Davey Davis's Blog

September 8, 2025

The farmhouse, part 4

Image credit: fralo

Image credit: fraloRead part 1 , part 2, and part 3 of The farmhouse. With this final chapter, my ghost (?) story finally comes to an end.

“And give Noah our love,” said Mom. “He’s not still seeing that guy, is he?”

“He dumped him over the summer.” The call was finally winding down and Kendra didn’t want to prolong it with details about Noah’s love life, which was almost as pathetic as hers.

“That’s good,” said Mom. “He needs someone who actually makes money.”

“Mom!” Kendra would have rolled her eyes even if Mom could see her face. She knew Sam was around the corner in the kitchen, her book cracked in half on the table, and she didn’t want her to overhear.

“I’m just being realistic,” said Mom. “The academic life isn’t cheap, believe me.” After an almost imperceptible pause, she said she had to go.

Kendra tapped the red button. For the past hour, Mom had tried to convince her to come home for Christmas, but her begging, threatening, and guilt-tripping (all more or less indistinguishable from each other) hadn’t worked. Kendra could count on hearing about it for a long time, perhaps forever. It would soon be known as the year that Kendra didn’t care about the holidays. But for now, Mom would withhold gossip about their current pet topic—Tim’s wasted MBA—and pretend not to hear her daughter when she said, “I love you.” She sighed and lowered her forehead to her desk.

“You seem close.”

Sam was in the doorway. “I guess so,” said Kendra. She sat up and spun her phone in a circle. “Probably a little too close. I’m the baby.”

“The baby,” said Sam, grinning as Misty nosed between her legs and into the room, tail wagging.

Kendra swiveled her chair. “What about you? Siblings?”

“At one point.” Sam reached down to remove Misty’s collar. To Kendra’s surprise, she went on. “I don’t talk to my family anymore, you know?” With two tobacco-stained fingers, she eased a foxtail from the collar’s fibers.

“I’m sorry,” said Kendra. She never knew what to say to stuff like this, but she decided to take a stab. “At least we have other queers, right?” That seemed correct. Then she remembered that no one had visited Sam since she moved into the farmhouse. As far as she knew, Sam didn’t call anyone on the landline. Even her mail was impersonal: bills, flyers, coupons.

“I lost a lot of friends after my ex left,” Sam said, as if she knew what Kendra was thinking. She stepped down through the doorway, boots tapping the parquet wood. Kendra didn’t like that she wore them inside. Sam reached over her shoulder to set the foxtail on the desk, where it trembled in the path of the heating vent.

“Do you think you’ll ever talk again?”

“To who?” said Sam. She snapped her fingers. The dog yanked her snout from Kendra’s wastebasket and came to her. The collar clicked shut around her neck.

Kendra realized she didn’t know the ex’s name. “Her.”

Sam laughed. “Not my style. When someone loses my trust, they never get it back.” She glanced out the window with purpose, as if expecting to see something other than the orchard vibrating under low and heavy clouds. Then, almost absently: “She was a writer.”

Another personal detail! Kendra was giddy. “I totally get it,” she said. “I’m never dating another artist again. It’s just not worth the drama.”

Caroline had merely been the final straw. Before her, there was the musician who could play every instrument she picked up but couldn’t remember the names of Kendra’s friends unless she was flirting with them, Noah included. Then there was the ceramicist who had cheated on her with her therapist, though to their credit neither had realized it at the time. Others, too.

“So many types of people you’re not allowed to date,” Sam said, pointing to Kendra’s phone. She meant what Mom had said about Noah’s old boyfriend. Jerome, who worked at a call center and had two roommates. “Seems kinda limiting.”

Kendra couldn’t tell if she was being teased. “I just know what I don’t like.”

“Of course you do.” Sam directed a puff of air at the desk, whisking the foxtail away.

Kendra poured them both a double. “Usually my family goes somewhere for Christmas,” she said.

“Me, too,” said Sam. “Last year, we went down to Arizona. Misty loved it. When she rolled in the sand, she looked like a sugar donut.”

Kendra laughed. “I love Christmas traditions. They’re so cozy.” At her elbow, her phone lit up. Another text from Mom. It was a photo of Dad and Tim decorating the tree in “ugly” sweaters from Target. She turned off her notifications.

Sam eyed her phone. “Does your family have any traditions?” she asked.

“Not really,” said Kendra. “You know, other than the regular ones. The tree and presents and stuff.”

“What about ghost stories? Those are pretty traditional.”

“I’ve never heard of that,” said Kendra. “That doesn’t seem very cozy. Making up stories to scare each other.”

“What if they’re not made up?” Sam tipped her head to empty her glass in one big swallow.

Kendra laughed. “You believe in ghosts?”

Sam wiped her mouth with her sleeve. “You don’t?”

“Well,” said Kendra. Of course she didn’t.

“Not, like, white-sheet ghosts that go boo! I think a ghost is more of a feeling. What happens when you notice a place is missing something. But in being noticed, the missing thing becomes a presence. You know?”

Butches could be so corny. “I hadn’t thought about it like that,” Kendra said. She imagined the face Noah would make if he were here.

Grinning, Sam tapped her pockets for a lighter. “Be right back,” she said, heading for the porch.

Kendra opened her phone. Silenced Cyte notifications wiggled for her attention, but she opened her Contacts instead. She felt the urge to call someone, though she didn’t know who. Not Mom. Not Noah. She scrolled, waiting for a name to capture her attention. The letters swam on the screen, then went dark.

Sam was behind her, covering her eyes. Now that she was close, the flower hidden inside her leather and tobacco scent revealed itself with a flourish: geranium. Their laughter filled the kitchen. When Sam pulled her hands away, Kendra saw that Misty was circling the dining table, panting, her ears back against her head.

When Kendra got back from the airport, the river fog was still thick on the interstate. “No rain forecast for tonight,” said the man on the radio, “but Santa’s really going to need Rudolph’s help to make it through this cloud cover.”

Though the farmhouse was still dark, Kendra knew Sam was awake. She had heard her throwing up in the bathroom while she was in the kitchen, pouring whiskey in her coffee—just a little, enough to drive Noah to the airport. Clutching the gift-wrapped box Noah had given her, she tiptoed to her room and got back into bed, praying she wouldn’t need to get up again for a few more hours.

Your Life, Your Content. Though she and Noah had stopped at a gas station, a Starbucks, and of course the airport, one of the most surveilled locations in the tristate area, nothing much was happening on Cyte yet. Despite having promised herself she wouldn’t look at any new videos of Sam, she was disappointed not to find any in her feed.

“So then she told me that I thought I was too good for her,” said Kendra. Instead of waiting for Sam’s invitation, she had gotten started on their nightcap without her. By the time Sam joined her at the kitchen table, she already had the pleasantly dizzy feeling that comes from drinking on an empty stomach.

“Oh, yeah?” said Sam.

Was she being sarcastic? Sam seemed tired this evening, almost on edge. But with the help of another drink, Kendra rejected the embarrassment encroaching on her buzz. If she could listen to Sam talk about her shitty ex, the woman who had broken her heart and run out on her, she could do the same for Kendra. “Yes!” she cried. “She really did. But then—you’re not going to believe this—she said that I was right. That I was too good for her.”

Sam had taken off her sweatshirt. Underneath was the masculine version of the white tank top that Kendra was wearing. “Well,” she said, “did you think you were too good for her?”

Why was Sam being so hostile? Why was it making Kendra blush? “I mean, like, yeah I grew up in a nice house with nice parents,” she admitted. “No one hit me. I don’t have a sad coming out story. What am I supposed to do? Pretend I’m not who I am?”

Sam frowned.

“What?” demanded Kendra. She felt weightless, as if the only thing keeping her from floating away was the pressure of Sam’s boot against the leg of her chair. “Just because my life is easier my ex can do whatever she wants?”

“You didn’t answer my question.”

Kendra’s head started to hurt. How could Sam be taking Caroline’s side? She had to make her understand. “Look,” Kendra said, pulling out her phone. “Just look and see who’s better than who.”

