The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

D&S, Chp. 32-34

Chapter 33

Major events

At the beginning of the chapter, the narrator invites us to turn ”our eyes upon two homes” and he then proceeds to contrast the two homes: One is quite luxurious and boasts a lot of signs of the owner’s taste in arts, his knowledge of games and sports and savoir-vivre, but there is still something amiss, something that betrays a certain kind of hollowness, emptiness, showiness, which is condensed wonderfully in the following sentence: ”Is it that the books have all their gold outside, and that the titles of the greater part qualify them to be companions of the prints and pictures?” A little later, we learn of a detail like a ”gaudy parrot in a burnished cage upon the table”, and then we see the owner of the house, Mr. Carker having his breakfast in the presence of the ”chafing and imprisoned bird” whose gilded hoop seems ”like a great wedding-ring”. Strangely, Mr. Carker is looking at a large portrait of a woman that looks exactly like Edith.

The other house is outside London, on the Great North Road, and it is much more modest and humble than the first abode – although, as the narrator points out, it is very neat and clean. This is the place where James Carker and his sister Harriet live, and we just witness how James is leaving for his work. In the course of this day, there are two people who come to the house while Harriet is doing the housework in her brother’s absence – one is a middle-aged gentleman who does not disclose his name but whose mannerisms show him to be a professional musician, and this man – he is no completely new visitor to Harriet – renews his offer to help her and her brother whenever they need some assistance. He also says that once a week, every Monday, he will walk past the house in order to make sure that Harriet has the opportunity to show that help is needed. The other visitor, who comes later, is a “fallen woman”, whose beauty shines through her poverty but who is also very proud of face and manner. This woman is softened by Harriet’s frank appeals to rest a little inside and to have her wounded foot dressed, and on parting she even accepts some money from Harriet.

Thoughts, quotes, and questions

The two most obvious questions should come first: Who is that proud woman? And, who is that mysterious gentleman? At to the woman, we just have to wait until the next chapter, but the man’s identity is not yet divulged here, although there are some details in the text that allow us maybe to guess who he might be. I was asking myself, however, if not telling one’s name and saying that one has the best of intentions only is normally a sure way into a person’s confidence. Harriet does not distrust him at all, and also the narrator’s voice makes it clear enough that there is no reason to be wary of that person, but still she does not take up his offer of help but she is clearly relieved by his sympathy and the spirit in which he makes his offer.

We might also ask ourselves why a comparative stranger should offer help to a brother with the past of a petty-peculator and his sister? What might his motive and reason be? He himself says that people are led by habit to think light of and ignore the misfortune of others, and to go about their own business instead – and this is a circle that he wishes to break out of. Is this a cogent argument for paying repeated visits to someone who does not know you and tell them that you know the story of their brother and just want to help?

The place where this second house is standing is something like an in-between-world between the city and the countryside, and still our narrator points out that it is a blighted countryside and one that hesitantly turns into something like a town – for example, the pleasant meadow in front of their house has now turned into a waste with the beginnings of ”mean houses” arising everywhere. In what way might this detail fall in with what earlier chapters of the novel tell us about the railroad, and the change of whole parts of London in its wake? Maybe, it also has something to do with Harriet’s reflections on the people she sees wandering towards the city but never returning:

Apart from these details of setting, the chapter is full of details like torn feet and shoes taken off these feet, or birds in gilded cages – and it’s sometimes difficult to make connections. Can you link some of the motifs we find here with other topics or plot elements of the novel?

The juxtaposition between the two homes even introduces a detail that seems to give us some background information on Carker:

May part of the venom that James Carker has in store for his brother be attributed to Harriet’s decision to share John’s fate and to leave James for John? May Carker’s resentment be based on jealousy – a feeling that we see at work in many situations and facets in this novel? Does this little detail add to or detract from Carker’s viciousness in your eyes?

Major events

At the beginning of the chapter, the narrator invites us to turn ”our eyes upon two homes” and he then proceeds to contrast the two homes: One is quite luxurious and boasts a lot of signs of the owner’s taste in arts, his knowledge of games and sports and savoir-vivre, but there is still something amiss, something that betrays a certain kind of hollowness, emptiness, showiness, which is condensed wonderfully in the following sentence: ”Is it that the books have all their gold outside, and that the titles of the greater part qualify them to be companions of the prints and pictures?” A little later, we learn of a detail like a ”gaudy parrot in a burnished cage upon the table”, and then we see the owner of the house, Mr. Carker having his breakfast in the presence of the ”chafing and imprisoned bird” whose gilded hoop seems ”like a great wedding-ring”. Strangely, Mr. Carker is looking at a large portrait of a woman that looks exactly like Edith.

The other house is outside London, on the Great North Road, and it is much more modest and humble than the first abode – although, as the narrator points out, it is very neat and clean. This is the place where James Carker and his sister Harriet live, and we just witness how James is leaving for his work. In the course of this day, there are two people who come to the house while Harriet is doing the housework in her brother’s absence – one is a middle-aged gentleman who does not disclose his name but whose mannerisms show him to be a professional musician, and this man – he is no completely new visitor to Harriet – renews his offer to help her and her brother whenever they need some assistance. He also says that once a week, every Monday, he will walk past the house in order to make sure that Harriet has the opportunity to show that help is needed. The other visitor, who comes later, is a “fallen woman”, whose beauty shines through her poverty but who is also very proud of face and manner. This woman is softened by Harriet’s frank appeals to rest a little inside and to have her wounded foot dressed, and on parting she even accepts some money from Harriet.

Thoughts, quotes, and questions

The two most obvious questions should come first: Who is that proud woman? And, who is that mysterious gentleman? At to the woman, we just have to wait until the next chapter, but the man’s identity is not yet divulged here, although there are some details in the text that allow us maybe to guess who he might be. I was asking myself, however, if not telling one’s name and saying that one has the best of intentions only is normally a sure way into a person’s confidence. Harriet does not distrust him at all, and also the narrator’s voice makes it clear enough that there is no reason to be wary of that person, but still she does not take up his offer of help but she is clearly relieved by his sympathy and the spirit in which he makes his offer.

We might also ask ourselves why a comparative stranger should offer help to a brother with the past of a petty-peculator and his sister? What might his motive and reason be? He himself says that people are led by habit to think light of and ignore the misfortune of others, and to go about their own business instead – and this is a circle that he wishes to break out of. Is this a cogent argument for paying repeated visits to someone who does not know you and tell them that you know the story of their brother and just want to help?

The place where this second house is standing is something like an in-between-world between the city and the countryside, and still our narrator points out that it is a blighted countryside and one that hesitantly turns into something like a town – for example, the pleasant meadow in front of their house has now turned into a waste with the beginnings of ”mean houses” arising everywhere. In what way might this detail fall in with what earlier chapters of the novel tell us about the railroad, and the change of whole parts of London in its wake? Maybe, it also has something to do with Harriet’s reflections on the people she sees wandering towards the city but never returning:

”She often looked with compassion, at such a time, upon the stragglers who came wandering into London, by the great highway hard by, and who, footsore and weary, and gazing fearfully at the huge town before them, as if foreboding that their misery there would be but as a drop of water in the sea, or as a grain of sea-sand on the shore, went shrinking on, cowering before the angry weather, and looking as if the very elements rejected them. Day after day, such travellers crept past, but always, as she thought, in one direction - always towards the town. Swallowed up in one phase or other of its immensity, towards which they seemed impelled by a desperate fascination, they never returned. Food for the hospitals, the churchyards, the prisons, the river, fever, madness, vice, and death, - they passed on to the monster, roaring in the distance, and were lost.”

Apart from these details of setting, the chapter is full of details like torn feet and shoes taken off these feet, or birds in gilded cages – and it’s sometimes difficult to make connections. Can you link some of the motifs we find here with other topics or plot elements of the novel?

The juxtaposition between the two homes even introduces a detail that seems to give us some background information on Carker:

”She [i.e. Harriet] withdrew from that home [i.e. James’s] its redeeming spirit, and from its master's breast his solitary angel: but though his liking for her is gone, after this ungrateful slight as he considers it; and though he abandons her altogether in return, an old idea of her is not quite forgotten even by him. Let her flower-garden, in which he never sets his foot, but which is yet maintained, among all his costly alterations, as if she had quitted it but yesterday, bear witness!”

May part of the venom that James Carker has in store for his brother be attributed to Harriet’s decision to share John’s fate and to leave James for John? May Carker’s resentment be based on jealousy – a feeling that we see at work in many situations and facets in this novel? Does this little detail add to or detract from Carker’s viciousness in your eyes?

