Kenneth D. Ackerman's Blog

August 30, 2023

Growing up in the last Century: WASHINGTON IN THE 1970s; FIRST TASTE OF CAPITOL HILL

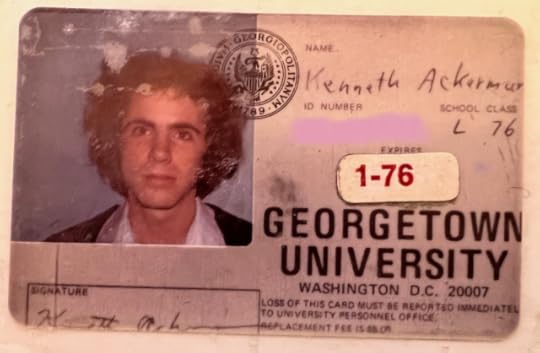

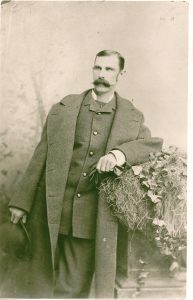

What I looked like on first arriving in Washington D.C. in August 1973, fifty years ago, to start law school.

What I looked like on first arriving in Washington D.C. in August 1973, fifty years ago, to start law school. 1973 had been a big, messy, turbulent year in my life. That January, I’d gone to Rome, Italy, for a study abroad semester, then promptly dropped out of school. I spent the next six months floundering. I landed first in Israel where I lived mostlyon a beach in Eilat with hippies and other dropouts, doing day labor, puttingmy parents through purgatory. Back home,I managed to graduate college (Brown University) without showing up, relying on old Advance Placement credits and snubbing my own graduation ceremony.

I moved in with my parents in upstate Albany,New York, and refused to get a job. I rebelled against anything that came to mind. Tempers flared; thank goodness for my amazinglypatient older sisters and brothers-in-law who ended up acting as reluctantbuffers. I saw a “shrink” for the firsttime (yes, that’s what they called them back then) who accomplished nothing.

Then, after allthe ups and downs, the turmoil and consternation, I landed finally in a weirdlylogical place, at the Georgetown University Law Center in Washington, D.C.

How did thathappen? It’s been fifty years now, halfa century, since I first came to settle here in the DC area. Here I would put down roots, meet my wifeKaren of 38 years, have multiple careers, buy cars and houses, grow older. But back then in 1973, who knew what mightlast, if anything? We were all still shockinglyyoung, me, my friends. The city was oldbut changing. Hardly recognizable fromtoday, we and it both.

From Hippie to Law School

I had never actuallywanted law school. My Dad was a lawyer,and he never seemed to like it much. ButWashington itself was another matter, especially during that unique period ofthe 1970s.

Before 1973 I hadbeen to Washington only twice in my life. And, nojoke, both times I’d had tear gas thrown at me by the National Guard. I had been a student protester against the VietnamWar, first in November 1969, then May 1970 after the Cambodian invasion and theshootings at Kent State University. (Seeearlier blog: Growing Up in the Last Century: Tear-Gassedin Washington DC, May 1970.) These marcheswere fabulous events, drawing hundredsof thousands, the political Woodstocks of that era. I hardly realized at the time that they were shapingme, planting seeds in my mind.

Then, by summer1973, like millions of others, I became mesmerized by the next new drama fromWashington: Watergate, and especially the day-by-day soap-opera-like hearingsof the Senate Watergate Committee under its chairman Senator Sam Ervin (D-NC). I watched them obsessively sitting at home inAlbany, stewing over what to do with my life, fascinated both by the TVjournalists and by all the Senate staffers sitting just behind the Senators andseeming to pull the wires. Who couldimagine a better job than that, right at the center of the action? I couldn’t help but wonder. How do you become one of them?

Back in college,my parents had pushed me to take the Law Boards and I agreed, mostly just to humor them. I was so dismissive that I didn’t bother to prepare, didn’t study. Still, I scored well enough – perhaps because I felt no real pressure - thatmy parents again pressed me at least to apply, at least as a backup. So, fine, I applied to two law schools, oneon the East Coast, one on the West. Georgetownsaid yes, the other said no. All ofwhich led to my third trip to Washington, D.C., in June 1973, to see this GeorgetownLaw School for myself. I’d never visitedor had an interview at the school while applying, so I made an appointment forone now.

On to Washington

I took the trainfrom New York, traveling by myself since I had alienated most of my family andfriends by then. Reaching DC, I walkedthe few blocks from Union Station. GeorgetownLaw had recently moved into a new building on New Jersey Avenue at the foot ofCapitol Hill. That day happened to bethe day John Dean, President Nixon’s recently fired White House counsel and nowchief accuser, was testifying before the Ervin-led Senate Watergate Committee,just a few blocks away. The law schoolhad me wait in the faculty lounge for my interview, and here I watched a gaggleof professors mingling around a TV watching the hearing, chatting about it. What struck me was this: their banter made clearthat virtually every one of them was connected somehow to the big show. This one was advising the Senate, that one theWhite House. Another was best friendswith a key staffer and repeated some delicious gossip, yet another had a columnin that day’s Washington Post or Star.

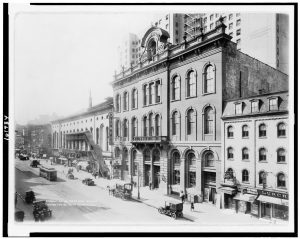

Georgetown Law School, as it looked in 1973, about half-a-dozen

Georgetown Law School, as it looked in 1973, about half-a-dozen blocks from the US Senate Office Buildings,

All this, not tomention Sam Dash, yet another Georgetown Law professor and friends with all theothers, his face right there on the TV screen as Senator Ervin’s committeechief counsel. Here they all were atGeorgetown Law School. Before myinterview even started, they’d sold me on the place.

All the angst andfloundering of the prior year, my neurotic 1973, seemed to resolve itself withthis choice. Maybe I had just beenlooking for control over my own life, a chance to call my own shots. My parents seemed relieved, and so didI. They’d foot the tuition bill; Icommitted to stick it out. And so it went.On one level, Washington,D.C. seemed like a scarred city when I moved there in August and found anapartment within bicycling distance of the law school (since I didn’t have acar). The apartment was between 6thand 7th Streets SE on Independence Avenue on Capitol Hill. Justfive years earlier, in 1968, riots following the assassination of Dr. MartinLuther King had come within a few short blocks of this spot. Many parts of the city remained unrepairedfrom the fires and damage. Capitol Hillrowhouses that today sell for multiple millions of dollars sat on the marketuntouchable. The term “gentrification” wasn’tbeing used yet to describe changes in the wind for neighborhoods like CapitolHill; it would take another decade or so for those to take root. But walking the streets or shopping in thelocal stores, tensions were inescapable.

Richard Nixonstill sat in the White House, J. Edgar Hoover had only recently vacated the FBIby dying in office, and memories of recent police confrontations at anti-warprotests and in the riots after the killing of Dr. King remained fresh.

Buta new energy also seemed to permeate the city in 1973. New waves of people had come here during theKennedy and Johnson years, and the Watergate scandal itself brought a certainglamour to Capitol Hill. Scores of youngpeople wanted to work there and in the press. A Washington music scene was bubbling in places like the Cellar Door inGeorgetown, WHFS on the radio, Irish music at the Dubliner, jazz at BluesAlley, bluegrass at the Birchmere in Arlington, dancing at Déjà Vu, folk at theChancery across the street from Georgetown Law, plus all the big rock concertsat RFK stadium, the Warner Theater, and on the Mall.

Finally, Capitol Hill

Ittook until my third year of law school before I finally had the chance to plantmy flag on Capitol Hill itself. I signedup for a “clinical” program on Legislation where I would get course credit forworking as a Senate intern while taking seminars team-taught by a professor,Roy Schotland, and a working Hill staffer, MichaelPertschuk, the future FTC chairman and then-chief counsel to the SenateCommerce Committee. Finding aCongressional internship meant knocking on doors in the Senate office buildings,no appointments, no friends or contacts, just carrying my sparse resume andasking for a chance.

Ittook until my third year of law school before I finally had the chance to plantmy flag on Capitol Hill itself. I signedup for a “clinical” program on Legislation where I would get course credit forworking as a Senate intern while taking seminars team-taught by a professor,Roy Schotland, and a working Hill staffer, MichaelPertschuk, the future FTC chairman and then-chief counsel to the SenateCommerce Committee. Finding aCongressional internship meant knocking on doors in the Senate office buildings,no appointments, no friends or contacts, just carrying my sparse resume andasking for a chance.

After many triesand failures, I finally got lucky and landed a spot in the office of Senator ChuckPercy (R.-Ill.). Percy was then the top Republican on the SenateCommittee on Government Operations, soon to be expanded and renamedGovernmental Affairs, today Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Senator Percy atthe time was a leading national figure, a liberal Republican back when thoseexisted: conservative on finance but anti-war, anti-Watergate, pro-civil rightsand political reform. He looked andspoke like a Senator straight from central casting, handsome, baritone voice,articulate enough to debate William F. Buckley on his Firing Line TVshow one day, then tangle with Nixon’s White House or Chicago’s autocraticMayor Daley Sr. the next. And theGovernmental Affairs Committee itself, under its chairman Senator Abe Ribicoff(D.-Conn), was experiencing something of a renaissance. It hadrecently produced the landmark 1975 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act,was considering high-profile reforms stemming from the Watergate scandal, and wouldsoon handle key proposals from President Jimmy Carter to create newCabinet-level Departments of Energy and Education. Its Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations,chaired in the 1950s by none less than Joe McCarthy (R.-Wis.), held eye-poppinginvestigations that often grabbed headlines.

