The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Dombey and Son

Dombey and Son

>

D&S, Chp. 42-45

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 43

The narration now leads us back to Florence and to the impressions the recent events have made on her: Florence wants to know how her father is, but whenever the Nipper asks at the door, she is waved off by Mrs. Pipchin. It is only at night that Florence can dare to creep to her father’s room, as of old, and see if Mrs. Pipchin is still on guard. Luckily for Floy, the venerable lady has dozed off, and so she can steal into her father’s room and watch the sleeping man’s first. For the first time, she sees her father’s features without the shade of displeasure that her presence usually calls forth in them, and when I read this, I was struck with the sadness of the thought that a child should never have seen their parent’s face without any clear sign of emotional rejection. Florence hardly dares to touch her father’s face or arm for fear of waking him up and destroying this rare moment of tenderness and fulfilment of her love. Neither does she dare to stay there very long, and when she withdraws, she comes across her stepmother, and falls asleep, after a long night of watching and worrying, on Edith’s bed.

Thoughts and Questions

I sometimes find myself asking how Florence manages to keep up her love for a man who so utterly disregards her and fends her off with coldness and disdain. Is it not more likely that rebuffed love will eventually die and turn to indifference or even antipathy? How much meekness and tenderness of heart does it take to keep such love alive?

The chapter starts with some reflexions of Florence’s about her unhappy situation at home, and the narrator says that luckily, she is unaware of the fact that the gulf between her father and Edith is widened by the love Edith shows for her and which her father notices to his displeasure. Florence sometimes has qualms about her feelings for Edith because in a way she wonders whether they cannot be seen as some kind of disloyalty towards her own father. Yet, she cannot help wondering whether it might not have been her father’s similar treatment of her own mother that made the poor woman pine away and die prematurely. – Surely, thoughts like that would torment anyone but to a young woman like Florence, who has no one else and thus must bear them on her own, these thoughts are a living hell.

We also learn that Susan Nipper, although glad to find that Edith is not as proud and disdainful to Florence as to anyone else, feels some pangs of jealousy because of the good relationship the new Mrs. Dombey has with Florence, and so, ”Miss Nipper looked on […] at domestic affairs in general, with a resolute conviction that no good would come of Mrs Dombey.” – All too human, isn’t it?

There is one particular that strikes me as interesting in the scene between Florence and Edith here, and that is when Edith cries, a score of times, “’Don’t leave me! be near me! I have no hope but in you!’” – Why might Edith feel that way about Florence?

The narration now leads us back to Florence and to the impressions the recent events have made on her: Florence wants to know how her father is, but whenever the Nipper asks at the door, she is waved off by Mrs. Pipchin. It is only at night that Florence can dare to creep to her father’s room, as of old, and see if Mrs. Pipchin is still on guard. Luckily for Floy, the venerable lady has dozed off, and so she can steal into her father’s room and watch the sleeping man’s first. For the first time, she sees her father’s features without the shade of displeasure that her presence usually calls forth in them, and when I read this, I was struck with the sadness of the thought that a child should never have seen their parent’s face without any clear sign of emotional rejection. Florence hardly dares to touch her father’s face or arm for fear of waking him up and destroying this rare moment of tenderness and fulfilment of her love. Neither does she dare to stay there very long, and when she withdraws, she comes across her stepmother, and falls asleep, after a long night of watching and worrying, on Edith’s bed.

Thoughts and Questions

I sometimes find myself asking how Florence manages to keep up her love for a man who so utterly disregards her and fends her off with coldness and disdain. Is it not more likely that rebuffed love will eventually die and turn to indifference or even antipathy? How much meekness and tenderness of heart does it take to keep such love alive?

The chapter starts with some reflexions of Florence’s about her unhappy situation at home, and the narrator says that luckily, she is unaware of the fact that the gulf between her father and Edith is widened by the love Edith shows for her and which her father notices to his displeasure. Florence sometimes has qualms about her feelings for Edith because in a way she wonders whether they cannot be seen as some kind of disloyalty towards her own father. Yet, she cannot help wondering whether it might not have been her father’s similar treatment of her own mother that made the poor woman pine away and die prematurely. – Surely, thoughts like that would torment anyone but to a young woman like Florence, who has no one else and thus must bear them on her own, these thoughts are a living hell.

We also learn that Susan Nipper, although glad to find that Edith is not as proud and disdainful to Florence as to anyone else, feels some pangs of jealousy because of the good relationship the new Mrs. Dombey has with Florence, and so, ”Miss Nipper looked on […] at domestic affairs in general, with a resolute conviction that no good would come of Mrs Dombey.” – All too human, isn’t it?

There is one particular that strikes me as interesting in the scene between Florence and Edith here, and that is when Edith cries, a score of times, “’Don’t leave me! be near me! I have no hope but in you!’” – Why might Edith feel that way about Florence?

Chapter 44

This chapter has some comic relief – when, the next morning, Susan Nipper decides to walk into Mr. Dombey’s room and to give him a piece of her mind on his way of treating Florence and of keeping his own daughter away from him, and that paragon of pride and dignity hardly knows what’s coming to him –, but it also moves the story farther into darkness because the upshot of Susan’s brave foray is her dismissal from Dombey’s household, which leaves Florence all the more isolated and friendless. Mrs. Pipchin is apparently all too glad to get rid of the “hussy” and “slut” she sees in the Nipper, and the Nipper may be broken-hearted but she would never let it on in Mrs. Pipchin’s presence, and instead of waiting the whole month she has been given notice of, she decides to quit at once, for fear of making it even more difficult for her to part from Florence the longer she waits. Luckily, Mr. Toots drops by that fateful morning, and he takes care of Susan, regaling her with a breakfast before the young woman heads off for her brother’s place. – Mr. Toots makes use of this unhoped-for and prolonged interview with the Nipper to ask whether there is any use for him to hope that Florence might love him one day, and Susan’s answer … well, it’s of no consequence. Apart from that, Mr. Toots has another problem: He would like to get rid of the Game Chicken, and that worthy man, sensing it, is willing to push up the price for going away by making himself as disagreeable as he probably can.

Thoughts and questions

The Nipper’s curtain lecture to Mr. Dombey: A comic highlight beyond any doubt – I loved her “and how I dare I know not but I do!” and the complete absence of punctuation in her speech sometimes –, and the Nipper will doubtless have voiced our own thoughts, but apart from that, Susan and Florence have a high price to pay for that brief moment of venting her spleen. Did Susan really think that she could have changed Dombey’s mind? That she could have done Florence any good? Or was it just an instance of flying off the handle? And did she know it would cost her her position in the house?

