The Old Curiosity Club discussion

A Tale of Two Cities

>

TTC Book 3 Chp 13-15

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Chapter 14

The Knitting Done

“It is a far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

We are fast approaching the end of this novel. How will Dickens resolve the outstanding issues and loose threads? Let’s begin with Madame Defarge. She holds a meeting at the shed of the wood-sawyer who was we first met him the road mender in earlier chapters. Madame Defarge thinks highly of her husband but realizes he has a soft spot for Doctor Manette. Madame Defarge says that she cares not if the Doctor lives or dies, but as for of Charles Darnay, “the wife and child must follow the husband and father.” Madame Defarge says she cannot trust her husband to see Lucie and little Lucie put to death. Thinking of her own family history, Madame Defarge has no qualms about exterminating the Evremonde family line.

Madame Defarge gives her knitting to the Vengeance and goes to find Lucie. Defarge carries a loaded pistol and a “sharpened dagger.” Meanwhile, we learn that Miss Pross and Jerry have not as yet left Paris. They have been charged with tending to the luggage of the group. Jerry promises that he will not pursue his evening profession to Miss Pross. For her part, Miss Pross only cares about Lucie and ignores Cruncher’s confession of guilt regarding his job as a resurrection man. As Cruncher and Pross talk, Madame Defarge comes closer and closer to them. Jerry goes off to make final preparations for their escape. Pross is alone; Madame Defarge appears. Miss Pross cries out, a basin of water falls to the floor, and the water flows to Madame Defarge’s feet. Symbolically, the blood-stained feet of Madame Defarge are now washed with water. What might this refer to or suggest?

To what extent could the water that flows to Madame Defarge’s feet be linked to the constant references to fountains that occur throughout the novel?

Madame Defarge demands to know where Lucie is. Miss Pross responds “You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer … . Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman.” Now, here are the great lines I have mentioned before. There is pride in the words, a defiance in the words, and, to my mind, a touch of needed humour in an otherwise rather bleak text. Defarge and Pross square off. There is no way Miss Pross will ever let Lucie down. Defarge and Miss Pross struggle. Pross, with the “vigorous tenacity of love, always much stronger than hate” holds onto Defarge. Miss Pross tells Defarge she will never let her reach her pistol and that “I’ll hold you till one or the other of us faints or dies!” The gun fires. Madame Defarge is shot. She dies.

Miss Pross leaves the room, locks the door and goes to meet Mr Cruncher at the cathedral. Worried that her actions may have been reported she asks Jerry if there is any noise in the street. Miss Pross recounts that there “had been a flash and a crash, and that crash was the last thing I should ever hear in this life.” As the chapter ends we are told that Miss Pross could not hear the rumble of the “dreadful carts.” Miss Pross is deaf and will never hear another sound in the world.

Thoughts

I have always wondered about Miss Pross’s hearing loss after her struggle with Madame Defarge. Why do you think Dickens made Miss Pross permanently deaf?

The Knitting Done

“It is a far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

We are fast approaching the end of this novel. How will Dickens resolve the outstanding issues and loose threads? Let’s begin with Madame Defarge. She holds a meeting at the shed of the wood-sawyer who was we first met him the road mender in earlier chapters. Madame Defarge thinks highly of her husband but realizes he has a soft spot for Doctor Manette. Madame Defarge says that she cares not if the Doctor lives or dies, but as for of Charles Darnay, “the wife and child must follow the husband and father.” Madame Defarge says she cannot trust her husband to see Lucie and little Lucie put to death. Thinking of her own family history, Madame Defarge has no qualms about exterminating the Evremonde family line.

Madame Defarge gives her knitting to the Vengeance and goes to find Lucie. Defarge carries a loaded pistol and a “sharpened dagger.” Meanwhile, we learn that Miss Pross and Jerry have not as yet left Paris. They have been charged with tending to the luggage of the group. Jerry promises that he will not pursue his evening profession to Miss Pross. For her part, Miss Pross only cares about Lucie and ignores Cruncher’s confession of guilt regarding his job as a resurrection man. As Cruncher and Pross talk, Madame Defarge comes closer and closer to them. Jerry goes off to make final preparations for their escape. Pross is alone; Madame Defarge appears. Miss Pross cries out, a basin of water falls to the floor, and the water flows to Madame Defarge’s feet. Symbolically, the blood-stained feet of Madame Defarge are now washed with water. What might this refer to or suggest?

To what extent could the water that flows to Madame Defarge’s feet be linked to the constant references to fountains that occur throughout the novel?

Madame Defarge demands to know where Lucie is. Miss Pross responds “You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer … . Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman.” Now, here are the great lines I have mentioned before. There is pride in the words, a defiance in the words, and, to my mind, a touch of needed humour in an otherwise rather bleak text. Defarge and Pross square off. There is no way Miss Pross will ever let Lucie down. Defarge and Miss Pross struggle. Pross, with the “vigorous tenacity of love, always much stronger than hate” holds onto Defarge. Miss Pross tells Defarge she will never let her reach her pistol and that “I’ll hold you till one or the other of us faints or dies!” The gun fires. Madame Defarge is shot. She dies.

Miss Pross leaves the room, locks the door and goes to meet Mr Cruncher at the cathedral. Worried that her actions may have been reported she asks Jerry if there is any noise in the street. Miss Pross recounts that there “had been a flash and a crash, and that crash was the last thing I should ever hear in this life.” As the chapter ends we are told that Miss Pross could not hear the rumble of the “dreadful carts.” Miss Pross is deaf and will never hear another sound in the world.

Thoughts

I have always wondered about Miss Pross’s hearing loss after her struggle with Madame Defarge. Why do you think Dickens made Miss Pross permanently deaf?

Chapter 15

The Footsteps Die Out Forever

“Twenty-Three”

The title of the chapter tells us that we have arrived at the last chapter. The footsteps first heard so long ago at the Manette’s home in a quiet corner of London are now gone. For Doctor Manette, the Darnay family, Mr Lorry, Jerry, and Miss Pross life will carry on. England has never yet suffered the spectre of a Revolution like the one in France. I’m sure that it was Dickens's hope that such a possibility would always remain fiction.

The beginning words of this chapter are “Along the Paris streets, the death-carts rumble, hollow and harsh.” It is the day of Charles Darnay’s execution and it is a public spectacle. When the crowds see him in the tumbril with his head is bowed he is talking to “a mere girl.” The reader knows it is not Charles Darnay who is going to his death. It is Sydney Carton, but Carton has no interest in the crowd or the crowd’s interest in him. We learn that one witness to this day is John Barsad. Barsad and Carton make eye contact. Barsad has kept his word not to expose Carton’s plan. I wonder what went through Barsad’s mind as he and Carton looked at each other? What do you think occurred at that moment?

The Vengeance realizes Madame Defarge is not present in her usual seat to watch the guillotine at work. She “cries, in her shrill tones” but Madame Defarge will never hear her. The Vengeance cries out again and says “See her knitting in my hand, and her empty chair ready for her. I cry with vexation and disappointment.” Cry all you want, Vengeance. Madame Defarge will never hear your voice again.

Sydney Carton and the young girl are lifted down from the tumbril. The girl says she thanks God that Sydney was there to offer hope and comfort.” Sydney replies “or you to me.” These two individuals, the young girl first, go to the guillotine. They both died believing that in a better place they will live forever and be reunited with those who are important to them. Both see a future that will embrace them for who they really are. The young girl goes first, Twenty-Two. Then Sydney, Twenty Three. Dickens quotes the words of John 11:25 “I am the Resurrection and the Life … “ as a benediction to the poor young girl and Carton, two people that the world, in its hurry, never truly saw or appreciated. Throughout the novel we have read the trope of being recalled to life. Here, I think, we clearly see the direction Dickens was heading throughout the novel made clear to the reader.

Thoughts

There is much to unpack in the novel, and we will have one final week for our final thoughts and reflections. For now, however, I wonder to what extent you have found this final chapter overly melodramatic?