The Senate Government Operations Committee, circa 1973, when I first came to D.C. Henry Kissinger is the witness; Senators include (from left) Jacob Javits (R-NY), Bill Roth (R-Del), Chuck Percy (R-Ill), and chairman Abe Ribicoff (D-Conn).

The 1975-76academic year would be brutal for me, working by day on Capitol Hill, nightclasses at Georgetown Law, then followed by an even-more-brutal summer of 1976preparing for the bar exam while taking two more courses needed to finishschool. All this was capped by amid-summer week that included the two-day bar exam, a term paper, plus twofinal exams.

After that last exam, I was spent. All I could manage was to stagger back to mysmall apartment and polish off a bottle of Wild Turkey while staring intospace, no drugs needed. Those were the days. A few days later, I remember joining some friends at the Bicentennial fireworks onthe National Mall amid a crowd estimated at a million people. I still rememberthe brownies we ate and how they made the fireworks extraordinary.

Withlaw school now finished, my Capitol Hill internship soon turned into an actualjob as a young committee staff counsel working for SenatorPercy. There is a popular Washingtonstereotype of all those young Congressional staffers in their twenties pretendingto run the world, thinking they’re smarter than everyone else. That was me in the mid-1970s walking about theUS Senate, arrogant, entitled, mostly scared to death that I was totally out ofmy depth, faking the whole thing.

The La st Great Senate

The Capitol Hillof the 1970s is hardly recognizable compared with the hyper-partisan,dysfunctional Congress of today. Myfriend from those years Ira Shapiro, who was also a staffer on the SenateGovernmental Affairs Committee, captured it in a book he wrote called TheLast Great Senate. It was awonderful place to work, especially as a first job out of school. Like those old Upstairs-

Downstairs TV dramas,the Senators promenaded the national stage while their staffs behind the scenesmingled together in their own world. Partisan divides existed, but we were all friendly back then, Republicansand Democrats. One friend compared it toa college campus, the lawns and buildings and restaurants, the differentcommittee staffs like the different academic departments.

On our Committee, GovernmentalAffairs, the Democratic Chairman Ribicoff and Ranking RepublicanChuck Percy, my boss, saw eye-to-eye on most big things, despite a long list of policy differences. Sen. Percy’sfavorite catch phrase, repeated after any tough meeting, was simply this: “always disagreewithout being disagreeable.” And what akick it was to sit at a table (or rather just behind it) with the likes of Ribicoff,Percy, Jacob Javitz (R.-NY), Charles Mathias (R.-Md.), Lawton Chiles (D.-Fla.),Tom Eagleton (D.-Mo.), Sam Nunn (D.-Ga.), John Glenn (D.-Oh.), so on – all householdnames back then and members of the Governmental Affairs Committee. Seeing them interact, these smart,strong-willed people, each eccentric in his own way, haggling over issues andlegislation like a sophisticated game of three-dimensional poker, countingvotes and hatching schemes, put all those dry theories of legislation in anentirely new human light.

It wasn’t all flowersand roses. Senators had bigpersonalities, with temper tantrums and egos to match. We staffers saw plenty. Some Senators were prima donnas treating theirstaffs like maids and servants. Some showedup drunk at hearings or floor debates (alas, no more with C-Span on thejob). Others failed to do homework,then botched simple questions or speeches or sat clueless in key meetings. Once, while we were having a staff meeting ina committee hearing room, an aging senator walked in and wandered aroundtotally bewildered, unaware of where he was or what he was doing, until SenatorPercy tactfully spoke with him, calmed him, and walked him to his destinationdown the hall.

I was the youngestlawyer on the staff, so I was assigned at first to cover issues involving the PostOffice and Civil Service. For SenatorPercy, the most important of these was to keep an eye on the Federal Hatch Act,which bars partisan politics by career civil servants. Percy came from Chicago, then ruled byold-time Democratic Boss Mayor Richard Daley Sr., and Percy had made fighting politicalcorruption a major theme in his campaigns. My directive on the Hatch Act wasthis: “Don’t let them do to Washington, D.C. what Mayor Daley does to Chicago.” Hands off!!

Oddly, thisassignment would place me in the middle of two major events of the Jimmy CarterAdministration: the Bert Lance hearings and the Civil Service Reform Act of1978.

The Lance Hearings

Things had startedbadly between our committee and President Carter’s White House. In mid-1977, a scandal erupted involving T.Bertram Lance, the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), a topjob in any administration and overseen by our committee. Lance, before coming to Washington, hadheaded the National Bank of Georgia, and Federal bank regulators identified severalirregularities at Lance’s bank. Thescandal escalated into hearings and accusations. Newspapers assigned teams of investigators todig up dirt. Percy and Ribicoffpresented a united front on the controversy, both demanding that Lance resign.But Lance refused and the issue turned bitterly partisan.

It all culminatedin public hearings that September of 1977, covered gavel-to-gavel on CBS networktelevision, the first such televised hearings since Watergate. For our Governmental Affairs Committee, thismeant all hands on deck. Even as thejunior lawyer on staff, I soon found myself poking my face onto the TV screen,one of those staffers sitting behind the Senators as the hearings unfolded, theones who had impressed me so much during Watergate.

The publicity was glaring;given the enormity of it at the time, it is remarkable how this event is solargely forgotten today. It was fun at first. When I spoke to my parents athome in upstate New York, they reported how their friends had seen me on TVand, of course, had focused on the important points: “Why can’t Kenny get ahaircut?” “His suit looks terrible onTV?”

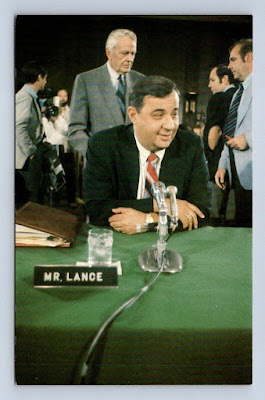

Bert Lance before Governmental

Bert Lance before Governmental Affairs Committee in 1977.

But when Lancehimself finally came to testify, the hearings turned highlyconfrontational. We received deaththreats, directed at Senators and staff alike. At one low point, Carter’s WhiteHouse accused Senator Percy of taking illegal gifts, free airline flights, froma lobbyist. Fortunately, Percy was ableto produce a cancelled check within hours proving he had paid for the flightshimself and the story was fiction, but Carter’s team never retracted norapologized. To poison the well further,several Senators made public accusations against senior committee staff membersbefore it was over.

Within days afterthe hearings, Lance resigned his post at OMB and tempers started to cool. Now I learned another lesson: how politiciansmake peace. After all the bad feelingfrom the Lance hearings, Senators Ribicoff and Percy wanted to heal the wound. Senator Percy was facing re-election in 1978and eager to find a good positive issue to present the voters in Illinois.

Civil Service Reform

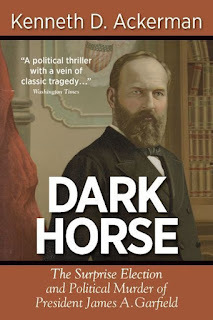

The opportunitycame in early 1978 when President Carter announced his landmark proposed CivilService Reform Act of 1978, which he hoped to make a centerpiece in hispost-Watergate commitment to reform government. It would be the first major rewrite of civil service rules since 1883,when Congress passed the original Pendleton Act after the 1881 assassination ofPresident James A. Garfield by a purported disappointed office seeker. (The experience would later lead me to write a book about the Garfield story called DARK HORSE.)

The opportunitycame in early 1978 when President Carter announced his landmark proposed CivilService Reform Act of 1978, which he hoped to make a centerpiece in hispost-Watergate commitment to reform government. It would be the first major rewrite of civil service rules since 1883,when Congress passed the original Pendleton Act after the 1881 assassination ofPresident James A. Garfield by a purported disappointed office seeker. (The experience would later lead me to write a book about the Garfield story called DARK HORSE.)

And as the bottom-of-the-totem-pole lawyerhandling Post Office and Civil Service issues on the Committee, I found theproject landing squarely on my desk.

Congressional staff members can spend decades working in the House orSenate without ever having the chance to handle a major bill from start tofinish, from hearings to markups to floor debate to conference committee, allin a single year. But so it was for me with the Civil Service ReformAct, an amazing learning experience. Therewere many high points. Probably the mostentertaining was the conference with the House, where we squared off againstour counterpart House committee, led by Congressmen Mo Udall (D.-Az.) and EdDerwinski (R.-Ill.), two smart, funny, creative legislators who knew how to cuta deal. Their antics lit up the room.

