The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities

>

Book II, Chp. 14-18

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

In these chapters we are in both Paris and London. I agree that the funeral of Cly has all the hallmarks of what a grander revolution may well exhibit. Now, where is Cly, where is his body? Has he been recalled to life for some reason that will be explained later in the text? There is humour in the discovery that the coffin does not contain a body, but the humour is an uneasy one. Gone is the humour found in the earlier novels.

Mme Defarge’s knitting of names and calling her work a shroud is unsettling. Did anyone else think there are shades of reference to the The Three Fates of mythology in her description?

Doctor Manette’s psychological regression to his past and the physical manifestions of it seen in his return to his activity of a shoemaker tells us something major has happened to unhinge his mental stability. Lucie believes has heard the footsteps of hundreds of people coming to disrupt her tranquil life in London. Carton has warned her - and the reader - that such sounds cannot be good. Now, we have Doctor Manette again taking up the profession of a shoemaker. Shoes, sounds, a man who appears to have risen from the grave, a crowd that was on the verge of losing control in the streets.

I imagine the original readers of this book were on the edges of their chairs, just as we are.

Mme Defarge’s knitting of names and calling her work a shroud is unsettling. Did anyone else think there are shades of reference to the The Three Fates of mythology in her description?

Doctor Manette’s psychological regression to his past and the physical manifestions of it seen in his return to his activity of a shoemaker tells us something major has happened to unhinge his mental stability. Lucie believes has heard the footsteps of hundreds of people coming to disrupt her tranquil life in London. Carton has warned her - and the reader - that such sounds cannot be good. Now, we have Doctor Manette again taking up the profession of a shoemaker. Shoes, sounds, a man who appears to have risen from the grave, a crowd that was on the verge of losing control in the streets.

I imagine the original readers of this book were on the edges of their chairs, just as we are.

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of the narrator’s light and comic treatment of domestic violence at the Crunchers’? Did Dickens really play this kind of thing for humour? ..."

Tristram wrote: "What do you think of the narrator’s light and comic treatment of domestic violence at the Crunchers’? Did Dickens really play this kind of thing for humour? ..."Yeah, I think he did. This has been fodder for comedy until very recently, though in recent decades they never showed the abuse, they just found it funny to threaten it. Think of Jackie Gleason's, "One of these days, Alice... POW! Right in the kisser!" Or Ricky Ricardo looming menacingly over Lucy, who backs her way behind a chair to put a barrier between them. I listened to a podcast about an old TV show a couple of weeks ago, and the 30 somethings on the show were APPALLED at the sexism. Well, two things - first the whole point of the episode was to shine a light on the sexism and make it less acceptable, so it was actually a good thing. But, second - the show in question was from the early 60s. I don't think younger people have a clue as to how much differently things like this were seen just a very short time ago.

the mender of roads

the mender of roadsWhat an odd moniker. I was reminded, just phonetically, of the Colossus of Rhodes, which I really knew nothing about. Having looked it up, I don't really see anything symbolic that would relate to our story. Maybe it's just a coincidence, or is there something in the story of Helios? Sun god, sun king? Something about protecting the city? Am I searching for a connection that isn't there?

This statement (copied above from Tristam) reminds me of Les Miserables and the revolutionary scenes of that novel.

This statement (copied above from Tristam) reminds me of Les Miserables and the revolutionary scenes of that novel."Another darkness was closing in as surely, when the church bells, then ringing pleasantly in many an airy steeple over France, should be melted into thundering cannon; when the military drums should be beating to drown a wretched voice, that night all potent as the voice of Power and Plenty, Freedom and Life."

Does Mme DeFarge represent France itself?

Very interesting observations about the glimpses of mob mentality foreshadowing the revolution to come. I hadn't picked up on it, of course, but, as always, appreciate these connections when they're pointed out to me. :-)

Very interesting observations about the glimpses of mob mentality foreshadowing the revolution to come. I hadn't picked up on it, of course, but, as always, appreciate these connections when they're pointed out to me. :-)

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What do you think of the narrator’s light and comic treatment of domestic violence at the Crunchers’? Did Dickens really play this kind of thing for humour? ..."

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What do you think of the narrator’s light and comic treatment of domestic violence at the Crunchers’? Did Dickens really play this kind of thing for humour? ..."Yeah, I think he ..."

Yes, I think so too. It's very Punch and Judy. I'm glad that kind of thing doesn't go over as well now as it used to. Banging her head against the back of the bed--I don't think even at the time this could have come off as that funny if it were not so conventional that readers didn't really think about it as a real thing.

Still, I don't think Elizabeth Gaskell would have done this.

Tristram wrote: "We also learn that Mme Defarge’s knitting has a special purpose, namely that she is actually knitting a kind of black book by putting the names of people who are to be punished during the coming revolution – Mme Defarge tells her husband that a revolution will come even if they themselves will not necessarily live to see it –into the fabric, using a secret writing. That’s why, when asked what she is knitting, she meaningfully replies, “Shrouds"."

Tristram wrote: "We also learn that Mme Defarge’s knitting has a special purpose, namely that she is actually knitting a kind of black book by putting the names of people who are to be punished during the coming revolution – Mme Defarge tells her husband that a revolution will come even if they themselves will not necessarily live to see it –into the fabric, using a secret writing. That’s why, when asked what she is knitting, she meaningfully replies, “Shrouds"."Then again (building on the Cruncher discussion), I guess I have my own angle of maybe-inappropriate humor, because I found this little interchange between "composed" Madame D and a nosy bystander to be hilarious. Don't go small-talking with Madame Defarge, people! She is not a casual kind of person.

“I am highly gratified,” said Mr. Lorry, “....Dear me! This is an occasion that makes a man speculate on all he has lost. Dear, dear, dear! To think that there might have been a Mrs. Lorry, any time these fifty years almost!”

“I am highly gratified,” said Mr. Lorry, “....Dear me! This is an occasion that makes a man speculate on all he has lost. Dear, dear, dear! To think that there might have been a Mrs. Lorry, any time these fifty years almost!”“Not at all!” From Miss Pross.

“You think there never might have been a Mrs. Lorry?” asked the gentleman of that name.

“Pooh!” rejoined Miss Pross; “you were a bachelor in your cradle.”

“Well!” observed Mr. Lorry, beamingly adjusting his little wig, “that seems probable, too.”

...

In the hope of his recovery, and of resort to this third course being thereby rendered practicable, Mr. Lorry resolved to watch him attentively, with as little appearance as possible of doing so. He therefore made arrangements to absent himself from Tellson’s for the first time in his life, and took his post by the window in the same room.

Is Mr. Lorry my favorite character in all of Dickens? Possibly.

There may be a lot of sacrifice happening in this book, but is there any more challenging a sacrifice to pull off than Lorry altering his lifelong habits so far as to absent himself from Tellson's on his friend's behalf?

He and Pross make such a great pair, too. I would be rooting for them to get married if they weren't so much more delightful as independent friends.

Thank you for recalling that exchange between Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry, Julie. One of the few light moments in this very heavy story. It would be a stretch to say that Mr. Lorry is one of my favorite characters in all of Dickens, but I do like him. It's definitely a sacrifice for him to give up his life-long routines and responsibilities. I question the wisdom behind his decision to hide Dr. Manette's setback from Lucie, though.

Thank you for recalling that exchange between Miss Pross and Mr. Lorry, Julie. One of the few light moments in this very heavy story. It would be a stretch to say that Mr. Lorry is one of my favorite characters in all of Dickens, but I do like him. It's definitely a sacrifice for him to give up his life-long routines and responsibilities. I question the wisdom behind his decision to hide Dr. Manette's setback from Lucie, though.

Mary Lou wrote: "I question the wisdom behind his decision to hide Dr. Manette's setback from Lucie, though."

Mary Lou wrote: "I question the wisdom behind his decision to hide Dr. Manette's setback from Lucie, though."But telling her would mean treating Lucie like an adult, and we can't have that now, can we?

Mary Lou wrote: "the mender of roads

What an odd moniker. I was reminded, just phonetically, of the Colossus of Rhodes, which I really knew nothing about. Having looked it up, I don't really see anything symbolic ..."

In the light of a remark made by Peter in the preceding thread, I now think of the mender of roads as someone who prepares the roads with new flagstones so that the sound of the clogs can be heard. I don't think this was explicitly intended by Dickens because actually the mender of roads seems to play a minor role and he is certainly not a very inveterate revolutionary as yet, seeing how he cheers the King. But still, he seems to be a connection between the town and the countryside and maybe help spread the flame of upheaval to the peasants.

