Edward Feser's Blog

August 29, 2025

Maimonides on negative theology

Negativetheology (also known as apophatic theology) is the approach to understandingthe divine nature that emphasizes that what we know about God is what he is notrather than what he is. One might takethe strong view that all of ourknowledge of God’s nature is negative in this way, or the weaker position thatmuch (but not all) such knowledge is negative. The medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) is amongthe most famous of negative theologians. He takes the stronger position. More precisely, his view is that when we predicate something of God, weare describing either his effects in the world of our experience, or the divinenature itself, and in the latter case we must understand our predications in apurely negative way.

Negativetheology (also known as apophatic theology) is the approach to understandingthe divine nature that emphasizes that what we know about God is what he is notrather than what he is. One might takethe strong view that all of ourknowledge of God’s nature is negative in this way, or the weaker position thatmuch (but not all) such knowledge is negative. The medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) is amongthe most famous of negative theologians. He takes the stronger position. More precisely, his view is that when we predicate something of God, weare describing either his effects in the world of our experience, or the divinenature itself, and in the latter case we must understand our predications in apurely negative way.For example,suppose we say that God is merciful toward the righteous and takes vengeance onthe wicked. For Maimonides, the rightway to understand this is as saying that God causes the righteous to berewarded and the wicked to be punished. It is a statement about the effects of God’s actions, not about thedivine nature itself. Or suppose we saythat God is omnipotent. For Maimonides,this should be understood as a statement to the effect that there are in God nolimitations of the kind that constrain the power of created things. It is a statement about the divine nature,but only about what is not true ofit, rather than a positive attribution.

In hisfamous The Guide of the Perplexed,Maimonides defends Aristotelian arguments for the existence of a divine firstcause. He also defends the doctrine ofdivine simplicity, according to which God is in no way composed of parts. It is in light of this fact about the divinenature, says Maimonides, that we can see that our knowledge of it can only benegative. He argues as follows:

It has been proved that God exists by necessity and that Heis non-composite… and we can apprehend only that He is, not what He is. It is therefore meaningless that He shouldhave any positive attribute, since the fact that He is is not something outsideof what He is, so that the attribute might indicate one of these two. Much less can what He is be of a compositecharacter, so that the attribute could indicate one of the parts. Even less can He be substrate to accidents,so that the attribute could indicate these. Thus there is no scope for any positive attributes in any waywhatsoever. (Book I, Chapter LVIII, atp. 80 of theabridged Rabin translation)

Let’s unpackthis. In this passage, it seems,Maimonides tries to show that divine simplicity all by itself entails anexclusively apophatic theology. Howso? Start with the point he makes in themiddle of the paragraph, concerning the proposal that to speak of a divinepositive attribute “could indicate one of the parts” of God. Obviously this would be ruled out by divinesimplicity, which denies that God has any parts. Nor, as he says at the end of the passage,could a positive attribute be an accident inhering in the divine substrate,because divine simplicity also rules out any distinction in God betweensubstrate and accidents.

The thirdoption Maimonides considers and rules out is the proposal that a divinepositive attribute might be identifiable with either “the fact that He is” or “whatHe is” – that is to say, with either God’s existence or his essence. The idea here seems to be that someone whothinks we can predicate positive attributes of God might suppose that God’sexistence is a positive attribute distinct from his essence, which we canpredicate of that essence; or that God’s essence is a positive attributedistinct from his existence, which we can predicate of that existence. And the trouble with this proposal,Maimonides says, is that given divine simplicity, there is no distinctionbetween God’s essence and his existence. They are one and the same thing.

Theargument, then, seems to be that these three proposals would be the only waysto make sense of positive divine attributes, but all three are ruled out bydivine simplicity; therefore, as he concludes at the end of the passage, “thereis no scope for any positive attributes in any way whatsoever.”

The readermight wonder, though, exactly why we should regard these three as the onlyoptions. Some remarks Maimonides makesearlier in Book I of the Guide indicatethe answer. In Chapter LI, he writes:

It is thus evident that an attribute must be one of twothings. Either it is the essence of thething to which it is attributed, and thus an explanation of a term… Or theattribute is different from the thing to which it is attributed, and thus anidea added to that thing. Consequentlythat attribute is an accident of that essence. (p. 67)

It is nothard to see why Maimonides would deny that God has attributes in the secondsense, for that would be ruled out by the thesis that there is, given divinesimplicity, no distinction in God between substrate and accidents. But what about attributes in the first sense,that is to say, an attribute understood as “the essence of the thing to which it is attributed, and thusan explanation of a term”? And whatexactly does Maimonides mean by this?

Heillustrates the idea with the example of asserting that “Man is a reasoninganimal.” When we predicate of man theattribute of being a reasoning animal, we are really just picking out theessence of man, and thereby giving an “explanation of [the] term” (i.e. theterm “man”). The attribute in this caseis nothing different from the essence or nature of the thing to which we areascribing the attribute. To predicate ofGod a positive attribute in this sense, then, would be to explain the meaningof “God” by stating the divine essence. Yet Maimonides says that even here, “this kind of attribute we rejectwith reference to God” (p. 67). Why?

The subsequentchapter of the Guide, Chapter LII,indicates the reason. Suppose we try todefine God, in something like the way we define man as a reasoning animal. This, Maimonides says, would imply that Godhas “pre-existing causes,” which as first cause he cannot have (p. 68). How so? Maimonides’ meaning here seems to be this. When we define man as a reasoning animal, weare identifying him as belonging to a certain genus (namely, animal) and as set apart from otherthings in that genus by a differentia (namely, reasoning). Now, in a sense,animality and rationality are thus priorto man, and thus they are causes, of a sort, of his being. Since God is uncaused, then, he cannot bedefined in terms of a genus and a differentia. (Again, this seems to me to be what Maimonidesis getting at, though he doesn’t spell it out in the relevant passage inChapter LII.)

Maimonidesthen says that another thing we might be doing when predicating an attribute ofsomething in the sense of defining it is describing it in terms of part of its essence. We do this, for example, when we say that man is an animal. But this too cannot be what we’re doing inthe case of God, because given divine simplicity, there are no parts to God’sessence.

Thus does Maimonidesclaim to show that we can say nothing positive about the divine nature. But some readers may think he would stillneed to say more in order to make the case. And they would be right. For consider Aquinas’s alternative position. Like Maimonides, he strongly affirms divinesimplicity, holds that we cannot strictly define the divine essence, and takesmuch of our knowledge of God’s nature to be negative. But he rejects the extreme claim that we cansay nothing positive about him.

Aquinasargues that Maimonides’ position does not adequately account for talk aboutGod’s goodness, wisdom, and the like. He notes that the view that attributing goodness to God is really just a wayof saying that God is the cause of good things cannot explain why we say thatGod is good but not that God is a physical object – for, after all, God is thecause of physical objects too. Aquinascontinues:

When we say, “God is good,” the meaning is not, “God is thecause of goodness,” or “God is not evil”; but the meaning is, “Whatever good weattribute to creatures, pre-exists in God,” and in a more excellent and higherway. Hence it does not follow that Godis good, because He causes goodness; but rather, on the contrary, He causesgoodness in things because He is good. (SummaTheologiae I.13.2)

To be sure,this is not because there is some common genus to which God and other goodthings belong. Nor does Aquinas think wehave a clear idea of the nature of God’s goodness. Nor, given divine simplicity, does he thinkthat God’s goodness is distinct from his wisdom or his power or any of hisother attributes. Still, when we saythat God is good, we are in Aquinas’s view saying something positive about him,and something literally true.

How can thisbe? The answer has to do with Aquinas’sfamous view that not all literal language is either univocal or equivocal, butthat some is analogical, and thatthis is the case with predications of the divine attributes. When we say that God is good, we are notsaying that he is good in exactly the same sense in which we are good (which wouldbe to use “good” in a univocal way), nor are we saying that he is good in somecompletely unrelated sense (which would be to use “good” in an equivocalway). We are saying that there issomething in God that is analogous towhat we call “goodness” in us, even if it is not exactly the same thing.