The most lastingimpression, though, came earlier. At onepoint just before reaching the Senate floor, the bill became stuck as twoSenators, Ted Stevens (R.-Al.) and Charles Mathias (R.-Md.), put “holds” on it,trying to win concessions for their Federal-employee constituents. We staffers negotiated for weeks with noprogress. Then the Senators got involvedpersonally, but again no progress. Finally, President Carter, seeing his high-profile initiative injeopardy, decided to intervene personally and try to break the logjamhimself. Carter invited the four keySenators, Ribicoff, Percy, Mathias, and Stevens, for a face-to-face, privatemeeting at the White House. As the Senatorsand President spoke behind closed doors in the Oval Office, we stafferswere directed to sit and wait in the nearbyCabinet Room - my first time in the West Wing. After the meeting ended, the Senators came out and told us that they’dreached a deal. Then they drove off,leaving us staffers behind to scratch our heads and figure out the details.

The President Steps In

There we sat inthe Cabinet room, joined by some White House staffers. Aftera few minutes, as we were trying to decipher what came next, a door opened atthe far end of the room and in stepped a familiar-looking man in a suit. I was at the far end of the table and it tooka minute to recognize him as President Carter. We were all a bit startled; we weren’t expecting him. He had come by himself, standing alone, nostaff at his side. He seemed shy,introduced himself in a quiet voice, told us he really appreciated our work, then went around the table and shook hands with each of us.

I had never met a President before in a small group setting likethat. Maybe it was the day, but heseemed tired, face drawn, too many meetings, compelled to go through themotions for this one more group. Maybeone of his aides had insisted. Maybe hejust didn’t want to say no. Carterstayed for just a few minutes, then left through the same door where he’dentered, again thanking us. Nobody took snapshots.

It’s alwaysdangerous to read too much into a single brief encounter, but I always took thisday as a cue for why Carter became a one-term President. Perhaps he just didn’t enjoy it enough. (Clickhere, by the way, for my take on the Carter presidency.]

We finished thebill. They held a big signing event forit at the White House for the Senators, Congressmen, and key lobbyists. And yes, Senator Percy would use it in his reelectioncampaign that year – a surprisingly close race, but that’s a story for anotherday.

White House signing ceremony for Civil Service Reform Act of 1978.

White House signing ceremony for Civil Service Reform Act of 1978.End of an Era

For me, the 1970sended abruptly on Election Day 1980. Itwasn’t that Ronald Reagan won the White House. All the pollsters predicted that part. The surprise came later that night when Republicans captured control ofthe Senate, the first Senate party flip in 25 years. I had spent that night watching electionreturns at a house party for staffers from our Governmental Affairs Committee,mostly Democratic. It was a wrenching,emotional affair. As the hours passed,many people in the room saw their jobs disappear, their future plans turned upside down. Our group of friends was being broken up. I would avoid election-watch parties foryears after that.

The next morning,Republican Senators and staffers were elated. There were celebrations among the winners, shell shock for thelosers. In one Democratic office, pinkslips were circulated at the staff Christmas party. Senator Percy, on the winning side, becamehead of the Foreign Relations Committee, a longtime aspiration. In the new regime, I was assigned at first toa new Governmental Affairs subcommittee where Percy become chairman. One of my first assignments was to hand outparking spaces to the staffers, including the now-minority Democrats. My instructions: “Treat them the exact same waythey treated us.” On our subcommittee,there were sixteen parking spaces and the Democrats had previously given the Republicansthree. So, with mathematical precision,I returned the favor - another lesson in partisanship.

Within months, mytime on Capitol Hill came to an end. That June, I joined the Reagan Team, taking a job at a small financial regulatoryagency called the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, but, again, more onthat some other time.

I would return toCapitol Hill many times over the years, including another round as staffcounsel, this time to the Senate Committee on Agriculture working for Democraticchairman Senator Patrick Leahy (D.Vt.). Inthe 1990s when I became an agency administrator (USDA crop insurance chief), I wouldappear regularly, presenting testimony at committee hearings and markups,finally sitting at the adult’s table and participating in my ownvoice, having staff support of my own.

But what adifference those half-a-dozen years made. By 1980, I was still immature, mixed up, wouldn’t meet my wife foranother couple of years, and still had only the vaguest sense ofdirection. But I also knew that I hadsomething important under my belt, a taste for living history, being part of myown era, having an impact. It made mehungry for more. Stay tuned.

August 29, 2023

Growing up in the last Century: DAD'S POLITICAL CAREER

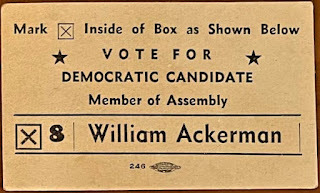

Oneday shortly before my father passed away almost 30 years ago, in late 1994 atage 86, he started talking to me about his brief career in politics back in the1930s. It was an old story. My sisters and I knew bits and pieces. Dad had been a 30-year-old struggling lawyerin Brooklyn back then, had no background in politics, no money, the wrongpersonality (bookish and introverted like me), and no friends in highplaces. Still, he decided to throw hishat in the ring for the Democratic nomination for a seat in the New York StateAssembly.

But there was alwayssomething odd about the story. Dadrarely talked about it, and what we knew had plenty of holes. Only one thing was crystal clear: After this experience, Dad came out with anattitude. “All politicians are crooks. Every single one.” I still remember his tone of voice saying so. Even in the 1970s after I started working asa young lawyer in Washington, D.C. on Capitol Hill, counting several“household-name” Senators on the Committee where I served as staff counsel, includingpoliticians my parents mostly seemed to like. Even then, I still remember Dad singing that same tune: “They are allcrooks. Every single one.”

Where did thisattitude come from? We all have plentyof reasons to distrust politicians, especially my family living as we did inAlbany, New York, with its then-famously crooked political machine. But Dad’s attitude was something deeper, morepersonal.

Brooklyn in the 1930s

Here’s what we knew. Dad first tried his luck inpolitics in 1938, when corruption in big American cities was nothing new orunexpected. Brooklyn, though, played inits own special league. Bossescontrolled nominations and bristled at intruders. Graft and crime permeated the scene. My parents lived in a neighborhood called CrownHeights at 1248 Saint Marks Avenue, barely a dozen blocks, an easy quick walk,from the small candy story called Midnight Rose’s on Saratoga Avenue that then servedas headquarters for the notorious Murder Incorporated gang under the famousmobsters Abe Reles and Albert Anastasio. That set the tone.

But Dad wasidealistic and desperate. An immigrant,he’d reached New York City as a five-year-old from Russia/Poland and grew uppoor even by Lower East Side standards. He had worked his way through St. John’s Law School (class of 1928), attendedmeetings of the Socialist-leaning Lawyers Guild, then earned his legal licensein October 1929, the month of the great Stock Crash. It was literally the toughest month of thecentury to start a career.

Depression Eralawyers struggled and starved. Dadrepresented vagabonds, evicted families, then worked for a real estatetitle company, but nothing substantial. So with a wife, a one-year-old daughter (my big sister Honey), andlittle else to lose, he decided to take a flier at politics.

Brooklyn back thenhad twenty-three Assembly Districts, each electing one member to the State Legislature. These assembly seats were a big deal, prizedpossessions: two-year terms, nice salary, status, and a platform for promotion,a future judgeship, a seat in the State Senate, or maybe a partnership at agood law firm. (And yes, plenty of grafttoo if it suited you, but that’s not what this story is about, at least notdirectly.)

Dad ran threetimes for that Brooklyn Assembly seat, in 1938, 1940, and 1942. During that time, American entered World WarII, but Dad was too old for military service. So he kept plugging away, at lawyering, raising a family, andpolitics. He’d never win, but he keptputting himself out there.

1938: The Good Race

But here’s thething. Of those three races, the onlyone he ever talked about was the first, in 1938. Dad was proud of that campaign. That year, he ran a classic insurgent race. He did everything right: professional-lookingleaflets and handouts (all union printed, of course), neighborhood letters, speeches,and organization. As his centralmessage, he railed against “Bosses” and corruption, claimed to be “the onlyDemocratic Candidate free from domination,” and told his voters to “takecontrol the primary system” and throw the bums out. He shook hands, made phone calls, walkedstreets, and convinced neighbors to back him.

I remember how he and my mother laughed while talking about theirshoestring operation, the meetings in their kitchen, the quirky supporters anddoor-to-door campaigning. Dad, anewcomer, had three experienced opponents in the race, including both theincumbent plus a former office-holder making a comeback. Dad’s opponents, with money and connections,could easily win supporters by promising jobs, patronage, and favors -- letalone paying a few street derelicts a couple of dollars apiece to show up andvote their way. (Yes, they did that backthen.) By comparison, Dad had little tooffer except honesty, a fresh face, some idealism and energy.

With thatcalculus, it’s no surprise he came in last, 4th out of 4candidates. But Dad was playing a longergame. His campaign had caught the eye ofanother aspiring insurgent politician. His name was Martin J. Kelly, an affluent, popular lawyer hoping tounseat the reigning, entrenched Democratic Party leader in that Assembly district.Kelly saw talent in my Dad, became his mentor, and Dad became a leader inKelly’s insurgent campaign for District leader.

With thatcalculus, it’s no surprise he came in last, 4th out of 4candidates. But Dad was playing a longergame. His campaign had caught the eye ofanother aspiring insurgent politician. His name was Martin J. Kelly, an affluent, popular lawyer hoping tounseat the reigning, entrenched Democratic Party leader in that Assembly district.Kelly saw talent in my Dad, became his mentor, and Dad became a leader inKelly’s insurgent campaign for District leader. Should Kelly actuallywin and become the new leader himself, the opportunities for Dad could be huge. Dad would suddenly become the favorite for thatAssembly seat nomination the next time around, or maybe something bigger.