What an odd moniker. I was reminded, just phonetically, of the Colossus of Rhodes, which I really knew nothing about. Having looked it up, I don't really see anything symbolic ..."

In the light of a remark made by Peter in the preceding thread, I now think of the mender of roads as someone who prepares the roads with new flagstones so that the sound of the clogs can be heard. I don't think this was explicitly intended by Dickens because actually the mender of roads seems to play a minor role and he is certainly not a very inveterate revolutionary as yet, seeing how he cheers the King. But still, he seems to be a connection between the town and the countryside and maybe help spread the flame of upheaval to the peasants.

Mary Lou wrote: "Tristram wrote: "What do you think of the narrator’s light and comic treatment of domestic violence at the Crunchers’? Did Dickens really play this kind of thing for humour? ..."

Yeah, I think he ..."

I think that we have grown way too touchy and sensitive - so much so that I'm glad I am not a comedian because with my sense of humour I'd surely borrow trouble - but on the other hand, I could not find it in me to find the domestic plights of Mrs. Cruncher amusing. I felt similarly about Jeremiah Flintwinch and Affery, by the way.

Yeah, I think he ..."

I think that we have grown way too touchy and sensitive - so much so that I'm glad I am not a comedian because with my sense of humour I'd surely borrow trouble - but on the other hand, I could not find it in me to find the domestic plights of Mrs. Cruncher amusing. I felt similarly about Jeremiah Flintwinch and Affery, by the way.

Francis wrote: "This statement (copied above from Tristam) reminds me of Les Miserables and the revolutionary scenes of that novel.

"Another darkness was closing in as surely, when the church bells, then ringing ..."

She could at least represent a certain class, namely that of the petite bourgeoisie, the craftsmen, vendors, artisans, shopkeepers etc., who formed the bulk of the sans-culottes, i.e. those that Robespierre would base his power on.

"Another darkness was closing in as surely, when the church bells, then ringing ..."

She could at least represent a certain class, namely that of the petite bourgeoisie, the craftsmen, vendors, artisans, shopkeepers etc., who formed the bulk of the sans-culottes, i.e. those that Robespierre would base his power on.

Julie wrote: "Still, I don't think Elizabeth Gaskell would have done this."

She certainly wouldn't have done that kind of thing. I cannot think of any other Victorian writer but Dickens who would have done this, but wasn't it typical of some of Dickens's literary models, such as Fielding and Smollett?

She certainly wouldn't have done that kind of thing. I cannot think of any other Victorian writer but Dickens who would have done this, but wasn't it typical of some of Dickens's literary models, such as Fielding and Smollett?

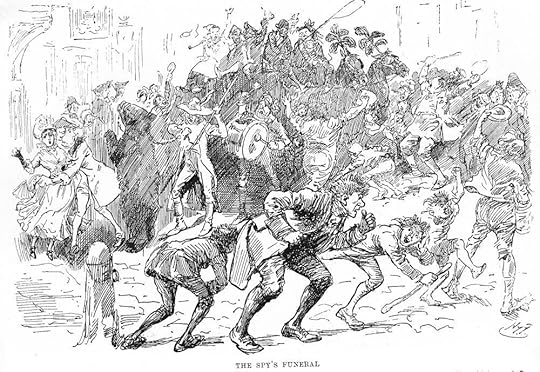

Book II Chapter 14 - Phiz - September 1859

The Spy's Funeral

Book II Chapter 14

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Funerals had at all times a remarkable attraction for Mr. Cruncher; he always pricked up his senses, and became excited, when a funeral passed Tellson's. Naturally, therefore, a funeral with this uncommon attendance excited him greatly, and he asked of the first man who ran against him:

"What is it, brother? What's it about?"

"I don't know," said the man. "Spies! Yaha! Tst! Spies!"

He asked another man. "Who is it?"

"I don't know," returned the man, clapping his hands to his mouth nevertheless, and vociferating in a surprising heat and with the greatest ardour, "Spies! Yaha! Tst, tst! Spi—ies!"

At length, a person better informed on the merits of the case, tumbled against him, and from this person he learned that the funeral was the funeral of one Roger Cly.

"Was He a spy?" asked Mr. Cruncher.

"Old Bailey spy," returned his informant. "Yaha! Tst! Yah! Old Bailey Spi—i—ies!"

"Why, to be sure!" exclaimed Jerry, recalling the Trial at which he had assisted. "I've seen him. Dead, is he?"

"Dead as mutton," returned the other, "and can't be too dead. Have 'em out, there! Spies! Pull 'em out, there! Spies!"

The idea was so acceptable in the prevalent absence of any idea, that the crowd caught it up with eagerness, and loudly repeating the suggestion to have 'em out, and to pull 'em out, mobbed the two vehicles so closely that they came to a stop. On the crowd's opening the coach doors, the one mourner scuffled out of himself and was in their hands for a moment; but he was so alert, and made such good use of his time, that in another moment he was scouring away up a bye-street, after shedding his cloak, hat, long hatband, white pocket-handkerchief, and other symbolical tears.

These, the people tore to pieces and scattered far and wide with great enjoyment, while the tradesmen hurriedly shut up their shops; for a crowd in those times stopped at nothing, and was a monster much dreaded. They had already got the length of opening the hearse to take the coffin out, when some brighter genius proposed instead, its being escorted to its destination amidst general rejoicing. Practical suggestions being much needed, this suggestion, too, was received with acclamation, and the coach was immediately filled with eight inside and a dozen out, while as many people got on the roof of the hearse as could by any exercise of ingenuity stick upon it. Among the first of these volunteers was Jerry Cruncher himself, who modestly concealed his spiky head from the observation of Tellson's, in the further corner of the mourning coach.

The officiating undertakers made some protest against these changes in the ceremonies; but, the river being alarmingly near, and several voices remarking on the efficacy of cold immersion in bringing refractory members of the profession to reason, the protest was faint and brief. The remodelled procession started, with a chimney-sweep driving the hearse—advised by the regular driver, who was perched beside him, under close inspection, for the purpose—and with a pieman, also attended by his cabinet minister, driving the mourning coach. A bear-leader, a popular street character of the time, was impressed as an additional ornament, before the cavalcade had gone far down the Strand; and his bear, who was black and very mangy, gave quite an Undertaking air to that part of the procession in which he walked.

The Spy's Funeral

Book II Chapter 14

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"Funerals had at all times a remarkable attraction for Mr. Cruncher; he always pricked up his senses, and became excited, when a funeral passed Tellson's. Naturally, therefore, a funeral with this uncommon attendance excited him greatly, and he asked of the first man who ran against him:

"What is it, brother? What's it about?"

"I don't know," said the man. "Spies! Yaha! Tst! Spies!"

He asked another man. "Who is it?"

"I don't know," returned the man, clapping his hands to his mouth nevertheless, and vociferating in a surprising heat and with the greatest ardour, "Spies! Yaha! Tst, tst! Spi—ies!"

At length, a person better informed on the merits of the case, tumbled against him, and from this person he learned that the funeral was the funeral of one Roger Cly.

"Was He a spy?" asked Mr. Cruncher.

"Old Bailey spy," returned his informant. "Yaha! Tst! Yah! Old Bailey Spi—i—ies!"

"Why, to be sure!" exclaimed Jerry, recalling the Trial at which he had assisted. "I've seen him. Dead, is he?"

"Dead as mutton," returned the other, "and can't be too dead. Have 'em out, there! Spies! Pull 'em out, there! Spies!"

The idea was so acceptable in the prevalent absence of any idea, that the crowd caught it up with eagerness, and loudly repeating the suggestion to have 'em out, and to pull 'em out, mobbed the two vehicles so closely that they came to a stop. On the crowd's opening the coach doors, the one mourner scuffled out of himself and was in their hands for a moment; but he was so alert, and made such good use of his time, that in another moment he was scouring away up a bye-street, after shedding his cloak, hat, long hatband, white pocket-handkerchief, and other symbolical tears.