Maimonideswould disagree. For him, when we applyto God’s nature the same terms we use to describe created things, we speakequivocally. This is true even when wesay that God exists, for God “shares no common trait with anything outside Himat all, for the term ‘existence’ is only applied to Him as well as to creaturesby way of homonymy and in no other way” (TheGuide of the Perplexed, Book I,Chapter LII, at p. 70).

This is nota dispute I will explore here. Sufficeit for present purposes to note that while Maimonides writes as if the controversyover whether God has positive attributes hinges on whether or not one acceptsdivine simplicity, that is not in fact the case. Rather, it hinges on whether or not oneaccepts that we can truly speak of God in analogical terms.

Relatedposts:

Dharmakīrtiand Maimonides on divine action

August 18, 2025

Diabolical modernity

Satantempted Christ to avoid the cross, and offer us instead the satisfaction of ourappetites, marvels or wonders, and political salvation – exactly what modernmarket economies, science, and liberal democracy promise us. In mylatest essay at Postliberal Order,I discuss Archbishop Fulton Sheen’s analysis of the diabolical, and the lightit sheds on the character of the modern world.

Satantempted Christ to avoid the cross, and offer us instead the satisfaction of ourappetites, marvels or wonders, and political salvation – exactly what modernmarket economies, science, and liberal democracy promise us. In mylatest essay at Postliberal Order,I discuss Archbishop Fulton Sheen’s analysis of the diabolical, and the lightit sheds on the character of the modern world.

August 12, 2025

Hanson on observation

According tothe conception of scientific method traditionally associated with FrancisBacon, science ought to begin with the accumulation of observations unbiased byany theoretical preconceptions. The ideais that only such theory-neutral evidence could provide an objective basis onwhich to choose between theories. Itbecame a commonplace of twentieth-century philosophy of science that this idealof theory-neutral observation is illusory, and that in reality all observationis inescapably theory-laden (to usethe standard jargon). That is to say,even to describe what it is we observe, we cannot avoid making use oftheoretical assumptions about its nature, circumstances, and so on.

According tothe conception of scientific method traditionally associated with FrancisBacon, science ought to begin with the accumulation of observations unbiased byany theoretical preconceptions. The ideais that only such theory-neutral evidence could provide an objective basis onwhich to choose between theories. Itbecame a commonplace of twentieth-century philosophy of science that this idealof theory-neutral observation is illusory, and that in reality all observationis inescapably theory-laden (to usethe standard jargon). That is to say,even to describe what it is we observe, we cannot avoid making use oftheoretical assumptions about its nature, circumstances, and so on.NorwoodRussell Hanson’s 1958 book Patternsof Discovery is commonly cited as a classic expression of thisview. And one way Hanson repays study isthat his treatment makes it clear that theory-ladenness does not by itself haverelativistic implications, contrary to what one might suppose from simplisticaccounts of contemporary philosophy of science.

To be sure,it can at first glance seemotherwise. As Hanson emphasizes, thereis a sense in which different observers operating with different backgroundassumptions can be said to see different things. One microbiologist looking through amicroscope at what’s on a certain slide might see a cell organ, while anothersees a bit of foreign matter that resulted from the staining process. One seventeenth-century astronomer looking atthe sun at dawn sees it move through the sky, while another sees the earth moving relative to the sun. And so on.

Many wouldreply that in reality, they do seethe same thing, but simply draw different inferences from it. The assumption here is that there are two things going on, a visual experienceon the one hand, and a separate act of interpretation of that experience on theother. But this, as Hanson influentiallyargued, is an illusion. One way thisillusory assumption is sometimes spelled out is by taking two perceivers tohave the same sort of retinal image, or the same physiological state, but thenimposing different interpretations on it. The problem here, as Hanson notes, is that a visual experience is simplynot the same thing as the having of a retinal image or other physiologicalstate:

Astronomers cannot be referring to these when they say theysee the sun. If they are hypnotized,drugged, drunk or distracted they may not see the sun, even though theirretinas register its image in exactly the same way as usual. Seeing is an experience. A retinal reaction is only a physical state –a photochemical excitation. Physiologists have not always appreciated the differences betweenexperiences and physical states. People,not their eyes, see. Cameras, andeye-balls, are blind. Attempts to locatewithin the organs of sight (or within the neurological reticulum behind theeyes) some nameable called ‘seeing’ may be dismissed… there is more to seeingthan meets the eyeball. (pp. 6-7)

Another waythe mistaken assumption in question is often spelled out is in terms of “sense-data.” The idea here is that the two observers havesimilar sense-data – describable, say, as their being “both aware of abrilliant yellow-white disc in a blue expanse over a green one” (p. 7) – andthat they then assign different interpretations to these sense-data. But this is simply not a correct descriptionof how visual experience goes in the normal case. Consider the famous Necker cube example (Fig.1 in the image above). If shown such animage and asked what he sees, a perceiver might simply say “That’s an icecube,” or “That’s an aquarium,” or “That’s a wire frame,” or any number ofother things. Context will likely play alarge role in determining his answer. For example, if the cube is part of a larger image that looks like a Scotchglass, he’s obviously more likely to describe it as an ice cube than as anaquarium. The point though, is thatthere are clearly cases in which the way he’d describe his experience is as“seeing an ice cube” – as opposed, say, to “seeing a set of lines, and thengoing on to interpret it as an ice cube.”

Of course,there can be cases in which theperceiver says the latter rather than the former. In thosecases there are two things going on, the experience and then a separateinterpretation of it. But there are not two things going in the ordinarycase. There’s just the one thing goingon, seeing an ice cube. Similarly, inthe case of the two astronomers, one of them might describe his perceptualexperience as “seeing the sun move” and the other as “seeing the earth move,”and with each of them there is just the one thing going on rather than anexperience together with a separate act of interpreting it.

Of course,the first astronomer would (as we now know) in this case be mistaken about what he sees. But that is irrelevant to the point, which isthat the content of his experience iscorrectly captured in the description “seeing the sun move,” rather than thedescription “seeing a yellow-white disc in a blue expanse” etc. Here too we can certainly imagine eccentriccases in which what a perceiver sees could accurately be described in that oddway – for example, if the perceiver had no idea of what the sun is. But obviously that is not what is going onwith a normal adult, let alone an astronomer. And if some astronomer did “react to his visual environment with purelysense-datum responses – as does the infant or the idiot – we would think himout of his mind. We would think him not to be seeing what is around him” (p.22).

Then thereis the fact that, even when we are dealingwith oddball cases like this, they still involve the application of concepts within the perceptual experience itselfrather than in some separate act of interpretation. We characterize the experience in terms of “ayellow-white disc” rather than “the sun,” but the characterization is internalto the experience rather than tacked on to it. As Hanson writes:

The knowledge is there in the seeing and not an adjunct ofit. (The pattern of threads is there inthe cloth and not tacked on to it by ancillary operations.) We rarely catch ourselves tacking knowledgeon to what meets the eye. (p. 22)

Moreover, ifperceptual experiences did notincorporate such knowledge, we would not be able to do with them the things wedo in fact do, and which science and common sense alike require us to be ableto do with them – namely, draw inferences from them and otherwise relate themto our larger body of background knowledge, including the scientific theorieswe test by way of perceptual experience. To quote Hanson again:

Significance, relevance – these notions depend on what wealready know. Objects, events, pictures,are not intrinsically significant or relevant. If seeing were just an optical-chemical process, then nothing we sawwould ever be relevant to what we know, and nothing known could havesignificance for what we see. Visuallife would be unintelligible; intellectual life would lack a visualaspect. Man would be a blind computerharnessed to a brainless photoplate. (p. 26)

This sort ofobservation is, of course, a longstanding part of modern critiques of naïveempiricism, from Kant’s dictum that “percepts without concepts are blind” toWilfrid Sellars’ attack on “the myth of the given.” And again, at first glance it might seem toentail a kind of relativism. If what we perceivealways reflects what we know (or take ourselves to know, anyway), but differentperceivers have different bodies of knowledge (or of what they take to beknowledge), how can they ever perceive the same things?