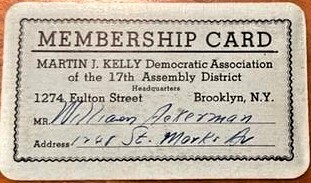

Kelly, to support his campaign, built himself a political club, theMartin J. Kelly Democratic Association, with a fancy office, legions of donors,dances and fund-raising parties, and a slick PR operation. Dad joined the club and became an officer. He headed the publicity committee and paidhundreds of dollars ($25 per month) in dues at a time he could barely make endsmeet. He even listed my Mom and my now-two-year-oldsister as boosters as well.

Kelly, to support his campaign, built himself a political club, theMartin J. Kelly Democratic Association, with a fancy office, legions of donors,dances and fund-raising parties, and a slick PR operation. Dad joined the club and became an officer. He headed the publicity committee and paidhundreds of dollars ($25 per month) in dues at a time he could barely make endsmeet. He even listed my Mom and my now-two-year-oldsister as boosters as well.But here the storyturned murky. Martin Kelly’s bid to replacethe incumbent leader of their Brooklyn Assembly District came to a head in April1940 in a special primary election. Theincumbent was a former City Alderman named Stephen J. Carney, and Kelly lostthe vote. So up in smoke went Dad’s chances to ride Kelly’s coattails to biggerfame. But then something else happened. There was a falling out, and Dad was left onthe short end of the stick.

1940: Not so Good

By the time Dadlaunched his next campaigns for that same Assembly seat in 1940 and 1942, the moodhad changed. Dad never managed to lastin the race even until Election Day. Eachtime, powerful people combined to block him, in ways Dad never really wanted totalk about. All I knew was that, afterthis experience, his attitude toward politicians had solidified. “They are all crooks,” he’d say withfirst-hand authority. “Every one ofthem.”

So whathappened? Shortly before he died in1994, Dad gave me a clue. He left meamong his papers an old, tattered file folder labelled “Bill’s PoliticalCareer” in hand-written ballpoint-pen letters. I looked through the folder at the time, newspaper clippings, some letters,hand-written notes, cards, but arranged chaotically and not shedding muchlight. Too many missing pieces. So I just put it away with other old files whereit sat collecting dust as years and decades rolled by.

Along the way, Ilearned historical research, wrote a few books, including a book about New YorkCity politics (yes, the one about Boss Tweed), and marveled at how new on-linedigital technology was making it possible to open powerful new doors into thepast. So when I happened to pull outthat folder again not long ago – almost thirty years after I’d seen it thefirst time -- it occurred to me that now, today, with modern on-line researchtools, I might have better luck.

I soon madea new best friend: the now-digitized, searchable Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The Brooklyn Eagle had been one of thebest newspapers in America during its hay-day in the late 1800s and early1900s, and it covered those local State Assembly races with loving care.

I soon discovered,to my surprise, that my Dad had made a friend in the media.

Solet’s pick up the story: Where we leftoff, Martin Kelly, the insurgent lawyer who had taken Dad under his wing, finallyhad his big moment. Kelly's chance to unseat the entrenched leader/boss of their Brooklyn Assembly district,Stephen Carney, came in the primary election of April 1940. Kelly and Carney both fought hard and Dad gotvery involved in the campaign. Kelly, inhis brochures, described Dad as the “independent assembly candidate of 1938”and listed him as a major backer and coalition partner. Dad spent primary day that April working as a voting inspector, watchingthe count at a key polling place to guard against cheating.

Dad's hand-scribbled tally sheet as voting inspector for the Martin Kelly campaign, April 1940.

Dad's hand-scribbled tally sheet as voting inspector for the Martin Kelly campaign, April 1940.In the end, Kelly lost decisively, by a big enough vote margin toavoid any run-off or any claims of fraud. For Kelly, that was it. A fewdays later, Kelly and Carney met privately and decided to call off thefight. They made peace. They cut a deal. Kelly returned to his private law practiceand promised to forget all about politics.

But what aboutKelly’s followers, the more radical ones, the bitter-end true believers in “reform”? They were in no mood to make peace.

My Dad back in1940 still fell into this latter category. He had spent years railing against corrupt “Bosses” like Stephen Carney,and he seemed genuinely surprised that his mentor, Martin Kelly, would makepeace with the enemy. So Dad decided tostick it to both of them. That November,there’d be an election for that same old Assembly seat again, with a primary inSeptember. Dad would stand on principleand challenge Carney’s hand-picked candidate, a well-heeled incumbent namedFred Morritt, even without help from a mentor like Martin Kelly. Dad would do it himself. Game on!!

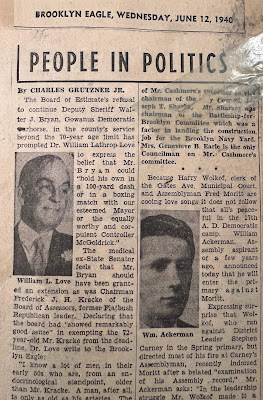

Dad was not totally alone in this quest. At this point, he seems to have nurtured arelationship with a political reporter at the Brooklyn Eagle namedCharles Grutzner Jr. who penned a daily column called “People inPolitics.” Grutzner would later winawards investigating organized crime for the New York Times in the 1950sand 1960s. Where better to cut yourteeth than covering crooked local politics in 1940s Brooklyn?

Grutzner, thoughhis “People in Politics” column, had been the first to disclose the peace dealbetween Kelly and Carney. And when Dad decidedto break that deal by launching his own independent challenge for the StateAssembly, that was news! Grutzner featuredthe story in his column, including a photo of Dad right there in thepaper. Then, as primary day approached, Grutznerran a second story about Dad’s campaign, this time quoting Dad at length blastingthe Carney-Kelly peace deal and asking disaffected Democrats to rally tohim. “My headquarters shall be at myhome, 1248 Saint Marks Ave.,” he quoted Dad as saying. “I ask all independentDemocrats, all those Democrats who desire real representation in the Assemblyand all those Democrats who love truth and justice, to communicate with me andsend me a word of confidence and support.”

This second article,dated August 9, 1940, seemed to really irritate the now-unchallengedleader/boss of that Assembly District in Brooklyn, Stephen Carney. Withinhours, Carney decided to act. Dad received a message. Be it byphone, telegram, or word of mouth, call it an invitation, a summons, a demand,whatever you like, but before the day was out, Dad was required to appear at theoffice of his nemesis, the boss Stephen Carney, and sit down for a meeting,face to face.

The Private Meeting

Grutzner, the BrooklynEagle reporter, learned immediately about the meeting and reported on it inhis column the next day – an article that was missing from Dad’s old filefolder. Bottom line: Dad was droppingout of the contest. “William Ackermanwithdrew today from the 17th A.D. Assembly race, giving DistrictLeader Stephen J. Carney a perfect score in clearing primary hurdles out of thepath of his Assemblyman Fred Moritt. The ink was hardly dry on Mr. Ackerman’s denunciation” of theCarney-Kelly peace pact, Grutzner said, “when Mr. Carney sat down with Mr.Ackerman for a long talk which resulted in the young lawyer’sannouncement.” Grutzner quoted Dad asciting “Democratic unity in this important Presidential year” as his reason forquitting the race.

Oh, to have been afly on the wall for that “long talk” between Stephen Carney and my Dad that dayin 1940! What actually happened behindclosed doors? On reading the BrooklynEagle article, how I wished I still had Dad around to ask that question, oreven Mom who certainly would have known the bloody details. But neither of them ever mentioned it duringtheir lifetimes, so it probably wasn’t pretty.

What form ofarm-twisting did Carney use? Did heshout and make threats? Did he use charmand diplomacy? “Let’s be reasonable,” orsome nonsense like that? Did Carney perhapstry to win Dad over as a new protégé? Ordid Dad try to win over Carney as a new mentor? Maybe Carney promised Dad a fair shot at a primary for another job. Or maybe he promised something else. Who knows?

The only thing wedo know is the outcome. It was not friendly, and they didn’t pretendotherwise. There was no good feeling. The bridge, if it ever existed, wasburned. When it was over, Dad simply deliveredthe cold, terse message to the reporter, who announced it in the BrooklynEagle, and that was that. Or was it?

1942: Unleash the Lawyers

Allof which brings us to 1942, when Dad again announced his candidacy for thatsame damn seat in the New York State Assembly. Why did he decide to run again? Certainly, he knew he had no chance. He knew he’d made enemies. Was it pure stubbornness? Or perhaps finding out Carney had lied tohim, broken whatever promises he had made to get Dad out of the race in 1940?

Eitherway, this time Leader Carney and his incumbent Assemblyman Moritt were notamused. This time, instead of a politemeeting, they decided to sic the lawyers on Dad.

Moritt, the Assemblymanincumbent, promptly filed a lawsuit before a local Brooklyn Judge accusing Dad offraud. The legal complaint claimed thatDad, in his nominating petitions, had included dozens of names that were faultyor fraudulent, and demanded that Dad’s name be stricken from the ballot. Dad was incredulous. That corrupt pol, that conniving little wire-pullingBoss, was accusing him of fraud!!? My Dad could be accused of many things: stubbornness, bad judgment, thelist goes on. But fraud? My Dad was the kind of person who paid billswithin 24 hours and kept receipts for everything. Punctilious to a fault. Fraud?