Did you also have the impression that Dombey was out of his element when Susan told him her mind? He couldn’t do anything but ask his servants for help – so much was his dignity endangered by any direct encounter with the Nipper. And he kept calling her “woman” as though he didn’t reven remember her name, which he probably really didn’t. What impression did you get of Dombey here?

Susan also says, “’[…] there ain’t no gentleman, no Sir, though as great and rich as all the greatest and richest of England put together, but might be proud of her and would and ought. If he knew her value right, he’d rather lose his greatness and his fortune piece by piece and beg his way in rags from door to door, I say to some and all, he would!’” – Maybe, Mr. Dombey should watch out?

I also have the impression that Florence’s days in the house will get harder; now even Mrs. Pipchin can accuse her, to her father, of having spoiled Susan and thereby encouraged her to such an act of insubordination.

Last not least, do you think that Mr. Toots will come to terms with the hopelessness of his position as Florence’s suitor? And if so, how will he soothe himself?

This chapter has some comic relief – when, the next morning, Susan Nipper decides to walk into Mr. Dombey’s room and to give him a piece of her mind on his way of treating Florence and of keeping his own daughter away from him, and that paragon of pride and dignity hardly knows what’s coming to him –, but it also moves the story farther into darkness because the upshot of Susan’s brave foray is her dismissal from Dombey’s household, which leaves Florence all the more isolated and friendless. Mrs. Pipchin is apparently all too glad to get rid of the “hussy” and “slut” she sees in the Nipper, and the Nipper may be broken-hearted but she would never let it on in Mrs. Pipchin’s presence, and instead of waiting the whole month she has been given notice of, she decides to quit at once, for fear of making it even more difficult for her to part from Florence the longer she waits. Luckily, Mr. Toots drops by that fateful morning, and he takes care of Susan, regaling her with a breakfast before the young woman heads off for her brother’s place. – Mr. Toots makes use of this unhoped-for and prolonged interview with the Nipper to ask whether there is any use for him to hope that Florence might love him one day, and Susan’s answer … well, it’s of no consequence. Apart from that, Mr. Toots has another problem: He would like to get rid of the Game Chicken, and that worthy man, sensing it, is willing to push up the price for going away by making himself as disagreeable as he probably can.

Thoughts and questions

The Nipper’s curtain lecture to Mr. Dombey: A comic highlight beyond any doubt – I loved her “and how I dare I know not but I do!” and the complete absence of punctuation in her speech sometimes –, and the Nipper will doubtless have voiced our own thoughts, but apart from that, Susan and Florence have a high price to pay for that brief moment of venting her spleen. Did Susan really think that she could have changed Dombey’s mind? That she could have done Florence any good? Or was it just an instance of flying off the handle? And did she know it would cost her her position in the house?

Did you also have the impression that Dombey was out of his element when Susan told him her mind? He couldn’t do anything but ask his servants for help – so much was his dignity endangered by any direct encounter with the Nipper. And he kept calling her “woman” as though he didn’t reven remember her name, which he probably really didn’t. What impression did you get of Dombey here?

Susan also says, “’[…] there ain’t no gentleman, no Sir, though as great and rich as all the greatest and richest of England put together, but might be proud of her and would and ought. If he knew her value right, he’d rather lose his greatness and his fortune piece by piece and beg his way in rags from door to door, I say to some and all, he would!’” – Maybe, Mr. Dombey should watch out?

I also have the impression that Florence’s days in the house will get harder; now even Mrs. Pipchin can accuse her, to her father, of having spoiled Susan and thereby encouraged her to such an act of insubordination.

Last not least, do you think that Mr. Toots will come to terms with the hopelessness of his position as Florence’s suitor? And if so, how will he soothe himself?

Chapter 45

Our last chapter this week is called The Trusty Agent and is, of course, about Mr. Carker once again. Now, I generally like Dickens’s villains quite a lot – Jonas Chuzzlewit is repellent, but fascinating; Uriah Heep gives me a pleasure-laden shudder like a figure from a horror movie; I can understand Bradley Headstone’s destructive passion, and Ralph Nickleby is a perfect stage villain – but Mr. Carker is getting on my nerves and makes me really feel uneasy at the same time. And yet, there definitely are people like he around, scheming, hypocritical, ruthless scoundrels, but he lacks the glamour and the quirks of many another Dickens villain, doesn’t he?

Our chapter is basically about the next encounter between Carker and Edith, and by now, the latter seems to have resigned herself to Mr. Carker’s constant presence and his private interviews with her although she still keeps up a façade of proud resistance and scorn. In this interview, we witness Carker spinning his web around Mrs. Dombey, indirectly threatening that it may depend upon him whether or not Florence’s position in the Dombey household might get incredibly worse, and that it also depends on the understanding between himself and Mrs. Dombey. He nudges Edith into some kind of partnership, speaking of how glad he is that he finally has her “confidence” and thus makes her side (with him) against her husband, although he avoids committing himself fully. All in all, Edith’s own position is getting more and more shaky in the course of this interview, and it almost leaves Carker and her in some kind of conspiracy against Dombey – his insistence on once more taking (and kissing) her hand (mind that she no longer bruises it after the deed) speaks volumes and shows the ascendancy he has gained over her.

Thoughts and questions

In some other thread I recently said that the name Dombey makes me think of the word “donkey” (and the animal as well), and so I had to smile when I came across these words of Carker:

In a way, Carker manages to put Dombey’s character into a nutshell, which shows what an astute observer and analyst he is. We also learn that he is apparently piqued at the lack of consideration his employer shows towards him and his feelings as a man when he makes him fulfil the odious task as a go-between with regard to Edith. To me, it is clear that Carker’s attentions have clearly swerved from Florence to Edith, that he is utterly infatuated with his employer’s wife and that he no longer entertains any desire to marry into the family and the firm via Florence – but that he is simply moved by his sensuous fascination with Edith. He is still a schemer, but no longer a cold one, bent on money and influence; instead, he is a passionate one, who is still obsessed with power – just look at the chapter’s final paragraph – but mainly with lust.

