Hanson on observation

According tothe conception of scientific method traditionally associated with FrancisBacon, science ought to begin with the accumulation of observations unbiased byany theoretical preconceptions. The ideais that only such theory-neutral evidence could provide an objective basis onwhich to choose between theories. Itbecame a commonplace of twentieth-century philosophy of science that this idealof theory-neutral observation is illusory, and that in reality all observationis inescapably theory-laden (to usethe standard jargon). That is to say,even to describe what it is we observe, we cannot avoid making use oftheoretical assumptions about its nature, circumstances, and so on.

According tothe conception of scientific method traditionally associated with FrancisBacon, science ought to begin with the accumulation of observations unbiased byany theoretical preconceptions. The ideais that only such theory-neutral evidence could provide an objective basis onwhich to choose between theories. Itbecame a commonplace of twentieth-century philosophy of science that this idealof theory-neutral observation is illusory, and that in reality all observationis inescapably theory-laden (to usethe standard jargon). That is to say,even to describe what it is we observe, we cannot avoid making use oftheoretical assumptions about its nature, circumstances, and so on.NorwoodRussell Hanson’s 1958 book Patternsof Discovery is commonly cited as a classic expression of thisview. And one way Hanson repays study isthat his treatment makes it clear that theory-ladenness does not by itself haverelativistic implications, contrary to what one might suppose from simplisticaccounts of contemporary philosophy of science.

To be sure,it can at first glance seemotherwise. As Hanson emphasizes, thereis a sense in which different observers operating with different backgroundassumptions can be said to see different things. One microbiologist looking through amicroscope at what’s on a certain slide might see a cell organ, while anothersees a bit of foreign matter that resulted from the staining process. One seventeenth-century astronomer looking atthe sun at dawn sees it move through the sky, while another sees the earth moving relative to the sun. And so on.

Many wouldreply that in reality, they do seethe same thing, but simply draw different inferences from it. The assumption here is that there are two things going on, a visual experienceon the one hand, and a separate act of interpretation of that experience on theother. But this, as Hanson influentiallyargued, is an illusion. One way thisillusory assumption is sometimes spelled out is by taking two perceivers tohave the same sort of retinal image, or the same physiological state, but thenimposing different interpretations on it. The problem here, as Hanson notes, is that a visual experience is simplynot the same thing as the having of a retinal image or other physiologicalstate:

Astronomers cannot be referring to these when they say theysee the sun. If they are hypnotized,drugged, drunk or distracted they may not see the sun, even though theirretinas register its image in exactly the same way as usual. Seeing is an experience. A retinal reaction is only a physical state –a photochemical excitation. Physiologists have not always appreciated the differences betweenexperiences and physical states. People,not their eyes, see. Cameras, andeye-balls, are blind. Attempts to locatewithin the organs of sight (or within the neurological reticulum behind theeyes) some nameable called ‘seeing’ may be dismissed… there is more to seeingthan meets the eyeball. (pp. 6-7)

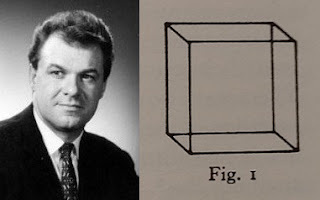

Another waythe mistaken assumption in question is often spelled out is in terms of “sense-data.” The idea here is that the two observers havesimilar sense-data – describable, say, as their being “both aware of abrilliant yellow-white disc in a blue expanse over a green one” (p. 7) – andthat they then assign different interpretations to these sense-data. But this is simply not a correct descriptionof how visual experience goes in the normal case. Consider the famous Necker cube example (Fig.1 in the image above). If shown such animage and asked what he sees, a perceiver might simply say “That’s an icecube,” or “That’s an aquarium,” or “That’s a wire frame,” or any number ofother things. Context will likely play alarge role in determining his answer. For example, if the cube is part of a larger image that looks like a Scotchglass, he’s obviously more likely to describe it as an ice cube than as anaquarium. The point though, is thatthere are clearly cases in which the way he’d describe his experience is as“seeing an ice cube” – as opposed, say, to “seeing a set of lines, and thengoing on to interpret it as an ice cube.”