The chargehorrified my Dad enough that he promptly filed a defamation lawsuit againstMoritt to protect his good name. Hedemanded damages totaling $50,000, a huge sum of money back then. With no money to hire lawyers, Dad filed thecase himself, tapping out the complaint on his old Remington manualtypewriter. (I still have that antiquemachine in my house.) In it, Dad calledMoritt’s accusations “wholly false” and intended for “the malicious purpose ofdegrading and intimidating” him, to destroy his reputation and “scare” him outof the race. I can easily imagine theloud banging of the typewriter keys as Dad hammered out those words, trying toavoid misspellings and typos in this age before computers, “white-out,” orcorrection tape.

I don’t know whatever became of that lawsuit. It probablynever got far; it’s not mentioned in any of the newspaper reports and, again,he and Mom never mentioned it during their lifetimes. Nothing in the files. But the fix was in. A few weeks later, the Brooklyn judge issueda ruling throwing out the nominating petitions for sixteen different insurgentcandidates fingered by Carney and other local Bosses, including Dad’s, removingall of them from the primary ballot. That’s how the Brooklyn machine did its dirty work in 1942.

So ended Dad’sforay into the bare-knuckled world of New York City politics. He never won that Assembly seat nomination,his mentor Martin Kelly never became district leader, and Dad walked awayfeeling cynical about the whole mess. Tohis credit, Dad had scared the Bosses into taking him seriously. In those second two races, 1940 and 1942, theynever beat him at the ballot box, but instead torpedoed him behind closed doorsand in a trumped-up lawsuit. That was aneducation in political science you don’t get from a university.

A few years afterthese events, Dad would take a competitive New York State civil service examand win a job in the New York State Attorney General’s office on his ownmerits, with no nods from politicians. This was the way he probably would have preferred it all along. The move finally brought our family toAlbany, the state capitol, where I was born in 1951. Working in the State Attorney General’soffice, Dad had the chance to play a key role in acquiring the land for buildingthe New York State Thruway, the Long Island Expressway, and other key highwayprojects of the 1950s and 1960s.

Dad may have feltdefeated, even embarrassed, over the way the Brooklyn political bosses muscledhim out of his primary election campaigns in 1940 and 1942. It’s not the kind of story you like to sharewith your kids over the dinner table. Butthat’s how life works: People who standup to bullies often lose and get knocked down; people who get back up to try againoften just get knocked down again even harder. But the fact is, Dad was lucky. He won his battle. In the end, hewas able to walk away, reject a system that had lost his respect, and succeedon his own terms. Ironically, even hadhe won, Dad probably would have hated being a New York State Assemblyman. It hardly fit his stubborn personality, andhe probably would have grown just as cynical of politicians watching them workup close and personal.

I’m glad I finallymanaged to find the tougher side of the story that Dad tried to downplay all thoseyears. Telling the full version only makeshis stand against the Brooklyn politicians all the more admirable. Yes, they were crooks. And I’m glad my Dad was someone who took hislumps trying to take one down and still managed to walk away.

January 9, 2022

Growing Up in the Last Century-- MY FIRST TASTE OF POLITICS: GETTING KICKED OUT OF THE POLLS BY THE ALBANY MACHINE, June 1972

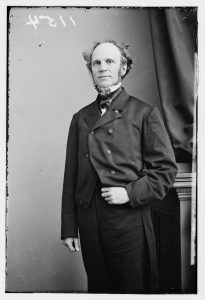

Albany's long-time Mayor Erastus Corning with Democratic Party Chairman Dan O'Connell (with hat), circa 1970.

Albany's long-time Mayor Erastus Corning with Democratic Party Chairman Dan O'Connell (with hat), circa 1970.

This story is complicated, so bear with me.

I was just a 20 year-old college kid when I got my first real bloody nose – figurative and almost very literal – in the political world. Welcome to Albany, New York, my hometown (scenic aerial photo above), back in the days of the Democratic machine, party boss Daniel P. O’Connell, and mayor-for-life Erastus Corning.

Getting the Politics BugI had just finished junior year that summer of 1972. I was living at home with my parents and had a dull summer job for the New York State government. Any excitement was welcome.

By then, I had gotten the political bug from attending a few anti-Vietnam war protests at school and had even volunteered to do grunt jobs in a few campaigns – including handing out leaflets on New York City street corners for unsuccessful 1970 NY Republican-Liberal Senate candidate Charles Goodell. (He’d end up losing to Conservative James Buckley, another learning experience.) Earlier, in high school, I’d joined my friend Bill Greenbaum to do after-school volunteer envelope stuffing for 1968 presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy.Luckily, that s

ummer of 1972 offered a new drama, the George McGovern campaign.

Who was George McGovern? Senator George McGovern (D-SD) would win the Democratic nomination that year only to lose in a landslide to Richard Nixon. But most people remember that campaign for the great scandal it produced, the Watergate burglary and cover-up, leading to Nixon’s 1974 impeachment and resignation. (I would later work in the Watergate Building for my law firm OFW Law, and McGovern would join our firm there, but that’s for another time.)

But for me, there was something more.

George McGovern’s 1972 campaign seemed miraculous at the time, a long-shot crusade by an unapologetic anti-war, anti-establishment liberal. McGovern faced enormous odds, but had won a surprising string of early primary victories. And one of the biggest, most important primary contests that year would be the one in New York State, whose 248 delegates could make or break his quest.

New York would hold its primary on Tuesday, June 20, just a few weeks after I’d come home from college, and the campaign had put out a call for volunteers. So off I went to sign up. My parents didn’t argue; they were happy just to get me out of the house.

The Albany Machine

Now about Albany, my hometown, allow me a quick word: Albany in 1972 had a special reputation. Since 1919, Albany had nurtured a local political machine among the most powerful and autocratic in the country. Our mayor, Erastus Corning, had already served 30 years in office, a tenure that would last over 40, a Guinness record.

But the real power, everyone knew, sat with Party Chairman Dan O’Connell and a handful of lieutenants, including two brothers named Charlie and Jimmy Ryan. Charlie and Jimmy Ryan both sat on the party executive committee, and Jimmy also served as Albany County Purchasing Agent. A state investigation in the early 1970s had uncovered payoffs and overcharges in his office of 500 percent or more, and stories of political strong-arm tactics, vote rigging, and the like were regular features in the local press.

Jimmy Ryan, it so happened, lived in our neighborhood, and was friends was my Dad. In fact, Jimmy was friends with everyone. That was his job. If anyone in his territory needed anything from the city or county, he made sure they got it. Jimmy also made sure they paid him back on Election Day. That was how political machines worked – that, plus the kickbacks, intimidation, vote-rigging, so on. (Please don’t act surprised. This isn’t new news.)Dan O’Connell, the party boss, already in his 80s, found little to like in George McGovern. Not that Dan was “liberal” or “conservative.” Dan’s Machine had delivered Albany’s votes for candidates of all stripes over the years. But what Dan resented most was outside interference. The great Albany writer William Kennedy, in his awesome history of my hometown called O Albany, explained:

In 1972 when the volunteer campaigners for George McGovern’s presidential candidacy were working miracles in primaries around the country, bringing out the student and youth vote, they descended on Albany, ready for another blitz, only to find Dan hostile to their plans. “I’m running the campaign with our own organization,” he said, “and we don’t want any separate campaign here.” The McGovern crowd persisted, and so Dan put himself on the primary ballot as the head of an uncommitted delegation; for Dan preferred Hubert Humphrey or Scoop Jackson [over McGovern].

And so the stage was set for a great head-to-head Primary Day contest: Dan O’Connell’s uncommitted slate versus the McGovernites. Dan had placed the machine’s prestige on the line. He was not going to lose.

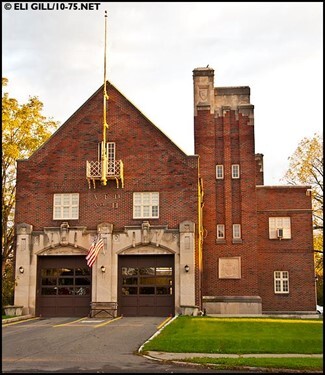

Enter the Naive Young Volunteer The firehouse on New Scotland Avenue, where people in our neighborhood always voted.

The firehouse on New Scotland Avenue, where people in our neighborhood always voted.My assignment as a McGovern volunteer that day was to be a poll watcher at the polling place closest to my house, the firehouse on the corner of New Scotland Avenue and Maplewood Street. I knew the place well; it had a big field next to it where we kids had played touch football, and my Dad had taken me to see the big red firetrucks. I passed it almost every day walking to school or around the neighborhood. This was where people on our street had voted on Election Day for years.

I had never been to a voting place before. Just a few months earlier, late 1971, the national voting age had been lowered from 21 to 18, and I was still just 20, so this would be the first time kids my age could vote, let alone show up as poll watchers.

Why choose me for this job? I got my answer the night before Primary Day when the McGovern campaign pulled together all us young volunteers assigned to watch polls – about a dozen of us – for training. It was like preparing for battle.