Our last chapter this week is called The Trusty Agent and is, of course, about Mr. Carker once again. Now, I generally like Dickens’s villains quite a lot – Jonas Chuzzlewit is repellent, but fascinating; Uriah Heep gives me a pleasure-laden shudder like a figure from a horror movie; I can understand Bradley Headstone’s destructive passion, and Ralph Nickleby is a perfect stage villain – but Mr. Carker is getting on my nerves and makes me really feel uneasy at the same time. And yet, there definitely are people like he around, scheming, hypocritical, ruthless scoundrels, but he lacks the glamour and the quirks of many another Dickens villain, doesn’t he?

Our chapter is basically about the next encounter between Carker and Edith, and by now, the latter seems to have resigned herself to Mr. Carker’s constant presence and his private interviews with her although she still keeps up a façade of proud resistance and scorn. In this interview, we witness Carker spinning his web around Mrs. Dombey, indirectly threatening that it may depend upon him whether or not Florence’s position in the Dombey household might get incredibly worse, and that it also depends on the understanding between himself and Mrs. Dombey. He nudges Edith into some kind of partnership, speaking of how glad he is that he finally has her “confidence” and thus makes her side (with him) against her husband, although he avoids committing himself fully. All in all, Edith’s own position is getting more and more shaky in the course of this interview, and it almost leaves Carker and her in some kind of conspiracy against Dombey – his insistence on once more taking (and kissing) her hand (mind that she no longer bruises it after the deed) speaks volumes and shows the ascendancy he has gained over her.

Thoughts and questions

In some other thread I recently said that the name Dombey makes me think of the word “donkey” (and the animal as well), and so I had to smile when I came across these words of Carker:

”’[…] You did not know how exacting and how proud he is, or how he is, if I may say so, the slave of his own greatness, and goes yoked to his own triumphal car like a beast of burden, with no idea on earth but that it is behind him and is to be drawn on, over everything and through everything.’”

In a way, Carker manages to put Dombey’s character into a nutshell, which shows what an astute observer and analyst he is. We also learn that he is apparently piqued at the lack of consideration his employer shows towards him and his feelings as a man when he makes him fulfil the odious task as a go-between with regard to Edith. To me, it is clear that Carker’s attentions have clearly swerved from Florence to Edith, that he is utterly infatuated with his employer’s wife and that he no longer entertains any desire to marry into the family and the firm via Florence – but that he is simply moved by his sensuous fascination with Edith. He is still a schemer, but no longer a cold one, bent on money and influence; instead, he is a passionate one, who is still obsessed with power – just look at the chapter’s final paragraph – but mainly with lust.

Tristram

Your final question of Chapter 42 which is “why was the parrot of Carker’s swinging so wildly in its wedding ring” is answered in Chapter 45. I agree that Carker has moved from simply being Dombey’s agent and contact with Edith to her handler and her controller. A metaphor that shows this new power hierarchy is the caged bird and repeated references to a bird’s feathers. Edith is the caged bird. A facsimile of Edith may appear in a portrait on Carker’s wall but her body is represented by the caged bird swinging on a wedding ring.

In Chapter 45, “The Trusty Agent,” Carker confronts Edith. During this interview Edith “plucked the feathers from a pinion of some rare and beautiful bird, which hung from her wrist by a golden thread, to serve as a fan, and rained them on the ground.” Without its pinions, a bird cannot fly. Later, under more scrutiny from Carker, we read that Carker “saw the soft down tremble once again, and he saw her lay her plumage of the beautiful bird against her bosom for a moment; and he unfolded one more ring of the coil into which he had gathered himself.” The last sentence shows us one final glimpse of Edith. She has been cornered, captured, and apparently defeated by Carker. At home, Carker remembers how “the white down had fluttered; how the bird’s feathers had been strewn upon the ground.” Carker, the cat, has trapped his prey, Edith Dombey. The feathers and down of her pinion have rained down and now lay, like Edith’s former imperious character, “upon the ground.”

In Chapter 42 Carker had kissed Florence’s hand, an act that made Edith strike and injure her hand against the chimney. In this chapter Carker kisses Edith's maimed hand. This I see as the final transference of Carker’s designs on Florence to that of Edith. When Carker left the house “he waved the hand with which he had taken hers, and thrust it in his breast.” The action of thrusting his hand I believe has sexual connotations. Carker’s designs on Edith are not to simply dominate her but to possess her sexually as well.

Your final question of Chapter 42 which is “why was the parrot of Carker’s swinging so wildly in its wedding ring” is answered in Chapter 45. I agree that Carker has moved from simply being Dombey’s agent and contact with Edith to her handler and her controller. A metaphor that shows this new power hierarchy is the caged bird and repeated references to a bird’s feathers. Edith is the caged bird. A facsimile of Edith may appear in a portrait on Carker’s wall but her body is represented by the caged bird swinging on a wedding ring.

In Chapter 45, “The Trusty Agent,” Carker confronts Edith. During this interview Edith “plucked the feathers from a pinion of some rare and beautiful bird, which hung from her wrist by a golden thread, to serve as a fan, and rained them on the ground.” Without its pinions, a bird cannot fly. Later, under more scrutiny from Carker, we read that Carker “saw the soft down tremble once again, and he saw her lay her plumage of the beautiful bird against her bosom for a moment; and he unfolded one more ring of the coil into which he had gathered himself.” The last sentence shows us one final glimpse of Edith. She has been cornered, captured, and apparently defeated by Carker. At home, Carker remembers how “the white down had fluttered; how the bird’s feathers had been strewn upon the ground.” Carker, the cat, has trapped his prey, Edith Dombey. The feathers and down of her pinion have rained down and now lay, like Edith’s former imperious character, “upon the ground.”

In Chapter 42 Carker had kissed Florence’s hand, an act that made Edith strike and injure her hand against the chimney. In this chapter Carker kisses Edith's maimed hand. This I see as the final transference of Carker’s designs on Florence to that of Edith. When Carker left the house “he waved the hand with which he had taken hers, and thrust it in his breast.” The action of thrusting his hand I believe has sexual connotations. Carker’s designs on Edith are not to simply dominate her but to possess her sexually as well.

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Dombey surely has a way of hurting people’s feelings through utter, arrogant disregard, hasn’t he?."

Tristram wrote: "Mr. Dombey surely has a way of hurting people’s feelings through utter, arrogant disregard, hasn’t he?."My question is, who's more hateful, Dombey or Carker? Sure Dombey is more stupid and so maybe deserves more benefit of the doubt than calculating Carker, but he's crossed a line here with his treatment of Florence and obvious desire to make Edith as unhappy as he possibly can. I'd say at this point he's an equal partner in evil with Carker. They are clearly co-enablers.