Chapter 34

Major events

Chapter 34 reintroduces us to Good Mrs. Brown, who is sitting in an ugly, dark room somewhere in London and who is surprised by a female visitor that turns out to be her daughter Alice. You probably remember that Mrs. Brown, when she held Florence captive, was only dissuaded from cutting off the girl’s hair by the memory of the beauty of her own daugther’s hair, and very hard it was for that old woman to check her greed. Now, it is the beautiful daughter who has returned, and despite the mother’s profusion of welcoming words and signs of joy, the daughter Alice Marwood (so, Mrs. Brown’s real name must surely be Marwood as well) reacts less cordially and apparently holds a grudge against her mother. In the course of their conversation it also becomes clear, why: Apparently, Mrs. Brown’s influence was at least partly responsible for the development her daughter’s life had taken – apparently, relying too much on her charms and beauty (and being taught in this vein by her mother, among others), Alice had become a prostitute and a petty criminal. Their conversation seems very much to turn into a quarrel but Alice finally relents, and there are also tokens of the mother’s genuine anguish. Some minutes later have the two talk about how the mother got by during Alice’s absence, and then Mrs. Brown tells her that she has been observing the Dombey family since she came across Florence. They also appear to have a malevolent kind of interest in Mr. Dombey’s marriage to Edith, but most of their malevolence centres on Mr. James Carker. This finally backfires on Mrs. Brown and her wish for a dinner that would fill her stomach because when the mother tells Alice about Mr. Carker’s brother and sister and where they live, Alice realizes that it must have been Harriet who gave her shelter and the money she was about to spend on their food. Notwithstanding her mother’s remonstrances and moaning, she walks back all the way to the house, her mother in tow, in order to fling the money at Harriet’s feet and to curse her for the benevolence she received.

Thoughts, quotes, and questions

Even before the final words of this chapter, and without referring to its title, we will surely have noticed the parallels between Alice and her mother and the one hand and Mrs. Skewton and Edith on the other: Both daughters are extremely beautiful, but also regardless of this beauty and haughty, and both have the impression that their own mothers had somehow sold them. Do you think that the following words could also have been said by Edith?

By having the narrative voice more or less directly point out the similarities between these two mothers and their daughters, Dickens basically links prostitution and the kind of marriage game Mrs. Skewton plays with her own daughter as a pawn. – Do you think he is exaggerating here? How might his readers have reacted?

”’[…] Your childhood was like mine, I suppose. […]’”, Alice eventually says when she has set her mother’s notions of dutifulness on the daughter’s part right. Is Alice different in this from Edith, and what does it show about how Dickens paints his characters in Dombey and Son in opposition to some of his earlier novels? Let’s also consider these sentences:

Alice’s reaction at the end of the chapter is definitely like an explosion: Unlike Edith, who submits to her mother’s plans and marries a man she does not love, Alice does exactly what she wants, and her mother dares not but complain carefully. Can you understand her decision to decline help from the sister of someone who must have wronged her – and I think we all know what kind of wrong that was, although we can only guess as to the nearer circumstances of it? Apparently, Harriet can understand Alice’s wrath because she hears her out and also keeps her brother from interfering. But in what way can this example of bridling pride fit into the larger frame of the novel? – By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?

Major events

Chapter 34 reintroduces us to Good Mrs. Brown, who is sitting in an ugly, dark room somewhere in London and who is surprised by a female visitor that turns out to be her daughter Alice. You probably remember that Mrs. Brown, when she held Florence captive, was only dissuaded from cutting off the girl’s hair by the memory of the beauty of her own daugther’s hair, and very hard it was for that old woman to check her greed. Now, it is the beautiful daughter who has returned, and despite the mother’s profusion of welcoming words and signs of joy, the daughter Alice Marwood (so, Mrs. Brown’s real name must surely be Marwood as well) reacts less cordially and apparently holds a grudge against her mother. In the course of their conversation it also becomes clear, why: Apparently, Mrs. Brown’s influence was at least partly responsible for the development her daughter’s life had taken – apparently, relying too much on her charms and beauty (and being taught in this vein by her mother, among others), Alice had become a prostitute and a petty criminal. Their conversation seems very much to turn into a quarrel but Alice finally relents, and there are also tokens of the mother’s genuine anguish. Some minutes later have the two talk about how the mother got by during Alice’s absence, and then Mrs. Brown tells her that she has been observing the Dombey family since she came across Florence. They also appear to have a malevolent kind of interest in Mr. Dombey’s marriage to Edith, but most of their malevolence centres on Mr. James Carker. This finally backfires on Mrs. Brown and her wish for a dinner that would fill her stomach because when the mother tells Alice about Mr. Carker’s brother and sister and where they live, Alice realizes that it must have been Harriet who gave her shelter and the money she was about to spend on their food. Notwithstanding her mother’s remonstrances and moaning, she walks back all the way to the house, her mother in tow, in order to fling the money at Harriet’s feet and to curse her for the benevolence she received.

Thoughts, quotes, and questions

Even before the final words of this chapter, and without referring to its title, we will surely have noticed the parallels between Alice and her mother and the one hand and Mrs. Skewton and Edith on the other: Both daughters are extremely beautiful, but also regardless of this beauty and haughty, and both have the impression that their own mothers had somehow sold them. Do you think that the following words could also have been said by Edith?

“’[…] Why should I be penitent , and all the world go free? They talk to me of my penitence. Who’s penitent for the wrongs that have been done to me?’” (from the preceding chapter)

”‘It sounds unnatural, don‘t it?’ returned the daughter, looking coldly on her with her stern, regardless, hardy, beautiful face; ‘but I have thought of it sometimes, in the course of my lone years, till I have got used to it. I have heard some talk about duty first and last; but it has always been of my duty to other people. I have wondered now and then - to pass away the time - whether no one ever owed any duty to me.’”

By having the narrative voice more or less directly point out the similarities between these two mothers and their daughters, Dickens basically links prostitution and the kind of marriage game Mrs. Skewton plays with her own daughter as a pawn. – Do you think he is exaggerating here? How might his readers have reacted?

”’[…] Your childhood was like mine, I suppose. […]’”, Alice eventually says when she has set her mother’s notions of dutifulness on the daughter’s part right. Is Alice different in this from Edith, and what does it show about how Dickens paints his characters in Dombey and Son in opposition to some of his earlier novels? Let’s also consider these sentences:

”She admired her daughter, and was afraid of her. Perhaps her admiration, such as it was, had originated long ago, when she first found anything that was beautiful appearing in the midst of the squalid fight of her existence.”

Alice’s reaction at the end of the chapter is definitely like an explosion: Unlike Edith, who submits to her mother’s plans and marries a man she does not love, Alice does exactly what she wants, and her mother dares not but complain carefully. Can you understand her decision to decline help from the sister of someone who must have wronged her – and I think we all know what kind of wrong that was, although we can only guess as to the nearer circumstances of it? Apparently, Harriet can understand Alice’s wrath because she hears her out and also keeps her brother from interfering. But in what way can this example of bridling pride fit into the larger frame of the novel? – By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?

I'm a bit behind on my reading - since the libraries will be opened up this Monday, I wanted to make sure to have read at least two of my three library books, so that's what I've been reading. I did read chapter 32. These two characters that started being so ... awkward, in a funny but sad way, because indeed, there seems to be something with Toots. I'm not sure if he is or is not smart. He at least does not fit with Blimber's way of teaching, but then, who does? He also seems very wise in this chapter. In Dungeons and Dragons there's a clear difference between intelligence and wisdom, and it's mostly the difference between knowing what makes people tick is a heart that pumps around blood in x times a minute and the blood has x speed, and having the insight what makes people tick beyond technicalities. Toots at least has a high wisdom score. And the captain, he certainly is comic relief, but if you don't want a mutiny as a captain, you have to know how to lead people and how to make them work.

I thought it was brilliant those two came together, and to see how in the right circumstances and with the right people who acknowledged them in the right way (like they were to each other now), they both did so much better. Without the people holding them back, they knew what to do and how to act, they knew what to say.

The change of Carker towards Cuttle ... It might have been Cuttle who seems to be dangerously close to pricking through his fasçade with asking if Walter was sent away to get rid of him after all. In the earlier chapters, Cuttle had been very much believing in Carker wanting to advance Walter, and he was not that sure anymore by now. So Carker turned to gaslighting, like a proper abuser.