A senior McGovern campaign staffer -- I don’t remember his name – told us they definitely expected the machine to cheat, and our job was to watch the voting and report anything suspicious. They’d have lawyers standing by to rush in and take charge. We junior volunteers would be the scouts, the messengers.

To prepare, they gave us a crash course on all the different, creative ways Albany pols had found over the years to cheat on Election Day with paper ballots or primitive voting machines. The list was endless: hiding pencil leads under a fingernail to invalidate ballots, placing vote machines at an open window to read them from the back, paying $5 per vote, so on. Then came our prime directive: Before reaching the polling place, we each needed to locate the nearest pay telephone booth (no cell phones back then), and make sure we had dimes and quarters in our pockets, to call in an emergency.

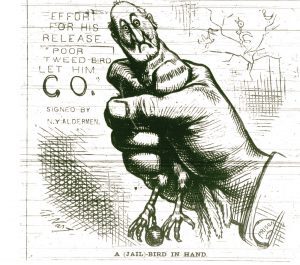

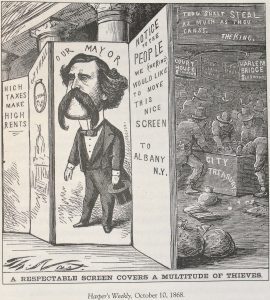

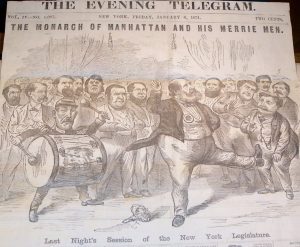

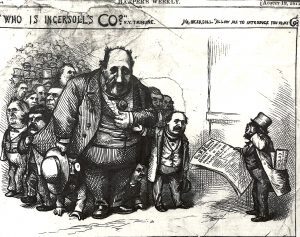

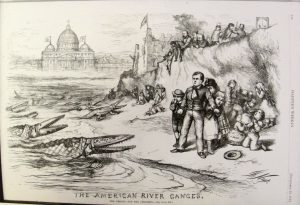

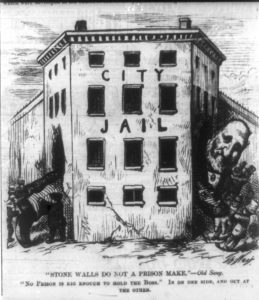

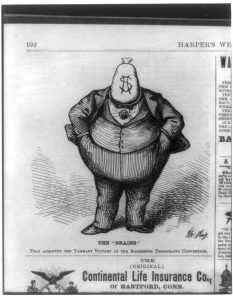

Thomas Nast cartoon vision of Boss Tweed counting the votes in 1870 New York City. Was this what we were walking into?

Thomas Nast cartoon vision of Boss Tweed counting the votes in 1870 New York City. Was this what we were walking into?So on Primary Day, off I went to the firehouse with my credential letter from the campaign, for my first experience ever inside a polling place.

At the FirehouseInside the firehouse, in one of the garage bays usually occupied by an enormous red firetruck, they had set up a desk where the voting officials now sat with their list of registered voters and a pile of paper ballots. A voting booth was set up at a far end of the garage. No voting machines at the firehouse, just paper. People from the neighborhood came, lined up at the desk, gave their names, received a ballot, and could take it to the booth to fill out. Then they would place the ballot in a large wooden ballot box with a slot and an old-fashioned lock on top.

But then came the morning’s first surprise. Managing the polling place as chief voting official this morning was Jimmy Ryan himself, accompanied by two family members. I had never met Jimmy Ryan, though my Dad had mentioned him a few times. Jimmy was, after all, our ward representative. Jimmy had even helped my Dad get a summer job for me one year with the County.

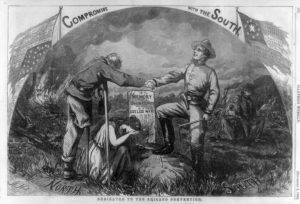

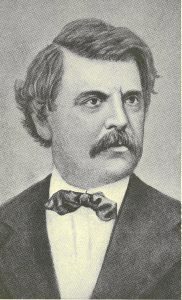

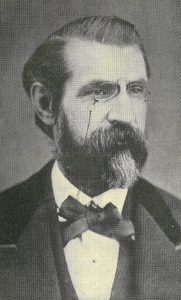

Jimmy Ryan, circa 1970.

Jimmy Ryan, circa 1970.To the McGovern lawyers, though, Jimmy Ryan was part of the enemy camp. So where did that put me? It did seem strange, this arrangement, that every voter, to receive a ballot, had to come face-to-face with Jimmy, a top lieutenant in the Democratic machine, whose leader, Dan O’Connell, had his name on the ballot. But that was how it was.

I remember introducing myself, showing Jimmy my credentials, and his politely leading me to a metal folding chair along the side of the firehouse where I could sit. Let’s be frank: Sitting down, I felt totally out of my depth. Being inside a polling place was utterly new and foreign to me. I had no idea what was normal. Jimmy and his co-inspectors were easily twice my age and experienced professionals.

I was on my own. All I could do for now was sit there and watch.

So that’s what I did. And here’s what I saw. For one thing, everyone was very chummy. Jimmy and his relatives, the voting inspectors, chatted up all the neighbors as they came to vote. But more, they also seemed to know something specific about each person. They raised it in a casual, friendly way. How does your son like his new job? How to you like the new sidewalk in front of your house? The new street lamp? Did the city fix that problem with your utility bill? Or your tax assessment? Or your court date? No pressure. Just asking.

Then I noticed something else. Most people in the neighborhood, after taking a ballot and talking with the Ryans, decided to skip the voting booth altogether. Why walk all the way to the back of the garage? They’d rather just mark their ballots right there at the front table. Sure, Jimmy Ryan could see it, but it was their free choice. No pressure. Just being friendly.

Sitting there in my poll-watcher seat, I fidgeted, cogitated. Was this a problem? Yes? Maybe no? As a first timer with no experience, self-conscious, afraid of looking silly, I continued to just watch.

Finally, after about an hour, I saw this: Two or three of the people coming to vote, after they got their ballots, made a point to walk with one of the Ryans over to a nearby firetruck. From where I sat, I could just see well enough to notice that, after the voter filled out his ballot, one of the Ryans would sign a paper and hand it to them. What was the paper? I had no idea. They seemed friendly. They laughed. Nobody acted out of place.

Asking A QuestionBut now I felt totally uncomfortable. That signed piece of paper, whatever it was, it had to be something. It couldn’t be nothing. But what could it possibly be? I tried to rationalize. There had to be some obvious, innocent explanation. But, racking my brain, I just couldn’t think of one. So, finally, getting up my courage, I decided I needed at least to ask a question.

I got up, walked over to Jimmy Ryan, got his attention, and, in probably the most timid, insecure voice he had ever heard, I said something like this: “Um, er, um, is he, um, actually allowed to do that?” Then I mentioned what I saw about the voters walking to the firetruck and receiving a signed paper.

Jimmy looked at me and, without hesitation, said the following: “You get the hell out of here!” That’s not all he said. There were more expletives. But that’s the part I remember, that and the loud voice.

I asked why, said I was a poll watcher just asking a question and had a right to be there. I showed him again my piece of paper. He looked at it and said: “You’re underage! You’re not 21.” I mentioned that the voting age had just been lowered to 18, but he said he didn’t care, or didn’t know, but “Get the hell out of here!”

One other small detail sticks in my memory: Right in the middle of this exchange, Jimmy’s face just inches away from mine, I noticed a sudden quizzical look in his eye. He was staring at my chin. A few days earlier, a doctor had removed a small growth there and left some stitches, one apparently sticking out, out of place. Without hesitation, Jimmy absent-mindedly reached and tugged it off, like straightening my collar so I would look OK, like a parent or uncle would do. An instant later, he was back to business.

Calling for BackupFortunately, I remembered my training from the night before. Rule One: Don’t argue! Instead, if an argument breaks out, leave immediately, go to the phone booth, call the office, and get help.

So that’s what I did. I said “OK” or something like that. Then I left, walked over to the phone booth down the street, dialed the McGovern campaign, and told them what just happened. But rather than being alarmed, they sounded happy. “Wait outside in front of the firehouse,” they told me. Help was on the way.

I waited there and, within about ten minutes, a caravan of three large cars pulled up, including lawyers from the McGovern campaign, lawyers from the New York State Attorney General’s office, and a news crew from Channel 6, WRGB, one of our three local TV stations. The lawyers had been waiting all day for the chance to pounce on an actual case of voting fraud. So too the TV news. Here was their chance.

They quickly found me, heard my quick explanation, then the lawyers ran ahead to the firehouse, leaving me behind. Things got confusing. There was shouting, pushing, arguing. I remember a fist fight between one of the Ryans and one of the lawyers, wild punches thrown back and forth, bloody faces. In the process, a table was knocked over, a wooden ballot box fell on the concrete and cracked opened, dozens of white ballots flying in the air as frantic voting inspectors ran after them.