In many final chapters of Dickens tells the reader what becomes of many of the characters in the novel. A Tale of Two Cities is no different. Let’s take a look into the future. Did you notice that the voice of the last few remaining paragraphs shifts? “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous, and happy, in that England which I will see no more.” Yes, Dickens has stepped aside from his primary role of narrator in order to allow Sydney Carton to speak directly to us. To me, this is remarkable. Sydney is given the power to see and comment on own his future. Sydney sees Lucie with a child upon her bosom that bears his name. He sees Doctor Manette an old man who still is a man of healing and peace. He sees Me Lorry remaining a faithful friend to the family until he passes from the world to his reward. He sees that his memory is held sacred in everyone’s hearts for generations to come. He sees Lucie and Charles, both dead, and knows both held him sacred in their souls. Sydney sees Lucie’s son, who is named Sydney, become the best and most illustrious of judges, and then this man brings his son to the grave to hear the story of Sydney Carton, who is not remembered as disfigured in any way, not socially, not morally or even physically, but a man remembered for who he truly was, and truly became.

I think A Tale of Two Cities begins with one of the greatest lines in literature. I also think the novel’s final lines are equally memorable. I imagine most of us are familiar with it: “It is a far, far better thing I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever known.” Is there any single book in literature with both a beginning and end that can match the power of A Tale of Two Cities”?

Numbers. On the day of Sydney’s death there are 52 people who are sent to the guillotine. What might be Dickens’s reason for selecting that number?

Sydney is the 23rd person to be put to death. Can you think of a reason for that number being selected by Dickens?

Next week, let’s open up our discussion for final thoughts and observations.

The Footsteps Die Out Forever

“Twenty-Three”

The title of the chapter tells us that we have arrived at the last chapter. The footsteps first heard so long ago at the Manette’s home in a quiet corner of London are now gone. For Doctor Manette, the Darnay family, Mr Lorry, Jerry, and Miss Pross life will carry on. England has never yet suffered the spectre of a Revolution like the one in France. I’m sure that it was Dickens's hope that such a possibility would always remain fiction.

The beginning words of this chapter are “Along the Paris streets, the death-carts rumble, hollow and harsh.” It is the day of Charles Darnay’s execution and it is a public spectacle. When the crowds see him in the tumbril with his head is bowed he is talking to “a mere girl.” The reader knows it is not Charles Darnay who is going to his death. It is Sydney Carton, but Carton has no interest in the crowd or the crowd’s interest in him. We learn that one witness to this day is John Barsad. Barsad and Carton make eye contact. Barsad has kept his word not to expose Carton’s plan. I wonder what went through Barsad’s mind as he and Carton looked at each other? What do you think occurred at that moment?

The Vengeance realizes Madame Defarge is not present in her usual seat to watch the guillotine at work. She “cries, in her shrill tones” but Madame Defarge will never hear her. The Vengeance cries out again and says “See her knitting in my hand, and her empty chair ready for her. I cry with vexation and disappointment.” Cry all you want, Vengeance. Madame Defarge will never hear your voice again.

Sydney Carton and the young girl are lifted down from the tumbril. The girl says she thanks God that Sydney was there to offer hope and comfort.” Sydney replies “or you to me.” These two individuals, the young girl first, go to the guillotine. They both died believing that in a better place they will live forever and be reunited with those who are important to them. Both see a future that will embrace them for who they really are. The young girl goes first, Twenty-Two. Then Sydney, Twenty Three. Dickens quotes the words of John 11:25 “I am the Resurrection and the Life … “ as a benediction to the poor young girl and Carton, two people that the world, in its hurry, never truly saw or appreciated. Throughout the novel we have read the trope of being recalled to life. Here, I think, we clearly see the direction Dickens was heading throughout the novel made clear to the reader.

Thoughts

There is much to unpack in the novel, and we will have one final week for our final thoughts and reflections. For now, however, I wonder to what extent you have found this final chapter overly melodramatic?

In many final chapters of Dickens tells the reader what becomes of many of the characters in the novel. A Tale of Two Cities is no different. Let’s take a look into the future. Did you notice that the voice of the last few remaining paragraphs shifts? “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous, and happy, in that England which I will see no more.” Yes, Dickens has stepped aside from his primary role of narrator in order to allow Sydney Carton to speak directly to us. To me, this is remarkable. Sydney is given the power to see and comment on own his future. Sydney sees Lucie with a child upon her bosom that bears his name. He sees Doctor Manette an old man who still is a man of healing and peace. He sees Me Lorry remaining a faithful friend to the family until he passes from the world to his reward. He sees that his memory is held sacred in everyone’s hearts for generations to come. He sees Lucie and Charles, both dead, and knows both held him sacred in their souls. Sydney sees Lucie’s son, who is named Sydney, become the best and most illustrious of judges, and then this man brings his son to the grave to hear the story of Sydney Carton, who is not remembered as disfigured in any way, not socially, not morally or even physically, but a man remembered for who he truly was, and truly became.

I think A Tale of Two Cities begins with one of the greatest lines in literature. I also think the novel’s final lines are equally memorable. I imagine most of us are familiar with it: “It is a far, far better thing I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest I go to than I have ever known.” Is there any single book in literature with both a beginning and end that can match the power of A Tale of Two Cities”?

Numbers. On the day of Sydney’s death there are 52 people who are sent to the guillotine. What might be Dickens’s reason for selecting that number?

Sydney is the 23rd person to be put to death. Can you think of a reason for that number being selected by Dickens?

Next week, let’s open up our discussion for final thoughts and observations.

I did not go back to count but it seems to me that Dickens used many quotes from the Bible in these last few chapters. I cannot remember any other Dickens book that quotes the Bible so often. Is Dickens getting religion? And I may be wrong on this - this is just the feeling that I had, every other page with a quote from the Bible. Did Dickens want me to know that he knows the Bible? peace, janz

I did not go back to count but it seems to me that Dickens used many quotes from the Bible in these last few chapters. I cannot remember any other Dickens book that quotes the Bible so often. Is Dickens getting religion? And I may be wrong on this - this is just the feeling that I had, every other page with a quote from the Bible. Did Dickens want me to know that he knows the Bible? peace, janz

Peter wrote: "Is there any single book in literature with both a beginning and end that can match the power of A Tale of Two Cities?"

Peter wrote: "Is there any single book in literature with both a beginning and end that can match the power of A Tale of Two Cities?"No. No there is not. :)

Peter wrote: "Did you notice that the voice of the last few remaining paragraphs shifts? “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous, and happy, in that England which I will see no more.” Yes, Dickens has stepped aside from his primary role of narrator in order to allow Sydney Carton to speak directly to us."

Peter wrote: "Did you notice that the voice of the last few remaining paragraphs shifts? “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous, and happy, in that England which I will see no more.” Yes, Dickens has stepped aside from his primary role of narrator in order to allow Sydney Carton to speak directly to us."This happens at the end of Chapter 13, two chapters previously, as well, in the last couple of pages where the narration shifts into first person plural. There's so much going on in these final chapters.

Peter wrote: "Chapter 14

Peter wrote: "Chapter 14The Knitting Done

“It is a far better thing that I do, than I have ever done; it is a far, far better rest that I go to than I have ever known.”

We are fast approaching the end of th..."

I loved all of this week's chapters, but this one struck me as especially perfect: the tension set into motion as Madame Defarge decides to set out for murder, the pause in the middle where the very funny discussion between Cruncher and Pross interlaced with reminders that Madame D is coming nearer and nearer as they speak, that stunning final confrontation (more mirrors!), and Miss Pross's terrified retreat.

In answer to Peter's question, I think Pross goes deaf because she's stepped so far beyond her acceptable role (even though it is courageous and right of her to do so) that she can't return to normal. Her experience has to leave her marked.

Mary Lou, while I was reading I wondered was this the chapter that had you screaming when you read it before?

Peacejanz wrote: "I did not go back to count but it seems to me that Dickens used many quotes from the Bible in these last few chapters. I cannot remember any other Dickens book that quotes the Bible so often. Is Di..."

Hi Peacejanz

Oh my, the question of Dickens and his position on religion has been debated for a long time. Were you aware that he wrote a book titled “The Life of Our Lord?” It was written expressly for his children and was never intended for public sale. In it, Dickens writes from a child’s reading perspective only about the New Testament. There were very few copies that existed. In the 1930’s the descendants of Dickens decided to publish it for public consumption. I often wonder if Jeopardy will ever ask the question “What is the last book of Dickens to be published?”