So anyway, lots to hate here. But I'm probably going to give in and read ahead because the tension is pretty unbearable. Will Florence make it out of this? Will Edith fall further? Will Susan and Toots and Diogenes save the day? When is Walter coming back, and what unlikely explanation will cover his return? What truly twisted end has Dickens got in mind for Carker? Who will end up whose secret relative or long-lost lover? So many Dickensian balls in the air!

Julie wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Mr. Dombey surely has a way of hurting people’s feelings through utter, arrogant disregard, hasn’t he?."

My question is, who's more hateful, Dombey or Carker? Sure Dombey is more ..."

Hi Julie

D&S is a delight to read and I loved your phrase that there were many balls in the air. So many questions. It’s at times like these I best appreciate how the serialization format of publishing is so great.

My question is, who's more hateful, Dombey or Carker? Sure Dombey is more ..."

Hi Julie

D&S is a delight to read and I loved your phrase that there were many balls in the air. So many questions. It’s at times like these I best appreciate how the serialization format of publishing is so great.

I feel the same as Julie. On one hand I was slightly behind (lots of books to read that I could only read for a set time, like library books and Netgalley books, so I had a lot to read), on the other hand every time I finish the week's installment I want to read on! So many balls in the air, and I notice that I am very much invested in the characters. Especially Florence, but Edith too, and I love Nipper and Toots, and truly dislike Carker and Dombey. I keep wondering if the Chicken ends up playing a part in helping either Floy/Edith or Dombey/Carker as well. He is mentioned so many times together with Toots, that I feel he might be some undercover plotter against Carker or something like that.

I love how you all point out the symbolism between Carker and Edith. I had the feeling before that at least his power over her sexually aroused him, and probably Edith herself as well, and I couldn't put my finger upon what gave it away. You did that for me though. So thanks! And did anyone else notice that Dombey was very adamant that his letting Carker be the messenger was not a punishment to her from his end, but a way to get the message across better because he felt it wouldn't if he delivered the message himself - and then Carker turned it arount in chapter 45, telling Edith it was very much meant as a punishment, and Dombey told him so. While Dombey very much crossed that line for me too, I could not help but thing what an a**hole Carker was for playing Dombey and Edith against each other even more for his own gains.

I'm very, very curious how things will go from here. I too believe Floy's life will be even more horrid after this, when she loses both the Nipper and as far as she knows Edith at the same time. Will she survive all this? Or was it a foreshadowing that if she knew about how Edith's love for her widened the gap between her father and her would be her death? She will probably find out now, won't she?

I love how you all point out the symbolism between Carker and Edith. I had the feeling before that at least his power over her sexually aroused him, and probably Edith herself as well, and I couldn't put my finger upon what gave it away. You did that for me though. So thanks! And did anyone else notice that Dombey was very adamant that his letting Carker be the messenger was not a punishment to her from his end, but a way to get the message across better because he felt it wouldn't if he delivered the message himself - and then Carker turned it arount in chapter 45, telling Edith it was very much meant as a punishment, and Dombey told him so. While Dombey very much crossed that line for me too, I could not help but thing what an a**hole Carker was for playing Dombey and Edith against each other even more for his own gains.

I'm very, very curious how things will go from here. I too believe Floy's life will be even more horrid after this, when she loses both the Nipper and as far as she knows Edith at the same time. Will she survive all this? Or was it a foreshadowing that if she knew about how Edith's love for her widened the gap between her father and her would be her death? She will probably find out now, won't she?

Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him getting thrown off the horse is symbolic that he is not in control of the situation.

Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him getting thrown off the horse is symbolic that he is not in control of the situation.I love how Susan Nipper told Dombey off, but too bad she's forced to leave! I thought it was humorous when Dombey kept trying to reach for the bell, but couldn't and pulled his own hair just to have something to pull. Good show of frustration there.

Poor Florence has lost another friend. However, this could be an opportunity for her to wise up. I do think her pining for her father is unrealistic at this point and should have turned to anger, apathy, or even just acceptance by now. She's a budding young woman who should be thinking about her own future.

Carker kissing Edith's hand seems symbolic too, like maybe the kiss transferred some of his slyness to her which will help her defeat Dombey's pride in the future. Carker's quote about Dombey being a beast of burden pulling his own pride was excellent imagery and very on point!

Alissa wrote: "Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him getting thrown off the horse is symbolic that he is not in control of the situation...."

Alissa wrote: "Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him getting thrown off the horse is symbolic that he is not in control of the situation...."Alissa, that's such a good point that after I read it, I went back to see just exactly how the fall is described, which I think tightens the symbolism you point to even more:

Mr Dombey, in his dignity, rode with very long stirrups, and a very loose rein, and very rarely deigned to look down to see where his horse went.

But here's Carker's riding: "quick of eye, steady of hand, and a good horseman."

Oops, I don't think there were any spoilers in it, but I just realized (I have indeed been cheating and reading ahead) that I made a reference belonging to the next section of the book, so I deleted it. Apologies!

Oops, I don't think there were any spoilers in it, but I just realized (I have indeed been cheating and reading ahead) that I made a reference belonging to the next section of the book, so I deleted it. Apologies!

Julie wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him g..."

Julie wrote: "Alissa wrote: "Dombey is quite a control freak, wanting to control Edith AND her relationship with Florence. Yet, Dombey seldom gets what he wants. He seems powerless in many regards. I think him g..."Thanks for digging up that imagery, Julie. :-) I missed it the first time. Dombey's "loose rein" versus Carker's "steady hand" says a lot about who is in control.

It looks like Dombey's stiffness is not an advantage on a horse, or in life. The flexible, feline Carker has the advantage here.

Julie and Alissa

Thank you for pointing out and pursuing the connections and horsemanship of Dombey and Carker. Your comments are very illuminating and point out what I have consistently missed in my earlier readings of the book.

I started thinking further about Carker on his horse as portrayed by Hablot Browne. In Chapter 24 we see Carker greeting Florence and the Skettles while on his horse. As mentioned previously, in the background of the illustration we see various animals and birds - representing the natural world - in a state of fright or flight. On his horse in the foreground, we see Carker has a firm grasp of the reins and his horse is in a position of head-down submission. I never thought about what was right in front of my eyes. Thanks.

Thank you for pointing out and pursuing the connections and horsemanship of Dombey and Carker. Your comments are very illuminating and point out what I have consistently missed in my earlier readings of the book.

