men. Finally with more of how the murdered man has always been there, how he has been forced to come back over and over, we finally get to the plan Stagg has come up with which won't work.

‘—You are impatient,’ said the blind man, calmly; ‘it’s a good sign, and looks like life—that your son Barnaby had been lured away from her by one of his companions who knew him of old, at Chigwell; and that he is now among the rioters.’

‘And what is that to me? If father and son be hanged together, what comfort shall I find in that?’

‘Stay—stay, my friend,’ returned the blind man, with a cunning look, ‘you travel fast to journeys’ ends. Suppose I track my lady out, and say thus much: “You want your son, ma’am—good. I, knowing those who tempt him to remain among them, can restore him to you, ma’am—good. You must pay a price, ma’am, for his restoration—good again. The price is small, and easy to be paid—dear ma’am, that’s best of all.”’

‘What mockery is this?’

‘Very likely, she may reply in those words. “No mockery at all,” I answer: “Madam, a person said to be your husband (identity is difficult of proof after the lapse of many years) is in prison, his life in peril—the charge against him, murder. Now, ma’am, your husband has been dead a long, long time. The gentleman never can be confounded with him, if you will have the goodness to say a few words, on oath, as to when he died, and how; and that this person (who I am told resembles him in some degree) is no more he than I am. Such testimony will set the question quite at rest. Pledge yourself to me to give it, ma’ am, and I will undertake to keep your son (a fine lad) out of harm’s way until you have done this trifling service, when he shall be delivered up to you, safe and sound. On the other hand, if you decline to do so, I fear he will be betrayed, and handed over to the law, which will assuredly sentence him to suffer death. It is, in fact, a choice between his life and death. If you refuse, he swings. If you comply, the timber is not grown, nor the hemp sown, that shall do him any harm.”’

‘There is a gleam of hope in this!’ cried the prisoner.

‘A gleam!’ returned his friend, ‘a noon-blaze; a full and glorious daylight. Hush! I hear the tread of distant feet. Rely on me.’

‘When shall I hear more?’

‘As soon as I do. I should hope, to-morrow. They are coming to say that our time for talk is over. I hear the jingling of the keys. Not another word of this just now, or they may overhear us.’

And now Stagg leaves to get the plan in motion, and Rudge is left behind full of hope, until he takes a walk in the prison yard and finds himself face to face with Barnaby. He finally tells Barnaby that he is his father which delights our poor Barnaby.

They stood face to face, staring at each other. He shrinking and cowed, despite himself; Barnaby struggling with his imperfect memory, and wondering where he had seen that face before. He was not uncertain long, for suddenly he laid hands upon him, and striving to bear him to the ground, cried:

‘Ah! I know! You are the robber!’

He said nothing in reply at first, but held down his head, and struggled with him silently. Finding the younger man too strong for him, he raised his face, looked close into his eyes, and said,

‘I am your father.’

God knows what magic the name had for his ears; but Barnaby released his hold, fell back, and looked at him aghast. Suddenly he sprung towards him, put his arms about his neck, and pressed his head against his cheek.

Yes, yes, he was; he was sure he was. But where had he been so long, and why had he left his mother by herself, or worse than by herself, with her poor foolish boy? And had she really been as happy as they said? And where was she? Was she near there? She was not happy now, and he in jail? Ah, no.

Not a word was said in answer; but Grip croaked loudly, and hopped about them, round and round, as if enclosing them in a magic circle, and invoking all the powers of mischief.

By the way, does anyone remember what happened to the money he stole? Or didn't he steal any at all, I can't remember.

In Chapter 63 I realized something you cannot tell my husband, I am in love with Gabriel Varden. I could just go on putting in one Gabriel comment after another and call the chapter good, so I think I will. First we find the mob on their way to break all the prisoners there are in London out of all the jails in London, but the first is where Barnaby is, and to get into that they need Gabriel to open the lock since he is the one who made it. But he certainly doesn't give in easily, his first words to them are:

‘What now, you villains!’ he demanded. ‘Where is my daughter?’

‘Ask no questions of us, old man,’ retorted Hugh, waving his comrades to be silent, ‘but come down, and bring the tools of your trade. We want you.’

‘Want me!’ cried the locksmith, glancing at the regimental dress he wore: ‘Ay, and if some that I could name possessed the hearts of mice, ye should have had me long ago. Mark me, my lad—and you about him do the same. There are a score among ye whom I see now and know, who are dead men from this hour. Begone! and rob an undertaker’s while you can! You’ll want some coffins before long.’

Unfortunately, when Gabriel threatens to shoot whoever it is that tries to get into his home, that ever annoying Miggs makes it clear that she has made the gun unoperable by pouring a mug of table-beer down the barrel. I have no idea what a mug of table-beer down a barrel of a gun would do, but apparently the gun doesn't work after it happens, so the rioters make it into the house, and once inside make their demands of Gabriel but he still refuses:

They were very wrathful with him (for he had wounded two men), and even called out to those in front, to bring him forth and hang him on a lamp-post. But Gabriel was quite undaunted, and looked from Hugh and Dennis, who held him by either arm, to Simon Tappertit, who confronted him.

‘You have robbed me of my daughter,’ said the locksmith, ‘who is far dearer to me than my life; and you may take my life, if you will. I bless God that I have been enabled to keep my wife free of this scene; and that He has made me a man who will not ask mercy at such hands as yours.

Then out of all the people there who seem now to be calling for him to be hung and Dennis delighted by it, the one person who tries to help him is our one and only Hugh, at least that's how it seems to me:

‘Don’t be a fool, master,’ whispered Hugh, seizing Varden roughly by the shoulder; ‘but do as you’re bid. You’ll soon hear what you’re wanted for. Do it!’

‘I’ll do nothing at your request, or that of any scoundrel here,’ returned the locksmith. ‘If you want any service from me, you may spare yourselves the pains of telling me what it is. I tell you, beforehand, I’ll do nothing for you.’

We're told Dennis is so affected by this that he has tears in his eyes and pleads for their prisoner to be hung like he wants to be. Hugh now reminds them that they need the locksmith and tells Sim to tell him what it is. This is my favorite part of the chapter:

‘So, tell him what we want,’ he said to Simon Tappertit, ‘and quickly. And open your ears, master, if you would ever use them after to-night.’

Gabriel folded his arms, which were now at liberty, and eyed his old ‘prentice in silence.

‘Lookye, Varden,’ said Sim, ‘we’re bound for Newgate.’

‘I know you are,’ returned the locksmith. ‘You never said a truer word than that.’

Miggs is finally let out of the room she had been locked in and Sim has her carried off to the place they are keeping Dolly and Emma in. The chapter ends this way:

They who were in the house poured out into the street; the locksmith was taken to the head of the crowd, and required to walk between his two conductors; the whole body was put in rapid motion; and without any shouts or noise they bore down straight on Newgate, and halted in a dense mass before the prison-gate.

‘What now, you villains!’ he demanded. ‘Where is my daughter?’

‘Ask no questions of us, old man,’ retorted Hugh, waving his comrades to be silent, ‘but come down, and bring the tools of your trade. We want you.’

‘Want me!’ cried the locksmith, glancing at the regimental dress he wore: ‘Ay, and if some that I could name possessed the hearts of mice, ye should have had me long ago. Mark me, my lad—and you about him do the same. There are a score among ye whom I see now and know, who are dead men from this hour. Begone! and rob an undertaker’s while you can! You’ll want some coffins before long.’