I think it was Dickens general intention to suggest that kindness, consideration, and forgiveness are ways we should follow in our lives and also important to share with our fellow humans. In terms of his own belief was Unitarian.

Hi Peacejanz

Oh my, the question of Dickens and his position on religion has been debated for a long time. Were you aware that he wrote a book titled “The Life of Our Lord?” It was written expressly for his children and was never intended for public sale. In it, Dickens writes from a child’s reading perspective only about the New Testament. There were very few copies that existed. In the 1930’s the descendants of Dickens decided to publish it for public consumption. I often wonder if Jeopardy will ever ask the question “What is the last book of Dickens to be published?”

I think it was Dickens general intention to suggest that kindness, consideration, and forgiveness are ways we should follow in our lives and also important to share with our fellow humans. In terms of his own belief was Unitarian.

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "Did you notice that the voice of the last few remaining paragraphs shifts? “I see the lives for which I lay down my life, peaceful, useful, prosperous, and happy, in that England whic..."

Hi Julie

Yes. When I step back from this novel I am constantly amazed how much is going on, the depths to which Dickens leads our minds, and the subtle beauty of his prose and his vision.

I agree with your comments about Pross’s deafness. She has killed someone. She does leave the scene. Now, while the death of Madame Defarge was justified, a death is still a death. This is a later novel of Dickens. As a mature novelist, Dickens cannot simply excuse her actions.

I loved your simple answer to my question about TTC’s opening sentence and final sentence.

Hi Julie

Yes. When I step back from this novel I am constantly amazed how much is going on, the depths to which Dickens leads our minds, and the subtle beauty of his prose and his vision.

I agree with your comments about Pross’s deafness. She has killed someone. She does leave the scene. Now, while the death of Madame Defarge was justified, a death is still a death. This is a later novel of Dickens. As a mature novelist, Dickens cannot simply excuse her actions.

I loved your simple answer to my question about TTC’s opening sentence and final sentence.

Thank you, Peter. I did not know that he was Unitarian, but it makes a lot of sense. Thanks for the info. I am going to try to get the last book. peace, janz

Thank you, Peter. I did not know that he was Unitarian, but it makes a lot of sense. Thanks for the info. I am going to try to get the last book. peace, janz

Making my way through the many illustrations there are for ATTC, I've discovered that Phiz did not draw any illustration for this last installment. Why he would skip these last chapters I haven't figured out yet, but whatever the reason may be, there are no Phiz illustrations for these chapters. The only thing I have left from Phiz is the title page, and the cover, and I will save those until after the other illustrators and their illustrations for these chapters. So I am moving on to John McLenan.

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 13 ("Fifty-two")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Charles Darnay, alone in a cell, had sustained himself with no flattering delusion since he came to it from the Tribunal. In every line of the narrative he had heard, he had heard his condemnation. He had fully comprehended that no personal influence could possibly save him, that he was virtually sentenced by the millions, and that units could avail him nothing."

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 13 ("Fifty-two")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Charles Darnay, alone in a cell, had sustained himself with no flattering delusion since he came to it from the Tribunal. In every line of the narrative he had heard, he had heard his condemnation. He had fully comprehended that no personal influence could possibly save him, that he was virtually sentenced by the millions, and that units could avail him nothing."

"Write exactly as I speak"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 13 ("Fifty-two")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Do I ask you, my dear Darnay, to pass the door? When I ask that, refuse. There are pen and ink and paper on this table. Is your hand steady enough to write?"

"It was when you came in."

"Steady it again, and write what I shall dictate. Quick, friend, quick!"

Pressing his hand to his bewildered head, Darnay sat down at the table. Carton, with his right hand in his breast, stood close beside him.

"Write exactly as I speak."

"To whom do I address it?"

"To no one." Carton still had his hand in his breast.

"Do I date it?"

"No."

The prisoner looked up, at each question. Carton, standing over him with his hand in his breast, looked down.

"`If you remember,'" said Carton, dictating, "`the words that passed between us, long ago, you will readily comprehend this when you see it. You do remember them, I know. It is not in your nature to forget them.'"

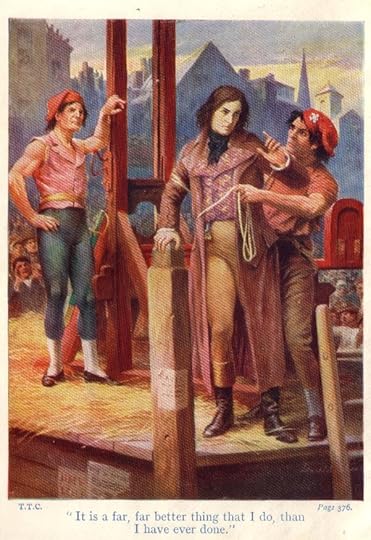

"Write exactly as I speak"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 13 ("Fifty-two")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Do I ask you, my dear Darnay, to pass the door? When I ask that, refuse. There are pen and ink and paper on this table. Is your hand steady enough to write?"

"It was when you came in."

"Steady it again, and write what I shall dictate. Quick, friend, quick!"

Pressing his hand to his bewildered head, Darnay sat down at the table. Carton, with his right hand in his breast, stood close beside him.

"Write exactly as I speak."

"To whom do I address it?"

"To no one." Carton still had his hand in his breast.

"Do I date it?"

"No."

The prisoner looked up, at each question. Carton, standing over him with his hand in his breast, looked down.

"`If you remember,'" said Carton, dictating, "`the words that passed between us, long ago, you will readily comprehend this when you see it. You do remember them, I know. It is not in your nature to forget them.'"

"Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, 14 ("The Knitting Done")

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"Lying hidden in her bosom, was a loaded pistol. Lying hidden at her waist, was a sharpened dagger. Thus accoutred, and walking with the confident tread of such a character, and with the supple freedom of a woman who had habitually walked in her girlhood, bare-foot and bare-legged, on the brown sea-sand, Madame Defarge took her way along the streets. . . .

"We are alone at the top of a high house in a solitary courtyard, we are not likely to be heard, and I pray for bodily strength to keep you here, while every minute you are here is worth a hundred thousand guineas to my darling," said Miss Pross.

Madame Defarge made at the door. Miss Pross, on the instinct of the moment, seized her round the waist in both her arms, and held her tight. It was in vain for Madame Defarge to struggle and to strike; Miss Pross, with the vigorous tenacity of love, always so much stronger than hate, clasped her tight, and even lifted her from the floor in the struggle that they had. The two hands of Madame Defarge buffeted and tore her face; but, Miss Pross, with her head down, held her round the waist, and clung to her with more than the hold of a drowning woman.

Soon, Madame Defarge's hands ceased to strike, and felt at her encircled waist. "It is under my arm," said Miss Pross, in smothered tones, "you shall not draw it. I am stronger than you, I bless Heaven for it. I hold you till one or other of us faints or dies!"

Madame Defarge's hands were at her bosom. Miss Pross looked up, saw what it was, struck at it, struck out a flash and a crash, and stood alone--blinded with smoke.

All this was in a second. As the smoke cleared, leaving an awful stillness, it passed out on the air, like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground.

In the first fright and horror of her situation, Miss Pross passed the body as far from it as she could, and ran down the stairs to call for fruitless help. Happily, she bethought herself of the consequences of what she did, in time to check herself and go back. It was dreadful to go in at the door again; but, she did go in, and even went near it, to get the bonnet and other things that she must wear. These she put on, out on the staircase, first shutting and locking the door and taking away the key. She then sat down on the stairs a few moments to breathe and to cry, and then got up and hurried away."

Headnote vignette

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, chapter 15

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"The clocks are on the stroke of three, and the furrow ploughed among the populace is turning round, to come on into the place of execution, and end. The ridges thrown to this side and to that, now crumble in and close behind the last plough as it passes on, for all are following to the Guillotine. In front of it, seated in chairs, as in a garden of public diversion, are a number of women, busily knitting. On one of the fore-most chairs, stands The Vengeance, looking about for her friend."

"Therese!" she cries, in her shrill tones. "Who has seen her? Therese Defarge!"

"She never missed before," says a knitting-woman of the sisterhood.