These, the people tore to pieces and scattered far and wide with great enjoyment, while the tradesmen hurriedly shut up their shops; for a crowd in those times stopped at nothing, and was a monster much dreaded. They had already got the length of opening the hearse to take the coffin out, when some brighter genius proposed instead, its being escorted to its destination amidst general rejoicing. Practical suggestions being much needed, this suggestion, too, was received with acclamation, and the coach was immediately filled with eight inside and a dozen out, while as many people got on the roof of the hearse as could by any exercise of ingenuity stick upon it. Among the first of these volunteers was Jerry Cruncher himself, who modestly concealed his spiky head from the observation of Tellson's, in the further corner of the mourning coach.

The officiating undertakers made some protest against these changes in the ceremonies; but, the river being alarmingly near, and several voices remarking on the efficacy of cold immersion in bringing refractory members of the profession to reason, the protest was faint and brief. The remodelled procession started, with a chimney-sweep driving the hearse—advised by the regular driver, who was perched beside him, under close inspection, for the purpose—and with a pieman, also attended by his cabinet minister, driving the mourning coach. A bear-leader, a popular street character of the time, was impressed as an additional ornament, before the cavalcade had gone far down the Strand; and his bear, who was black and very mangy, gave quite an Undertaking air to that part of the procession in which he walked.

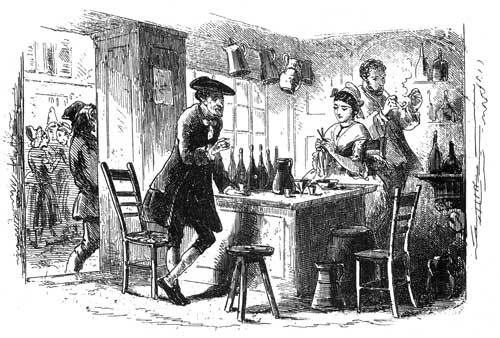

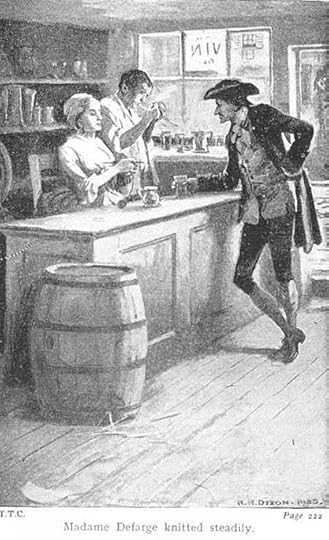

The Wine Shop

Book II Chapter 15

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

"It may have been a signal for loosening the general tongue. It elicited an answering chorus of "Good day!"

"It is bad weather, gentlemen," said Defarge, shaking his head.

Upon which, every man looked at his neighbour, and then all cast down their eyes and sat silent. Except one man, who got up and went out.

"My wife," said Defarge aloud, addressing Madame Defarge: "I have travelled certain leagues with this good mender of roads, called Jacques. I met him—by accident—a day and half's journey out of Paris. He is a good child, this mender of roads, called Jacques. Give him to drink, my wife!"

A second man got up and went out. Madame Defarge set wine before the mender of roads called Jacques, who doffed his blue cap to the company, and drank. In the breast of his blouse he carried some coarse dark bread; he ate of this between whiles, and sat munching and drinking near Madame Defarge's counter. A third man got up and went out.

Defarge refreshed himself with a draught of wine—but, he took less than was given to the stranger, as being himself a man to whom it was no rarity—and stood waiting until the countryman had made his breakfast. He looked at no one present, and no one now looked at him; not even Madame Defarge, who had taken up her knitting, and was at work.

"Have you finished your repast, friend?" he asked, in due season.

"Yes, thank you."

"Come, then! You shall see the apartment that I told you you could occupy. It will suit you to a marvel."

Commentary:

Again, horses, numerous figures (28 in the Paris street, 35 in the English street), and multiple focal points suggest parallel scene construction. Appropriate to the release of animal spirits in "The Spy's Funeral," there is only one woman, as opposed to at least five in "The Stoppage at the Fountain" in the previous month's installment. In contrast to the sounds of the horses, the consternation of the men, and the lachrymose lamentations of the women in "The Stoppage at the Fountain," in the essentially comedic "The Spy's Funeral" we hear sounds of communal festivity: three 'common' musical instruments (proletarian trumpet, drum, and fiddle), and the boisterous play of the leap-frogging street urchins — indeed, as opposed to the marble children of the French fountain, the English scene bubbles over with the youthful vivacity of living children, consistent with Dickens's piling present participles on top of each other to describe the scene: "with beer-drinking, pipe-smoking, song-roaring, and infinite caricaturing of woe, the disorderly procession went its way, recruiting at every step, and all the shops shutting up before it". In the Parisian scene, the fountain, the houses, and in particular the clogs clearly establish the scene's context rather more clearly than the signs (left) and the house-tops (right). In "The Spy's Funeral" adults' shoes contrast the children's bare feet to indicate the social strata represented and the playful nature of this more carefree crowd. Finally, the overall movement, right to left, is unimpeded in both scenes: the direction as suggested by the faces of all present is reinforced by the horses' heads, left of center in each plate.

Structurally as well as thematically, "The Stoppage at the Fountain" (August) and "The Spy's Funeral" (September) are visual complements, for in each case a crowd reacts to a death in a right-to-left movement of a carriage bearing an object of opprobrium — the indignant Marquis and the spy. Within these large group, historical genre pictures is a strong sense of violent, swirling, confusing motion complementing each plate's dominant mood; to convey all this, each crowd scene has several focal points. The English street again involves a communal response, general rejoicing over the death of a spy, whose casket we cannot see, and a shadowy figure just emerging from the doorway, extreme right.

The September pairing depends upon a series of binary oppositions: London/Paris, outdoors/indoors, crowd/limited cast, exuberant emotionalism/dispassionate conversation, kinetic/static. In "The Spy's Funeral," the bear-leader has just been pressed into the service of the rag-tag mob accompanying Barsad's corpse to the cemetery. In contrast, all appears serene in the little St. Antoine wine-shop run by the habitually smoking Defarge and his perpetually knitting wife.

"Mr. Stryver at Tellson's Bank," Book II, Chapter 2 (for August), and "The Wine-Shop," Book II, Chapter 6 (for September), help the reader draw parallels and make differentiations between the two cities and knit up the plot. Both scenes ostensibly concern business — the ledgers in the London counting house (symbolic of British commerce, and, by extension, British society) are paralleled by the bottles of the Defarges' St. Antoine wine-shop. In the background of the Tellson's scene, three men count bags of money, apparently for deposit, the iron grates here (suggestive of the need for security) contrasting the fifteen-paned window of the wine-shop. Outside the Defarges' door, women gossip in the street as a male idler attempts to overhear the conversation between the publicans and the spy. The close-up structure of both scenes does not permit us to see whether there are other patrons, but the rose in Madame Defarge's cap is a detail consistent with the printed text, and we may therefore assume that this signal has momentarily cleared the shop of customers. The precise moment captured seems to be that at which Barsad (seen in the plates for the first time) informs the Defarges that Lucie is to marry Charles Darnay (otherwise, D'Aulnais on his mother's side and St. Evrémonde on his father's), in effect, the present Marquis.

Whereas Browne's Defarge seems unperturbed, Dickens's betrays his emotion at this "intelligence": "Do what he would, behind the little counter, as to striking of a light and the lighting of his pipe, he was troubled, and his hand not trustworthy" (Book II, Chapter 6). although Dickens says that the effect of this news is "palpable," Browne has not chosen to reveal it. Rather, he has chosen to depict a tranquil surface whose undercurrents he signals to us through the male idler just beyond the lintel, for his Jacobin cap is a visual reminder of the revolutionary nature of the establishment roughly equivalent to Barsad's hailing Defarge as "Jacques," the code-name for a member of the clandestine Jacquerie. A clear symbol of the coming social cataclysm, the idler is seen through the doorway in roughly the same position in "The Wine- Shop" as the fashionably-dressed gentleman in the greatcoat and sporting a cane who is apparently depositing three bags of coins, details all suggestive of Britain's mercantile establishment, in "Mr. Stryver at Tellson's Bank."