Unfortunately, when Gabriel threatens to shoot whoever it is that tries to get into his home, that ever annoying Miggs makes it clear that she has made the gun unoperable by pouring a mug of table-beer down the barrel. I have no idea what a mug of table-beer down a barrel of a gun would do, but apparently the gun doesn't work after it happens, so the rioters make it into the house, and once inside make their demands of Gabriel but he still refuses:

They were very wrathful with him (for he had wounded two men), and even called out to those in front, to bring him forth and hang him on a lamp-post. But Gabriel was quite undaunted, and looked from Hugh and Dennis, who held him by either arm, to Simon Tappertit, who confronted him.

‘You have robbed me of my daughter,’ said the locksmith, ‘who is far dearer to me than my life; and you may take my life, if you will. I bless God that I have been enabled to keep my wife free of this scene; and that He has made me a man who will not ask mercy at such hands as yours.

Then out of all the people there who seem now to be calling for him to be hung and Dennis delighted by it, the one person who tries to help him is our one and only Hugh, at least that's how it seems to me:

‘Don’t be a fool, master,’ whispered Hugh, seizing Varden roughly by the shoulder; ‘but do as you’re bid. You’ll soon hear what you’re wanted for. Do it!’

‘I’ll do nothing at your request, or that of any scoundrel here,’ returned the locksmith. ‘If you want any service from me, you may spare yourselves the pains of telling me what it is. I tell you, beforehand, I’ll do nothing for you.’

We're told Dennis is so affected by this that he has tears in his eyes and pleads for their prisoner to be hung like he wants to be. Hugh now reminds them that they need the locksmith and tells Sim to tell him what it is. This is my favorite part of the chapter:

‘So, tell him what we want,’ he said to Simon Tappertit, ‘and quickly. And open your ears, master, if you would ever use them after to-night.’

Gabriel folded his arms, which were now at liberty, and eyed his old ‘prentice in silence.

‘Lookye, Varden,’ said Sim, ‘we’re bound for Newgate.’

‘I know you are,’ returned the locksmith. ‘You never said a truer word than that.’

Miggs is finally let out of the room she had been locked in and Sim has her carried off to the place they are keeping Dolly and Emma in. The chapter ends this way:

They who were in the house poured out into the street; the locksmith was taken to the head of the crowd, and required to walk between his two conductors; the whole body was put in rapid motion; and without any shouts or noise they bore down straight on Newgate, and halted in a dense mass before the prison-gate.

After the fun I had with Gabriel Varden in the last chapter I find him in the next in much more danger as he continues his refusal to help the rioters to the end. The mob, always led by Hugh and Dennis, arrive at the gates of the jail and yell for the head jailer, Mr. Akerman, another man who refuses to do what they want, a man such as Garbriel Varden and Sir John Fielding. Mr. Akerman refuses and is turning away when Gabriel calls out to him:

‘Mr Akerman,’ cried Gabriel, ‘Mr Akerman.’

‘I will hear no more from any of you,’ replied the governor, turning towards the speaker, and waving his hand.

‘But I am not one of them,’ said Gabriel. ‘I am an honest man, Mr Akerman; a respectable tradesman—Gabriel Varden, the locksmith. You know me?’

‘You among the crowd!’ cried the governor in an altered voice.

‘Brought here by force—brought here to pick the lock of the great door for them,’ rejoined the locksmith. ‘Bear witness for me, Mr Akerman, that I refuse to do it; and that I will not do it, come what may of my refusal. If any violence is done to me, please to remember this.’

‘Is there no way of helping you?’ said the governor.

‘None, Mr Akerman. You’ll do your duty, and I’ll do mine. Once again, you robbers and cut-throats,’ said the locksmith, turning round upon them, ‘I refuse. Ah! Howl till you’re hoarse. I refuse.’

If Hugh doesn't do something to save Mr. Varden I'll never have anything to do with him again. But he doesn't help him and now with blows, offers of reward and threats of death, he still refuses. We're told the basket of tools was laid before him, but he cries out that he will not do it. Then there is this:

He had never loved his life so well as then, but nothing could move him. The savage faces that glared upon him, look where he would; the cries of those who thirsted, like wild animals, for his blood; the sight of men pressing forward, and trampling down their fellows, as they strove to reach him, and struck at him above the heads of other men, with axes and with iron bars; all failed to daunt him. He looked from man to man, and face to face, and still, with quickened breath and lessening colour, cried firmly, ‘I will not!’

Now there is no hope for my locksmith for Dennis knocks him to the ground. He rises but is knocked down again, over and over until:

He was down again, and up, and down once more, and buffeting with a score of them, who bandied him from hand to hand, when one tall fellow, fresh from a slaughter-house, whose dress and great thigh-boots smoked hot with grease and blood, raised a pole-axe, and swearing a horrible oath, aimed it at the old man’s uncovered head. At that instant, and in the very act, he fell himself, as if struck by lightning, and over his body a one-armed man came darting to the locksmith’s side. Another man was with him, and both caught the locksmith roughly in their grasp.

‘Leave him to us!’ they cried to Hugh—struggling, as they spoke, to force a passage backward through the crowd. ‘Leave him to us. Why do you waste your whole strength on such as he, when a couple of men can finish him in as many minutes! You lose time. Remember the prisoners! remember Barnaby!’

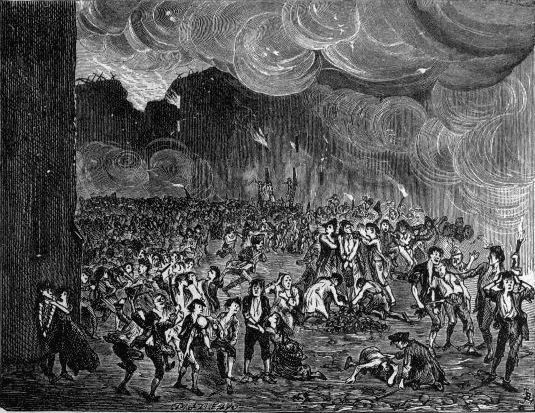

Hmm, we may have to keep those two in mind, especially that one armed man. Now the rioters must gain entrance to the prison by themselves which they do by burning the door which takes them quite a while and burns up lots of furniture. But now they are inside and the prisoners are about to be free once again, if they don't burn up first:

The door sank down again: it settled deeper in the cinders—tottered—yielded—was down!

As they shouted again, they fell back, for a moment, and left a clear space about the fire that lay between them and the jail entry. Hugh leapt upon the blazing heap, and scattering a train of sparks into the air, and making the dark lobby glitter with those that hung upon his dress, dashed into the jail.

The hangman followed. And then so many rushed upon their track, that the fire got trodden down and thinly strewn about the street; but there was no need of it now, for, inside and out, the prison was in flames.

‘Mr Akerman,’ cried Gabriel, ‘Mr Akerman.’

‘I will hear no more from any of you,’ replied the governor, turning towards the speaker, and waving his hand.

‘But I am not one of them,’ said Gabriel. ‘I am an honest man, Mr Akerman; a respectable tradesman—Gabriel Varden, the locksmith. You know me?’

‘You among the crowd!’ cried the governor in an altered voice.

‘Brought here by force—brought here to pick the lock of the great door for them,’ rejoined the locksmith. ‘Bear witness for me, Mr Akerman, that I refuse to do it; and that I will not do it, come what may of my refusal. If any violence is done to me, please to remember this.’

‘Is there no way of helping you?’ said the governor.

‘None, Mr Akerman. You’ll do your duty, and I’ll do mine. Once again, you robbers and cut-throats,’ said the locksmith, turning round upon them, ‘I refuse. Ah! Howl till you’re hoarse. I refuse.’

