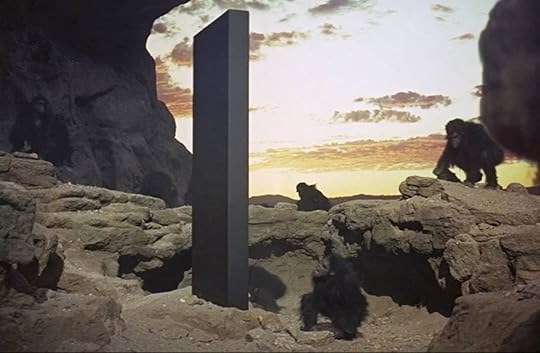

From ape to angel

Beginning in the early 1960s, Arthur C. Clarke co-wrote the screenplay and novelization of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the culmination of an techno-artistic project as epic as its narrative1. Clarke, a scientist and lifelong proponent of space travel, believed that earth is man’s purgatory between the oceans and the heavens—“a staging ground for our ascension from ape to angel.” Coming from a man knighted by the British empire, a force whose intercontinental conquest of billions of people and countless ecosystems continues into the postcolonial era, it’s a pretty encapsulation of a perniciously white supremacist philosophy, one that we’re all paying for with every manifestation of climate change. Elon Musk could never express himself so articulately, but it’s not difficult to connect the dots between SpaceX’s explosions and Clarke’s fantasies of the final frontier.

Because you and I, we’re smart people, right? We read. We’re woke. We know, even if people like Clarke didn’t, that white supremacy and colonialism and capitalism are what got us into this mess; that the white-centric sci-fi dystopias of the past century’s popular books and movies have been the lived experience of Indigenous, colonized, and enslaved people since at least 1492; and that the only way to mitigate this global holocaust’s expansion (because there’s no going back now) is returning stewardship of the land to the people it was stolen from. So when I picked up Jordan Thomas’s When It All Burns: Fighting Fire in a Transformed World, I expected to learn about the science of megafires—wildfires that behave in ways that would have been nearly impossible when I was a child—and the experience of the Los Padres Hotshots—a unit of America’s special forces firefighting service—which I did. I expected to feel depressed and panicked by unfamiliar details about the severity and speed of the climate crisis, which I also did. But I didn’t expect much more than that. Like, I have all this #landback stuff on lock, my friend, you don’t have to convince me! I get it!

But somehow, with Thomas’s artful arrangement of memoir, reportage, and research, I became even more certain of something I hadn’t realized I was only believing in degrees. I already knew a tiny bit about the history of fire suppression in America, the creation of “arson” and “firefighting” as pretexts for oppression in the genocide of Indigenous people. But Thomas contextualized it with scientific and anthropological history—from the vital role that fire plays in every single ecosystem, to its intentional use in human cultures all over the world going back thousands of years, to its suppression in the New World, to the Indigenous resistance of the violent destruction of this ancient science. For years now, ever since the first megafires threatened my home in Northern California, I’ve been craving a feeling of resignation. Then at least, I used to think, I could numb out the fear and anguish and rage. This book gave me something much more useful: acceptance.

Thomas writes, “From a certain perspective, these [new] fires could be seen as aligning ecosystems with an emerging planet—transitioning from forest to brush, brush to grassland, grassland to desert, until there is no life left to burn.” This is terrifying. But in the face of this reality, the people with the most to fear (because they have already lost everything, or almost) have maintained a powerful integrity, even as increasingly desperate fire management programs become more amenable to Indigenous practices like regular controlled burns, anathema in an ecosystem transformed into a powder keg by centuries of abuse and exploitation. Despite the urgent need to act, capital still protects itself with policies that are only superficially about cooperation with Indigenous scientists and caretakers, which are assiduously rejected for the cynical compromises they are: the state will not rescue us (and who is “us?”). “Saving what for many of our people is a dystopia is not a very good strategy for allyship,” points out Kyle Powys Whyte, a Potawatomi philosopher and environmental scholar.

Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, When It All Burns also begins with apes. Thomas tells the story of primatologist Jill Pruetz, who discovers while living with a troop of chimpanzees in the grasslands of Senegal that her hosts are unafraid of wildfire. “As the fire approached them, the chimpanzees didn’t retreat—they stood and filed toward the flame front.” Like chimpanzees, many animals that evolved alongside humans are attracted to wildfire, which produces food and fertilizes the land—having developed a genetic mutation that allows us to eat cooked food, as humans, it’s literally in our DNA. “It’s not so much that humans domesticated wildfires,” Thomas writes, “but that wildfires domesticated us.”

“Then, just a few centuries ago,” he continues, “a small group of humans began putting these fires out.” As a white Californian, I had never questioned the notion that wildfire is to be avoided at all costs—why should I, when such a fear is “natural?” Over the course of 300 pages, Thomas upended everything I thought I knew about this subject in a way I can only describe as a radicalization. In search of solutions to the political gridlock surrounding prescribed burns, which settlers still view with suspicion, Thomas joins a state forester to learn how she’s organizing her community to embrace the old ways, the ones predating European colonization. While her work is slow going—“People view forest management as dealing with trees, but so much of it is dealing with emotions,” she says—she tells him that climate change no longer keeps her up at night. “This is my forest,” she says. “And I’m doing everything I can to ensure that, when it burns, it survives intact. This is one small piece of the problem, but it’s something I can control.”

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky

I don’t typically share fundraisers for people I know personally, but my friend Maddie is in a tight spot. I want to tell you all the reasons why Maddie deserves your help, but she would be the first to insist that healthcare isn’t a matter of “deserving,” and it’s sick that any of us are forced to behave as if it is. If you have a few dollars to send Maddie’s way, screenshot your donation of any amount and I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content.

1Kubrick’s fame for his obsessive productions begins with 2001. For years before shooting, this man was inventing colors and chemicals and machines. He and Clarke were anticipating technology that didn’t come about until decades later. And out of it came one of the best movies ever made. Makes me cry like a baby.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 52 followers