But Hansonalso makes it clear why such a relativistic conclusion does not follow. To say that there is a sense in whichdifferent observers may see different things – as in the examples involving theobject under the microscope, the sun at dawn, or the Necker cube – does notentail that there is not also a sensein which they see the samething. Suppose two people are looking atthe cube and one says “That’s an ice cube!” whereas the other says “That’s anaquarium!” It’s not as if there is nothing about which they agree. We can imagine the conversation continuing:“Do you at least agree that there are lines there?” “Of course!” Here too what they take themselves to know is intrinsic to theexperience rather than being tacked on in a separate act ofinterpretation. But in this case it is shared knowledge.

As Hansonwrites, “if seeing different things involves having different knowledge andtheories about x, then perhaps thesense in which they see the same thing involves their sharing knowledge andtheories about x” (p. 18). Disagreement takes place against a deeperlevel of agreement. Indeed, unless therewere some level of agreement (atleast concerning what exactly the disputeis about) there couldn’t be a disagreement in the first place. As Donald Davidson would later argue, even tomake sense of what another person is saying as language (whatever he issaying in that language), we need to be able to tie his utterances to aspectsof a shared environment, which entails shared beliefs about thatenvironment. Anticipating sucharguments, Hanson notes that error is the exception rather than the rule: “Wemay be wrong, but not always – not even usually. Besides, deceptions proceed in terms of whatis normal, ordinary. Because the worldis not a cluster of conjurer’s tricks, conjurers can exist” (p. 21).

Thetheory-ladenness of perception thus by no means entails relativism orskepticism. For it doesn’t entail thatdisagreement between observers need be total or even massive, or that all ormost of our perceptual judgments might be in error. Indeed (and to go beyond what Hanson himselfsays), it is consistent with holding that there is some level of theory, some very general way of carving up the basicstructure of the world, that is common to all observers and which we cannotcoherently deny to be a reflection of reality.

Another keyinsight from Hanson is that the role languageplays in the theory-ladenness of observation:

There is a ‘linguistic’ factor in seeing, although there isnothing linguistic about what forms in the eye, or in the mind’s eye. Unless there were this linguistic element,nothing we ever observed could have relevance for our knowledge… For what is itfor things to make sense other than for descriptions of them to be composed ofmeaningful sentences? (p. 25)

Part of thishas to do with the general and essential connection in human beings betweenthought and language, a topic I examine in some detail at pp. 91-103 and 245-56of my book Immortal Souls. Our being rational animals – that is to say,animals capable of grasping concepts, putting them together into propositions,and reasoning logically from one proposition to another – goes hand-in-handwith our having a language with the semantic properties and combinatorial structurehuman languages have.

Hanson’spoint also has to do in part with the thesis that certain specific ways ofconceptualizing the world are impossible unless certain specific forms of linguisticrepresentation are first in place. Theexamples he emphasizes have to do with how the formation of certain concepts inphysics was possible only after certain mathematical techniques had beendeveloped. (I had occasion to discuss inapost from a few years ago the way the invention of novel systems of symbolsmakes possible new ways of conceptualizing things.)

In anyevent, it is crucial to emphasize that here too we are not talking about somethingentirely separable from and tacked on to perceptual experience. Rather, having a linguistically expressible contentis something inherent to distinctivelyhuman perceptual experience, at least in a mature and normal human being. In human experience, conceptual and sensorycontent are fused, two aspects of onething rather than an aggregate of a purely intellectual state (as in anangel) and a purely sentient state (as in a non-human animal).

It mayilluminate things to consider the Thomistic view that as a rational animal, ahuman being has a single soul that grounds both his intellectual and sensorypowers, rather than distinct rational and sensory souls. As Aquinas says in Disputed Questions on the Soul, “the sentient soul in man is noblerthan that in other animals, because in man it is not only sentient but alsorational” and again, “the sentient soul in man is not a non-rational soul butis at once a sentient and rational soul” (Article XI, at p. 147 of the Rowan translation). If this were not so, then (the Thomistargues) a human being would not be a single substance, but a mash-up of twosubstances (as human beings are on Descartes’ account).

It is oneorganism, the human being as a whole, who sees something as an ice cube (thereby conceptualizing in the act of seeing) orsees that the earth is moving (therebyhaving an experience with a propositional content expressible in asentence). And it is in one act thatthese “seeings” are accomplished, rather than in two coordinated acts. That is perfectly consistent with the obviousfact that we can distinguish between the conceptual and sensory aspects of the one act. As Hanson writes:

‘Seeing as’ and ‘seeing that’ are not components of seeing, asrods and bearings are parts of motors: seeing is not composite. Still, one canask logical questions. What must have occurred, for instance, for usto describe a man as having found a collar stud, or as having seen a bacillus? Unless he had had a visual sensation and knew what a bacillus was(and looked like) we would not say that he had seen a bacillus, except in thesense in which an infant could see a bacillus. ‘Seeing as’ and ‘seeing that’, then, are not psychological components ofseeing. They are logicallydistinguishable elements in seeing-talk, in our concept of seeing. (p. 21)

As theThomist would argue, we can distinguish between a man’s animality and hisrationality, but it doesn’t follow that his animality and rationality aregrounded in two distinct substances only contingently united. Similarly, we can distinguish between thesensory and conceptual content of a man’s seeingan ice cube or of his seeing that theearth moves. But it doesn’t followthat there are two acts here, an act of seeing and a distinct, additional actof conceptualizing or interpreting what he is seeing.

August 6, 2025

Newman on capital punishment

It wasannounced last week that Pope Leo XIV will be declaring St. John Henry Newmanto be a Doctor of the Church. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes,the Church proclaims someone to be a Doctor on account of “eminent learning”and “a high degree of sanctity.” Thiscombination makes a Doctor an exemplary guide to matters of faith andmorals. To be sure, the Doctors are notinfallible. Their authority is not as greatas that of scripture, the consensus of the Church Fathers, or the definitivestatements of the Church’s magisterium. All the same, their authority is considerable. As Aquinas notes, appeal to the authority ofthe Doctors of the Church is “one that may properly be used” in addressingdoctrinal questions, even if such an appeal by itself yields “probable”conclusions rather than incontrovertible ones (Summa Theologiae I.1.8).

It wasannounced last week that Pope Leo XIV will be declaring St. John Henry Newmanto be a Doctor of the Church. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes,the Church proclaims someone to be a Doctor on account of “eminent learning”and “a high degree of sanctity.” Thiscombination makes a Doctor an exemplary guide to matters of faith andmorals. To be sure, the Doctors are notinfallible. Their authority is not as greatas that of scripture, the consensus of the Church Fathers, or the definitivestatements of the Church’s magisterium. All the same, their authority is considerable. As Aquinas notes, appeal to the authority ofthe Doctors of the Church is “one that may properly be used” in addressingdoctrinal questions, even if such an appeal by itself yields “probable”conclusions rather than incontrovertible ones (Summa Theologiae I.1.8).Indeed,though the Doctors of the Church are not individually infallible, it would beabsurd to suppose that they could allbe wrong on some theological issue about which they are in agreement. For given their high degree of sanctity, howcould all of them be wrong about somematter of Christian morality? Given theireminence in learning, how could allof them fall into error on some point of doctrine or scriptural interpretation? Given that they are formally recognizedby the Church as exemplary guides to faith and morals, how could they all collectively lead the faithful intograve moral or theological error?

Consistencywith the consensus of the Doctors has, accordingly, been regarded by the Churchas a mark of orthodoxy in doctrine. Forexample, in 1312 the Council of Vienne defended a point of doctrine byappealing to “the common opinion ofapostolic reflection of the Holy Fathers andthe Doctors” (Denzinger section 480). Also relevant is Tuas Libenter,in which Pope Pius IX stated:

[T]hat subjection which is to be manifested by an act ofdivine faith… would not have to be limited to those matters which have beendefined by express decrees of the ecumenical Councils, or of the Roman Pontiffsand of this See, but would have to be extended also to those matters which arehanded down as divinely revealed by the ordinary teaching power of the wholeChurch spread throughout the world, andtherefore, by universal and common consent are held by Catholic theologians tobelong to faith…

[I]t is not sufficient for learned Catholics to accept andrevere the aforesaid dogmas of the Church, but… it is also necessary to subject themselves… to those forms of doctrinewhich are held by the common and constantconsent of Catholics as theological truths and conclusions, so certain thatopinions opposed to these same forms of doctrine, although they cannot becalled heretical, nevertheless deserve some theological censure. (Denzingersections 1683-1684, emphasis added)

Here Pius IXheld the consensus opinion of Catholic theologians to have such a high statusthat even if opposed views are not strictly heretical, they nevertheless “deservesome theological censure.” Now, theDoctors of the Church are the theologians on whom the Church has placed aspecial stamp of approval, putting them forward as models. It stands to reason that if there is aconsensus among them on some thesisof faith or morals, that is powerful evidence that it must be correct.

