Library of Congress's Blog

September 9, 2025

Justice Barrett Offers Insight Into Court’s Inner Workings

Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett took the stage early Saturday morning at the National Book Festival to talk about her new book, “Listening to the Law: Reflection on the Court and Constitution,” to a crowd that filled a ballroom.

She was the first justice to speak at the book festival since Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the justice she replaced on the nation’s top court.

Interviewed onstage by festival co-Chairman David M. Rubenstein, Barrett said she wrote the book so that Americans could see how the court works and to “feel pride” as the nation approached its 250th birthday.

“The drafting of the Constitution has been called the ‘Miracle at Philadelphia,’” she said, referring to the city in which the document was debated and signed in 1787. “And I think it really was a miracle … it has lasted because each generation has taken it and made it its own.”

Barrett, 53, was a Notre Dame law professor and serving on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Indiana when she was nominated to the Supreme Court by President Trump in 2020, just weeks before the presidential election. (She had been a finalist in 2018, after the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy.)

Trump, when introducing her as his nominee, described her as “one of our nation’s most brilliant and gifted legal minds.”

Born in New Orleans, she was the oldest of seven children and now has seven children with her husband, Jesse Barrett. She obtained her law degree at Notre Dame (meeting her husband in the process) and, she told the crowd, the family was happy there before her nomination.

“My husband and I have plots at Notre Dame in the cemetery there,” she said, “so I really thought that’s where we were going to stay.”

Her conversation Saturday morning touched on how she comes to her decisions, indicating it’s not a cut and dried process.

“I try to keep an open mind,” she said. “One thing I try to communicate in this book is that every step of the decision-making process is really important and it matters. So, I go into (judicial) conference knowing what I think, but I do listen to my colleagues, and I will adjust what I think about how we should approach the opinion based on what my colleagues say.”

Justice Barrett also provided the audience with details about the daily business of the court.

The justices do not discuss cases before oral arguments; sometimes the oral arguments are so good they can cause her to change her mind about at least part of her opinion; one of her four clerks writes the first draft of her opinions, then she rewrites and edits as needed; when her opinion is circulated among justices, sometimes a fellow justice will ask for a small change before signing on; and, finally, the most recent justice has to oversee the court’s cafeteria and open the door when someone knocks during their discussions.

Another book while she’s on the bench isn’t in the offing, she said, calling the publication a “one and done.” She had to find time over the past several summers to write while the court was in recess, she said, and free time is at a premium.

“It was an arduous process writing the book, to be honest,” she said with a smile, drawing a laugh from the crowd. “I’m not sure I would repeat it just because it did take so long. I have seven children and another job.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 8, 2025

The Library’s 2025 Literacy Award Winners

This is a guest post by Judith Lee, the Literary Awards program manager.

In 1973, volunteers set up a modest literacy program in New York City, working to help parents and their children gain reading skills to improve their lives in a foundational way. Over the decades, Literacy Partners grew into a nonprofit with more than 30 full-time staffers in eight states and Puerto Rico.

Today, 52 years later, the program’s two-generation approach won the Library of Congress’ top honor in the 2025 Literacy Awards, the $150,000 David M. Rubenstein Prize, bringing the organization resources and national acclaim.

Acting Librarian of Congress Robert Newlen made the announcement today — World Literacy Day — awarding the annual program’s four top prize winners and 20 honorees. The groups were awarded a total of $525,000, all going to literacy-building nonprofits working around the world, and all funded by philanthropic donations.

“The 2025 winners and honorees have demonstrated a commitment not only to individuals but also the communities in which they live,” Newlen said.

For agencies that often work in low-income and difficult circumstances, the awards and recognition hit home.

“We are deeply honored to have our work recognized by the Library of Congress,” said Kristine Cooper, Literacy Partner’s chief external affairs officer. “This recognition affirms not only the strength of our mission, but also the lasting impact literacy has on generations to come.”

In Memphis, Tennessee, Literacy Mid-South received the $100,000 Kislak Family Foundation prize for its outsized impact on literacy development relative to its small size.

The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for their outstanding work. Photo courtesy of Prime Time.

The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for their outstanding work. Photo courtesy of Prime Time.In New Orleans, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ Prime Time Reading Program received the $50,000 American Prize for equipping families with the tools and habits to make reading a shared and enriching part of daily life.

Finally, Building Tomorrow, a former Literacy Award Successful Practices Honoree, received the $50,000 International Prize for teaching literacy and increasing access to education in Uganda. The program has been such a success that it recently expanded into Rwanda.

“Building Tomorrow was a proud Successful Practices Honoree in 2023, and receiving this even greater recognition in 2025 is a humbling validation of the momentum building around community-powered education,” said George Srour, Building Tomorrow’s co-founder.

The Library’s Literacy Awards, established in 2013 with Rubenstein’s support (and bolstered by the Kislak Family Foundation in 2023) has awarded 247 prizes, totaling more than $4.3 million. More than 200 organizations from 42 countries have been recognized for their work.

Nonprofit organizations, schools, libraries and literacy initiatives from across the country and around the world apply for the awards every January. The 15-member Literacy Awards Advisory Board then reviews the applications before the Librarian of Congress makes the final decisions.

This year’s other international honorees were in Kenya, Scotland, Nigeria and South Africa. There were 15 other U.S. honorees, ranging from locally focused efforts to nationwide campaigns.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

September 3, 2025

Cassandra Gardner: “Life is Too Short Not to Enjoy Yourself”

Cassandra Gardner is an administrative specialist in the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate. She is retiring this month after a 40-year career at the Library. Sahar Kazmi conducted this interview.

Tell us about your background.

I was born and raised in Maryland and attended Prince George’s County schools. My parents bought their first house two years before I was born, and I still live in that house. I’m the only person I know who has never moved in their lifetime.

What brought you to the Library?