Minutes later, I was standing in front of the Channel 6 TV camera, someone holding a microphone, Jimmy Ryan standing at one side holding one of my arms, a McGovern lawyer holding the other. I had only been on TV once before in my entire life at that point, for a local kid’s show called The Freddie Freihofer Show when I was three years old. All I remember of the interview now was this: Once the camera started, they barely allowed me to get in a single word. Instead, Jimmy Ryan and the McGovern lawyer each broke in, tugging me back and forth as they spoke, each insisting he was my best friend. I remember Jimmy dominating the interview, explaining it was all nothing, just a misunderstanding about the confusing new rules for the 18 year-old vote.

So it went for about an hour, the lawyers haggling, inspecting any scraps of paper they could find, looking for evidence, while Jimmy and his inspectors kept collecting the vote.

My Dad Shows UpFinally, after things had barely calmed down, my Dad came over to vote. He had not heard yet about the trouble. When he arrived, Jimmy Ryan went up to him and told him. They pulled me aside. Jimmy patted me on the shoulder, said I was OK, just doing what I was supposed to, sticking up for my side. No hard feelings.

Sure enough, my Dad, no fan of McGovern, voted the machine ticket and make no secret of it.

That night, Channel 6 TV News carried a short piece about the incident at the firehouse. They flashed a quick image of me standing between Jimmy Ryan and the McGovern lawyer, then couched the whole story simply as confusion over the new 18-year-old voting law. No mention of any cheating. Nor did the State Attorney General lawyers ever bring charges. I asked one of them about the mysterious signed papers I’d seen being handed to voters by the firetruck, and he said they were probably tax documents, but he couldn’t prove it.

Dan O’Connell’s ticket won by a mile. George McGovern carried New York State, a key victory on his road to the Democratic nomination, winning 230 of the 248 delegates up for grabs. But not the ones from Albany County.

Like most things growing up, it took years before I really understood what I had seen that day at the Albany firehouse. In 1973, I would move to Washington, D.C. to start law school, and soon start working for a U.S. Senator named Charles H. Percy (R-Ill), a liberal Republican who carried a special grudge against another local Democratic political machine, the one in Chicago. Seemed like a perfect fit.

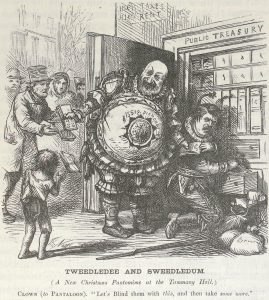

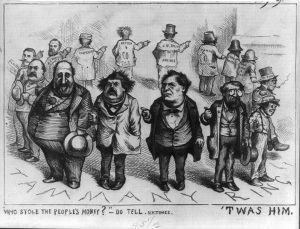

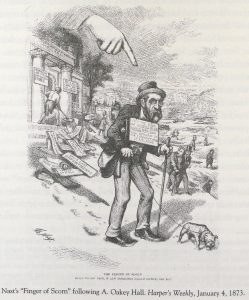

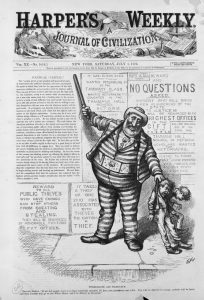

Later, of course, I would develop a fascination with New York City’s Tammany Hall, the biggest, baddest political machine of all, and its leading light, Boss William M. Tweed. It all seemed familiar. I’d even write a book about him called BOSS TWEED: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York. Check it out on Amazon or Audible.

The old O’Connell machine is long gone in Albany. Dan O’Connell himself died in 1977 at 91 years old. After his death, Charlie Ryan would lose a power struggle to Mayor Corning, who would continue as Mayor until his own death in May 1983, a total of 41 years in office. The Corning-Ryan power struggle would become grist for a 2019 off-Broadway play called The True. According to William Kennedy’s book, Jimmy Ryan would die in Florida in 1979 after an illness.

I was no hero that day at the firehouse in 1972, just a nervous, tongue-tied, inexperienced kid trying not to screw up my morning as a campaign volunteer. But the cheating was just so flagrant that even a first timer like me couldn’t fail to spot it. And it didn’t take a big, fancy speech to make the point – just a simple question, a phone call, then letting the chips fall where they may.

But was Jimmy Ryan really a villain? Sure, there was corruption back then. Famously so! But, for a politico like him, his main job was to do favors, make government deliver for people in his neighborhood. All he and the machine demanded back was loyalty. A fair bargain? Not perfect. The corruption and strong-arm tactics not helpful, nor even necessary.

As for his throwing me out of the firehouse that day in 1972, it’s hard to hold a grudge. Bluster aside, he was just doing his job that day too, trying not to screw up his morning delivering the vote for his maestro Dan O’Connell and the machine. Politics was and remains a team sport. You need people who can block and tackle. They made the wheels turn for Boss Tweed in the 1870s, for Dan O’Connell in the 1970s, and plenty in between, including plenty of good guys. In those couple of hours, Jimmy Ryan taught me more about politics, the real-life, street-level kind, than I could have learned from years of college courses or Capitol Hill seminars. For that I thank him.

December 21, 2021

Growing Up in the Last Century: TEAR-GASSED in WASHINGTON, D.C., May 1970

I was just 18 years old, a college freshman, on May 4, 1970, when National Guardsmen in Ohio opened fire and killed four student protestors at Kent State University. Fifty years later, I still remember the looks on peoples’ faces as news of the shootings spread like lightning across my own college campus a thousand miles away at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.

Those were dramatic times President Richard Nixon had just announced his invasion of Cambodia that week. I remember watching Nixon give that speech in a crowded dorm room on a small, grainy black-and-white TV as people shouted, hooted, threw things at the screen. With news of the Kent State shootings, our campus within hours was on strike. (Listen to the original speech on YouTube here.)

Brown University in 1970 was a relatively small school that had just undergone a major change in response to student protests the year before: the adoption of a New Curriculum featuring optional grades, no course requirements, and more student control. My class was the first of this experiment, adding to the sense of tumult. And now the school had shut down. Classes were suspended. (See photo of campus demonstration I took that week, above.)

On Strike!!The campus quickly erupted in protests, pickets, meetings, fevered gossip. Questions raged over whether the school would cancel final exams, how grades would be assigned, what to do about graduation. Rock and roll music blared from dorm windows, making the scene electric. Ours was one of over 400 colleges on strike that week – the largest student protest ever. If campus protests ever had the chance to make any difference in the real world, now seemed the time. How exciting to be caught up in this extraordinary moment!

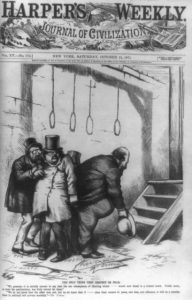

Driving all these events was the Vietnam war, by 1970 in its fifth year with more than 500,000 American troops deployed and no end in sight. Hundreds of American soldiers were dying every week along with thousands of Vietnamese. And we college kids felt ourselves directly in the target zone. The Selective Service, the draft, hung over our lives like a noose, ready to pull us out of school or snap us up the minute we left, then ship us off to kill or die. Over 2.2 million kids around my age, all men, were drafted during the Vietnam War from 1964 to 1973. Tens of thousands never came home alive.

The next summer I would see my own name come up in the draft lottery. Number 14 (out of 365). A bullseye. The War was no abstraction. It was tangible, immediate. And nobody was neutral about it. For my viewpoint, there seemed nothing honorable or patriotic about this conflict halfway around the world. We seemed to be fighting on the wrong side, killing people we didn’t know and had no quarrel with, wreaking pointless oceans of pain and loss, our own government using bully tactics here at home, lies, police clubs, and undercover spies, to stifle dissent. Obviously, plenty of people disagreed.

[caption id="attachment_2334" align="alignleft" width="448"] Photo of anti-War protest in Providence that week.

Photo of anti-War protest in Providence that week.The killings at Kent State of white, middle class protest kids just like us got more publicity, but these weren’t alone. They came on top of similar killings at Jackson State College in Mississippi and Berkeley’s Peoples Park, let alone the police riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago just two summers before in 1968. Construction workers had beaten up protestors that week at the World Trade Center site in New York City. Richard Nixon had publicly called us all “bums.” Passions ran red hot, fear, anger, a loyalty to generation, my circle. It was “us” and “them.”

The war had already colored my first year of college. The protest movement was everywhere. Already I had participated in two large protest marches that fall: In October I had traveled to New York for the first Moratorium Against the War, a raucous march of 100,000 people from Columbia University down to Bryant Park some 60 blocks away. (On that trip, I also had the chance of a lifetime to attend the deciding game five of the 1969 World Series with my nephew Jim, also unforgettable.) Then, a month later, I had travelled south to Washington, DC - my first trip ever to what would become my home of 40+ years – for the November 1969 Moratorium, which drew half a million people marching up Pennsylvania Avenue to the Washington Monument to hear Peter Paul and Mary and a raft of speakers.

That day in Washington I even got to march with the charismatic writer Norman Mailer. My friend Lou Peck and I spotted Mailer along the route and joined his group of friends for a block or so. Before nightfall, I’d had my first whiff of tear gas from the National Guard. I loved being involved in the movement, the marches, the protests. It felt like the most important thing I had ever done with my life – far more exciting and relevant than mere college classes or anything else. And yes, I admit, it was fun! Action!

So when the chance came in May 1970, just days after the Kent State shootings, to join a handful of classmates and a professor and drive overnight down to Washington, D.C., this time to participate in a hastily-called protest over the Kent State shootings and the Cambodia invasion, I jumped at it.