If Hugh doesn't do something to save Mr. Varden I'll never have anything to do with him again. But he doesn't help him and now with blows, offers of reward and threats of death, he still refuses. We're told the basket of tools was laid before him, but he cries out that he will not do it. Then there is this:

He had never loved his life so well as then, but nothing could move him. The savage faces that glared upon him, look where he would; the cries of those who thirsted, like wild animals, for his blood; the sight of men pressing forward, and trampling down their fellows, as they strove to reach him, and struck at him above the heads of other men, with axes and with iron bars; all failed to daunt him. He looked from man to man, and face to face, and still, with quickened breath and lessening colour, cried firmly, ‘I will not!’

Now there is no hope for my locksmith for Dennis knocks him to the ground. He rises but is knocked down again, over and over until:

He was down again, and up, and down once more, and buffeting with a score of them, who bandied him from hand to hand, when one tall fellow, fresh from a slaughter-house, whose dress and great thigh-boots smoked hot with grease and blood, raised a pole-axe, and swearing a horrible oath, aimed it at the old man’s uncovered head. At that instant, and in the very act, he fell himself, as if struck by lightning, and over his body a one-armed man came darting to the locksmith’s side. Another man was with him, and both caught the locksmith roughly in their grasp.

‘Leave him to us!’ they cried to Hugh—struggling, as they spoke, to force a passage backward through the crowd. ‘Leave him to us. Why do you waste your whole strength on such as he, when a couple of men can finish him in as many minutes! You lose time. Remember the prisoners! remember Barnaby!’

Hmm, we may have to keep those two in mind, especially that one armed man. Now the rioters must gain entrance to the prison by themselves which they do by burning the door which takes them quite a while and burns up lots of furniture. But now they are inside and the prisoners are about to be free once again, if they don't burn up first:

The door sank down again: it settled deeper in the cinders—tottered—yielded—was down!

As they shouted again, they fell back, for a moment, and left a clear space about the fire that lay between them and the jail entry. Hugh leapt upon the blazing heap, and scattering a train of sparks into the air, and making the dark lobby glitter with those that hung upon his dress, dashed into the jail.

The hangman followed. And then so many rushed upon their track, that the fire got trodden down and thinly strewn about the street; but there was no need of it now, for, inside and out, the prison was in flames.

In Chapter 65 we find the prisoners are given their freedom, whether they wanted it or not:

Anon some famished wretch whose theft had been a loaf of bread, or scrap of butcher’s meat, came skulking past, barefooted—going slowly away because that jail, his house, was burning; not because he had any other, or had friends to meet, or old haunts to revisit, or any liberty to gain, but liberty to starve and die.

Old Rudge hears the noise, sees the fire, sees the rioters, and is convinced they are coming to kill him having heard of his monstrous act. That there are men there that have probably committed the same monstrous acts doesn't seem to occur to him and he remains hidden as best he can in the dark corner of his cell. But they eventually enter his cell and instead of killing him on the spot, he is taken out and set free along with Barnaby. But now we move on to Dennis who seemed to have disappeared since their entrance into the jail and is now in the condemned rooms, in which there are four men waiting for the rioters to free them. Dennis, however, has no intention of freeing them, for they have been found guilty and have been sentenced to be worked off by him in a few days. He seems very fond of working people off. He tells them he is there to take care of them and see that they don't burn but instead die of the other thing. He tells them to stop screaming for then they will lose their voices which will be a shame when it comes to making speeches before the hanging. A very strange person is Dennis. But now here come Hugh and the rioters and a wedge is driven between the two "friends":

‘Halloa!’ cried Hugh, who was the first to look into the dusky passage: ‘Dennis before us! Well done, old boy. Be quick, and open here, for we shall be suffocated in the smoke, going out.’

‘Go out at once, then,’ said Dennis. ‘What do you want here?’

‘Want!’ echoed Hugh. ‘The four men.’

‘Four devils!’ cried the hangman. ‘Don’t you know they’re left for death on Thursday? Don’t you respect the law—the constitootion—nothing? Let the four men be.’

‘Is this a time for joking?’ cried Hugh. ‘Do you hear ‘em? Pull away these bars that have got fixed between the door and the ground; and let us in.’

‘Brother,’ said the hangman, in a low voice, as he stooped under pretence of doing what Hugh desired, but only looked up in his face, ‘can’t you leave these here four men to me, if I’ve the whim! You do what you like, and have what you like of everything for your share,—give me my share. I want these four men left alone, I tell you!’

‘Pull the bars down, or stand out of the way,’ was Hugh’s reply.

‘You can turn the crowd if you like, you know that well enough, brother,’ said the hangman, slowly. ‘What! You WILL come in, will you?’

‘Yes.’

‘You won’t let these men alone, and leave ‘em to me? You’ve no respect for nothing—haven’t you?’ said the hangman, retreating to the door by which he had entered, and regarding his companion with a scowl. ‘You WILL come in, will you, brother!’

‘I tell you, yes. What the devil ails you? Where are you going?’

‘No matter where I’m going,’ rejoined the hangman, looking in again at the iron wicket, which he had nearly shut upon himself, and held ajar. ‘Remember where you’re coming. That’s all!’

With that, he shook his likeness at Hugh, and giving him a grin, compared with which his usual smile was amiable, disappeared, and shut the door.

So I wonder what this could mean for Hugh and Dennis, they worked so well together. We'll see I suppose. We end our chapter with this:

When this last task had been achieved, the shouts and cries grew fainter; the clank of fetters, which had resounded on all sides as the prisoners escaped, was heard no more; all the noises of the crowd subsided into a hoarse and sullen murmur as it passed into the distance; and when the human tide had rolled away, a melancholy heap of smoking ruins marked the spot where it had lately chafed and roared.

Anon some famished wretch whose theft had been a loaf of bread, or scrap of butcher’s meat, came skulking past, barefooted—going slowly away because that jail, his house, was burning; not because he had any other, or had friends to meet, or old haunts to revisit, or any liberty to gain, but liberty to starve and die.

Old Rudge hears the noise, sees the fire, sees the rioters, and is convinced they are coming to kill him having heard of his monstrous act. That there are men there that have probably committed the same monstrous acts doesn't seem to occur to him and he remains hidden as best he can in the dark corner of his cell. But they eventually enter his cell and instead of killing him on the spot, he is taken out and set free along with Barnaby. But now we move on to Dennis who seemed to have disappeared since their entrance into the jail and is now in the condemned rooms, in which there are four men waiting for the rioters to free them. Dennis, however, has no intention of freeing them, for they have been found guilty and have been sentenced to be worked off by him in a few days. He seems very fond of working people off. He tells them he is there to take care of them and see that they don't burn but instead die of the other thing. He tells them to stop screaming for then they will lose their voices which will be a shame when it comes to making speeches before the hanging. A very strange person is Dennis. But now here come Hugh and the rioters and a wedge is driven between the two "friends":

‘Halloa!’ cried Hugh, who was the first to look into the dusky passage: ‘Dennis before us! Well done, old boy. Be quick, and open here, for we shall be suffocated in the smoke, going out.’

‘Go out at once, then,’ said Dennis. ‘What do you want here?’

‘Want!’ echoed Hugh. ‘The four men.’

‘Four devils!’ cried the hangman. ‘Don’t you know they’re left for death on Thursday? Don’t you respect the law—the constitootion—nothing? Let the four men be.’

‘Is this a time for joking?’ cried Hugh. ‘Do you hear ‘em? Pull away these bars that have got fixed between the door and the ground; and let us in.’

‘Brother,’ said the hangman, in a low voice, as he stooped under pretence of doing what Hugh desired, but only looked up in his face, ‘can’t you leave these here four men to me, if I’ve the whim! You do what you like, and have what you like of everything for your share,—give me my share. I want these four men left alone, I tell you!’