She opened Cyte, rapidly navigating through the user interface. She had only watched the video once, but she remembered the thumbnail vividly: the front door of their old apartment, the first few steps of the stairway, Caroline’s arm around the chubby girl with the bangs. When she found it, she looked up to confirm that Sam was watching before she pressed play.

The thumbnail came to life. The chubby girl was trying to go up the stairs, toward the camera, but Caroline had taken her hand, pinned her to the wall, kissed her in the pink light of the pull-chain lamp.

The phone shook in Kendra’s hand. Caroline had known about the camera. She had installed it herself when the old one broke. Nothing about this video—the night out when Kendra was on a trip with her family, the chubby girl, the kiss—had been a mistake or lapse of judgment. She had done it on purpose. Even now, months later, watching it returned Kendra to the deepest fury of her life.

Suddenly the app refreshed. The next video to load was another one Kendra had seen before. She locked the screen as fast as she could, but it was too late. Sam had already recognized the farmhouse kitchen, her own body, the orchard in the dark window.

“What the fuck,” said Sam.

“I’m sorry,” said Kendra. Her head was pounding now.

“What the fuck!”

“Wait—”

Sam got to her feet, shaking Kendra’s hand off her arm. At her bedroom door, she turned, as if to say something else. But she was just waiting for Misty to come inside before closing and locking the door behind her.

When Kendra woke up, she was in her bed. It was dark, but she could see the orchard waving silently in the windows. She didn’t remember how she’d gotten there, or when.

She looked down the length of her body, past the foot of her bed and her desk chair, to the bedroom door. It was open. Inside the black rectangle, someone was standing. They were looking at her.

Kendra could hear her eyes blink. When she opened her lips, they cracked like cellophane. Her mouth was dry and sour. She remembered the gin in her night stand. She tried to say something, but nothing came out.

And so, for a long time, she didn’t move. They didn’t, either.

When Kendra woke up on Christmas morning, the sun was warming her windows. They held the orchard, now motionless, as if it were a portrait hanging on her wall. The door was closed. She got out of bed and went to her bathroom, making it to the toilet just in time.

When she was finished, she checked the drawer of her night stand. There was no gin bottle; she ran out last week, she remembered. She went to the kitchen. The glasses and a half-empty pack of cigarettes were on the table. Next to them, the whiskey bottle was almost a quarter full. Sam’s bedroom door was still closed.

The bottle under her arm, Kendra tiptoed back to her bed and opened her phone. Already there were Christmas texts. Miss ya, bean, from Dad. merry christmas to you and mr. girlfriend! from Noah. Nothing from Mom.

Head still pounding, Kendra put down her phone and picked up a book. She stared down at the meaningless words, suppressing her nausea with slow, deep breaths and small sips of whiskey.

The patch of sunlight was dappling her blankets when she finally gave in. This late in the morning, there were dozens of videos in her Cyte feed. Her eyes watering, she watched all of them at least twice, poring over every face whether she recognized it or not. But there was nothing new from last night, from any of the farmhouse cameras.

Cranking the wheel, Noah pulled out onto the highway. “Bye-bye, Mr. Girlfriend,” he said to the rearview.

Kendra rubbed her thumb over her phone’s flat, black face. It was dead. Behind her, the back seat was crammed with boxes and shopping bags. This would be their only trip. It was easier to leave most of her furniture behind at the farmhouse. She’d get more when she found her own place.

It didn’t take them long to get everything inside, though both of them moved slowly, trapped in their respective hangovers. When they were finished, Noah joined Kendra on the couch with his weed tray. He liked having her at his place, but he didn’t understand why she’d left the farmhouse. “Because she looked at you?” he asked again, tapping the grinder on the coffee table. Kendra hadn’t seen the point in telling him about the cameras.

They spent the afternoon watching reality TV and eating unseasoned popcorn. For dinner, they opened a bottle of wine. After his second glass, Noah went to bed.

Kendra plugged in her charger next to the couch and wrapped herself in Noah’s spare comforter. She held her phone in her hands, waiting. It took a long time for it to warm, but she wasn’t impatient. She wished it would take longer, in fact. She wanted to put her phone down and fall asleep and never wake up, but she couldn’t tear her eyes away from the screen.

Finally, the apple glowed. It took her three tries to enter her passcode correctly. When the home screen finally loaded, she thought, for a terrifying moment, that her Cyte app was gone. No, it was right there—the icon’s color had changed slightly because of an update. The tagline, however, was the same as it had always been: Your Life, Your Content.

There it was, her room at the farmhouse. Judging by the sunlight in the window, the video must have been taken within an hour of her leaving. When she tapped the thumbnail, it didn’t play. She was about to tap it again when someone suddenly entered from the kitchen. It was Sam, a stepladder under her arm. Kendra pressed her body into the couch, retracting her face a few more inches from the screen.

But she watched. Her boots heavy on the parquet wood, Sam was strolling across her bedroom floor. When she left the camera’s range, Kendra could still hear everything: her feet tapping, the stepladder clicking. Then, silence. Her thumb hovered. Was the video over?

Fast as a glitch, Sam’s body vaulted back into the frame. She had climbed the stepladder to face the camera, her face filling the screen—high forehead, heavy jaw, squinting eyes. Looking Kendra dead in the eyes, she smiled.

Thank you for joining me as I try a little something different. If you’d like to support my work—most of which is free—you can subscribe, buy my books, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

September 1, 2025

The farmhouse, part 3

Image credit: fralo

Image credit: fraloRead part 1 and part 2 of The farmhouse. My ghost (?) story continues as Kendra starts getting to know her strange new roommate.

As simple as Kendra’s life was at the farmhouse, there was something indulgent about it, too. The meager meals, cheap liquor, and AI-scripted sitcoms would have been impossible at her old apartment. Caroline would never have allowed such wallowing.

Not that Kendra had much time for TV with second-year exams little more than a semester away. But now that her life had been stripped down to its most basic components, committing herself to school was almost easy. Without Caroline and the queers that came with her—three or four lesbian-spectrum homosexuals with complicated haircuts who had always been a little cold to Kendra, or so she imagined—there was almost nothing else to think about.

Mom called twice a week, always with news to share about her job and Dad’s job and what Tim, who was underemployed and living in a duplex six blocks away from their childhood home, was up to. When the calls ran long, as they usually did, Kendra put her phone on speaker so she could look at Cyte as she listened, a habit Caroline used to tease her about. If one of them was out of town, she would sometimes text Kendra, should I call so you can look at cyte?

and? It was a brisk spring day the first time Kendra felt the joke’s hard edge.

jesus, texted Caroline. relax.

After that, Caroline had stopped joking about Cyte, though Kendra was using the app more frequently, even when they were together. When she ran out of new content, she trawled her Explore tab, organized by the videos’ locations, subjects, and incidental sponcon (Subway billboards in the background, Hershey’s wrappers in the wastebasket) in search of flattering memories of herself and attractive strangers all over the world. In the weeks preceding their breakup, these videos replaced Caroline’s face as the last thing Kendra saw before she fell asleep. When her feed showed her a video with Caroline in it, Kendra found herself swiping past almost immediately, rather than lingering as she once had. Caroline didn’t like Cyte anyway.

“Doesn’t it bother you that nothing is private anymore?” said Caroline. “They can see everything we’re up to.” The way she said they made the entity seem much grander, and far more interested in what Kendra was doing, than the NSA, or whoever, could possibly be.

“They’re already watching,” reasoned Kendra. “I might as well, too.”

Caroline scoffed and went back to her book.

In hindsight, Kendra couldn’t believe that she’d gotten this far into her program with a partner holding her back. Romantic relationships weren’t just intimacy and companionship, sex and squabbling. They were a drain, a net loss, because of all the ways that caring for someone else required time, energy, and a sense of obligation. The three main ingredients of work, in other words, and Kendra had enough of that on her plate. If she went for her PhD, she’d only have more of that to worry about.