Now,consider the topic of capital punishment. Even if we just confined ourselves to scripture, or to the consensus ofthe Fathers of the Church, or to the consistent teaching of the popes down toBenedict XVI, there can be no question whatsoever that the Church has taughtirreformably that capital punishment can be licit in principle. That is not to deny that some of the Fathersand some of these popes have recommended against using it in practice, but the point is that even theyacknowledged that it is not intrinsicallywrong to inflict the death penalty. Joseph Bessette and I demonstrate this at length in our book By Man Shall His Blood Be Shed: A CatholicDefense of Capital Punishment. I have also done so elsewhere, such as in my Catholic World Report article “CapitalPunishment and the Infallibility of the Ordinary Magisterium.”

All thesame, it is useful to consider what the Doctors of the Church have said on thematter, because they too are in agreement that the death penalty can inprinciple be a legitimate punishment. This would be a powerful argument for the liceity of capital punishmenteven if we didn’t already have scripture, the Fathers, and two millennia ofpapal teaching. Adding the Doctors tothe witnesses on this matter puts icing on the cake, as it were, highlightingthe futility of thinking that this is a teaching the Church could reverse. The Doctors who have addressed the topic ofcapital punishment include St. Ephraem, St. Hilary, St. Gregory of Nazianzus,St. Ambrose, St. Jerome, St. John Chrysostom, St. Augustine, St. Bernard ofClairvaux, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Peter Canisius, St. Robert Bellarmine, andSt. Alphonsus Liguori. (The earliest ofthese thinkers are, of course, Fathers as well.) All of them agree that it can be morallylegitimate in principle, even those among them who recommend against using itin practice. (See the book and articlereferred to above for the details.)

We can nowadd St. John Henry Newman to this consensus. The death penalty was not a topic Newman said a great deal about, butwhat he did say is important. Forexample, in Lecture 8of Lectures on the Present Position ofCatholics in England, Newman cites the following example of the way apractice can be embodied in the tradition of a nation like England rather than inexplicit law: “There is no explicit written law, for instance, simply declaringmurder to be a capital offence, unless, indeed, we have recourse to the divinecommand in the ninth chapter of the book of Genesis.” (This statement is from a longer passagefirst written when Newman was a Protestant, which he quotes in order to commenton it. As he immediately goes on to sayabout the passage, “I see nothing to alter in these remarks, written many yearsbefore I became a Catholic.”)

Newman’sreference here is to Genesis 9:5-6, which states:

For your lifeblood I will surely require a reckoning; ofevery beast I will require it and of man; of every man’s brother I will requirethe life of man. Whoever sheds the bloodof man, by man shall his blood be shed; for God made man in his own image.

Newmanunderstands this passage to be an “explicit written law… declaring murder to bea capital offence,” and one that holds of “divine command.” Note that this is diametrically opposed to modernattempts to reinterpret this passage as merely a divine prediction that murderwould as a matter of fact lead toretaliation. For Newman, God is notmerely predicting but indeed commanding that murderers should beslain, and as a matter of punishment. And here he is, of course, simply reiteratingwhat the traditional understanding always said.

In a seriesof letters to his nephew, Newman addressed questions about whetherthe Church has behaved in an immoral way over the centuries. Among the points he makes are that one mustdistinguish between, on the one hand, the state’s having the power justly topunish offenders with death, and on the other hand, specific cases where thispower was used in a cruel manner. Hewrites:

It is on the Inquisition that you mainly dwell; the questionis whether such enormity of cruelty, as is commonly ascribed to it, is to beconsidered the act of the Church. As toDr. Ward in the Dublin Review, hispoint (I think) was not the question of cruelty,but whether persecution, such as in Spain, was unjust; and with the capital punishment prescribed in the Mosaiclaw for idolatry, blasphemy, and witchcraft, and St. Paul's transferring thepower of the sword to Christian magistrates, it seems difficult to callpersecution (commonly so called) unjust. I suppose in like manner he would notdeny, but condemn, the craft and cruelty, and the wholesale character ofSt. Bartholomew's Massacre; but still would argue in the abstract in defence ofthe magistrate's bearing the sword, and of the Church's sanctioning its use, inthe aspect of justice, as Moses, Joshua, and Samuel might use it, againstheretics, rebels, and cruel and crafty enemies.

Note firstthat Newman says that capital punishment is “prescribed” in the Mosaic law forvarious offenses, and that such killing is to be understood “in the aspect ofjustice.” This should, of course, be obviousenough to anyone who reads the first five books of the Old Testament, butoccasionally people will suggest that the Old Testament merely permits the death penalty withoutactually commending it. Clearly, Newmanwould have no truck with such sophistry.

The secondthing to note is Newman’s allusion here to Romans 13: 3-4, which says:

For rulers are not a terror to good conduct, but to bad. Would you have no fear of him who is inauthority? Then do what is good, and youwill receive his approval, for he is God’s servant for your good. But if you do wrong, be afraid, for he doesnot bear the sword in vain; he is the servant of God to execute his wrath onthe wrongdoer.

This hastraditionally been understood as sanctioning capital punishment, and Newmanclearly has this interpretation in mind when he refers to “St. Paul'stransferring the power of the sword” and “the magistrate's bearing the sword,and of the Church's sanctioning its use.” With this passage too, death penalty opponents sometimes proposestrained reinterpretations, but Newman would not agree with them.

But there ismore to be said. For note that Newmanrefers, specifically, to “St. Paul's transferring the power of the sword to Christian magistrates.” This too is part of the traditionalunderstanding, and yet another thing that modern day abolitionists sometimesresist. For it is sometimes proposedthat, even if the death penalty is licit as a matter of natural law, its use isnot compatible with the higher demands of specifically Christian morality. Newman would clearly reject this claim aswell. Again, he holds that St. Paul’steaching authorizes the use of capital punishment for Christian rulers in particular, not merely for states governedonly by natural law.

In short, wenow have the testimony of yet another Doctor of the Church that the liceity ofthe death penalty is the teaching of Genesis 9 and Romans 13, and that thisteaching is a matter of Christian morality no less than of natural law. This directly contradicts those who claimthat the Church could teach that capital punishment is intrinsically wrong, orthat scripture merely tolerates rather than sanctions it, or that it iscontrary to the higher demands of the Gospel even if it is consistent withnatural law.

Now, Newmanis best known for his theology of the development of doctrine. Could claims like the ones we’ve just seenhim reject nevertheless be justified by Newman’s own criteria as “developments”of Church teaching on the death penalty? Clearly not, because Newman, like St. Vincent of Lerins (the other greattheologian of doctrinal development), insists that a genuine development cannever contradict past teaching. Newman writes:

A true development [of doctrine], then, may be described asone which is conservative of the course of antecedent developments being reallythose antecedents and something besides them: it is an addition whichillustrates, not obscures, corroborates, not corrects, the body of thought fromwhich it proceeds; and this is its characteristic as contrasted with acorruption… A developed doctrine which reverses the course of development whichhas preceded it, is no true development but a corruption. (AnEssay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, Chapter 5)

Suppose yousay “All men are mortal, and Socrates is a man.” If I add “So, Socrates is mortal,” I havesaid something that can be said to be a developmentof what you said, because it follows logically from what you said. It addssomething, insofar as it says something you did not yourself say. But nevertheless, what it adds was alreadyimplicitly there in what you said, and I have simply drawn it out.