‘Pull the bars down, or stand out of the way,’ was Hugh’s reply.

‘You can turn the crowd if you like, you know that well enough, brother,’ said the hangman, slowly. ‘What! You WILL come in, will you?’

‘Yes.’

‘You won’t let these men alone, and leave ‘em to me? You’ve no respect for nothing—haven’t you?’ said the hangman, retreating to the door by which he had entered, and regarding his companion with a scowl. ‘You WILL come in, will you, brother!’

‘I tell you, yes. What the devil ails you? Where are you going?’

‘No matter where I’m going,’ rejoined the hangman, looking in again at the iron wicket, which he had nearly shut upon himself, and held ajar. ‘Remember where you’re coming. That’s all!’

With that, he shook his likeness at Hugh, and giving him a grin, compared with which his usual smile was amiable, disappeared, and shut the door.

So I wonder what this could mean for Hugh and Dennis, they worked so well together. We'll see I suppose. We end our chapter with this:

When this last task had been achieved, the shouts and cries grew fainter; the clank of fetters, which had resounded on all sides as the prisoners escaped, was heard no more; all the noises of the crowd subsided into a hoarse and sullen murmur as it passed into the distance; and when the human tide had rolled away, a melancholy heap of smoking ruins marked the spot where it had lately chafed and roared.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 61 starts ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 61 starts ..."Thanks, Kim, for the information on the real Kennett and Fielding. The Fieldings sound like quite an impressive family. Hard to imagine a time when there wasn't a professional police force. But it also makes it easier to understand Haredale's "citizen's arrest" of the elder Rudge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_co...

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 63 I realized something you cannot tell my husband, I am in love with Gabriel Varden. I could just go on putting in one Gabriel comment after another and call the chapter good, so I thin..."

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 63 I realized something you cannot tell my husband, I am in love with Gabriel Varden. I could just go on putting in one Gabriel comment after another and call the chapter good, so I thin..."I won't tell, Kim. I've got a bit of a crush on him, myself.

Where on Earth is Mary Varden, and why isn't Miggs with her? Literary convenience? I hope not, but I fear so. As for Miggs, well... as fond as I am of Gabriel, he's much too lenient as an employer, and she and Sim both should have been dismissed long ago.

Kim wrote: "we may have to keep those two in mind, especially that one armed man. ..."

Kim wrote: "we may have to keep those two in mind, especially that one armed man. ..."That one-armed man is popping up all over the place, isn't he? I wonder where he's taken Gabriel, and if Gabriel is will be okay. What am I saying? Of course he will. But for now, the Vardens all seem to be unaccounted for.

I wonder if Haredale has taken Langdale, the vinter, up on his offer of a place to stay -- assuming, of course, that Langdale's house was spared. I'm sure he wants to track down the ladies, but where on Earth would he start to look?

With all of the despicable behavior we're witnessing in these chapters, I'm pleased to see that we've also had the pleasure of meeting a few other stand-up guys who balance the scales a bit.

PS This chapter contains one of the longest run-on sentences I've seen in awhile. Long even by Dickens' standards, I think. If you can find more than one period in all of this, let me know.

At first they crowded round the blaze, and vented their exultation only in their looks: but when it grew hotter and fiercer—when it crackled, leaped, and roared, like a great furnace—when it shone upon the opposite houses, and lighted up not only the pale and wondering faces at the windows, but the inmost corners of each habitation— when through the deep red heat and glow, the fire was seen sporting and toying with the door, now clinging to its obdurate surface, now gliding off with fierce inconstancy and soaring high into the sky, anon returning to fold it in its burning grasp and lure it to its ruin—when it shone and gleamed so brightly that the church clock of St Sepulchre’s so often pointing to the hour of death, was legible as in broad day, and the vane upon its steeple-top glittered in the unwonted light like something richly jewelled— when blackened stone and somber brick grew ruddy in the deep reflection, and windows shone like burnished gold, dotting the longest distance in the fiery vista with their specks of brightness—when wall and tower, and roof and chimney-stack, seemed drunk, and in the flickering glare appeared to reel and stagger— when scores of objects, never seen before, burst out upon the view, and things the most familiar put on some new aspect—then the mob began to join the whirl, and with loud yells, and shouts, and clamour, such as happily is seldom heard, bestirred themselves to feed the fire, and keep it at its height.

Thanks, Kim, good job. I was surprised that finally Hugh is doing something humane in releasing the last condemned prisoners from the burning jail. At least he is not leaving them to burn with the jail as Dennis wants.

Thanks, Kim, good job. I was surprised that finally Hugh is doing something humane in releasing the last condemned prisoners from the burning jail. At least he is not leaving them to burn with the jail as Dennis wants. My main question at this point is where is Joe Willett and Edward Chester. I have expected them to show up again. Well, maybe in the next section in time to rescue the kidnapped girls, or will it be Haredale and Varden who accomplish that?

And, yes, were is the police who should be watching the prison to avoid this. It does seem that there is little to no enforcement of any kind.

Kim wrote: "Chapter 65 ..."

Kim wrote: "Chapter 65 ..."That Dennis is a piece of work, isn't he? He certainly does enjoy his work. Cruel as he was, I have to admit to enjoying his "give it mouth" speech.

When I read this sentence, I thought for sure that Dennis had somehow locked Hugh in with the prisoners, and they would all burn together:

With that, he shook his likeness at Hugh, and giving him a grin, compared with which his usual smile was amiable, disappeared, and shut the door.

Missed the mark on that one. But one does wonder what will happen when Hugh and Dennis meet again.

Am I the only one who busted up laughing at this exchange?

‘What do you want here?’

‘Want!’ echoed Hugh. ‘The four men.’

‘Four devils!’ cried the hangman. ‘Don’t you know they’re left for death on Thursday? Don’t you respect the law—the constitootion— nothing?’

Ha!

Mary Lou wrote: "Kim wrote: "Chapter 61 starts ..."

Thanks, Kim, for the information on the real Kennett and Fielding. The Fieldings sound like quite an impressive family. Hard to imagine a time when there wasn't ..."

Mary Lou

Classic footage. What a way to begin my Saturday. I think I’ll take a bus.

Thanks, Kim, for the information on the real Kennett and Fielding. The Fieldings sound like quite an impressive family. Hard to imagine a time when there wasn't ..."

Mary Lou

Classic footage. What a way to begin my Saturday. I think I’ll take a bus.

Thank you, Kim!

I wouldn't be surprised if the one-armed man was either Joe or Edward. It would be typical, I think, to look back and say ooooh yes, off course, he was there all the time, I just didn't know yet!

With every chapter he appears, I dislike Dennis the more. The way he likes hanging people, he is the kind of hangman that just loves to kill people - and with his profession he can kill more people every month than most murderers he hangs have killed in total, without being hanged himself. He enjoys it far too much!

I wouldn't be surprised if the one-armed man was either Joe or Edward. It would be typical, I think, to look back and say ooooh yes, off course, he was there all the time, I just didn't know yet!

With every chapter he appears, I dislike Dennis the more. The way he likes hanging people, he is the kind of hangman that just loves to kill people - and with his profession he can kill more people every month than most murderers he hangs have killed in total, without being hanged himself. He enjoys it far too much!

Kim wrote: "Hello again friends,

Tristram is still doing whatever it is he does when he and his family are on their holiday, so once again you are stuck with me. I won't be home from this evening until late S..."

Kim

“Another bead in the long rosary of his regrets”. Thanks for pointing the phrase out to us. It’s phrases like this that keep me in awe of Dickens.