Me as a student at Brown University, 1972.

Me as a student at Brown University, 1972.On to Washington!!

I’ve forgotten many details about that trip more than fifty years ago. How I wish I’d taken notes! Professor Strauss, who drove us down to DC, taught Applied Mathematics at Brown, and I had taken a basic class he taught on computers. There was no such thing as a computer or IT department at the time. These machines remained exotic, rare animals back then, cumbersome, primitive, mysterious. What passed in 1970 for a basic course in computers involved punch cards, endless loops of coding, and reams of print-out pages. No screens, no mice, no cool-looking gear. They were fascinating, but hardly seemed practical or useful in any way. Times would obviously change on that score.

I remember how, reaching DC, we stayed overnight with friends of the professor who had a house in the Maryland suburbs. We were just a handful, the professor plus three or four students. I remember arriving at the march itself the next morning in the professor’s car, a station wagon. Where did he park the car? As an adult, I would have obsessed the entire day over that question. As a protest kid, I never even noticed. Even now, when I think of that day, I still wonder about it.

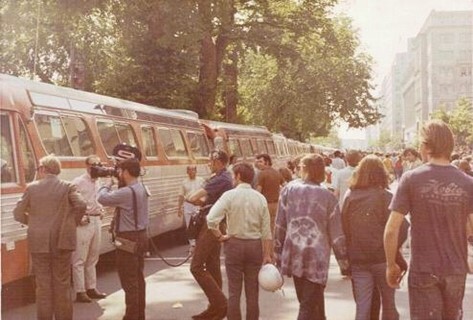

The rally took place on the Ellipse, the park in Washington just south of the White House and across from the Washington Monument. Newspapers estimated the crowd at 100,000, congregating since the night before. President Nixon had actually slipped out of the White House and visited some of the protestors camping out around the Lincoln Monument in a creepy, awkward pre-dawn exchange. The White House grounds themselves had been circled with buses parked bumper-to-bumper, sealing off the area as Secret Service and other troops mobilized inside. Armed police and National Guard were visible everywhere on the street.

And then there was the weather. That day, May 9, was hot, a special condition local Washingtonians know all-too-well as Hazy, Hot, and Humid. For outsiders like me from colder climates up north, the thick heat could knock you down or take your breath away.

Arriving at the rally, we were met by some of the march organizers. When Professor Strauss told them we came from Brown University – considered a relatively moderate campus -- they decided to give us armbands and assign us as marshals. Our job was to help cordon off a small area near the front stage that served as a first aid station with doctors and medical tents -- a busy place that day with kids passing out from the heat or experiencing side effects from the many underground drugs of that era.

I don’t remember much of the big rally itself. There were speeches, cheering, noise, people, music. TV cameras and news crews dotted the scene. But the real action came after the main event broke up. By then, late afternoon, after hours in the heat, marinated with drugs, beer, and lots of sitting around, most of the people seemed wiped out. The Washington Post noted how the heat made this crowd more passive, less agitated than at other recent demonstrations. But not all. Others just got impatient.

Up at the front where we were, a few march leaders decided we hadn’t finished yet. They had brought half-a-dozen wooden boxes to use as props, shaped like coffins and each one draped with a sign for one of the recent shootings: Kent State, Jackson State, Peoples Park, so on. Wouldn’t it be a great idea, they announced, to carry them around to the front of the White House and deliver them to the doorstep of that murderer inside, Richard Nixon himself. Cheers rose up and off we went. Our entire part of the crowd got up and started marching toward the White House.

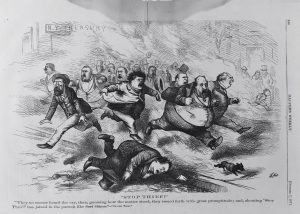

Off to Storm the White House!!I have checked this part of the story against newspaper accounts, just to make sure my own memory hadn’t gotten it wrong. And in fact, according to the Washington Post and other sources, a group of about 10,000 splintered off at that point on a mission to deliver those prop caskets to the president’s door. We marched from the Ellipse up 15th Street past the Treasury Building, then around the perimeter of bumper-to-bumper busses toward Pennsylvania Avenue.

Photo I took of our crowd marching up 15th Street that day. Notice the many hard hats and bandannas.

Photo I took of our crowd marching up 15th Street that day. Notice the many hard hats and bandannas.I remember that march vividly, how we flooded the street. People climbed up lamp posts to take photos. Police, heavily armed military, were visible in all directions, on rooftops, at corners. The crowd had a carnival mood, loud, active, alive. We all shouted chants together, like marching music to clapping hands and drums and whistles. I remember two in particular I’d never heard before: “Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh! The N. L. F. is Gonna Win!!” and “Two! Four! Six! Eight! Organize and Smash the State!!”

What did these even mean? The N.L.F. – National Liberation Front – was the formal name for the Viet Cong, the group we were fighting at that moment in Vietnam. Was this treason against the country? In that moment, I didn’t seem to matter. The words were clever and striking and bold. I wouldn’t learn until much later that these two chants happened to be favorites of a radical group called the Weather Underground involved with bombings and arson. These were now my friends and comrades on that day, on that street, in that moment of good fun and shared adventure.

I also noticed, looking at the other marchers, how many of them, men and women alike, wore hard-hat helmets, the kind construction workers use. At the time, I thought it was probably just a style statement – solidarity with the working class? -- like the red bandannas and small canteens. Silly, naive me, not realizing that the hard hats were protection from police clubs and the bandannas, with a splash of water, from tear gas. These were not novices, my new friends. They came prepared.

On we marched, filling the street, chanting the chants, following the mock coffins, until we found ourselves on Pennsylvania Avenue directly in front of the White House. A few years later, in 1995 after the Oklahoma City bombing, the Secret Service would block off this section of Pennsylvania Avenue from local traffic, a security measure hardened and expanded after the attacks of September 11, 2001. But back in 1970, Pennsylvania Avenue was just another street, and that’s where we stood now.

Buses parked bumper-to-bumper to seal off the White House grounds from demonstrators.

Buses parked bumper-to-bumper to seal off the White House grounds from demonstrators.Having reached this point, the crowd grew restive. What next? The White House was blocked by the bumper-to-bumper buses. There was no way in. But the leaders up front had an answer: Let’s deliver the coffins by simply lifting them and heaving them over the buses. Cheers and whistles rose from the crowd as dozens of hands and arms joined in lifting the wooden boxes and as high as they could, but they couldn’t quite reach the tops of the buses.

What now? Again, no hesitation. The leaders up front, barely 10 feet away from where I stood with my little cadre of co-students and professor in the middle of the crowd, announced the answer. Let’s knock over the buses!! They can’t stop us!! Power to the People!! Right On!!

Tip the Buses!!And so the buses started shaking. Hundreds of hands and arms from the crowd now concentrated all their strength on rocking those buses, harder and harder, tilting them further and further. Realistically, could they actually have knocked one over? Or at least pushed it far enough to make an opening? And what if they did? What next? Were we ready to charge through? And what was waiting behind those buses? Soldiers? Police? National Guard?

A few years later, I would get a direct answer to that question. By the mid-1970s I was working as staff counsel to a US Senator and, one day at a Capitol Hill reception, I happened to meet one of the Marines assigned to the White House grounds that day. We started sharing stories. What he told me was this: “It’s a good thing you guys never managed to knock over that bus.” Stationed behind those buses, he explained, were not only Secret Service and DC police but also US Marines with live ammunition, instructed to protect the perimeter of the White House. Things could have gotten ugly very fast.

But we didn’t know that at the time. Maybe some suspected it, but nobody seemed to care, nobody seemed nervous. Instead, we were caught up in the moment, the cheers, the chants, the energy, the thousands of voices, the leaders urging us on.

It was at this precise moment that Professor Strauss managed to get our attention and pull our small group together into a tiny huddle like football players. I remember his words almost exactly. He said: “I know a really good Chinese restaurant over that way,” pointing in the direction away from the White House. “If we leave right now, we can get there before the rush.”

Chinese Food!!We followed his lead. Slowly, we threaded our way back through the crowd, away from the line of buses now shaking ever more violently. We had just reached the sidewalk and taken a few steps onto Lafayette Park when we heard commotion breaking out behind us, screams, people running. A volley of tear gas cannisters flew out from the White House grounds, over the busses and into the crowd. They exploded. Sparks and smoke rose sharply in the air. People ran, scattered, as the gas spread. We ran too, but we were in front of everyone else – still close enough to get a good whiff of the tear gas, but not enough to be trapped.

And yes, we eventually did make our way to that Chinese restaurant and got a table before the crowd.

Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about that day in Washington, D.C. I’ve tried to turn it into a funny story for the family, how I learned my lifelong appreciation for Asian food. The spot where our group was tear-gassed in May 1970 was barely a block away from where President Donald Trump in June 2020 would unleash tear gas to clear demonstrators from around Lafayette Park to make way for a photo op in front of Saint John’s Church, just across the street. This time, the demonstrators were protesting the shooting of George Floyd and calling for racial justice. Circumstances were different, but the parallels were hard to miss: the anger, the eagerness for confrontation, the resulting acrid smell of gas.

Donald Trump crossing Lafayette Park after police had cleared it with tear gas, June 1, 2020 - about a block from where I was gassed in May 1970.