I was a work-study student at Northwestern High School in 1985. I would go to school for four hours, leave and then go to the Library and work for four hours. I was offered a permanent job after graduation. Little did I know that I would spend the rest of my work career here. I started as a clerk in the Copyright Office. I stayed there for four years until I accepted a position in what was then called Library Services. Library Services is now Library Collections and Services Group, and I work in the Acquisitions, Fiscal and Support Section as an administrative specialist. In my current position, I’m responsible for all administrative duties in AFOS, which include time and attendance, travel, entering performance documents, etc. I also assist the director of the Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access Directorate and the chief of the Network Development and MARC Standards Office with hiring actions such as submitting vacancy requests, scheduling interviews and initiating onboarding activities.

What achievements are you most proud of?

I’m most proud of being here for 40 years and forming lifelong friendships. I’m also proud of all the outstanding appraisals I’ve received and the awards for my performance throughout the years.

What are some standout moments from your time at the Library?

My standout moments are milestones that I made for myself. Before retiring, I wanted to be a seat filler at the Gershwin Prize, attend a Nationals game on Library Night and volunteer at the National Book Festival. I’m proud to say I’ve done all three! I’ve also enjoyed working with the Library’s overseas offices and being able to go to the different embassies here in D.C. to apply for visas for the field directors and for Library employees that had to travel to the field offices on business.

What’s next for you?

As a lifelong Redskins/Commanders fan, I will be going to Atlanta for the Commanders/Falcons game in September. In the immediate future after retirement, I have trips planned to Nashville, Connecticut, Las Vegas to see the New Kids on the Block’s residency and a cruise to Aruba and Curacao. I’m also looking forward to not having to wake up at 4:30 a.m. for work. Next year, I will look for a parttime job to give me something to do while also earning travel and casino money. Life is too short not to enjoy yourself.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 28, 2025

Visit a Library of Wonders

With an introduction by Page Harrington, chief of the Visitor Engagement Office, this is a guest post by several members of that office. It also appears in the July-August issue Library of Congress Magazine.

The nation’s capital is a visitor’s delight: Few places in the United States, if any, pack so many binge-worthy historical and cultural sights into such a compact area.

And few places in Washington, if any, can match the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building for sheer beauty and inspiration. The Jefferson opened in 1897 as the Library’s first stand-alone building, the largest library building in the world. Its dazzling decoration and soaring architecture made it a source of national pride, and its program of sculpture and painting made it a monument to civilization, imagination and knowledge. It’s easy to find out how to visit us, and we hope you do.

Meanwhile, here are some of the VEO staff favorites.

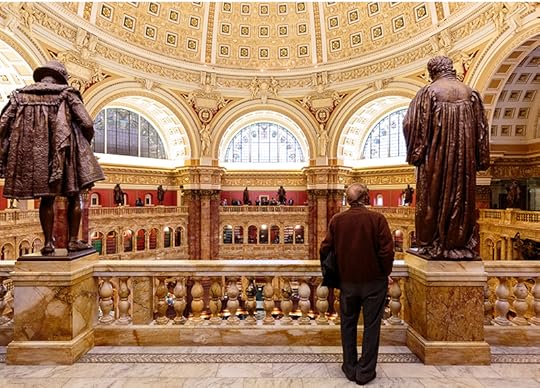

Main Reading Room Statues A visitor stands on the balcony of the Main Reading Room, flanked by two statues. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A visitor stands on the balcony of the Main Reading Room, flanked by two statues. Photo: Shawn Miller.One of the most impressive features of the Main Reading Room are the statues that adorn the room’s balconies and columns. Atop each of the eight marble columns surrounding the room stands a 10-foot allegorical figure representing an area of thought: religion, commerce, history, art, philosophy, poetry, law and science.

These allegorical figures are draped in symbolic clothing and props to communicate their discipline: The history figure holds a book and a mirror facing backward to reflect the past; science holds a globe and a mirror facing forward to reflect progress.

Each figure is flanked by bronze statues (16 in total) representing major contributors to that field. Beethoven, for example, stands on one side of art and Michelangelo on the other.

Together, these symbolic and representative statues convey an 1897 perspective on global contributions to eight core disciplines of knowledge.

—Colette Combs, Visitor Engagement Technician

“Evolution of the Book” John White Alexander’s “Printing Press” mural in the Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.

John White Alexander’s “Printing Press” mural in the Jefferson Building. Photo: Shawn Miller.On the east side of the Great Hall, you will see six lunette paintings that make up “The Evolution of the Book,” by com American painter John White Alexander in 1895.

The series begins on the south end with “The Cairn,” depicting an ancient civilization building a ceremonial mound to commemorate its dead or mark an important location. “Oral Tradition” and “Egyptian Hieroglyphics” follow, portraying early storytelling in two forms. In “Oral Tradition,” a storyteller speaks to a crowd; in “Egyptian Hieroglyphics,” two figures chisel written words into a building exterior.

The north side of the Great Hall houses “Picture Writing,” which shows Native Americans drawing on animal hides that could be easily transported and traded. Finally, “Manuscript Book” and “Printing Press” work in tandem to portray how Johannes Gutenberg revolutionized book production with the creation of metal movable type.

—Shannon McMaster, Visitor Engagement Technician

Minerva Mosaic The Mosaic of Min

erva

, by Elihu Vedder, is on the seccond floor and east corridor of the Jefferon Building. It is within an central arched panel leading to the visitor’s gallery. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The Mosaic of Min

erva

, by Elihu Vedder, is on the seccond floor and east corridor of the Jefferon Building. It is within an central arched panel leading to the visitor’s gallery. Photo: Shawn Miller.In vibrant mosaic tiles, Minerva, the Roman goddess of learning, knowledge and defensive warfare, stands atop the staircase outside the Main Reading Room.

She is at peace: Her spear points to the ground, and her helmet and shield lie at her feet. If there’s peace, learning can advance. In her left hand, Minerva holds a scroll that lists fields of study important to civilization. The scroll is not fully unfurled, suggesting that we always are adding new fields of study to what we consider important.

Just behind sits Minerva’s owl. We all know the owl to be a symbol of wisdom. I like to think this is because an owl can turn its head 270 degrees. It is constantly learning new pieces of information, adding them to its fund of knowledge and changing its mind when called for — this is what makes it wise.

—Rod Woodford, volunteer specialist

Stained-glass Ceiling The ceiling in the Great Hall. Photo: Shawn Miller.