Of course,there can be cases in which theperceiver says the latter rather than the former. In thosecases there are two things going on, the experience and then a separateinterpretation of it. But there are not two things going in the ordinarycase. There’s just the one thing goingon, seeing an ice cube. Similarly, inthe case of the two astronomers, one of them might describe his perceptualexperience as “seeing the sun move” and the other as “seeing the earth move,”and with each of them there is just the one thing going on rather than anexperience together with a separate act of interpreting it.

Of course,the first astronomer would (as we now know) in this case be mistaken about what he sees. But that is irrelevant to the point, which isthat the content of his experience iscorrectly captured in the description “seeing the sun move,” rather than thedescription “seeing a yellow-white disc in a blue expanse” etc. Here too we can certainly imagine eccentriccases in which what a perceiver sees could accurately be described in that oddway – for example, if the perceiver had no idea of what the sun is. But obviously that is not what is going onwith a normal adult, let alone an astronomer. And if some astronomer did “react to his visual environment with purelysense-datum responses – as does the infant or the idiot – we would think himout of his mind. We would think him not to be seeing what is around him” (p.22).

Then thereis the fact that, even when we are dealingwith oddball cases like this, they still involve the application of concepts within the perceptual experience itselfrather than in some separate act of interpretation. We characterize the experience in terms of “ayellow-white disc” rather than “the sun,” but the characterization is internalto the experience rather than tacked on to it. As Hanson writes:

The knowledge is there in the seeing and not an adjunct ofit. (The pattern of threads is there inthe cloth and not tacked on to it by ancillary operations.) We rarely catch ourselves tacking knowledgeon to what meets the eye. (p. 22)

Moreover, ifperceptual experiences did notincorporate such knowledge, we would not be able to do with them the things wedo in fact do, and which science and common sense alike require us to be ableto do with them – namely, draw inferences from them and otherwise relate themto our larger body of background knowledge, including the scientific theorieswe test by way of perceptual experience. To quote Hanson again:

Significance, relevance – these notions depend on what wealready know. Objects, events, pictures,are not intrinsically significant or relevant. If seeing were just an optical-chemical process, then nothing we sawwould ever be relevant to what we know, and nothing known could havesignificance for what we see. Visuallife would be unintelligible; intellectual life would lack a visualaspect. Man would be a blind computerharnessed to a brainless photoplate. (p. 26)

This sort ofobservation is, of course, a longstanding part of modern critiques of naïveempiricism, from Kant’s dictum that “percepts without concepts are blind” toWilfrid Sellars’ attack on “the myth of the given.” And again, at first glance it might seem toentail a kind of relativism. If what we perceivealways reflects what we know (or take ourselves to know, anyway), but differentperceivers have different bodies of knowledge (or of what they take to beknowledge), how can they ever perceive the same things?

But Hansonalso makes it clear why such a relativistic conclusion does not follow. To say that there is a sense in whichdifferent observers may see different things – as in the examples involving theobject under the microscope, the sun at dawn, or the Necker cube – does notentail that there is not also a sensein which they see the samething. Suppose two people are looking atthe cube and one says “That’s an ice cube!” whereas the other says “That’s anaquarium!” It’s not as if there is nothing about which they agree. We can imagine the conversation continuing:“Do you at least agree that there are lines there?” “Of course!” Here too what they take themselves to know is intrinsic to theexperience rather than being tacked on in a separate act ofinterpretation. But in this case it is shared knowledge.

As Hansonwrites, “if seeing different things involves having different knowledge andtheories about x, then perhaps thesense in which they see the same thing involves their sharing knowledge andtheories about x” (p. 18). Disagreement takes place against a deeperlevel of agreement. Indeed, unless therewere some level of agreement (atleast concerning what exactly the disputeis about) there couldn’t be a disagreement in the first place. As Donald Davidson would later argue, even tomake sense of what another person is saying as language (whatever he issaying in that language), we need to be able to tie his utterances to aspectsof a shared environment, which entails shared beliefs about thatenvironment. Anticipating sucharguments, Hanson notes that error is the exception rather than the rule: “Wemay be wrong, but not always – not even usually. Besides, deceptions proceed in terms of whatis normal, ordinary. Because the worldis not a cluster of conjurer’s tricks, conjurers can exist” (p. 21).

Thetheory-ladenness of perception thus by no means entails relativism orskepticism. For it doesn’t entail thatdisagreement between observers need be total or even massive, or that all ormost of our perceptual judgments might be in error. Indeed (and to go beyond what Hanson himselfsays), it is consistent with holding that there is some level of theory, some very general way of carving up the basicstructure of the world, that is common to all observers and which we cannotcoherently deny to be a reflection of reality.