By contrast,if I added something like “So, all men are redheads,” I could not be said to have developed what yousaid, because my addition in no way follows from what you said, and indeed hasnothing at all to do with what you said. Even more obviously, if I added either “Some men are immortal” or“Socrates is immortal,” I would not only not have “developed” what you said,but, on the contrary, I would have reversedand contradicted what you said. Forthe claim that “Some men are immortal” directly contradicts your statement that“All men are mortal.” And the statement“Socrates is immortal,” though it does not explicitly contradict what you said,does contradict what was implicit inyour remarks.

Similarly,to say that the death penalty is intrinsically wrong, or that it is notsanctioned by scripture, or that it is never permitted by the higher standardsof Christian morality, would contradictand reverse what scripture and tradition have consistently said. Hence to teach such things would, by Newman’scriteria, not count as a development of doctrine, but rather as what he calls a“corruption” of doctrine that attempts to “correct” rather than corroborate it,and which “obscures” rather than illuminates it.

Newman,then, gives no aid and comfort whatsoever to Catholics who would like adoctrinal reversal on this matter. Onthe contrary, his words clearly condemn them.

July 30, 2025

Suffering for the truth (Updated)

As manyreaders will have heard by now, last week Detroit’s new archbishop Edward Weisenburgersuddenlyfired three well-known professors at Sacred Heart Major Seminary:theologians Ralph Martin and Eduardo Echeverria and canon lawyer EdwardPeters. No official explanation has beengiven. Martin has said that he was told onlyand vaguely that it had to do with “concerns about [his] theologicalperspectives.” Echeverria has declined commentbecause of a non-disclosure agreement. Peters says that he has “retained counsel.”

As manyreaders will have heard by now, last week Detroit’s new archbishop Edward Weisenburgersuddenlyfired three well-known professors at Sacred Heart Major Seminary:theologians Ralph Martin and Eduardo Echeverria and canon lawyer EdwardPeters. No official explanation has beengiven. Martin has said that he was told onlyand vaguely that it had to do with “concerns about [his] theologicalperspectives.” Echeverria has declined commentbecause of a non-disclosure agreement. Peters says that he has “retained counsel.”I have beencommenting on the matter at Twitter/X and, because of its importance, thoughtit appropriate to do so here as well. One thing all three of these professors are known for is their longstandingdefense of the Magisterium and traditional teaching of the Church. They have in recent years also respectfullycriticized Pope Francis, because of words and actions of the pope that generatedcontroversy due to their apparent conflict with the Church’s traditional teaching(on matters such as Holy Communion for those in adulterous unions, the deathpenalty, non-Christian religions, and blessings for homosexual couples).

In doing so,they were perfectly within their rights as theologians and as Catholics. As Ihave documented elsewhere, the Church has always acknowledged that therecan be cases where it is legitimate for the faithful with the relevanttheological expertise respectfully to raise criticisms of problematicmagisterial statements, even publicly. TheChurch addressed the matter in some detail during the pontificate of St. JohnPaul II, in the instruction DonumVeritatis. Martin, Echeverria,and Peters all have the relevant expertise and have presented their objectionswith respect to the person and office of the pope. They have no history as “rad trad” firebrandsor the like but are men of proven learning and sobriety. A reasonable person might disagree with them,but could not accuse them of violating the theological and canonical normsgoverning theological discussion in the Church.

All thesame, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that they were fired because oftheir theological views. Again, Martin,at least, was explicitly told that his firing had to do with that. And that theological animus was the motive ismade even more plausible by the fact that one of the first things Archbishop Weisenburgerdid upon taking office was to crackdown on traditional Latin Mass communities in the archdiocese. The archbishop has not explained how hisharsh dealings with Catholics of more traditional opinions can be reconciledwith whathe has said elsewhere about how the faithful should treat one another:

Pope Francis is calling us to be a truly listening church...It is perhaps helpful also to note what synodality is not. It is not a political process in which thereare winners and losers. We must notthink of synodality as a power game whereby those with differing theologicalvisions of the church and its mission contend for control and dominance…Dialogue and communication are essential for bishops to exercise theirservant-leadership role on behalf of God’s people.

Nor, despitehis admiration for Pope Francis, has the archbishop explained how his actionscan be squared with what DDF prefect Cardinal Victor Manuel Fernández tellsus was the late pope’s desire “instead of persecutions and condemnations,to create spaces for dialogue” and to avoid “all forms of authoritarianism thatseek to impose an ideological register.”

Otheradmirers of Pope Francis well-known for their endless chatter about dialogue, inclusion,and mercy have reacted with merciless glee at the peremptory exclusion of Martin,Echeverria, and Peters – and in some cases thrown in gratuitous smears to boot. Austen Ivereigh matter-of-factly characterizes themas “notoriously... intemperate.” It isdifficult to judge this to be anything but a brazen lie, which Ivereigh perhapsthinks he can get away with because few of his readers are likely to know muchabout the three professors. But whetheror not he knows it to be false, the reality is precisely the opposite of whathe says. Echeverria long defended PopeFrancis before only reluctantly and cautiously changing his mind, Peters iswell-known for lawyerly nuance, and Martin is about as mild-mannered as can beimagined.

Mike Lewis accusesthe three professors of “heresy.” Thisis a preposterous calumny. As the Catechismdefines it, “heresy is the obstinatepost-baptismal denial of some truth which must be believed with divine andcatholic faith, or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same”(2089). Never have any of the threeprofessors expressed any denial or doubt about any such doctrine. Michael Sean Winters is especially shamelessin his bad faith, applauding the firing of Martin, Echeverria, and Peters whilein the same breath defending Fr. Charles Curran’s notorious dissent fromthe Church’s teaching on sexual morality.

It should berecalled that last week’s firings are not the first time prominent and loyalCatholic academics lost their positions because they criticized Pope Francisfor failing to uphold traditional teaching. For example, in 2017, after criticizing the pope for sowing doctrinalconfusion, Fr. Thomas Weinandy wasremoved from his position as consultant to the U.S. bishops’ Committee onDoctrine. After signing a letter thataccused Pope Francis of heresy in 2019, philosopher John Rist wasbanned from all pontifical universities, and theologian Fr. Aidan Nichols has had difficulty finding a stable academicposition.

It isimportant to emphasize that, like the three professors fired last week, theseare not mere media influencers, “rad trad” hotheads, or otherwise marginal figures. They are eminent academics long known for theirdeep learning, scholarly rigor and nuance, and fidelity to the teaching andMagisterium of the Church. Nor were theycritical of Francis from the start, but only after his problematic statementsand actions accumulated. One candisagree with some of the things they have said (for example, I think Rist andNichols went too far, asI said at the time), while acknowledging that their arguments are serious,presented in good faith, and worthy of respectful engagement.

And itshould be noted too that these men are only a handful from among a much largerbody of eminent scholars known for their longtime loyalty to the Church and itsMagisterium who were deeply troubled by aspects of Pope Francis’s pontificate –Germain Grisez, John Finnis, Josef Seifert, Msgr. Nicola Bux, Cardinal RaymondBurke, Cardinal Gerhard Müller, Cardinal George Pell, and on and on and on. Even if we confined ourselves just toacademics and other Catholic thinkers and churchmen who have been publiclyrespectfully critical of Pope Francis, the list would be very long. If we added those who have opted for variousreasons to keep their concerns private, it would be extremely long.

The reasonis not that these people, long known for their deep loyalty to the Church andto other recent popes, somehow magically all became heretics or dissenters underFrancis. The reason is that Pope Franciswas simply unlike any previous pope in history in thenumber of his theologically problematic statements and actions. None of the previous popes notorious for suchwords and actions – not Liberius, not Honorius, not John XXII – comes close. It is impossible for a theologicallywell-informed and intellectually honest person not to see the problem, and thegravity of the problem.

Yet for themost part, Pope Francis’s defenders have not seriously engaged with thesethinkers’ arguments, and none of Francis’s defenders is remotely as notable fortheological expertise and sobriety as the most eminent of the pope’s critics. Instead, for the most part Martin, Echeverria,and Peters, like Weinandy, Nichols, and Rist before them, have been subject tovulgar abuse and dismissiveness from their moral and intellectual inferiors –adding insult to the grave injury of having their livelihoods unjustly takenfrom them.