The common activity (the graphic subtext, if you will) in these scenes is recording, for Madame Defarge's knitting is as much a ledger as the large tome on Mr. Lorry's desk, right of center. The chair and large pot of the wine-shop are paralleled by the stool and waste-basket in Tellson's, occupying a similar position in both plates. Despite the differences in their trade and clients, the St. Antoine wine-shop is the counterpart of the bank hard by Temple Bar, for information as well as coin is exchanged in both establishments, the former run by implacable foes of the aristocracy, the latter superintended by the protector of Lucie Darnay and frequented by French émigrés in search of news of home after the outbreak of the Revolution. The aristocratic and monied clientele of Tellson's are in marked contrast to the scarecrow paupers (covert radicals) who haunt the wine-shop, which becomes a grassroots insurrectionist stronghold after the storming of the Bastille (depicted on the Paris skyline of "The Sea Rises," Browne's plate for October). In addition to being centers of recording, the wine-shop and Tellson's are repositories of records. The weighty volumes on the shelf behind Mr. Lorry bespeak years of financial transactions (deposits and withdrawals), and assure the financial survival of those French aristocrats wise enough to deposit in a Parisian bank with a London house. In Madame Defarge's equally copious coded ledgers are accounts of the aristocracy's heinous domestic crimes and familial lineages. Behind these quiet genre scenes lie the essential differences in the societies of the two cities of the tale; the prosperity of a relatively free trading people implies that they will not experience the mob violence of "The Sea Rises" that proletarian poverty and exploitation across the water have virtually foredoomed, although, as "The Spy's Funeral" suggests, the potential for such violence lies within English society also.

Headnote Vignette

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 14 ("The Honest Tradesman")

Harper's Weekly (July 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"It was now Young Jerry's turn to approach the gate: which he did, holding his breath. Crouching down again in a corner there, and looking in, he made out the three fishermen creeping through some rank grass! and all the gravestones in the churchyard—it was a large churchyard that they were in—looking on like ghosts in white, while the church tower itself looked on like the ghost of a monstrous giant. They did not creep far, before they stopped and stood upright. And then they began to fish.

They fished with a spade, at first. Presently the honoured parent appeared to be adjusting some instrument like a great corkscrew. Whatever tools they worked with, they worked hard, until the awful striking of the church clock so terrified Young Jerry, that he made off, with his hair as stiff as his father's.

But, his long-cherished desire to know more about these matters, not only stopped him in his running away, but lured him back again. They were still fishing perseveringly, when he peeped in at the gate for the second time; but, now they seemed to have got a bite. There was a screwing and complaining sound down below, and their bent figures were strained, as if by a weight. By slow degrees the weight broke away the earth upon it, and came to the surface. Young Jerry very well knew what it would be; but, when he saw it, and saw his honoured parent about to wrench it open, he was so frightened, being new to the sight, that he made off again, and never stopped until he had run a mile or more.

He would not have stopped then, for anything less necessary than breath, it being a spectral sort of race that he ran, and one highly desirable to get to the end of. He had a strong idea that the coffin he had seen was running after him; and, pictured as hopping on behind him, bolt upright, upon its narrow end, always on the point of overtaking him and hopping on at his side—perhaps taking his arm—it was a pursuer to shun. It was an inconsistent and ubiquitous fiend too, for, while it was making the whole night behind him dreadful, he darted out into the roadway to avoid dark alleys, fearful of its coming hopping out of them like a dropsical boy's Kite without tail and wings. It hid in doorways too, rubbing its horrible shoulders against doors, and drawing them up to its ears, as if it were laughing. It got into shadows on the road, and lay cunningly on its back to trip him up. All this time it was incessantly hopping on behind and gaining on him, so that when the boy got to his own door he had reason for being half dead. And even then it would not leave him, but followed him upstairs with a bump on every stair, scrambled into bed with him, and bumped down, dead and heavy, on his breast when he fell asleep."

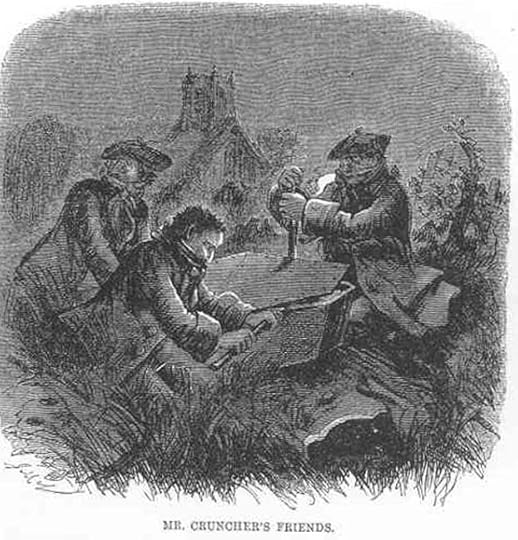

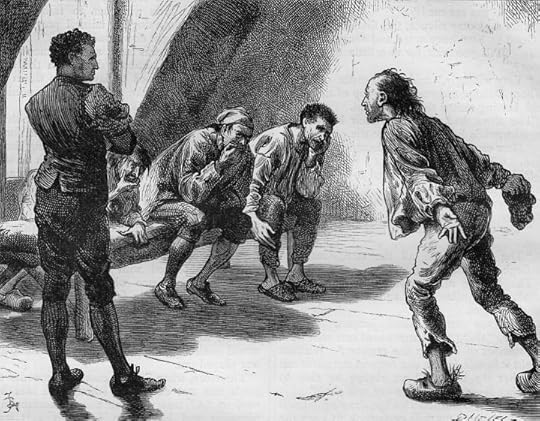

Mr. Cruncher's Friends

John McLenan

Book II Chapter 14

Dicken's A Tale of Two Cities

Harper's Weekly July 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Young Jerry, who had only made a feint of undressing when he went to bed, was not long after his father. Under cover of the darkness he followed out of the room, followed down the stairs, followed down the court, followed out into the streets. He was in no uneasiness concerning his getting into the house again, for it was full of lodgers, and the door stood ajar all night.

Impelled by a laudable ambition to study the art and mystery of his father's honest calling, Young Jerry, keeping as close to house fronts, walls, and doorways, as his eyes were close to one another, held his honoured parent in view. The honoured parent steering Northward, had not gone far, when he was joined by another disciple of Izaak Walton, and the two trudged on together.

Within half an hour from the first starting, they were beyond the winking lamps, and the more than winking watchmen, and were out upon a lonely road. Another fisherman was picked up here—and that so silently, that if Young Jerry had been superstitious, he might have supposed the second follower of the gentle craft to have, all of a sudden, split himself into two.

The three went on, and Young Jerry went on, until the three stopped under a bank overhanging the road. Upon the top of the bank was a low brick wall, surmounted by an iron railing. In the shadow of bank and wall the three turned out of the road, and up a blind lane, of which the wall—there, risen to some eight or ten feet high—formed one side. Crouching down in a corner, peeping up the lane, the next object that Young Jerry saw, was the form of his honoured parent, pretty well defined against a watery and clouded moon, nimbly scaling an iron gate. He was soon over, and then the second fisherman got over, and then the third. They all dropped softly on the ground within the gate, and lay there a little—listening perhaps. Then, they moved away on their hands and knees.

It was now Young Jerry's turn to approach the gate: which he did, holding his breath. Crouching down again in a corner there, and looking in, he made out the three fishermen creeping through some rank grass! and all the gravestones in the churchyard—it was a large churchyard that they were in—looking on like ghosts in white, while the church tower itself looked on like the ghost of a monstrous giant. They did not creep far, before they stopped and stood upright. And then they began to fish."

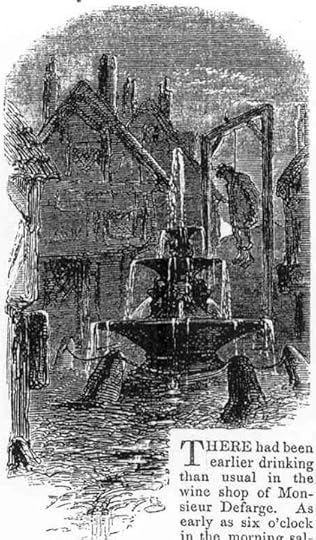

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 15 ("Knitting")

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At midday, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag — tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it, by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "On the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and the children draw water! Who can gossip of an evening, under that shadow! Under it, have I said? When I left the village, Monday evening as the sun was going to bed, and looked back from the hill, the shadow struck across the church, across the mill, across the prison — seemed to strike across the earth, messieurs, to where the sky rests upon it!"