Another keyinsight from Hanson is that the role languageplays in the theory-ladenness of observation:

There is a ‘linguistic’ factor in seeing, although there isnothing linguistic about what forms in the eye, or in the mind’s eye. Unless there were this linguistic element,nothing we ever observed could have relevance for our knowledge… For what is itfor things to make sense other than for descriptions of them to be composed ofmeaningful sentences? (p. 25)

Part of thishas to do with the general and essential connection in human beings betweenthought and language, a topic I examine in some detail at pp. 91-103 and 245-56of my book Immortal Souls. Our being rational animals – that is to say,animals capable of grasping concepts, putting them together into propositions,and reasoning logically from one proposition to another – goes hand-in-handwith our having a language with the semantic properties and combinatorial structurehuman languages have.

Hanson’spoint also has to do in part with the thesis that certain specific ways ofconceptualizing the world are impossible unless certain specific forms of linguisticrepresentation are first in place. Theexamples he emphasizes have to do with how the formation of certain concepts inphysics was possible only after certain mathematical techniques had beendeveloped. (I had occasion to discuss inapost from a few years ago the way the invention of novel systems of symbolsmakes possible new ways of conceptualizing things.)

In anyevent, it is crucial to emphasize that here too we are not talking about somethingentirely separable from and tacked on to perceptual experience. Rather, having a linguistically expressible contentis something inherent to distinctivelyhuman perceptual experience, at least in a mature and normal human being. In human experience, conceptual and sensorycontent are fused, two aspects of onething rather than an aggregate of a purely intellectual state (as in anangel) and a purely sentient state (as in a non-human animal).

It mayilluminate things to consider the Thomistic view that as a rational animal, ahuman being has a single soul that grounds both his intellectual and sensorypowers, rather than distinct rational and sensory souls. As Aquinas says in Disputed Questions on the Soul, “the sentient soul in man is noblerthan that in other animals, because in man it is not only sentient but alsorational” and again, “the sentient soul in man is not a non-rational soul butis at once a sentient and rational soul” (Article XI, at p. 147 of the Rowan translation). If this were not so, then (the Thomistargues) a human being would not be a single substance, but a mash-up of twosubstances (as human beings are on Descartes’ account).

It is oneorganism, the human being as a whole, who sees something as an ice cube (thereby conceptualizing in the act of seeing) orsees that the earth is moving (therebyhaving an experience with a propositional content expressible in asentence). And it is in one act thatthese “seeings” are accomplished, rather than in two coordinated acts. That is perfectly consistent with the obviousfact that we can distinguish between the conceptual and sensory aspects of the one act. As Hanson writes:

‘Seeing as’ and ‘seeing that’ are not components of seeing, asrods and bearings are parts of motors: seeing is not composite. Still, one canask logical questions. What must have occurred, for instance, for usto describe a man as having found a collar stud, or as having seen a bacillus? Unless he had had a visual sensation and knew what a bacillus was(and looked like) we would not say that he had seen a bacillus, except in thesense in which an infant could see a bacillus. ‘Seeing as’ and ‘seeing that’, then, are not psychological components ofseeing. They are logicallydistinguishable elements in seeing-talk, in our concept of seeing. (p. 21)

As theThomist would argue, we can distinguish between a man’s animality and hisrationality, but it doesn’t follow that his animality and rationality aregrounded in two distinct substances only contingently united. Similarly, we can distinguish between thesensory and conceptual content of a man’s seeingan ice cube or of his seeing that theearth moves. But it doesn’t followthat there are two acts here, an act of seeing and a distinct, additional actof conceptualizing or interpreting what he is seeing.

newest »

newest »

Edward Feser's Blog

- Edward Feser's profile

- 323 followers

>

> Of course,the first astronomer would (as we now know) in this case be mistaken about what he sees.

This is not actually right. In mechanics, and mathematics, we can describe any movement in respect to different references and coordinates. And considering that we calculated it correctly, we can achieve the same description, although using different systems (this is known as change of basis in linear algebra).

There's no reason to say that any astronomer is wrong, they just use different systems, setting the origin coordinates' in different space. The difference is that some systems are "easier" to calculate, explain and fit into a physical theory than others.