The ceiling in the Great Hall. Photo: Shawn Miller.When you are in the Great Hall, look up at the stained-glass windows of the ceiling. These six beautiful, Tiffany-era glass suns reflect the mosaic on the floor below.

Surrounding the glass, you see metallic leaf. Often mistaken for silver, this is actually aluminum. During the construction of the Jefferson Building, aluminum was rare because of the electricity required to produce it, making it one of the most valuable metals in the world.

Adding to the opulence of the Jefferson Building, aluminum leaf was used alongside gold leaf to accent the Great Hall artwork.

—Danielle Brown, Visitor Engagement Technician

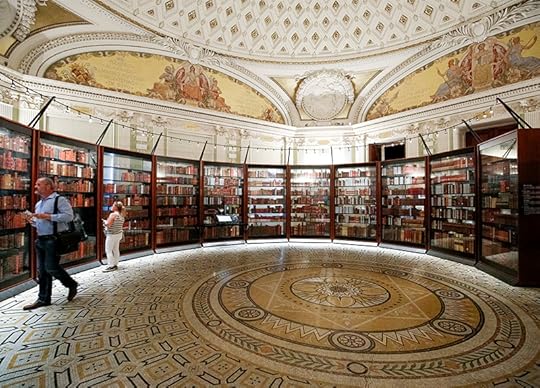

Thomas Jefferson’s Library Thomas Jefferson’s personal library, carefully preserved but on public view, is one of the Library’s most popular exhibits. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Thomas Jefferson’s personal library, carefully preserved but on public view, is one of the Library’s most popular exhibits. Photo: Shawn Miller. Thomas Jefferson’s personal library is an essential part of the Library’s early history — and, today, it’s one of our most sought-out exhibitions.

British troops burned the Capitol Building in 1814, destroying the Library and all of its holdings. The following year, Congress purchased 6,487 books from Jefferson for $23,950 to help rebuild the Library’s collections.

Then, in 1851, devastating fire then destroyed two-thirds of those books. But the remaining volumes are on permanent display today in the building named after Jefferson, allowing visitors to see what is considered the core foundation of the Library’s modern-day collections.

As you go around the circular room, be sure to note some of Jefferson’s interests in literature, including books on beekeeping and winemaking!

—Jessica Castelo, Visitor Engagement Technician

“Touch History” Tours A docent assists visitors on a “touch history” tour of the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller.

A docent assists visitors on a “touch history” tour of the Library. Photo: Shawn Miller. You can also experience the Library through a sense of touch – visually impaired visitors get a sense of the Jefferson Building’s grandeur through our “Touch History” tours.

In the Great Hall, tactile learning opportunities abound: incised brass sun and zodiac symbols embedded in the floor, smooth busts of Thomas Jefferson and George Washington, wall-mounted brass faces reminiscent of Medusa. The sleek Carrara marble walls and columns, interrupted by raised, decorative moldings, offer a contrast of surfaces. Docents provide detailed descriptions of each, putting the items in context.

Most captivating are the marble putti — sculpted chubby little boy figures cascading down both balustrades of the grand staircases. These 16 figures represent common professions and pursuits when the building opened in 1897.

Two putti are within arm’s reach: The gardener, equipped with a hoe and rake, and the mechanic, holding a long-necked oil can and cogwheel. Most visitors can easily reach the statues’ toes – and the adjacent sculpted storks – while docents describe their size, posture, attire and expressions, enriching the tactile experience.

— Kathy Tuchman, Robert Horowitz and Karyn Baiorunos are volunteer docents.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 26, 2025

Do You Know What Your Dog is Thinking?

Alexandra Horowitz is the author of “Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know,” which was No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list when it was first published in 2009. An updated version has just been released, and she’ll be at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6 to discuss her work. Horowitz teaches at Barnard College, where she runs the Dog Cognition Lab, and has written other books on her canine research.

This conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Timeless: When meeting a new dog, people will often extend their arm, hand down, to the dog’s nose, instead of reaching out to pet them immediately. Is this actually reassuring to the dog?

Alexandra Horowitz: Well, I think this is an attempt to understand the dog’s point of view, so I understand where it’s coming from. And insofar as it isn’t leaning over a dog and just assuming that they can pat them on the head, it’s an improvement. But it still doesn’t completely take in the dog’s perspective. If I am encouraging somebody who is afraid of dogs on how to greet a new one, I say let the dog decide if they want to come to you. If they want to be petted and they want to meet you, then if you stand with your side to them and not make any aggressive gesture, they’ll come right up to you.

Alexandra Horowitz. Photo: Vegar Abelsnes.

Alexandra Horowitz. Photo: Vegar Abelsnes.Timeless: What is it, in general, that we don’t understand about dogs’ intelligence and how they view us and the world around them?

Horowitz: I think we miss a lot by making assumptions, say, about a dog sitting on the couch with me and thinking they are having the same experience. I guess I’d focus on smell as the thing that has really surprised me, how much it defines who they are and what their capacities are. In smell, we can see that they can distinguish your smell from somebody else’s. They know you by your smell better than by sight. We know that they can recognize themselves by smell and notice when their smell has changed, a kind of self-awareness. They can smell stress in us, actually, and stress is kind of contagious with them. So, the way smell sort of defines their brain, I think is the most intriguing for me and something that there’s really a lot of room to explore.

Timeless: And oftentimes, what we think of as a bad smell is not necessarily what they think is a bad smell, correct?

Horowitz: Oh, absolutely. A lot of my research, and a big focus of this book and my other works, is what it’s like to be a smelling creature experiencing the world because dogs are so profoundly good at olfaction. And one of the things that comes up immediately is just what you mentioned — that we tend to think of smells as kind of good or bad. I don’t think dogs have that kind of impression at all. I mean, there might be a few things that they think are bad smells, but that would be like me saying, “I think of things I see as good or bad.” No, it’s just information about the world. There’s a plant in front of me, here’s a bunch of peaches, here’s a table, there’s a dog. It’s information. What I see through my eyes and what they smell through their noses is similar information.

Alexandra Horowitz will be discussing “Inside of a Dog” at the National Book Festival.