This chapter shows us how quickly events and people change. Doors close and people reject Haredale not because of who he is but because of what he is. When we see the relationship blossom so quickly between Haredale and Langdale we become aware of the fact that even while the rioters have changed the landscape of England, and especially London, there still remain people who are willing to reach out and help others rather than push them away for no reason.

Tristram is still doing whatever it is he does when he and his family are on their holiday, so once again you are stuck with me. I won't be home from this evening until late S..."

Kim

“Another bead in the long rosary of his regrets”. Thanks for pointing the phrase out to us. It’s phrases like this that keep me in awe of Dickens.

This chapter shows us how quickly events and people change. Doors close and people reject Haredale not because of who he is but because of what he is. When we see the relationship blossom so quickly between Haredale and Langdale we become aware of the fact that even while the rioters have changed the landscape of England, and especially London, there still remain people who are willing to reach out and help others rather than push them away for no reason.

Kim wrote: "In Chapter 62 we find ourselves in jail with Old Rudge and unfortunately with Barnaby also. It is most unfortunate for Old Rudge because he is not aware Barnaby is there and so the plan the blind m..."

In this chapter we see how Mr Barnaby has been, in fact, in two prisons. The second is the physical one that he finds himself in now. The first prison sentence is a psychological one that Mr Barnaby placed himself in 28 years ago. There was no place and no distance that freed him from the haunting memories of his two murders. No matter where he went, or what he did, his mind continually plagued him with his crimes.

There is an interesting symmetry in Mr Barnaby’s two incarcerations. He has been drawn back to the Warren, the place where the murders occurred. He is captured and arrested by the brother of one of the men he killed. Justice has come full circle.

In this chapter we see how Mr Barnaby has been, in fact, in two prisons. The second is the physical one that he finds himself in now. The first prison sentence is a psychological one that Mr Barnaby placed himself in 28 years ago. There was no place and no distance that freed him from the haunting memories of his two murders. No matter where he went, or what he did, his mind continually plagued him with his crimes.

There is an interesting symmetry in Mr Barnaby’s two incarcerations. He has been drawn back to the Warren, the place where the murders occurred. He is captured and arrested by the brother of one of the men he killed. Justice has come full circle.

Kim wrote: "After the fun I had with Gabriel Varden in the last chapter I find him in the next in much more danger as he continues his refusal to help the rioters to the end. The mob, always led by Hugh and De..."

Who could not respect Varden after reading this chapter? We learn that he is a multi-dimensional man. To his daughter Dolly he is a kind, loving, and generous man. To his wife he is patient, forgiving, and perhaps a wee bit selectively deaf, to Miggs he is tolerant, and to Tappertit he is an ideal master for any apprentice. It is in this chapter, however, we see yet another dimension to him, although perhaps we should not b surprised.

In this chapter we see a principled man, a man who believes in the rule of law and a man who will not be humbled by those who are physically abusive, hateful, revengeful, or rabidly angry. Knock him down, up he gets. I think Dickens’s creation of Varden gives us an outline of the true Englishman. The more Dennis, Hugh, and the others try to force Varden to do their will, the stronger Varden becomes. At one point in the early stages of the conception of this novel Dickens planned to name it after Varden. I would have been fine with that, although Barnaby is also a fascinating creation. We have a novel titled A Tale of Two Cities; here, perhaps, we have a novel with two protagonists.

Who could not respect Varden after reading this chapter? We learn that he is a multi-dimensional man. To his daughter Dolly he is a kind, loving, and generous man. To his wife he is patient, forgiving, and perhaps a wee bit selectively deaf, to Miggs he is tolerant, and to Tappertit he is an ideal master for any apprentice. It is in this chapter, however, we see yet another dimension to him, although perhaps we should not b surprised.

In this chapter we see a principled man, a man who believes in the rule of law and a man who will not be humbled by those who are physically abusive, hateful, revengeful, or rabidly angry. Knock him down, up he gets. I think Dickens’s creation of Varden gives us an outline of the true Englishman. The more Dennis, Hugh, and the others try to force Varden to do their will, the stronger Varden becomes. At one point in the early stages of the conception of this novel Dickens planned to name it after Varden. I would have been fine with that, although Barnaby is also a fascinating creation. We have a novel titled A Tale of Two Cities; here, perhaps, we have a novel with two protagonists.

Mary Lou write: "PS This chapter contains one of the longest run-on sentences I've seen in awhile.

Hearing that the shortest verse in the Bible is "Jesus wept" over and over my entire life, I once decided to find out what the longest verse is. It's not even close to what Dickens can do.

Esther 8:9 “The king’s scribes were summoned at that time, in the third month, which is the month of Sivan, on the twenty-third day. And an edict was written, according to all that Mordecai commanded concerning the Jews, to the satraps and the governors and the officials of the provinces from India to Ethiopia, 127 provinces, to each province in its own script and to each people in its own language, and also to the Jews in their script and their language.”

Hearing that the shortest verse in the Bible is "Jesus wept" over and over my entire life, I once decided to find out what the longest verse is. It's not even close to what Dickens can do.

Esther 8:9 “The king’s scribes were summoned at that time, in the third month, which is the month of Sivan, on the twenty-third day. And an edict was written, according to all that Mordecai commanded concerning the Jews, to the satraps and the governors and the officials of the provinces from India to Ethiopia, 127 provinces, to each province in its own script and to each people in its own language, and also to the Jews in their script and their language.”

Mary Lou wrote: "I won't tell, Kim. I've got a bit of a crush on him, myself..."

Mary Lou wrote: "I won't tell, Kim. I've got a bit of a crush on him, myself..."You both have good taste!

Mary Lou wrote: "Where on Earth is Mary Varden, and why isn't Miggs with her? Literary convenience? I hope not, but I fear so..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Where on Earth is Mary Varden, and why isn't Miggs with her? Literary convenience? I hope not, but I fear so..."I thought this was Mary?

...some one at the window cried:

‘He has a grey head. He is an old man: Don’t hurt him!

But now I'm not sure, because this comes right after and is kind of ambiguous:

The locksmith turned, with a start, towards the place from which the words had come, and looked hurriedly at the people who were hanging on the ladder and clinging to each other.

‘Pay no respect to my grey hair, young man,’ he said, answering the voice and not any one he saw.

Is the person who intervened the "young man" then, and not a woman? And if so, who would that young man be? Is this the one-armed guy again? I'm confused.

Mary Lou wrote: This chapter contains one of the longest run-on sentences I've seen in awhile. Long even by Dickens' standards, I think. If you can find more than one period in all of this, let me know...."

Mary Lou wrote: This chapter contains one of the longest run-on sentences I've seen in awhile. Long even by Dickens' standards, I think. If you can find more than one period in all of this, let me know...."I loved that sentence (and that chapter). I think the way it speeds on and on and away captures the mob's inability to stop--it's carried away by its own momentum.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "After the fun I had with Gabriel Varden in the last chapter I find him in the next in much more danger as he continues his refusal to help the rioters to the end. The mob, always led by..."

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "After the fun I had with Gabriel Varden in the last chapter I find him in the next in much more danger as he continues his refusal to help the rioters to the end. The mob, always led by..."Yes in this chapter you have to admire G. Varden. A little wishy- washy up til now but he shows his full muster.

The Murderer's Confession

Chapter 62

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

After a long time the door of his cell opened. He looked up; saw the blind man enter; and relapsed into his former position.

Guided by his breathing, the visitor advanced to where he sat; and stopping beside him, and stretching out his hand to assure himself that he was right, remained, for a good space, silent.

‘This is bad, Rudge. This is bad,’ he said at length.

The prisoner shuffled with his feet upon the ground in turning his body from him, but made no other answer.