"No; nor will she miss now," cries The Vengeance, petulantly. "Therese."

"Louder," the woman recommends.

Ay! Louder, Vengeance, much louder, and still she will scarcely hear thee. Louder yet, Vengeance, with a little oath or so added, and yet it will hardly bring her. Send other women up and down to seek her, lingering somewhere; and yet, although the messengers have done dread deeds, it is questionable whether of their own wills they will go far enough to find her!

"Bad Fortune!" cries The Vengeance, stamping her foot in the chair, "and here are the tumbrils! And Evremonde will be despatched in a wink, and she not here! See her knitting in my hand, and her empty chair ready for her. I cry with vexation and disappointment!"

As The Vengeance descends from her elevation to do it, the tumbrils begin to discharge their loads. The ministers of Sainte Guillotine are robed and ready. Crash!—A head is held up, and the knitting-women who scarcely lifted their eyes to look at it a moment ago when it could think and speak, count One.

The second tumbril empties and moves on; the third comes up. Crash!—And the knitting-women, never faltering or pausing in their Work, count Two."

"The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims"

John McLenan

Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, Book III, 15, "The Footsteps Die Out Forever"

Harper's Weekly November 1859

Text Illustrated:

"The supposed Evremonde descends, and the seamstress is lifted out next after him. He has not relinquished her patient hand in getting out, but still holds it as he promised. He gently places her with her back to the crashing engine that constantly whirrs up and falls, and she looks into his face and thanks him.

"But for you, dear stranger, I should not be so composed, for I am naturally a poor little thing, faint of heart; nor should I have been able to raise my thoughts to Him who was put to death, that we might have hope and comfort here to-day. I think you were sent to me by Heaven."

"Or you to me," says Sydney Carton. "Keep your eyes upon me, dear child, and mind no other object."

"I mind nothing while I hold your hand. I shall mind nothing when I let it go, if they are rapid."

"They will be rapid. Fear not!"

The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims, but they speak as if they were alone. Eye to eye, voice to voice, hand to hand, heart to heart, these two children of the Universal Mother, else so wide apart and differing, have come together on the dark highway, to repair home together, and to rest in her bosom.

"Brave and generous friend, will you let me ask you one last question? I am very ignorant, and it troubles me—just a little."

"Tell me what it is."

"I have a cousin, an only relative and an orphan, like myself, whom I love very dearly. She is five years younger than I, and she lives in a farmer's house in the south country. Poverty parted us, and she knows nothing of my fate—for I cannot write—and if I could, how should I tell her! It is better as it is."

"Yes, yes: better as it is."

"What I have been thinking as we came along, and what I am still thinking now, as I look into your kind strong face which gives me so much support, is this:—If the Republic really does good to the poor, and they come to be less hungry, and in all ways to suffer less, she may live a long time: she may even live to be old."

"What then, my gentle sister?"

"Do you think:" the uncomplaining eyes in which there is so much endurance, fill with tears, and the lips part a little more and tremble: "that it will seem long to me, while I wait for her in the better land where I trust both you and I will be mercifully sheltered?"

"It cannot be, my child; there is no Time there, and no trouble there."

"You comfort me so much! I am so ignorant. Am I to kiss you now? Is the moment come?"

"Yes."

She kisses his lips; he kisses hers; they solemnly bless each other. The spare hand does not tremble as he releases it; nothing worse than a sweet, bright constancy is in the patient face. She goes next before him—is gone; the knitting-women count Twenty-Two."

"'You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer,' said Miss Pross, 'in her breathing. 'Nevrtheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman.'"

Book III Chapter 14

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Madame Defarge looked coldly at her, and said, "The wife of Evremonde; where is she?"

It flashed upon Miss Pross's mind that the doors were all standing open, and would suggest the flight. Her first act was to shut them. There were four in the room, and she shut them all. She then placed herself before the door of the chamber which Lucie had occupied.

Madame Defarge's dark eyes followed her through this rapid movement, and rested on her when it was finished. Miss Pross had nothing beautiful about her; years had not tamed the wildness, or softened the grimness, of her appearance; but, she too was a determined woman in her different way, and she measured Madame Defarge with her eyes, every inch.

"You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer," said Miss Pross, in her breathing. "Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman."

Madame Defarge looked at her scornfully, but still with something of Miss Pross's own perception that they two were at bay. She saw a tight, hard, wiry woman before her, as Mr. Lorry had seen in the same figure a woman with a strong hand, in the years gone by. She knew full well that Miss Pross was the family's devoted friend; Miss Pross knew full well that Madame Defarge was the family's malevolent enemy.

"On my way yonder," said Madame Defarge, with a slight movement of her hand towards the fatal spot, "where they reserve my chair and my knitting for me, I am come to make my compliments to her in passing. I wish to see her."

"I know that your intentions are evil," said Miss Pross, "and you may depend upon it, I'll hold my own against them."

Each spoke in her own language; neither understood the other's words; both were very watchful, and intent to deduce from look and manner, what the unintelligible words meant.

"It will do her no good to keep herself concealed from me at this moment," said Madame Defarge. "Good patriots will know what that means. Let me see her. Go tell her that I wish to see her. Do you hear?"

"If those eyes of yours were bed-winches," returned Miss Pross, "and I was an English four-poster, they shouldn't loose a splinter of me. No, you wicked foreign woman; I am your match."

Commentary:

In Barnard's sequence, Miss Pross is not a wizened little woman who is an anxious mother hen to her "ladybird," Lucie Manette; rather, early in the sequence, in "And smoothing her rich hair with as much pride", he establishes her as a physically formidable woman, although certainly no great beauty. Now, animated by the power love, she confronts the Tigress of Saint Antoine, the predatory Madame Defarge, cunning, powerful, — and in Dickens's text beautiful:

"Madame Defarge looked coldly at her, and she said, "the wife of Evrémonde; where is she?"

It flashed upon Miss Pross's mind that the doors were all standing open, and would suggest the flight. Her first act was to shut them all. She then placed herself before the door of the chamber which Lucie had occupied.

Thus, Barnard pits against one another two equally matched viragoes, burly, indomitable, and determined. Whereas Dickens describes Madame Defarge as wearing a robe as she makes her way through the streets, Barnard has given pantaloons of the Emilia Bloomer variety, thereby increasing her masculine character. Though slighter and more anxious by nature, Miss Pross as Dickens describes her is formidable in a very different way:

Miss Pross had nothing beautiful about her; years had not tamed the wildness, or softened the grimness, of her appearance; but she, too, was a determined woman in her different way, and she measured Madame Defarge with her eyes, every inch."

John McLenan in the series for the American serialization published in Harper's Weekly chose to focus on the moment in which, the hidden pistol having been discharged, the French woman lies died at the feet of the English woman in "Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground" in the second illustration for 26 November 1859. McLenan's Madame Defarge, a young woman with a beautiful face, lies dead, her pistol still in her grip as a cloud of exploded gunpowder fills the room and the aged, formally dressed Miss Pross holds her hand to her head in token of her sudden deafness. The picture and barley cane-twist chair in the background connect this scene with that in which Doctor Manette returned from his fruitless quest to have his son-in-law released after the trial (the head note to the November 12th installment).

In David O. Selznick's epic 1935 film adaptation, starring Ronald Coleman as Sydney Carton, Edna May Oliver's jingoistic tag line "I am an English woman" sets a triumphant note, and signals her emerging victorious in her wrestling match with the physically powerful Terese Defarge, played with sinister zest by an American actress of Bohemian descent, Blanche Yurka. Throughout this stunning cinematic adaptation, Yurka's Madame Defarge has been more than a match for the evil Marquis St. Evrémonde (Basil Rathbone), but falls, a victim of her own hubris, to the redoubtable English woman (Oliver) in one of those rare moments in cinema that brings down the house. Both Barnard and McLenan realized the emotional impact of the confrontation of these continents of experience, and the palpable triumph of love over hate that the outcome of their struggle for the pistol underscores.