I thought it was brilliant those two came together, and to see how in the right circumstances and with the right people who acknowledged them in the right way (like they were to each other now), they both did so much better. Without the people holding them back, they knew what to do and how to act, they knew what to say.

The change of Carker towards Cuttle ... It might have been Cuttle who seems to be dangerously close to pricking through his fasçade with asking if Walter was sent away to get rid of him after all. In the earlier chapters, Cuttle had been very much believing in Carker wanting to advance Walter, and he was not that sure anymore by now. So Carker turned to gaslighting, like a proper abuser.

Just read chapter 33. Can it be any clearer, with the mentioning of her mother, and how much emphasis is laid on her hair, that this proud woman is old Mrs. Brown's daughter? Mrs. Brown almost cut Florence's hair, but decided against it, remembering her daughter's hair. This woman dries her hair, much is said of it, and she's quite proud of it still. I believe I will keep looking out for other times hair is mentioned.

Manager Carker's parrot seems to be a symbol for Edith. Like he caged her himself by marrying her to Dombey, and can do with her as he sees fit, because she married for Dombey's money, and he practically holds that into his hands.

Manager Carker's parrot seems to be a symbol for Edith. Like he caged her himself by marrying her to Dombey, and can do with her as he sees fit, because she married for Dombey's money, and he practically holds that into his hands.

Jantine wrote: "Manager Carker's parrot seems to be a symbol for Edith. Like he caged her himself by marrying her to Dombey, and can do with her as he sees fit, because she married for Dombey's money, and he practically holds that into his hands."

Yes, Carker holds secret knowledge about Edith, namely that she married a man for his power and his money and without loving him. His being aware of it is undoubtedly a humiliation for Edith but still I don't really know what mischief Carker can do with it - and this if for two reasons:

a) It would be very difficult to blackmail Edith, or rather it would be pointless because it's Dombey who has the money and not Edith. She will probably be given an allowance - was it not called needle-money or something like that? - but that will be small fry compared to Carker's greed.

b) Carker could blackmail Dombey, but then would good would that be? How could he blackmail him in the first place? By telling him that Edith married him for his money, rank and influence and not out of love? Why, I am not so sure that Dombey would not feel flattered by this because after all, it's testimony to his power, rank and wealth. Marrying for love is definitely not something that exists in Dombey's universe.

So, how is Carker going to play his cards?

Yes, Carker holds secret knowledge about Edith, namely that she married a man for his power and his money and without loving him. His being aware of it is undoubtedly a humiliation for Edith but still I don't really know what mischief Carker can do with it - and this if for two reasons:

a) It would be very difficult to blackmail Edith, or rather it would be pointless because it's Dombey who has the money and not Edith. She will probably be given an allowance - was it not called needle-money or something like that? - but that will be small fry compared to Carker's greed.

b) Carker could blackmail Dombey, but then would good would that be? How could he blackmail him in the first place? By telling him that Edith married him for his money, rank and influence and not out of love? Why, I am not so sure that Dombey would not feel flattered by this because after all, it's testimony to his power, rank and wealth. Marrying for love is definitely not something that exists in Dombey's universe.

So, how is Carker going to play his cards?

Tristram wrote: "Is there a better way of paying homage to all the memories that tie you to a lifetime of experiences connected with a deceased person?..."

Tristram wrote: "Is there a better way of paying homage to all the memories that tie you to a lifetime of experiences connected with a deceased person?..."I loved that speech so much, and then I loved the speech where silly Toots (but wise, as Jantine says) confesses his love for Florence:

Mine ain’t a selfish affection, you know,’ said Mr Toots, in the confidence engendered by his having been a witness of the Captain’s tenderness. ‘It’s the sort of thing with me, Captain Gills, that if I could be run over—or—or trampled upon—or—or thrown off a very high place-or anything of that sort—for Miss Dombey’s sake, it would be the most delightful thing that could happen to me.’

Walter pretty much thinks the same kind of thing about Florence earlier in the book--fine, okay, she's too good for anyone--but I love the melodramatic heights to which Toots takes it, and also I believe every word he says.

Tristram wrote: "By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?"

Tristram wrote: "By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?"No, I do not. Harriet did not deserve that. Grrr.

Jantine wrote: "Just read chapter 33. Can it be any clearer, with the mentioning of her mother, and how much emphasis is laid on her hair, that this proud woman is old Mrs. Brown's daughter? Mrs. Brown almost cut ..."

Jantine

Yes, the hair. Dickens does seem to spend a curious amount of time and focus on different character’s hair. I agree we need to keep alert to where he might be headed with the hair references.

As to the bird and the cage. Good catch. I feel you are on to something very important.

Jantine

Yes, the hair. Dickens does seem to spend a curious amount of time and focus on different character’s hair. I agree we need to keep alert to where he might be headed with the hair references.

As to the bird and the cage. Good catch. I feel you are on to something very important.

Tristram wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Manager Carker's parrot seems to be a symbol for Edith. Like he caged her himself by marrying her to Dombey, and can do with her as he sees fit, because she married for Dombey's mon..."

I wonder that too. Indeed, he could not get anything out of Edith as far as I know, and Dombey would only be proud his wealth brought him such a beautiful and accomplished wife from a good family. I wonder, is it purely the things you mentioned he knows about her, or did he see something more or connect more dots than we did when they first met under Mrs. Brown's hunbot-like shouts?

I wonder that too. Indeed, he could not get anything out of Edith as far as I know, and Dombey would only be proud his wealth brought him such a beautiful and accomplished wife from a good family. I wonder, is it purely the things you mentioned he knows about her, or did he see something more or connect more dots than we did when they first met under Mrs. Brown's hunbot-like shouts?

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?"

No, I do not. Harriet did not deserve that. Grrr."

I totally agree. I did like them mirroring Edith and her mother, this chapter showing what they would have been if they had no good family name or family relations to fall back upon. But Edith's pride is a good (or at least better) kind, because it makes her want to protect Florence, the daughter of the man she is sold to. Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because this someone is related to the man she (I guess) was sold to. It's all about where the anger is directed.

Alice is rightfully angry at life, at the men who bought her, looked at her, judged her. At her mother. But she was also so bitterly angry at someone who could have been a true ally.

Btw, I forgot to mention earlier, but Harriet reminded me a lot of Martin Chuzzlewit's Ruth. Only she seems to be less dainty, a bit more down to earth, and with that more likeable to me as a modern reader.

No, I do not. Harriet did not deserve that. Grrr."

I totally agree. I did like them mirroring Edith and her mother, this chapter showing what they would have been if they had no good family name or family relations to fall back upon. But Edith's pride is a good (or at least better) kind, because it makes her want to protect Florence, the daughter of the man she is sold to. Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because this someone is related to the man she (I guess) was sold to. It's all about where the anger is directed.

Alice is rightfully angry at life, at the men who bought her, looked at her, judged her. At her mother. But she was also so bitterly angry at someone who could have been a true ally.

Btw, I forgot to mention earlier, but Harriet reminded me a lot of Martin Chuzzlewit's Ruth. Only she seems to be less dainty, a bit more down to earth, and with that more likeable to me as a modern reader.

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "By the way, do you like the Marwoods any better after this chapter?"

No, I do not. Harriet did not deserve that. Grrr."

Probably no one deserves to be measures by the deeds of their family ;-)

No, I do not. Harriet did not deserve that. Grrr."

Probably no one deserves to be measures by the deeds of their family ;-)

Jantine wrote: "I wonder, is it purely the things you mentioned he knows about her, or did he see something more or connect more dots than we did when they first met under Mrs. Brown's hunbot-like shouts?"

And this is where my bad memory serves me admirably, Jantine: I think this is the fourth - but at least the third time - I am reading this novel, and there is so much I have forgotten about Carker's machinations. Bad memory enables you to be surprised by the books you are re-reading, and that's quite something, I'd say.

And this is where my bad memory serves me admirably, Jantine: I think this is the fourth - but at least the third time - I am reading this novel, and there is so much I have forgotten about Carker's machinations. Bad memory enables you to be surprised by the books you are re-reading, and that's quite something, I'd say.

Jantine wrote: "But Edith's pride is a good (or at least better) kind, because it makes her want to protect Florence, the daughter of the man she is sold to. Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because this someone is related to the man she (I guess) was sold to."

Good point! In a way, Mrs. Brown and Alice are Mrs. Skewton and Edith at the other end of the social scale, but then they also differ. Any other differences?

Good point! In a way, Mrs. Brown and Alice are Mrs. Skewton and Edith at the other end of the social scale, but then they also differ. Any other differences?