Because even when she and Caroline were happy—and there had been good times, Kendra had to admit—their problems never seemed to resolve. Like the paintings. Or how Caroline thought Kendra spent too much money on brand-name groceries, but refused to allow Kendra to just pay more than her share. Or how Caroline insisted on driving to the next town over every other weekend to visit her mom at her grim little apartment, where the piebald carpet smelled like gasoline. Caroline’s mom spent the majority of her waking hours in her La-Z-Boy drinking boxed wine, which her daughter would inevitably mention in the fight that concluded each visit. For Kendra, watching her girlfriend bicker about her mom’s unpaid bills or diabetes medication was like watching her push a mop in a pair of muddy shoes. She and Caroline always had an argument of their own after they left, sometimes while they were still in the car.

Being alone, Kendra now realized, was just easier. Not that she was lonely out here in the boonies. She met up with Noah in town once or twice a week, and she saw her professors and other students when she was on campus. And when she was at the farmhouse, which was most of the time, Sam was usually around.

I wish you hadn’t moved, texted Noah.

omg im literally 25 mins away

don’t you get bored? it’s just you and Mr. Girlfriend out there. This was Noah’s nickname for Sam.

lol at least i have a Mr. in my life

rude. Noah’s reply was closely tailed by a snap of his manicured middle finger.

The second time Sam appeared in her Cyte feed, Kendra would recall, with a stab of guilt, that she really had meant to tell her about the cameras. From her bed, she watched her roommate read on the front porch, the smoke from her cigarette conjoining with her breath in the same sparkling cloud, Misty’s tail occasionally fringing the lower edge of the screen. When was this one from? Last night? Last week? Cyte videos weren’t always timestamped.

But by then Sam was already at work, and since she didn’t have a phone, Kendra couldn’t forward her a link. She forgot about the cameras until the next video of Sam arrived: wearing only sweatpants, her roommate walking into the kitchen and staring out the black window, as if there was something in the orchard waiting to be seen. And again: Sam sitting on the couch in the living room, using a Leatherman to peel a honeycrisp before eating it in small, precise bites. Misty got the core.

Then there was the video that confirmed there was a camera in Kendra’s own bedroom: her ankles grimly jerking under the comforter as she masturbated. She found it above the door frame. Unlike the other cameras, it was almost impossible to see if you didn’t know it was there.

Kendra could have removed it, or covered it, or even broken it, but she didn’t. Every time a new farmhouse video came through her Cyte feed, it was either too early in the morning or too late in the evening, her bed too toasty, her head too fragile, to get up and give Sam the news.

After a week or two, Kendra felt she had missed her chance to say anything about the cameras. And anyway, it wasn’t that big of a deal. It wasn’t like she was spying. And she was the only person out here—other than Noah, when he occasionally visited—who might see them.

From now on, she promised herself, she wouldn’t look at any new videos with Sam in them if they appeared in her feed. After that, she felt a lot better about the whole thing.

On a Saturday evening a few weeks after she moved in, Kendra went to the kitchen to make some of the skinny tea she stole from Noah. Sam was reading at the dining table, a glass of whiskey by her wrist. They struck up a conversation about her book, a true crime tome called Devil in a Red Dress.

An hour later, they were still talking. When Kendra finished her first glass of whiskey, Sam topped it off. When the bottle was empty, Sam went to the cabinet above the fridge, just a few inches away from the camera, for another.

Kendra liked drinking. She liked hangovers, which made it easier to not eat in the morning. And she liked talking to Sam because she didn’t gossip, which meant that they couldn’t discuss the other queers in town. Rubbing the back of her sunbaked neck, Sam held her own on a wide variety of subjects, informed by voracious reading from sections of the local used bookstore more or less foreign to Kendra: sci-fi, American history, self-help.

“Did you get your masters here?” Kendra asked.

Sam grinned. “I’d have to go to college first.”

“Oh,” said Kendra. She looked down into her glass, the twin of Sam’s. Almost everyone she knew had a degree, or was in the process of earning one. To conceal her embarrassment, she adopted a teasing tone. “Well, why don’t you?”

Sam laughed and changed the subject, which Kendra was learning was typical of her. Though their nightcaps became regular events as the weather got colder, their conversations ranging far and wide, Sam avoided talking about herself. No matter how subtle Kendra’s questions, any attempt to learn more was delicately circumvented by the introduction of Bleeding Kansas, or the Sultanate of Women, or the Copenhagen interpretation, and Kendra would follow along with a reluctance that was soon forgotten.

“You’re pretty private, aren’t you?” Kendra said. It was the Sunday before Thanksgiving. After dinner, she had changed out of her habitual sweatpants into a clean pair of tight jeans. Draining her glass, she crossed her legs under the table. Maybe she’d have Noah braid her hair the next time he came over.

“I’m an open book,” said Sam. “Just not a very interesting one.” She got to her feet and picked her coat up off the back of her chair. “Gonna smoke.”

Later, as Kendra was scrolling Cyte in bed, a new video appeared: Sam smoking on the front porch, her book on her lap, her eyes on the trees. Kendra watched for a few seconds before she remembered. With a reluctant flick of her finger, she sent the video away. When the next one began—it was Noah scrutinizing his hairline in the CVS self-checkout, a bottle of Gatorade Zero in his hand—she watched it three times in a row without seeing a thing.

That Wednesday night, the bar & grill was empty except for Kendra and Noah. They chatted with the bartender, a middle-aged man who topped them off for free and let them choose the music he played over the speakers. When Noah began interrogating him about his rising sign, Kendra decided it was time to go.

Noah smoked a joint in the passenger seat, the moon leering over his shoulder. Kendra, who had long believed that a couple of drinks actually made her a better driver, inched into the clearing like a teenager sneaking in after curfew. The windows were lit, but the green truck wasn’t under the carport. “I wonder where Sam is,” she said, yanking the parking brake.

Noah rubbed his eyes. “Mr. Girlfriend didn’t leave town for Thanksgiving?”

“No,” said Kendra. “She never goes anywhere.”

“So what does she do all day?”

“I mean, she goes to work, but that’s it. Otherwise she hangs out around here. Or out in the orchard.”

Noah laughed. “What’s she do out there?”

“I don’t know,” said Kendra. She didn’t know why she’d never asked.

In the kitchen, she sat down at the dining table and opened Cyte.

“Did I tell you I deleted mine?” asked Noah. He was rifling through the pantry. “No more apps that make me feel bad about myself. I’m doing this negativity fast.”

“Check the the freezer,” said Kendra.

The frozen French bread pizza could be ready in twenty-four minutes. “How does Sam eat this stuff?” Noah said, examining the label.

“We’ll be doing her a favor.”

“And we’ll walk it off while it bakes,” said Noah. He set a timer on his phone.

Kendra sighed, but she followed him back to the living room. “Wish I’d gone home,” she said, putting on her coat again.

“Girl, you’d be walking there, too.”

In fact, Mom and Dad and Tim were probably already asleep. They had to be up early for the Turkey Trot. “I can’t believe you stayed, either,” she groused.

“Don’t rub it in.” Noah’s mom and sisters were in Maui as usual, getting tan and downing chichis crowned with pineapple, but this year his dad was joining them. In light of this unprecedented move, Noah, like Kendra, had pretended to have too much grading to leave town.

It was just above freezing outside. They walked quickly over the gravel, but slowed when they reached the field, where it grew more difficult to navigate as they got further from the light. When Kendra tripped over a stump, Noah clotheslined her like a soccer mom at an unexpected stop sign—he had surprisingly good reflexes for a pothead. She only just caught her balance in time. Giggling, they continued on.

But at the edge of the orchard, Kendra slowed to a stop. “Sam said not to go in there,” she said. The trees looked twice as tall as they did from the farmhouse. The branches clawed for each other, though she could barely hear the wind that was moving them.

“We won’t go far,” said Noah. He tugged his beanie down over his forehead. “Do you think it’ll snow this year?”

“I think those days are over,” Kendra said, which made her feel like Dad. For some reason, she thought of Sam as an old woman, still alone here at the farmhouse. White-haired and frail, her big, firm arms gone slack.