‘How were you taken?’ he asked. ‘And where? You never told me more than half your secret. No matter; I know it now. How was it, and where, eh?’ he asked again, coming still nearer to him.

‘At Chigwell,’ said the other.

‘At Chigwell! How came you there?’

‘Because I went there to avoid the man I stumbled on,’ he answered. ‘Because I was chased and driven there, by him and Fate. Because I was urged to go there, by something stronger than my own will. When I found him watching in the house she used to live in, night after night, I knew I never could escape him—never! and when I heard the Bell—’

He shivered; muttered that it was very cold; paced quickly up and down the narrow cell; and sitting down again, fell into his old posture.

‘You were saying,’ said the blind man, after another pause, ‘that when you heard the Bell—’

‘Let it be, will you?’ he retorted in a hurried voice. ‘It hangs there yet.’

The blind man turned a wistful and inquisitive face towards him, but he continued to speak, without noticing him.

‘I went to Chigwell, in search of the mob. I have been so hunted and beset by this man, that I knew my only hope of safety lay in joining them. They had gone on before; I followed them when it left off.’

‘When what left off?’

‘The Bell. They had quitted the place. I hoped that some of them might be still lingering among the ruins, and was searching for them when I heard—’ he drew a long breath, and wiped his forehead with his sleeve—‘his voice.’

‘Saying what?’

‘No matter what. I don’t know. I was then at the foot of the turret, where I did the—’

‘Ay,’ said the blind man, nodding his head with perfect composure, ‘I understand.’

‘I climbed the stair, or so much of it as was left; meaning to hide till he had gone. But he heard me; and followed almost as soon as I set foot upon the ashes.’

‘You might have hidden in the wall, and thrown him down, or stabbed him,’ said the blind man.

‘Might I? Between that man and me, was one who led him on—I saw it, though he did not—and raised above his head a bloody hand. It was in the room above that HE and I stood glaring at each other on the night of the murder, and before he fell he raised his hand like that, and fixed his eyes on me. I knew the chase would end there.’

‘You have a strong fancy,’ said the blind man, with a smile.

‘Strengthen yours with blood, and see what it will come to.’

He groaned, and rocked himself, and looking up for the first time, said, in a low, hollow voice:

‘Eight-and-twenty years! Eight-and-twenty years! He has never changed in all that time, never grown older, nor altered in the least degree. He has been before me in the dark night, and the broad sunny day; in the twilight, the moonlight, the sunlight, the light of fire, and lamp, and candle; and in the deepest gloom. Always the same! In company, in solitude, on land, on shipboard; sometimes leaving me alone for months, and sometimes always with me. I have seen him, at sea, come gliding in the dead of night along the bright reflection of the moon in the calm water; and I have seen him, on quays and market-places, with his hand uplifted, towering, the centre of a busy crowd, unconscious of the terrible form that had its silent stand among them. Fancy! Are you real? Am I? Are these iron fetters, riveted on me by the smith’s hammer, or are they fancies I can shatter at a blow?’

Colored not colored, you decide:

Father and Son

Chapter 62

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, square yard, made cold and gloomy by high walls, and seeming to chill the very sunlight. The stone, so bare, and rough, and obdurate, filled even him with longing thoughts of meadow-land and trees; and with a burning wish to be at liberty. As he looked, he rose, and leaning against the door-post, gazed up at the bright blue sky, smiling even on that dreary home of crime. He seemed, for a moment, to remember lying on his back in some sweet-scented place, and gazing at it through moving branches, long ago.

His attention was suddenly attracted by a clanking sound—he knew what it was, for he had startled himself by making the same noise in walking to the door. Presently a voice began to sing, and he saw the shadow of a figure on the pavement. It stopped—was silent all at once, as though the person for a moment had forgotten where he was, but soon remembered—and so, with the same clanking noise, the shadow disappeared.

He walked out into the court and paced it to and fro; startling the echoes, as he went, with the harsh jangling of his fetters. There was a door near his, which, like his, stood ajar.

He had not taken half-a-dozen turns up and down the yard, when, standing still to observe this door, he heard the clanking sound again. A face looked out of the grated window—he saw it very dimly, for the cell was dark and the bars were heavy—and directly afterwards, a man appeared, and came towards him.

For the sense of loneliness he had, he might have been in jail a year. Made eager by the hope of companionship, he quickened his pace, and hastened to meet the man half way—

What was this! His son!

They stood face to face, staring at each other. He shrinking and cowed, despite himself; Barnaby struggling with his imperfect memory, and wondering where he had seen that face before. He was not uncertain long, for suddenly he laid hands upon him, and striving to bear him to the ground, cried:

‘Ah! I know! You are the robber!’

He said nothing in reply at first, but held down his head, and struggled with him silently. Finding the younger man too strong for him, he raised his face, looked close into his eyes, and said,

‘I am your father.’

God knows what magic the name had for his ears; but Barnaby released his hold, fell back, and looked at him aghast. Suddenly he sprung towards him, put his arms about his neck, and pressed his head against his cheek.

Yes, yes, he was; he was sure he was. But where had he been so long, and why had he left his mother by herself, or worse than by herself, with her poor foolish boy? And had she really been as happy as they said? And where was she? Was she near there? She was not happy now, and he in jail? Ah, no.

Not a word was said in answer; but Grip croaked loudly, and hopped about them, round and round, as if enclosing them in a magic circle, and invoking all the powers of mischief.

I find it interesting, and slightly confusing, that one of the sites I get the illustrations from usually has two of them joined together with different captions than the ones in the book. Here is one of them:

Father and Son

Chapter 62

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, square yard, made cold and gloomy by high walls, and seeming to chill the very sunlight. The stone, so bare, and rough, and obdurate, filled even him with longing thoughts of meadow-land and trees; and with a burning wish to be at liberty. As he looked, he rose, and leaning against the door-post, gazed up at the bright blue sky, smiling even on that dreary home of crime. He seemed, for a moment, to remember lying on his back in some sweet-scented place, and gazing at it through moving branches, long ago.

His attention was suddenly attracted by a clanking sound—he knew what it was, for he had startled himself by making the same noise in walking to the door. Presently a voice began to sing, and he saw the shadow of a figure on the pavement. It stopped—was silent all at once, as though the person for a moment had forgotten where he was, but soon remembered—and so, with the same clanking noise, the shadow disappeared.

He walked out into the court and paced it to and fro; startling the echoes, as he went, with the harsh jangling of his fetters. There was a door near his, which, like his, stood ajar.

He had not taken half-a-dozen turns up and down the yard, when, standing still to observe this door, he heard the clanking sound again. A face looked out of the grated window—he saw it very dimly, for the cell was dark and the bars were heavy—and directly afterwards, a man appeared, and came towards him.

For the sense of loneliness he had, he might have been in jail a year. Made eager by the hope of companionship, he quickened his pace, and hastened to meet the man half way—

What was this! His son!

They stood face to face, staring at each other. He shrinking and cowed, despite himself; Barnaby struggling with his imperfect memory, and wondering where he had seen that face before. He was not uncertain long, for suddenly he laid hands upon him, and striving to bear him to the ground, cried:

‘Ah! I know! You are the robber!’

He said nothing in reply at first, but held down his head, and struggled with him silently. Finding the younger man too strong for him, he raised his face, looked close into his eyes, and said,

‘I am your father.’

God knows what magic the name had for his ears; but Barnaby released his hold, fell back, and looked at him aghast. Suddenly he sprung towards him, put his arms about his neck, and pressed his head against his cheek.