"He described it as if he were there —"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Ch. XV, "Knitting"

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"I stand aside, messieurs, by my heap of stones, to see the soldiers and their prisoner pass (for it is a solitary road, that, where any spectacle is well worth looking at), and at first, as they approach, I see no more than that they are six soldiers with a tall man bound, and that they are almost black to my sight — except on the side of the sun going to bed, where they have a red edge, messieurs. Also, I see that their long shadows are on the hollow ridge on the opposite side of the road, and are on the hill above it, and are like the shadows of giants. Also, I see that they are covered with dust, and that the dust moves with them as they come, tramp, tramp! But when they advance quite near to me, I recognise the tall man, and he recognises me. Ah, but he would be well content to precipitate himself over the hill-side once again, as on the evening when he and I first encountered, close to the same spot!"

He described it as if he were there, and it was evident that he saw it vividly; perhaps he had not seen much in his life.

"I do not show the soldiers that I recognise the tall man; he does not show the soldiers that he recognises me; we do it, and we know it, with our eyes. `Come on!' says the chief of that company, pointing to the village, `bring him fast to his tomb!' and they bring him faster. I follow. His arms are swelled because of being bound so tight, his wooden shoes are large and clumsy, and he is lame. Because he is lame, and consequently slow, they drive him with their guns — like this!"

He imitated the action of a man's being impelled forward by the butt-ends of muskets.

"As they descend the hill like madmen running a race, he falls. They laugh and pick him up again. His face is bleeding and covered with dust, but he cannot touch it; thereupon they laugh again. They bring him into the village; all the village runs to look; they take him past the mill, and up to the prison; all the village sees the prison gate open in the darkness of the night, and swallow him — like this!"

He opened his mouth as wide as he could, and shut it with a sounding snap of his teeth. Observant of his unwillingness to mar the effect by opening it again, Defarge said, "Go on, Jacques."

Headnote Vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 16, "Still Knitting"

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"Madame Defarge and monsieur her husband returned amicably to the bosom of Saint Antoine, while a speck in a blue cap toiled through the darkness, and through the dust, and down the weary miles of avenue by the wayside, slowly tending towards that point of the compass where the chateau of Monsieur the Marquis, now in his grave, listened to the whispering trees. Such ample leisure had the stone faces, now, for listening to the trees and to the fountain, that the few village scarecrows who, in their quest for herbs to eat and fragments of dead stick to burn, strayed within sight of the great stone courtyard and terrace staircase, had it borne in upon their starved fancy that the expression of the faces was altered. A rumour just lived in the village — had a faint and bare existence there, as its people had — that when the knife struck home, the faces changed, from faces of pride to faces of anger and pain; also, that when that dangling figure was hauled up forty feet above the fountain, they changed again, and bore a cruel look of being avenged, which they would henceforth bear for ever. In the stone face over the great window of the bed-chamber where the murder was done, two fine dints were pointed out in the sculptured nose, which everybody recognised, and which nobody had seen of old; and on the scarce occasions when two or three ragged peasants emerged from the crowd to take a hurried peep at Monsieur the Marquis petrified, a skinny finger would not have pointed to it for a minute, before they all started away among the moss and leaves, like the more fortunate hares who could find a living there.

Chateau and hut, stone face and dangling figure, the red stain on the stone floor, and the pure water in the village well — thousands of acres of land — a whole province of France — all France itself — lay under the night sky, concentrated into a faint hair-breadth line. So does a whole world, with all its greatnesses and littlenesses, lie in a twinkling star. And as mere human knowledge can split a ray of light and analyse the manner of its composition, so, sublimer intelligences may read in the feeble shining of this earth of ours, every thought and act, every vice and virtue, of every responsible creature on it."

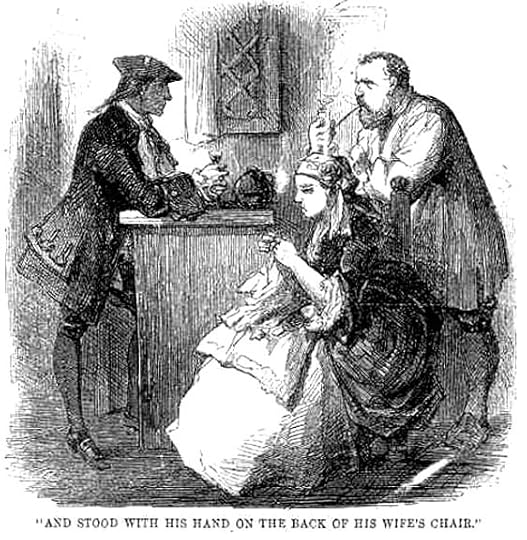

"And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair"

John McLenan

Illustration for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities,Book II, Chapter 16, "Still Knitting." [The spy, John Barsad, drinks a glass of cognac with Defarges]

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"It is all the same," said the spy, airily, but discomfited too: "good day!"

"Good day!" answered Defarge, drily.

"I was saying to madame, with whom I had the pleasure of chatting when you entered, that they tell me there is — and no wonder! — much sympathy and anger in Saint Antoine, touching the unhappy fate of poor Gaspard."

"No one has told me so," said Defarge, shaking his head. "I know nothing of it."

Having said it, he passed behind the little counter, and stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair, looking over that barrier at the person to whom they were both opposed, and whom either of them would have shot with the greatest satisfaction.

The spy, well used to his business, did not change his unconscious attitude, but drained his little glass of cognac, took a sip of fresh water, and asked for another glass of cognac. Madame Defarge poured it out for him, took to her knitting again, and hummed a little song over it.

"You seem to know this quarter well; that is to say, better than I do?" observed Defarge.

"Not at all, but I hope to know it better. I am so profoundly interested in its miserable inhabitants."

"Hah!" muttered Defarge.

Commentary:

Like Phiz, McLenan in his series for Harper's Weekly focused on the earlier scene in the wine shop, realizing the three figures rather than the shop's interior, in "And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair". McLenan's figure of Madame Defarge is far less appealing than either Phiz's or Barnard's, and McLenan's spy is surprisingly well dressed for a man whose profession's cardinal rule is, "Blend in.

Headnote Vignette,

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Ch. 17, "One Night"

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

I have no idea how this illustration goes with this chapter.

"'See!' said the Doctor of Beauvais"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book II, Chapter 17, "One Night"

Harper's Weekly (August 1859)

Text Illustrated:

"It was the first time, except at the trial, of her ever hearing him refer to the period of his suffering. It gave her a strange and new sensation while his words were in her ears; and she remembered it long afterwards.

"See!" said the Doctor of Beauvais, raising his hand towards the moon. "I have looked at her from my prison-window, when I could not bear her light. I have looked at her when it has been such torture to me to think of her shining upon what I had lost, that I have beaten my head against my prison-walls. I have looked at her, in a state so dun and lethargic, that I have thought of nothing but the number of horizontal lines I could draw across her at the full, and the number of perpendicular lines with which I could intersect them." He added in his inward and pondering manner, as he looked at the moon, "It was twenty either way, I remember, and the twentieth was difficult to squeeze in."

The strange thrill with which she heard him go back to that time, deepened as he dwelt upon it; but, there was nothing to shock her in the manner of his reference. He only seemed to contrast his present cheerfulness and felicity with the dire endurance that was over."

"It is frightful, messieur..."

Book II Chapter 15

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Workmen dig, workmen hammer, soldiers laugh and sing; in the morning, by the fountain, there is raised a gallows forty feet high, poisoning the water."

The mender of roads looked through rather that at the low ceiling, and pointed as if he saw the gallows somewhere in the sky.

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At mid-day, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag — tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "on the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and children draw water? Who can gossip of an evening under that shadow?"

Commentary:

The animated figure of the road-mender from the little village of the Marquis St. Evrémonde, his wooden shoes the signifier of his rural origins, narrates the fate of the murderer of the Marquis, a wretch whose decaying corpse is now polluting the village's fountain and casting a blight on the social life of the little community. His audience in the chamber above the St. Antoine wine shop are Defarge (left) and the three radical revolutionaries, Jacques One, Two, and Three.

Barnard follows the tranquil scene of Carton's protestation of love for Lucie in England with a scene in the French capital that advances the plot surrounding the Defarges' determination to eradicate the race of St. Evrémonde.

Whereas Phiz selected, perhaps at Dickens's instruction, only those scenes with emotional and pictorial appeal, Barnard has attempted to realise key moments in the plot as well as to present studies of some of the key characters. McLenan, in contrast, was interested in objects that hold some special significance in the plot. In this instance, he focused on the village fountain, leaving little to the imagination of the horrified reader in the headnote vignette for "Knitting." He subsequently shows the same scene as Barnard selected from the chapter, but McLenan's figures are far less effectively modelled in "He described it as if he were there —" in the August 6th instalment in Harper's Weekly.