I do feel a lot of sympathy for Alice, without knowing her whole story (and I can't wait to find out). Although Edith has had a tough time being touted around by her mother, it's really only her pride that has been hurt.

I do feel a lot of sympathy for Alice, without knowing her whole story (and I can't wait to find out). Although Edith has had a tough time being touted around by her mother, it's really only her pride that has been hurt.Alice seems to have endured desperate poverty and had to resort to actual prostitution. I don't really understand why she is walking to London (or where Carker - which one ? - is involved) but a loveless marriage to wealthy businessman seems preferable to what she seems to have endured.

Jantine wrote: "Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because this someone is related to the man she (I guess) was sold to."

Jantine wrote: "Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because this someone is related to the man she (I guess) was sold to."I have to admit that I was totally thrown by these chapters. Who was Alice sold to ? One of the Carkers presumably, but which one ?

Tristram - you said "I think we all know what kind of wrong that was".

This will be the first in a long list of dumb questions :-) but I have no idea what it might be !

I guess it will all become clear, but you guys seem to be much cleverer at picking up hints than me...

I'm still loving it here though, and reading these discussions is helping me get so much more out of this book.

It is clear Alice has been a prostitute, all of her bitterness cirles around men looking at her body and judging her, while also using her. I think we can assume Carker the manager was the start of her consciously being a fallen woman.

And on one hand I agree, I'd rather be married to Dombey than being a prostitute, especially in the Victorian time where there were not any condoms or practically failsafe ways to protect yourself from pregnancy and diseases we have now. On the other hand, is having to sell your body for money, and having to allow men to have sex with you because society has taken all other options from you, not as bad for every woman? Sure, Edith has the security that she will have a roof over her head and food on the table at all times, not depending on how often Dombey wants to have sex. But if he wants to, she has to comply, wether she wants to or not - or otherwise, when he throws her out because she doesn't comply, she will be the fallen woman and the one to blame, not him. Harshly said, having men rape you and give you crumbs of bread, or having men rape you and give you jewellry and fancy clothes, it's both awful.

And on one hand I agree, I'd rather be married to Dombey than being a prostitute, especially in the Victorian time where there were not any condoms or practically failsafe ways to protect yourself from pregnancy and diseases we have now. On the other hand, is having to sell your body for money, and having to allow men to have sex with you because society has taken all other options from you, not as bad for every woman? Sure, Edith has the security that she will have a roof over her head and food on the table at all times, not depending on how often Dombey wants to have sex. But if he wants to, she has to comply, wether she wants to or not - or otherwise, when he throws her out because she doesn't comply, she will be the fallen woman and the one to blame, not him. Harshly said, having men rape you and give you crumbs of bread, or having men rape you and give you jewellry and fancy clothes, it's both awful.

Yes. The role Edith plays in the novel and the reasons for that role offer many avenues of approach and analysis. She is a very fascinating character. And there is much more to come.

David wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because t..."

David

There are no dumb questions. More often than not, when anyone asks a question in our weekly discussions there will be more than one response and suggested direction the analysis could take.

After you have the opportunity to read a couple of novels you will pick up your own skills and interpretation approaches. The only comment I feel certain about is that Dickens will constantly surprise his readers. Indeed, for us who have read the novel more than once we find new, different, or contradictory ideas bubbling up to the surface all the time.

For instance, I have always approached Edith Granger is a similar fashion. This time around I am finding my previous opinions no longer satisfy me. The fun of a group is we are all in this together.

Just enjoy the process.

David

There are no dumb questions. More often than not, when anyone asks a question in our weekly discussions there will be more than one response and suggested direction the analysis could take.

After you have the opportunity to read a couple of novels you will pick up your own skills and interpretation approaches. The only comment I feel certain about is that Dickens will constantly surprise his readers. Indeed, for us who have read the novel more than once we find new, different, or contradictory ideas bubbling up to the surface all the time.

For instance, I have always approached Edith Granger is a similar fashion. This time around I am finding my previous opinions no longer satisfy me. The fun of a group is we are all in this together.

Just enjoy the process.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 33

Major events

At the beginning of the chapter, the narrator invites us to turn ”our eyes upon two homes” and he then proceeds to contrast the two homes: One is quite luxurious and boasts..."

In this chapter Dickens mentions feet that need tending and birds in large cages whose swing is like a wedding ring. What is Dickens up to in this chapter?

I agree with Tristram. The presentation of the two Carker homes gives us further insight into the brothers. What is it that James has? Well, he has a very well-appointed home with a picture that is somewhat like Edith Dombey in appearance. He has a large bird in a large cage and I think the description of the perch as being like a wedding ring is not by chance. We have just witnessed the Dombey-Granger wedding. It cannot be by chance that a portrait looks like Edith. Is it to remind us that Edith is herself now encased and trapped in a large house by virtue of her marriage to Dombey?

Dombey and Edith live in a magnificently renovated home in London and John lives in a much more humble home outside of London. John lives with his sister, and they live happily, if not richly. On the other hand, James Carker has wealth but no wife. He only has a bird in a cage. Of Dombey and John and James Carker, only James Carker does not have a person to share his life. While each man has his own distinct personality, James Carker lacks any human companionship. He only has a bird in a cage and a portrait on his wall. He has no form of human companionship at all.

And what about the mention of feet? If we go back to The Old Curiosity Shop we had a scene where a poor farmer’s wife washed and tended to the cut and bruised feet of Little Nell. In this novel we have Harriet Carker, in the “daily struggle of a poor existence” tendto the foot of Alice who said “what’s a torn foot in such as me, to such as you?” Harriet’s response was “let me give you something to bind it up.” Like in The Old Curiosity Shop where Nell and her father were fed by the poor farmer’s wife, we see Harriet giving the woman “fragments of her own frugal dinner.”

To me, these acts of washing and tending to another’s foot and feeding the poor reflects on the Bible and the washing of feet. In the Roman Catholic tradition the Pope symbolically washes other’s feet. Thus, the washing of feet is linked by association to an act of humility, kindness, and love. Harriet is a good person.

Earlier in the novel we had mention of feet as well. Florence’s shoe is kept by Walter and Mrs Tox pours water into her shoe when she is agitated. Could these other references to feet have a deeper meaning further on in the novel?

Major events

At the beginning of the chapter, the narrator invites us to turn ”our eyes upon two homes” and he then proceeds to contrast the two homes: One is quite luxurious and boasts..."

In this chapter Dickens mentions feet that need tending and birds in large cages whose swing is like a wedding ring. What is Dickens up to in this chapter?

I agree with Tristram. The presentation of the two Carker homes gives us further insight into the brothers. What is it that James has? Well, he has a very well-appointed home with a picture that is somewhat like Edith Dombey in appearance. He has a large bird in a large cage and I think the description of the perch as being like a wedding ring is not by chance. We have just witnessed the Dombey-Granger wedding. It cannot be by chance that a portrait looks like Edith. Is it to remind us that Edith is herself now encased and trapped in a large house by virtue of her marriage to Dombey?

Dombey and Edith live in a magnificently renovated home in London and John lives in a much more humble home outside of London. John lives with his sister, and they live happily, if not richly. On the other hand, James Carker has wealth but no wife. He only has a bird in a cage. Of Dombey and John and James Carker, only James Carker does not have a person to share his life. While each man has his own distinct personality, James Carker lacks any human companionship. He only has a bird in a cage and a portrait on his wall. He has no form of human companionship at all.

And what about the mention of feet? If we go back to The Old Curiosity Shop we had a scene where a poor farmer’s wife washed and tended to the cut and bruised feet of Little Nell. In this novel we have Harriet Carker, in the “daily struggle of a poor existence” tendto the foot of Alice who said “what’s a torn foot in such as me, to such as you?” Harriet’s response was “let me give you something to bind it up.” Like in The Old Curiosity Shop where Nell and her father were fed by the poor farmer’s wife, we see Harriet giving the woman “fragments of her own frugal dinner.”

To me, these acts of washing and tending to another’s foot and feeding the poor reflects on the Bible and the washing of feet. In the Roman Catholic tradition the Pope symbolically washes other’s feet. Thus, the washing of feet is linked by association to an act of humility, kindness, and love. Harriet is a good person.

Earlier in the novel we had mention of feet as well. Florence’s shoe is kept by Walter and Mrs Tox pours water into her shoe when she is agitated. Could these other references to feet have a deeper meaning further on in the novel?

Jantine wrote: "It is clear Alice has been a prostitute, all of her bitterness cirles around men looking at her body and judging her, while also using her. I think we can assume Carker the manager was the start of..."