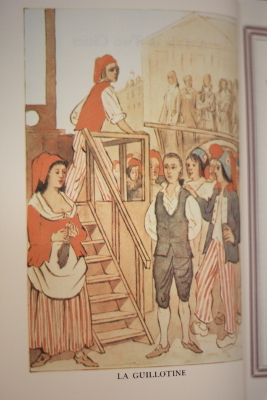

"The Third Tumbrel"

Book III Chapter 15

Fred Barnard

The Household Edition 1870s

Text Illustrated:

"Bad Fortune!" cries The Vengeance, stamping her foot in the chair, "and here are the tumbrils! And Evremonde will be despatched in a wink, and she not here! See her knitting in my hand, and her empty chair ready for her. I cry with vexation and disappointment!"

As The Vengeance descends from her elevation to do it, the tumbrils begin to discharge their loads. The ministers of Sainte Guillotine are robed and ready. Crash!—A head is held up, and the knitting-women who scarcely lifted their eyes to look at it a moment ago when it could think and speak, count One.

The second tumbril empties and moves on; the third comes up. Crash!—And the knitting-women, never faltering or pausing in their Work, count Two.

The supposed Evremonde descends, and the seamstress is lifted out next after him. He has not relinquished her patient hand in getting out, but still holds it as he promised. He gently places her with her back to the crashing engine that constantly whirrs up and falls, and she looks into his face and thanks him.

"But for you, dear stranger, I should not be so composed, for I am naturally a poor little thing, faint of heart; nor should I have been able to raise my thoughts to Him who was put to death, that we might have hope and comfort here to-day. I think you were sent to me by Heaven."

"Or you to me," says Sydney Carton. "Keep your eyes upon me, dear child, and mind no other object."

"I mind nothing while I hold your hand. I shall mind nothing when I let it go, if they are rapid."

"They will be rapid. Fear not!"

The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims, but they speak as if they were alone. Eye to eye, voice to voice, hand to hand, heart to heart, these two children of the Universal Mother, else so wide apart and differing, have come together on the dark highway, to repair home together, and to rest in her bosom."

Commentary:

Sydney Carton's assuming the identity of Charles Darnay in order to save Lucie, her husband, and child requires that he allow himself to be transported to the Guillotine in one of the many tumbrels expropriated by the revolutionary leaders. By coincidence, he shares his final moments with another blameless victim of anti-aristocratic hysteria.

In Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Ch. 15, "The Footsteps Die out Forever," Carton, disguised as the last representative of the infamous Evrémondes, calmly, tenderly takes the hand of the little seamstress whom he met in ch. 13 in order to give her courage, even as the blood-thirsty mob around the cart vilifies them, and The Vengeance scrutinizes him. But Barnard does not include the terrible woman, the spy, the robed ministers of Sainte Guillotine, or legion of knitting-women. Barnard focuses on Carton's tranquil reassurance of his timid companion rather than on the machinations of the plot.

John McLenan, the American illustrator for the Harper's serialization of the novel, also focuses on the courage and tenderness of Carton in his final moments in the final Harper's Weekly installment's "The Two Stand in the Fast-thinning Throng of Victims, etc.". In the American illustration, Carton and the seamstress have already alighted from the cart, and stand on the ground, guarded by heavily armed Jacobins. The moment in both Barnard and McLenan is something of an anti-climax since Miss Pross has already thwarted Madame Defarge's plans in "Like the soul of the furious woman whose body lay lifeless on the ground" in the McLenan sequence, and in "You might, from your appearance, be the wife of Lucifer . . ." in Barnard's.

Change that coat for this of mine

Book III Chapter 13

A. A. Dixon

Collins Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Of all the people upon earth, you least expected to see me?" he said.

"I could not believe it to be you. I can scarcely believe it now. You are not"—the apprehension came suddenly into his mind—"a prisoner?"

"No. I am accidentally possessed of a power over one of the keepers here, and in virtue of it I stand before you. I come from her—your wife, dear Darnay."

The prisoner wrung his hand.

"I bring you a request from her."

"What is it?"

"A most earnest, pressing, and emphatic entreaty, addressed to you in the most pathetic tones of the voice so dear to you, that you well remember."

The prisoner turned his face partly aside.

"You have no time to ask me why I bring it, or what it means; I have no time to tell you. You must comply with it—take off those boots you wear, and draw on these of mine."

There was a chair against the wall of the cell, behind the prisoner. Carton, pressing forward, had already, with the speed of lightning, got him down into it, and stood over him, barefoot.

"Draw on these boots of mine. Put your hands to them; put your will to them. Quick!"

"Carton, there is no escaping from this place; it never can be done. You will only die with me. It is madness."

"It would be madness if I asked you to escape; but do I? When I ask you to pass out at that door, tell me it is madness and remain here. Change that cravat for this of mine, that coat for this of mine. While you do it, let me take this ribbon from your hair, and shake out your hair like this of mine!"

To the guillotine, all aristocrats!

A. A. Dixon

Book III Chapter 15

Collins Edition 1905

Text Illustrated:

"On the steps of a church, awaiting the coming-up of the tumbrils, stands the Spy and prison-sheep. He looks into the first of them: not there. He looks into the second: not there. He already asks himself, "Has he sacrificed me?" when his face clears, as he looks into the third.

"Which is Evremonde?" says a man behind him.

"That. At the back there."

"With his hand in the girl's?"

"Yes."

The man cries, "Down, Evremonde! To the Guillotine all aristocrats! Down, Evremonde!"

"Hush, hush!" the Spy entreats him, timidly.

"And why not, citizen?"

"He is going to pay the forfeit: it will be paid in five minutes more. Let him be at peace."

But the man continuing to exclaim, "Down, Evremonde!" the face of Evremonde is for a moment turned towards him. Evremonde then sees the Spy, and looks attentively at him, and goes his way."

"Sydney Carton and the Little Seamstress"

Book III Chapter 13

Harry Furniss

Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Citizen Evrémonde," she said, touching him with her cold hand. "I am a poor little seamstress, who was with you in La Force."

"He murmured for answer: "True. I forget what you were accused of?"

""Plots. Though the just Heaven knows that I am innocent of any. Is it likely? Who would think of plotting with a poor little weak creature like me?"

"The forlorn smile with which she said it, so touched him, that tears started from his eyes.

""I am not afraid to die, Citizen Evrémonde, but I have done nothing. I am not unwilling to die, if the Republic which is to do so much good to us poor, will profit by my death; but I do not know how that can be, Citizen Evrémonde. Such a poor weak little creature!"

"As the last thing on earth that his heart was to warm and soften to, it warmed and softened to this pitiable girl.

""I heard you were released, Citizen Evrémonde. I hoped it was true?"

""It was. But, I was again taken and condemned."

""If I may ride with you, Citizen Evrémonde, will you let me hold your hand? I am not afraid, but I am little and weak, and it will give me more courage."

"As the patient eyes were lifted to his face, he saw a sudden doubt in them, and then astonishment. He pressed the work-worn, hunger-worn young fingers, and touched his lips."

Commentary:

The extensive caption which J. A. Hammerton has provided points towards Carton's first crucial test in his impersonation of Darnay since the seamstress had become acquainted with "Citizen Evrémonde" during his extended incarceration in La Force. Carton carries off his substitution coolly by prompting the young woman to describe the grounds upon which she was arrested, thereby deflecting conversation from himself. She represents a very real source of suspense since she and Darnay could well have been in close association over fourteen months in La Force. That the date is now November 1793 suggests that Carton will shortly become one of the more than two thousand eight-hundred victims of the Reign of Terror executed at the Place de la Concorde between January 1793 and 3 May 1795 (Sanders 164). In the space of just these few lines of dialogue, Dickens uses the birth-name of Charles Darnay some five times — as if through this repetition and Carton's reaction to it he may let his mask slip. The climax of the dialogue, not in Hammerton's caption for the illustration, is the seamstress's revealing that she, simple as she is, has penetrated the disguise:

"Are you dying for him?" she whispered.

"And his wife and child. Hush! Yes."

"O you will let me hold your brave hand, stranger?"

"Hush! Yes, my poor sister; to the last."

To heighten the suspense, Furniss has placed four armed guards in the darkened communal cell so that, were they not whispering at this point, the conversation between Carton and the seamstress would almost certainly be overheard. In the murky darkness of this general holding cell it is not easy initially for the reader to pick out Carton, but he must be the man to the extreme left, identifiable by the young woman with whom he is in close conversation and by the fact that he — unlike the other male aristocrats in the cell — is not wearing a white-powdered wig (Carton has exchanged a black hair-ribbon with Darnay earlier, and now wears his "Brutus" hairstyle tied back to emphasize his likeness to Darnay).