"Saint Antoine"

Text Illustrated:

"In the evening, at which season of all others Saint Antoine turned himself inside out, and sat on door-steps and window-ledges, and came to the corners of vile streets and courts, for a breath of air, Madame Defarge with her work in her hand was accustomed to pass from place to place and from group to group: a Missionary—there were many like her—such as the world will do well never to breed again. All the women knitted. They knitted worthless things; but, the mechanical work was a mechanical substitute for eating and drinking; the hands moved for the jaws and the digestive apparatus: if the bony fingers had been still, the stomachs would have been more famine-pinched.

But, as the fingers went, the eyes went, and the thoughts. And as Madame Defarge moved on from group to group, all three went quicker and fiercer among every little knot of women that she had spoken with, and left behind.

Her husband smoked at his door, looking after her with admiration. "A great woman," said he, "a strong woman, a grand woman, a frightfully grand woman!"

Darkness closed around, and then came the ringing of church bells and the distant beating of the military drums in the Palace Courtyard, as the women sat knitting, knitting. Darkness encompassed them. Another darkness was closing in as surely, when the church bells, then ringing pleasantly in many an airy steeple over France, should be melted into thundering cannon; when the military drums should be beating to drown a wretched voice, that night all potent as the voice of Power and Plenty, Freedom and Life. So much was closing in about the women who sat knitting, knitting, that they their very selves were closing in around a structure yet unbuilt, where they were to sit knitting, knitting, counting dropping heads."

Commentary:

The economically-depressed center of the imminent political revolution, the urban slum of St. Antoine, is a contrast to areas of eighteenth-century London that are crucial to the action: the Old Bailey, Tellson's Bank near Temple Bar, and Doctor Manette's house in Soho. Although the illustration is situated late in chapter 17, it reflects events in "Still Knitting." Returning home at night, the Defarges learn from their contact within the ranks of the police that another spy has been commissioned for their district, an Englishman named "John Barsad." Presumably Barnard's view of the environs of the Defarges' wine shop is next afternoon, after an inquisitive new-comer matching the very description given them of Barsad enters the shop and orders a cognac.

Barnard is again reluctant to duplicate a scene by his friend and mentor Hablot Knight Browne, so that he only obliquely realizes the scene in which the spy, John Barsad, arrives on the Defarges' doorstep in "The Wine-Shop" in Book 2, Chapter 6 (in the monthly part for September, 1859). In Phiz's illustration, the teaming street life is suggested by the movements of the slum's denizens glimpsed through the open door (left). Whereas Phiz emphasizes the apparent non-chalance of the knitting wife and smoking husband as they confront the government spy, Barnard provides what a cinematographer would term "an establishing shot" of the female-dominated breeding ground of the revolution. The textual moment realized in the sixteenth chapter of the second book, "Still Knitting," occurs after the visit of the spy.

Whereas Phiz elected to show the interior of the wine shop and just three figures, Barnard shows Madame Defarge (center) as a community organizer and social networker. He has identified her for the viewer by repeating her profile, her turban, and her pendulous ear-rings. The extension of the text is the relative solidarity of the women (left) as opposed to the quarrelsome nature of the male-dominated register of the picture, right, in which men in the doorway and street gesticulate and a pair of skeletal cats square off with one another at Madame Defarge's feet.

Book II Chapter 15 - Sol Eytinge Jr.

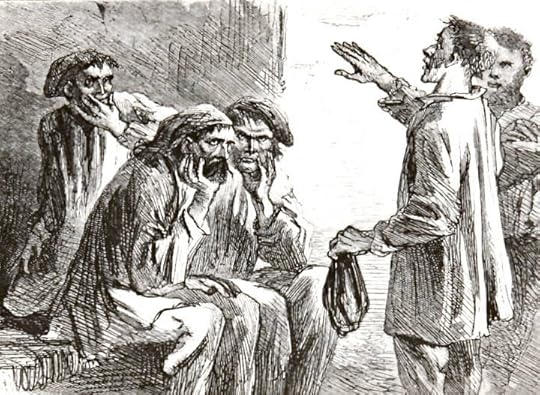

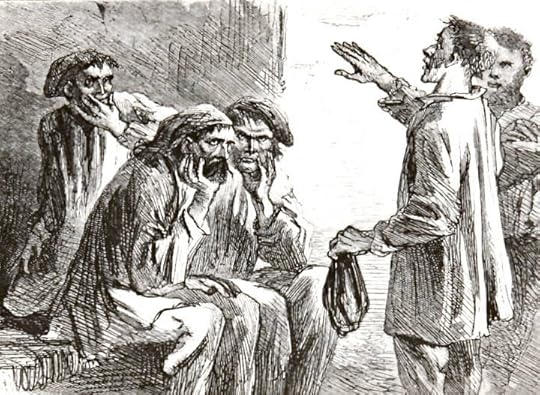

The Three Jacques

Book II Chapter 15

Sol Eytinge Jr,.

The Diamond Edition 1867

Commentary:

The 'Jacquerie' was the name given to the peasants' revolt in France in 1358, derived from the name 'Jacques Bonhomme', contemptuously applied to any peasant by the nobility. [Bentley et al., 131]

The group character study involves the revolutionary leader — Ernest Defarge, landlord of Saint Antoine's wine-shop — and his almost indistinguishable followers, the only individual among them being Jacques Three. Ten years later, and probably entirely without Eytinge's illustration for reference (given the effects of nineteenth-century copyright exclusivity for the American and British book markets), Fred Barnard selected almost precisely the same moment for realisation in his sequence of twenty-five illustrations for the Household Edition of the novel. In the garret to which Defarge leads them, he and his comrades receive with burning interest the road-mender's account of the execution of Gaspard:

"The looks of all of them were dark, repressed, and revengeful, as they listened to the countryman's story; the manner of all of them, while it was secret, was authoritative too. They had the air of a rough tribunal; Jacques One and Two sitting on the old pallet-bed, each with his chin resting on his hand, and his eyes intent on the road-mender; Jacques Three, equally intent, on one knee behind them, with his agitated hand always gliding over the network of fine nerves about his mouth and nose; Defarge standing between them and the narrator, whom he had stationed in the light of the window, by turns looking from him to them, and from them to him.

The raised gesture of the narrator, the road-mender, and the rapt attention of the Jacquerie, as well as the characteristic movement of The hand of Jacques Three to his mouth, suggest that the passage realised is likely this:

"Enough!" said Defarge, with grim impatience. "Long live the Devil! Go on."

"Well! Some whisper this, some whisper that; they speak of nothing else; even the fountain appears to fall to that tune. At length, on Sunday night when all the village is asleep, come soldiers, winding down from the prison, and their guns ring on the stones of the little street. Workmen dig, workmen hammer, soldiers laugh and sing; in the morning, by the fountain, there is raised a gallows forty feet high, poisoning the water."

The mender of roads looked through rather than at the low ceiling, and pointed as if he saw the gallows somewhere in the sky.

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At midday, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag-tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it, by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "On the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and the children draw water! Who can gossip of an evening, under that shadow! Under it, have I said? When I left the village, Monday evening as the sun was going to bed, and looked back from the hill, the shadow struck across the church, across the mill, across the prison — seemed to strike across the earth, messieurs, to where the sky rests upon it!" [Book 2, Chapter 15, "Knitting"]

Despite the care with which Phiz researched period costumes for his serial illustrations, he chose not to depict the book's clandestine revolutionaries, the Jacquerie, whereas both Eytinge in 1867 and Barnard in 1876 felt that these characters, generalized though they may be in Dickens's novel, were worthy of examination in order to place the redemptive action of the story in the context of the root causes and furtive planning of the revolution which led to the slaughter of thousands during the Reign of Terror. Paul Davis notes that members of the revolutionary brotherhood all adopted the secret name "Jacques," and that "Jacques Four" is the pseudonym which Ernest Defarge adopts in these meetings, which eventually involve the road-mender from the Marquis' village, an excitable peasant whom the brotherhood designate as "Jacques Five." By virtue of his position of narrator in Eytinge's sixth illustration, his gesture, and his cap with which he mops his perspiring brow, one may readily identify the road-mender as the man standing to the right.