Jantine wrote: "It is clear Alice has been a prostitute, all of her bitterness cirles around men looking at her body and judging her, while also using her. I think we can assume Carker the manager was the start of..."I agree that there are similarities between the two ways of selling yourself, but Edith went willingly into her arrangement and she did have a choice, however limited she felt her options were. Alice had to sell herself to strangers on a daily basis, but then I suppose this is the comparison that Dickens is making between the classes to which each belongs.

I'm really looking to seeing what happens with Alice, and how she deals with all three Carkers.

Tristram wrote: "Chapter 34

Major events

Chapter 34 reintroduces us to Good Mrs. Brown, who is sitting in an ugly, dark room somewhere in London and who is surprised by a female visitor that turns out to be her da..."

The presence of Alice and her mother and Edith and her mother in the novel reveal to us two possible roads that characters’ lives may take. Alice and Good Mrs Brown are gaining more traction in the plot of our novel. Dickens, as has been noted, has drawn our attention to both pairs of women in some subtle ways, but the concept of beautiful hair, as noted, creates both a curious and a physical link between Alice and Edith, and, by extension Florence. Good Mrs Brown has no trouble taking Florence’s clothes but would not cut her hair. What can be the links, if any?

Major events

Chapter 34 reintroduces us to Good Mrs. Brown, who is sitting in an ugly, dark room somewhere in London and who is surprised by a female visitor that turns out to be her da..."

The presence of Alice and her mother and Edith and her mother in the novel reveal to us two possible roads that characters’ lives may take. Alice and Good Mrs Brown are gaining more traction in the plot of our novel. Dickens, as has been noted, has drawn our attention to both pairs of women in some subtle ways, but the concept of beautiful hair, as noted, creates both a curious and a physical link between Alice and Edith, and, by extension Florence. Good Mrs Brown has no trouble taking Florence’s clothes but would not cut her hair. What can be the links, if any?

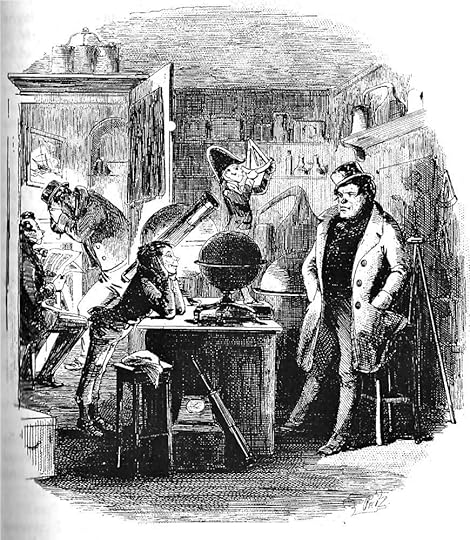

A Visitor of Distinction

Chapter 32

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘I say! I should like to speak a word to you, Mr Gills, if you please,’ said Toots at length, with surprising presence of mind. ‘I say! Miss D.O.M. you know!’

The Captain, with responsive gravity and mystery, immediately waved his hook towards the little parlour, whither Mr Toots followed him.

‘Oh! I beg your pardon though,’ said Mr Toots, looking up in the Captain’s face as he sat down in a chair by the fire, which the Captain placed for him; ‘you don’t happen to know the Chicken at all; do you, Mr Gills?’

‘The Chicken?’ said the Captain.

‘The Game Chicken,’ said Mr Toots.

The Captain shaking his head, Mr Toots explained that the man alluded to was the celebrated public character who had covered himself and his country with glory in his contest with the Nobby Shropshire One; but this piece of information did not appear to enlighten the Captain very much.

‘Because he’s outside: that’s all,’ said Mr Toots. ‘But it’s of no consequence; he won’t get very wet, perhaps.’

‘I can pass the word for him in a moment,’ said the Captain.

‘Well, if you would have the goodness to let him sit in the shop with your young man,’ chuckled Mr Toots, ‘I should be glad; because, you know, he’s easily offended, and the damp’s rather bad for his stamina. I’ll call him in, Mr Gills.’

With that, Mr Toots repairing to the shop-door, sent a peculiar whistle into the night, which produced a stoical gentleman in a shaggy white great-coat and a flat-brimmed hat, with very short hair, a broken nose, and a considerable tract of bare and sterile country behind each ear.

‘Sit down, Chicken,’ said Mr Toots.

The compliant Chicken spat out some small pieces of straw on which he was regaling himself, and took in a fresh supply from a reserve he carried in his hand.

‘There ain’t no drain of nothing short handy, is there?’ said the Chicken, generally. ‘This here sluicing night is hard lines to a man as lives on his condition.’

Captain Cuttle proffered a glass of rum, which the Chicken, throwing back his head, emptied into himself, as into a cask, after proposing the brief sentiment, ‘Towards us!’........

Mr Toots, with these words, shook the Captain’s hand; and disguising such traces of his agitation as could be disguised on so short a notice, before the Chicken’s penetrating glance, rejoined that eminent gentleman in the shop. The Chicken, who was apt to be jealous of his ascendancy, eyed Captain Cuttle with anything but favour as he took leave of Mr Toots, but followed his patron without being otherwise demonstrative of his ill-will: leaving the Captain oppressed with sorrow; and Rob the Grinder elevated with joy, on account of having had the honour of staring for nearly half an hour at the conqueror of the Nobby Shropshire One.

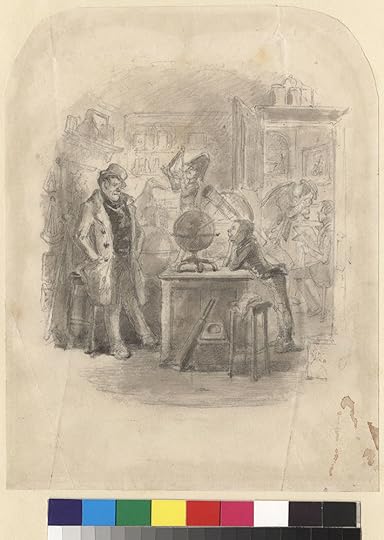

"Go," said the good-humoured manager

Chapter 32

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘Captain Cuttle,’ returned the Manager, with all possible politeness, ‘I must ask you to do me a favour.’

‘And what is it, Sir?’ inquired the Captain.

‘To have the goodness to walk off, if you please,’ rejoined the Manager, stretching forth his arm, ‘and to carry your jargon somewhere else.’

Every knob in the Captain’s face turned white with astonishment and indignation; even the red rim on his forehead faded, like a rainbow among the gathering clouds.

‘I tell you what, Captain Cuttle,’ said the Manager, shaking his forefinger at him, and showing him all his teeth, but still amiably smiling, ‘I was much too lenient with you when you came here before. You belong to an artful and audacious set of people. In my desire to save young what’s-his-name from being kicked out of this place, neck and crop, my good Captain, I tolerated you; but for once, and only once. Now, go, my friend!’

The Captain was absolutely rooted to the ground, and speechless—

‘Go,’ said the good-humoured Manager, gathering up his skirts, and standing astride upon the hearth-rug, ‘like a sensible fellow, and let us have no turning out, or any such violent measures. If Mr Dombey were here, Captain, you might be obliged to leave in a more ignominious manner, possibly. I merely say, Go!’

The Captain, laying his ponderous hand upon his chest, to assist himself in fetching a deep breath, looked at Mr Carker from head to foot, and looked round the little room, as if he did not clearly understand where he was, or in what company.

‘You are deep, Captain Cuttle,’ pursued Carker, with the easy and vivacious frankness of a man of the world who knew the world too well to be ruffled by any discovery of misdoing, when it did not immediately concern himself, ‘but you are not quite out of soundings, either—neither you nor your absent friend, Captain. What have you done with your absent friend, hey?’

Again the Captain laid his hand upon his chest. After drawing another deep breath, he conjured himself to ‘stand by!’ But in a whisper.

‘You hatch nice little plots, and hold nice little councils, and make nice little appointments, and receive nice little visitors, too, Captain, hey?’ said Carker, bending his brows upon him, without showing his teeth any the less: ‘but it’s a bold measure to come here afterwards. Not like your discretion! You conspirators, and hiders, and runners-away, should know better than that. Will you oblige me by going?’

‘My lad,’ gasped the Captain, in a choked and trembling voice, and with a curious action going on in the ponderous fist; ‘there’s a many words I could wish to say to you, but I don’t rightly know where they’re stowed just at present. My young friend, Wal’r, was drownded only last night, according to my reckoning, and it puts me out, you see. But you and me will come alongside o’one another again, my lad,’ said the Captain, holding up his hook, ‘if we live.’