Alexandra Horowitz will be discussing “Inside of a Dog” at the National Book Festival.Timeless: You do this in detail in the book, but can you give us a short explanation of how their sense of smell works and how it’s so much wildly better than ours?

Horowitz: I describe it as a sensory parallel universe because I think there are all these smells in the room with me or with you right now, but we’re mostly not experiencing them. Dogs are.

There are so many levels at which they are built to smell. Anatomically, they have these long snouts and can sniff much faster than we can — about seven times a second. That allows them to get a lot more information. Then those odors are sent tumbling down their nose and warmed and humidified to the back of the nose, sort of between the eyes, where there are olfactory receptor cells. They have hundreds of millions more of these cells than we do. This information goes to the brain, where they have a much larger olfactory lobe relative to the rest of their brain than we do. That’s all just on the inhale.

When they exhale, they don’t want to stop smelling, just as we don’t want to close our eyes to see one thing and then the next thing, so they exhale out of the slits on both sides of their nose. This allows them to do a kind of circular breathing. This then ties in with their vision.

I worked on a paper with a group at Cornell [University] in which they used a special kind of imaging to look at dogs’ brains and found that there’s a white matter connection, just like big tracks of neurons, connecting the olfactory lobe to the visual cortex, something that is absolutely not happening in the human brain. So, dogs are probably incorporating what they’re seeing and what they’re smelling instantly, versus how we do it.

Timeless: One of the things you write about is how we anthropomorphize our dogs, which can create misunderstandings. One of these is how we think they’re acting guilty about doing something wrong — an accident on the carpet, say — when they’re actually responding more to our tone of voice and manner.

Horowitz: Yeah, exactly. When I started studying dogs, I was surprised that they hadn’t been a research subject, the way that there is a lot of comparative cognition work on primates and dolphins and rats and mice. And I was like, why aren’t dogs being used? It occurred to me that it was because we kind of think we already have a vocabulary for what dogs know and understand, just from living with them.

I decided to explore empirically whether some of the attributions we make to dogs are correct. And one of the early behaviors I chose was that guilty look that you described: Whereupon being caught having done some misdeed, they turn away or make their body really small, or they do a really fast low wag, or their ears are back. We call that the guilty look because they look guilty, they look like they understand “I did something wrong.”

So, I did an experiment and it turned out that dogs show the most guilty looks when the owner thinks they’ve done something wrong, even if they haven’t. So, the dog is clearly responding to the owner’s behavior. If you come in and treat them like they’ve done something wrong, they’ll learn to put on this basically submissive look.

That’s really different than the dog kind of ruminating about that garbage can they got into three hours ago when the owner was away. The owner is angry that the dog did that, but the dog is not sharing that understanding. Instead, they are very responsive to us. They learn that when we come in looking angry or using an angry tone of voice, they get punished. So, they learn the guilty look, but it doesn’t mean that they are feeling guilt at that moment. I think that’s important. It doesn’t mean that they don’t feel guilt — again, we don’t have access to their interior lives — but it just means that sometimes what looks like guilt to us is something else.

Timeless: Last question. From the dog’s point of view, what do they do when they’re feeling really affectionate and happy toward us?

I don’t know if there’s one thing, but it’s more like a constellation of things which we would recognize. Things like staying close to us or licking in the face. That’s usually done as a greeting, but it’s also sort of a kiss. The excitement they have when greeting us when we return home — a strange dog won’t be happy to see you return, but the dog who knows you and who considers themselves part of your family is delighted. And we all know what that greeting looks like: Tails going bananas, jumping up, ears back and whimpering. It’s something like what wolves in a wolf pack do to each other when they return to their natal group. Dogs do that kind of thing with us.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 19, 2025

How Do We Know You’re Not a Communist? The Red Scare that Ripped America Apart

Clay Risen spent six years working on “Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism and the Making of Modern America,” a narrative history of the anti-communist panic that consumed the country in the decade after World War II. Americans, fearing the communist Soviet Union and communism advancing across Asia, grew paranoid. While the threat of Soviet espionage was very real – Soviet spies had infiltrated the Manhattan Project, to build the atomic bomb, for example – but what Joseph McCarthy, a U.S. senator from Wisconsin, did in the 1950s was turn mostly old issues into an ongoing hysteria. Thousands of innocent people lost their jobs, books were banned and charges of communist leanings were taken to extremes. Risen will discuss the book at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6.

This conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Timeless: Part of the impetus for this book actually came from your childhood, when your grandfather, who had worked for the FBI during the Red Scare years, told stories about that work.

Clay Risen: Sure, when I was a kid he’d tell this one story in particular, about a time he was working in Chicago. He got a call from a guy who said, “Hey, you should check out Mr. Gruber, he’s a Nazi.” So he’d go check out Mr. Gruber. And Gruber would say, “A Nazi? That’s ridiculous. I came here as a kid and my son is in the Army, and I have a flag in my store. What you should do is check out Mr. Rosenstein, he’s a communist.” So, my granddad would go see Rosenstein, who would say, “That’s ridiculous. I’m a registered Republican.” Then he interviewed the neighbors, who’d say, “Oh, Gruber and Rosenstein, those guys hate each other. They’ve been at it for years. They’re just trying to get the other one.” It’s a funny story, but what stuck with me was, even before I could articulate it in these terms, was that these guys were using the police power of the state — my grandfather — to go after each other. It was funny at first, but it’s also really scary when you think about it.

Timeless: Everyone remembers Joseph McCarthy, the Wisconsin senator who rose to fame, or infamy, as the most visible red baiter of the era. Who do we not remember who also played a critical role?

The person who really kicked everything off was J. Parnell Thomas, a U.S. representative from New Jersey. In 1947, he was the chairman of the House Un-American Activities Committee and began to go after any and all suspicions of communist connections. His biggest target was Hollywood. This is where the famous Hollywood 10 witnesses came and testified, they were all resistant to the committee and they all went to jail. Even then, it was clear that Thomas was grasping at straws, that he was self-promoting, and so he had picked the biggest target: Hollywood.