I started thinking further about Carker on his horse as portrayed by Hablot Browne. In Chapter 24 we see Carker greeting Florence and the Skettles while on his horse. As mentioned previously, in the background of the illustration we see various animals and birds - representing the natural world - in a state of fright or flight. On his horse in the foreground, we see Carker has a firm grasp of the reins and his horse is in a position of head-down submission. I never thought about what was right in front of my eyes. Thanks.

When we take a closer look at Dombey right now, we find that he is not a good rider, being too stiff and full of himself, that he is not good at playing cards or other games - probably being too dull - and that he is not very good at communicating his ideas to other people. What also strikes me is that we have never really seen him in his counting-house and we may assume from that that he is not really actively involved with his business, is he? Alissa and Julie pointed out that he is not watching out where his horse is going. What if his business is also some kind of horse? It would be too brazen to compare his marriage with a horse, but well ...

Alissa wrote: "I love how Susan Nipper told Dombey off, but too bad she's forced to leave! I thought it was humorous when Dombey kept trying to reach for the bell, but couldn't and pulled his own hair just to have something to pull. Good show of frustration there."

Yes, Dombey's pulling at his own hair just because he cannot reach the bellstring is a good show of frustration. And also one of helplessness and ridicule - he is simply not used to doing things on his own but just orders other people around, and therefore when push comes to shove he will depend on other people doing things for him.

Another thought came to me: His pride renders Dombey ridiculous but more in a deplorable than a truly entertaining way. May we therefore not say that excessive pride is the most boring variety of dumbness?

Yes, Dombey's pulling at his own hair just because he cannot reach the bellstring is a good show of frustration. And also one of helplessness and ridicule - he is simply not used to doing things on his own but just orders other people around, and therefore when push comes to shove he will depend on other people doing things for him.

Another thought came to me: His pride renders Dombey ridiculous but more in a deplorable than a truly entertaining way. May we therefore not say that excessive pride is the most boring variety of dumbness?

Alissa wrote: "Poor Florence has lost another friend. However, this could be an opportunity for her to wise up. I do think her pining for her father is unrealistic at this point and should have turned to anger, apathy, or even just acceptance by now. She's a budding young woman who should be thinking about her own future."

Yes, you are talking from the bottom of my heart here, Alissa. But it's probably that those Dickens heroines just have to be self-forebearing and ready to make an eternal sacrifice of themselves. Many another person would just fly off their handle at this juncture, but Florence simply doesn't.

Yes, you are talking from the bottom of my heart here, Alissa. But it's probably that those Dickens heroines just have to be self-forebearing and ready to make an eternal sacrifice of themselves. Many another person would just fly off their handle at this juncture, but Florence simply doesn't.

Tristram wrote: "When we take a closer look at Dombey right now, we find that he is not a good rider, being too stiff and full of himself, that he is not good at playing cards or other games - probably being too dull - and that he is not very good at communicating his ideas to other people. What also strikes me is that we have never really seen him in his counting-house and we may assume from that that he is not really actively involved with his business, is he?"

Tristram wrote: "When we take a closer look at Dombey right now, we find that he is not a good rider, being too stiff and full of himself, that he is not good at playing cards or other games - probably being too dull - and that he is not very good at communicating his ideas to other people. What also strikes me is that we have never really seen him in his counting-house and we may assume from that that he is not really actively involved with his business, is he?"It makes you wonder what exactly he does do all day.

Hi guys, WARNING! The last few days my head has hurt so much that there is no guarantee these illustrations are all the ones there are. Why am I in such a condition? I know you are dying to know. I don't know if you remember the group of people I talk about at times that meet here at our home on Wednesday evenings, well Wednesdays that we aren't singing at nursing homes. Obviously we haven't been singing at nursing homes, and I have no idea when we will be able to again because of the virus. And we haven't been meeting at all because most of the people in our group are older people that were originally in our church choir and had no where to go when we stopped having a church choir, so they come here. Well one of those members has the coronavirus and I've been worried about her, then on Tuesday the phone rang and one of our members had died that day, only it was a different member and I was not expecting it at all. I can barely walk into our living room because I see the rocking chair that he sat on every week for six years now and I find myself crying all over again. Then yesterday our Pastor called and asked if I would play the piano for the funeral, the family would like me to play because of our friendship, they don't even want an organist, only me which makes me smile just thinking of it, and makes me cry just thinking of it, and now I am crying all over again. Anyway, I'm going through music now trying to pick what I want to play at the funeral, something I've never had to do before and hope I never have to do again, and needed a break, so here are the illustrations. The ones that were easy to find anyway. Sorry for the long introduction to them.

[image error]

original sketch

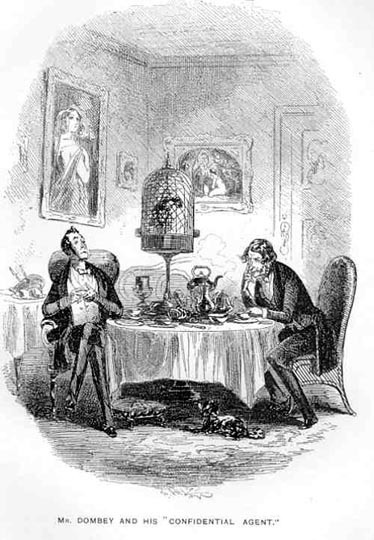

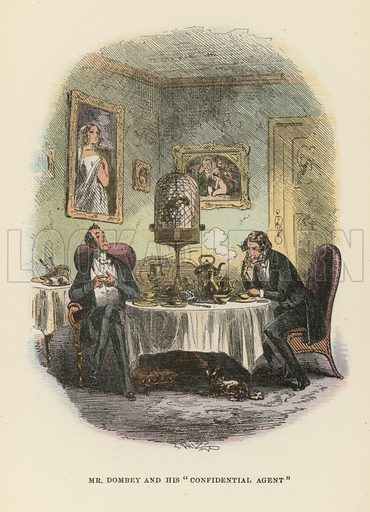

Mr. Dombey and his confidential agent

Chapter 42

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

He directed a sharp glance and a sharp smile at Mr Dombey as he spoke, and a sharper glance, and a sharper smile yet, when Mr Dombey, drawing himself up before the fire, in the attitude so often copied by his second in command, looked round at the pictures on the walls. Cursorily as his cold eye wandered over them, Carker’s keen glance accompanied his, and kept pace with his, marking exactly where it went, and what it saw. As it rested on one picture in particular, Carker hardly seemed to breathe, his sidelong scrutiny was so cat-like and vigilant, but the eye of his great chief passed from that, as from the others, and appeared no more impressed by it than by the rest.