‘It will be anything but shrewd in you, my good fellow, if we do,’ returned the Manager, with the same frankness; ‘for you may rely, I give you fair warning, upon my detecting and exposing you. I don’t pretend to be a more moral man than my neighbours, my good Captain; but the confidence of this House, or of any member of this House, is not to be abused and undermined while I have eyes and ears. Good day!’ said Mr Carker, nodding his head.

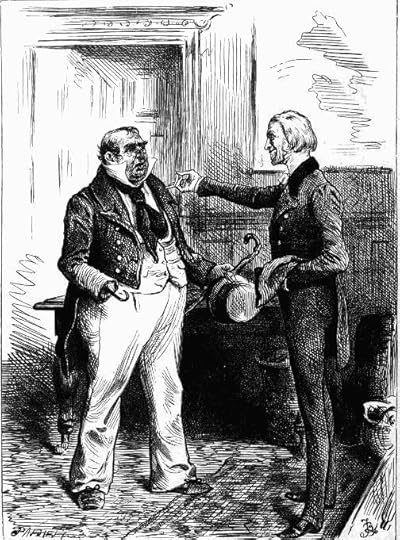

And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour

Chapter 32

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

The Captain reserved, until some fitter time, the consideration of Mr Toots’s offer of friendship, and thus dismissed him. Captain Cuttle’s spirits were so low, in truth, that he half determined, that day, to take no further precautions against surprise from Mrs MacStinger, but to abandon himself recklessly to chance, and be indifferent to what might happen. As evening came on, he fell into a better frame of mind, however; and spoke much of Walter to Rob the Grinder, whose attention and fidelity he likewise incidentally commended. Rob did not blush to hear the Captain earnest in his praises, but sat staring at him, and affecting to snivel with sympathy, and making a feint of being virtuous, and treasuring up every word he said (like a young spy as he was) with very promising deceit.

When Rob had turned in, and was fast asleep, the Captain trimmed the candle, put on his spectacles—he had felt it appropriate to take to spectacles on entering into the Instrument Trade, though his eyes were like a hawk’s—and opened the prayer-book at the Burial Service. And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour, and stopping now and then to wipe his eyes, the Captain, in a true and simple spirit, committed Walter’s body to the deep.

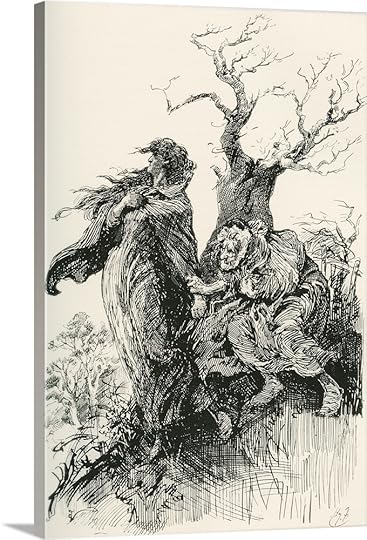

A certain skilful action of his fingers as he hummed some bars, and beat time on the seal beside him

Chapter 33

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Her pensive form was not long idle at the door. There was daily duty to discharge, and daily work to do—for such commonplace spirits that are not heroic, often work hard with their hands—and Harriet was soon busy with her household tasks. These discharged, and the poor house made quite neat and orderly, she counted her little stock of money, with an anxious face, and went out thoughtfully to buy some necessaries for their table, planning and conniving, as she went, how to save. So sordid are the lives of such low natures, who are not only not heroic to their valets and waiting-women, but have neither valets nor waiting-women to be heroic to withal!

While she was absent, and there was no one in the house, there approached it by a different way from that the brother had taken, a gentleman, a very little past his prime of life perhaps, but of a healthy florid hue, an upright presence, and a bright clear aspect, that was gracious and good-humoured. His eyebrows were still black, and so was much of his hair; the sprinkling of grey observable among the latter, graced the former very much, and showed his broad frank brow and honest eyes to great advantage.

After knocking once at the door, and obtaining no response, this gentleman sat down on a bench in the little porch to wait. A certain skilful action of his fingers as he hummed some bars, and beat time on the seat beside him, seemed to denote the musician; and the extraordinary satisfaction he derived from humming something very slow and long, which had no recognisable tune, seemed to denote that he was a scientific one.

The gentleman was still twirling a theme, which seemed to go round and round and round, and in and in and in, and to involve itself like a corkscrew twirled upon a table, without getting any nearer to anything, when Harriet appeared returning. He rose up as she advanced, and stood with his head uncovered.

‘You are come again, Sir!’ she said, faltering.

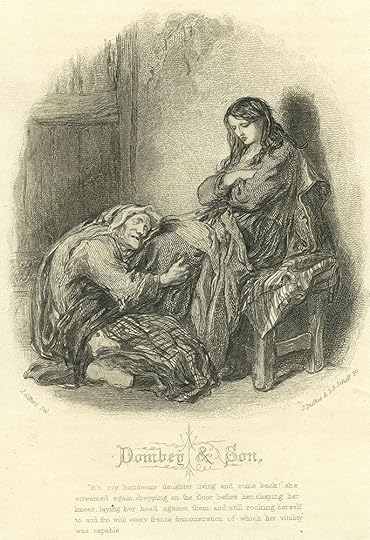

Alice Brown and her mother

Chapter 34

Sir John Gilbert

Text Illustrated:

The old woman, mumbling and shaking her head, and muttering to herself about her handsome daughter, brought a candle from a cupboard in the corner, and thrusting it into the fire with a trembling hand, lighted it with some difficulty and set it on the table. Its dirty wick burnt dimly at first, being choked in its own grease; and when the bleared eyes and failing sight of the old woman could distinguish anything by its light, her visitor was sitting with her arms folded, her eyes turned downwards, and a handkerchief she had worn upon her head lying on the table by her side.

"She sent to me by word of mouth then, my gal, Alice?" mumbled the old woman, after waiting for some moments. "What did she say?"

"Look," returned the visitor.

The old woman repeated the word in a scared uncertain way; and, shading her eyes, looked at the speaker, round the room, and at the speaker once again.

"Alice said look again, mother;" and the speaker fixed her eyes upon her.

Again the old woman looked round the room, and at her visitor, and round the room once more. Hastily seizing the candle, and rising from her seat, she held it to the visitor's face, uttered a loud cry, set down the light, and fell upon her neck!

"It's my gal! It's my Alice! It's my handsome daughter, living and come back!" screamed the old woman, rocking herself to and fro upon the breast that coldly suffered her embrace. "It's my gal! It's my Alice! It's my handsome daughter, living and come back!" she screamed again, dropping on the floor before her, clasping her knees, laying her head against them, and still rocking herself to and fro with every frantic demonstration of which her vitality was capable.

"Yes, mother," returned Alice, stooping forward for a moment and kissing her, but endeavoring, even in the act, to disengage herself from her embrace. "I am here, at last. Let go, mother; let go. Get up, and sit in your chair. What good does this do?"

Commentary:

John Gilbert, unlike his co-illustrator, Felix Octavius Carr Darley, focuses on the villainous James Carker's backstory rather than on the nautical characters associated with Walter Gay and Florence Dombey. The scene in the frontispiece for the third volume involves the reunion of a transported felon and her mother, Good Mrs. Brown, whom Dickens describes with imagery associated with witchcraft. As with the Household Edition illustration for the same chapter by Fred Barnard — "She's come back harder than she went!" cried the mother, looking up in her face, and still holding her knees, the effectiveness of the illustration depends upon the sharp contrast between the defiant, aloof, erect, beautiful young woman and decrepit, exhausted, grovelling crone, an iteration of the novel's col temp theme. The lengthy caption enables the reader to identify the passage as he or she comes to it, but not before since the frontispiece refers to neither page nor chapter:

"It's my handsome daughter, living and come back!" she screamed again, dropping on the floor before her, clasping her knees, laying her head against them, and still rocking herself to and fro with every frantic demonstration of which her vitality was capable.