Since the reader examines the picture proleptically, undoubtedly he or she would revert to it, so that it serves as a suitable complement to the letterpress. The lithograph conveys effectively the atmosphere of despair that grips the prisoners, among whom one is momentarily in the light at the back, apparently waving to somebody. Furniss has not shown all fifty-two people in today's batch consigned to the guillotine, but has selected nine whose postures betoken their emotional responses to the situation. The bayonets glinting in the darkness reveal the presence of five uniformed guards, implying that escape is unlikely. The chiaroscuro is intensified by the presence of just one source of light, which filters through the darkness, highlighting the wigs of the male prisoners and thereby emphasizing their difference from Carton, who, despite the fact that his is the largest figure in the composition, remains muffled in the darkness, his face not detectable in any detail. The picture is rendered more interesting by virtue of the extreme depth of field, by which Furniss positions the reader even further inside the condemned cell and away from the light.

A mere "bit part" in the novel, the seamstress was a named part in the Victorian stage adaptations, a fact that suggests she actually played a significant role in these final scenes:

The Only Way was produced at the Lyceum on February 16th, 1899, and the occasion launched [the lead actor] Martin-Harvey as one of the great actor-managers of his day. It was a drama, vital and moving, and his sensitive portrayal of Sydney Carton a creation of romance outstanding in the theatre. . . . . Included in the supporting cast that memorable first night at the Lyceum were Herbert Sleath as Charles Darnay, Holbrook Blinn as Ernest Defarge, Grace Warner as Lucie Manette and the veteran actress, Alice Marriott, a one-time Hamlet, as The Vengeance. Nina de Silva played Mimi, so the anonymous seamstress of the novel was called, and played the part during every one of the ten revivals in the town [i. e., the West End of London], the last being at the Savoy Theatre, November 7th, 1930. [Morley, 39]

Malcolm Morley's analysis reveals that the celebrated stage adaptation emphasized certain characters that today's novel reader would classify as minor, including The Vengeance and the seamstress, diametrical opposites caught up in the tide of Revolution. Almost certainly Furniss would have attended at least one performance of The Only Way prior to his work on the Charles Dickens Library Edition, and therefore may have been influenced by the play in his characterizations of The Vengeance, who appears in a number of his historical "dark" plates, and the seamstress, to whom he has given prominence in this final dark plate.

"Struggle between Miss Pross and Madame Defarge"

Book III Chapter 14

Harry Furniss

Charles Dickens Library Edition 1910

The commentary for this illustration is so long it will probably take me more than one - or two - posts to get it all. So here it begins:

Commentary:

Whereas Dickens's original illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, probably in conjunction with the author in order not to telegraph the dramatic conclusion to the reader of the monthly parts in advance of that reader's encountering the passage in the accompanying text, avoided the scenes in which Sydney Carton meets his death on the scaffold disguised as Charles Darnay and Miss Pross's love for Lucie proves stronger than Madame Defarge's hatred of the Evrémondes, Harry Furniss has depicted both highly dramatic scenes — even if he has made Carton on the Scaffold the volume's frontispiece.

Although the murky "dark plate" of Carton and the innocent victim of an arbitrary judgment awaiting transportation in the Conciergerie, Sydney Carton and the little Seamstress makes little impression initially, the wrestling match between the two determined viragoes suitably pits the avenging against the protective angel, although the picture is situated after the outcome of this life-and-death grappling in the letterpress. Good as the illustration is in its depiction of these female (but not feminine) Titans, it cannot match the sentimental force of Dickens's description of this mortal combat, and the effectiveness of the dialogue:

"Nevertheless, you shall not get the better of me. I am an Englishwoman."

Each spoke in her own language; neither understood the other's words; both were very watchful, and intent to deduce from look and manner, what the unintelligible words meant.

Set in the deserted rooms of Tellson's Paris headquarters, this is the climactic scene in many of the film adaptations, as it pits the supremely cunning and physically powerful Térèse Defarge, married as much to the bitterness at having lost her entirely family as to Ernest Defarge — and mother only to her lifelong grudge against the destroyers of her family — against the stolid Miss Pross, resolute protector of her "Ladybird." In the 1935 David O. Selznick film, Madame Defarge, the ardent but somewhat hag like sans culotte played with passionate and menacing conviction by forty-eight-year-old Blanche Yurka, has heretofore been unstoppable, but in Miss Pross (played in that same film by fifty-two-year-old Edna May Oliver), whom Dickens establishes as an avowed monarchist and stalwart Briton, the vengeful spirit of Revolution has met her match. Viewed even seventy-five years later, this scene (at least in their minds) brings viewers to their feet, cheering for the victory that ensures the escape of the Darnays. The Furniss illustration effectively realizes the mighty conjunction of these binary opposites in a Dickensian clash of the Titans........

.....Already in The Perils of Certain English Prisoners in the extra-Christmas Number of Household Words for 1857 we have seen a virulent strain of xenophobia and racism, Dickens's extreme response to the Sepoy Mutiny, but these biases manifest themselves here quite differently as Miss Pross and her Satanic opposite are not entirely uni-dimensional characters whom we have heretofore detested or approved of, Madame Defarge having on her side a compelling argument for the destruction of the aristocracy that does not equate with the low, villainous Christian George King's unmitigated perfidy in the Collins-Dickens novella of 1857. Each of these female antagonists in the 1859 serial is, in fact, what Lisa Robson has termed "a feminine aberration" in that Miss Pross is a peculiar combination of subservience (to her scapegrace brother Solomon as well as to her employer, Lucie) and aggression, while Madame Defarge is a married woman without children who runs a business, consorts with and even directs the men of the Jacquerie, and is consumed by a most unfeminine blood lust. Although both give "faithful service" to their convictions, in this ultimate scene there is never a moment in which the reader identifies here with the blood-thirsty Frenchwoman against the innocent Briton, previously not much more than a crotchety "stereotypical Victorian old maid", despite her red hair, who has already stridently broadcast her pride in being a British subject, even in the midst of the Reign of Terror, when such protestations might result in arbitrary arrest:

"For gracious sake, don't talk about Liberty; we have quite enough of that," said Miss Pross.

"Hush, dear! Again?" Lucie remonstrated.

"Well, my sweet," said Miss Pross, nodding her head emphatically, "the short and the long of it is, that I am a subject of His Most Gracious Majesty King George the Third;" Miss Pross curtseyed at the name; and as such, my maxim is, Confound their politics, Frustrate their knavish tricks, On him our hopes we fix, God save the King!" [a now little-sung verse from the 1745 version of "God Save the King!"]

Indeed, Catherine Waters' interpretation emphasizes Dickens's investing Miss Pross with the national attributes of the English as she closes in mortal combat with her Gallic opposite, but her wiry strength and characterization as a decidedly English grotesque also make her a fit opponent for Madame Defarge. While Madame Defarge represents a repudiation of the ideals Miss Pross so vigilantly protects in the person of her 'Ladybird', it is primarily the national differences between the two women that determine their fateful encounter. As the two of them are set face to face in the narrative, other categories of difference — gender, generational and class difference — are ostensibly overridden by the opposition of nationalities. What distinguishes the struggle between Madame Defarge and Miss Pross is not its commonly proclaimed thematic function as a 'contest between the forces of hatred and love', but its characterization as a confrontation between France and England.