“Just a little further,” said Noah. Using his flashlight app to guide him, he went on ahead. Kendra followed, attempting to place her feet exactly where his had been.

Moving slowly, they passed the first line of trees, then the second, then the third. Every few steps, Noah’s flashlight revealed a new row of trees, each echoing the one before and behind it. Holding his phone in front of him like a compass, he veered north, or what Kendra thought was north. Instead of of veering with him, she kept going straight, treading lightly so he wouldn’t hear her split off. She wanted to see how far she could get before she looked behind her. Lot’s wife. Oedipus. Kendra.

As Noah’s footsteps faded away to her left, the wind rose to replace them. Kendra passed one row of trees, then another, then another. She looked for the moon, but could only see gnarled branches and glistening shadows. Not too far away, she reminded herself, the highway led back to town, where there were people and houses and electric lights. Swinging her arms and puffing out her chest, she summoned her courage with big, purposeful steps—it was an almond orchard, not Hansel and Gretel’s haunted forest. As if overtaken by a burst of carefree energy, she jumped for a branch as she passed beneath it, but landed wrong, twisting her ankle. When she knelt to feel it, she heard something behind her move.

Kendra stood very slowly and turned very quickly, but all she could see were trees and the farmhouse, which was farther away than she thought it would be. The few visible windows were small and yellow, like kernels of corn. On this side of their light, the pale tree trunks were black. She got the feeling that, if she reached out to touch one, her hand would keep going forever, her body following it into the darkness. She was very cold. Where was Noah?

Another sound—this one low but powerful—broke the silence. Kendra couldn’t place it until it came again, then again. She had never heard Misty bark before, she realized. It was strange that a girl dog could sound so unfemale. She was getting closer, from which direction Kendra wasn’t sure. She spun around again to find herself lost inside a bright white light.

“Easy!” said Sam, and the dimmed enough for Kendra to see Misty at her feet. The dog lunged, her collar cutting into Sam’s fingers, but her barks faded into one long, ragged growl.

“Fuck,” whispered Kendra. The dog steamed in the cold, straining against Sam’s grip.

“You scared us,” said Sam. “Couldn’t tell it was you at first.”

“Hey!” Noah was almost running toward them through the trees, his phone bright in his hand. “What are you doing out here?”

Sam palmed the heavy part of the flashlight like a cop, its beam bouncing up and down the length of Noah’s body, as if she didn’t recognize him, either. She tilted her head at the farmhouse. “Something was burning.” Now she released Misty’s collar. Her eyes glowed, but the dog seemed to have relaxed. Her tongue hung from her jaws like a slice of meat.

Blowing into their palms, Kendra and Noah obediently followed Sam back home. Misty kept pace with them until an owl’s screech—the first birdsong Kendra could remember hearing that night—drew her back into the trees.

Noah shoved his hands in his pockets and skipped ahead. “I’m fucking freezing!” he said over his shoulder. “And starving! Do you think we can get delivery out here?”

Sam trotted after him, her keyring singing on her hip. Kendra was the last to cross over from the orchard to the field. Alone again, she was thinking, when she felt Misty’s breath warm the sliver of skin above her right sock.

Thank you for joining me as I try a little something different. If you’d like to support my work—most of which is free—you can subscribe, buy my books, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

August 29, 2025

Schrödinger's metamour

Spoilers ahead.

About midway through Michael Angelo Covino’s Splitsville, there’s a short scene where Jason Segal-esque schlub Carey (Kyle Marvin), a gym teacher, is directing school drop-off traffic while wearing a bizarre white sweater. It’s knit but not cable knit, which would have been out of place climate-wise but still within reason for the character1. This sweater, though, is made with fluffier, shinier yarn and a looser weave. Compared with Carey’s other clothes, it looks a little young, a little Bushwick-y, a little, well, queer, especially on someone like him. If Splitsville hadn’t already made it abundantly clear that he is a married middle-class straight man in his mid-to-late thirties, you might wonder if something else was going on.

I think of this scene as an encapsulation of Splitsville’s whole thing, which is about what happens when a group of straight marrieds pre-empts what was once known as a midlife crisis by experimenting with an arrangement that reads a little, well, queer—with similarly unflattering results23. After Carey’s wife, Ashley (Adria Arjona) reveals she’s been unfaithful and asks for a divorce, Carey leans on his slumlord bestie, Paul (Covino) and his stained-glass wife, Julie (Dakota Johnson), for support—only to discover that their seemingly idyllic marriage is maintained with a DADT-ish policy of sexual permissiveness. They’re not polyamorous, mind you, just unboundaried; unlike Carey and Ashley, Paul and Julie have decided to sacrifice their own desires for exclusivity in exchange for a relationship in which infidelity isn’t a painful, expensive dealbreaker, just a reason to mistrust and resent your spouse.

Of course, Carey and Julie almost immediately have sex, catalyzing the disintegration of Paul and Julie’s marriage. In the wife-swapping wreckage, Splitsville careens between black comedy, absurdist slapstick (complete with puns and sight gags), and good old-fashioned romcom, all to entertaining and visually impressive effect. Covino calls his sophomore feature an “unromantic comedy,” but between the title cards with legal lingo and the eleventh-hour restoration of both marriages, it reminded me of Production Code screwballs like The Awful Truth (1937), in which jaded rich couple Irene Dunne and Cary Grant get THIS close to finalizing their divorce before rekindling their lost passion thanks to the jealous possessiveness that (naturally!) characterizes true romantic love. Similar to Truth’s Lucy and Jerry, Julie and Paul come to find out that they were secretly paranoid about their partner fucking other people for no reason; only Julie ever redeems her hall pass, with Carey, in desire born of frustration, while the extramarital sex in Carey and Ashley’s relationship is always adulterous, or essentially so—in a world-class move of nice-guy passive aggression, Carey agrees to wear the horns in exchange for continuing to live with Ashley in her veritable bawdy house of lovers (the montage concerning which is my favorite sequence in the film). With its unfortunately heavy-handed ending, when Julie and Paul’s tween son nauseatingly observes, “Sometimes you have to break something to find out how valuable it is,” Splitsville doesn’t need to restore marriage/monogamy4 because it was never lost in the first place.

The job of a romantic comedy like Splitsville, however unconventional it may profess to be, is to take the pulse of straight sexual anxieties. In 2025, our collective heart rate quickens (in fear or hope?) for the specter of nonmonogamy. The threat isn’t merely infidelity, but non-normative (that is, le$$ bankable) relationship configurations. Honoring the genre, Covino resolves these anxieties with a happy ending: in a normal marriage, we’re shown, the desire for sexual intimacy with other people is merely a symptom of arrested development, poor communication, or something else. All’s well that ends well when a successful heterosexual relationship is a beautiful woman’s war of emotional attrition with a man who is either an awkward doormat or an alpha with a personality disorder5. Splitsville would like to believe that its preoccupation with marriage is more concerned with the emotional than the rational (that is, with attraction and compatibility rather than money and property; that is, that resolving the dysfunction of one will do the same for the other). Unsurprisingly, this cynicism renders it almost sexless, when a little more sex would have done it good, in my humble opinion. What sex there is is played for laughs (Carey’s penis, an uncannily smooth prosthesis, is a punchline multiple times), while the rest is implied or teased. This casts in relief repression’s inevitable homoerotics—Carey and Paul’s showstopper of a brawl, which The New Yorker called “a dad-bod ‘John Wick’”; Ashley’s collection of live-in cuckolds, dependable NPCs that Carey can use to manipulate his estranged wife—although the closing scene, which show Julie and Ashley making eyes at each other, belongs to the girls6.

This review is no pan, believe me. Splitsville is consistently funny, pretty to look at, and cast with distractingly beautiful women (both of whom are, incidentally, shortchanged by lack of character development. Adria, you deserve more!). It’s a fun night at a movies, you know? But if Covino wanted to satirize or deconstruct or challenge our conceptions of “modern romance,” he’s done little to distinguish Splitsville from similar forays that are by now almost a century old.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

1Does anyone else feel like they can’t tell what the weather is like in movies these days?