Carker looked at it—it was the picture that resembled Edith—as if it were a living thing; and with a wicked, silent laugh upon his face, that seemed in part addressed to it, though it was all derisive of the great man standing so unconscious beside him. Breakfast was soon set upon the table; and, inviting Mr Dombey to a chair which had its back towards this picture, he took his own seat opposite to it as usual.

Mr Dombey was even graver than it was his custom to be, and quite silent. The parrot, swinging in the gilded hoop within her gaudy cage, attempted in vain to attract notice, for Carker was too observant of his visitor to heed her; and the visitor, abstracted in meditation, looked fixedly, not to say sullenly, over his stiff neckcloth, without raising his eyes from the table-cloth. As to Rob, who was in attendance, all his faculties and energies were so locked up in observation of his master, that he scarcely ventured to give shelter to the thought that the visitor was the great gentleman before whom he had been carried as a certificate of the family health, in his childhood, and to whom he had been indebted for his leather smalls.

Commentary:

The plate "Mr. Dombey and his 'confidential agent"' (ch. 42), is of special interest for the care with which Browne sets forth visually the drift of Dickens' text. Carker regards covertly the painting on the wall which happens to resemble Edith; but Browne has added another painting depicting a seminude woman at her outdoor bath. A close look (particularly at Steel B) reveals at left the head of a man who is evidently watching the bathing woman; the most likely allusion is to Actaeon coming upon Diana at her bath. (Phiz used this allusion twice, with more graphic clarity but less emblematic significance, in Lever's The Daltons.) Another apparent contribution of Browne's is the small dog near Carker's feet; since it is a lapdog, looking up at Dombey with its tongue out, it seems to function as an emblem of Carker himself, fawning upon his master; consistent with this emblem, Carker's teeth are here concealed, while in all previous plates they are very much in evidence.

[image error]

original sketch

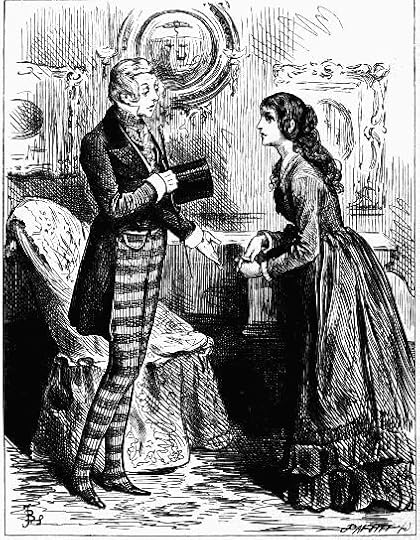

Florence parts from a very old friend

Chapter 44

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

The object of her regret was not long in coming to her, for the news soon spread over the house that Susan Nipper had had a disturbance with Mrs Pipchin, and that they had both appealed to Mr Dombey, and that there had been an unprecedented piece of work in Mr Dombey’s room, and that Susan was going. The latter part of this confused rumour, Florence found to be so correct, that Susan had locked the last trunk and was sitting upon it with her bonnet on, when she came into her room.

‘Susan!’ cried Florence. ‘Going to leave me! You!’

‘Oh for goodness gracious sake, Miss Floy,’ said Susan, sobbing, ‘don’t speak a word to me or I shall demean myself before them Pi-i-pchinses, and I wouldn’t have ‘em see me cry Miss Floy for worlds!’

‘Susan!’ said Florence. ‘My dear girl, my old friend! What shall I do without you! Can you bear to go away so?’

‘No-n-o-o, my darling dear Miss Floy, I can’t indeed,’ sobbed Susan. ‘But it can’t be helped, I’ve done my duty, Miss, I have indeed. It’s no fault of mine. I am quite resigned. I couldn’t stay my month or I could never leave you then my darling and I must at last as well as at first, don’t speak to me Miss Floy, for though I’m pretty firm I’m not a marble doorpost, my own dear.’

‘What is it? Why is it?’ said Florence, ‘Won’t you tell me?’ For Susan was shaking her head.

‘No-n-no, my darling,’ returned Susan. ‘Don’t ask me, for I mustn’t, and whatever you do don’t put in a word for me to stop, for it couldn’t be and you’d only wrong yourself, and so God bless you my own precious and forgive me any harm I have done, or any temper I have showed in all these many years!’

With which entreaty, very heartily delivered, Susan hugged her mistress in her arms.

‘My darling there’s a many that may come to serve you and be glad to serve you and who’ll serve you well and true,’ said Susan, ‘but there can’t be one who’ll serve you so affectionate as me or love you half as dearly, that’s my comfort. Go-ood-bye, sweet Miss Floy!’

Do you call it managing this establishment, madam," said Mr. Dombey, "to leave a person like this at liberty to come and talk to me!"

Chaptr 44

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

‘Why, hoity toity!’ cried the voice of Mrs Pipchin, as the black bombazeen garments of that fair Peruvian Miner swept into the room. ‘What’s this, indeed?’

Susan favoured Mrs Pipchin with a look she had invented expressly for her when they first became acquainted, and resigned the reply to Mr Dombey.

‘What’s this?’ repeated Mr Dombey, almost foaming. ‘What’s this, Madam? You who are at the head of this household, and bound to keep it in order, have reason to inquire. Do you know this woman?’

‘I know very little good of her, Sir,’ croaked Mrs Pipchin. ‘How dare you come here, you hussy? Go along with you!’

But the inflexible Nipper, merely honouring Mrs Pipchin with another look, remained.

‘Do you call it managing this establishment, Madam,’ said Mr Dombey, ‘to leave a person like this at liberty to come and talk to me! A gentleman—in his own house—in his own room—assailed with the impertinences of women-servants!’

‘Well, Sir,’ returned Mrs Pipchin, with vengeance in her hard grey eye, ‘I exceedingly deplore it; nothing can be more irregular; nothing can be more out of all bounds and reason; but I regret to say, Sir, that this young woman is quite beyond control. She has been spoiled by Miss Dombey, and is amenable to nobody. You know you’re not,’ said Mrs Pipchin, sharply, and shaking her head at Susan Nipper. ‘For shame, you hussy! Go along with you!’

‘If you find people in my service who are not to be controlled, Mrs Pipchin,’ said Mr Dombey, turning back towards the fire, ‘you know what to do with them, I presume. You know what you are here for? Take her away!’