Yes, yes, he was; he was sure he was. But where had he been so long, and why had he left his mother by herself, or worse than by herself, with her poor foolish boy? And had she really been as happy as they said? And where was she? Was she near there? She was not happy now, and he in jail? Ah, no.

Not a word was said in answer; but Grip croaked loudly, and hopped about them, round and round, as if enclosing them in a magic circle, and invoking all the powers of mischief.

I find it interesting, and slightly confusing, that one of the sites I get the illustrations from usually has two of them joined together with different captions than the ones in the book. Here is one of them:

The abduction of Miss Miggs

Chapter 63

Max Cowper

Text Illustrated:

They looked at one another, and quickly dispersing, swarmed over the house, plundering and breaking, according to their custom, and carrying off such articles of value as happened to please their fancy. They had no great length of time for these proceedings, for the basket of tools was soon prepared and slung over a man’s shoulders. The preparations being now completed, and everything ready for the attack, those who were pillaging and destroying in the other rooms were called down to the workshop. They were about to issue forth, when the man who had been last upstairs, stepped forward, and asked if the young woman in the garret (who was making a terrible noise, he said, and kept on screaming without the least cessation) was to be released?

For his own part, Simon Tappertit would certainly have replied in the negative, but the mass of his companions, mindful of the good service she had done in the matter of the gun, being of a different opinion, he had nothing for it but to answer, Yes. The man, accordingly, went back again to the rescue, and presently returned with Miss Miggs, limp and doubled up, and very damp from much weeping.

As the young lady had given no tokens of consciousness on their way downstairs, the bearer reported her either dead or dying; and being at some loss what to do with her, was looking round for a convenient bench or heap of ashes on which to place her senseless form, when she suddenly came upon her feet by some mysterious means, thrust back her hair, stared wildly at Mr Tappertit, cried, ‘My Simmuns’s life is not a wictim!’ and dropped into his arms with such promptitude that he staggered and reeled some paces back, beneath his lovely burden.

‘Oh bother!’ said Mr Tappertit. ‘Here. Catch hold of her, somebody. Lock her up again; she never ought to have been let out.’

‘My Simmun!’ cried Miss Miggs, in tears, and faintly. ‘My for ever, ever blessed Simmun!’

‘Hold up, will you,’ said Mr Tappertit, in a very unresponsive tone, ‘I’ll let you fall if you don’t. What are you sliding your feet off the ground for?’

‘My angel Simmuns!’ murmured Miggs—‘he promised—’

‘Promised! Well, and I’ll keep my promise,’ answered Simon, testily. ‘I mean to provide for you, don’t I? Stand up!’

‘Where am I to go? What is to become of me after my actions of this night!’ cried Miggs. ‘What resting-places now remains but in the silent tombses!’

‘I wish you was in the silent tombses, I do,’ cried Mr Tappertit, ‘and boxed up tight, in a good strong one. Here,’ he cried to one of the bystanders, in whose ear he whispered for a moment: ‘Take her off, will you. You understand where?’

The fellow nodded; and taking her in his arms, notwithstanding her broken protestations, and her struggles (which latter species of opposition, involving scratches, was much more difficult of resistance), carried her away.

The locksmith undaunted

Chapter 64

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘Mr Akerman,’ cried Gabriel, ‘Mr Akerman.’

‘I will hear no more from any of you,’ replied the governor, turning towards the speaker, and waving his hand.

‘But I am not one of them,’ said Gabriel. ‘I am an honest man, Mr Akerman; a respectable tradesman—Gabriel Varden, the locksmith. You know me?’

‘You among the crowd!’ cried the governor in an altered voice.

‘Brought here by force—brought here to pick the lock of the great door for them,’ rejoined the locksmith. ‘Bear witness for me, Mr Akerman, that I refuse to do it; and that I will not do it, come what may of my refusal. If any violence is done to me, please to remember this.’

‘Is there no way of helping you?’ said the governor.

‘None, Mr Akerman. You’ll do your duty, and I’ll do mine. Once again, you robbers and cut-throats,’ said the locksmith, turning round upon them, ‘I refuse. Ah! Howl till you’re hoarse. I refuse.’

‘Stay—stay!’ said the jailer, hastily. ‘Mr Varden, I know you for a worthy man, and one who would do no unlawful act except upon compulsion—’

‘Upon compulsion, sir,’ interposed the locksmith, who felt that the tone in which this was said, conveyed the speaker’s impression that he had ample excuse for yielding to the furious multitude who beset and hemmed him in, on every side, and among whom he stood, an old man, quite alone; ‘upon compulsion, sir, I’ll do nothing.’

‘Where is that man,’ said the keeper, anxiously, ‘who spoke to me just now?’

‘Here!’ Hugh replied.

‘Do you know what the guilt of murder is, and that by keeping that honest tradesman at your side you endanger his life!’

‘We know it very well,’ he answered, ‘for what else did we bring him here? Let’s have our friends, master, and you shall have your friend. Is that fair, lads?’

The mob replied to him with a loud Hurrah!

‘You see how it is, sir?’ cried Varden. ‘Keep ‘em out, in King George’s name. Remember what I have said. Good night!’

There was no more parley. A shower of stones and other missiles compelled the keeper of the jail to retire; and the mob, pressing on, and swarming round the walls, forced Gabriel Varden close up to the door.

In vain the basket of tools was laid upon the ground before him, and he was urged in turn by promises, by blows, by offers of reward, and threats of instant death, to do the office for which they had brought him there. ‘No,’ cried the sturdy locksmith, ‘I will not!’

He had never loved his life so well as then, but nothing could move him. The savage faces that glared upon him, look where he would; the cries of those who thirsted, like wild animals, for his blood; the sight of men pressing forward, and trampling down their fellows, as they strove to reach him, and struck at him above the heads of other men, with axes and with iron bars; all failed to daunt him. He looked from man to man, and face to face, and still, with quickened breath and lessening colour, cried firmly, ‘I will not!’

Dennis dealt him a blow upon the face which felled him to the ground. He sprung up again like a man in the prime of life, and with blood upon his forehead, caught him by the throat.

‘You cowardly dog!’ he said: ‘Give me my daughter. Give me my daughter.’

They struggled together. Some cried ‘Kill him,’ and some (but they were not near enough) strove to trample him to death. Tug as he would at the old man’s wrists, the hangman could not force him to unclench his hands.

‘Is this all the return you make me, you ungrateful monster?’ he articulated with great difficulty, and with many oaths.

‘Give me my daughter!’ cried the locksmith, who was now as fierce as those who gathered round him: ‘Give me my daughter!’

He was down again, and up, and down once more, and buffeting with a score of them, who bandied him from hand to hand, when one tall fellow, fresh from a slaughter-house, whose dress and great thigh-boots smoked hot with grease and blood, raised a pole-axe, and swearing a horrible oath, aimed it at the old man’s uncovered head. At that instant, and in the very act, he fell himself, as if struck by lightning, and over his body a one-armed man came darting to the locksmith’s side. Another man was with him, and both caught the locksmith roughly in their grasp.

‘Leave him to us!’ they cried to Hugh—struggling, as they spoke, to force a passage backward through the crowd. ‘Leave him to us. Why do you waste your whole strength on such as he, when a couple of men can finish him in as many minutes! You lose time. Remember the prisoners! remember Barnaby!’

The hangman's badinage

Chapter 65

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But this functionary of the law reserved one important piece of intelligence, and kept it snugly to himself. When he had issued his instructions relative to every other part of the building, and the mob were dispersed from end to end, and busy at their work, he took a bundle of keys from a kind of cupboard in the wall, and going by a kind of passage near the chapel (it joined the governors house, and was then on fire), betook himself to the condemned cells, which were a series of small, strong, dismal rooms, opening on a low gallery, guarded, at the end at which he entered, by a strong iron wicket, and at its opposite extremity by two doors and a thick grate. Having double locked the wicket, and assured himself that the other entrances were well secured, he sat down on a bench in the gallery, and sucked the head of his stick with the utmost complacency, tranquillity, and contentment.