2Yes, I know straight people do polyamory. I watch Couples Therapy!

3I say straight with intention, although I should note that Carey’s wife, Ashley, is bisexual, briefly dating a woman. You know, because woke.

4For these people, there is no difference.

5I’m talking about Covino, who is hot, although the Italian friend I saw Splitsville with contends that, “He’s just Italian.”

6It goes without saying, I suppose, that the wives fucking would no more disrupt the straight monogamous order than Paul and Julie’s unrealized open marriage.

August 25, 2025

The farmhouse, part 2

Image credit: fralo

Image credit: fraloRead part 1 of The farmhouse. My ghost (?) story continues as Kendra learns more about the cameras installed inside her new home.

Though each trip between Noah’s apartment and the farmhouse took nearly a half hour, they finished moving Kendra’s things by lunchtime. After they dropped off the Uhaul, they went to a grimy bar & grill a few exits east of the farmhouse to celebrate with skinny margaritas and a large order of steak fries.

“This doesn’t count because we carried all those boxes,” said Noah, squeezing a thick ribbon of ketchup onto the parchment paper lining the tray.

Their faces hot with pettiness, they swapped tired jokes at Caroline’s expense and rated the dicks in Noah’s Grindr DMs. Kendra was jubilant. For the first time in almost a month, thinking about her ex didn’t make her feel like a loser. The move from Noah’s couch to the farmhouse felt almost like a developmental milestone, as if she was more of an adult now than when she woke up this morning.

Kendra couldn’t see where to put her sticky new key. Behind her, Noah trundled down the farmhouse driveway, his taillights throwing grey arabesques on the gravel. As she fumbled with the lock, her head started to pound.

The lights were off inside, too. The farmhouse, so friendly when Sam was giving her the tour, had become creepy, the living room and kitchen stretching a long, cold mile between the front door and her new bedroom. At her old apartment, the alcove at the top of the stairs always glowed pink from a pull-chain lamp salvaged from Caroline’s childhood. Lately, Kendra had been scrolling through the archived Cyte footage from the camera installed next to it, revisiting three years of rose-colored homecomings: she and Caroline giggling, their arms laden with plastic grocery bags; or butchering, in sloppy unison, a pop song they heard at the townie bar’s weekly queer night; or racing to see who could strip her wet running clothes faster, the loser tasked with drawing their post-workout bubble bath.

A shower by herself would have to do. Kendra turned on the water as hot as it would go and climbed over the side of the tub. Squeezing her eyes shut, she squatted over the drain, praying the spins would go away soon.

By the time the water ran lukewarm, she felt more steady, but the pain in her head was worse. She dug her thumb into her eye socket, as if that might free whatever was trapped beneath her skull—a leaden bee, a nuclear pinball. Sighing, she climbed back out again and wrapped her towel around her shoulders, like she did when she was a child.

The wind had picked up. Unlike the trees in the orchard, whipping each other in its wake, the farmhouse resisted, cracking like enormous knuckles. Oddly still in contrast, the light from her puny desk lamp shadowed dozens of heavy cardboard boxes. Kendra was shivering, but at the thought of searching for her bathrobe, tears stung her eyelids. She wished she was curled up on Noah’s couch in front of a cozy screen, or in the bed that was always made up for her at her parents’ house. Even the old apartment, with Caroline stewing an arm’s length away, would have been better than this.

Sam must have aspirin somewhere, she thought, pinching the bridge of her nose. The green truck had been gone while she and Noah were dropping off the last of her things, but it was back under the carport when they returned from the bar & grill. Kendra peered into the kitchen. There was light beneath the other bedroom door.

She and Caroline had their first big fight the day they moved in together, while they were still unpacking. Kendra had been on her best behavior back then—though they’d been dating for almost a year, it was her first time living with a girlfriend. But their eventual compromise, wrung from the argument like dishwater from a rag, had been so exhausting to attain that they fell asleep on the bedspread, still in their clothes.

It was all because of Caroline’s paintings. Caroline had wanted to hang several in their new place, and insisted on keeping her works in progress in the living room, like half-eaten cakes left to gather flies. (“It’s too bad she can’t sell more of them,” Mom had stage-whispered, eyeing the bright colors and revolutionary slogans at Caroline’s student show.) Kendra could hardly admit to disliking the ones that her girlfriend wanted to display, but she could reasonably object to the living room being used as her studio. After two hours of heated debate, it was agreed that Caroline could keep out one unfinished painting at a time. Though both claimed to be happy with the decision, their home decor was cursed from then on. Kendra hated Caroline’s Craigslisted pottery, and Caroline found ways—more and more blunt, as time passed—to express her distaste for the epigram prints that Kendra ordered from Amazon; she called them “basic,” which was awfully rich, Kendra thought, coming from someone whose best bet for postgrad work was teaching fingerpainting at the local charter school.

Kendra took a deep breath. Sam was her roommate, not her ex. Still, maybe she should text first—but then she remembered that she didn’t have her number yet. Two excuses tipped the scales of propriety. Instead of disturbing Sam, she would just take a peek in the medicine cabinet in her bathroom, which was just off the kitchen. She pulled the towel from her shoulders, rewrapping it around her torso and tucking in the top against her breasts. She would worry about her bathrobe in the morning.

Kendra stepped up onto the cold kitchen tile. Behind her, the desk lamp spread its apron of yellow light a few inches past her foot. Between that and the light from Sam’s bedroom, there was only darkness and the wind in the eaves. Putting her hand out in front of her, she took another step. Fingers slowly wiggling, she placed one foot before the other in small, uncertain steps. She was trying to remember where exactly the dining table was when she felt something soft, like a spiderweb, pass over her bare thigh.

The dog’s name came out just a few decibels below a shriek. As Kendra collided with the counter, Sam’s door swung open. Light spilled into the kitchen, exposing the dining table, its chairs, and the butcher block island like prisonbreakers under a spotlight.

“There you are,” said Sam. The door widened to allow Misty, tail wagging, to click inside.

“She scared me!” cried Kendra. Stupid. There she was, sneaking around in the dark. “God, I’m sorry.” Her heart was racing. Keeping her arm folded tightly against her chest, she tried to catch her breath. “I would have texted but I didn’t get your number.”

Sam’s socks and boxer briefs were the same faded black, but her t-shirt was white. Piercings tented it like twin knives under a sheet. “I don’t have a phone, remember?” She pointed to the dining table. “Except the landline.”

“Oh,” said Kendra. Beneath her towel, her flush seemed to go everywhere, from her ribs to the backs of her thighs.

She was locking her bedroom door behind her when she remembered the aspirin. The tears finally came, but she wasn’t going back out there tonight. Leaving her towel in a crumble on the floor, Kendra swaddled herself in her comforter, laid down on the mattress, picked up her phone, and opened Cyte.

Kendra’s routine at the farmhouse quickly took shape. Early in the morning, while the crows screamed in the dark, she was awakened by the smell of Sam’s coffee. Warm under her comforter, she opened Cyte.

For a moment, its cheesy hero—Your Life, Your Content—would throb beside banner images of carefree multiracial people, none of them older than she. Then it would disappear, revealing her profile. Her mutuals in different time zones would have updated while she slept, and sometimes there was already fresh personal content from the day before. There was Kendra, tightening her ponytail at the gas station or impatiently tapping the countertop at the university library. No matter how poor the quality of the surveillance footage, she looped every video, scrutinizing her clothes, her posture, her ass. She’d gained weight since the breakup, though she refused to get on the scale to find out just how much. It would be so easy to let yourself go without Cyte, she often thought. What had people done before it existed?

But at that early hour, not even Cyte could hold her attention for long. Lulled by the sounds of Sam getting ready for work, Misty clicking at her heels, Kendra would eventually fall asleep again, her phone glowing on the comforter beside her.

When her alarm went off a few hours later, Kendra would get out of bed, reheat the coffee, and get to work. By then, Sam would be long gone. She was part of the maintenance crew on campus, mowing lawns and spraying bugs. She and Misty would return in the early afternoon, as the sun was sinking into bruise-colored clouds. Sam would shower while Kendra had lunch, her first meal of the day, with Misty waiting outside the bathroom door. Once, Kendra offered her a glob of low-fat hummus. The dog sniffed the air, then looked away.