A proleptic reading is not possible without some foreknowledge of James Carker's backstory and his betrayal of his mistress, Alice Marwood (the alias of Alice Brown, the young woman in the Gilbert frontispiece). These details, including Alice's uncanny resemblance to Edith Granger (whose uncle seduced Good Mrs. Brown), are provided in Chapters 33 and 34, which fall within the range of chapters (31 through 46) included in this third volume. The illustration is therefore significant in highlighting the importance of this subplot, which Dickens's original illustrator, 1847 engraving The Rejected Alms, which features Alice and her mother, left , and James Carker's older brother, John, and sister, Harriet, who live in a simple cottage outside London. Alice and her mother return Harriet's charity with disdain once they discover Harriet's relationship to James Carker. The cause of the antipathy is James's refusal to come to the aid of Alice and her mother, now living in a hovel with a leaky roof in the heart of east London. This, then, is the context of the scene depicted by Gilbert — although there is little of the vengeful and defiant rebel about the exhausted, dispirited young woman in Gilbert's illustration.

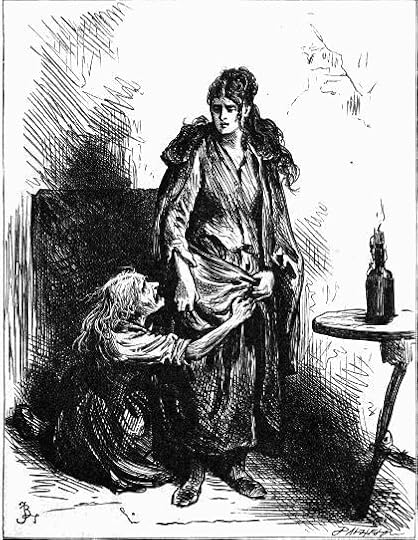

"She's come back harder than she went!"

Chapter 34

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘It’s my gal! It’s my Alice! It’s my handsome daughter, living and come back!’ screamed the old woman, rocking herself to and fro upon the breast that coldly suffered her embrace. ‘It’s my gal! It’s my Alice! It’s my handsome daughter, living and come back!’ she screamed again, dropping on the floor before her, clasping her knees, laying her head against them, and still rocking herself to and fro with every frantic demonstration of which her vitality was capable.

‘Yes, mother,’ returned Alice, stooping forward for a moment and kissing her, but endeavouring, even in the act, to disengage herself from her embrace. ‘I am here, at last. Let go, mother; let go. Get up, and sit in your chair. What good does this do?’

‘She’s come back harder than she went!’ cried the mother, looking up in her face, and still holding to her knees. ‘She don’t care for me! after all these years, and all the wretched life I’ve led!’

‘Why, mother!’ said Alice, shaking her ragged skirts to detach the old woman from them: ‘there are two sides to that. There have been years for me as well as you, and there has been wretchedness for me as well as you. Get up, get up!’

Her mother rose, and cried, and wrung her hands, and stood at a little distance gazing on her. Then she took the candle again, and going round her, surveyed her from head to foot, making a low moaning all the time. Then she put the candle down, resumed her chair, and beating her hands together to a kind of weary tune, and rolling herself from side to side, continued moaning and wailing to herself.

Alice got up, took off her wet cloak, and laid it aside. That done, she sat down as before, and with her arms folded, and her eyes gazing at the fire, remained silently listening with a contemptuous face to her old mother’s inarticulate complainings.

‘Did you expect to see me return as youthful as I went away, mother?’ she said at length, turning her eyes upon the old woman. ‘Did you think a foreign life, like mine, was good for good looks? One would believe so, to hear you!’

‘It ain’t that!’ cried the mother. ‘She knows it!’

‘What is it then?’ returned the daughter. ‘It had best be something that don’t last, mother, or my way out is easier than my way in.’

‘Hear that!’ exclaimed the mother. ‘After all these years she threatens to desert me in the moment of her coming back again!’

‘I tell you, mother, for the second time, there have been years for me as well as you,’ said Alice. ‘Come back harder? Of course I have come back harder. What else did you expect?’

‘Harder to me! To her own dear mother!’ cried the old woman

‘I don’t know who began to harden me, if my own dear mother didn’t,’ she returned, sitting with her folded arms, and knitted brows, and compressed lips as if she were bent on excluding, by force, every softer feeling from her breast. ‘Listen, mother, to a word or two. If we understand each other now, we shall not fall out any more, perhaps. I went away a girl, and have come back a woman. I went away undutiful enough, and have come back no better, you may swear. But have you been very dutiful to me?’

‘I!’ cried the old woman. ‘To my gal! A mother dutiful to her own child!’

‘It sounds unnatural, don’t it?’ returned the daughter, looking coldly on her with her stern, regardless, hardy, beautiful face; ‘but I have thought of it sometimes, in the course of my lone years, till I have got used to it. I have heard some talk about duty first and last; but it has always been of my duty to other people. I have wondered now and then—to pass away the time—whether no one ever owed any duty to me.’

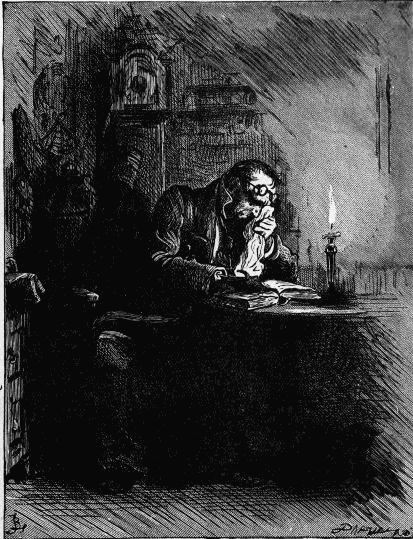

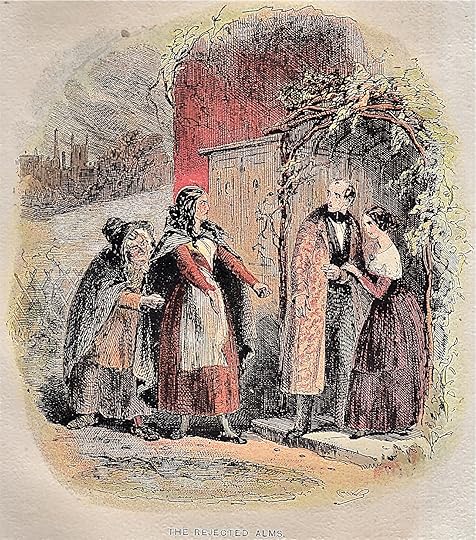

original sketch

The Rejected Alms

Chapter 34

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘I want your sister,’ she said. ‘The woman who gave me money to-day.’

At the sound of her raised voice, Harriet came out.

‘Oh!’ said Alice. ‘You are here! Do you remember me?’

‘Yes,’ she answered, wondering.

The face that had humbled itself before her, looked on her now with such invincible hatred and defiance; and the hand that had gently touched her arm, was clenched with such a show of evil purpose, as if it would gladly strangle her; that she drew close to her brother for protection.

‘That I could speak with you, and not know you! That I could come near you, and not feel what blood was running in your veins, by the tingling of my own!’ said Alice, with a menacing gesture.

‘What do you mean? What have I done?’

‘Done!’ returned the other. ‘You have sat me by your fire; you have given me food and money; you have bestowed your compassion on me! You! whose name I spit upon!’

The old woman, with a malevolence that made her ugliness quite awful, shook her withered hand at the brother and sister in confirmation of her daughter, but plucked her by the skirts again, nevertheless, imploring her to keep the money.

‘If I dropped a tear upon your hand, may it wither it up! If I spoke a gentle word in your hearing, may it deafen you! If I touched you with my lips, may the touch be poison to you! A curse upon this roof that gave me shelter! Sorrow and shame upon your head! Ruin upon all belonging to you!’

As she said the words, she threw the money down upon the ground, and spurned it with her foot.

‘I tread it in the dust: I wouldn’t take it if it paved my way to Heaven! I would the bleeding foot that brought me here to-day, had rotted off, before it led me to your house!’

Harriet, pale and trembling, restrained her brother, and suffered her to go on uninterrupted.

‘It was well that I should be pitied and forgiven by you, or anyone of your name, in the first hour of my return! It was well that you should act the kind good lady to me! I’ll thank you when I die; I’ll pray for you, and all your race, you may be sure!’

With a fierce action of her hand, as if she sprinkled hatred on the ground, and with it devoted those who were standing there to destruction, she looked up once at the black sky, and strode out into the wild night.

Kim wrote: "

And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour

Chapter 32

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

The Captain reserved, until some fitter time, the consideration of Mr Toots’s offer of frie..."

Ah Kim, this Barnard illustration is really good. It is unadorned, bleak, and the character of Cuttle perfectly imagined. There can be no doubt of Cuttle’s feelings towards Walter, and, by extension, the reader Is drawn into more sympathy for Walter as well.