It would have been strange enough, a man’s enjoying himself in this quiet manner, while the prison was burning, and such a tumult was cleaving the air, though he had been outside the walls. But here, in the very heart of the building, and moreover with the prayers and cries of the four men under sentence sounding in his ears, and their hands, stretched out through the gratings in their cell-doors, clasped in frantic entreaty before his very eyes, it was particularly remarkable. Indeed, Mr Dennis appeared to think it an uncommon circumstance, and to banter himself upon it; for he thrust his hat on one side as some men do when they are in a waggish humour, sucked the head of his stick with a higher relish, and smiled as though he would say, ‘Dennis, you’re a rum dog; you’re a queer fellow; you’re capital company, Dennis, and quite a character!’

He sat in this way for some minutes, while the four men in the cells, who were certain that somebody had entered the gallery, but could not see who, gave vent to such piteous entreaties as wretches in their miserable condition may be supposed to have been inspired with: urging, whoever it was, to set them at liberty, for the love of Heaven; and protesting, with great fervour, and truly enough, perhaps, for the time, that if they escaped, they would amend their ways, and would never, never, never again do wrong before God or man, but would lead penitent and sober lives, and sorrowfully repent the crimes they had committed. The terrible energy with which they spoke, would have moved any person, no matter how good or just (if any good or just person could have strayed into that sad place that night), to have set them at liberty: and, while he would have left any other punishment to its free course, to have saved them from this last dreadful and repulsive penalty; which never turned a man inclined to evil, and has hardened thousands who were half inclined to good.

Hugh

Artist Ron Embleton

Here is a biography on the artist:

Ronald Sydney Embleton (6 October 1930 - 13 February 1988; London, UK)

Born in Limehouse, London in 1930, Embleton began drawing as a young boy, submitting a cartoon to the News of the World at the age of 9 and, at 12, winning a national poster competition.

In 1946 Embleton went to the South-East Essex Technical College and School of Art. There he had the incredible good fortune to be taught by David Bomberg, one of the greatest – though at that time sadly under-appreciated – British artists of the twentieth century.

At 17 he earned himself a place in a commercial studio but soon left to work freelance, drawing comic strips for many of the small publishers who sprang up shortly after the war.

He was soon drawing for the major publishers. His most fondly remembered strips include Strongbow the Mighty in Mickey Mouse Weekly, Wulf the Briton in Express Weekly, Wrath of the Gods in Boys' World, Tales of the Trigan Empire and Johnny Frog in Eagle and Stingray in TV Century 21.

Embleton also provided the illustrations that appeared in the title credits for the Captain Scarlet TV series, and dozens of paintings for prints and newspaper strips. A meticulous artist, his illustrations appeared in Look and Learn for many years, amongst them the historical series Roger’s Rangers.

Oh, Wicked Wanda! was a British full-colour satirical and saucy adult comic strip, written by Frederic Mullally and drawn by Ron Embleton. The strip regularly appeared in Penthouse magazine from 1973 to 1980 and was followed by Embleton's equally saucy dark humoured Merry Widow strip, written by Penthouse founder Bob Guccione.

Less well known, however, was his equally energetic career as an oil painter. In fact, being a painter had been his life's ambition – his 'driving force', according to his daughter Gillian. It was only his remarkable success as an illustrator that in the end permanently diverted him from the painter's path.

Embleton died on 13 February 1988 at the relatively young age of 57 after a lifetime of truly prodigious artistic output of remarkable quality and astounding quantity.

Kim wrote: "Colored not colored, you decide:

Father and Son

Chapter 62

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, square yard, made cold and gloomy by high walls, and seeming to chill the very sunlight. The st..."

Kim

Thanks for the illustrations. To colour or not? My vote, when it is a Phiz illustration, will always be no colour when it is for a Dickens novel. Phiz did thousands of illustrations in his life, and many are in colour and they are fine. That said, I’m locked into the comfort of enjoying them as they originally appeared in the parts/first editions of Dickens’s novels.

When it comes to A Christmas Carol, however, the thought that the original Leech illustrations would not have been coloured would be equally disturbing.

Father and Son

Chapter 62

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

It was a dull, square yard, made cold and gloomy by high walls, and seeming to chill the very sunlight. The st..."

Kim

Thanks for the illustrations. To colour or not? My vote, when it is a Phiz illustration, will always be no colour when it is for a Dickens novel. Phiz did thousands of illustrations in his life, and many are in colour and they are fine. That said, I’m locked into the comfort of enjoying them as they originally appeared in the parts/first editions of Dickens’s novels.

When it comes to A Christmas Carol, however, the thought that the original Leech illustrations would not have been coloured would be equally disturbing.

Kim wrote: "

Hugh

Artist Ron Embleton

Here is a biography on the artist:

Ronald Sydney Embleton (6 October 1930 - 13 February 1988; London, UK)

Born in Limehouse, London in 1930, Embleton began drawing as ..."

Hugh looks like a swash-buckling pirate in this illustration. If he had a parrot on his shoulder the illustration would be perfect.

Hugh

Artist Ron Embleton

Here is a biography on the artist:

Ronald Sydney Embleton (6 October 1930 - 13 February 1988; London, UK)

Born in Limehouse, London in 1930, Embleton began drawing as ..."

Hugh looks like a swash-buckling pirate in this illustration. If he had a parrot on his shoulder the illustration would be perfect.

Kim wrote: "The hangman's badinage

Chapter 65

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But this functionary of the law reserved one important piece of intelligence, and kept it snugly to himself. When he had issued his inst..."

What an interesting illustration. Dennis certainly looks quite content with himself and his role in life. Framing him are two solid wooden doors each with a small barred window. It is a remarkable comparison to consider that the hangman is so comfortable as he sits and contemplates his upcoming employment while we observe only the hands of two prisoners who are scheduled to hang. I find it a powerful statement that those who will die remain faceless while we see Dennis in all his comfortable glory.

The two keys that rest on the floor before Dennis suggest the fate of the imprisoned men behind Dennis. The keys, like the men locked in their cells, are beyond the reach of even the hangman.

In the left side of the illustration we see an open door and steps that lead up to another door. This suggests to me that those are the stairs the prisoners will ascend on the way to the gallows. Their last act on earth will be to drop from a height and die. Chilling and ominous.

Chapter 65

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

But this functionary of the law reserved one important piece of intelligence, and kept it snugly to himself. When he had issued his inst..."

What an interesting illustration. Dennis certainly looks quite content with himself and his role in life. Framing him are two solid wooden doors each with a small barred window. It is a remarkable comparison to consider that the hangman is so comfortable as he sits and contemplates his upcoming employment while we observe only the hands of two prisoners who are scheduled to hang. I find it a powerful statement that those who will die remain faceless while we see Dennis in all his comfortable glory.

The two keys that rest on the floor before Dennis suggest the fate of the imprisoned men behind Dennis. The keys, like the men locked in their cells, are beyond the reach of even the hangman.

In the left side of the illustration we see an open door and steps that lead up to another door. This suggests to me that those are the stairs the prisoners will ascend on the way to the gallows. Their last act on earth will be to drop from a height and die. Chilling and ominous.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "Colored not colored, you decide:

So Phiz did do some colored illustrations himself? I always thought someone took his illustrations and added color to them for no real reason. It never even occurred to me that he may have did his own coloring sometimes.