However, aside from Defarge, in terms of the narrative the most important member of the Jacquerie assembled in the garret is Jacques Three, upon whom Davis passes no comment but about whom critic Harry Stone has much to say. Eytinge's depiction of the figure, alienated from his fellows at the back left, is consistent with Stone's interpretation in that this third, idiosyncratic "Jacques" is transfixed by the gruesome narrative unfolding. Jacques Three in the text is obsessed with the slaughter of the upper class, and in particular with the notion of large-scale blood-letting. Stone relates Dickens's creation of this character, whom the writer "tags" with a distinctive, repetitive gesture (touching the area immediately around his mouth), with the novelist's boyhood reading of The Terrific Register, a cheap periodical devoted to sensational and horrific disasters on land and sea, especially tales involving dismemberment and cannibalism. Eytinge sets Jacques Three apart from the others in this scene by virtue of his "restless hand and craving air" — realizing him as the "hungry man [who] gnawed one of his fingers as he looked at the other three" (Book Two, Chapter 15, "Knitting"), the other three being Defarge (behind the road-mender in Eytinge's realization) and the two in front of him on what is in fact the old pallet bed of Doctor Manette (as Barnard's illustration makes clear). As the road-mender describes the manner of Gaspard's protracted execution, Jacques Three cannot help but betray his own blood lust as "his finger quivered with the craving that was on him."

Eytinge's handling of the scene is comparatively realistic in manner and faithful to Dickens's text, right down to Jacques Five's cap and Jacque Three's touching his face, but lacks the telling details of the urban petite bourgeois' fashionable waistcoat, breeches, stockings, and buckled shoes — in sharp contrast to the rural road-mender's wooden shoes — and the clearly defined source of light in the upstairs garret that Barnard provides (left). However, as a close-up of the faces of the three Jacques Eytinge's illustration is still an effective complement to Dickens's rendering of the clandestine meeting, which concludes with a sentence of extinction for the entire Evrémonde family.

The Three Jacques

Book II Chapter 15

Sol Eytinge Jr,.

The Diamond Edition 1867

Commentary:

The 'Jacquerie' was the name given to the peasants' revolt in France in 1358, derived from the name 'Jacques Bonhomme', contemptuously applied to any peasant by the nobility. [Bentley et al., 131]

The group character study involves the revolutionary leader — Ernest Defarge, landlord of Saint Antoine's wine-shop — and his almost indistinguishable followers, the only individual among them being Jacques Three. Ten years later, and probably entirely without Eytinge's illustration for reference (given the effects of nineteenth-century copyright exclusivity for the American and British book markets), Fred Barnard selected almost precisely the same moment for realisation in his sequence of twenty-five illustrations for the Household Edition of the novel. In the garret to which Defarge leads them, he and his comrades receive with burning interest the road-mender's account of the execution of Gaspard:

"The looks of all of them were dark, repressed, and revengeful, as they listened to the countryman's story; the manner of all of them, while it was secret, was authoritative too. They had the air of a rough tribunal; Jacques One and Two sitting on the old pallet-bed, each with his chin resting on his hand, and his eyes intent on the road-mender; Jacques Three, equally intent, on one knee behind them, with his agitated hand always gliding over the network of fine nerves about his mouth and nose; Defarge standing between them and the narrator, whom he had stationed in the light of the window, by turns looking from him to them, and from them to him.

The raised gesture of the narrator, the road-mender, and the rapt attention of the Jacquerie, as well as the characteristic movement of The hand of Jacques Three to his mouth, suggest that the passage realised is likely this:

"Enough!" said Defarge, with grim impatience. "Long live the Devil! Go on."

"Well! Some whisper this, some whisper that; they speak of nothing else; even the fountain appears to fall to that tune. At length, on Sunday night when all the village is asleep, come soldiers, winding down from the prison, and their guns ring on the stones of the little street. Workmen dig, workmen hammer, soldiers laugh and sing; in the morning, by the fountain, there is raised a gallows forty feet high, poisoning the water."

The mender of roads looked through rather than at the low ceiling, and pointed as if he saw the gallows somewhere in the sky.

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At midday, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag-tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it, by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "On the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and the children draw water! Who can gossip of an evening, under that shadow! Under it, have I said? When I left the village, Monday evening as the sun was going to bed, and looked back from the hill, the shadow struck across the church, across the mill, across the prison — seemed to strike across the earth, messieurs, to where the sky rests upon it!" [Book 2, Chapter 15, "Knitting"]

Despite the care with which Phiz researched period costumes for his serial illustrations, he chose not to depict the book's clandestine revolutionaries, the Jacquerie, whereas both Eytinge in 1867 and Barnard in 1876 felt that these characters, generalized though they may be in Dickens's novel, were worthy of examination in order to place the redemptive action of the story in the context of the root causes and furtive planning of the revolution which led to the slaughter of thousands during the Reign of Terror. Paul Davis notes that members of the revolutionary brotherhood all adopted the secret name "Jacques," and that "Jacques Four" is the pseudonym which Ernest Defarge adopts in these meetings, which eventually involve the road-mender from the Marquis' village, an excitable peasant whom the brotherhood designate as "Jacques Five." By virtue of his position of narrator in Eytinge's sixth illustration, his gesture, and his cap with which he mops his perspiring brow, one may readily identify the road-mender as the man standing to the right.

However, aside from Defarge, in terms of the narrative the most important member of the Jacquerie assembled in the garret is Jacques Three, upon whom Davis passes no comment but about whom critic Harry Stone has much to say. Eytinge's depiction of the figure, alienated from his fellows at the back left, is consistent with Stone's interpretation in that this third, idiosyncratic "Jacques" is transfixed by the gruesome narrative unfolding. Jacques Three in the text is obsessed with the slaughter of the upper class, and in particular with the notion of large-scale blood-letting. Stone relates Dickens's creation of this character, whom the writer "tags" with a distinctive, repetitive gesture (touching the area immediately around his mouth), with the novelist's boyhood reading of The Terrific Register, a cheap periodical devoted to sensational and horrific disasters on land and sea, especially tales involving dismemberment and cannibalism. Eytinge sets Jacques Three apart from the others in this scene by virtue of his "restless hand and craving air" — realizing him as the "hungry man [who] gnawed one of his fingers as he looked at the other three" (Book Two, Chapter 15, "Knitting"), the other three being Defarge (behind the road-mender in Eytinge's realization) and the two in front of him on what is in fact the old pallet bed of Doctor Manette (as Barnard's illustration makes clear). As the road-mender describes the manner of Gaspard's protracted execution, Jacques Three cannot help but betray his own blood lust as "his finger quivered with the craving that was on him."

Eytinge's handling of the scene is comparatively realistic in manner and faithful to Dickens's text, right down to Jacques Five's cap and Jacque Three's touching his face, but lacks the telling details of the urban petite bourgeois' fashionable waistcoat, breeches, stockings, and buckled shoes — in sharp contrast to the rural road-mender's wooden shoes — and the clearly defined source of light in the upstairs garret that Barnard provides (left). However, as a close-up of the faces of the three Jacques Eytinge's illustration is still an effective complement to Dickens's rendering of the clandestine meeting, which concludes with a sentence of extinction for the entire Evrémonde family.

Monsieur and Madame Defarge

Book II Chapter 16

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Diamond Edition of Dicken's works 1867

Text Illustrated:

"This wine-shop keeper was a bull-necked, martial-looking man of thirty, and he should have been of a hot temperament, for, although it was a bitter day, he wore no coat, but carried one slung over his shoulder. His shirt-sleeves were rolled up, too, and his brown arms were bare to the elbows. Neither did he wear anything more on his head than his own crisply-curling short dark hair. He was a dark man altogether, with good eyes and a good bold breadth between them. Good-humoured looking on the whole, but implacable-looking, too; evidently a man of a strong resolution and a set purpose; a man not desirable to be met, rushing down a narrow pass with a gulf on either side, for nothing would turn the man.

Madame Defarge, his wife, sat in the shop behind the counter as he came in. Madame Defarge was a stout woman of about his own age, with a watchful eye that seldom seemed to look at anything, a large hand heavily ringed, a steady face, strong features, and great composure of manner. There was a character about Madame Defarge, from which one might have predicated that she did not often make mistakes against herself in any of the reckonings over which she presided. Madame Defarge being sensitive to cold, was wrapped in fur, and had a quantity of bright shawl twined about her head, though not to the concealment of her large earrings. Her knitting was before her, but she had laid it down to pick her teeth with a toothpick."