Intuitively, Furniss apprehends and communicates this "national difference" in Miss Pross's stubborn defiance of the female Lucifer as this crusty, old maid in a proper eighteenth-century English spinster's cap stares down her muscular adversary in the Phrygian cap, the outward and visible sign of her rebellious spirit. Perhaps to exonerate her of the charge of manslaughter, Furniss has Miss Pross in a defensive posture as Madame Defarge swings wide and lunges forward. Only their dresses imply their gender: their faces and arms are thoroughly masculine, and this fight to the death seems utterly out of place in the domestic setting, characterized by the broken porcelain basin in the foreground. Several other illustrators, including Phiz and Eytinge, have interpreted Miss Pross as a mere old maid, albeit one of stubborn and protective disposition, whose victory at this crucial juncture therefore must be a matter of chance — or, perhaps, Providence, which Dickens in his 5 June 1860 letter to Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton expressed himself as being quite justified in using here:

"I am not clear, and I never have been clear, respecting that canon of fiction which forbids the interposition of accident in such a case as Madame Defarge's death. Where the accident is inseparable from the passion and emotion of the character, where it is strictly consistent with the whole design, and arises out of some culminating proceeding on the part of the character which the whole story had led up to, it seems to me to become, as it were, an act of divine justice. And when I use Miss Pross (though this is quite another question) to bring about that catastrophe, I have the positive intention of making that half-comic intervention a part of the desperate woman's failure, and of opposing that mean death — instead of a desperate one in the streets, which she wouldn't have minded — to the dignity of Carton's wrong or right; this was the design, and seemed to be in the fitness of things."

However, perhaps neither Barnard nor Furniss was comfortable with the notion that Madame Defarge is the victim of mere caprice or accident (or for that matter Providence) in that these later artists made Miss Pross as physically formidable as her adversary, whereas Phiz, Eytinge, and McLenan have made her a far less imposing figure and therefore the victor by virtue of the fortunate accident of her discharging Madame Defarge's own pistol, a symbol of her expropriation of masculine power. Even as she contemplates betraying her own husband (whom she, like Lady Macbeth with respect to her husband's murdering the venerable King Duncan in Shakespeare's tragedy of bloody ambition, dismisses as too tender-hearted about Doctor Manette to consign him, his child, and grandchild to the guillotine) and arranging the execution of both Lucie and her child on trumped-up charges, she perishes in a burst of gunpowder by inadvertence caused by her own negligence in the care and storage of a destructive implement more properly from the political, martial, and therefore masculine sphere.

Having abandoned her knitting-needles for weapons of close combat, Madame Defarge, too, changes over the period encompassed by these illustrated editions, that is, 1859 to 1910, as a number of critics have noted:

Madame Defarge begins to age soon after Dickens' death. The "Household Edition" (New York: Harper, 1878), for example, shows a square-jawed, muscular Madame Defarge, looking very much like a man, on the title page. She looks older, heavier, and uglier by the end of the novel, but is at her worst where she bears a remarkable resemblance to the aging Queen Victoria.

In asserting that illustrators' conceptions of Madame Defarge began to shift in the 1870s, Catherine Waters overlooks the more conventional depictions of her as a not-unattractive publican earlier in the story as realized by Fred Barnard and Harry Furniss:

In the original 'Phiz' drawings, she is shown as a strong, young woman, with a beautiful but determined face, and dark hair. The illustrations set her in contrast with the blonde-haired beauty of Lucie Manette. However, many subsequent versions of Madame Defarge in film and illustration have made her a witch. According to Hutter, the Harper and Row cover to A Tale of Two Cities, for example, 'shows a cadaverous old crone, gray-haired, hunched over her knitting, with wrinkles stitched across a tightened face'. In the 1935 film, starring Ronald Colman, Madame Defarge is a rather haggard and plain-faced woman, with dark circles beneath her eyes, whose grim appearance contrasts with the fair complexion and rosy lips of the beautiful Lucie.

This change in the visual representation of Madame Defarge denotes a cultural shift in the construction of female subjectivity from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, and highlights Defarge's function in the novel. As a crucial part of the novel's effort to solve the problems posed by the Revolution, Madame Defarge serves as the monstrous female 'other' against which the norms of Victorian middle-class femininity and domesticity can be invoked. She is characterized as dangerously sexual and violent, oblivious of her wifely role and domestic responsibilities, lacking the feminine virtues of meekness, compassion and purity shown by Lucie and ominously intimate with like-minded women. All of these traits are informed by a Victorian middle-class conception of female subjectivity. Later representations showing Madame Defarge as a witch provide evidence of a historical change in the significance of femininity and domesticity as a cultural norms. "In order to continue serving as the 'other' woman, Madame Defarge is represented as old, ugly and deformed, because overt sexual attractiveness, assertiveness and freedom from convention have become attributes of the new twentieth-century heroine........

"For gracious sake, don't talk about Liberty; we have quite enough of that," said Miss Pross.

"Hush, dear! Again?" Lucie remonstrated.

"Well, my sweet," said Miss Pross, nodding her head emphatically, "the short and the long of it is, that I am a subject of His Most Gracious Majesty King George the Third;" Miss Pross curtseyed at the name; and as such, my maxim is, Confound their politics, Frustrate their knavish tricks, On him our hopes we fix, God save the King!" [a now little-sung verse from the 1745 version of "God Save the King!"]

Indeed, Catherine Waters' interpretation emphasizes Dickens's investing Miss Pross with the national attributes of the English as she closes in mortal combat with her Gallic opposite, but her wiry strength and characterization as a decidedly English grotesque also make her a fit opponent for Madame Defarge. While Madame Defarge represents a repudiation of the ideals Miss Pross so vigilantly protects in the person of her 'Ladybird', it is primarily the national differences between the two women that determine their fateful encounter. As the two of them are set face to face in the narrative, other categories of difference — gender, generational and class difference — are ostensibly overridden by the opposition of nationalities. What distinguishes the struggle between Madame Defarge and Miss Pross is not its commonly proclaimed thematic function as a 'contest between the forces of hatred and love', but its characterization as a confrontation between France and England.

Intuitively, Furniss apprehends and communicates this "national difference" in Miss Pross's stubborn defiance of the female Lucifer as this crusty, old maid in a proper eighteenth-century English spinster's cap stares down her muscular adversary in the Phrygian cap, the outward and visible sign of her rebellious spirit. Perhaps to exonerate her of the charge of manslaughter, Furniss has Miss Pross in a defensive posture as Madame Defarge swings wide and lunges forward. Only their dresses imply their gender: their faces and arms are thoroughly masculine, and this fight to the death seems utterly out of place in the domestic setting, characterized by the broken porcelain basin in the foreground. Several other illustrators, including Phiz and Eytinge, have interpreted Miss Pross as a mere old maid, albeit one of stubborn and protective disposition, whose victory at this crucial juncture therefore must be a matter of chance — or, perhaps, Providence, which Dickens in his 5 June 1860 letter to Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton expressed himself as being quite justified in using here:

"I am not clear, and I never have been clear, respecting that canon of fiction which forbids the interposition of accident in such a case as Madame Defarge's death. Where the accident is inseparable from the passion and emotion of the character, where it is strictly consistent with the whole design, and arises out of some culminating proceeding on the part of the character which the whole story had led up to, it seems to me to become, as it were, an act of divine justice. And when I use Miss Pross (though this is quite another question) to bring about that catastrophe, I have the positive intention of making that half-comic intervention a part of the desperate woman's failure, and of opposing that mean death — instead of a desperate one in the streets, which she wouldn't have minded — to the dignity of Carton's wrong or right; this was the design, and seemed to be in the fitness of things."

However, perhaps neither Barnard nor Furniss was comfortable with the notion that Madame Defarge is the victim of mere caprice or accident (or for that matter Providence) in that these later artists made Miss Pross as physically formidable as her adversary, whereas Phiz, Eytinge, and McLenan have made her a far less imposing figure and therefore the victor by virtue of the fortunate accident of her discharging Madame Defarge's own pistol, a symbol of her expropriation of masculine power. Even as she contemplates betraying her own husband (whom she, like Lady Macbeth with respect to her husband's murdering the venerable King Duncan in Shakespeare's tragedy of bloody ambition, dismisses as too tender-hearted about Doctor Manette to consign him, his child, and grandchild to the guillotine) and arranging the execution of both Lucie and her child on trumped-up charges, she perishes in a burst of gunpowder by inadvertence caused by her own negligence in the care and storage of a destructive implement more properly from the political, martial, and therefore masculine sphere.

Having abandoned her knitting-needles for weapons of close combat, Madame Defarge, too, changes over the period encompassed by these illustrated editions, that is, 1859 to 1910, as a number of critics have noted:

Madame Defarge begins to age soon after Dickens' death. The "Household Edition" (New York: Harper, 1878), for example, shows a square-jawed, muscular Madame Defarge, looking very much like a man, on the title page. She looks older, heavier, and uglier by the end of the novel, but is at her worst where she bears a remarkable resemblance to the aging Queen Victoria.