Also, when you’re looking at the life story of Richard Nixon, you look at the way that he carried himself and the way that he used HUAC to improve his standing? It was pretty masterful. And I don’t think he was completely wrong. He was the driving force in going after Alger Hiss, and he was right about him. [Hiss was a high-ranking State Department official who was charged in 1950 with spying for the Soviet Union during the 1930s. He was convicted of perjury and went to prison but maintained his innocence.] So Nixon is another figure who really helped elevate the Red Scare. Without him, I don’t think the Red Scare, or the campaign of adamant anti-communism in Congress, would’ve had the widespread purchase and legitimacy that it did had Nixon not been there to give it a little polish.

Author Clay Risen. Photo: Kate Milford.

Author Clay Risen. Photo: Kate Milford.A lot of the communist accusations in the Red Scare of the 1950s really had to do with political groups and actions during the New Deal era of the 1930s, not so much post-World War II espionage, when the Soviet Union was our clear Cold War enemy.

By the 1950s, New Deal progressivism had really lost a lot of its steam. That’s when the backlash set in. In the Red Scare, it was almost like they were pursuing ghosts. The big cases at the time — things like the Alger Hiss case — revolved around things that he was said to have done in the 1930s. No one accused him of being a current spy. Alistair Cooke, the British journalist, wrote a book about the era, “A Generation on Trial: USA v. Alger Hiss,” That that really captured what was going on. So, much of the Red Scare was this kind of delayed reaction from a fight that had had relevance in the 1930s, but almost seemed beside the point in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

A lot of the headlines were about targets in Hollywood, at first screenwriters and then big names on screen.

Yes. And just to underline, these accusations were baseless or based on some set of criteria that really had no place in a democratic society. Things like, “You signed a petition that was circulated by an alleged communist front in 1935.” Or, “You appeared onstage with Paul Robeson, and we all know Paul Robeson [the actor, singer and activist] is a left-wing radical.”

So, there were these self-appointed investigators and lawyers who would go after people who had been smeared or targeted in some way and say, “Come to us with your issue, Hollywood stars, and tell us why you were wrong. Write it all out and if we believe you, we will lobby your case to the executives of Hollywood. But if we don’t believe you, we’re going to tell the executives of Hollywood that you are to be banned forever.”

And they were powerful enough to get scores of letters from names like John Houseman, John Ford and Vincent Price. Lena Horne had a file that was particularly extensive and really kind of mind blowing, but these groups went back and forth between themselves, like, “Is Lena Horne sufficiently sorry for what she did?” It was very much a star chamber.

Was there ever a point at which people said, “OK all that’s over and, wow, that was a terrible thing?”

No, there was never a reckoning. There was never really a moment where the country said, “We need to atone for this.” Or even that everyone recognized that something bad happened. Part of the Red Scare that is different maybe from things like Jim Crow or other periods of injustice in American history is that even to this day, there are a lot of people who think, “Yeah, that was OK,” or “We got a little carried away, but it was justified.” Or they say, “Well, what we did was fine. What McCarthy did was bad.” There’s a lot of that. Harry Truman was, I think maybe an exception. He created an executive order in 1947 that was the first real program for loyalty tests in the federal government. It very quickly got out of hand. Later, he wrote in his memoirs that he essentially said, “I made a huge mistake.”

What was your ultimate takeaway? Is it just a sad chapter in American history or something more ominous?

I think it’s something much more ominous. I think that, look, this is a country founded on the belief that we all have inalienable liberties and that we are all sovereign individuals who delegate certain powers to the government. And so fundamentally, we should hold that as the highest priority. And yet the Red Scare is one example among many, unfortunately, where we very willingly threw that all aside. And it’s not that there wasn’t any justification. The Cold War was real and Soviet espionage was real, but they were used as an excuse to trample on the civil liberties of tens of thousands of Americans. I mean, broadly speaking, millions of people lives were intruded upon by investigators. I don’t think that we really learned our lesson from that.

I think that what the Red Scare indicates is that these things are a recurrent aspect of American political life. The fundamental mechanisms come back time and again, and in a country that depends so much on freedom of speech and the freedom of association — and just the freedom to live your life the way you want — we give that all up so easily. We need to remember that.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 14, 2025

Crazy About Those Martians!

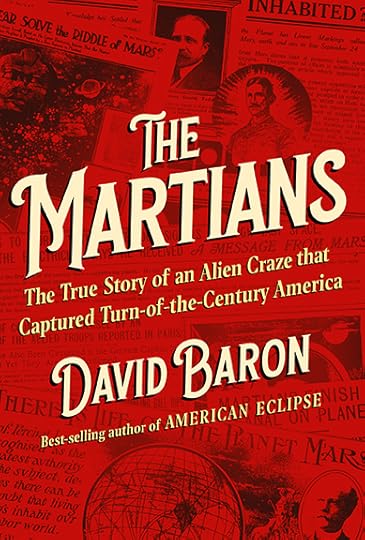

We’re talking today with David Baron, author of “The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America,” who will be at this year’s National Book Festival on Sept. 6. It’s about the public fascination with what looked to be the very real possibility of life of Mars. The main cultural artifact of this belief might be H.G. Wells’ 1898 novel, “The War of the Worlds,” which imagined hostile Martians invading Earth in spectacular fashion. But as Baron writes, most of the views were utopian, picturing Martians as a far advanced, heroic people. He researched part of the book while holding the 2020-2021 Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress Chair in Astrobiology, Exploration, and Scientific Innovation, part of the John W. Kluge Center.

This conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

Timeless: The whole fascination with Mars in this era started in the late 1870s. Tell us about that.

David Baron: Yes. In 1877, a year when Mars came especially close to Earth, an Italian astronomer named Giovanni Schiaparelli in Milan decided he was going to make a new map of Mars. Night after night, he was studying the planet through his telescope. Mars turns on its axis about once every 24 hours like Earth, so he could see features come into and rotate out of view. It looked as if Mars had oceans and continents like the Earth. But Schiaparelli noticed what he thought were really thin straight lines that crisscrossed the planet. He assumed they were waterways, like the English channel. He called them “canali,” which in Italian means channels, but it was mistranslated into English as canals. It stuck.

Timeless: The idea of intelligent life and canals on Mars gained steam and by the 1890s, the hero of the book, Percival Lowell, an extremely wealthy, very prominent Bostonian, goes all in on astronomy and Mars.