"Miss Dombey," returned Mr. Toots, "If you'll only name one, you'll - you'll give me an appetite."

Chapter 44

Fred Barnard

Text Illustrated:

Quick as thought, Florence glided out and hastened downstairs, where Mr Toots, in the most splendid vestments, was breathing very hard with doubt and agitation on the subject of her coming.

‘Oh, how de do, Miss Dombey,’ said Mr Toots, ‘God bless my soul!’

This last ejaculation was occasioned by Mr Toots’s deep concern at the distress he saw in Florence’s face; which caused him to stop short in a fit of chuckles, and become an image of despair.

‘Dear Mr Toots,’ said Florence, ‘you are so friendly to me, and so honest, that I am sure I may ask a favour of you.’

‘Miss Dombey,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘if you’ll only name one, you’ll—you’ll give me an appetite. To which,’ said Mr Toots, with some sentiment, ‘I have long been a stranger.’

‘Susan, who is an old friend of mine, the oldest friend I have,’ said Florence, ‘is about to leave here suddenly, and quite alone, poor girl. She is going home, a little way into the country. Might I ask you to take care of her until she is in the coach?’

‘Miss Dombey,’ returned Mr Toots, ‘you really do me an honour and a kindness. This proof of your confidence, after the manner in which I was Beast enough to conduct myself at Brighton—’

‘Yes,’ said Florence, hurriedly—‘no—don’t think of that. Then would you have the kindness to—to go? and to be ready to meet her when she comes out? Thank you a thousand times! You ease my mind so much. She doesn’t seem so desolate. You cannot think how grateful I feel to you, or what a good friend I am sure you are!’ and Florence in her earnestness thanked him again and again; and Mr Toots, in his earnestness, hurried away—but backwards, that he might lose no glimpse of her.

Florence had not the courage to go out, when she saw poor Susan in the hall, with Mrs Pipchin driving her forth, and Diogenes jumping about her, and terrifying Mrs Pipchin to the last degree by making snaps at her bombazeen skirts, and howling with anguish at the sound of her voice—for the good duenna was the dearest and most cherished aversion of his breast. But she saw Susan shake hands with the servants all round, and turn once to look at her old home; and she saw Diogenes bound out after the cab, and want to follow it, and testify an impossibility of conviction that he had no longer any property in the fare; and the door was shut, and the hurry over, and her tears flowed fast for the loss of an old friend, whom no one could replace. No one. No one.

Kim

First, I am so sorry to read you are in such pain and sorrow. Please know that all Curiosities send you our sympathy and love. Take care.

First, I am so sorry to read you are in such pain and sorrow. Please know that all Curiosities send you our sympathy and love. Take care.

Kim wrote: "

Dombey and Carker

Phiz"

Browne and his partner Young did several individual portraits of characters from Dombey and Son. They were released and sold separately from the novel’s illustrations that appeared in the monthly instalments. This illustration is one of the “extra” portraits. The extra illustrations of Browne were larger in format. All featured individual characters rather than groups of many people or places.

If anyone is interested in seeing any of the extra illustrations let me know.

Dombey and Carker

Phiz"

Browne and his partner Young did several individual portraits of characters from Dombey and Son. They were released and sold separately from the novel’s illustrations that appeared in the monthly instalments. This illustration is one of the “extra” portraits. The extra illustrations of Browne were larger in format. All featured individual characters rather than groups of many people or places.

If anyone is interested in seeing any of the extra illustrations let me know.

Kim wrote: "

original sketch

Mr. Dombey and his confidential agent

Chapter 42

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

He directed a sharp glance and a sharp smile at Mr Dombey as he spoke, and a sharper glance, and a ..."

This illustration is effective in both its composition and use of emblems. The bird cage is in the centre of the illustration. From the text we know that the caged bird is perched on its “wedding ring” swing. The characters of Dombey and Carker are found on different sides of the cage. Dombey’s pose is imperious; Carker leans forward in apparent attention to Dombey’s presence.

As noted in the text a portrait of a person who resembles Edith is on the wall behind Dombey’s back. This suggests that Dombey is ignoring Edith. Carker faces Dombey, and, of course, the Edith-like portrait. The text illustration commentary of message 20 points out the emblematic nature of the picture on Carker’s wall depicting Actaeon and Diana. Browne’s addition of the lapdog not mentioned in the text is perfect emblem which asks a question to the reader about the relationship between Dombey and Carker. Between Carker and Dombey, who really is the lapdog of the other?

original sketch

Mr. Dombey and his confidential agent

Chapter 42

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

He directed a sharp glance and a sharp smile at Mr Dombey as he spoke, and a sharper glance, and a ..."

This illustration is effective in both its composition and use of emblems. The bird cage is in the centre of the illustration. From the text we know that the caged bird is perched on its “wedding ring” swing. The characters of Dombey and Carker are found on different sides of the cage. Dombey’s pose is imperious; Carker leans forward in apparent attention to Dombey’s presence.

As noted in the text a portrait of a person who resembles Edith is on the wall behind Dombey’s back. This suggests that Dombey is ignoring Edith. Carker faces Dombey, and, of course, the Edith-like portrait. The text illustration commentary of message 20 points out the emblematic nature of the picture on Carker’s wall depicting Actaeon and Diana. Browne’s addition of the lapdog not mentioned in the text is perfect emblem which asks a question to the reader about the relationship between Dombey and Carker. Between Carker and Dombey, who really is the lapdog of the other?

Kim wrote: "Hi guys, WARNING! The last few days my head has hurt so much that there is no guarantee these illustrations are all the ones there are. Why am I in such a condition? I know you are dying to know. I..."

Kim wrote: "Hi guys, WARNING! The last few days my head has hurt so much that there is no guarantee these illustrations are all the ones there are. Why am I in such a condition? I know you are dying to know. I..."I'm so sorry, Kim. And the family is fortunate to have a friend like you to play music for them.

Kim wrote: "Hi guys, WARNING! The last few days my head has hurt so much that there is no guarantee these illustrations are all the ones there are. Why am I in such a condition? I know you are dying to know. I..."

Kim,

I am very sorry to hear about your friend's having passed away. And like Julie, I'd say the family will appreciate your playing the music a lot and take comfort out of it, and I am also quite sure it will give comfort to you. I sincerely hope that the lady in your choir who has got the virus will recover soon.

All the best to you!