Again, Donum Veritatis taught that it ispossible for there to be cases in which Catholics with the relevant theologicalexpertise can legitimately raise criticisms of defective statements from theChurch’s magisterial authorities. Indeed,the instruction even acknowledges that “such a situation can certainly prove adifficult trial. It can be a call tosuffer for the truth, in silence and prayer, but with the certainty, that ifthe truth really is at stake, it will ultimately prevail.”

The scholarswho have lost their positions for criticizing Pope Francis’s errors are nowindeed suffering for the truth. But thetruth will ultimately prevail, as it did in the cases of Liberius, Honorius,and John XXII. We do not know how longthis will take. In the case of JohnXXII, it happened very quickly; in the case of Honorius, it took decades. But we can have good hope that Pope Leo XIV,who seems to be a kind and generous man who appreciates theological learningand wants to unify the Church, will approach these controversies in a lessdivisive and draconian manner than did his predecessor.

UPDATE 8/2: The Pillar reportsthat Sacred Heart Major Seminary’s policy for terminating faculty requires “dueprocess,” “specifying the grounds for dismissal,” and other conditions. If these and the other details about the case that have been reported are accurate, it would seem that the firings violated the seminary's own policy.

Suffering for the truth

As manyreaders will have heard by now, last week Detroit’s new archbishop Edward Weisenburgersuddenlyfired three well-known professors at Sacred Heart Major Seminary:theologians Ralph Martin and Eduardo Echeverria and canon lawyer EdwardPeters. No official explanation has beengiven. Martin has said that he was told onlyand vaguely that it had to do with “concerns about [his] theologicalperspectives.” Echeverria has declined commentbecause of a non-disclosure agreement. Peters says that he has “retained counsel.”

As manyreaders will have heard by now, last week Detroit’s new archbishop Edward Weisenburgersuddenlyfired three well-known professors at Sacred Heart Major Seminary:theologians Ralph Martin and Eduardo Echeverria and canon lawyer EdwardPeters. No official explanation has beengiven. Martin has said that he was told onlyand vaguely that it had to do with “concerns about [his] theologicalperspectives.” Echeverria has declined commentbecause of a non-disclosure agreement. Peters says that he has “retained counsel.”I have beencommenting on the matter at Twitter/X and, because of its importance, thoughtit appropriate to do so here as well. One thing all three of these professors are known for is their longstandingdefense of the Magisterium and traditional teaching of the Church. They have in recent years also respectfullycriticized Pope Francis, because of words and actions of the pope that generatedcontroversy due to their apparent conflict with the Church’s traditional teaching(on matters such as Holy Communion for those in adulterous unions, the deathpenalty, non-Christian religions, and blessings for homosexual couples).

In doing so,they were perfectly within their rights as theologians and as Catholics. As Ihave documented elsewhere, the Church has always acknowledged that therecan be cases where it is legitimate for the faithful with the relevanttheological expertise respectfully to raise criticisms of problematicmagisterial statements, even publicly. TheChurch addressed the matter in some detail during the pontificate of St. JohnPaul II, in the instruction DonumVeritatis. Martin, Echeverria,and Peters all have the relevant expertise and have presented their objectionswith respect to the person and office of the pope. They have no history as “rad trad” firebrandsor the like but are men of proven learning and sobriety. A reasonable person might disagree with them,but could not accuse them of violating the theological and canonical normsgoverning theological discussion in the Church.

All thesame, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that they were fired because oftheir theological views. Again, Martin,at least, was explicitly told that his firing had to do with that. And that theological animus was the motive ismade even more plausible by the fact that one of the first things Archbishop Weisenburgerdid upon taking office was to crackdown on traditional Latin Mass communities in the archdiocese. The archbishop has not explained how hisharsh dealings with Catholics of more traditional opinions can be reconciledwith whathe has said elsewhere about how the faithful should treat one another:

Pope Francis is calling us to be a truly listening church...It is perhaps helpful also to note what synodality is not. It is not a political process in which thereare winners and losers. We must notthink of synodality as a power game whereby those with differing theologicalvisions of the church and its mission contend for control and dominance…Dialogue and communication are essential for bishops to exercise theirservant-leadership role on behalf of God’s people.

Nor, despitehis admiration for Pope Francis, has the archbishop explained how his actionscan be squared with what DDF prefect Cardinal Victor Manuel Fernández tellsus was the late pope’s desire “instead of persecutions and condemnations,to create spaces for dialogue” and to avoid “all forms of authoritarianism thatseek to impose an ideological register.”

Otheradmirers of Pope Francis well-known for their endless chatter about dialogue, inclusion,and mercy have reacted with merciless glee at the peremptory exclusion of Martin,Echeverria, and Peters – and in some cases thrown in gratuitous smears to boot. Austen Ivereigh matter-of-factly characterizes themas “notoriously... intemperate.” It isdifficult to judge this to be anything but a brazen lie, which Ivereigh perhapsthinks he can get away with because few of his readers are likely to know muchabout the three professors. But whetheror not he knows it to be false, the reality is precisely the opposite of whathe says. Echeverria long defended PopeFrancis before only reluctantly and cautiously changing his mind, Peters iswell-known for lawyerly nuance, and Martin is about as mild-mannered as can beimagined.

Mike Lewis accusesthe three professors of “heresy.” Thisis a preposterous calumny. As the Catechismdefines it, “heresy is the obstinatepost-baptismal denial of some truth which must be believed with divine andcatholic faith, or it is likewise an obstinate doubt concerning the same”(2089). Never have any of the threeprofessors expressed any denial or doubt about any such doctrine. Michael Sean Winters is especially shamelessin his bad faith, applauding the firing of Martin, Echeverria, and Peters whilein the same breath defending Fr. Charles Curran’s notorious dissent fromthe Church’s teaching on sexual morality.

It should berecalled that last week’s firings are not the first time prominent and loyalCatholic academics lost their positions because they criticized Pope Francisfor failing to uphold traditional teaching. For example, in 2017, after criticizing the pope for sowing doctrinalconfusion, Fr. Thomas Weinandy wasremoved from his position as consultant to the U.S. bishops’ Committee onDoctrine. After signing a letter thataccused Pope Francis of heresy in 2019, philosopher John Rist wasbanned from all pontifical universities, and theologian Fr. Aidan Nichols has had difficulty finding a stable academicposition.

It isimportant to emphasize that, like the three professors fired last week, theseare not mere media influencers, “rad trad” hotheads, or otherwise marginal figures. They are eminent academics long known for theirdeep learning, scholarly rigor and nuance, and fidelity to the teaching andMagisterium of the Church. Nor were theycritical of Francis from the start, but only after his problematic statementsand actions accumulated. One candisagree with some of the things they have said (for example, I think Rist andNichols went too far, asI said at the time), while acknowledging that their arguments are serious,presented in good faith, and worthy of respectful engagement.

And itshould be noted too that these men are only a handful from among a much largerbody of eminent scholars known for their longtime loyalty to the Church and itsMagisterium who were deeply troubled by aspects of Pope Francis’s pontificate –Germain Grisez, John Finnis, Josef Seifert, Msgr. Nicola Bux, Cardinal RaymondBurke, Cardinal Gerhard Müller, Cardinal George Pell, and on and on and on. Even if we confined ourselves just toacademics and other Catholic thinkers and churchmen who have been publiclyrespectfully critical of Pope Francis, the list would be very long. If we added those who have opted for variousreasons to keep their concerns private, it would be extremely long.

The reasonis not that these people, long known for their deep loyalty to the Church andto other recent popes, somehow magically all became heretics or dissenters underFrancis. The reason is that Pope Franciswas simply unlike any previous pope in history in thenumber of his theologically problematic statements and actions. None of the previous popes notorious for suchwords and actions – not Liberius, not Honorius, not John XXII – comes close. It is impossible for a theologicallywell-informed and intellectually honest person not to see the problem, and thegravity of the problem.