Baron: Right, Lowell was well-educated, incredibly smart, articulate, famous. His family founded the mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, and they were very much involved in Harvard. They were instrumental in creating the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. For years, Percival, the wealthy son, was a roving anthropologist in Japan and Korea. He wrote books and gave lectures. But in 1892, there was a sort of Mars boom, when some astronomers thought they saw lights and triangles on Mars. This got a lot of attention in newspapers. It was also the era of the gentleman astronomer, and Lowell, who had become fascinated with this, took it to an entirely new level with his wealth. He created the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, in 1894, specifically to study Mars. He was convinced that there was life on Mars, and he was going to make a name for himself as the man who proved that Martians existed.

“The Martians” author David Baron will be speaking at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6.

“The Martians” author David Baron will be speaking at the National Book Festival on Sept. 6.Timeless: Not everybody agreed with the life on Mars idea, but I was surprised at how many serious people did. Alexander Graham Bell thought there was intelligent life there. And then Nikola Tesla got involved in dramatic fashion.

Baron: Tesla was a genius. Tesla was incredibly well known. Tesla was highly respected. And he, after working for so long on the transmission of electricity with wires, got interested in the idea of electrical transmission without wires — wireless. In other words, radio, which is what Guglielmo Marconi was working on, too. In 1899, Tesla went out to Colorado and created an experimental laboratory. He spent the better part of a year studying electrical transmission through the atmosphere and the earth. Again, this is before radio really existed. And one night he was alone in the laboratory, and he started to hear this kind of triplet of clicks. He would hear, click, click, click … click, click, click, repeating like that. He convinced himself it was the Martians. He waited until New Year’s Eve, at the beginning of 1901, and then he announced what he had heard. That just completely took off in the press. It really propelled the Mars mania to new heights.

Timeless: This finally all peaks around 1907 or so.

Baron: Lowell took photographs of Mars through his telescope. They were tiny, about a quarter of an inch, the size of a shirt button, and they were very grainy. You could see that there were features that would come in and out of view as the planet rotated, but he claimed you could actually see the canals, too. Over time, he got slightly better photographs and he convinced himself, and he convinced the public, that they really did prove that the canals were there. By 1907, what started out as a theory that was embraced by the tabloid press was now being taken very seriously by the conservative press. The New York Times was publishing very serious articles about the Martians. The Wall Street Journal said that the biggest news of 1907 was the proof of intelligent life on Mars.

Timeless: And this really resonated all across the culture.

Baron: Oh, yes. The idea of Martians had started out as a fun thing. There were Martians in vaudeville acts and Martians in Tin Pan Alley songs. But by 1908, the Martians were infiltrating religion. You had pastors sermonizing about the Martians as superior beings and what they might be able to teach us. And there was this wonderful article that ran in a number of newspapers, a list of the questions that people thought Martians might be able to answer. They weren’t practical, they were things like, “What is the meaning of life? How can we prevent human suffering? Where does the soul go when we die?” There was this real longing for the Martians, I think, to be a kind of guardian angel, a stand-in for God when religion has been undermined by so much science. Lowell, with his science, had given people back a new kind of faith in superior beings that might be able to look after us in a lonely universe.

David Baron, author “The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America.” Photo: Dana C. Meyer.

David Baron, author “The Martians: The True Story of an Alien Craze that Captured Turn-of-the-Century America.” Photo: Dana C. Meyer.Timeless: And then … it all went wrong. There weren’t canals, and there weren’t Martians.

Baron: In 1909, Mars again came particularly close to Earth, and astronomers trained their better telescopes on it. There was a one-time believer in canals, a prominent astronomer in France named Eugene-Michel Antoniadi, who, on one particularly perfect night of viewing when the air over Paris was absolutely still, saw Mars with perfect clarity. He saw that what he had thought was a canal was just sort of a knotted shape on the landscape, or maybe just some gentle shading. It wasn’t a straight line. Antoniadi convinced himself that the whole thing had been an illusion, and he took it upon himself to bring Lowell down. Though he lived in France, he was head of the Mars section of the British Astronomical Association. From that platform, he wrote to astronomers all over the world, he wrote for newspapers and wrote for magazines, that the whole thing was an illusion.

Timeless: Things did not go well for our hero.

Baron: Lowell would never hear of it. But by then there were other astronomers who had better photographs. And so by 1910, 1911, the astronomical community had pretty well decided that Lowell was wrong. But Lowell continued to promote the idea. He said he saw more and more canals. He would go out on the road and give speeches portraying himself as this misunderstood genius. I think it’s safe to say that Lowell really was delusional at that point. He died in 1916 of a brain hemorrhage, still convinced that the Martian civilization existed.

Timeless: And so what is his legacy today, do you think?

Baron: He gave the public what they loved, which was the idea of a civilization next door. That excitement was real. It was Lowell’s Martians, which never existed, that really spurred what we know today as modern science fiction. And it was more than that. It helped launch the Space Age itself because the early rocket scientists, including Robert H. Goddard, the father of American rocketry, was very explicit that it was as a boy reading “War of the Worlds” that inspired him to think, “Well, gosh, could we actually find a way to go to Mars?” Wernher von Braun first built rockets for the Nazis, but then came to the U.S. and built rockets for NASA. He grew up reading fiction based on Lowell’s Mars that got him excited about the idea of space travel. So, the early rocket scientists were inspired by him, too.

August 11, 2025

19th-Century Mug Shots: The Face(s) of Counterfeiting

As we mentioned earlier this summer, counterfeiting was a huge problem in the years after the Civil War, when the nation struggled to establish a single paper currency. This led to the creation of the U.S. Secret Service to track down counterfeiters and, in turn, to the agency compiling what we now call mug shots.

The Library acquired more than 1,200 of these from the collection of ace counterfeiting detective Bill Kennoch, and they are a marvelous glimpse at how we lived and looked in days gone by. (These fall into the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse category, as they are copyright free and yours to use in any way you wish.)