Kim,

I am very sorry to hear about your friend's having passed away. And like Julie, I'd say the family will appreciate your playing the music a lot and take comfort out of it, and I am also quite sure it will give comfort to you. I sincerely hope that the lady in your choir who has got the virus will recover soon.

All the best to you!

Kim wrote: "Hi guys, WARNING! The last few days my head has hurt so much that there is no guarantee these illustrations are all the ones there are. Why am I in such a condition? I know you are dying to know. I..."

I'm so sorry, Kim. Take care. Big hugs from here.

I'm so sorry, Kim. Take care. Big hugs from here.

Thank you everyone, I will talk to you all later, but I see the phone is ringing and that it is the Pastor of the church, hopefully not with another death. :-)

Spring has arrived in all its glory, but this year Covid is casting its shadow over everything although I must say that in my part of Germany, life is slowly going back to normal. In my hometown, we have not had any new infections since Saturday, and at the moment there are only 15 acute cases (out of roughly 330,000,000 inhabitants). I hope that wherever you live, things are brightening up as well!

Dombey and Son has given me a lot of enjoyment during the past few weeks and I am more and more captivated by this wonderful novel. So, let’s have a look at Chapter 42, which is entitled Confidential and Accidental.

What happens

After leaving the services of Captain Cuttle, Rob the Grinder has officially enlisted with Mr. Carker, but although he is treated to a new livery and probably better wages, Rob’s position is not very enviable because his life at Mr. Carker’s is one of constant intimidation and fear. Even when he makes his first appearance in front of Carker, the Manager submits him to some sadistic power play, claiming that he never asked him to give up his place at Cuttle’s in favour of a place with him, and although that is a blatant lie, Rob has not the heart to justify himself. I don’t pity the Grinder at all, but still there is the question why Mr. Carker makes him go through all this charade – have you got any ideas?

But Mr. Carker does not long show his bullying side because his boss, Mr. Dombey, is paying him a visit, and therefore he swiftly glides back into his feline and submissive manner. Dombey shows some mild interest in how Mr. Carker has embellished his own home, and then he and Carker sit down to breakfast in Carker’s room, where Mr. Dombey has the portrait of the Edith-like woman in his back. The painting may have struck Dombey, but he does not show a particular degree of bewilderment or impression but chooses to ignore it. In the course of their breakfast Dombey tells Carker that he is utterly dissatisfied with his wife’s behaviour – not only with her extravagance, but most of all with her lack of respect for and deference to him, things he deems himself entitled to. He even tells his inferior of the private conversation he and Edith had in her boudoir and how he has apparently cowed her for a moment. Nevertheless, as Mr. Dombey thinks, Edith has not fully comprehended her new position and its duties and that is why Dombey feels it incumbent on him to make sure that she will get to know her place. Observing the embarrassment she felt when he once made remonstrances to her in Carker’s presence, Mr. Dombey, not desirous of any further direct intercourse with his wife on that question, is determined to use Carker as a go-between with regard to himself and Edith. He does not mince his words – a proud man like him would not feel this necessary in the presence of a dependent – but adds that he partly chose Carker because he observed how painful it was to his wife when Carker witnessed their first quarrel.

Dombey also says that the major communication Carker has to make is that he is no longer willing to have Edith show particular regard for Florence because the contrast between the indifference Edith shows to him and the warmth she reserves for his daughter puts him in a bad light. Implicitly, he says that he might remove Florence from his household, were Edith to continue her special attentions to her step-daughter.

After this conversation, Carker and Dombey get on their horses to ride to Mr. Dombey’s offices, but on their way, Dombey’s horse throws him off and but for Mr. Carker’s interference, he would probably have died. Dombey, after spending the day at an inn under the attendance of some surgeons, is taken to his house in the evening, where Mrs. Pipchin, newly arrived from Brighton, acts as a Cerberus to the door of his sickroom, letting nobody in. Mr. Carker brings the news of Dombey’s accident to Edith, who has just come home. In the course of their short interview, Carker takes Edith’s hand and kisses it, which causes the lady, as soon as Carker has taken his leave, to savagely beat that hand on a marble-shelf, severely bruising it.

Thoughts and Questions

Rob the Grinder, for all his fear of Carker, clearly admires his new master, and the narrator tells us that Rob looks at Carker ”with the uneasiness which a cur will often manifest in a similar situation” – what does this tell us about him and the way he grew up? What criticism might the author have intended here?

During their interview, Carker watches every move and facial expression of his superior, especially when Mr. Dombey takes in the picture of the lady. – What might Carker’s intentions be in showing him that picture, which he could easily have hidden since he knew that Dombey would come to see him? Can you see through the game that man is playing? He even seems to be saying to himself, in some moments of their conversation, ”’Now, see, how I will lead him on’’” Where is he leading him to?

In another situation, Carker, in his flattering way, says that ”’[…] still I have that spontaneous interest in everything belonging to you […]’”. I would say this is quite ironical because it can be read as an indirect hint of Carker that he is interested in Edith, or in Dombey – and this knack of throwing out words that can be understood in two ways reminds me of the way a cat will play with a mouse.

On the other hand, is it necessary for us to regard Dombey as a victim? After all, in his interview he does not show any consideration for his dependant, and he even tells him that he chose him for the task as a go-between because Edith is not particularly fond of Carker. Mr. Dombey surely has a way of hurting people’s feelings through utter, arrogant disregard, hasn’t he? He simply assumes that Carker is well-rewarded by having his own regard and need not worry about what impression he leaves on Edith. Dombey compares the first Mrs. Dombey to the second, finding that the first, ”’[…] like any other lady in her place would […]’” has always adapted herself to his wishes. Carker quickly throws in the question whether Miss Dombey is like her mother in that respect, and throws Dombey off his balance here.

All in all, what impression does this conversation between the proud and inflexible man and the feline schemer create on you?

Sometimes, being thrown off a horse does not mean more than being thrown of a horse, but in the context of the whole novel – what significance might Mr. Dombey’s accident have? Could it be some kind of foreshadowing? By the way, it reminded me of a similar scene in our last novel – when Montague Tiggs lay under the hoofs of a horse, and Jonas was nearby.

Mr. Dombey says, ”’[…] You will please to tell her that her show of devotion for my daughter is disagreeable to me. It is likely to be noticed. […]’” What does this last sentence tell us about Mr. Dombey? Do you think that public opinion is the only thing that makes Edith’s warmth towards Florence unpalatable to Dombey, or may there be another reason?

And last not least, why was that parrot of Carker’s swinging so wildly in its wedding ring?