Yet for themost part, Pope Francis’s defenders have not seriously engaged with thesethinkers’ arguments, and none of Francis’s defenders is remotely as notable fortheological expertise and sobriety as the most eminent of the pope’s critics. Instead, for the most part Martin, Echeverria,and Peters, like Weinandy, Nichols, and Rist before them, have been subject tovulgar abuse and dismissiveness from their moral and intellectual inferiors –adding insult to the grave injury of having their livelihoods unjustly takenfrom them.

Again, Donum Veritatis taught that it ispossible for there to be cases in which Catholics with the relevant theologicalexpertise can legitimately raise criticisms of defective statements from theChurch’s magisterial authorities. Indeed,the instruction even acknowledges that “such a situation can certainly prove adifficult trial. It can be a call tosuffer for the truth, in silence and prayer, but with the certainty, that ifthe truth really is at stake, it will ultimately prevail.”

The scholarswho have lost their positions for criticizing Pope Francis’s errors are nowindeed suffering for the truth. But thetruth will ultimately prevail, as it did in the cases of Liberius, Honorius,and John XXII. We do not know how longthis will take. In the case of JohnXXII, it happened very quickly; in the case of Honorius, it took decades. But we can have good hope that Pope Leo XIV,who seems to be a kind and generous man who appreciates theological learningand wants to unify the Church, will approach these controversies in a lessdivisive and draconian manner than did his predecessor.

July 24, 2025

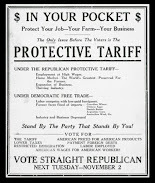

A postliberal middle ground on trade

In my latestarticle at Postliberal Order, Idefend a postliberal middle ground position on tariffs and other aspects of trade policythat avoids both the errors of classical liberalism and a rigid protectionism.

In my latestarticle at Postliberal Order, Idefend a postliberal middle ground position on tariffs and other aspects of trade policythat avoids both the errors of classical liberalism and a rigid protectionism.

July 19, 2025

Heeding Anscombe on just war doctrine

ElizabethAnscombe’s “Warand Murder” is a magnificent essay, an intellectually rigorous andmorally serious defense of traditional Christian and natural law teachingagainst pacifists on the one side and, on the other, those who attempt torationalize the unjust killing of civilians. As she argues, both errors feed off of one another. The essay is perhaps even more relevant todaythan it was at the time she wrote it.

ElizabethAnscombe’s “Warand Murder” is a magnificent essay, an intellectually rigorous andmorally serious defense of traditional Christian and natural law teachingagainst pacifists on the one side and, on the other, those who attempt torationalize the unjust killing of civilians. As she argues, both errors feed off of one another. The essay is perhaps even more relevant todaythan it was at the time she wrote it.Here is asummary of her position. The pacifistholds that all killing is immoral,even when necessary to protect citizens against criminal evildoers within anation, or foreign adversaries without. This position is contrary to the basic precondition of any social order,which is the right to protect itself against attempts to destroy it. It also has no warrant in the orthodox Christiantradition. A less extreme but relatederror is the thesis that violence can never justly be initiated, but at mostcan only ever be justified in response to those who have initiated it. In fact, Anscombe argues, what matters is notwho strikes the first blow, but who is in the right. For example, it was in her judgment right forthe British to initiate violence in order to suppress chattel slavery.

That is oneset of errors. But another and oppositeextreme error is to abuse the principle that war can sometimes be justifiable,in order to try to rationalize violence that is in fact unjust. Indeed, this opposite extreme is, inAnscombe’s view, the more common error. Andit is more common in war than in police activity, because war affords more occasionsfor the evil of killing the innocent, and civilians in particular. The principle of double effect is too oftenmisapplied in attempts to rationalize such killing.

Having givena general description of these two sorts of error, Anscombe then goes on toexamine each in more detail. Shesuggests that in the early twentieth century, some were drawn to pacifism inpart as an overreaction to universal conscription (which she regards as anevil). But her main focus is on thetheme that pacifism derives from a distortion of Christianity. In part this has to do with a hostility tothe ethos of the Old Testament, which she argues is widely misunderstood andwidely and wrongly thought to be at odds with the New Testament. But the New Testament too has been badlymisunderstood. For example, counsels towhich only some are called (such asgiving away one’s worldly goods) are sometimes misrepresented as preceptsbinding on all.

“The truthabout Christianity,” Anscombe says, “is that it is a severe and practicablereligion, not a beautifully ideal but impracticable one” (p. 48). But the distortions she describes have madeChristianity seem to be an ideal butimpracticable one. And the attractionsome Christians have for pacifism is an example. Many Christians and non-Christians alikebelieve the falsehood that Christ calls us all to pacifism. And because no society could survive if itpracticed pacifism, many thus conclude that Christian morality is simply notpractical.

Here, asAnscombe argues, is where pacifism inadvertently paves the way for those whorationalize the murder of the innocent. Falselysupposing that all violence is eviland also noting that violence is necessary to preserve a society againstevildoers, they take the short step to the conclusion that “committed to‘compromise with evil,’ one must go the whole hog and wage war à outrance” (p. 48). In other words, once we are convinced thatwe’re going to have to do evil anyway in order to protect society, there’s nolimit to the evil we will rationalize as necessary to achieve this goodend. Unrealistic moralizing has as itssequel an amoral realpolitik, falselypresenting itself as the only alternative.

WithCatholics, Anscombe says, this amorality masquerades as an application of theprinciple of double effect. True, thisprinciple can indeed in some cases justify actions that foreseeably risk harmto civilians, when that harm is not intended and when it is not out ofproportion to the good to be achieved. (For example, it can be justifiable to bomb an enemy military base evenif one foresees, while not intending, that some civilians nearby could bekilled as a result.)

The trouble,Anscombe says, is that people often play fast and loose with the notion of“intention” in order to abuse the principle of double effect. For example, it would be sheer sophistry foran employee to say that when he helped his boss embezzle from the company, his“intention” was not really to assistin embezzlement, but only to avoid getting fired, so that the action could bejustified by double effect. Similarly,Anscombe argues, it is sophistry to pretend that the obliteration bombing ofcities does not involve any intentional killing of civilians, but only theintention to end a war earlier. Anothersophistry involves interpreting what counts as a “combatant” very broadly, soas to try to justify attacks on the civilian population in general. Anscombe also responds to various other attemptsto rationalize violations of just war criteria.

That, again,is the argument in outline. Here aresome ways it is relevant today. We have,on the one hand, some Catholics who appear at least to flirt with pacifism. Pope Francis said things that implied thatwar could never be just and that traditional teaching on this matter needed tobe rethought, though healso said things that pointed in the other direction. As with other topics, his teaching on thismatter was simply muddled rather than a clear departure from tradition. But it was muddled in a way that gives aidand comfort to the first, pacifistic erroneous extreme identified by Anscombe.

On the otherhand, we also have many who go to the opposite extreme criticized by Anscombe,of trying to rationalize unjust harm to civilian populations by abuse of theprinciple of double effect and related sophistries. For example, this is the case with much ofthe commentary on Israel’s war in Gaza. Israelcertainly had the right and indeed the duty to retaliate for the diabolicalHamas attack of October 7, 2023, which killed almost 1,200 people. But many seem to think that this gives Israela blank check to do whatever it likes in Gaza, or at least whatever it likesshort of deliberately targeting civilians.

That is notthe case. Yes, traditional just war doctrineholds that it is always immoral deliberately to kill civilians. But that is by no means all that it says onthe matter. It also holds that it isimmoral deliberately to destroy civilian property and infrastructure, andthereby to make normal civilian life impossible. To be sure, it holds too that it can, by theprinciple of double effect, sometimes be permissible to carry out militaryactions that put civilian lives and property at risk, where such risk is not intended but simply foreseen. But it also holds that this harm must not be out of proportion to thegood that one hopes to secure by way of such military action.

ThroughoutGaza, however, civilian property and infrastructure have been largely destroyed,and ordinary life made impossible. The resultinghumanitarian crisis has been steadily worsening. Casualty numbers in Gaza are hotly disputed,but they are undeniably high. According toa recent report:

Almost 84,000 people died in Gaza between October 2023 andearly January 2025 as a result of the Hamas-Israel war, estimates the firstindependent survey of deaths. More thanhalf of the people killed were women aged 18-64, children or people over 65,reports the study.