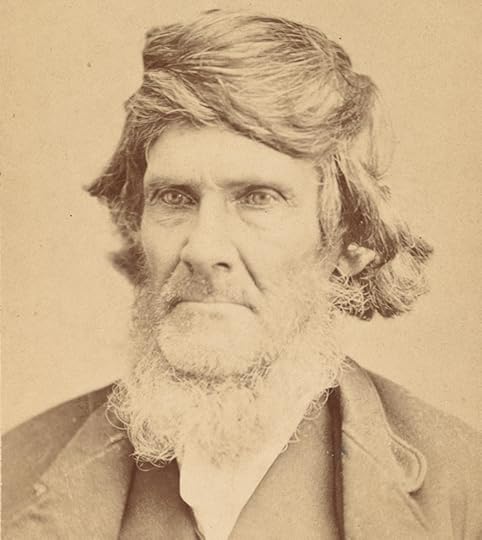

Orvill Ball took this wig (or wild combover?) to extremes in this photograph after his arrest for counterfeiting in Scranton, Pennsylvania, between 1865 and 1886. Photo: Sedgwick S. Hull. Prints and Photographs Division.

Orvill Ball took this wig (or wild combover?) to extremes in this photograph after his arrest for counterfeiting in Scranton, Pennsylvania, between 1865 and 1886. Photo: Sedgwick S. Hull. Prints and Photographs Division.Since counterfeiting was more fraud than violent crime, almost anyone could play a role in it, from making false bills or coins, distributing them in bulk or just passing them off as legit currency in a dry goods store.

This meant, as evidenced by the photographs, that it was open to young and old, rich and poor, men and women, and any and all races and ethnic groups. Most of these were small-time practitioners of the trade, not the type of outlaw that mobilized manhunts and generated headlines.

The aging Orvill Ball did not achieve any worldly renown before or after being picked up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. The back of the card, where agents often scribbled the charges against the accused, only has his name and that of the photographer. Still, for this moment in time, he did cut quite the figure with that head of hair, whether it was all his or not.

Mark Michaelson, the collector and author of “Least Wanted: A Century of American Mugshots,” a 2006 photo book, described these sorts of small timers to the New York Times this way:

“I started to figure out I wasn’t interested in famous criminals or people who’d committed big crimes or very violent crimes. I wanted the small-time people, petty crooks who just fell through the cracks. Instead of being the most wanted, these were the least wanted.”

The Kennoch collection photographs of these least (or somewhat) wanted cover a range about 30 years, from roughly 1860 to 1890, an era when modern criminology was in its infancy. Police around the world had dabbled in using photographs in crime investigations since the 1840s, but it was a French police official, Alphonse Bertillon, who formalized the mug shot in Paris in the early 1880s.

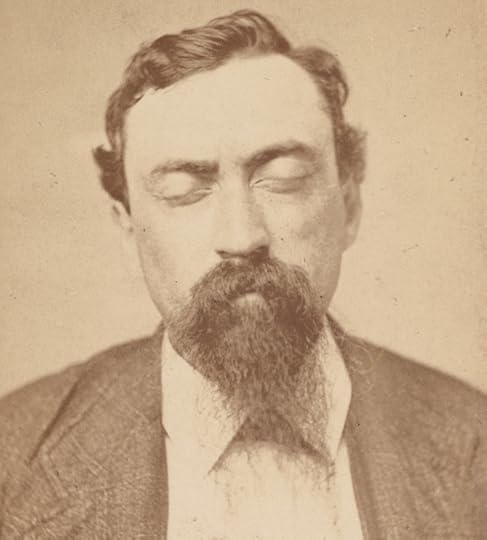

John Duffy was arrested in Philadelphia for counterfeiting in the late 19th century. Like many a portrait subject, he blinked when the shutter snapped. Photo: Charles H. Spieler. Prints and Photographs Division.

John Duffy was arrested in Philadelphia for counterfeiting in the late 19th century. Like many a portrait subject, he blinked when the shutter snapped. Photo: Charles H. Spieler. Prints and Photographs Division.Bertillon used one shot of the suspect facing the camera, the second in profile, and attached these images to a sheet of information about the suspect, most notably several physical measurements that were meant to augment identification. The fingerprint eclipsed most of the other physical measurements a few decades later, leading to the standards still in use today.

The U.S. Secret Service, though, had no standard police cameras. Instead, agents hustled the accused over to the nearest portrait photography studio, where they sat for photos that were usually for cartes de visite, or society calling cards. Such a photograph would have otherwise been a special occasion, if not for the fact that many of the sitters were headed to prison.

So, who among us cannot sympathize with the accused John Duffy? He was arrested in Philadelphia, walked over to have his picture taken … only to blissfully close his eyes, as if he’d just dozed off, when the camera snapped his picture. The man seems peaceful and serene, even while getting booked.

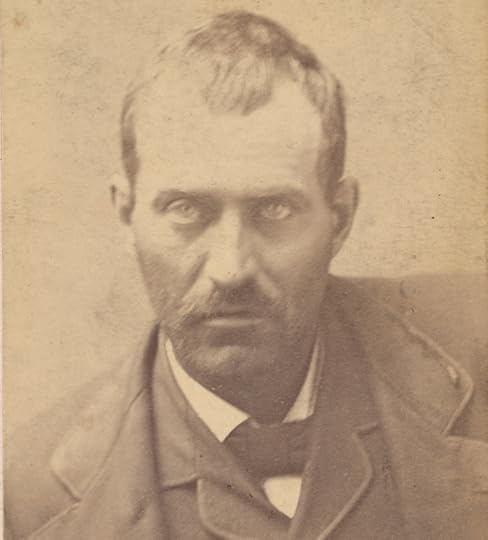

Nickolas E. Cooper of Bay City, Michigan, was booked for counterfeiting coins. Police said he was violent and dangerous. Photo: Miller Bros. Prints and Photographs Division.

Nickolas E. Cooper of Bay City, Michigan, was booked for counterfeiting coins. Police said he was violent and dangerous. Photo: Miller Bros. Prints and Photographs Division.Not everyone seemed harmless. Nickolas E. Cooper was picked up in Michigan for counterfeiting coins. Police started tracking him in Bay City, but only caught up with him in Detroit. Things got ugly. From the brief narrative on the back of the photo: “Went violently insane put into Lunatic Asylum at Pontiac, Michigan. Doctor states that the man is not crazy, only playing it.”