If Kendra didn’t have to go to campus after lunch, she would review her notes while Sam read and smoked on the porch, or rummaged around in the woodshed, Misty at attention under the carport. Sometimes, when she needed a break, Kendra would get up to walk the perimeter of the farmhouse, peering out every window except the ones in Sam’s bedroom. All of them opened onto the same view: gravel, grass, the wall of trees. Sometimes she couldn’t see Sam and Misty. Were they in the orchard? If the pickup was still there, where else would they be? All would be quiet until, a little before sundown, she heard them on the porch—the scrape of boots, the scratch of nails.

As Sam had told Kendra while she was signing the rental agreement, her room was a sublet. The farmhouse and truck were rented and leased, respectively. She didn’t know who the orchard belonged to.

“We always meant to buy once we’d saved up enough,” Sam said, tapping the porch with her boot. On the piece of paper, their initials overlapped like kindling. “Get our little farm off the ground.”

Kendra didn’t think to ask what they had wanted to grow. “But it’s still okay for you to walk around out there?” she said, gesturing toward the trees. “No one minds?”

“I mean, I wouldn’t if I were you,” said Sam, rubbing a callus at the base of her ring finger. Kendra couldn’t tell if she was joking. She waited for her to go on, but she didn’t.

After dinner, Sam usually went to her bedroom, leaving every hour or so to smoke on the porch. If she was working in the kitchen, Kendra would occasionally catch glimpses of the ancient desktop, vintage TV, and cheap shelves distended by hundreds of paperbacks. Sam’s room was smaller than hers and looked even more so because of the king-size bed—far too large for Sam and Misty, who to Kendra’s disgust was permitted to join her there. She felt sorry for Sam, and wondered if she should offer to pay more for her room, luxurious in comparison, especially considering Sam’s dream of someday owning the farmhouse. But then she thought about Mexico City and didn’t. It would be one thing, of course, if Sam asked her to pay more. She’d probably refuse such an offer, anyway.

After her own dinner—a can of soup with gluten-free crackers if she’d been to campus, hold the crackers if she hadn’t—Kendra graded papers with Netflix on in the background before getting back into bed to end the day as she began it: scrolling Cyte, though now with the bottle of gin she kept in her night stand. This was how she learned that not only were the cameras in the kitchen and on the front porch functional, but that they weren’t the only ones in the farmhouse.

Thank you for joining me as I try a little something different. If you’d like to support my work—most of which is free—you can subscribe, buy my books, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

August 19, 2025

The farmhouse

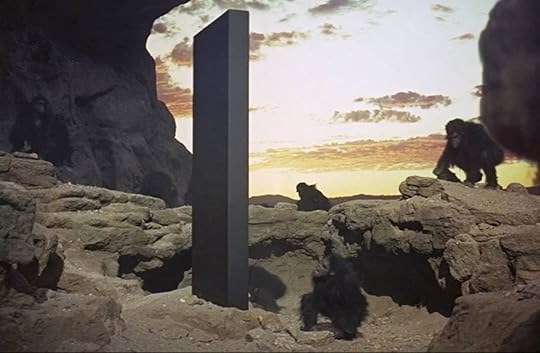

Image credit: fralo

Image credit: fraloPerhaps you can help me settle something: did I write a ghost story? The farmhouse begins when Kendra, a newly single college student, moves to the edge of town in hopes of escaping the local dyke drama.

Let me know what you think.

“But there’s nothing here about the roommate,” Noah said. He handed her the phone and returned his attention the joint he was rolling. When he leaned forward, his thermal flared where the backrest met the seat of the chair, exposing his fatless lumbar spine to the morning chill.

Kendra sighed. She scrolled through the ad again. private bed & bath in shared farmhouse. There was a name—Sam—but no other personal details except for two short sentences: no pets. i have a dog.

“Not not a red flag,” she admitted, enlarging her favorite photo. “But it’s perfect. And I like dogs.” She hadn’t intended to move in with some random man, but she’d pledge a frat for this big, beautiful bedroom at nearly half her budget.

Noah licked the translucent paper. “Well,” he said, “you’re the one who wants to get away from it all.”

By the time she passed the lightning-split oak that marked the city’s southern limit, Kendra was lost. Her destination refused to populate and the directions from her terse email exchange with Sam didn’t account for the access roads that disappeared into the trees, by now stripped of their fruit by the harvesters and their leaves by the season. She was almost twenty minutes late before she found the right turnoff, almost thirty when she noticed the mailbox staked beside a narrow driveway.

The chassis of an older car would have bounced as it descended to the one-lane gravel road, but her mom’s hand-me-down hybrid managed the transition with stiff alacrity. Gingerly accelerating beneath a canopy of bare black branches, Kendra followed the driveway’s long curve against the interstate, then its right turn into a clearing that, from the road, was hidden from view. In the clearing was the farmhouse, the squat blue center of three concentric rings: first gravel, then grass, then the trees, all dripping like a million broken shower heads.

Kendra zipped up her jacket and opened the door. Darkened by the morning’s rainfall, the gravel bore her weight without a sound. Somewhere overhead, a crow coughed. She had been expecting a busy open house—the rental market in her private college town had only gotten more competitive since she moved here for undergrad—but other than a green pickup parked under a rundown carport, hers was the only vehicle. Beneath the pickup, a big sandy mutt reclined in a patch of dust. At Kendra’s whistle its ears moved, but its snout remained between its forepaws, pointing at the trees to the east of the farmhouse.

Like the carport, the farmhouse had seen better days. The porch peeled like a skin disease, the black-and-white latticework around its base as gap-toothed as a mid-game go board. Next to it was a rust-stained woodshed, its doors hanging drunkenly on their hinges. Nearby, some empty tomato trellises straddled sterile mounds of earth. “Farmhouse” was clearly aspirational. The place was more like a forgotten hillbilly cemetery.

Sighing, Kendra leaned back into the car for the manila binder with her rental paperwork. Clipped to the top was her photo from Walnut Park last summer. She had always thought that Caroline’s artsy photography made her look washed out, but Noah didn’t agree. “You look pretty in this one. Prettier than you actually are, no shade.” Kneeling on the driver’s seat, she opened her phone, sweeping past a text from him (how did it go?) and a few yellow Cyte notifications.

A door slammed like a gunshot. When Kendra turned her head, Sam was already halfway across the clearing. “You made it!” she exclaimed, teeth emerging. “I was worried you weren’t going to show.”

Allowing her fingers to be folded into the cold, square handshake, Kendra smiled, too. Not only was Sam a woman, but she was a woman with a crew cut and work boots. Too manly for her taste—but wasn’t she here to get away from the town’s tiny lesbian scene, where every breakup seemed to involve at least a dozen people while somehow lasting longer than the relationship it ended? Out in the boonies was the farthest she could go without dropping out altogether, but she was scared to do it alone, and Noah refused to give up his one-bedroom to join her. If she had to share a home with somebody, the only dyke in town who wasn’t involved in the drama (or her drama, anyway) was as good as it was going to get.

Before she could reply, something hard and wet slid across the back of her thigh. Kendra’s first thought, as she bashed her elbow against the hybrid, her foot dragging a runnel of grit across her clean white sock, was that she was pissing herself.

Laughing, Sam seized the dog’s collar. “Misty loves making friends,” she said, digging her fingers into the short, sandy fur.

Kendra’s elbow hurt, but she laughed, too. “Misty,” she repeated, her eyes watering. Embarrassed, she straightened her skirt, the one with the stain you could see if the light was right. Could Sam tell she was living out of her suitcase? No, she decided, regaining herself, the butch wouldn’t notice something like that.

Quicksilver suddenly boiled across Kendra’s pink cheeks, ruining the photo. It was raining. “Oh,” she said, “my application—”

“I’m sure it’s all there,” Sam said, waving the folder away. “Let’s get inside.” Misty was already under the pickup again, staring at the trees.