And reading softly to himself, in the little back parlour

Chapter 32

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

The Captain reserved, until some fitter time, the consideration of Mr Toots’s offer of frie..."

Ah Kim, this Barnard illustration is really good. It is unadorned, bleak, and the character of Cuttle perfectly imagined. There can be no doubt of Cuttle’s feelings towards Walter, and, by extension, the reader Is drawn into more sympathy for Walter as well.

Kim wrote: "

"She's come back harder than she went!"

Chapter 34

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘It’s my gal! It’s my Alice! It’s my handsome daughter, living and come back!’ screamed the old woman, rockin..."

This scene, one of the most powerful and revealing of the novel, is captured perfectly by Barnard. Once again, it is apparent that Barnard is portraying the text with sensitivity and insight. Gasp, dare I say that in these chapters Barnard is the equal of ( or even better) than Browne?

"She's come back harder than she went!"

Chapter 34

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘It’s my gal! It’s my Alice! It’s my handsome daughter, living and come back!’ screamed the old woman, rockin..."

This scene, one of the most powerful and revealing of the novel, is captured perfectly by Barnard. Once again, it is apparent that Barnard is portraying the text with sensitivity and insight. Gasp, dare I say that in these chapters Barnard is the equal of ( or even better) than Browne?

Peter wrote: "Ah Kim, this Barnard illustration is really good. "

Peter wrote: "Ah Kim, this Barnard illustration is really good. "It is a wonderful drawing - it is so evocative, and captures the feeling of the moment exactly.

The revelations of Kim's are game-changers though - the seductions and betrayals !

Although I'm a bit unclear who Edith's uncle is/was. Should I know this at this point ?

My kindle edition of the book doesn't have any illustrations in, so I really appreciate Kim's hard work :-)

Kim wrote: "

original sketch

The Rejected Alms

Chapter 34

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘I want your sister,’ she said. ‘The woman who gave me money to-day.’

At the sound of her raised voice, Harriet came o..."

This illustration lets the reader know the bitterness that exists between the name Carker and Alice and her mother. Just consider how a few hours earlier Harriet Carker had fed Alice and tended to her injured foot.

Browne’s illustration is very emblematic. Harriet and John Carker stand in their doorway, and an arch of vegetation covers their heads. The Carker’s stand on their door stoop. In contrast, Alice and Good Mrs Brown stand on the dirt road. Behind them in the illustration is a fence. Most significantly, the left foot of both Alice and Good Mrs Brown extends in front of them and points directly towards James and Harriet Carker.

In the accompanying text we read that Alice throws the money Harriet gave her on the dusty ground “and spurned it with her foot.” Alice continues “I would the bleeding foot that brought me here today, had rotted off ...” Alice’s hatred goes to “anyone of your name.” Thus, there is a connection between the name Carker and Alice.

The text and the picture combine to create much curiosity and wonder in the reader’s mind.

original sketch

The Rejected Alms

Chapter 34

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

‘I want your sister,’ she said. ‘The woman who gave me money to-day.’

At the sound of her raised voice, Harriet came o..."

This illustration lets the reader know the bitterness that exists between the name Carker and Alice and her mother. Just consider how a few hours earlier Harriet Carker had fed Alice and tended to her injured foot.

Browne’s illustration is very emblematic. Harriet and John Carker stand in their doorway, and an arch of vegetation covers their heads. The Carker’s stand on their door stoop. In contrast, Alice and Good Mrs Brown stand on the dirt road. Behind them in the illustration is a fence. Most significantly, the left foot of both Alice and Good Mrs Brown extends in front of them and points directly towards James and Harriet Carker.

In the accompanying text we read that Alice throws the money Harriet gave her on the dusty ground “and spurned it with her foot.” Alice continues “I would the bleeding foot that brought me here today, had rotted off ...” Alice’s hatred goes to “anyone of your name.” Thus, there is a connection between the name Carker and Alice.

The text and the picture combine to create much curiosity and wonder in the reader’s mind.

David wrote: "Peter wrote: "Ah Kim, this Barnard illustration is really good. "

It is a wonderful drawing - it is so evocative, and captures the feeling of the moment exactly.

The revelations of Kim's are gam..."

Hi David

I’m glad you are enjoying the illustrations that Kim provides each week.

As to your question regarding the connection between Edith and other characters in the novel. There have been hints, and part of the joy of Dickens is unravelling the connections among the various characters. For now, know you are right. Edith may well be connected to others in the novel. Can we leave it at that for now?

:-]

It is a wonderful drawing - it is so evocative, and captures the feeling of the moment exactly.

The revelations of Kim's are gam..."

Hi David

I’m glad you are enjoying the illustrations that Kim provides each week.

As to your question regarding the connection between Edith and other characters in the novel. There have been hints, and part of the joy of Dickens is unravelling the connections among the various characters. For now, know you are right. Edith may well be connected to others in the novel. Can we leave it at that for now?

:-]

David wrote: "Jantine wrote: "Alice's pride is the opposite of that, it hardens her to an extent that she throws anyone and everyone under the bus, and rather suffers than think kindly of someone, only because t..."

David,

As Peter said I also think that there are no dumb questions, least of all in connections with Victorian novels, which were written in a time that has many facets we can no longer understand easily. I had in mind that Alice became a prostitute, probably after she had become Carker's mistress and then been cast off by him. In those days, women often did not have a lot of choices after being discarded as a mistress - they were often disowned by their families even and had to see how to scrape together what they needed for a living. Trollope's novel The Vicar of Bullhampton, for example, also gives insight into this problem.

David,

As Peter said I also think that there are no dumb questions, least of all in connections with Victorian novels, which were written in a time that has many facets we can no longer understand easily. I had in mind that Alice became a prostitute, probably after she had become Carker's mistress and then been cast off by him. In those days, women often did not have a lot of choices after being discarded as a mistress - they were often disowned by their families even and had to see how to scrape together what they needed for a living. Trollope's novel The Vicar of Bullhampton, for example, also gives insight into this problem.

Peter wrote: "While each man has his own distinct personality, James Carker lacks any human companionship. He only has a bird in a cage and a portrait on his wall. He has no form of human companionship at all."

He also has a flower-garden which he never enters but which he keeps as Harriet has left it, whereas pretty much everything else has been altered in James Carker's house. This little detail shows that even Mr. Carker has a soft spot because he will not completely forget the memory of his once beloved sister, although he clearly loves her no longer. The narrator also tells us that he lost his love for her because of what he considers "an ungrateful slight" dealt to him by her, namely her loyalty to her other brother.

Feeling slighted by the sister's adherence to her other brother surely has something to do with jealousy, and jealousy links Carker to Mr. Dombey himself, who is jealous of everyone that had the affection of little Paul - jealousy enhances Dombey's dislike for his own daughter and it also resolves him to send off Walter. This nasty character trait also links Carker to the Major, whose spiteful behaviour towards Miss Tox is rooted in jealousy since he could not bear playing second fiddle to Dombey and his son in Miss Tox's private life.

And jealousy, or the feeling of being slighted, is not too far away from pride, which is another major theme of the novel. So inserting this detail of the flower-garden not only helps Dickens to make his villain a little bit more complex by giving him a soft spot, a trace of humaneness, but it also links him to the other rather negative characters in the book.

He also has a flower-garden which he never enters but which he keeps as Harriet has left it, whereas pretty much everything else has been altered in James Carker's house. This little detail shows that even Mr. Carker has a soft spot because he will not completely forget the memory of his once beloved sister, although he clearly loves her no longer. The narrator also tells us that he lost his love for her because of what he considers "an ungrateful slight" dealt to him by her, namely her loyalty to her other brother.

Feeling slighted by the sister's adherence to her other brother surely has something to do with jealousy, and jealousy links Carker to Mr. Dombey himself, who is jealous of everyone that had the affection of little Paul - jealousy enhances Dombey's dislike for his own daughter and it also resolves him to send off Walter. This nasty character trait also links Carker to the Major, whose spiteful behaviour towards Miss Tox is rooted in jealousy since he could not bear playing second fiddle to Dombey and his son in Miss Tox's private life.

And jealousy, or the feeling of being slighted, is not too far away from pride, which is another major theme of the novel. So inserting this detail of the flower-garden not only helps Dickens to make his villain a little bit more complex by giving him a soft spot, a trace of humaneness, but it also links him to the other rather negative characters in the book.

David wrote: "I agree that there are similarities between the two ways of selling yourself, but Edith went willingly into her arrangement and she did have a choice, however limited she felt her options were. Alice had to sell herself to strangers on a daily basis ..."