Those eyes, though. They have a glint. It’s the kind of thing you remember, even a century and a half later.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

August 7, 2025

L’Enfant’s D.C. Blueprint Still Shapes Modern Washington

In 1791, President George Washington entrusted French-born American architect and civil engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant with designing a plan for the nation’s capital, giving him a blank canvas to lay the foundation for modern Washington.

A fragile map documenting this plan, drawn by L’Enfant in 1791 and carefully preserved at the Library, is considered a vital piece of American urban history.

Inspired by the cities of Paris and Versailles, L’Enfant added many intricate details to the city’s grid, placing the Capitol at the center, with major avenues radiating outward like spokes on a wheel.

The map reflects his vision of a city of broad avenues, open public squares, low skylines and tree-lined streets named after states, creating a visual reminder of national unity.

L’Enfant included an expansive promenade stretching west from the “Congress house” — today’s Capitol building — toward the Potomac River, labeling it a “Grand Avenue” for both leisure and civic gatherings, a precursor to what became known over time as the National Mall. He placed the White House — labeled “President’s house” — on elevated land northwest of the Capitol, cleverly connecting the executive and legislative branches of government with what’s now Pennsylvania Avenue.

L’Enfant added open squares and circles, such as Dupont Circle, Logan Circle and Judiciary Square, meant to showcase monuments, public buildings and walkable green spaces. Many of them remain today. Other, lesser-known details draw attention to the original working draft. As early as 1796, when Washington transferred the map to commissioners overseeing a survey of the district, he noted that Thomas Jefferson’s penciled instructions to the engraver on the map were difficult to read.

Then there’s the signature: L’Enfant signed his work as Peter Charles L’Enfant, not Pierre, to reflect his adopted American identity after serving in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. His anglicized name also appears in other historical documents, likely a nod to American loyalty and embracing his role in the young nation.

The map changed hands and locations over many years and suffered decades of deterioration due to heavy use and poor storage conditions, as evidenced by its brittle condition, darkened areas and faded ink. After numerous accounts of its poor condition, the map was transferred to the Library in 1918 for safekeeping. It underwent conservation efforts in 1951, and again in 1991, leaning on modern technology to reveal more information.

Frustrated with L’Enfant’s continued delay in submitting a plan to an engraver, an essential step to promote the new location of the nation’s capital, Washington removed him from the project in 1792. L’Enfant died a poor man, never witnessing how the city fully grew into his vision.

His enduring legacy, however, is a blueprint that fused beauty with power for lasting symbolic and historical impact. Even with modern updates over time, traffic circles, public squares and other open gathering spaces are a reminder of L’Enfant’s vision for D.C. as a European-style capital. Just don’t blame him for the rush-hour traffic jams commuters endure.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!July 31, 2025

Preserving the Sounds of World War II

Colin Hochstetler is a graduate student pursuing music at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. He is a junior fellow with the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center’s Recorded Sound Research Center. The interview was conducted by Sahar Kazmi for the Library’s Gazette newsletter.

Tell us a little about your project.

The Office of War Information Collection Lacquer Processing project is one that traces its roots all the way back to the end of the Second World War. OWI was a government organization during the 1940s. They recorded wartime news and American propaganda onto 16-inch discs which were then broadcast domestically and overseas. The Library acquired these discs — tens of thousands of them — around the end of the war and has been working to preserve them ever since. (The complete OWI records are at the National Archives.) My task is to process recordings that came from the OWI’s office in San Francisco. These recordings targeted populations in the Asia-Pacific region and are in languages like Malay, Dutch, Mandarin, Cantonese, Thai, Burmese, Korean, Japanese, Tagalog and Vietnamese.

As I process discs, the metadata I create is uploaded to the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center’s collections management system, making them discoverable to staff and on-site researchers for the first time.

I am currently in the process of compiling everything I have learned from my work and collection-oriented research into a single document so that processing can continue when my fellowship concludes.

Describe a typical day.

My day tends to be a combination of conducting research, completing processing tasks and receiving special training in all things recorded sound with my NAVCC co-fellow and good friend Joseph Sioui. My supervisor, Dave Lewis, believes it is important for us to branch out beyond our particular projects and learn how sound archives function in general, so each day offers something new and special. It could be shadowing a sound engineer, learning how to handle and store historical recording formats, cleaning discs or touring vaults and labs.

Even if I spend most of a day processing, I never know what sort of disc oddities might pop up and complicate my workflow. Processing is never a straightforward task!

What have you discovered of special interest?

I’ve learned that I absolutely love researching institutional history. I was able to sift through OWI acquisition files and discover a plethora of information not only about where these discs came from and how and when they moved, but also gaps in the collection’s history.

Sharing conversations with staff at NAVCC and the Recorded Sound Research Center has taught me a lot about how institutional knowledge can ebb and flow with different people in different times. My process of working with OWI discs has changed as I have learned more about the collection’s history.

What attracted you to the Junior Fellows Program?

The program stood out as a project-based experience that would allow me — encourage me, actually — to combine my interests in research and library work. As a training musicologist, I was particularly drawn to the projects hosted by NAVCC. I am immensely grateful to have the opportunity to work in the largest sound archive in the country.

What has your experience been like so far?

Working for the Library has been one of the best experiences of my early career. I am one of two junior fellows who have the privilege to work on-site at NAVCC. The facility is beautiful, the people are some of the kindest I have ever met and the mentorship is extraordinary. My experience goes beyond this facility, however, as I have been encouraged to travel to Washington, D.C., and explore other areas of the Library when time allows.

A definitive highlight from my various trips to the city has been getting to know staff at the American Folklife Center. I’m an accordionist, and I play lots of polka, so it was a treat to get to know folklife specialist Jennifer Cutting, who also plays. She even let me play one of her button boxes! I also serendipitously had the opportunity to collaborate with reference librarian Andrea Decker, who translated one of the OWI recordings in Malay for my display day presentation. All in all, my experience at the Library has reaffirmed my love for research and archives in ways I never could have anticipated. I have learned so much from so many kind, skilled and enthusiastic individuals.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 73 followers