To Kendra’s relief, the farmhouse was more welcoming inside. Though there was dog hair on the couch, the rustically handsome furniture—a coffee table, a stunning sideboard by the fireplace—was polished to a shine. The walls were strangely bare, but there was a framed photo of Misty on the coffee table and, on the sideboard, another of a jumpsuited baby in the arms of a headless woman. Like Sam, it smelled pleasantly of leather and tobacco, with an undercurrent of some unidentifiable flower.

Running her fingers through her damp hair, or what there was of it, Sam repeated the terms of the ad. With her high forehead, heavy jaw, and naturally straight teeth (orthodontia always had a look, didn’t it, thought Kendra), she reminded her of Hilary Swank in that lesbian movie. Kendra followed her to the kitchen, watching as she opened the golf ball-textured refrigerator, gestured to the range, and pointed out the camera nestled near the ceiling.

“It doesn’t work,” Sam said. “Hope that’s okay. It was here when we moved in, but we’re so far out I never saw the point in replacing it. And I’m sort of a Luddite. I don’t even have a cell phone.”

She glanced at the one in Kendra’s hand, which she didn’t remember taking out. She shoved it back in her purse, feeling a thrill of unease. “No problem,” Kendra said. She couldn’t remember life without cameras in the house, though her older brother, Tim, probably could. Sam’s age was hard to determine. Plaid flannel, analog wristwatch, hips disguised in men’s denim—was she a relic, or just retro? Kendra would have believed that Sam was twenty years older than she, or just a few solar rotations past her Saturn return.

“Great.” Sam was smiling again. “Your room’s back here.”

There it was, beyond the sparkling sink and the butcher block island. Kendra followed Sam through a doorway, stepping down a few inches from the kitchen tile to beaming parquet wood. Except for a power drill by her foot, the freshly painted bedroom was empty. The windows, each broader than her wingspan, framed the gravel, the grass, and a corner of the woodshed, beyond which the orchard crested like a frozen tsunami. On a cloudless spring day, it would shimmer with pink-hearted blossoms. Kendra already knew where she wanted to put her desk.

“It’s nice,” she said, trying to sound unimpressed. “Did someone just move out?” There had to be something wrong with it—a toilet that never stopped running or a pernicious case of black mold. But the door that led to the private bathroom was open, revealing a tranquil eggshell cove, complete with a tub mounted on enameled basilisk’s claws.

Sam had stopped smiling. “My ex.”

Kendra pictured a prairie femme with messy braids and muddy clogs. Sam and her homespun companion would have Uhauled to the farmhouse years ago with dreams of IVF and hers-and-hers tombstones. What had the irreconcilable difference been? The femme’s Etsy addiction? The butch’s wandering eye? She wanted to tell Sam about Caroline, both to out herself and to let her know she wasn’t the only one to have gone through a breakup recently.

But there it was again: in a single rapid movement, the slick yet rigid muscle had ascended from her Achilles’ tendon to the ticklish square inch directly behind her knee. Kendra caught herself against the doorframe, realizing as she did that it was impossible to push the dog’s muzzle away without just a hint of violence.

When they returned to the front porch, the rain had stopped. A crow landed on a tomato trellis and cocked its head. Her tail erect, Misty leapt down the steps and sprinted across the gravel.

They signed the paperwork on a small table beside a half-full ashtray and a few mini lighters. After Kendra’s final initial, Sam offered her a cigarette. She declined, a little too politely, before pointing at the camera above the door. “There’s another one.”

“God, is that thing still there?” Sam looked up over her shoulder, her hands cupped around her mouth. “One of these days I’ll get around to taking them down.”

“I’m moving in this weekend!” Kendra announced. She snatched a carrot and poked his shoulder with it. “Now you’ll never have to cook me your gross Ayurvedic food ever again.”

“Finally!” Noah exclaimed. As little as he ate, the kitchenette was his favorite place to be. Water simmered on the stove, Kylie whispered from the bluetooth speaker, and a Christmas cactus budded, a month early, on the windowsill above the sink. “I was starting to think you dumped her so you could force me to be your maid.”

Kendra stuck out her tongue. “And guess what?”

“What?” Noah was focused on the cutting board, his slender knife strokes onbeat with the music.

“I got the dyke discount,” said Kendra. She nibbled the carrot. “She’s charging me even less than what she put in the ad. I’m going to save so much money.” She wanted to go to Mexico City in the summer, for a month at least this time.

“Seriously? Why would she do that?”

Kendra shrugged. “Maybe everyone else who applied was straight.”

“Oh, for sure.” Now Noah leered at her, his cuts slowing.

“Shut up.”

“Just you two girls out there all alone—”

“Noah!” she cried, poking him with the carrot again.

Grimacing like a scream queen, he was archly raising the knife above his head when the water boiled over behind him, blanketing the window with steam.

Thank you for joining me as I try a little something different. If you’d like to support my work—most of which is free—you can subscribe, buy my books, or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

August 12, 2025

Body scan

Brain: When I was in high school, my therapist said that eating disorders were about control. Control over who or what? Was this control in excess, or was it lacking? Could something be done about it, or was knowing that my problem was “about” something other than pounds or calories supposed to be the solution to my problem? He never explained. Strange, because my therapist loved to talk. He also did sessions with my mom, and since he told me her secrets, I could rest assured he told her mine.

August 10, 2025

A flaming queen prancing

Regarding Frank Ripploh’s Taxi Zum Klo (1981)—a classic of queer cinema about a gay schoolteacher living in Berlin at the dawn of the HIV/AIDS pandemic—The Siskel & Ebert Review begins somewhat predictably: by highlighting one of the scenes most relatable to straight people, in which Ripploh’s semi-autobiographical Frank fusses about feeling controlled by his homemaking lover, the sweet Bernd (Bernd Broaderup), over a dinner of baked chicken. “That’s exactly what drives me nuts, that you always work so hard,” complains Frank, clearly feeling himself to be the victim of a butch nag.

When the clip ends, Gene Siskel gives us a sympathetic been there expression. “A lot of couples in the movies have had that kind of argument,” he observes.

August 7, 2025

How can I "---" at a time like this?

Earlier this week, Rashid Khalidi, Columbia University’s Edward Said professor emeritus, announced that he wouldn’t be teaching his fall course after the school agreed to pay a $200 million settlement for trumped-up charges of antisemitism (that is, anti-Zionist advocacy on campus) and “woke ideology.” How can an anti-Zionist professor continue teaching modern Arab studies at a time like this? As Khalidi wrote for The Guardian, “[Columbia’s] draconian policies and new definition of antisemitism make much teaching impossible.”

“How can I write at a time like this?” I used to think this was a rhetorical question. Of course a writer could write, an artist create, a lover love, whenever they wanted. The problem was times like these—of war and suffering—in which doing so became vulgar or inconsiderate or wasteful. Naively, I was conflating ethics and propriety, philosophy and manners. As Professor Khalidi’s situation illustrates, however, times like these have implications that are undeniably practical in nature. How could they be otherwise? This isn’t a hypothetical, a thought experiment, a query for Emily Post. An assault on life is an assault on meaning, on which art and love depend.

In the past 24 hours, a 2-year-old Palestinian girl who died of malnutrition in the al-Mawasi area, a supposed safe zone. How can we speak at a time like this? Write? Take action? Be holy? I can’t offer you any answers (although I’ve certainly tried). But lately, as the people in what you might call my immediate digital vicinity have returned to this line of questioning, I’ve taken heart in their refusal to give up on it.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Since 2023, the vast majority of Gaza Strip has been bombed and destroyed, displacing around 2 million people who need shelter. The Sameer Project is raising funds for tents, cash, and other vital supplies. Screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content. Please share the fundraiser in your networks!