Suppose for thesake of argument that the true number is half of that, or even just one thirdof that. That would still be extremelyhigh. Such loss of life, destruction ofbasic infrastructure, and making of ordinary civilian life impossible are outof proportion to the evil Israel is retaliating against. And this is putting aside the awfulconditions under which Gazans have been living for years, and the allegationsof cases where civilians have been deliberately targeted during the currentwar. These too are hotly disputedmatters, but the point is that even if wedon’t factor them in, Israeli action in Gaza seems clearly disproportionateand thus not justifiable by the principle of double effect.

There isalso the sophistry some commit of pretending that if a civilian sympathizeswith Hamas, he is morally on a par with a combatant and may be treated as such. And then there is the proposal somehave made to dispossess the Gazans altogether, which would only add a further,massive layer of injustice.

None of thiscan facilitate a long-term solution to the Israel-Palestine problem, but will inevitablygreatly inflame further already high hostility against Israel. A commitment to preserving the basic preconditionsof ordinary civilian life for Israelisand Palestinians alike is both morally required by just war criteria, and aprecondition to any workable modus vivendi.

July 11, 2025

A second Honorius?

Like hispredecessor Honorius, Pope Francis failed clearly to uphold traditionalteaching at a time the Church was sick from heresy. So I argue in my contributionto a symposium on Francis in the latest issue of

The Lamp

.

Like hispredecessor Honorius, Pope Francis failed clearly to uphold traditionalteaching at a time the Church was sick from heresy. So I argue in my contributionto a symposium on Francis in the latest issue of

The Lamp

.

July 10, 2025

Aquinas and prudential judgment

Incontemporary debates in Catholic moral theology, a distinction is often drawnbetween actions that are flatly ruled out in principle and those whosepermissibility or impermissibility is a matter of prudential judgment. For example, it is often noted that abortionis wrong always and in principle, whereas how many immigrants a country oughtto allow in and under what conditions are matters of prudential judgment. But exactly what does this mean, and how dowe tell the difference between the cases?

Incontemporary debates in Catholic moral theology, a distinction is often drawnbetween actions that are flatly ruled out in principle and those whosepermissibility or impermissibility is a matter of prudential judgment. For example, it is often noted that abortionis wrong always and in principle, whereas how many immigrants a country oughtto allow in and under what conditions are matters of prudential judgment. But exactly what does this mean, and how dowe tell the difference between the cases?It isimportant at the outset to put aside some common misunderstandings. The difference between matters of principleand matters of prudential judgment is nota difference between moral questions and merely pragmatic ones. Morality is at issue in both cases. Prudence is,after all, one of the cardinal moral virtues. One can be mistaken in one’s prudential judgments, and when one is, oneis guilty of imprudence, which is a kind of moral failure (whether or not oneis culpable for the failure).

Contrary toanother misunderstanding (which I recently had occasionto rebut), to say that something is a matter of prudential judgmentand then go on to note that reasonable people can differ in their prudentialjudgments is not to commit oneself toany kind of moral relativism. Prudentialjudgments can indeed simply be mistaken. To say that reasonable people can disagree is merely to note that aperson might have made such a judgment in good faith on the basis of theevidence available to him, even if the evidence later turns out to bemisleading or his reasoning turns out to have been flawed. He is still objectively wrong all the same. Or there may in some cases be more than onereasonable way to apply a certain objective and universal moral principle, sothat reasonable people might opt to apply it in any of these different ways.

As always,illumination can be found in St. Thomas Aquinas. In several places, he makes remarks that arerelevant to understanding the difference between straightforward matters ofprinciple and matters of prudential judgment. For example, in On Evil,Aquinas notes:

The will of a rational creature is obliged to be subject toGod, but this is achieved by affirmative and negative precepts, of which thenegative precepts oblige always and on all occasions, and the affirmativeprecepts oblige always but not on every occasion… One sins mortally whodishonors God by transgressing a negative precept or not fulfilling an affirmativeprecept on an occasion when it obliges. (Question VI, Regan translation)

Though thedistinction between matters of principle and matters of prudence is somewhatloose, it seems largely (though perhaps not always) to correspond to Aquinas’sdistinction between negative precepts, which oblige on every occasion, andaffirmative precepts, which do not. Whatthis distinction amounts to is madeclearer in some remarks St. Thomas makes when commenting on St. Paul’s Epistleto the Romans:

He lists the negative precepts, which forbid a person to doevil to his neighbor. And this for tworeasons. First, because the negativeprecepts are more universal both as to time and as to persons. As to time, because the negative preceptsoblige always and at every moment. Forthere is no time when one may steal or commit adultery. Affirmative precepts, on the other hand,oblige always but not at every moment, but at certain times and places: for aman is not obliged to honor his parents every minute of the day, but at certaintimes and places. Negative precepts aremore universal as to persons, because no man may be harmed. Second, because they are more obviouslyobserved by love of neighbor than are the affirmative. For a person who loves another, ratherrefrains from harming him than gives him benefits, which he is sometimes unableto give. (Commentary on the Letter ofSaint Paul to the Romans, Chapter 13, Lecture2)

Aquinas’sexamples hopefully make his meaning clear. Consider the negative precept “Do not commit adultery.” Because adultery is intrinsically evil, wemust never commit it, period, regardless of the circumstances. And because we therefore needn’t considercircumstances, no judgment of prudence is required in order to apply the precept to circumstances. Whatever the circumstances happen to be, wesimply refrain from committing adultery, and that’s that.

By contrast,applying the affirmative precept “Honor your father and mother” does requireattention to circumstances. To be sure,the precept never fails to be binding on us (which is what Aquinas means bysaying that it “obliges always”) but exactlywhat obeying it amounts to depends crucially on circumstances (which is whyhe says that “times and places” are relevant). For example, suppose your father commands you to bring him a bottle ofwine. Does honoring him oblige you to doso? It depends. Suppose he has had a hard day, finds itrelaxing to drink in moderation, and is infirm and has trouble walking. Then it would certainly dishonor your fatherto ignore him and make him get up and fetch the bottle himself. But suppose instead that he has a seriousdrinking problem, has already had too much wine, and will likely beat you oryour mother if he gets any drunker. Thenit would not dishonor him to refuseto bring the bottle.

As Aquinassuggests in the Romans commentary, affirmative precepts involve providingsomeone with a benefit of some kind, which one is “sometimes unable togive.” Consider the affirmative preceptto give alms. Even more obviously thanin the case of the precept to honor one’s parents, what following this preceptentails concretely is highly dependent on circumstances. Obviously one cannot always be giving alms,for even if one tried to do so, one would quickly run out of money and not onlybe unable to give any further alms, but would be in need of alms oneself. How to follow this affirmative preceptclearly requires making a judgment of prudence. How much money do I need for my own family? How much might I be able to spare for others,and how frequently? Exactly who, amongall the people who need alms, should I give to? Should I give by donating money, or instead by giving food and thelike? The answers to these questions arehighly dependent on circumstances and will vary from person to person, place toplace, and time to time.

The morecomplicated and variable the circumstances, the more difficult it can be todecide on a single correct answer and thus the greater the scope for reasonabledisagreement. The disagreement can bereasonable in either of two ways. First,what might be obligatory for one person given the details of his circumstancesmay not be obligatory for another person given the details of his own verydifferent circumstances. For example, arich man is bound to be obligated to give more in the way of alms than a poorman is. Second, disagreement can bereasonable insofar as the complexity of the situation might make it uncertainwhich course of action is best even for people in the same personal circumstances. Aquinas makes such points in the Summa Theologiae:

The practical reason… is busied with contingent matters,about which human actions are concerned: and consequently, although there isnecessity in the general principles, the more we descend to matters of detail,the more frequently we encounter defects. Accordingly then… in matters of action, truth or practical rectitude isnot the same for all, as to matters of detail, but only as to the generalprinciples: and where there is the same rectitude in matters of detail, it isnot equally known to all.