In asserting that illustrators' conceptions of Madame Defarge began to shift in the 1870s, Catherine Waters overlooks the more conventional depictions of her as a not-unattractive publican earlier in the story as realized by Fred Barnard and Harry Furniss:

In the original 'Phiz' drawings, she is shown as a strong, young woman, with a beautiful but determined face, and dark hair. The illustrations set her in contrast with the blonde-haired beauty of Lucie Manette. However, many subsequent versions of Madame Defarge in film and illustration have made her a witch. According to Hutter, the Harper and Row cover to A Tale of Two Cities, for example, 'shows a cadaverous old crone, gray-haired, hunched over her knitting, with wrinkles stitched across a tightened face'. In the 1935 film, starring Ronald Colman, Madame Defarge is a rather haggard and plain-faced woman, with dark circles beneath her eyes, whose grim appearance contrasts with the fair complexion and rosy lips of the beautiful Lucie.

This change in the visual representation of Madame Defarge denotes a cultural shift in the construction of female subjectivity from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, and highlights Defarge's function in the novel. As a crucial part of the novel's effort to solve the problems posed by the Revolution, Madame Defarge serves as the monstrous female 'other' against which the norms of Victorian middle-class femininity and domesticity can be invoked. She is characterized as dangerously sexual and violent, oblivious of her wifely role and domestic responsibilities, lacking the feminine virtues of meekness, compassion and purity shown by Lucie and ominously intimate with like-minded women. All of these traits are informed by a Victorian middle-class conception of female subjectivity. Later representations showing Madame Defarge as a witch provide evidence of a historical change in the significance of femininity and domesticity as a cultural norms. "In order to continue serving as the 'other' woman, Madame Defarge is represented as old, ugly and deformed, because overt sexual attractiveness, assertiveness and freedom from convention have become attributes of the new twentieth-century heroine........

.........In fact, in this final illustration of these champions of traditional (English) and radicalized (French) societies, Furniss has depicted these combatants in a manner quite inconsistent with his earlier representations of them: in Miss Manette and Mr. Lorry Interrupted and Doctor Manette's 'Old Companion' Furniss underscores Miss Pross's propensity to act rather than passively acquiesce in male decisions, but the slight if somewhat assertive servant in these earlier illustrations bears little resemblance to the powerful wrestler here. In many ways, it seems as if Furniss has derived this British bulldog version of Miss Pross directly from Fred Barnard, who from the first regards Miss Pross's assertiveness in the scene at the Royal George as a sign of her masculine character, so that he introduces her not as the "slight," and generally somewhat timid servant-woman of Phiz's illustrations, but as a large, strong-boned, broad-shouldered woman with masculinised facial features in And smoothing her rich hair with as much pride as she could possibly have taken in her own hair if she had been the vainest and handsomest of women, the illustration accompanying Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter 6, "Hundreds of People." Since Barnard depicts Miss Pross only twice, he initially suggests that she is both feminine (a surrogate mother who is taking pride in her adopted child's golden hair) and masculine (physically as well as emotionally domineering) in order later on to make her more plausible as a match for the French termagant, who is both a far cry from his own coolly competent community organizer of Saint Antoine in "Still Knitting" and Phiz's original conception of a beautiful, demure knitter who is blonde Lucie Manette's brunette doppelganger in Phiz's wine-shop scenes and the monthly wrapper:

Madame Defarge in "The Wine-Shop" resembles Lucie "After the Sentence" and during "The Knock at the Door"; Lucie's expressions are naturally quite different, but the features of the two women are quite similar — both women are young and attractive. What appear to be mirror images of the two women are placed opposite each other on the wrapper of the original edition.

Whereas Phiz is able to maintain Madame Derfarge's fine, female figure in The Sea Rises, his title for the violent post-Bastille scene in which the Saint Antoine mob, whipped up to a frenzy by Madame Defarge and her companion, The Vengeance, abuse and then hang Foulon, functionary of the ancient régime, Barnard wisely decides to leave the fair publican out of the picture altogether. Thus, we can put Furniss's depiction of the mighty female adversaries as the novel's concluding illustration (rather than the scene of Carton disguised as Darnay on the public scaffold, which Furniss has strategically made the frontispiece in order to end his visual program on a note of triumph rather than of tragedy) in the context of the Household Edition volume of 1874, in which the ultimate and therefore climatic illustration focuses on the sacrifice of Sydney Carton in The Third Tumbrel rather than the accidental triumph of Miss Pross's English tenacity and devotion to a living family over Madame Defarge's French passion and commitment to seeking vengeance for those destroyed by an oppressive system and the vicious sociopaths whom it has fostered. Only in Furniss's sequence when she shifts from feminine plotting and enabling masculine action to becoming an active abettor of institutional injustice and class warfare does Furniss transform her from the determined but not unattractive petite bourgeois of The Fountain — An Allegory and Still Knitting into the formidable wrestler (still wearing her tricolor rosette, but now on a Phrygian cap) with the masculine profile and kinetically charged, lean body that occupies most of the frame as she determinedly attempts to push her English opponent out of the frame.....

and that's the end.

Madame Defarge in "The Wine-Shop" resembles Lucie "After the Sentence" and during "The Knock at the Door"; Lucie's expressions are naturally quite different, but the features of the two women are quite similar — both women are young and attractive. What appear to be mirror images of the two women are placed opposite each other on the wrapper of the original edition.

Whereas Phiz is able to maintain Madame Derfarge's fine, female figure in The Sea Rises, his title for the violent post-Bastille scene in which the Saint Antoine mob, whipped up to a frenzy by Madame Defarge and her companion, The Vengeance, abuse and then hang Foulon, functionary of the ancient régime, Barnard wisely decides to leave the fair publican out of the picture altogether. Thus, we can put Furniss's depiction of the mighty female adversaries as the novel's concluding illustration (rather than the scene of Carton disguised as Darnay on the public scaffold, which Furniss has strategically made the frontispiece in order to end his visual program on a note of triumph rather than of tragedy) in the context of the Household Edition volume of 1874, in which the ultimate and therefore climatic illustration focuses on the sacrifice of Sydney Carton in The Third Tumbrel rather than the accidental triumph of Miss Pross's English tenacity and devotion to a living family over Madame Defarge's French passion and commitment to seeking vengeance for those destroyed by an oppressive system and the vicious sociopaths whom it has fostered. Only in Furniss's sequence when she shifts from feminine plotting and enabling masculine action to becoming an active abettor of institutional injustice and class warfare does Furniss transform her from the determined but not unattractive petite bourgeois of The Fountain — An Allegory and Still Knitting into the formidable wrestler (still wearing her tricolor rosette, but now on a Phrygian cap) with the masculine profile and kinetically charged, lean body that occupies most of the frame as she determinedly attempts to push her English opponent out of the frame.....

and that's the end.

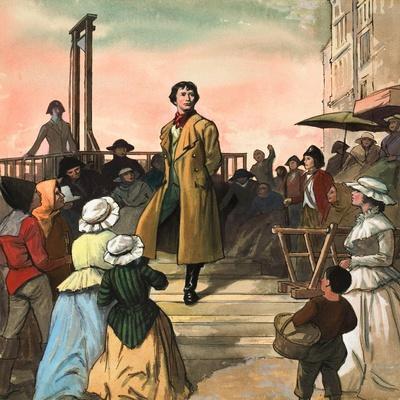

"Sydney Carton on the Scaffold"

Book III Chapter 15

Harry Furniss

Charles Dickens Library Edition 1910

Text Illustrated:

"She kisses his lips; he kisses hers; they solemnly bless each other. The spare hand does not tremble as he releases it; nothing worse than a sweet, bright constancy is in the patient face. She goes next before him — is gone; the knitting-women count Twenty-Two.

"I am the Resurrection and the Life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die."

The murmuring of many voices, the upturning of many faces, the pressing on of many footsteps in the outskirts of the crowd, so that it swells forward in a mass, like one great heave of water, all flashes away. Twenty-Three.