July 28, 2025

The Village Shim

My boyfriend and I have this bit about how, back in the old days, we both would have been the Village Shim. In my head, this character exists in the same realm as those caveman cartoons with the leopard-print onesies and turkey bone-shaped clubs, an ahistorical cartoon so deep-fried that you can almost pretend it isn’t secretly racialized (but then, what isn’t). Of course, if we’re going to be literal about the old days, Nes and I would have been shimming in very different villages—my ancestry is European and his is African—so for the purposes of this bit, in which we know each other1, there has to be some suspension of disbelief. We would have both had leopard-print onesies, although mine would probably have had a pink bow.

The bit sticks, I think, because while neither of us know what our lives would have been like a thousand years ago, or whatever, it’s fun to pretend that we would have been together and that our genderweirdness would have had a social designation that wasn’t especially alienating or dangerous. That, while maybe a little unusual, it would have been more-or-less legible to the people around us, and that we would have had a role to fulfill based on this observable but minor variance2. But even on its own terms, this fantasy doesn’t hold water—the Village Shim is, definitionally, a weirdo, at odds with the normal genders in a similar state of difference as the Village Idiot, a humiliated figure of ableism upon whom our bit depends. Even when fantasizing about a life with less social friction, I’m unable to do so without reifying the kind that already exists.

One time I hooked up with this beautiful real estate guy who came from lots of money. We had good chemistry, and he forgot himself with me. With the easy intimacy of straight men (I’m the only man a relationship needs, he said proudly), he spoke about the strange self-awareness of being a tall, handsome, rich Black man who felt welcomed and threatened in equal measure every time he entered a room. He mentioned his desire to travel to South Africa for all the fat-assed women there, before abruptly silencing himself, perhaps embarrassed to have shared a heterosexual thought with me, the decidedly not-fat-assed white boy he’d just bred. He didn’t know that I was used to this. Straight men call me their trophy, their fantasy, their ideal, but they would never introduce me to their parents. They come into my home, lie in my bed, and tell me everything. I’m the male friend they can fuck and the woman they can trust (or is it the other way around). I am everything in one person—like a lot of trans people, I’ve been demeaned with the best of both worlds too many times. Don’t stop, he said, when, for a moment, I ceased stroking his leg. He wanted to know if I could cook.

I worry that I’m making him sound as if he wasn’t absolutely charming, as if he didn’t walk into my house, smile, and throw open his arms, saying, Let me just look at you for a moment. When someone has been deeply loved by their family, they shine like a lighthouse for their entire lives. And yet he needed something from me. What does it feel like to be need as a woman? As a man? I know, but I will also never know.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky

I don’t typically share fundraisers for people I know personally, but my friend Maddie is in a tight spot. I want to tell you all the reasons why Maddie deserves your help, but she would be the first to insist that healthcare isn’t a matter of “deserving,” and it’s sick that any of us are forced to behave as if it is. If you have a few dollars to send Maddie’s way, screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

1Although this undermines the singular nature of Village Shim-ness.

2Which isn’t to say that, here and now, trans people aren’t absolutely legible. The pretense that we aren’t is one of the more insidious aspects of the bigotry that endangers us.

July 18, 2025

From ape to angel

Beginning in the early 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke co-wrote the screenplay and novelization of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the culmination of an techno-artistic project as epic as its narrative1. Clarke, a scientist and lifelong proponent of space travel, believed that earth is man’s purgatory between the oceans and the heavens—“a staging ground for our ascension from ape to angel.” Coming from a man knighted by the British empire, a force whose intercontinental conquest of billions of people and countless ecosystems continues into the postcolonial era, it’s a pretty encapsulation of a perniciously white supremacist philosophy, one that we’re all paying for with every manifestation of climate change. Elon Musk could never express himself so articulately, but it’s not difficult to connect the dots between SpaceX’s explosions and Clarke’s fantasies of the final frontier.

Because you and I, we’re smart people, right? We read. We’re woke. We know, even if people like Clarke didn’t, that white supremacy and colonialism and capitalism are what got us into this mess; that the white-centric sci-fi dystopias of the past century’s popular books and movies have been the lived experience of Indigenous, colonized, and enslaved people since at least 1492; and that the only way to mitigate this global holocaust’s expansion (because there’s no going back now) is returning stewardship of the land to the people it was stolen from. So when I picked up Jordan Thomas’s When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World, I expected to learn about the science of megafires—wildfires that behave in ways that would have been nearly impossible when I was a child—and the experience of the Los Padres Hotshots—a unit of America’s special forces firefighting service—which I did. I expected to feel depressed and panicked by unfamiliar details about the severity and speed of the climate crisis, which I also did. But I didn’t expect much more than that. Like, I have all this #landback stuff on lock, my friend, you don’t have to convince me! I get it!

But somehow, with Thomas’s artful arrangement of memoir, reportage, and research, I became even more certain of something I hadn’t realized I was only believing in degrees. I already knew a tiny bit about the history of fire suppression in America, the creation of “arson” and “firefighting” as pretexts for oppression in the genocide of Indigenous people. But Thomas contextualized it with scientific and anthropological history—from the vital role that fire plays in every single ecosystem, to its intentional use in human cultures all over the world going back thousands of years, to its suppression in the New World, to the Indigenous resistance of the violent destruction of this ancient science. For years now, ever since the first megafires threatened my home in Northern California, I’ve been craving a feeling of resignation. Then at least, I used to think, I could numb out the fear and anguish and rage. This book gave me something much more useful: acceptance.

Thomas writes, “From a certain perspective, these [new] fires could be seen as aligning ecosystems with an emerging planet—transitioning from forest to brush, brush to grassland, grassland to desert, until there is no life left to burn.” This is terrifying. But in the face of this reality, the people with the most to fear (because they have already lost everything, or almost) have maintained a powerful integrity, even as increasingly desperate fire management programs become more amenable to Indigenous practices like regular controlled burns, anathema in an ecosystem transformed into a powder keg by centuries of abuse and exploitation. Despite the urgent need to act, capital still protects itself with policies that are only superficially about cooperation with Indigenous scientists and caretakers, which are assiduously rejected for the cynical compromises they are: the state will not rescue us (and who is “us?”). “Saving what for many of our people is a dystopia is not a very good strategy for allyship,” points out Kyle Powys Whyte, a Potawatomi philosopher and environmental scholar.

Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, When It All Burns also begins with apes. Thomas tells the story of primatologist Jill Pruetz, who discovers while living with a troop of chimpanzees in the grasslands of Senegal that her hosts are unafraid of wildfire. “As the fire approached them, the chimpanzees didn’t retreat—they stood and filed toward the flame front.” Like chimpanzees, many animals that evolved alongside humans are attracted to wildfire, which produces food and fertilizes the land—having developed a genetic mutation that allows us to eat cooked food, as humans, it’s literally in our DNA. “It’s not so much that humans domesticated wildfires,” Thomas writes, “but that wildfires domesticated us.”

“Then, just a few centuries ago,” he continues, “a small group of humans began putting these fires out.” As a white Californian, I had never questioned the notion that wildfire is to be avoided at all costs—why should I, when such a fear is “natural?” Over the course of 300 pages, Thomas upended everything I thought I knew about this subject in a way I can only describe as a radicalization. In search of solutions to the political gridlock surrounding prescribed burns, which settlers still view with suspicion, Thomas joins a state forester to learn how she’s organizing her community to embrace the old ways, the ones predating European colonization. While her work is slow going—“People view forest management as dealing with trees, but so much of it is dealing with emotions,” she says—she tells him that climate change no longer keeps her up at night. “This is my forest,” she says. “And I’m doing everything I can to ensure that, when it burns, it survives intact. This is one small piece of the problem, but it’s something I can control.”

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky

I don’t typically share fundraisers for people I know personally, but my friend Maddie is in a tight spot. I want to tell you all the reasons why Maddie deserves your help, but she would be the first to insist that healthcare isn’t a matter of “deserving,” and it’s sick that any of us are forced to behave as if it is. If you have a few dollars to send Maddie’s way, screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

1Kubrick’s fame for his obsessive productions begins with 2001. For years before shooting, this man was inventing colors and chemicals and machines. He and Clarke were anticipating technology that didn’t come about until decades later. And out of it came one of the best movies ever made. Makes me cry like a baby.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 52 followers