Commentary:

In contrast to the marriage of mismatched opposites Jerry and "Aggerawayter" Cruncher Eytinge presents the leaders of the clandestone revolutionary society, the Jacquerie, in Saint Antoine, the publicans or wine-shop keepers Ernest and Terese Defarge. Dickens introduces the couple early in the action, in "The Wine-shop".

All of these details of portraiture one may discern in this Eytinge illustration, which depicts Madame Defarge as still knitting as the spy, John Barsad, attempts to engage her and her husband in conversation. Eytinge's interpretation of the redoubtable middle-aged couple and of the impact upon them of the circumstances in which they find themselves in "Still Knitting" is more perceptive than Phiz's 1859 steel engraving "The Wine-shop", in which Defarge seems at ease and his demure, beautiful young wife wholly absorbed in her knitting. On the other hand, Eytinge has a couple who are appropriate extensions of Dickens's text, for they are both more mature and less physically attractive, and better individualized, even if the Diamond Edition's illustrator, who realizes little of their place of business, does not include Barsad in the picture, thereby in effect placing the viewer in Barsad's position. Under the penetrating gaze of the royalist regime's latest spy in the neighborhood Defarge fumbles to light his pipe. The spy artfully alludes to the inhumane execution of the Marquis' assassin, Gaspard, but the wily couple refuse to commit themselves to either an opinion on his fate or even to a sympathetic comment about the death of the poor man whose child perished under the wheels of Monseigneur's speeding carriage. Unperturbed, Madame Defarge coolly appraises the interlocutor, even as she checks her coded knitting's entry for John Barsad. Before the couple lies the cognac glass that the spy has just emptied, so that we can assume that Eytinge has illustrated precisely this dialogue:

"I was saying to madame, with whom I had the pleasure of chatting when you entered, that they tell me there is — and no wonder! — much sympathy and anger in Saint Antoine, touching the unhappy fate of poor Gaspard."

"No one has told me so," said Defarge, shaking his head. "I know nothing of it."

Having said it, he passed behind the little counter, and stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair, looking over that barrier at the person to whom they were both opposed, and whom either of them would have shot with the greatest satisfaction."

Book II Chapter 15 - Felix Octavius Carr Darley - This was used for the frontispiece

The Four Jacques

Felix Octavius Carr Darley

Book II Chapter 15

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Household Edition

Text Illustrated

"The mender of roads looked through rather than at the low ceiling, and pointed as if he saw the gallows somewhere in the sky.

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At midday, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag-tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it, by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "On the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and the children draw water! Who can gossip of an evening, under that shadow! Under it, have I said? When I left the village, Monday evening as the sun was going to bed, and looked back from the hill, the shadow struck across the church, across the mill, across the prison — seemed to strike across the earth, messieurs, to where the sky rests upon it!"

The hungry man gnawed one of his fingers as he looked at the other three, and his finger quivered with the craving that was on him."

Commentary:

Since the 1863 American Household Edition volumes neatly divide the novel at the end of Chapter 17 in Book Two, Darley's choice of subjects was likely intended to present the French Revolution in its "before" and "after" stages, with the clandestine plotters of the earlier part of the story becoming a mob bent on the annihilation of all aristocrats in the latter part. Although the nineteenth-century illustrators of the 1859 novel each have at least one scene in the Saint Antoine wine-shop of the Defarges, the original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne does not depict the malcontents above the shop; rather, he shows the recently-released Bastille prisoner there early in his series, in his second illustration for the first monthly installment, The Shoemaker, and then later in the series depicts the spy, John Barsad, interrogating the Defarges in one of the two September 1859 illustrations, The Wine-shop. Realizing, however, how important the plotters become once the Revolution has broken out, two of the book's 1860s American illustrators, John McLenan and Sol Eytinge, Jr., have included a realizations of this clandestine garret scene in their narrative-pictorial sequences. Whereas the weekly installments in All the Year Round have no illustrations whatsoever, the weekly installments in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization have at least two illustrations each, usually a regular wood-engraving (which becomes in the T. B. Peterson volume a full-page illustration) and a headnote vignette, a situation which gave McLenan the flexibility to alert the reader to an important event in the week's installment as well as to realize a significant moment in the action.

Thus, for Book Two, Chapter Fifteen (6 August 1859), McLenan actually shows the Marquis' assassin hanging above the fountain in the uncaptioned headnote vignette and then shows the narration of the avenger's fate in the garret above the shop, with Defarge nearest the window, the narrator (the road-mender) center, the look-a-like three Jacques listening intently (left). The inset narrator looks well advanced into middle age in these treatments of the scene, his hard life as a laborer belying his thirty-five years. At the conclusion of his inset narrative, the Jacquerie vote as "doomed to destruction" both the Evrémonde chateau and the entire family line, implying the "Extermination" of Darnay and his children. The scene visually accords well with its textual counterpart in terms of the setting and the juxtaposition of the figures in the dimly lit garret:

Defarge and the three glanced darkly at one another. The looks of all of them were dark, repressed, and revengeful, as they listened to the countryman's story; the manner of all of them, while it was secret, was authoritative too. They had the air of a rough tribunal; Jacques One and Two sitting on the old pallet-bed, each with his chin resting on his hand, and his eyes intent on the road-mender; Jacques Three, equally intent, on one knee behind them, with his agitated hand always gliding over the network of fine nerves about his mouth and nose; Defarge standing between them and the narrator, whom he had stationed in the light of the window, by turns looking from him to them, and from them to him. [Book 2, Chapter 15]

The most emotionally charged version of this critical scene occurs in Fred Barnard's illustrations for the 1874 Household Edition of the novel. Vividly realizing the scene as Dickens describes it, Fred Barnard frames the image of the road-mender's animatedly narrating events which occurred in the countryside with Dickens's own words, so that the reader encounters the image and text simultaneously — a decided advantage of the technology of wood-engraving in the 1870s. As opposed to Barnard's theatrical treatment, Darley's almost photographic treatment (with disposition of figures resembling that in McLenan's illustration) strikes the reader as subdued, but faithful to the text in terms of its detailing, Darley adding such elements as the floorboards, the low ceiling, and the crack in the wall, above center. Each of the three Jacques, sitting on the palette where Dr. Manette, recovering his wits after two decades of imprisonment, had slept, responds in a slightly different way to the narrative, consuming the story as thoughtfully as readers of the 1859 novel have done ever since its simultaneously serial publication on either side of the Atlantic. Darley distinguishes the thoughtful and observant publican, Defarge, from the others by his waistcoat and shirt, while the other Jacques and their guest have peasants' wooden shoes and caps. At the time, the reader casually notes such details, of course, encountering the small-scale photogravure plate proleptically, and then re-evaluating it with greater scrutiny when the narrative moment towards the end of volume one arrives. Only then will the reader appreciate the contrast between the bourgeois wine-shop proprietor (Jacques Four) to the rear of the listeners and the ragged trousers and smock frock of the bearded, uncouth peasant ("Jacques Five") who holds center-stage, as, blue cap in hand, he holds his listeners spellbound. Symbolically, having "the air of a rough tribunal", the group represents a fusion of radical interests, a disaffected urban proletariat, a restive peasantry, and a middle class bent on asserting its rights over the interests of an inept court and corrupt aristocracy.

The Four Jacques

Felix Octavius Carr Darley

Book II Chapter 15

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Household Edition

Text Illustrated

"The mender of roads looked through rather than at the low ceiling, and pointed as if he saw the gallows somewhere in the sky.

"All work is stopped, all assemble there, nobody leads the cows out, the cows are there with the rest. At midday, the roll of drums. Soldiers have marched into the prison in the night, and he is in the midst of many soldiers. He is bound as before, and in his mouth there is a gag-tied so, with a tight string, making him look almost as if he laughed." He suggested it, by creasing his face with his two thumbs, from the corners of his mouth to his ears. "On the top of the gallows is fixed the knife, blade upwards, with its point in the air. He is hanged there forty feet high — and is left hanging, poisoning the water."

They looked at one another, as he used his blue cap to wipe his face, on which the perspiration had started afresh while he recalled the spectacle.

"It is frightful, messieurs. How can the women and the children draw water! Who can gossip of an evening, under that shadow! Under it, have I said? When I left the village, Monday evening as the sun was going to bed, and looked back from the hill, the shadow struck across the church, across the mill, across the prison — seemed to strike across the earth, messieurs, to where the sky rests upon it!"

The hungry man gnawed one of his fingers as he looked at the other three, and his finger quivered with the craving that was on him."

Commentary: